扩展功能

文章信息

- 程良清, 宋友桂, 李越, 张治平

- CHENG LiangQing, SONG YouGui, LI Yue, ZHANG ZhiPing

- 粒度端元模型在新疆黄土粉尘来源与古气候研究中的初步应用

- Preliminary Application of Grain Size End Member Model for Dust Source Tracing of Xinjiang Loess and Paleoclimate Reconstruction

- 沉积学报, 2018, 36(6): 1148-1156

- ACTA SEDIMENTOLOGICA SINCA, 2018, 36(6): 1148-1156

- 10.14027/j.issn.1000-0550.2018.087

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-09-18

- 收修改稿日期: 2017-12-02

2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

3. 中国科学院中亚生态与环境研究中心, 乌鲁木齐 830011;

4. 新疆伊犁哈萨克自治州环境监测站, 新疆伊宁 835000

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

3. Research Center for Ecology and Environment Central Asia, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China;

4. Environmental Monitoring Station of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Yining, Xinjiang 835000, China

粒度作为一个反映物源、搬运方式和古气候的重要指标,已被广泛地应用于海洋[1-3]、湖泊[4-5]以及黄土[6-8]古环境变化研究中。一般情况下,沉积物是不同物源或沉积动力过程作用的结果,单一的动力过程产生单一的粒度组分,全样的粒度参数只能近似地指示沉积环境的变化。因此,如何从全样的粒度频率分布曲线中分离出不同的单一粒度组分,进而探讨各组分的沉积学意义成为古环境研究的关键技术问题。目前黄土粒度组分分离方法主要有3种:1)Weibull分布函数拟合法:通过Weibull函数对沉积物中粒度频率分布曲线峰值进行拟合,从而分离出不同成因的粒度组分[9]。2)粒级—标准偏差法:计算每一粒级的所有样品数据的标准偏差,某一粒级所对应的标准偏差越大,说明产生该粒级的沉积动力或沉积过程等环境变化越大[2, 10]。3)端元模型分析法(EMMA):认为沉积物的粒度分布由不同物源或者不同传输机制和路径决定,每一种过程具有某一特征的粒级组合。与Weibull函数拟合方法不同,该方法主要基于主成分分析、因子旋转和非负最小二乘法来获得对应于某种沉积过程的组分,并且不需要任何特定条件的假设,主要根据样品的粒度总体分布特征进行分解[11]。尽管上述不同的粒度组分分离方法在黄土高原地区得到了成功的应用[10, 12-13],但是在中亚干旱区气候变化重建过程中鲜见报道。中亚干旱区同时受西风环流、西伯利亚高压以及北冰洋极锋等气候系统的影响,因而可能记录了更为复杂的沉积动力过程。本文以地处中亚干旱区的伊犁盆地肖尔布拉克黄土剖面为研究对象,尝试利用粒级标准偏差法和贝叶斯粒度端元模型法提取环境敏感粒度组分,探讨其粉尘来源与气候环境意义。

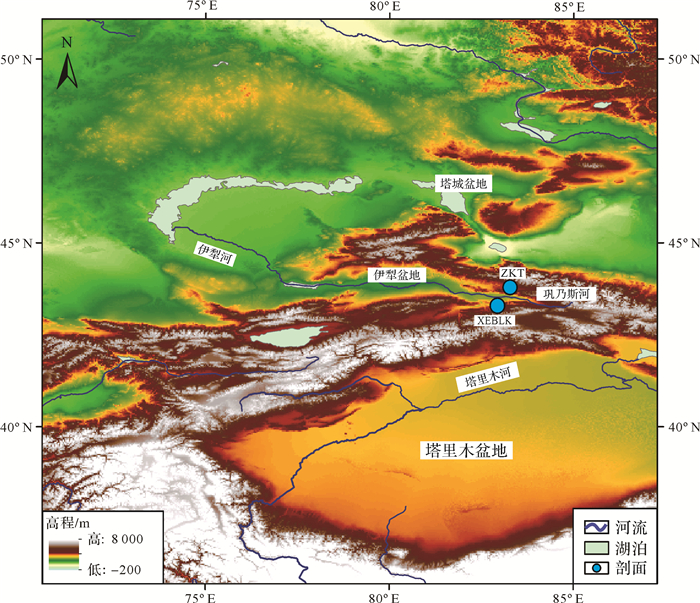

1 地理背景与剖面描述伊犁盆地为天山中部的一个山间盆地,其主要包括哈萨克斯坦东南部以及我国新疆伊犁地区(图 1)。地貌形态为向西敞开的喇叭形,地势上东高西低。区内沉积了大量的第四纪松散沉积物。由于其远离海洋,主要为半干旱的大陆性气候[14],独特的喇叭口形态使得来自大西洋以及地中海、里海的水汽被西风带到本区形成降水[15],因此本区的降水相对新疆其他地区较为丰富,年降水量在平原地区为200~500 mm,在山区可达到1 000 mm[14, 16]。盆地年均温为2.6 ℃~10.4 ℃,在1 500 m以上高空常年盛行西风[15],低空地面风以东风频率最高,但是大风主要以西和偏西风为主[17]。

|

| 图 1 伊犁盆地肖尔布拉克和则克台黄土剖面位置图 Figure 1 Locations of the Xiaoerbulake (XEBLK) and Zeketai (ZKT) loess sections in the Ili Basin |

