扩展功能

文章信息

- 付旭东

- FU XuDong

- 巴丹吉林沙漠石英δ18O值及其物源意义

- Characteristics of Oxygen Isotopic Compositions of Quartz in the Badain Jaran Desert and Its Implications for Sand Provenances

- 沉积学报, 2017, 35(1): 67-74

- ACTA SEDIMENTOLOGICA SINCA, 2017, 35(1): 67-74

- 10.14027/j.cnki.cjxb.2017.01.007

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2016-02-01

- 收修改稿日期: 2016-04-24

沙源是沙漠形成的物质基础[1-2],对其研究不仅有助于认识沙漠的形成演变,而且在防沙治沙工程上也有重要实践意义[3]。巴丹吉林沙漠是地球上沙丘最高大的沙漠[4-5],中国第二大流动沙漠[3]。一直以来,对该沙漠沙源的认识存在不同观点[1, 6-15],可能的物源包括沙漠西北部弱水(额济纳)的河流冲积物和冲积-湖积物、北部的戈壁、残山丘陵和湖相沉积、东南部雅布赖山的基岩风化物、沙漠下伏的红色砂岩和河湖相沉积层。尽管不同学者对哪几类沙源占主导存在分歧,但多数观点都是基于沙漠物源近源性提出的,并未提及沙漠物源的远源性。但Jäkel[10]却认为沙源主要来自弱水下游的冲洪积扇,它们是祁连山地的基岩风化剥蚀后由水流沿黑河搬运至河流末端的产物,蒙古戈壁阿尔泰山也是沙漠的物源地之一。这些观点都是基于野外调查、沉积物粒度或重矿物分析,结合地质地貌资料推论得出的。

近10多年来,随着岩矿化学分析和定年技术的日臻成熟,一些地球化学方法被逐渐引入到中国沙漠的物源研究中[16-19]。石英是沉积物中常见的矿物,其氧同位素组成可示踪物源[20],它在追踪陆地粉尘、黄土高原风成沉积、北太平洋深海沉积和澳大利亚沙漠物源的研究中都有较好的应用[21]。中国沙漠沉积物的石英氧同位素研究也有一些数据报道[21-25],但这些研究多侧重于粉砂粒级或砂粒级的测试分析,对石英氧同位素值与其粒级关系以及它们可能的物源指示意义研究报道尚不多。

以世界上沙丘最高大的巴丹吉林沙漠为研究区,探讨该沙漠沉积物的石英氧同位素与其粒级关系;影响石英氧同位素值的主要因素;结合区域地质资料分析该沙漠可能的物源。

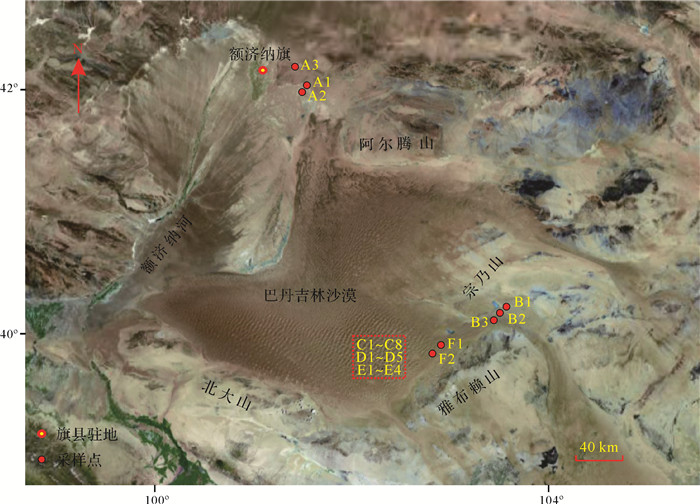

1 研究区与方法 1.1 研究区概况巴丹吉林沙漠位于内蒙古阿拉善荒漠西部,北邻拐子湖,南达合黎山、北大山、龙首山,东至宗乃山、雅布赖山,西抵额济纳河(弱水)东岸的古鲁乃湖(图 1)。面积约5.2×104 km2,是中国第二大沙漠[26]。地势总的变化趋势是南高北低,东高西低[3]。年平均气温9.5℃~10.3℃,1月平均气温-10℃~-20℃,7月平均温度23℃~26℃;年降水量由东南向西北减少,东南部100 mm左右,西北部不足40 mm;年蒸发潜力>2 500 mm[3, 27-28]。终年盛行西北风和西风,年平均风速2.8~4.6 m/s,由东南向西北逐渐加强,年大风日数40~60天[5, 28-29]。区域内地表水系匮乏,仅沙漠西缘的额济纳河有较大的地表径流,其余均为雨季形成的暂时性流水。高大沙山密集分布,约占沙漠总面积的61%,主要集中在沙漠中部,相对高度一般为200~300 m,最高可达500 m左右[5, 30-31]。

|

| 图 1 巴丹吉林沙漠采样点示意图(Google Earth Image) Figure 1 Schematic map of the Badain Jaran Desert and the localities sampled for this study (adapted from Google Earth Image) |

