扩展功能

文章信息

- 刘芮岑, 李祥辉, 胡修棉

- LIU RuiCen, LI XiangHui, HU XiuMian

- 湖南茶陵盆地晚白垩世古降水氧同位素

- Late Cretaceous Oxygen Isotope of Paleoprecipitation in Chaling Basin, Hunan Province

- 沉积学报, 2018, 36(6): 1169-1176

- ACTA SEDIMENTOLOGICA SINCA, 2018, 36(6): 1169-1176

- 10.14027/j.issn.1000-0550.2018.107

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-11-30

- 收修改稿日期: 2018-03-12

近几十年来氧同位素温度指针对古气候的定量研究起到了关键作用。然而,利用该指针对水文循环及其与气候系统相互作用的研究甚少[1]。近期对成壤碳酸盐、成壤菱铁矿、化石牙齿磷酸盐等氧同位素研究已有了古水文方面的典型研究实例[2-8],而通过成壤碳酸盐δ18O数据来探讨北美白垩纪阿普第期—阿尔布期的水文循环,推算大气水δ18Ow组成[5-9],则是新近古水文与古气候相结合的代表性成果,为古降水的氧同位素研究提供了先例,也为进行古水文研究开启了新的视野。

华南晚中生代广泛发育陆相沉积盆地,记录有大量的古土壤,其中,东南地区主要为钙质古土壤[10]。湖南茶陵盆地是白垩纪华南地区代表性陆相盆地之一,本次工作在其上白垩统发现了较为丰富的钙质古土壤。本文在进行钙质古土壤岩相和成壤钙质结核的阴极发光分析基础上,对钙质结核进行了碳氧同位素测试和大气方解石线(MCLs)甄别,以重建晚白垩世晚期低纬度的大气水氧同位素组成,为约束矫正同期全球水文循环模型提供重要基础数据。

1 地质背景中国东南地区中生代陆相沉积盆地经历了三个演化阶段:晚三叠世—早侏罗世类前陆盆地、中侏罗世裂谷盆地和晚侏罗世—白垩纪(可延伸到古近纪)断陷盆地[11-12]。其中,白垩纪时期的沉积盆地规模较小,多为数百平方千米,以裂谷盆地和/或断陷盆地为主[13]。

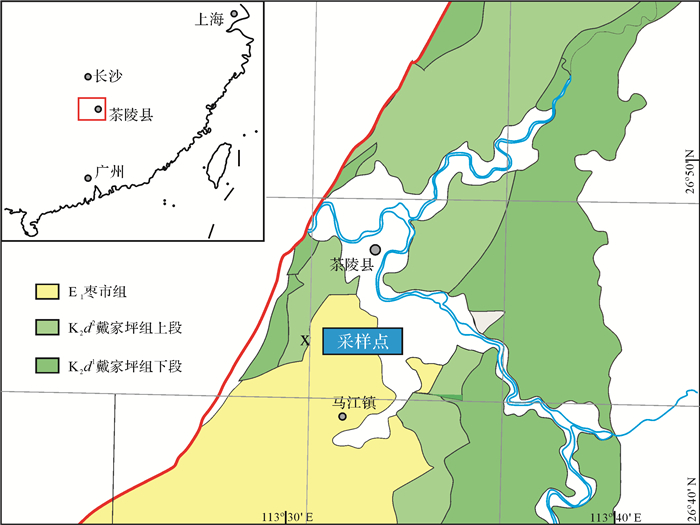

茶陵盆地位于湖南东南地区,是燕山期形成的北北东向长条形断陷山间盆地。盆地中主要发育上白垩统戴家坪组和古新统枣市组(图 1),其间呈假整合接触[14-15]。盆地东翼岩层厚度比西翼大,但西翼地层较东翼出露较完整、连续(图 1)。总体而言,戴家坪组以山麓洪积相与河流相为主,枣市组以湖相沉积为主[16]。

|

| 图 1 茶陵盆地地质略图及采样位置 (地质底图据湖南省地质局区测队,1966①简化) Figure 1 Geological sketch of Chaling Basin and observed section location (geological map simplified from Hunan Geological Survey, 1966①) |

① 湖南省地质局区测队.中华人民共和国区域地质调查报告报告,1:20万茶陵幅, 1966.

