2. 武汉大学中南医院 放射科, 湖北 武汉 430071;

3. 深圳大学总医院 医学影像科, 深圳大学 医学院, 广东 深圳 518055;

4. 武汉大学人民医院 放射科, 湖北 武汉 430060;

5. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. Department of Radiology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430071, China;

3. Department of Medical Imaging, Shenzhen University General Hospital, Medical College of Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518055, China;

4. Department of Radiology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430060, China;

5. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

艾滋病又称获得性免疫缺陷综合征(acquired immune deficiency syndrome,AIDS),是由人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus,HIV)引起的.目前,全球约有3 800万HIV感染者,仅在2019年,就新增170万感染者[1].HIV通过易感染细胞表面的受体进入细胞,以直接或间接的方式破坏人体的免疫系统,其中对CD4+ T细胞的破坏最为严重.当患者CD4+ T细胞数量很低时,细胞免疫几乎完全失去功能,严重增加患者后期由微生物入侵导致罹患恶性肿瘤的可能性,即AIDS[2].联合抗逆转录病毒治疗(combined antiretroviral therapy,cART)是指联合使用三种或三种以上抗逆转录病毒药物治疗艾滋病[3].cART的实施显著降低了艾滋病相关疾病的发病率和死亡率,大大延长了患者的生活年限[4, 5].在cART时期,尽管HIV相关的痴呆发病率显著降低[5-8],但是轻度形式的认知障碍依然常见[5, 7-9].伴有HIV相关的神经认知障碍(HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders,HAND)的HIV感染者比没有HAND的HIV感染者具有更高的死亡风险[7, 8, 10].但这种使患者生活质量受限的疾病的发病机理尚不清楚.

HIV通过周围感染后的白细胞(主要是单核细胞)穿过血脑屏障进入大脑,最早在两周内进入脑脊液[5, 7],在一年甚至几个月内就可以通过磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)技术检测到患者脑结构的变化[11-13].早期的一些神经影像学研究[11, 12, 14-16]报道了HIV/AIDS患者皮层和皮层下脑结构的变化.然而在这些研究中,患者组中既包含接受cART的HIV患者,也包含未治疗的HIV患者,因此cART对HIV患者脑结构的影响还不清楚.一项横断面研究[17]发现未经治疗的HIV患者与经过cART治疗的HIV患者胼胝体、杏仁核、尾状核、丘脑、壳核的体积减少是相近的,对其中12个未经治疗的HIV患者进行纵向研究发现,6个月后这几个脑区体积未发生变化[17].另有研究[16-23]表明,即使接受了cART治疗,HIV/AIDS患者的颞叶、额叶、丘脑、基底神经节、脑干、小脑等脑区仍会遭受损伤.然而也有对接受了cART治疗的HIV患者超过两年的纵向研究[24, 25]发现,HIV患者没有发生灰质体积、皮层厚度和白质完整性的变化,然而这两项研究[24, 25]分别只包含了21个和12个HIV患者,并且没有健康对照.此外,有神经影像学研究显示,未经cART治疗的HIV感染者早期会发生丘脑、小脑等脑区的萎缩和额叶、颞叶等脑区的皮层变薄,但这种变化可以被cART阻止[26].目前评估cART对HIV感染者大脑影响的神经影像学研究还非常有限,并且研究对象也很有限[27].

因此,本研究招募了样本量相对较大的接受cART与未接受cART的HIV患者,以及与人口统计学匹配的健康对照(healthy control,HC),基于三维高分辨脑结构MRI技术,利用基于体素的形态学(voxel-based morphometry,VBM)分析方法对脑灰质体积进行了研究,以实现以下目的:1)研究HIV病毒对未接受cART的HIV患者脑结构的影响;2)探索cART是否可以有效减少HIV患者异常脑结构的发生;3)分析脑结构变化与认知能力和免疫状态的关系.

1 材料和方法 1.1 研究对象收集2011年4月至2014年7月在武汉大学中南医院检查呈血清学HIV阳性、并经国家相关实验室确认的150例HIV患者.经头颅MRI检查、其他相关检查将可疑并发颅内机会性感染或其它病变11例和脑萎缩6例均删除,其余133例常规MRI扫描无异常的患者作为研究对象,其中接受cART的患者组(HIV+/cART+)76例,未接受cART的患者组(HIV+/cART-)57例.HIV患者中,最低CD4+ T细胞计数和图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数分别是1~452 cells/mm3和0~839 cells/mm3,平均病程2.8年(患病时长定义为MRI数据采集时间与临床确诊之间的时间差).患者的平均蒙特利尔认知评估(the Montreal cognitive assessment,MOCA)总得分为23.78.另选取83名年龄、性别匹配的健康志愿者作为HC.本研究获得了武汉大学中南医学伦理委员会的批准.MRI检查前,告知每位受试者本实验的检查目的、内容、过程以及注意事项,征得其同意后,与其签订知情同意书.

1.2 磁共振图像采集所有受试者的磁共振图像均采用西门子3.0 T超导磁共振成像仪(Siemens Magnetom Trio)采集,使用8通道头部矩阵线圈和磁化准备快速采集梯度回波(magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo,MPRAGE)序列,前后连合间线(anterior commissure-posterior commissure,AC-PC)定位,全脑连续扫描.扫描参数如下:重复时间(repetition time,TR)、回波时间(echo time,TE)和反转时间(inversion time,TI)分别为1 900 ms、2.1 ms和900 ms,扫描矩阵为256×256,偏转角为9˚,成像视野(field of view,FOV)为240×240 mm2,层厚为1 mm,层间距为0 mm,扫描160层.