肖尔布拉克剖面(XEBLK)(经纬度:83.07°E,43.42°N;海拔:902 m)位于伊犁盆地新源县西南的肖尔布拉克镇,坐落在巩乃斯河南岸的第四级河流阶地上。厚30.7 m,未见底,该剖面为约30 ka以来的黄土沉积[18]。粒度样品以5 cm为间隔采集,共计614个粒度样品。剖面描述如下:

0~0.7 m:表层土壤,浅黄棕色,松散,具块状和团粒结构,含大量的蜗牛以及较细的草根。

0.7~9 m:黄土,浅灰黄色粉砂,偶见层状结构和碳酸钙斑点。

9~12 m:弱古土壤,浅黄棕色,无层理,具颗粒结构。

12~27 m:黄土,浅灰黄色粉砂,偶见层状结构和碳酸钙斑点。

27~30.7 m:古土壤,红至深棕色,细小(< 0.5 cm)的碳酸钙结核较为常见,可见氧化锰薄膜。

2 实验方法粒度测试方法:称取干样品4 g左右放入80 mL烧杯,加入20 mL浓度为10%的盐酸,煮沸去掉碳酸盐;再加入20 mL浓度为15%的双氧水,煮沸去除有机质。加入20 mL浓度为0.05 mol/L的六偏磷酸钠分散剂,放在超声波震荡仪上震动15 min,最后上机测量。所有样品的粒度分析在黄土与第四纪地质国家重点实验室的英国Malvern公司生产的Mastersizer 2000型激光粒度仪上测量完成。

数据处理方法:

(1) 粒级标准偏差法。以粒级为横坐标,以每一粒级的所有样品数据计算的标准偏差为纵坐标,作粒级标准偏差图[2, 19]。某一粒级所对应的标准偏差越大,说明产生该粒级的沉积动力或沉积过程等环境变化越大。

(2) 贝叶斯粒度端元模型法(BEMMA)。Weibull函数拟合方法仅仅对单个样品的粒度分布曲线进行分解,没考虑到粒度分布的地质背景,因而并不能很好地解释组分的沉积动力过程。EMMA主要根据样品的粒度总体分布特征进行分解,使得每个端元的解释在统计学和物理学的意义上更具可描述性。但是EMMA方法也存在着端元数量的选择以及数据标准化过程中出现不确定性等问题。贝叶斯模型将模型参数作为随机变量,其灵活性高,并且可以有效地减少模型参数的不确定性,贝叶斯模型被广泛用于环境水文和地球化学数据的分析[20-21]。Yu et al.[22]将贝叶斯模型与沉积物粒度端元分析相结合,基于MATLAB语言提出了BEMMA方法,有效地减少了粒度端元数量的选择以及降低了算法的不确定性。因此,本研究采用BEMMA方法进行沉积动力过程的分离(具体的理论和计算过程参见参考文献[22])。

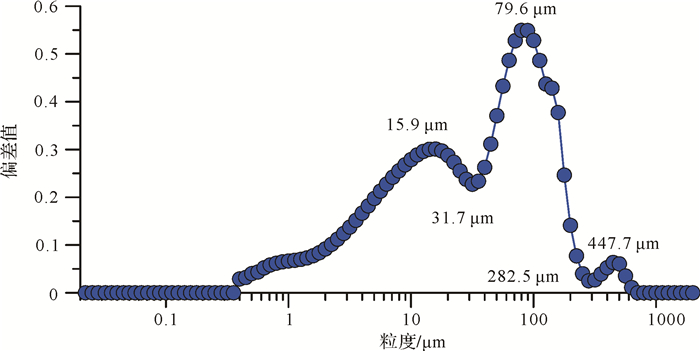

3 结果和讨论 3.1 粒级标准偏差分析根据XEBLK剖面全样粒度数据作出粒级标准偏差曲线(图 2)。从图 2可以看出,主要存在3个标准偏差峰值,分别出现在15.9 μm、79.6 μm和447.7 μm。所对应的粒度组分分别为0.4~31.7 μm,31.7~282.5 μm,282.5~709.6 μm。