本次工作的对象为戴家坪组(K2d),因产恐龙蛋化石Oõlithes sp.①,故被认为属于晚白垩世晚期地层;它以副砾岩—粉砂质泥岩构成的旋回为特征。

①湖南省地质局区测队.中华人民共和国区域地质调查报告报告,1:20万茶陵幅,1966.

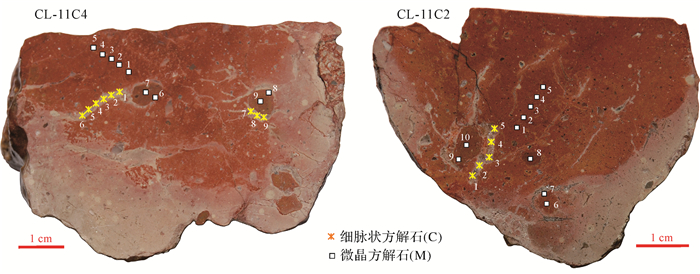

2 材料和方法观测剖面位于茶陵县西南方向约10 km处的新田村附近(图 1),起始点GPS坐标为26°43′43″N,113°31′48″E,发育古土壤段的地层厚约118 m。本次工作对该套地层进行了野外详细地层和岩相观察描述,在两套典型古土壤层中采集了大型成壤钙质结核2件样品(CL11-C2、CL-11C4),用于碳氧同位素测试分析。室内将样品清洗烘干后切割成相邻贴合的0.5 mm厚薄片和2~3 mm厚切片(图 2)以备阴极发光照射和碳氧同位素粉末取样之需。

|

| 图 2 大型成壤钙质结核切片及微钻粉末取样点位置图 Figure 2 Section images of large pedogenic calcrete samples and microdrilling locations |

薄片阴极发光测试在美国堪萨斯地质调查中心阴极发光实验室完成,测试仪器为Reliotron Ⅲ冷阴极发光仪,样品为不大于10 cm×10 cm的标准阴极发光薄片,束电压为10 kV,束电流为0.5 mA,样品仓内保护气为氦气,气压为50 μmHg。

切片磨平用于粉末取样。在微钻取样时,单个点取样直径限制在1~1.5 mm范围内,样品重一般0.5~1.0 mg。切面观察显示,钙质结核主要由两部分组成:浅红色和棕红色方解石。本次工作对2件钙质结核共取33个点粉末样品,即在CL11-C4和CL-11C2样品中各取15和18点粉末样品。其中,CL11-C4样品在浅灰色和棕红色(图片上分别显示浅灰和深灰)区域各采集了9个点,CL-11C2样品分别采集了5和10个点(图 2)。

碳酸盐粉末样品的碳氧同位素分析在南京大学内生金属矿床成矿机制研究国家重点实验室完成。实验仪器为Finnigan公司的Delta Plus XP连续流质谱仪。碳氧同位素的结果以δ13C和δ18O同位素比值VPDB标准化表示,精度高于0.2‰;计算出的大气水δ18O以维也纳海水(VSMOW)标准化表示。

3 结果 3.1 岩相与阴极发光发育钙质古土壤层的背景岩石主要为杂基含量较高的副砾岩,其杂基含量一般可达20%~30%,表明其形成于重力流条件,沉积于山麓洪积扇。在此岩相基础上的成壤作用形成了多套古土壤层,并以钙质古土壤为主,呈紫红色、紫灰色;钙质结核含量高,大多超过20%,甚至达50%以上;单个结核大,直径平均5~10 cm,少数可达20 cm;形状多呈姜状(图 3a);部分层位土壤层中淋滤构造发育,具白色碳酸钙斑点和条带(图 3b)。大多钙质结核由棕红色微晶方解石基质和浅红色方解石细脉(图 2)两部分构成。

|

| 图 3 茶陵盆地新田村剖面戴家坪组钙质古土壤野外照片 a.背景为副砾岩中发育的紫红色古土壤及钙质结核;b.古土壤层中的淋滤构造。注:淋滤层中见丰富的钙质结核;地质锤长29 cm Figure 3 Field photographs showing calcisols of the Daijiaping Formation in the Xintian Section, Chaling Basin a. reddish-purple paleosol and pedogenic calcretes within the paraconglomerate host; b. leaching structure within paleosol layer. Note: abundant calcretes found in leaching layer; hammer 29 cm in length |