采集巴丹吉林沙漠西北部、东部、东南部高大沙山、丘间地及湖泊、雅布赖山前沙丘的风成沙样品(图 1、表 1)。在自然条件下风干后,用筛析法对A1、B1、C1样品做粒度分析。筛孔直径依次为1 000 μm、500 μm、300 μm、150 μm、90 μm、53 μm、38 μm,将筛析后分级的样品留存备用;静水沉降法提取小于38 μm样品中38~20 μm、 < 20 μm的颗粒。结合研究区已有的沉积物粒度分析资料[14-15, 32]和风沙运动物理规律[33],其余样品用筛析法仅选取125~154 μm和200~250 μm的粒级。

| 样品号 | 经度 | 纬度 | 样品描述 | 采样地点 |

| A1 | 101°35.01′ E | 42°01.01′ N | 湖相沉积物 | 西北部额济纳旗干湖泊 |

| A2 | 101°34.88′ E | 42°00.76′ N | 老风成沙 | 西北部额济纳旗湖相沉积底部 |

| A3 | 101°14.34′ E | 42°20.10′ N | 风成沙 | 西北部额济纳旗平沙地 |

| B1 | 103°36.02′ E | 40°16.01′ N | 湖相沉积物 | 东部树贵湖附近 |

| B2 | 103°35.88′ E | 40°15.76′ N | 沙质沉积物 | 东部树贵湖红层 |

| B3 | 103°21.77′ E | 40°11.45′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东部树贵湖小沙丘顶部 |

| C1 | 102°26.01′ E | 39°45.01′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘底部 |

| C2 | 102°25.73′ E | 39°45.34′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘中部 |

| C3 | 102°25.65′ E | 39°45.21′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘中部100 m |

| C4 | 102°21.07′ E | 39°33.25′ N | 老沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘底部 |

| C5 | 102°21.07′ E | 39°33.25′ N | 新沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘中部50 m |

| C6 | 102°30.15′ E | 39°52.51′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘 |

| C7 | 102°27.85′ E | 39°52.17′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘钙质胶结层上部 |

| C8 | 102°25.22′ E | 39°47.67′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘 |

| D1 | 102°26.53′ E | 39°44.31′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘顶部300 m |

| D2 | 102°26.53′ E | 39°44.31′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘下部170 m |

| D3 | 102°26.53′ E | 39°44.31′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘顶部230 m |

| D4 | 102°26.53′ E | 39°44.31′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘下部80 m |

| D5 | 102°26.53′ E | 39°44.31′ N | 沙丘沙 | 东南部高大沙丘下部40 m |

| E1 | 102°21.05′ E | 39°33.03′ N | 风成沙 | 东南部丘间地1 m钻孔下部 |

| E2 | 102°21.05′ E | 39°33.03′ N | 风成沙 | 东南部丘间地1 m钻孔上部 |

| E3 | 102°21.05′ E | 39°33.03′ N | 湖相沉积物 | 东南部丘间湖泊1.1 m钻孔下部 |

| E4 | 102°21.05′ E | 39°33.03′ N | 风成沙 | 东南部丘间湖泊1.1 m钻孔上部 |

| F1 | 102°58.53′ E | 39°48.38′ N | 沙丘沙 | 雅布赖山前小沙丘顶部 |

| F2 | 102°58.37′ E | 39°47.16′ N | 沙丘沙 | 雅布赖山前小沙丘顶部 |

称取分粒级后的沉积物2 g放入玛瑙研钵,研磨至 < 200目;加入过量H2O2和稀HCl除去沉积物中的有机质、碳酸盐和铁氧化物等,清洗烘干;然后用焦硫酸钠熔融-氟硅酸浸泡法[34-36]将沉积物中的石英颗粒单独分离,经X射线衍射检验石英纯度>95%;用BrF5法提取石英中的氧[37],纯化后的氧被转化为CO2,其氧同位素比值用Finnigan MAT 252质谱仪测定。氧同位素分析结果以δ18O值表示:δ18O=(18O/16O样品-18O/16O标准)/ (18O/16O标准)×1 000,以相对于国际标准(SMOW)报道[38]。质谱仪的测量精度为±0.3‰,样品实验误差为±0.3 ‰,实验所用的标准石英为NBS-28,其δ18O平均值为9.6 ‰。

1.3 数据分析沉积物中石英氧同位素数据的统计分析、均值的非参数检验(Cruskal-Wallis秩和检验),均在SPSS 20.0软件上运行,统计检验显著水平P < 0.05。