|

| 图 2 XEBLK剖面粒级标准偏差曲线 Figure 2 Standard deviation curve of XEBLK loess section |

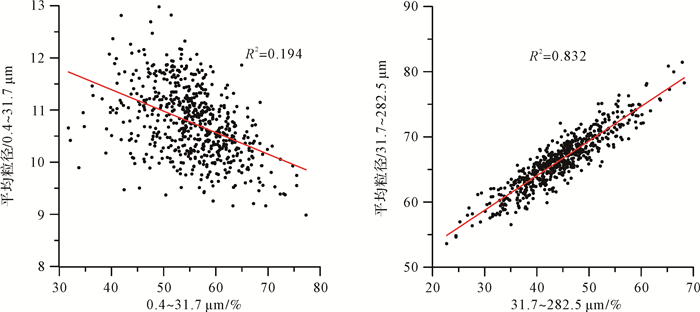

不同的粒度组成具有不同的环境意义[2, 10],图 3显示,282.5~709.6 μm组分主要在沉积物较粗时出现,可能记录了特大尘暴事件,0.4~31.7 μm组分与31.7~282.5 μm组分呈相反的变化趋势。组分含量不可避免地会受到各组分含量之间的相互影响,而粒度的大小与风力强度有很大关系[6, 23],通过分析组分含量与各自平均粒径的相关性可以有效地辨识气候敏感组分[24],31.7~282.5 μm组分与平均粒径的相关性非常好(R2=0.832)(图 4),而0.4~31.7 μm组分与平均粒径的相关性比较差(R2=0.194),相关性分析也说明31.7~282.5 μm的组分含量变化可能对气候变化较为敏感,而0.4~31.7 μm组分含量可能受其他组分含量的影响较大。因此31.7~282.5 μm的粗组分是对气候变化较为敏感的组分,更能反映沉积环境的变化。在黄土高原地区,鹿化煜等[25]通过将多种粒度组分与深海氧同位素进行对比,也发现>30 μm的粗颗粒含量是反映东亚冬季风的敏感指标。葛本伟等[24]利用粒级标准偏差法对天山北坡的黄土粒度进行研究后同样认为大于31.7 μm的组分是反映气候变化敏感的粒度组分。

|

| 图 4 0.4~31.7 μm和31.7~282.5 μm组分与各自平均粒径的相关性分析 Figure 4 Correlation analysis of 0.4-31.7 μm and 31.7-282.5 μm fractions with their respective mean grain size |

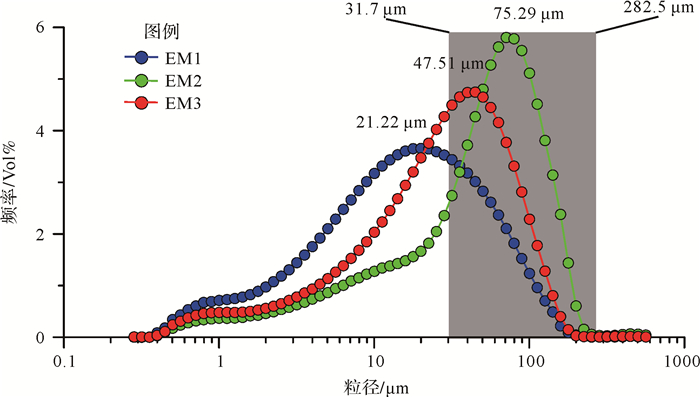

根据Yu et al.[22]提出的BEMMA方法,我们将XEBLK黄土粒度分离出3种粒度端元组分(EM),即EM1,EM3,EM2,对应的众数粒径分别为21.22 μm,47.51 μm和75.29 μm(图 5)。黄土层中,EM2和EM3的含量高,古土壤或弱古土壤层中,EM2和EM3的含量相对较低,而EM1的含量相对较高(图 3)。EM2(平均粒径[26]:40.67 μm)组分比较粗,而EM1(平均粒径:15.27 μm)和EM3(平均粒径:25.48 μm)组分偏细。Vandenberghe[27]通过归纳前人的研究成果,分析了沉积环境与组分众数粒径的关系(详细见Vandenberghe[27]),为我们分析端元组分的沉积动力过程提供了基础。

|

| 图 5 EM1、EM2和EM3频率分布曲线 Figure 5 Frequency distribution curves of EM1, EM2 and EM3 |

EM1组分:对应于Vandenberghe[27]提出的1.c.1的组分(约19 μm)类型,该组分不仅在中国黄土高原黄土粒度端元分布当中十分常见[27],在青藏高原东北部的祁连山黄土[28]、欧洲黄土古土壤序列[29-30]以及塔吉克斯坦黄土[31]当中也是比较常见的粒度组分。有研究表明,细颗粒碎屑可能会粘附在较粗颗粒碎屑表面,或者以聚合体的形式随着较粗颗粒一起经历搬运沉积过程[32-33]。然而,EM1组分与中值粒径之间表现出负的相关性,因此,“粘附”或“聚合体”假说可能并不能解释EM1组分的出现和含量的变化。尽管成壤风化作用也会产生较多的细颗粒碎屑[34],然而成壤风化作用中产生的碎屑颗粒通常在2 μm以下[35]。同时在伊犁半干旱区成壤作用很弱。因此,EM1组分也不是在成壤风化作用过程中产生的。在现代降尘实验中发现EM1组分主要以较为稳定的悬移组分出现[36],在尘暴活动的沉积物当中也占了相当的比例[33, 37]。该组分的平均粒径为15.27 μm,而平均粒径 < 20 μm的组分一旦起动则很容易上升到高层大气并分散到不同高空的大气中被高空气流带到下风区的任一上空[38]。Yang et al.[28]发现祁连山黄土主要存在3个端元组分,并认为众数粒径为16 μm的组分主要由西风搬运。因此,该组分很有可能为大气粉尘的较为稳定的背景值,反映了西风环流的信息。