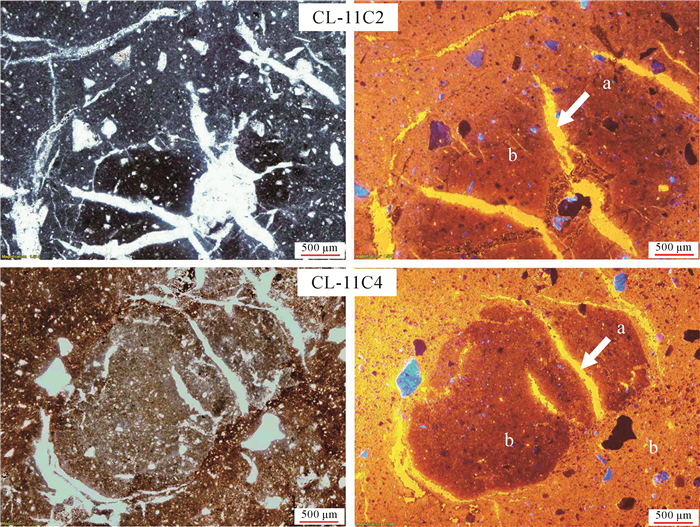

阴极发光结果显示:构成钙质结核主体的棕红色微晶方解石微弱发光呈橘红色,泥质含量较高者一般不发光;而裂隙中充填的浅红色细脉状方解石发光呈亮橘黄色(图 4)。两种不同阴极发光可能指示方解石的沉淀时间差异,即存在先后顺序。这一特征在两件样品CL-11C4和CL-11C2中表现均极其相似。

|

| 图 4 茶陵新田村剖面大型钙质结核CL-11C2和CL-11C4透射光(左)和阴极发光(右)图像 a.发光明亮橙黄色的细脉状方解石;b.发光微弱橘红色或不发光的基质 Figure 4 Matching transmitted light images (left) and cathodoluminescence (CL) images (right) from large calcrete samples CL-11C2 and CL-11C4 at Xintian Section, Chaling Basin a. CL bright orange vein calcite; b. CL dully or non-luminescence matrix |

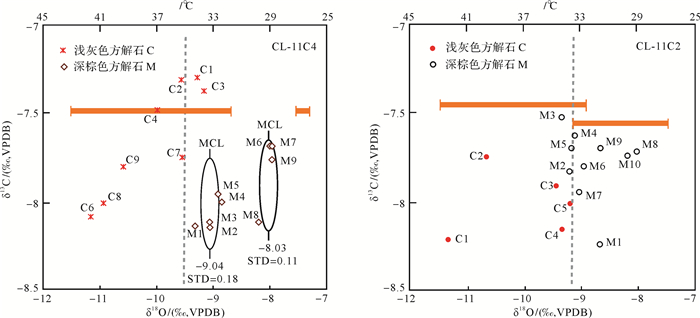

33个样品点测试结果显示,δ18O(VPDB)最大值为-7.96‰,最小值为-11.35‰;δ13C(VPDB)最大值为-7.30‰,最小值为-8.24‰。

样品CL-11C4的棕红色(图 2中深灰色)基质区域以较稳定的δ18O值和δ13C值为特征。其中,点M1~M5和M6~M9的δ18O值可识别出2条“大气方解石线”(meteoric calcite lines-MCLs)[5, 17-18],分别为(-9.04±0.18)‰, VPDB和(8.03±0.11)‰, VPDB(图 5、表 1)。浅红色(图 2中浅灰色)方解石脉区域的碳氧同位素结果相对复杂,δ18O(VPDB)偏轻,介于-9.16‰至-11.16‰。这种同位素分布趋势同样会出现在现代土壤的成壤方解石中[19]。

|

| 图 5 茶陵盆地戴家坪组成壤钙质结核方解石碳氧同位素相关图 取样点见图 2。图中灰色纵向虚线大致分隔了图 2中棕红色和浅红色区域样品的同位素分布;横向粗实线段代表两种成分推算出的温度分布范围;STD为标准差 Figure 5 C-O isotope crossplots of calcites of pedogenic calcretes of the Daijiaping Formation in the Chaling Basin Microdrilling numbers refer to Fig. 2. Gray short lines roughly separate isotope ranges of reddish-brown and light red spaces in Fig. 2. Coarse orange solid lines represent temperature ranges of two components; STD means standard deviations |