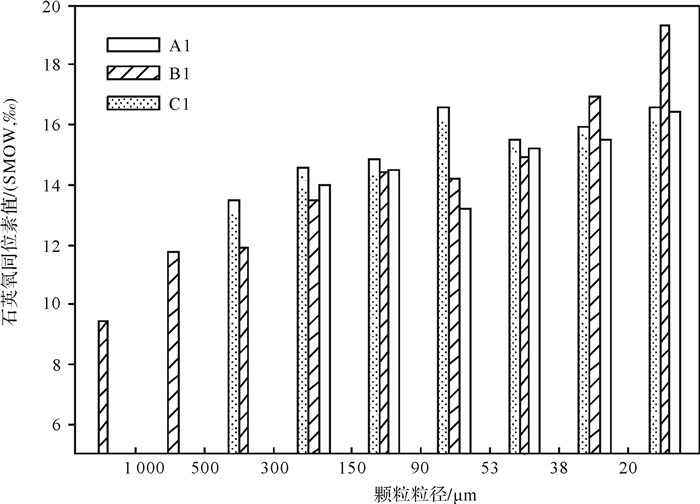

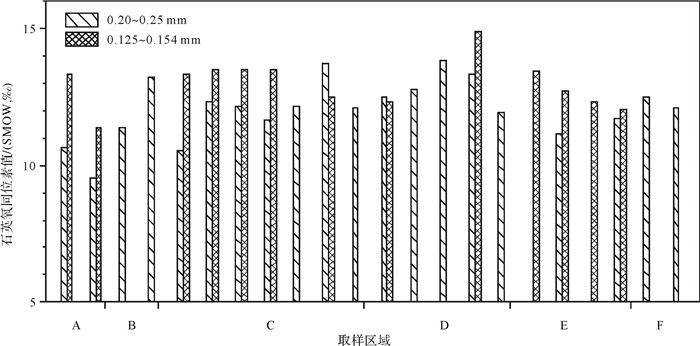

2 结果 2.1 石英δ18O值与粒级关系巴丹吉林沙漠沉积物样品中石英δ18O值与其粒级关系显示:石英δ18O值随粒级的减小有增大趋势(图 2, 3, 4);同一样品中不同粒级石英δ18O值的差别很大,最大相差9.9‰ (图 2);相同粒级的石英δ18O值也有一定的差异(0.4‰~4.3‰),如图 2和图 3。

|

| 图 2 巴丹吉林沙漠沉积物样品中石英δ18O值与粒级关系 Figure 2 Relationship between the δ18O values and grain size for quartz extracted from sediments in the Badain Jaran Desert |

|

| 图 3 巴丹吉林沙漠不同区域细砂粒级沉积物的石英δ18O值与粒级关系 Figure 3 Relationship between the δ18O values and grain size for quartz extracted from fine sand in the Badain Jaran Desert |

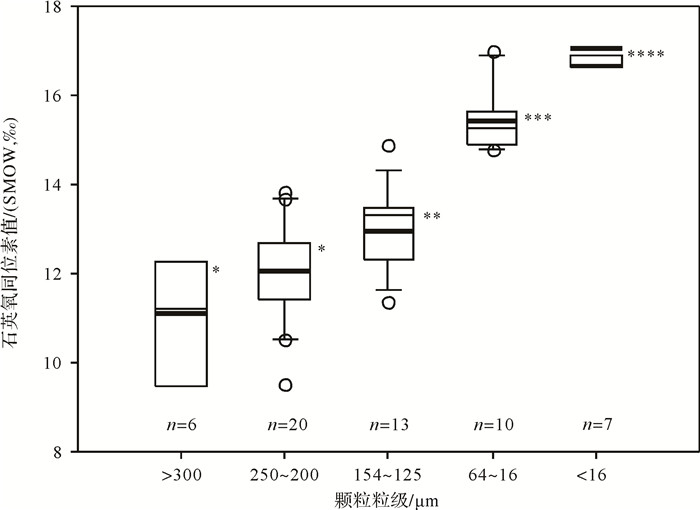

结合巴丹吉林沙漠已有风成沉积物的石英δ18O值数据[25],进行区域内不同粒级的比较。均值的非参数检验(Cruskal-Wallis秩和检验)显示(图 4):>300 μm和250~200 μm粒级的石英δ18O值没有显著差异(P>0.05),但这2个粒级(>300 μm和250~200 μm)与154~125 μm、64~16 μm、 < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值存在显著差异(P < 0.05);154~125 μm、64~16 μm、 < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值也存在显著差异(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 4 巴丹吉林沙漠不同粒级沉积物中石英δ18O值及均值比较 Figure 4 Comparison of the δ18O values in different size fractions for quartz extracted from sediments in the Badain Jaran Desert |

巴丹吉林沙漠沙丘沙和湖相沉积物不同粒级的石英δ18O值测定结果显示(图 2, 3):它们的δ18O值介于9.4‰~19.3‰,均值为13.3‰ (n=55);其中沙丘沙的石英δ18O值介于9.5‰~16.6‰,均值为12.9‰(n=39);湖相沉积物的石英δ18O值介于9.4‰~19.3‰,均值为14.2 ‰ (n=16)。总体上,沙丘沙的石英δ18O值变化范围小,湖相沉积物的石英δ18O值变化范围较大,它们的δ18O值都位于火成岩、砂岩和变质岩的石英δ18O值分布阈值内[39]。