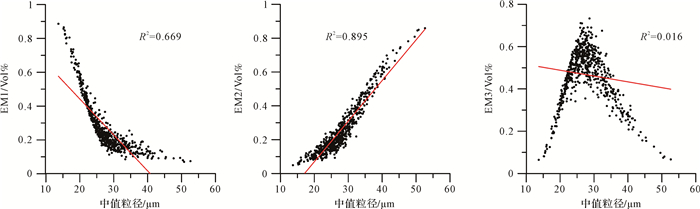

EM2组分:该组分对应于Vandenberghe[27]提出的1 a的组分(约75 μm)类型,该组分在河流阶地粉尘沉积物的粒度端元中比较常见,也是其主要成分,如在我国湟水河[31, 39]和黄河[29],塞尔维亚的多瑙河和蒂萨河[29]以及美国的密西西比河[40]的河流阶地附近堆积的黄土沉积物中均为主要成分。对比则克台黄土剖面(ZKT)(图 1)的粒度发现,XEBLK剖面的粒度比ZKT剖面的粒度要粗得多[41-42],ZKT剖面由于其位于巩乃斯河北岸,而伊犁河谷近地面大风风向主要为西风或偏西风,相应的河流沉积物供应相对较少,XEBLK剖面处于河流南岸,大风风向的下风向,同时受到天山山麓的阻挡,接受了较厚较粗的黄土沉积,因此,XEBLK剖面的黄土粗组分含量高主要与近源的河流沉积物多有关。EM2组分的平均粒径为40.67 μm,而平均粒径为20~70 μm的粉砂组分,在一般的尘暴中可上升到近地表几百米以内,搬运距离大致在1 000 km以内[38],也说明EM2可能主要为河流沉积物近距离悬移搬运的组分。从图 5可以看出通过粒级标准偏差法计算的敏感组分31.7~282.5 μm在EM2组分中的含量最高(EM2组分曲线与横坐标轴之间重叠的阴影部分面积最大)。并且EM1,EM2,EM3组分分别与中值粒径[18]的相关性分析显示(图 6),EM3的相关性最差(R2=0.016),EM1次之(R2=0.669),而EM2具有最显著的相关性(R2=0.895)。因此,推断EM2是反映气候变化较为敏感的粒度组分,主要反映近地面风强度的变化。

|

| 图 6 EM1、EM2以及EM3与中值粒径的相关性分析 Figure 6 Correlations of EM1, EM2 and EM3 with median grain size |

EM3组分:该组分对应于Vandenberghe[27]提出的1.b.1的组分(44~65 μm)类型,该组分在黄土高原黄土中非常典型,其含量主要表现为由近源区的黄土高原北部向远源区的南部含量逐渐降低[13, 43]。EM3组分的平均粒径为25.48 μm,EM3组分可能也主要为近距离的悬移搬运[38]。Crouvi et al.[44]通过分析以色列南部Negev沙漠中的3个黄土剖面的粒度组成,并结合风向,粒度的空间变化,物源的可及性分析认为众数粒径为50~60 μm组分主要为砂粒级组分的碰撞磨蚀产生。因此,我们推测其主要是在尘暴活动中,较粗的颗粒被大风扬起,其后在搬运过程中,颗粒之间相互碰撞磨蚀产生。

