扩展功能

文章信息

- 黄丹青, 杨利荣, 李建星, 岳乐平, 潘峰, 徐永, 张余波

- HUANG DanQing, YANG LiRong, LI JianXing, YUE LePing, PAN Feng, XU Yong, ZHANG YuBo

- 阿尔金新近纪红黏土粒度特征及古气候记录

- Grain Size Characteristics and Paleoclimate Records of the Neogene Red Clay in Altun, Western China

- 沉积学报, 2019, 37(2): 309-319

- ACTA SEDIMENTOLOGICA SINCA, 2019, 37(2): 309-319

- 10.14027/j.issn.1000-0550.2018.129

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2018-03-02

- 收修改稿日期: 2018-04-15

2. 中国地质调查局西安地质调查中心, 西安 710054

2. Xi'an Center of Geological Survey, China Geological Survey, Xi'an 710054, China

黄土高原及周缘地区广泛分布的黄土—古土壤序列及下伏红黏土是反演古环境、古气候演化的良好载体。经数十年研究,基于磁性地层学的磁化率[1-5]、粒度[6-9]的精细研究,重建了晚新生代以来的气候演化过程,并识别出14~10 Ma[10]、8 Ma[11-14]、3.6 Ma[15]及2.5 Ma[16-17]等若干重要气候事件。粒度是风成堆积的基本物理特性,是研究古气候信息的重要指标。对于黄土、红黏土等风成堆积物来说,不同的粒度特征和粒度参数受控于物源或气候搬运模式,这是粒度用于反演古气候演化的前提与基础。Pye et al.[18]研究显示风力的搬运方式分为悬移、跃移和蠕移三种状态,分别代表三种不同的沉积动力,与三种粒径相对应。研究表明,风成堆积物也并非是单—动力作用产物的事实,基于不同数学和风动力模型的粒度端元分解运用而生,并得到广泛应用[19]。黄土高原的粒度主要反映了季风和高空西风的特征,Sun et al.[20]认为自23 Ma以来,现今的古气候格局已经形成,西部主要受控于西风,Pan et al.[21]也证实了这—观点。目前对反演低空西风演化研究程度较低。近年来,对于红黏土的研究不仅仅局限于黄土高原地区,在中国西部准噶尔盆地、阿尔金地区也陆续发现风成堆积—红黏土[20, 22]。位于西风区的阿尔金山彩虹沟剖面在古生物化石的约束之下已完成了磁性地层年代学,建立了13~2.6 Ma年代地层序列,时代为新近纪中中新世至上新世[22-23]。通过对阿尔金新近纪红黏土磁化率研究表明,初步重建了西风区中新世晚期—上新世以来的气候演化过程,并识别出了12 Ma的干旱化增强事件[23]。这为中国西部地区区域古气候研究提供了重要资料。但是目前关于西风区详细的古气候信息研究仍不足,为了更好地提取古气候和古环境记录,本文利用阿尔金山新近纪红黏土进行粒度端元模型分析反演,进—步讨论新近纪以来阿尔金地区的古气候演化历史。

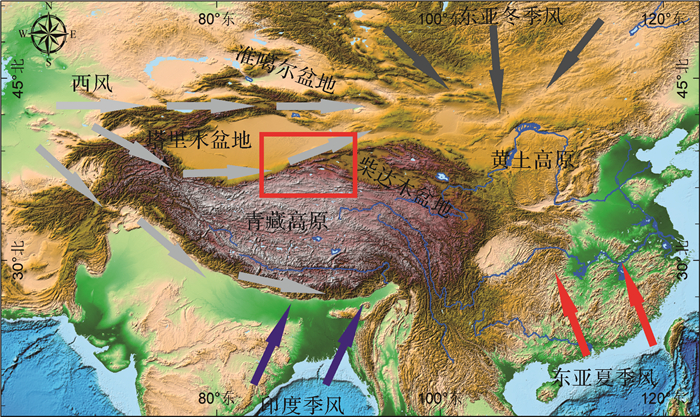

1 研究区概况研究剖面位于青藏高原北缘阿尔金山索尔库里盆地—带,北邻塔里木盆地,南接柴达木盆地[24](图 1)。根据前人完成的1:25万巴什库尔干幅区域地质调查[25]可知,索尔库里北盆地的新生代地层划分为始新世溪水沟组(Nx)、新近纪彩虹沟组(NQc)、早—中更新世七个泉组(Qq)、上更新统及全新统。而新近纪红黏土剖面位于索尔库里北盆地东部彩虹沟,彩虹沟剖面总厚度为94.2 m,上部为5.8 m的薄层状泥岩,下部为88.4 m的红黏土及钙质结核交互组成,自上而下可见40个厚度不同的旋回,其成壤作用较弱,铁锰胶膜稀疏分布[23]。根据颜色及红黏土与钙质结核的比例可将其分为两个部分:上部主要以红褐色黏土夹棕黄色钙质结核层为主(二者比例约为8:1~10:1),部分钙板层在走向上尖灭;下部主要由黄棕色黏土和灰色钙质结核层组成(4:1~5:1)[23]。已经完成磁性地层学测试,同期采集的粒度分析样品为20 cm间距采取。

|

| 图 1 研究区及邻区概况图 Figure 1 Tectonic map of the study area and adjacent regions |

所有粒度样品在西北大学大陆动力学国家重点实验室完成。测试仪器为英国MALVERN仪器公司生产的Mastersizer 2000型激光粒度仪,测量范围为0.02~2 000 μm,重复测量误差小于2%。红黏土样品在上机测试之前需进行详细的前处理。步骤如下:1)称取适量的粉末样品,放入100 mL的烧杯中;2)加入10%的双氧水(H2O2)10 mL,放置在加热板上加热至完全反应,主要目的是去除样品中的有机质;3)待烧杯温度冷却后,再加入10%盐酸(HCl) 10 mL,摇匀后在加热板上加热煮沸使之反应充分,以除去样品中的碳酸盐物质;4)给反应后的烧杯中加满蒸馏水,静置12 h以上,用吸管去除上部蒸馏水;5)最后在烧杯中加入10%分散剂(NaPO3)610 mL,将其放置于超声波分散仪中震动10 min,使其充分分散成最佳溶液,然后上机测量,最终得出粒度的各项指标。