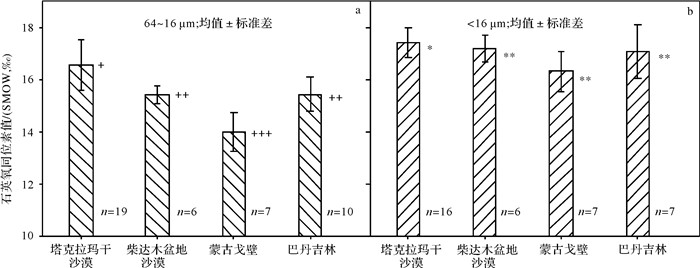

为便于石英δ18O值的区域对比,以 < 16 μm和16~64 μm为界整合已有中国沙漠石英δ18O值数据[21, 25]。均值的非参数检验(Cruskal-Wallis秩和检验)显示(图 5):巴丹吉林沙漠沉积物粗粉砂(16~64 μm)的石英δ18O值与柴达木盆地沙漠粗粉砂的石英δ18O值没有显著性差异(图 5a, P>0.05),但它们与蒙古戈壁、塔克拉玛干沙漠粗粉砂的石英δ18O值存在显著差异(P < 0.001);巴丹吉林沙漠沉积物 < 16 μm组份的石英δ18O值与柴达木盆地沙漠、蒙古戈壁沉积物 < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值没有显著差异(图 5b, P>0.05),但它们与塔克拉玛干沙漠沉积物 < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值存在显著差异(P < 0.01)。总体上,现有的中国沙漠石英δ18O值数据分析显示,塔克拉玛干沙漠粉砂( < 64 μm)粒级的石英δ18O值在中国西部沙漠区内是最大的(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 中国西北沙漠细颗粒沉积物石英δ18O值的均值比较 Figure 5 Comparison of the quartz δ18O values of fine-grained sediments from northwestern deserts in China |

巴丹吉林沙漠沙丘沙和湖相沉积物的石英δ18O值随粒级减小呈现增大趋势(图 2, 3),这与中国北方沙漠/沙地沉积物中石英δ18O值与其粒级呈现的结果一致[23, 25]。黄土高原各地马兰黄土的石英δ18O值随粒级减小也有增大趋势[40-41]。

巴丹吉林沙漠沉积物的石英δ18O值(9.4‰~19.3‰)位于火成岩石英、砂岩和变质岩石英δ18O值的分布值域内[39],同一样品中不同粒级的石英δ18O值存在较大差异,相同粒级的石英δ18O值也有变化(图 2, 3)。主要影响因素有:①区域地质条件的制约。从大的地貌范围看,巴丹吉林沙漠在地势上相对于周围山地是一个低洼的地貌区,周围山地的风化剥蚀产物借助风或水的作用,会将某些粒级的颗粒物质搬运至地势低洼区沉积。这样就造成周围山地岩石的类型组成在区域上决定着沙漠沉积物的石英δ18O值特征。②物质来源复杂但经过风的长期混合。沙漠腹地310 m的钻孔资料表明该沙漠至少在1.1 Ma前已形成[42];多种成因的母岩风化产物,在风力分选下,经过漫长的地质过程,细颗粒物质被搬离开物源地混合,粗颗粒物质则被近距离混合,这可以导致不同成因和来源的石英具有相同粒级,同一样品不同粒级的石英δ18O值存在较大差异。③取样和沉积物中石英单独分离实验过程的影响。由于取样数量有限,沉积物中石英δ18O值与其粒级呈现的关系还需进一步验证,同时还需结合单颗粒石英氧同位素分析技术和年代学手段才能厘清影响石英δ18O值的因素。

3.2 石英δ18O值对巴丹吉林沙漠物源的指示“就地起沙”和“外地来沙”一直是中国沙漠沙源的争议点[19]。在中国沙漠大规模野外调查基础上,结合古地理和地质地貌资料,朱震达等[1]将中国沙漠沙源按成因归为4种类型(河流冲积物、冲积-湖积物、洪积-冲积物和基岩风化的残积、坡积物),具有近源性。此后,各个沙漠沉积物的粒度、重矿物、石英释光灵敏度、元素和同位素地球化学、锆石形态及U-Pb年龄分析也支持该观点[19]。