| 样品 | δ18O平均值/‰ | 标准差/‰ |

| CL-11C4 | -9.04 | 0.18 |

| CL-11C4 | -8.03 | 0.11 |

| CL-11C2 | -9.23—— | 0.84—— |

| 12a(Suarez et al., 2009) | -7.66 | 0.08 |

| 27(Suarez et al., 2009) | -8.71 | 0.17 |

| WN. 1.5 (Ross et al., 2017) | -8.39 | 0.58 |

| PRC-23 (Ludvigson et al., 2010) | -8.1 | 0.16 |

样品CL-11C2的稳定同位素分布模式存在类似特征:棕红色基质区域δ18O值(VPDB)-9.21‰~-8.03‰,较浅红色区域重,且较样品CL-11C4相对分散。其中,点M1~M10方差较大,为0.84,高于识别MCLs的最小标准差0.58要求(表 1),因此CL-11C2样品中难以辨识出MCLs;浅红色区域方解石δ18O值(VPDB)为-9.2‰~-11.35‰,而点C3~C5的δ18O与棕红色区域接近。

总体来看,两件样品棕红色与浅红色区域的δ13C值未显示明显差异(图 5)。

4 讨论与结论 4.1 钙质结核的两期方解石沉淀如前,一方面阴极发光图像显示钙质结核由两种发光特性的组份组成,即发光呈微弱橘红色的微晶方解石基质和亮橘黄色方解石脉(图 4);另一方面虽然碳同位素结果指示钙质结核这两个部分没有明显不同(图 5),均属成壤成因范围[20-22],但是氧同位素有一定的差别,这表明钙质结核存在先后两期的方解石结晶沉淀。

形成钙质结核的内因是在成壤条件下富集的CaCO3和古土壤BK层本身多孔性、易渗透性的特性,外因则是大气水淋滤作用。因此其形成机理可能是古土壤在富含CO2的地表径流和地下水的作用下,CaCO3被淋滤溶解,沿着古土壤疏松的结构下渗,并在垂向层面中留下痕迹(图 3b);当气候干旱蒸发作用强时会促使富CaCO3的孔隙水在渗流带产生沉淀。

钙质结核通常分布在沉积界面以下几米至几百米深[23-25]。戴家坪组成壤钙质结核的棕红色基质微弱发光呈橘红色甚至基本不发光,说明其时孔隙水中富游离氧,流体中Mn2+浓度较低。因此,我们认为这一期的方解石沉淀发生在离地表很近的古土壤层中,这个深度(古土壤BK层)可能是离地面不到10 m的渗流带上部到顶部的位置。

而结核裂缝中充填的方解石脉形成时间稍晚[9, 26],可能为构造沉降作用所致,并受到新的沉积物充填、气候变化的影响。无论成因如何,原先位处渗流带顶部的古土壤层埋藏深度发生了变化,且其深度可能较深或许可到达潜水面致使游离氧缺失、Mn2+进入方解石晶格进而沉淀,使得方解石呈亮橘黄色发光特征[9, 27]。虽然脉体组分δ18O更贫化的趋势对应准同生期埋藏作用,而2件样品δ13C值(VPDB)分别为(-7.86±0.22)‰和(-7.82±0.24)‰,仍然属于古土壤范畴[20-22]。因此,我们认为第二期方解石沉淀仍然与大气、生物呼吸和地表径流有联系,即与成壤作用有较大关系,其沉淀深度可能在渗流带内,或许仍然在渗流带的中上部。