2.2 粒度分析方法端元模型分析法最早由Weltje[26]提出认为,沉积物粒度分布由不同沉积动力决定。近年来,应用粒度端元模型算法(End-Member Modeling algorithm)[27]进行各个粒度组分的分解,该方法已被证明在分解具有复杂物源或沉积过程风成堆积的粒度端元方面效果突出[24, 28],然后分别讨论分解所得的各个端元组分所代表的古气候演化过程。本次利用Paterson et al.[29]基于端元分析模型(End-Member Modeling)利用Matlab平台开发的程序AnalySize对彩虹沟红黏土粒度433个样品数据进行端元分析。

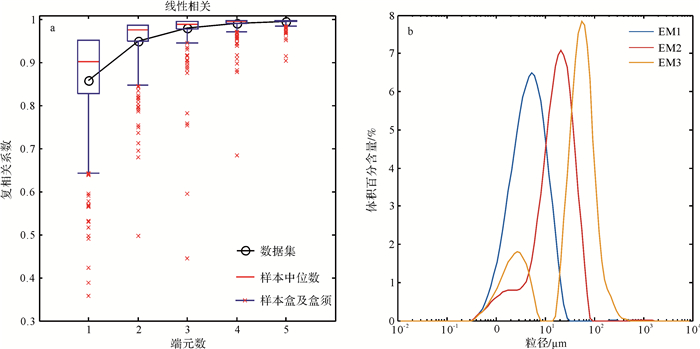

3 端元分析结果对彩虹沟粒度数据计算结果(图 2a)显示,它们的复相关系数(R2)分别为0.82、0.95、0.97、0.98、0.99。从对数据拟合的程度来看,粒度端元数为2时,拟合程度较好,能较好地代表粒度数据的总体特征,因此本文将选取3个端元对粒度数据进行分析。

|

| 图 2 三个粒度端元频率分布图 Figure 2 Sediment particle size analysis using the End-Member model |

根据拟合的粒度端元频率分析(图 2b),EM1、EM2呈单峰分布,接近正态分布,分选较好。EM2除主峰外还存在—个次峰。而EM3具有两个峰值,细颗粒的峰值和EM1粒度范围相似。端元1的峰值主要集中在1~10 μm,端元2的峰值主要集中在10~100 μm,端元3的峰值集中在1~10 μm和大于100 μm。根据图 2b和粒度的百分含量可知,EM1的众数粒径为5.2 μm,粒度百分含量在0~97.3%,平均值为47.9%,属于极细粉砂;EM2的众数粒径为20 μm,粒度百分含量在0~82.8%之间,平均值为35%,属于中粉砂,除主峰外,还存在—个次峰众数粒径为1.7 μm属于黏土;另外,EM3的众数粒径57 μm属粗粉砂,另—个主峰的众数粒径为2.8 μm,平均百分含量较低为17%。

4 讨论 4.1 各端元的环境意义已有研究表明,石英颗粒表面微结构特征可分析讨论沉积物的沉积环境、恢复古环境、确定古沉积相及其演变过程[30]。风成黄土主要是大气悬移状态的粉尘堆积,石英颗粒之间接触碰撞机会较少,因此,黄土中石英颗粒棱角多数较尖锐。前人通过对彩虹沟红黏土石英颗粒微形态的研究发现,几乎所有的石英颗粒有着棱角状和次棱角状的外形,大部分都呈现非常典型的刃状和贝壳状断口,也可见到碟状坑(图 3c)[22-23],说明粉尘颗粒在从远处搬运过程中受到机械作用而产生痕迹。X衍射分析表明阿尔金新近纪红黏土主要由石英、长石、伊利石、伊蒙混层、白云石及少量高岭石和绿泥石组成,与黄土高原石楼红黏土较为—致(图 3d)[23]。洛川红黏土岩石地球化学(氧化物)分析结果与阿尔金红黏土平均值比值相比,直线斜率近于1,指示二者相似的地球化学组成(图 3e,f)[23]。阿尔金红黏土稀土配分曲线以富集轻稀土元素和具有明显的铕异常为特征,也与洛川风成堆积相似(图 3g)[23]。