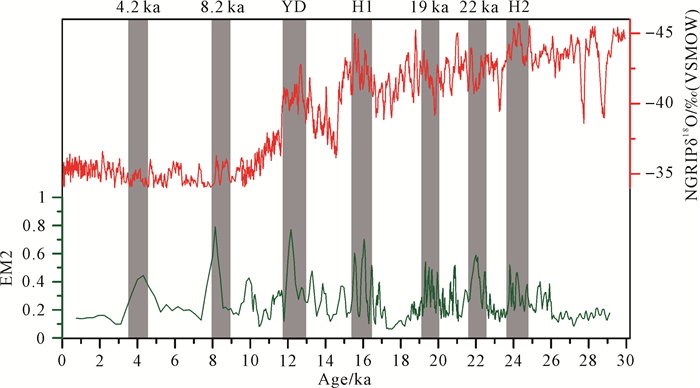

3.3 端元组分在古气候环境重建中的应用根据粒度组分变化特征,初步重建该剖面30 ka以来的气候环境变化历史。在深海氧同位素3a阶段(MIS3a,30~26 ka),EM1组分含量较高,EM2组分处于较为稳定的低值,282.5~709.6 μm组分含量也较少(图 3),说明MIS3a晚期西风环流对伊犁地区影响较大,西风携带来的水汽较多,古土壤发育,地表风的强度较弱,强沙尘暴天气少。末次冰盛期(LGM,26~18 ka),EM2组分处于较为稳定的髙值,EM1明显减少,282.5~709.6 μm组分含量明显增多,说明在LGM时期西伯利亚高压增强,低空气流风力较强,搬运粉尘能力增加,强沙尘暴频发,西风带南移,西风环流对伊犁地区的影响相对变弱。末次冰消期(18~11 ka),18~17 ka期间,EM1组分含量迅速增加,EM2组分含量迅速减少,未见282.5~709.6 μm组分。说明此期间,西风环流对伊犁地区的影响较大,西风携带来的水汽较多,弱古土壤发育,西伯利亚高压较弱,低空气流风力较弱,强沙尘暴极少。17~11 ka期间EM1组分含量处于一个较为稳定的低值,而EM2组分的变化幅度较大,说明该时期西风带南移,西风环流对伊犁地区的影响较小,低空风力波动幅度较大。全新世时期(11 ka以来),与17~11 ka期间的组分含量相比,EM1组分含量相对增高,EM2组分含量相对降低,282.5~709.6 μm组分减少,说明与17~11 ka期间相比,全新世期间西风对伊犁盆地的影响较大,低空气流风力较弱。早全新世282.5~709.6 μm组分含量要高于中晚全新世表明了早全新世强尘暴频率比中晚全新世要高。

不同纬度的太阳辐射量变化存在着差异,高纬地区太阳辐射量变化幅度比低纬地区要大。冰期高纬地区降温大于低纬地区,经向温度梯度增加,风力加强。而EM2组分的含量与风力强度有很大关系,因此,EM2组分也能够间接指示温度的变化。将XEBLK剖面30 ka以来的EM2组分含量变化与格陵兰冰芯δ18O记录对比,发现EM2组分记录了7个明显的峰值,其中3个峰值可分别对应格陵兰冰芯记录中的H1、H2、YD事件,另外4个峰值分别出现在4.2 ka、8.2 ka、19 ka和22 ka(图 7)。EM2组分记录的YD事件和H1事件的变化幅度明显大于H2事件,可能是区域气候与全球气候综合作用的结果。在北半球多个地方均发现4.2 ka事件的记录[45],其被认为可能是造成新石器文化衰败的主要原因[46-48]。Li et al.[16]通过分析伊宁尼勒克湖泊沉积物的孢粉记录发现,伊犁地区在5.2~3.3 ka之间处于极度干旱时期,主要以荒漠草原为主。邻近伊犁赛里木湖、巴里坤湖、托勒库勒湖以及准格尔盆地玛纳斯湖的沉积记录指示在4.5 ka左右处于寒冷干旱时期[49-52],然而黄土中的记录相对缺乏。因此本研究提供了新疆黄土记录的4.2 ka寒冷干旱事件的证据。8.2 ka事件在北半球多处均有记录[47, 53-54],新疆地区的艾比湖[55]、博斯腾湖[56]以及巴里坤湖[57]的沉积记录表明8.2 ka事件期间,该区可能处于寒冷湿润的气候环境之下。我们的记录表明该时期EM2组分含量增加(图 7),变化特征同4.2 ka事件期间较为相似(都处于高值),这也证实了EM2组分可能反映温度的变化。在其他地区还未有19 ka事件和22 ka事件的记录,因此本研究中EM2在19 ka和22 ka期间处于峰值的原因,还需要更多的指标和年代学工作来解释。

通过粒级标准偏差法和端元模型法初步探讨了XEBLK剖面的古气候的粒度敏感组分,主要得出以下结论:

(1) EM2组分是较为敏感的古气候指标,主要代表了近距离的悬移搬运组分,主要来自近源河流沉积物堆积。EM1组分代表大气粉尘中较为稳定的背景值,与西风环流有关。EM3组分也代表了近距离的悬移搬运成分,可能主要由较粗颗粒的碰撞磨蚀产生。

(2) EM2组分记录了MIS2阶段以来的气候波动事件,如H事件、YD事件。

(3) 贝叶斯粒度端元模型能够区分不同的沉积动力过程,在新疆黄土古气候研究具有广泛的应用前景。

| [1] |

孙有斌, 高抒, 李军. 边缘海陆源物质中环境敏感粒度组分的初步分析[J]. 科学通报, 2003, 48(1): 83-86. [ Sun Youbin, Gao Shu, Li Jun. Preliminary analysis of grain-size populations with environmentally sensitive terrigenous components in marginal sea setting[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48(1): 83-86. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.2003.01.021] |

| [2] |

Boulay S, Colin C, Trentesaux A, et al. Mineralogy and sedimentology of pleistocene sediment in the South China Sea (ODP Site 1144)[C]//Prell W L, Wang P, Blum P, et al. Proceedings of the ocean drilling program, scientific results, 2003, 184: 1-21.