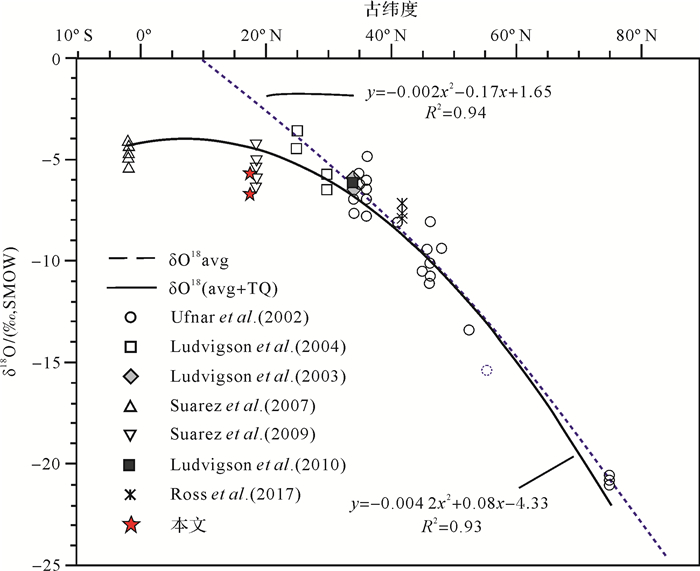

4.2 古降水氧同位素古气候重建中往往涉及气候与水文交互过程,其重要内容是查明关键带(Critical zone)的“大气水—古土壤”水—岩系统,目标之一是重建参与水—岩体系交互反应的成岩流体和大气降雨的δ18Ow组成。但是,传统的氧同位素温度计方法需要矿物生长温度和氧同位素δ18O[28]则较难实现这一目标,新的方法则可根据矿物的氧同位素δ18O值通过古纬度和方解石中MCLs值来求取并予以表征。Suarez et al.[5]首先尝试通过古纬度重建了北美白垩纪时期的古温度,进而推算了当时古降雨的δ18Ow值。这为我们进一步实施华南近于同期的古降水δ18Ow值求解提供了先例。

通常,古土壤在接受淋滤过程中大气水的δ18Ow信息会以MCLs的形式记录下来[7, 17]。研究区戴家坪组上部钙质结核内部两种不同碳酸盐组分形成于两个阶段,其中第一阶段棕红色的基质部分可能真正记录了大气水的氧同位素信息[9]。如前述结果,钙质结核样品CL-11C4基质部分识别出2条的MCLs,分别为(-9.04 ± 0.18)‰,VPDB和(-8.03±0.11)‰,VPDB(图 5),与Suarez et al.[5]北美近似纬度18~19°N的MCLs值近似(表 1),表明该样品基质部分的δ18O值符合进行推算古降水氧同位素的条件[17],而CL-11C2的基质部分碳氧同位素分布较为分散,不能识别出MCLs(图 5)(表 1中以删除线表示)。

要获取古降水的氧同位素,首先要获取低温矿物方解石形成时的地表古温度。该温度一般利用Spicer et al.[29]基于叶片化石地貌学数据[30]建立的温度纬度梯度经验公式[3]来获得。

(1)

(1)

其中, t代表温度(℃),l代表古纬度。此公式选择运用陆相叶片化石建立的温度梯度,一方面是考虑植物是直接与大气环境相接触的自然指标,所处环境与古土壤是一致的;另一方面,此公式是摒弃模型的纯经验公式[5]。

虽然湖南茶陵盆地目前没有古纬度数据,但是因茶陵盆地与南雄盆地的距离和相对位置在晚白垩世时和现在基本没有变化(两地现今纬度差约1.4°)。所以,借助广东南雄盆地晚白垩世的古纬度16°N[31]推测茶陵盆地的古纬度大致为17.4°N。基于叶片化石地貌学经验公式(1),求得茶陵盆地的年平均气温(MAT)为26.4 ℃。

由此,可基于氧同位素分馏方程和“方解石—水”分馏系数α[32]来估算获取大气水同位素组成:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

公式(2)中T为开尔文温度(T+273)。公式(3)反映了氧同位素分馏与结晶矿物和大气降水的氧同位素关系,亦即由于MCLs值反映的是大气水结晶分馏产生的方解石δ18O[17](即δA),故在求得古MAT的前提下可通过MCLs的值δA反推大气水同位素组成δ18Ow(即δB)。