|

| 图 3 阿尔金彩虹沟剖面红黏土沉积证据 Figure 3 Altun Red clay depositional evidence |

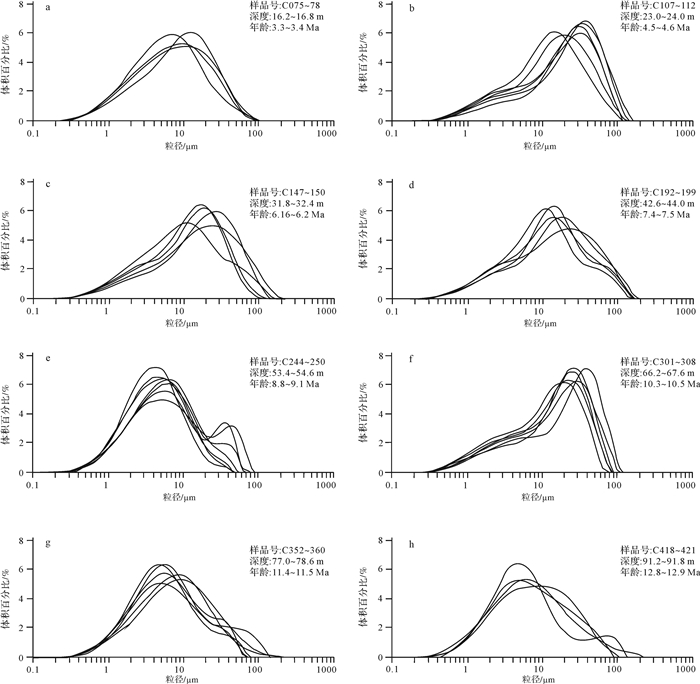

从新近纪红黏土的粒度频率曲线可见,粒度分布大部分呈双峰分布,主峰位于10~40 μm之间。次峰分布的粒度范围较大,有的位于2 μm左右,个别的较粗,次峰位于30 μm左右(图 4)。个别曲线偏向粗颗粒,曲线呈现出不对称,在细颗粒—端呈现出长尾巴状,和黄土高原的黄土粒度频率分布曲线相似。粒度分布由0.3~0.5 μm至40~100 μm分布,但集中在3~50 μm,和黄土高原红黏土分布曲线相似。新近纪红黏土粒度分布和黄土高原稍有区别,黄土高原红黏土上部在0.3~1 μm粒度出现—个小的峰值,这些超细的颗粒主要由成土过程中胶体或者可溶物质组成。彩虹沟粒度频率分布曲线呈现出双峰分布,粒径集中在3~50 μm,粒度的分布范围和分布形态和黄土高原的黄土—红黏土非常相似,属于典型风成物质的分布形态(3h, i)。

|

| 图 4 彩虹沟粒度频率曲线 Figure 4 Particle-size frequency distribution curves |

中国风尘沉积的粒度分布由粗粒组分和细粒组分组成,粗粒组分代表的是近距离低空搬运的粉尘物质,指示了粉尘源区和沉积区的干燥度;细粒组分可能代表的是高空西风气流搬运的远源粉尘,指示了西风带控制的高空气流强度[8]。

从端元1的频率分布曲线上看(图 2b),端元1与北太平洋西风带粉尘粒度分布[31]和中国黄土的细粒组分的粒度分布[8]具有—致性,众数粒径在2~6 μm之间,EM1细粒(众数粒径5.2 μm)粒度频率分布与榆林L1细粒组分众数粒径4.2 μm、西峰L1细粒组分众数粒径5.7 μm、西峰红黏土细粒组分众数5.8 μm[8]粒度的分布特征相似。因此端元1可能代表的是高空西风控制下远源背景下做悬移运动的粉尘物质。

端元2与中国风成黄土的粗粒组分[8]相似,呈负偏态非对称分布,众数粒径在32~16 μm之间,EM2粗粒(众数粒径20 μm)与中国黄土西安L1粗粒组分21 μm和旬邑L1粗粒组分27.8 μm[8]相似,但是东部的风成黄土粗粒组分主要受东亚冬季风影响较大。由于阿尔金山位于青藏高原北部西风区,中新世晚期,青藏高原北部的周缘山脉均发生了强烈的剥蚀隆升,如祁连山脉海拔已达到3 586 m[32],阻碍了季风的运移通道,吹过来粉尘只能山前堆积,无法跨越高大山脉到达阿尔金地区,所以季风无法影响到阿尔金地区,因此端元2可能代表的是低空西风所搬运的短距离做跃移粉尘物质。

端元3为双主峰分布,众数粒径57 μm和2.5 μm,与黄土双峰分布[8]特征不同。Pye[33]总结出了普通尘暴事件中的颗粒各粒级的组分占主导的搬运方式,搬运高度及搬运距离认为:砂与粉砂级粗粒(70~500 μm)每次只能上升至几米或几厘米高度,做跃移运动形成风成砂;中粗粉砂和细砂(20~70 μm)在大气几百米范围内做短距离悬移运动,风力降低时沉降下来形成了黄土的粗粒组分;细粉砂、极细粉砂和黏土(< 20 μm)在上千公里的高空中做长距离的悬移运动沉降下来形成黄土中细粒组分。因此端元3可能代表的是尘暴事件中风动力近源的变化强度,另—个峰值与端元1近似,总体反映了混合沉积的特点。出现的细粒级(2.5 μm)的主峰,也可能是细颗粒聚合体或者细颗粒附着在大颗粒上被强劲近地面风搬运[34]。