巴丹吉林沙漠地表沙丘沙中含有的细颗粒组份(粉沙黏土)很低[14-15],但其区域第四纪地层中含有大量的细颗粒物质[32, 42-43]。在巴丹吉林沙漠区域内, < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值与16~64 μm、125~154 μm、200~250 μm、>300 μm粒级的石英δ18O值都存在显著差异,但200~250 μm与>300 μm粒级的石英δ18O值没有显著差异(图 4);区域对比显示,巴丹吉林沙漠 < 16 μm粒级的石英δ18O值与柴达木盆地沙漠、蒙古戈壁风成沉积物 < 16 μm石英δ18O值无显著差异(图 5b),但研究区16~64 μm粒级的石英δ18O值与蒙古戈壁16~64 μm石英δ18O值存在显著差异(图 5a);这似乎暗示巴丹吉林沙漠中细颗粒物质( < 16 μm)可能具有远源性。风沙运动物理学规律[33, 44]和中国黄土多年的研究[45]表明, < 16 μm的颗粒可以在空气中作远距离的搬运,蒙古戈壁位于巴丹吉林沙漠的上风向处,该地区内 < 16 μm的颗粒完全可以顺风搬运至地势相对低洼的巴丹吉林沙漠沉积。这一类型的物源既未在前人有关沙漠物源的研究中提及[19],也不属于朱震达等[1]提出的中国沙漠沙源的4种成因类型。若其他示踪方法能验证,这将是对中国沙漠物源类型的一个重要补充,对中国北方地区防治沙尘暴有一定意义。

巴丹吉林沙漠地表沙丘沙的粒度主要集中于细砂和中砂[14-15],该粒级的石英δ18O值介于9.5‰~14.9‰,均值为12.4‰(n=33,图 4);相同粒级的石英δ18O值存在差异(图 3,4)。石英是沙漠沉积物中主要矿物[1],这表明巴丹吉林沙漠众数粒级颗粒物的母岩是由火成岩、砂岩和变质岩组成的[39],且砂岩和变质岩所占比例应大于火成岩的比例,并经过了风力的长期分选和混合。巴丹吉林沙漠东缘的宗乃山、东南缘的雅布赖山、南缘的合黎山、北大山及龙首山、西缘的马鬃山、北部的萨尔扎山、阿尔腾山等山地出露有大面积各期的火成岩[46],理论上由这些山地风化剥蚀后产生的沉积物石英δ18O值应该位于10.0‰左右[39],这显然与研究区大量实测的沉积物石英δ18O值不吻合(图 2,3);细砂和中砂粒级的颗粒物在风力作用下常以蠕移和跃移方式在地表移动[33, 44];这意味着仅由毗邻巴丹吉林沙漠周围的火成岩山地风化剥蚀产物所提供的近源颗粒物不足以维系沙漠沉积物的物源供给,研究区应有数量巨大的外源沉积物输入,且母岩以砂岩和变质岩占主导,这样才能平衡近源颗粒物的低石英δ18O值。区域地质资料显示[46],巴丹吉林沙漠南部的祁连山区出露有大面积不同时期的变质岩(如板岩、千枚岩、片麻岩等)和砂岩,这些岩石风化剥蚀产生的碎屑沉积物沿着黑河源源不断地输入到沙漠的西北缘(图 1),为巴丹吉林沙漠提供了大量的河湖相沉积物;这些沉积物与沙漠近源沉积物经过风的长期分选和混合后,就能基本吻合目前研究区沉积物的石英δ18O值特征(图 2,3)。Jäkel[10]通过大量野外考察和区域地貌分析也认为祁连山区是巴丹吉林沙漠主要的间接物源地。祁连山区、河西走廊、黑河沿岸以及沙漠周边地区的沉积物粒度分析[47-53]显示:沿祁连山→河流→戈壁滩→沙漠断面,沉积物的中值粒径和分选系数呈现逐渐增大的趋势,偏度逐步向负偏发展;祁连山地的冰水沉积物、冲积-洪积物沿河流向地势低洼的额济纳盆地搬运趋势明显。黑河下游河漫滩沉积物中的碎屑锆石U-Pb年龄[54]也显示这些碎屑沉积物几乎全部源于中、北祁连山地块。

石英氧同位素示踪物源有一定局限性,如存在同值异源现象、石英δ18O值没有年龄标记等问题。在今后的物源研究中,需要增加沙漠区域内的样品数量,采集祁连山区以及沙漠周边山区可能源区的母岩样品,结合其他示踪方法(如Sr-Nd同位素和锆石U-Pb年龄),进行细致的对比研究,继续深入地探讨该问题。

致谢: 感谢杨小平研究员对本项工作给予的支持和帮助,感谢新疆大学资源与环境学院张峰博士提供部分实验数据以及河南大学环境与规划学院王清利副教授建设性的讨论,感谢本文审稿人提出宝贵评审意见和有益建议,在此深表谢忱。| [1] | 朱震达, 吴正, 刘恕, 等. 中国沙漠概论[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1980. [ Zhu Zhenda, Wu Zheng, Liu Shu, et al. An Outline of Chinese Deserts[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1980. ] |

| [2] | Thomas D S G, Wiggs G F S. Aeolian system responses to global change:challenges of scale, process and temporal integration[J]. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2008, 33(9): 1396–1418. DOI: 10.1002/esp.v33:9 |