由于样品CL-11C4存在2条MCLs,其δA(δ18O)(VPDB)分别为-7.30‰和-8.24‰,代入公式(3),从而估算出茶陵盆地晚白垩世晚期的大气降雨的δ18Ow(VSMOW)组成分别为-5.76‰和-6.80‰。该结果与北美近似古纬度位置(18°~19°N)获得的大气降雨δ18Ow(VSMOW)结果-5.09‰ ~ -6.40 ‰[5]近于一致(图 6),与Poulsen et al.[33]提出的模型中模拟的大气水δ18Ow(-4.0‰~-7.0‰,VSMOW)也较匹配,但与Ufnar et al.[3]最初拟合的北美地区中纬度—中高纬度的大气水—纬度的曲线(图 6)趋势相比,本文样品的δ18Ow贫化了~4.0 ‰(图 6),原因可能是研究区当时存在更强的降雨效应(rainout effect)或者蒸发作用[5],使得大气水表现为轻的氧同位素更为集中。

|

| 图 6 白垩纪中—晚期大气降水δ18Ow纬度梯度曲线(据Suarez et al.[5]和Ludvigson et al.[8]综合) 虚线及公式为Ufnar et al.[3]基于大气菱铁矿线MSL值拟合出的二次曲线;实线及公式则是前人所有数据加上本文成壤或早期成岩方解石MCL值拟合的二次曲线[3, 5, 7, 9, 34-36] Figure 6 Latitudinal gradient curves of meteoric water δ18Ow during the mid-late Cretaceous (composed from Suarez et al.[5] and Ludvigson et al.[8]) the orange dashed curve and equation fit to the MSL (meteoric sphaerosiderite line) by Ufnar et al.[3]; the black curve and equation fit to the MCLs of pedogenic or early diagenetic calcite by the published data plus this work |

基于上述估算的δ18Ow大气水组成,可以反过来验证钙质结核脉体方解石组分的准同生期埋藏作用。由于两期方解石形成深度差距不大,假定准同生成岩过程中孔隙水有着类似的δ18O组成,根据氧同位素温度计公式(2)和(3)可以演算反推,浅红色方解石脉体分馏时的古温度范围大致为32 ℃~43 ℃。可见在埋深水文条件改变后,潜水面附近地层可能埋藏温度比地表高6 ℃~17 ℃[7, 9](图 5),但不排除孔隙水也可能有少量其他较轻来源的流体混入。

由上估算过程及讨论我们认为,湖南茶陵盆地上白垩统上部戴家坪组中钙质结核不仅记录了古土壤的成壤信息,反映了生物作用(植物呼吸)、古大气、降雨、地表径流的综合效应,而且稳定氧同位素指针也揭示了其时北半球低纬度(~17.4°N)的古降水氧同位素值及其分馏信息,可为白垩纪中低纬度水文循环模型及古大气环流模拟提供数据参考,也可进一步约束前人的经验模型。

致谢 张朝凯博士、王旌羽参加了野外工作,相关实验得到了南京大学内生金属矿产成矿机制国家重点实验室的沈海燕老师和美国堪萨斯大学的ROSS博士帮助和支持,在此一并表示感谢!

| [1] |

Chahine M T. The hydrological cycle and its influence on climate[J]. Nature, 1992, 359(6394): 373-380. DOI:10.1038/359373a0 |

| [2] |

Barrick R E, Fischer A G, Showers W J. Oxygen isotopes from turtle bone:applications for terrestrial paleoclimates?[J]. PALAIOS, 1999, 14(2): 186-191. DOI:10.2307/3515374 |

| [3] |

Ufnar D F, González L A, Ludvigson G A, et al. The mid-Cretaceous water bearer:isotope mass balance quantification of the Albian hydrologic cycle[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2002, 188(1/2): 51-71. |

| [4] |

Ufnar D F, González L A, Ludvigson G A, et al. Evidence for increased latent heat transport during the Cretaceous (Albian) greenhouse warming[J]. Geology, 2004, 32(12): 1049-1052. DOI:10.1130/G20828.1 |

| [5] |

Suarez M B, González L A, Ludvigson G A, et al. Isotopic composition of low-latitude paleoprecipitation during the Early Cretaceous[J]. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2009, 121(11/12): 1584-1595. |

| [6] |

Suarez M B, González L A, Ludvigson G A. Estimating the oxygen isotopic composition of equatorial precipitation during the mid-cretaceous[J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 2010, 80(5): 480-491. DOI:10.2110/jsr.2010.048 |