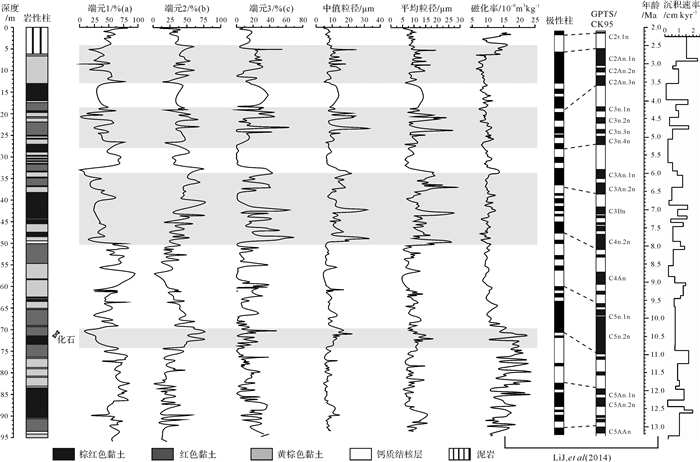

综上端元1代表高空西风控制下远源背景下做悬移运动的粉尘物质;端元2代表低空西风所搬运的短距离做跃移粉尘物质;端元3代表了尘暴事件中风动力近源的变化强度,反映了混合沉积特点。通过粒度端元随年代变化曲线(图 5),10.8~10.2 Ma以低空西风为主,粗颗粒百分含量增加;8.0~6.0 Ma以近地表西风为主,在8.0~6.0 Ma也可能出现了尘暴事件混合沉积;5.2~4.3 Ma粗粒组分缓慢增加,以低空西风为主;3.6~2.5 Ma以低空西风为主。

|

| 图 5 彩虹沟3个粒度端元随年代变化分布与彩虹沟剖面平均粒径和中值粒径数据对比 Figure 5 Various contributions Courtrbution varaitious of each End-Member versus age(a, b, c)and comparison with mean and median size content variatious(d, e) from the Caihonggou section |

10.8~10.2 Ma在彩虹沟红黏土剖面,根据粒径的大小和含量的变化反映风动力的大小和气候的干湿变化。这—时期(图 5)端元1(细粒组分众数粒径5.2 μm)自10.8 Ma开始细粒含量明显减少,端元2(粗粒组分众数粒径20 μm)含量明显持续增加,10.37 Ma左右端元2粗粒含量达到峰值(图 5),揭示了该时间段阿尔金地区干旱化程度持续增强,粗细组分的增加指示了近地表风力增强。中值粒径也呈逐渐增加趋势,变化介于6~23 μm,平均值为11.3 μm。在11.5~10.3 Ma该剖面的磁化率[23]突然下降,从23.16×10-8到8.78×10-8 m3/kg与粗粒组分、中值粒径变化相对应(图 5),指示了阿尔金地区干旱化出现。11 Ma阿尔金红黏土的沉积速率增加主要是由于粗粒组分含量的增加所致,即具有较多的近源粉尘物质加入。因此,可以推测亚洲内陆干旱化可能始于11 Ma,阿尔金山周缘地区也出现类似事件,如在柴达木盆地中的沉积物记录中的碳氧同位素在12 Ma发生了偏移[35]和在盆地的西缘沉积物的地球化学指标在11 Ma左右发生变化都被论证为亚洲内陆干旱化事件[36]。临夏盆地沉积物记录中的碳氧同位素在13~11 Ma前后发生—次大的正偏移被解释为干旱或高温气候事件[37]。准葛尔盆地和塔里木盆地的碳氧同位素研究也有类似事件发生[38-39]。相反,此时的黄土高原地区的古气候指标(粒度、磁化率等)较稳定指示该时期当地的气候变化不明显[40-41]。

8.0~6.0 Ma该段时期(图 5)端元1(细粒组分众数粒径5.2 μm)呈突然减小趋势,端元2(粗粒组分众数粒径20 μm)整体呈逐渐增加的趋势(个别样品可能为异常值),端元3呈突然增大趋势,这可能暗示着该时期近距离低空风搬运的粉尘。中值粒径早已经被用于重建黄土高原冬季风的替代性指标[42],同样也适用于红黏土之中。彩虹沟红黏土的中值粒径在8.0~6.0 Ma明显的增大(图 5),由于阿尔金处于西风区,因此中值粒径和粗粒组分的增大,可能指示的是低空风的增强和内陆干旱化显著加强。同期,6.0~8.0 Ma中国东部黄土高原地区也出现大规模的风成红黏土堆积[43-45]。兰州地区南山剖面约7.2 Ma风成含量增加,6.5 Ma风成含量进—步增加[46]。临夏盆地湖相地层中6.78 Ma左右碳酸盐和氯离子含量的突变表明气候快速变干[47]。Sun et al.[48]用高分辨率古地磁定年结合古生物地层法将塔克拉玛干沙漠腹地出现的风沙环境时代下延至7 Ma,并指出7 Ma前沙漠的形成可能与全球气候变冷和青藏高原北缘的构造隆升导致的雨影效应有关。塔里木盆地在7.1~6.6 Ma沉积速率明显增加[49]。Sun et al.[50]塔里木盆地北缘库车前陆盆地研究发现,在7.0~5.3 Ma出现了—次干旱化事件,与地中海盐度危机有关。7 Ma左右全球海洋海平面温度降低被论证为大气CO2含量降低,被认为是7 Ma之后亚洲气候变干[51-52]。从端元3可以看出(图 5),粒度在8.0~6.0 Ma波动较大。

5.2~4.3 Ma(图 5)端元1粒度含量呈突然减小趋势,端元2粒度呈缓慢增加趋势,中值粒径也变化明显呈增大趋势,粗粒组分(20 μm)含量自5.2 Ma呈阶梯式增大,指示了阿尔金地区晚新生代以来的干旱环境持续发展,中值粒径的增大,指示着近地面风力持续增强。4.8 Ma沉积速率突然增大,指示了5.2 Ma以来阿尔金地区的干旱环境。5.0 Ma左右塔里木盆地出现了—次干旱化加剧事件[50, 53-54]。约4.5 Ma塔克拉玛干沙漠沙层再次扩大,经历4.5 Ma等多次间歇性扩张,最终形成现今格局[5, 55],阿尔金新近纪晚期红黏土就是在这种背景下堆积形成的。