| [3] | 吴正. 中国沙漠及其治理[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2009. [ Wu Zheng. Sandy Deserts and Its Control in China[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2009. ] |

| [4] | Breed C S, Fryberger S G, Andrews S, et al. Regional studies of sand seas using Landsat (ERTS) imagery[M]//McKee E D. A Study of Global Sand Seas:Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1052. Washington:United States Geological Survey, 1979:305-397. |

| [5] | Dong Zhibao, Qian Guangqiang, Lv Ping, et al. Investigation of the sand sea with the tallest dunes on Earth:China's Badain Jaran sand sea[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2013, 120: 20–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.02.003 |

| [6] | 楼桐茂. 甘肃民勤至巴丹吉林庙间沙漠成因及其改造利用[J]. 治沙研究, 1962 (3): 90–95. [ Lou Tongmao. The formation and utilization of the desert between Minqin and Badain Monastery[J]. Research of Desert Control, 1962(3): 90–95. ] |

| [7] | 于守忠, 李博, 蔡蔚祺, 等. 内蒙古西部戈壁及巴丹吉林沙漠考察[J]. 治沙研究, 1962 (3): 96–108. [ Yu Shouzhong, Li Bo, Cai Weiqi, et al. An expedition to the Gobi and Badain Jaran Desert in the western Inner Mongolia[J]. Research of Desert Control, 1962(3): 96–108. ] |

| [8] | 孙培善, 孙德钦. 内蒙高原西部水文地质初步研究[J]. 治沙研究, 1964 (6): 245–317. [ Sun Peishan, Sun Deqin. The hydrological geology of the western Inner Mongolia[J]. Research of Desert Control, 1964(6): 245–317. ] |

| [9] | 谭见安. 内蒙古阿拉善荒漠的地方类型[J]. 地理集刊, 1964 (8): 1–31. [ Tan Jian'an. The types of deserts in the Alashan Plateau, Inner Mongolia[J]. Geographical Collections, 1964(8): 1–31. ] |

| [10] | Jäkel D. The Badain Jaran desert:its origin and development[J]. Geowissenschaften, 1996, 14(7/8): 272–274. |

| [11] | Yang Xiaoping. Landscape evolution and precipitation changes in the Badain Jaran desert during the last 30000 years[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2000, 45(11): 1042–1047. DOI: 10.1007/BF02884988 |

| [12] | 闫满存, 王光谦, 李保生, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠高大沙山的形成发育研究[J]. 地理学报, 2001, 56 (1): 83–91. [ Yan Mancun, Wang Guangqian, Li Baosheng, et al. Formation and growth of high megadunes in Badain Jaran Desert[J]. Acta Geographica Sinica, 2001, 56(1): 83–91. ] |

| [13] | Mischke S. New evidence for origin of Badain Jaran Desert of Inner Mongolia from granulometry and thermoluminescence dating[J]. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2005, 7(1): 79–97. |

| [14] | 钱广强, 董治宝, 罗万银, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠地表沉积物粒度特征及区域差异[J]. 中国沙漠, 2011, 31 (6): 1357–1364. [ Qian Guangqiang, Dong Zhibao, Luo Wanyin, et al. Grain size characteristics and spatial variation of surface sediments in the Badain Jaran Desert[J]. Journal of Desert Research, 2011, 31(6): 1357–1364. ] |

| [15] | 宁凯, 李卓仑, 王乃昂, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠地表风积砂粒度空间分布及其环境意义[J]. 中国沙漠, 2013, 33 (3): 642–648. [ Ning Kai, Li Zhuolun, Wang Nai'ang, et al. Spatial characteristics of grain size and its environmental implication in the Badain Jaran Desert[J]. Journal of Desert Research, 2013, 33(3): 642–648. ] |

| [16] | Chen Jun, Li Gaojun. Geochemical studies on the source region of Asian dust[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2011, 54(9): 1279–1301. DOI: 10.1007/s11430-011-4269-z |

| [17] | Stevens T, Carter A, Watson T P, et al. Genetic linkage between the Yellow River, the Mu Us desert and the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2013, 78: 355–368. DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.11.032 |

| [18] | Rao Wenbo, Tan Hongbin, Chen Jun, et al. Nd-Sr isotope geochemistry of fine-grained sands in the basin-type deserts, West China:implications for the source mechanism and atmospheric transport[J]. Geomorphology, 2015, 246: 458–471. DOI: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.06.043 |

| [19] | 付旭东, 王岩松. 中国沙漠物源研究:回顾与展望[J]. 沉积学报, 2015, 33 (6): 1063–1073. [ Fu Xudong, Wang Yansong. Provenance studies of Chinese deserts:review and outlook[J]. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica, 2015, 33(6): 1063–1073. ] |

| [20] | Aléon J, Chaussidon M, Marty B, et al. Oxygen isotopes in single micrometer-sized quartz grains:tracing the source of Saharan dust over long-distance atmospheric transport[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2002, 66(19): 3351–3365. DOI: 10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00940-7 |