| [7] |

Ludvigson G A, Joeckel R M, González L A, et al. Correlation of Aptian-Albian carbon isotope excursions in continental strata of the cretaceous Foreland Basin, eastern Utah, U.S.A[J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 2010, 80(11/12): 955-974. |

| [8] |

Ludvigson G A, Lez L A G, Fowle D A, et al. Paleoclimatic applications and modern process studies of pedogenic siderite 2013[J]. New Frontiers in Paleopedology and Terrestrial Paleoclimatology. SEPM Special Publication, 2013, 104: 79-87. |

| [9] |

Ross J B, Ludvigson G A, Möller A, et al. Stable isotope paleohydrology and chemostratigraphy of the Albian Wayan Formation from the wedge-top depozone, North American Western Interior Basin[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2017, 60(1): 44-57. |

| [10] |

李祥辉, 陈斯盾, 曹珂, 等. 浙闽地区白垩纪中期古土壤类型与古气候[J]. 地学前缘, 2009, 16(5): 63-70. [ Li Xianghui, Chen Sidun, Cao Ke, et al. Paleosols of the mid-Cretaceous:a report from Zhejiang and Fujian, SE China[J]. Earth Science Frontiers, 2009, 16(5): 63-70. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-2321.2009.05.006] |

| [11] |

Shu L S, Faure M, Wang B, et al. Late Palaeozoic-Early Mesozoic geological features of South China:response to the Indosinian collision events in Southeast Asia[J]. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 2008, 340(2/3): 151-165. |

| [12] |

Shu L S, Zhou X M, Deng P, et al. Mesozoic tectonic evolution of the Southeast China Block:new insights from basin analysis[J]. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2009, 34(3): 376-391. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2008.06.004 |

| [13] |

Chen Q M, Dickinson W R. Contrasting nature of petroliferous Mesozoic-Cenozoic basins in eastern and western China[J]. AAPG Bulletin, 1986, 70(3): 263-275. |

| [14] |

高红湘. 湖南茶陵盆地"红层"的划分[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1975, 13(2): 89-95. [ Gao Hongxiang. Paleocene mammal-bearing beds of Chaling Basin, Hunan[J]. Vertebtrata Palasiatica, 1975, 13(2): 89-95.] |

| [15] |

储澄. 湖南攸县、茶陵一带红色岩系[J]. 地层学杂志, 1978, 2(2): 146-151. [ Chu Cheng. Red beds of the Youxian-Chaling area in Hunan Province[J]. Acta Stratigraphica Sinica, 1978, 2(2): 146-151.] |

| [16] |

段嘉瑞, 彭恩生, 魏州龄. 湖南茶永盆地白垩-第三系红层岩相研究[J]. 大地构造与成矿学, 1978, 2(2): 13-41. [ Duan Jiarui, Peng Ensheng, Wei Zhouling. Study on the Cretaceous to Paleogene red beds facies in Cha Yong basin, Hunan[J]. Geotectonica et Metallogenia, 1978, 2(2): 13-41.] |

| [17] |

Lohmann K C. Geochemical patterns of meteoric diagenetic systems and their application to studies of paleokarst[M]. New York: Springer, 1988: 58-80.

|

| [18] |

Choquette P, James N. Limestones-the burial diagenetic environment[J]. Diagenesis:Geoscience Canada, Reprint Series, 1990, 4: 75-111. |

| [19] |

Mintz J S, Driese S G, Breecker D O, et al. Influence of changing hydrology on pedogenic calcite precipitation in Vertisols, Dance Bayou, Brazoria County, Texas, U.S.A.:implications for estimating paleoatmospheric pCO2[J]. Journal of Sedimentary Researc, 2011, 81(6): 394-400. DOI:10.2110/jsr.2011.36 |

| [20] |

Cerling T E, Quade J. Stable carbon and oxygen isotopes in soil carbonates[M]. Washington D.C.: American Geophysical Union, 1993: 217-231.