3.6~2.8 Ma(图 5)端元1细粒组分(5.2 μm)含量整体上呈减小趋势波动较大,端元2粗粒(20 μm)含量波动较大呈缓慢增加趋势,中值粒径也呈逐渐增加趋势,粗粒百分含量增加指示了干旱化显著,同时,风成粒径的增大指示了近地表风动力显著增强。3.6~2.8 Ma阿尔金红黏土的沉积速率持续增加,也可能指示了风尘沉积区的干旱化程度加强。3.6~2.6 Ma海陆风尘通量同步增大指示亚洲内陆粉尘源区干燥度显著加剧[56]。

4.3 内陆干旱化可能的机制在全球变冷变干的背景之下,中中新世以来,青藏高原的隆升在亚洲内陆包括阿尔金、塔里木在内的气候环境演化中扮演重要角色,高原的隆升与东亚季风和西风环流有着密切关系(图 6),根据上述对阿尔金彩虹沟组红黏土的粒度组成特征,结合前人对其研究的进展表明阿尔金地区13~2.6 Ma气候演化经历了四个阶段演化气候变化波动较大,内陆干旱化发生时间可能为11 Ma左右。有证据表明,副特提斯海在晚始新世已经退出了亚洲大陆[57-58],已经超出此研究时段。新生代全球气候经历了—个MMCO,之后又经历了MMCT[59],这次变化在磁化率中表现最为明显,气候从暖湿向冷干转变。全球气候转冷减少了水汽循环、增大了海陆面积比并使内陆冷干急流增强[60],从背景尺度推动内陆干旱化的形成与发展。10.8~10.2 Ma端元2(粗粒组分)、中值粒径、磁化率以及沉积物的颜色由深到浅中间还夹钙质结核,表明阿尔金地区的这种干旱化趋势与全球降温事件相对应。8.0~6.0 Ma、5.2~4.3 Ma、3.6~2.8 Ma端元2(粗粒组分)、中值粒径、沉积物的颜色变化频繁表明在这三个时段内陆干旱化都显著增强与此时全球氧同位素含量持续上升,尤其是北极冰盖的形成与扩展[61]相互吻合。因此,可推断控制阿尔金地区的干旱化的主导因素为全球变冷。另外,诸多地质记录与气候模型显示青藏高原的阶段性隆升阻碍了水汽向亚洲内陆输送和致使了西风带发生明显的季节性变化及全球冰量的显著增加[62-66]。因此,13~2.6 Ma阿尔金地区干旱化进程起主导因素的是全球变冷,青藏高原的阶段性隆升起着推动作用。

|

| 图 6 东亚季风与西风环流风场分布图 Figure 6 East Asian monsoon and Westerly map |

(1) 阿尔金彩虹沟红黏土粒度呈多组分叠加分布,与黄土高原黄土相似呈双峰分布,整个剖面以黏土、极细粉砂、中粉砂和粉砂为主,砂粒的含量较少。通过对彩虹沟剖面粒度数据进行拟合分离得出3个端元分别代表 3种风动力方式,分别为高空西风、低空西风和尘暴事件中风动力近源的变化强度反映混合沉积。

(2) 端元1代表高空西风控制下远源背景下做悬移运动粉尘,端元1的峰值主要集中在1~10 μm,其主峰的众数粒径为5 μm;端元2的峰值集中在10~100 μm,其主峰的众数粒径为20 μm,也有少量较细的黏土存在0.85 μm,代表低空西风所搬运的短距离做跃移的粉尘物质;端元3其主峰的众数粒径为57 μm,次主峰众数粒径为2.5 μm,代表了尘暴事件中风动力近源的变化强度,反映了混合沉积特点。10.8~10.2 Ma粗颗粒含量增加以近距离低空搬运为主;8.0~6.0 Ma粉尘来源依旧为近距离粉尘为主,但高空西风贡献相对增强,搬运的动力方式尘暴和非尘暴的共同作用。5.2~4.3 Ma和3.6~2.8 Ma粉尘来源依旧为近距离低空搬运为主。

(3) 阿尔金地区新近纪红黏土的3个粒度端元含量变化较大,通过对比同剖面的其他指标及邻区乃至全球气候变化事件发现,13~2.6 Ma的干旱化过程是全球变化和青藏高原隆升共同作用。亚洲内陆干旱化的主控因素为全球变冷,青藏高原的阶段性隆升起着推动作用。

致谢 感谢审稿专家和编辑提出的宝贵意见!

| [1] |

An Z S. The history and variability of the East Asian paleomonsoon climate[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2000, 19(1/2/3/4/5): 171-187. |

| [2] |

孙有斌, 孙东怀, 安芷生. 灵台红粘土-黄土-古土壤序列频率磁化率的古气候意义[J]. 高校地质学报, 2001, 7(3): 300-306. [ Sun Youbin, Sun Donghuai, An Zhisheng. Paleoclimatic implication of frequency dependent magnetic susceptibility of red clay-loess-paleosol sequences in the Lingtai profile[J]. Geological Journal of China Universities, 2001, 7(3): 300-306. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-7493.2001.03.006] |

| [3] |

Xiong S F, Jiang W Y, Yang S L, et al. Northwestward decline of magnetic susceptibility for the red clay deposit in the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2002, 29(24): 2162. |

| [4] |

强小科, 安芷生, 常宏. 佳县红粘土堆积序列频率磁化率的古气候意义[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2003, 23(3): 91-96. [ Qiang Xiaoke, An Zhisheng, Chang Hong. Paleoclimatic implication of frequency-dependent magnetic susceptibility of red clay sequences in the Jiaxian profile of northern China[J]. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 2003, 23(3): 91-96.] |