| [21] | 张峰, 付旭东. 塔克拉玛干沙漠石英氧同位素与粒级关系的研究[J]. 地质论评, 2016, 62 (1): 73–82. [ Zhang Feng, Fu Xudong. Relationships between oxygen isotope compositions of quartz and grain size from dune sands and fluvial-lacustrine sediments in the Taklimakan Desert[J]. Geological Review, 2016, 62(1): 73–82. ] |

| [22] | Ishii T, Isobe I, Mizuno K, et al. Study of the formation processes and sedimentary environment of surface geological features in desertic areas of China, with special reference to the characteristics and origin of eolian sediments[J]. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of Japan, 1995, 46: 651–685. |

| [23] | 付旭东, 杨小平. 中国北方沙漠石英δ18O值的初步测定与分析[J]. 第四纪研究, 2004, 24 (2): 243. [ Fu Xudong, Yang Xiaoping. δ18O in the quartz grains of desert sand in northern China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2004, 24(2): 243. ] |

| [24] | Yang Xiaoping, Zhang Feng, Fu Xudong, et al. Oxygen isotopic compositions of quartz in the sand seas and sandy lands of northern China and their implications for understanding the provenances of aeolian sands[J]. Geomorphology, 2008, 102(2): 278–285. DOI: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.05.007 |

| [25] | Yan Yan, Sun Youbin, Chen Hongyun, et al. Oxygen isotope signatures of quartz from major Asian dust sources:implications for changes in the provenance of Chinese loess[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2014, 139: 399–410. DOI: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.04.043 |

| [26] | 朱金峰, 王乃昂, 陈红宝, 等. 基于遥感的巴丹吉林沙漠范围与面积分析[J]. 地理科学进展, 2010, 29 (9): 1087–1094. [ Zhu Jinfeng, Wang Nai'ang, Chen Hongbao, et al. Study on the boundary and the area of Badain Jaran Desert based on remote sensing imagery[J]. Progress in Geography, 2010, 29(9): 1087–1094. ] |

| [27] | 马宁, 王乃昂, 朱金峰, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠周边地区近50a来气候变化特征[J]. 中国沙漠, 2011, 31 (6): 1541–1547. [ Ma Ning, Wang Nai'ang, Zhu Jinfeng, et al. Climate change around the Badain Jaran Desert in recent 50 years[J]. Journal of Desert Research, 2011, 31(6): 1541–1547. ] |

| [28] | 张克存, 姚正毅, 安志山, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠及其毗邻地区降水特征及风沙环境分析[J]. 中国沙漠, 2012, 32 (6): 1507–1511. [ Zhang Kecun, Yao Zhengyi, An Zhishan, et al. Wind-blown sand environment and precipitation over the Badain Jaran Desert and its adjacent regions[J]. Journal of Desert Research, 2012, 32(6): 1507–1511. ] |

| [29] | Zhang Zhengcai, Dong Zhibao, Li Chunxiao. Wind regime and sand transport in China's Badain Jaran Desert[J]. Aeolian Research, 2015, 17: 1–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.aeolia.2015.01.004 |

| [30] | Dong Zhibao, Qian Guangqiang, Luo Wanyin, et al. Geomorphological hierarchies for complex mega-dunes and their implications for mega-dune evolution in the Badain Jaran Desert[J]. Geomorphology, 2009, 106(3/4): 180–185. |

| [31] | Yang Xiaoping, Scuderi L, Liu Tao, et al. Formation of the highest sand dunes on Earth[J]. Geomorphology, 2011, 135(1/2): 108–116. |

| [32] | 郭峰, 孙东怀, 王飞, 等. 巴丹吉林沙漠地层序列的粒度分布及其组分成因分析[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2014, 34 (1): 165–173. [ Guo Feng, Sun Donghuai, Wang Fei, et al. Grain-size distribution pattern of the depositional sequence in central Badain Jaran Desert and its genetic interpretation[J]. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 2014, 34(1): 165–173. ] |

| [33] | 吴正. 风沙地貌与治沙工程学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2003. [ Wu Zheng. Geomorphology of Wind-Drift Sands and Their Controlled Engineering[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2003. ] |

| [34] | Syers J K, Chapman S L, Jackson M L, et al. Quartz isolation from rocks, sediments and soils for determination of oxygen isotopes composition[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1968, 32(9): 1022–1025. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(68)90067-7 |

| [35] | Sridhar K, Jackson M L, Clayton R N. Quartz oxygen isotopic stability in relation to isolation from sediments and diversity of source[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 1975, 39(6): 1209–1213. DOI: 10.2136/sssaj1975.03615995003900060046x |

| [36] | Jackson M L, Sayin M, Clayton R N. Hexafluorosilicic acid reagent modification for quartz isolation[J]. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 1976, 40(6): 958–960. DOI: 10.2136/sssaj1976.03615995004000060040x |