|

| [21] |

Alonso-Zarza A M. Palaeoenvironmental significance of palustrine carbonates and calcretes in the geological record[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2003, 60(3/4): 261-298. |

| [22] |

Li X H, Xu W L, Liu W H, et al. Climatic and environmental indications of carbon and oxygen isotopes from the Lower Cretaceous calcrete and lacustrine carbonates in Southeast and Northwest China[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2013, 385: 171-189. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.03.011 |

| [23] |

Dix G R, Mullins H T, Mozley P S, et al. Oxygen and carbon isotopic composition of marine carbonate concretions:an overview-discussion and reply[J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 1993, 63(5): 1007-1008. DOI:10.1306/D4267C71-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865D |

| [24] |

庞谦, 李凌, 胡广, 等. 川北地区下寒武统筇竹寺组钙质结核特征及成因机制[J]. 沉积学报, 2017, 35(4): 681-690. [ Pang Qian, Li Ling, Hu Guang, et al. Characteristics and genetic mechanism of calcareous concretions in the early Cambrian Qiongzhusi formation of northern Sichuan Basin[J]. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica, 2017, 35(4): 681-690.] |

| [25] |

Bojanowski M J, Barczuk A, Wetzel A. Deep-burial alteration of early-diagenetic carbonate concretions formed in Palaeozoic deep-marine greywackes and mudstones (Bardo Unit, Sudetes Mountains, Poland)[J]. Sedimentology, 2014, 61(5): 1211-1239. DOI:10.1111/sed.2014.61.issue-5 |

| [26] |

Raiswell R. The growth of Cambrian and Liassic concretions[J]. Sedimentology, 1971, 17(3/4): 147-171. |

| [27] |

Boggs S, J r, Krinsley D. Application of cathodoluminescence imaging to the study of sedimentary rocks[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006: 165.

|

| [28] |

Urey H C. The thermodynamic properties of isotopic substances[J]. Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed), 1947, 562-581. DOI:10.1039/jr9470000562 |

| [29] |

Spicer R A, Corfield R M. A review of terrestrial and marine climates in the Cretaceous with implications for modelling the 'Greenhouse Earth'[J]. Geological Magazine, 1992, 129(2): 169-180. DOI:10.1017/S0016756800008268 |

| [30] |

Wolfe J A, Upchurch G R Jr. North American nonmarine climates and vegetation during the Late Cretaceous[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1987, 61: 33-77. DOI:10.1016/0031-0182(87)90040-X |

| [31] |

杨卫东, 陈南生, 倪师军, 等. 白垩纪红层碳酸盐岩和恐龙蛋壳碳氧同位素组成及环境意义[J]. 科学通报, 1993, 38(23): 2161-2163. [ Yang Weidong, Chen Nansheng, Ni Shijun, et al. Carbon and oxygen isotopic compositions of the carbonate rocks and the dinosaur eggshells in the cretaceous red beds and their implication for paleoenvironment[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1993, 38(23): 1985-1989.] |

| [32] |

Friedman I, O'Neil J R. Compilation of stable isotope fractionation factors of geochemical interest[M]. Washington D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1977: 12.

|

| [33] |

Poulsen C J, Pollard D, White T S. General circulation model simulation of the δ18O content of continental precipitation in the middle Cretaceous:a model-proxy comparison[J]. Geology, 2007, 35(3): 199-202. DOI:10.1130/G23343A.1 |

| [34] |

Suarez M, González L A, Ludvigson G A, et al. Pedogenic sphaerosiderites from the Caballos Formation (Aptian-Albian) of Colombia: a stable isotope proxy for Cretaceous paleoequatorial precipitation[C]//Joint South-Central and North-Central Sections, both conducting their 41st annual meeting. Lawrence, Kansas: Geological Society of America, 2007: 75.

|

| [35] |

Ludvigson G A, Ufnar D F, González L A, et al. Terrestrial paleoclimatology of the Mid-Cretaceous greenhouse: I. cross-calibration of pedogenic siderite & calcite δ18O proxies at the Hadley cell boundary[C]//2004 Denver annual meeting. Denver, Colorado: Geological Society of America, 2004: 305.

|

| [36] |

Ludvigson G A, Gonzalez L A, Ufnar D F. The enigma of polar warmth in greenhouse worlds: insights from the Mid-Cretaceous terrestrial paleoclimatology of North America[C]//North-Central Section-37th annual meeting. Kansas City, Missouri: Geological Society of America, 2003: 52.

|

2018, Vol. 36

2018, Vol. 36