|

| [3] |

Stuut J B W, Temmesfeld F, De Deckker P. A 550ka record of aeolian activity near North West Cape, Australia:Inferences from grain-size distributions and bulk chemistry of SE Indian Ocean deep-sea sediments[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 83: 83-94. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.003 |

| [4] |

Liu X X, Vandenberghe J, An Z S, et al. Grain size of lake qinghai sediments:Implications for riverine input and holocene monsoon variability[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2016, 449: 41-51. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.005 |

| [5] |

Peng Y J, Xiao J L, Nakamura T, et al. Holocene East Asian monsoonal precipitation pattern revealed by grain-size distribution of core sediments of Daihai Lake in Inner Mongolia of north-central China[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 233(3/4): 467-479. |

| [6] |

Ding Z L, Derbyshire E, Yang S L, et al. Stacked 2.6-Ma grain size record from the Chinese loess based on five sections and correlation with the deep-sea δ18O record[J]. Paleoceanography, 2002, 17(3): 5. |

| [7] |

Lu H Y, Zhang F Q, Liu X D, et al. Periodicities of palaeoclimatic variations recorded by loess-paleosol sequences in China[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2004, 23(18/19): 1891-1900. |

| [8] |

An Z S. The history and variability of the East Asian paleomonsoon climate[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2000, 19(1/2/3/4/5): 171-187. |

| [9] |

Sun D H, Bloemendal J, Rea D K, et al. Grain-size distribution function of polymodal sediments in hydraulic and aeolian environments, and numerical partitioning of the sedimentary components[J]. Sedimentary Geology, 2002, 152(3/4): 263-277. |

| [10] |

徐树建, 潘保田, 高红山, 等. 末次间冰期-冰期旋回黄土环境敏感粒度组分的提取及意义[J]. 土壤学报, 2006, 43(2): 183-189. [ Xu Shujian, Pan Baotian, Gao Hongshan, et al. Analysis of grain-size populations with environmentally sensitive components of loess during the last interglacial-glacial cycle and their implications[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2006, 43(2): 183-189. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0564-3929.2006.02.002] |

| [11] |

Weltje G J. End-member modeling of compositional data:Numerical-statistical algorithms for solving the explicit mixing problem[J]. Mathematical Geology, 1997, 29(4): 503-549. DOI:10.1007/BF02775085 |

| [12] |

Sun D, Bloemendal J, Rea D K, et al. Bimodal grain-size distribution of Chinese loess, and its palaeoclimatic implications[J]. Catena, 2004, 55(3): 325-340. DOI:10.1016/S0341-8162(03)00109-7 |

| [13] |

Prins M A, Vriend M, Nugteren G, et al. Late quaternary aeolian dust input variability on the Chinese Loess Plateau:Inferences from unmixing of loess grain-size records[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2007, 26(1/2): 230-242. |

| [14] |

Song Y G, Chen X L, Qian L B, et al. Distribution and composition of loess sediments in the Ili Basin, Central Asia[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 334-335: 61-73. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.12.053 |

| [15] |

叶玮. 新疆西风区黄土沉积特征与古气候[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 2001: 1-179. [ Ye Wei. Loess deposition features and paleoclimate in the westerlies-dominated region of Xinjiang[M]. Beijing: Ocean Press, 2001: 1-179.]

|

| [16] |

Li X Q, Zhao K L, Dodson J, et al. Moisture dynamics in Central Asia for the last 15kyr:New evidence from Yili Valley, Xinjiang, NW China[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2011, 30(23/24): 3457-3466. |

| [17] |

史正涛.新疆伊犁黄土地层形成时代及环境研究[D].西安: 中国科学院地球环境研究所, 2005. [Shi Zhengtao. Age of Yili loess in Xijiang and its paleoenvironmental implications[D]. Xi'an: Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2005.]

|

| [18] |

Li Y, Song Y G, Lai Z P, et al. Rapid and cyclic dust accumulation during MIS 2 in Central Asia inferred from loess OSL dating and grainsize analysis[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 32365. DOI:10.1038/srep32365 |

| [19] |

陈桥, 刘东艳, 陈颖军, 等. 粒级-标准偏差法和主成分因子分析法在粒度敏感因子提取中的对比[J]. 地球与环境, 2013, 41(3): 319-325. [ Chen Qiao, Liu Dongyan, Chen Yingjun, et al. Comparative analysis of grade-standard deviation method and factors analysis method for environmental sensitive factor analysis[J]. Earth and Environment, 2013, 41(3): 319-325.] |

| [20] |

Napier G, Neocleous T, Nobile A. A composite bayesian hierarchical model of compositional data with zeros[J]. Journal of Chemometrics, 2015, 29(2): 96-108. DOI:10.1002/cem.v29.2 |

| [21] |

Parnell A C, Phillips D L, Bearhop S, et al. Bayesian stable isotope mixing models[J]. Environmetrics, 2013, 24(6): 387-399. |

| [22] |

Yu S Y, Colman S M, Li L X. BEMMA:A hierarchical bayesian end-member modeling analysis of sediment grain-size distributions[J]. Mathematical Geosciences, 2016, 48(6): 723-741. DOI:10.1007/s11004-015-9611-0 |