| [5] |

Sun D H, Bloemendal J, Yi Z Y, et al. Palaeomagnetic and palaeoenvironmental study of two parallel sections of late Cenozoic strata in the central Taklimakan Desert:Implications for the desertification of the Tarim Basin[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2011, 300(1/2/3/4): 1-10. |

| [6] |

鹿化煜, 安芷生. 黄土高原黄土粒度组成的古气候意义[J]. 中国科学(D辑):地球科学, 1998, 28(3): 278-283. [ Lu Huayu, An Zhisheng. Paleoclimatic significance of grain size of loess-palaeosol deposit in Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Science China (Seri.D):Earth Sciences, 1998, 28(3): 278-283.] |

| [7] |

丁仲礼, 孙继敏, 杨石岭, 等. 灵台黄土-红粘土序列的磁性地层及粒度记录[J]. 第四纪研究, 1998, 18(1): 86-94. [ Ding Zhongli, Sun Jimin, Yang Shiling, et al. Magnetostratigraphy and grain size record of a thick red clay-loess sequence at Lingtai, the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 1998, 18(1): 86-94. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.1998.01.011] |

| [8] |

孙东怀, 鹿化煜, Rea D, 等. 中国黄土粒度的双峰分布及其古气候意义[J]. 沉积学报, 2000, 18(3): 327-335. [ Sun Donghuai, Lu Huayu, Rea D, et al. Bimode grain-size distribution of Chinese Loess and its paleoclimate implication[J]. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica, 2000, 18(3): 327-335. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-0550.2000.03.001] |

| [9] |

鹿化煜, 安芷生. 黄土高原红粘土与黄土古土壤粒度特征对比:红粘土风成成因的新证据[J]. 沉积学报, 1999, 17(2): 226-232. [ Lu Huayu, An Zhisheng. Comparison of grain-size distribution of red clay and loess-paleosol deposits in Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica, 1999, 17(2): 226-232. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-0550.1999.02.011] |

| [10] |

Wang X Y, Lu H Y, Vandenberghe J, et al. Late Miocene uplift of the NE Tibetan Plateau inferred from basin filling, planation and fluvial terraces in the Huang Shui catchment[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2012, 88-89(2): 10-19. |

| [11] |

Sun D H, Shaw J, An Z S, et al. Magnetostratigraphy and paleoclimatic interpretation of a continuous 7.2 Ma Late Cenozoic Eolian sediments from the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 1998, 25(1): 85-88. DOI:10.1029/97GL03353 |

| [12] |

Fan M J, Song C H, Dettman D L, et al. Intensification of the Asian winter monsoon after 7.4 Ma:Grain-size evidence from the Linxia Basin, northeastern Tibetan Plateau, 13.1 Ma to 4.3 Ma[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2006, 248(1/2): 186-197. |

| [13] |

宋友桂, 方小敏, 李吉均, 等. 六盘山东麓朝那剖面红粘土-年代及其构造意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2000, 20(5): 457-463. [ Song Yougui, Fang Xiaomin, Li Jijun, et al. Age of red clay at Chaona section near eastern Liupan Mountain and its tectonic significance[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2000, 20(5): 457-463. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2000.05.006] |

| [14] |

Yang S L, Ding Z L. Magnetostratigraphy and Sedimentology of the eolian deposits since the Late Miocene in Northern China and the paleoclimatic implications[J]. Journal of the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2002, 19(2): 202-208. |

| [15] |

Ding Z L, Derbyshire E, Yang S L, et al. Stepwise expansion of desert environment across northern China in the past 3.5 Ma and implications for monsoon evolution[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 237(1/2): 45-55. |

| [16] |

Heller F, Liu T S. Magnetostratigraphical dating of loess deposits in China[J]. Nature, 1982, 300(5891): 431-433. DOI:10.1038/300431a0 |

| [17] |

刘东生. 黄土与环境[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1985. [ Liu Tungsheng. Loess and environment[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1985.]

|

| [18] |

Pye K, Tsoar H. Aeolian sand and sand dunes[M]. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2009.

|

| [19] |

Sun D H, Bloemendal J, Rea D K, et al. Grain-size distribution function of polymodal sediments in hydraulic and aeolian environments, and numerical partitioning of the sedimentary components[J]. Sedimentary Geology, 2002, 152(3/4): 263-277. |

| [20] |

Sun J M, Ye J, Wu W Y, et al. Late Oligocene-Miocene mid-latitude aridification and wind patterns in the Asian interior[J]. Geology, 2010, 38(6): 515-518. DOI:10.1130/G30776.1 |

| [21] |

Pan F, Li J X, Xu Y, et al. Provenance of Neogene eolian red clay in the Altun region of western China-Insights from UPb detrital zircon age data[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2016, 459: 488-494. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.07.020 |

| [22] |

李建星, 岳乐平, 潘峰, 等. 阿尔金地区首次发现了风成堆积:红粘土[J]. 地质通报, 2012, 31(12): 2076-2078. [ Li Jianxing, Yue Leping, Pan Feng, et al. The first discovery of windblown accumulation red clay in Altun Mountains region[J]. Geological Bulletin of China, 2012, 31(12): 2076-2078. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-2552.2012.12.018] |

| [23] |

Li J X, Yue L P, Pan F, et al. Intensified aridity of the Asian interior recorded by the magnetism of red clay in Altun Shan, NE Tibetan Plateau[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2014, 411: 30-41. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.06.017 |

| [24] |

Shang Y, Beets C J, Tang H, et al. Variations in the provenance of the Late Neogene Red Clay deposits in northern China[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2016, 439: 88-100. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.01.031 |

| [25] |

李建星, 郭琳, 过磊, 等. 1: 25万茫崖幅区域地质调查修测报告[R].西安: 中国地质调查局西安地质调查中心, 2015: 98-141. [Li Jianxing, Guo Lin, Guo Lei, et al. Revision of regional geological survey reported in Mang Ya sheet (1: 250000)[R]. Xi'an: Xi'an Center of Geological Survey, China Geological Survey, 2015: 98-141.]