| [37] | Clayton R N, Mayeda T K. The use of bromine pentafluoride in the extraction of oxygen from oxides and silicates for isotopic analysis[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1963, 27(1): 43–52. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(63)90071-1 |

| [38] | Craig H. Standard for reporting concentrations of deuterium and oxygen-18 in natural waters[J]. Science, 1961, 133(3467): 1833–1834. DOI: 10.1126/science.133.3467.1833 |

| [39] | Savin S M, Epstein S. The oxygen isotopic compositions of coarse grained sedimentary rocks and minerals[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1970, 34(3): 323–329. DOI: 10.1016/0016-7037(70)90109-2 |

| [40] | Gu Z Y, Liu T S, Zheng S H. A preliminary study on quartz oxygen isotope in Chinese Loess and soils[M]//Liu Tungsheng. Aspects of Loess Research. Beijing:China Ocean Press, 1987:291-301. http://www.oalib.com/references/19131075 |

| [41] | Hou Shengshan, Yang Shiling, Sun Jimin, et al. Oxygen isotope compositions of quartz grains (4-16μm) from Chinese eolian deposits and their implications for provenance[J]. Science in China Series D:Earth Sciences, 2003, 46(10): 1003–1011. |

| [42] | Wang Fei, Sun Donghuai, Chen Fahu, et al. Formation and evolution of the Badain Jaran Desert, North China, as revealed by a drill core from the desert centre and by geological survey[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2015, 426: 139–158. DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.03.011 |

| [43] | 蔡厚维. 巴丹吉林地区第四纪地层划分的探讨[J]. 甘肃地质, 1986 (3): 142–153. [ Cai Houwei. The tentative probe of stratigraphical division of Quaternary period in Badanjilin region[J]. Gansu Geology, 1986(3): 142–153. ] |

| [44] | Pye K, Tsoar H. Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes[M]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2009. |

| [45] | 刘东生. 黄土与环境[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1985. [ Liu Tungsheng. Loess and the Environment[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1985. ] |

| [46] | 李廷栋, 耿树方, 范本贤, 等. 中国西部及邻区地质图(1:250万)[M]. 北京: 地质出版社, 2006. [ Li Tingdong, Geng Shufang, Fan Benxian, et al. Geological Map of Western China and Adjacent Areas[M]. Beijing: Geological Publishing House, 2006. ] |

| [47] | 张志高, 张宏亮, 刘青利, 等. 河西走廊不同类型地表沉积物粒度研究[J]. 人民黄河, 2015, 37 (7): 95–100. [ Zhang Zhigao, Zhang Hongliang, Liu Qingli, et al. Particle size analysis of surface sediments and its significance in Hexi Corridor of China[J]. Yellow River, 2015, 37(7): 95–100. ] |

| [48] | 王立强.河西走廊及其毗邻地区地表沉积与亚洲粉尘源区示踪[D].兰州:兰州大学, 2011. [ Wang Liqiang. Surface deposits in the Hexi Corridor and its adjacent areas and implications for provenance of Asian dust[D]. Lanzhou:Lanzhou University, 2011. ] |

| [49] | Nottebaum V, Lehmkuhl F, Stauch G, et al. Regional grain size variations in aeolian sediments along the transition between Tibetan highlands and northwestern Chinese deserts-the influence of geomorphological settings on aeolian transport pathways[J]. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2014, 39(14): 1960–1978. DOI: 10.1002/esp.3590 |

| [50] | Nottebaum V, Stauch G, Hartmann K, et al. Unmixed loess grain size populations along the northern Qilian Shan (China):relationships between geomorphologic, sedimentologic and climatic controls[J]. Quaternary International, 2015, 372: 151–166. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2014.12.071 |

| [51] | Nottebaum V, Lehmkuhl F, Stauch G, et al. Late Quaternary aeolian sand deposition sustained by fluvial reworking and sediment supply in the Hexi Corridor-an example from northern Chinese drylands[J]. Geomorphology, 2015, 250: 113–127. DOI: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.08.014 |

| [52] | Zhang Zhengcai, Dong Zhibao. Grain size characteristics in the Hexi Corridor Desert[J]. Aeolian Research, 2015, 18: 55–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.aeolia.2015.05.006 |

| [53] | Zhang Zhengcai, Dong Zhibao, Li Jiyan, et al. Implications of surface properties for dust emission from gravel deserts (gobis) in the Hexi Corridor[J]. Geoderma, 2016, 268: 69–77. DOI: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.01.011 |

| [54] | 古远.祁连北麓黑河河漫滩沉积物碎屑锆石U-Pb年龄、Hf同位素组成及其地质意义[D].北京:中国地质大学(北京), 2015. [ Gu Yuan. U-Pb dating and Hf isotopic compositions of detrital zircons in the Heihe River's ediments from the northern Qilian Orogen and their geological implications[D]. Beijing:China University of Geosciences (Beijing), 2015. ] |

2017, Vol. 35

2017, Vol. 35