| [23] |

Xiao J, Porter S C, An Z, et al. Grain Size of Quartz as an Indicator of Winter Monsoon Strength on the Loess Plateau of Central China during the Last 130, 000 Yr[J]. Quaternary Research, 1995, 43: 22-29. DOI:10.1006/qres.1995.1003 |

| [24] |

葛本伟, 刘安娜. 天山北麓黄土沉积的光释光年代学及环境敏感粒度组分研究[J]. 干旱区资源与环境, 2017, 31(2): 110-116. [ Ge Benwei, Liu Anna. Optically stimulated luminescence dating and analysis of environmentally sensitive grain-size component of loess in the northern slope of Tian Shan[J]. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 2017, 31(2): 110-116.] |

| [25] |

鹿化煜, 安芷生. 洛川黄土粒度组成的古气候意义[J]. 科学通报, 1997, 42(1): 67-69. [ Lu Huayu, An Zhisheng. Pretreated methods on loess-palaeosol samples granulometry[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, 42(1): 67-69.] |

| [26] |

Folk R L, Ward W C. Brazos River bar:A study in the significance of grain size parameters[J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 1957, 27(1): 3-26. DOI:10.1306/74D70646-2B21-11D7-8648000102C1865D |

| [27] |

Vandenberghe J. Grain size of fine-grained windblown sediment:A powerful proxy for process identification[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2013, 121: 18-30. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.03.001 |

| [28] |

Yang F, Zhang G L, Yang F, et al. Pedogenetic interpretations of particle-size distribution curves for an alpine environment[J]. Geoderma, 2016, 282: 9-15. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.07.003 |

| [29] |

Bokhorst M P, Vandenberghe J, Sümegi P, et al. Atmospheric circulation patterns in central and eastern europe during the weichselian pleniglacial inferred from loess grain-size records[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 234(1/2): 62-74. |

| [30] |

Varga G. Similarities among the Plio-Pleistocene terrestrial aeolian dust deposits in the World and in Hungary[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 234(1/2): 98-108. |

| [31] |

Vandenberghe J, Renssen H, Van Huissteden K, et al. Penetration of Atlantic westerly winds into Central and East Asia[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2006, 25(17/18): 2380-2389. |

| [32] |

Falkovich A H, Ganor E, Levin Z, et al. Chemical and mineralogical analysis of individual mineral dust particles[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres, 2001, 106(D16): 18029-18036. DOI:10.1029/2000JD900430 |

| [33] |

Qiang M R, Lang L L, Wang Z L. Do fine-grained components of loess indicate westerlies:Insights from observations of dust storm deposits at Lenghu (Qaidam Basin, China)[J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 2010, 74(10): 1232-1239. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.06.002 |

| [34] |

Sun Y B, Lu H Y, An Z S. Grain size distribution of quartz isolated from Chinese loess/paleosol[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2000, 45(24): 2296-2298. DOI:10.1007/BF02886372 |

| [35] |

孙东怀. 黄土粒度分布中的超细粒组分及其成因[J]. 第四纪研究, 2006, 26(6): 928-936. [ Sun Donghuai. Supper-fine grain size components in Chinese Loess and their palaeoclimatic implication[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2006, 26(6): 928-936. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2006.06.007] |

| [36] |

Sun D H, Chen F H, Bloemendal J, et al. Seasonal variability of modern dust over the Loess Plateau of China[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres, 2003, 108(D21): 4665. |

| [37] |

Lin Y C, Mu G J, Xu L S, et al. The origin of bimodal grain-size distribution for aeolian deposits[J]. Aeolian Research, 2016, 20: 80-88. DOI:10.1016/j.aeolia.2015.12.001 |

| [38] |

Pye K, Tsoar H. The mechanics and geological implications of dust transport and deposition in deserts with particular reference to loess formation and dune sand diagenesis in the Northern Negev, Israel[M]//Glennie K W. Desert sediments: ancient and modern. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 1987, 35(1): 139-156.

|

| [39] |

Vriend M, Prins M A. Calibration of modelled mixing patterns in loess grain-size distributions:An example from the north-eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, China[J]. Sedimentology, 2005, 52(6): 1361-1374. |

| [40] |

Jacobs P M, Mason J A, Hanson P R. Mississippi Valley regional source of loess on the southern Green Bay Lobe land surface, Wisconsin[J]. Quaternary Research, 2011, 75(3): 574-583. DOI:10.1016/j.yqres.2011.02.003 |

| [41] |

史正涛, 董铭. 天山黄土粒度特征及粉尘来源[J]. 云南师范大学学报, 2007, 27(3): 55-57, 64. [ Shi Zhengtao, Dong Ming. Characteristics of loess grain size and source of dust in Tian Shan, China[J]. Journal of Yunnan Normal University, 2007, 27(3): 55-57, 64. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-9793.2007.03.013] |

| [42] |

鄂崇毅, 杨太保, 赖忠平, 等. 中亚则克台黄土剖面记录的末次冰期以来的环境演变[J]. 地球环境学报, 2014, 5(2): 163-172. [ E Chongyi, Yang Taibao, Lai Zhongping, et al. The environmental change records since the last glaciation at Zeketai Loess Section, Central Asia[J]. Journal of Earth Environment, 2014, 5(2): 163-172.] |