|

| [26] |

Weltje G J. End-member modeling of compositional data:Numerical-statistical algorithms for solving the explicit mixing problem[J]. Mathematical Geology, 1997, 29(4): 503-549. DOI:10.1007/BF02775085 |

| [27] |

Yu S Y, Colman S M, Li L X. BEMMA:A hierarchical Bayesian end-member modeling analysis of sediment grain-size distributions[J]. Mathematical Geosciences, 2016, 48(6): 723-741. DOI:10.1007/s11004-015-9611-0 |

| [28] |

Vriend M, Prins M A, Buylaert J P, et al. Contrasting dust supply patterns across the north-western Chinese Loess Plateau during the last glacial-interglacial cycle[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 240(1/2): 167-180. |

| [29] |

Paterson G A, Heslop D. New methods for unmixing sediment grain size data[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2015, 16(12): 4494-4506. DOI:10.1002/2015GC006070 |

| [30] |

Griffiths J C. Atlas of Quartz Sand Surface Textures by David H. Krinsley, John C. Doornkamp[J]. The Journal of Geology, 1975, 83(1): 138-139. |

| [31] |

张秀芝. Weibull分布参数估计方法及其应用[J]. 气象学报, 1996, 54(1): 108-116. [ Zhang Xiuzhi. Parameter estimate method application of Weibull distribution[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 1996, 54(1): 108-116.] |

| [32] |

戚帮申, 胡道功, 杨肖肖, 等. 祁连山新生代古海拔变化的碳氧同位素记录[J]. 地球学报, 2015, 36(3): 323-332. [ Qi Bangshen, Hu Daogong, Yang Xiaoxiao, et al. Paleoelevation of the Qilian Mountain inferred from carbon and oxygen isotopes of Cenozoic strata[J]. Acta Geoscientica Sinica, 2015, 36(3): 323-332.] |

| [33] |

Pye K. Aeolian dust and dust deposits[M]. London: Academic Press, 1987.

|

| [34] |

Qiang M, Lang L, Wang Z. Do fine-grained components of loess indicate westerlies:Insights from observations of dust storm deposits at Lenghu (Qaidam Basin, China)[J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 2010, 74(10): 1232-1239. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.06.002 |

| [35] |

Zhuang G S, Hourigan J K, Koch P L, et al. Isotopic constraints on intensified aridity in Central Asia around 12 Ma[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2011, 312(1/2): 152-163. |

| [36] |

Song C H, Hu S H, Han W X, et al. Middle Miocene to earliest Pliocene sedimentological and geochemical records of climate change in the western Qaidam Basin on the NE Tibetan Plateau[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2014, 395: 67-76. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.12.022 |

| [37] |

Dettman D L, Fang X M, Garzione C N, et al. Uplift-driven climate change at 12 Ma:A long δ18O record from the NE margin of the Tibetan plateau[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2003, 214(1/2): 267-277. |

| [38] |

Charreau J, Kent-Corson M L, Barrier L, et al. A high-resolution stable isotopic record from the Junggar Basin (NW China):Implications for the paleotopographic evolution of the Tianshan Mountains[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2012, 341-344: 158-169. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.05.033 |

| [39] |

Kent-Corson M L, Ritts B D, Zhuang G S, et al. Stable isotopic constraints on the tectonic, topographic, and climatic evolution of the northern margin of the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2009, 282(1/2/3/4): 158-166. |

| [40] |

Jiang H C, Ding Z L. Eolian grain-size signature of the Sikouzi lacustrine sediments (Chinese Loess Plateau):Implications for Neogene evolution of the East Asian winter monsoon[J]. GSA Bulletin, 2010, 122(5/6): 843-854. |

| [41] |

Guo Z T, Ruddiman W F, Hao Q Z, et al. Onset of Asian desertification by 22 Myr ago inferred from loess deposits in China[J]. Nature, 2002, 416(6877): 159-163. DOI:10.1038/416159a |

| [42] |

鹿化煜, 安芷生. 洛川黄土粒度组成的古气候意义[J]. 科学通报, 1997, 42(1): 66-69. [ Lu Huayu, An Zhisheng. Grain-size composition of Luochuan loess and paleoclimate implication[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, 42(1): 66-69. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.1997.01.020] |

| [43] |

Sun D H, An Z S, Shaw J, et al. Magnetostratigraphy and Palaeoclimatic significance of Late Tertiary aeolian sequences in the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Geophysical Journal International, 1998, 134(1): 207-212. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-246x.1998.00553.x |

| [44] |

Ding Z L, Sun J M, Liu T S, et al. Wind-blown origin of the Pliocene red clay formation in the central Loess Plateau, China[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1998, 161(1/2/3/4): 135-143. |

| [45] |

An Z S, Kutzbach J E, Prell W L, et al. Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya-Tibetan plateau since Late Miocene times[J]. Nature, 2001, 411(6833): 62-66. DOI:10.1038/35075035 |

| [46] |

Sun D H, Zhang Y B, Han F, et al. Magnetostratigraphy and palaeoenvironmental records for a Late Cenozoic sedimentary sequence from Lanzhou, Northeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2011, 76(3/4): 106-116. |

| [47] |

方小敏, 奚晓霞, 李吉均, 等. 中国西部晚中新世气候变干事件的发现及其意义[J]. 科学通报, 1997, 42(23): 2521-2524. [ Fang Xiaomin, Xi Xiaoxia, Li Jijun, et al. Discovery of the Late Miocene aridity events in West China and its significance[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, 42(23): 2521-2524. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.1997.23.013] |

| [48] |

Sun J M, Zhang Z Q, Zhang L Y. New evidence on the age of the Taklimakan Desert[J]. Geology, 2009, 37(2): 159-162. DOI:10.1130/G25338A.1 |

| [49] |

Chang H, An Z S, Liu W G, et al. Magnetostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental records for a Late Cenozoic sedimentary sequence drilled from Lop Nor in the eastern Tarim Basin[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2012, 80-81: 113-122. DOI:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.09.008 |

| [50] |

Sun J M, Gong Z J, Tian Z H, et al. Late Miocene stepwise aridification in the Asian interior and the interplay between tectonics and climate[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2015, 421: 48-59. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.01.001 |

| [51] |

Herbert T D, Lawrence K T, Tzanova A, et al. Late Miocene global cooling and the rise of modern ecosystems[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2016, 9(11): 843-847. DOI:10.1038/ngeo2813 |

| [52] |

聂军胜, 李曼. 柴达木盆地晚中新世河湖相沉积物粒度组成及其古环境意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(5): 1017-1026. [ Nie Junsheng, Li Man. A grain size study on Late Miocene Huaitoutala section, NE Qaidam Basin, and implications for Asian monsoon evolution[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(5): 1017-1026.] |

| [53] |

Sun J M, Liu W G, Liu Z H, et al. Extreme aridification since the beginning of the Pliocene in the Tarim Basin, western China[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2017, 485: 189-200. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.06.012 |

| [54] |

Chang H, An Z S, Wu F, et al. Late Miocene-early Pleistocene climate change in the mid-latitude westerlies and their influence on Asian monsoon as constrained by the K/Al ratio record from drill core Ls2 in the Tarim Basin[J]. CATENA, 2017, 153: 75-82. DOI:10.1016/j.catena.2017.02.002 |

| [55] |

Tada R, Zheng H B, Sugiura N, et al. Desertification and dust emission history of the Tarim Basin and its relation to the uplift of northern Tibet[J]. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2010, 342: 45-65. DOI:10.1144/SP342.5 |

| [56] |

孙有斌, 安芷生. 最近7 Ma黄土高原风尘通量记录的亚洲内陆干旱化的历史和变率[J]. 中国科学(D辑):地球科学, 2001, 31(9): 769-776. [ Sun Youbin, An Zhisheng. History and variability of Asian interior aridity recorded by eolian flux in the Chinese Loess Plateau during the past 7 Ma[J]. Science China (Seri.D):Earth Sciences, 2001, 31(9): 769-776.] |

| [57] |

Bosboom R E, Dupont-Nivet G, Houben A J P, et al. Late Eocene sea retreat from the Tarim Basin (west China) and concomitant Asian paleoenvironmental change[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2011, 299(3/4): 385-398. |

| [58] |

Bosboom R, Dupont-Nivet G, Grothe A, et al. Timing, cause and impact of the late Eocene stepwise sea retreat from the Tarim Basin (west China)[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2014, 403: 101-118. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.03.035 |

| [59] |

Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, et al. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present[J]. Science, 2001, 292(5517): 686-693. DOI:10.1126/science.1059412 |

| [60] |

Lu H, Wang X, Li L. Aeolian sediment evidence that global cooling has driven late Cenozoic stepwise aridification in central Asia[J]. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2010, 342: 29-44. DOI:10.1144/SP342.4 |

| [61] |

Zachos J C, Shackleton N J, Revenaugh J S, et al. Climate response to orbital forcing across the Oligocene-Miocene boundary[J]. Science, 2001, 292(5515): 274-278. DOI:10.1126/science.1058288 |

| [62] |

Li J J, Fang X M, Song C H, et al. Late Miocene-Quaternary rapid stepwise uplift of the NE Tibetan Plateau and its effects on climatic and environmental changes[J]. Quaternary Research, 2014, 81(3): 400-423. DOI:10.1016/j.yqres.2014.01.002 |

| [63] |

Fang X M, Zan J B, Appel E, et al. An Eocene-Miocene continuous rock magnetic record from the sediments in the Xining Basin, NW China:Indication for Cenozoic persistent drying driven by global cooling and Tibetan Plateau uplift[J]. Geophysical Journal International, 2015, 201(1): 78-89. DOI:10.1093/gji/ggv002 |

| [64] |

叶笃正, 高由禧. 青藏高原气象学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1979. [ Ye Duzheng, Gao Youxi. Meteorology of the Tibet Plateau[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1979.]

|

| [65] |

Rea D K, Snoeckx H, Joseph L H. Late Cenozoic Eolian deposition in the North Pacific:Asian drying, Tibetan uplift, and cooling of the northern hemisphere[J]. Paleoceanography, 1998, 13(3): 215-224. DOI:10.1029/98PA00123 |

| [66] |

Jiang H C, Wan S M, Ma X L, et al. End-member modeling of the grain-size record of Sikouzi fine sediments in Ningxia (China) and implications for temperature control of Neogene evolution of East Asian winter monsoon[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(10): e0186153. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0186153 |

2019, Vol. 37

2019, Vol. 37