| [43] |

Vriend M, Prins M A, Buylaert J P, et al. Contrasting dust supply patterns across the north-western Chinese Loess Plateau during the last glacial-interglacial cycle[J]. Quaternary International, 2011, 240(1/2): 167-180. |

| [44] |

Crouvi O, Amit R, Enzel Y, et al. Sand dunes as a major proximal dust source for late pleistocene loess in the Negev Desert, Israel[J]. Quaternary Research, 2008, 70(2): 275-282. DOI:10.1016/j.yqres.2008.04.011 |

| [45] |

谭亮成, 安芷生, 蔡演军, 等. 4.2ka BP气候事件在中国的降雨表现及其全球联系[J]. 地质论评, 2008, 54(1): 94-104. [ Tan Liangcheng, An Zhisheng, Cai Yanjun, et al. The hydrological exhibition of 4.2ka BP event in China and its global linkages[J]. Geological Review, 2008, 54(1): 94-104. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0371-5736.2008.01.011] |

| [46] |

Wu W X, Liu T S. Possible role of the "Holocene Event 3" on the collapse of Neolithic Cultures around the Central Plain of China[J]. Quaternary International, 2004, 117(1): 153-166. DOI:10.1016/S1040-6182(03)00125-3 |

| [47] |

Shao X H, Wang Y J, Cheng H, et al. Long-term trend and abrupt events of the Holocene Asian monsoon inferred from a stalagmite δ18O record from Shennongjia in Central China[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2006, 51(2): 221-228. DOI:10.1007/s11434-005-0882-6 |

| [48] |

DeMenocal P B. Cultural responses to climate change during the Late Holocene[J]. Science, 2001, 292(5517): 667-673. DOI:10.1126/science.1059827 |

| [49] |

Wei K W, Gasse F. Oxygen isotopes in lacustrine carbonates of West China revisited:Implications for post glacial changes in summer monsoon circulation[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 1999, 18(2): 1315-1334. |

| [50] |

Rhodes T E, Gasse F, Ruifen L, et al. A late pleistocene-holocene lacustrine record from Lake Manas, zunggar (northern Xinjiang, western China)[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1996, 120(1/2): 105-121. |

| [51] |

陶士臣, 安成邦, 陈发虎, 等. 新疆托勒库勒湖孢粉记录的4.2ka BP气候事件[J]. 古生物学报, 2013, 52(2): 234-242. [ Tao Shichen, An Chengbang, Chen Fahu, et al. An abrupt climatic event around 4.2 cal ka BP documented by fossil pollen of Tuolekule Lake in the eastern Xinjiang uyghur autonomous region[J]. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica, 2013, 52(2): 234-242.] |

| [52] |

Zhao J J, An C B, Huang Y S, et al. Contrasting early Holocene temperature variations between monsoonal East Asia and westerly dominated Central Asia[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2017, 178: 14-23. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.10.036 |

| [53] |

刘策, 宋少华, 孔祥辉, 等. 西峰蔡家咀黄土剖面记录的末次盛冰期到全新世最佳期气候变化[J]. 地理科学, 2011, 31(4): 508-512. [ Liu Ce, Song Shaohua, Kong Xianghui, et al. Climatic change from LGM to holocene optimum recorded by loess sequence from Xifeng in Central Loess Plateau[J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2011, 31(4): 508-512.] |

| [54] |

董进国, 吉云松, 钱鹏. 黄土高原洞穴石笋记录的8.2ka B.P.气候突变事件[J]. 第四纪研究, 2013, 33(5): 1034-1036. [ Dong Jinguo, Ji Yunsong, Qian Peng. "8.2ka B.P. Event" of asian monsoon in a stalagmite record from Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2013, 33(5): 1034-1036. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2013.05.20] |

| [55] |

吴敬禄, 沈吉, 王苏民, 等. 新疆艾比湖地区湖泊沉积记录的早全新世气候环境特征[J]. 中国科学(D辑):地球科学, 2003, 33(6): 569-575. [ Wu Jinglu, Shen Ji, Wang Sumin, et al. Characteristics of an Early Holocene climate and environment from lake sediments in Ebinur region, NW China[J]. Science China (Seri. D):Earth Sciences, 2003, 33(6): 569-575.] |

| [56] |

Wünnemann B, Chen F H, Riedel F, et al. Holocene lake deposits of Bosten Lake, southern Xinjiang, China[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48(14): 1429-1432. DOI:10.1360/02wd0270 |

| [57] |

Xue J, Zhong W. Holocene climate variation denoted by Barkol Lake sediments in northeastern Xinjiang and its possible linkage to the high and low latitude climates[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2010, 54(4): 603-614. |

| [58] |

Rasmussen S O, Andersen K K, Svensson A M, et al. A New Greenland ice core chronology for the last glacial termination[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres, 2006, 111(D6): D06102. |

2018, Vol. 36

2018, Vol. 36