1.3 数据处理数据分析采用基于MATLAB平台的SPM12软件包和CAT12工具箱[28]进行处理.VBM流程如下:(1)将DICOM原始数据转换为NIFTI格式,并进行不均匀场校正;(2)根据已有的先验模板对图像进行组织分割,得到灰质、白质和脑脊液[29];(3)利用李代数微分同胚配准(diffeomorphic anatomical registration through exponentiated Lie algebra,DARTEL)方法将分割后的图像配准到MNI(Montreal neurological institute)空间;(4)利用雅可比行列式对配准后的图像进行调制获得体积信息;(5)调制后的图像采用8 mm高斯核进行空间平滑以提高信噪比,使数据的分布更接近正态分布,并减少空间配准产生的误差.

1.4 统计分析使用SPSS 22.0对数据进行分析.三组之间的年龄差异使用了单因素方差分析检验,性别差异用卡方检验,最低CD4+ T细胞计数、图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数、MOCA总得分等用Mann-Whitney U检验,p < 0.05表示差异有统计学意义.

使用基于体素水平的单因素协方差分析(analysis of covariance,ANCOVA)和T检验评估三组间灰质体积的差异,并把每个被试的年龄、性别和总灰质体积作为协变量.显著性差异的阈值为p < 0.001,激活簇大于200个体素的脑区认为是有统计学差异的脑区.此外,利用Pearson相关分析,探索了灰质体积和临床特征的相关性,p < 0.05被认为有统计学意义.

2 结果 2.1 人口统计信息和临床特征表 1汇总了详细的人口统计信息和临床特征.三组之间的年龄和性别均无显著差异,p值分别为0.64和0.42.与HC相比,HIV患者的认知水平更差(MOCA总得分 < 26).治疗与未治疗的HIV患者组的最低CD4+ T细胞计数没有显著差异(p=0.73),HIV+/cART+组的图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数高于HIV+/cART-组(p < 0.001).

| 表 1 被试的人口统计和临床信息 Table 1 Demographic and clinical information of the participants in this study |

HIV+/cART+、HIV+/cART-和HC组的颅内总体积分别是(1 463±143)、(1 480±136)和(1 472±153)mL,全脑灰质体积分别是(593±62)、(574±59)和(607±73)mL.三组之间的颅内总体积没有统计学差异(F(2, 213)=0.128,p=0.88),三组间的全脑灰质体积的差异具有统计学意义(F(2, 213)=7.7,p=0.01).HIV+/cART-组比HC组与HIV+/cART+组具有更小的全脑灰质体积(p < 0.001,p=0.028),HIV+/cART+组比HC组具有更小的全脑灰质体积,但是这种差异并不显著(图 1).

|

图 1 HIV+/cART+、HIV+/cART-和HC三组之间(a)颅内总体积和(b)全脑灰质体积的差异.三组间的颅内总体积没有显著性差异.与HIV+/cART+和HC相比,HIV+/cART-具有更小的全脑灰质体积,并且HIV+/cART-和HC之间的差异更显著.此外,HIV+/cART+具有比HC更小的全脑灰质体积,但这种差异并不显著.HIV+/cART+:接受抗逆转录病毒治疗的HIV患者;HIV+/cART-:未接受治疗的HIV患者;HC:健康对照;*p < 0.05;**p < 0.001;NS:不显著 Fig. 1 Differences of (a) total intracranial volume and (b) total gray matter volume among HIV+/cART+, HIV+/cART- and HC. There was no significant difference in total intracranial volume among the three groups. Significant lower total gray matter volume in HIV+/cART- were found compared with HIV+/cART+ and HC, and the difference between HIV+/cART- and HC was more significant. In addition, HIV+/cART+ had lower total gray matter volume than HC, but the difference was not significant. HIV+/cART+: HIV positive patients receiving combined antiretroviral therapy; HIV+/cART-: HIV positive patients without treatment; HC: healthy controls; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; NS: no significance |

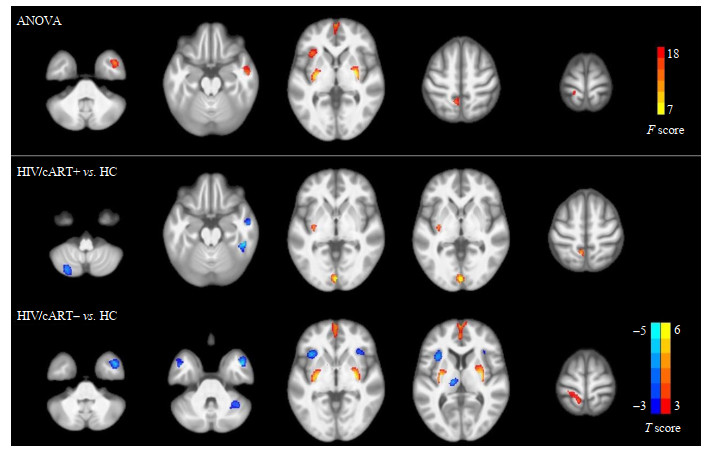

通过人脑磁共振图谱定位差异脑区的解剖学位置[30]及VBM分析发现,三组间灰质体积的差异主要位于右侧颞中回、双侧内侧额回、双侧壳核、左侧脑岛和左侧楔前叶.事后分析显示,与HC相比,HIV+/cART+组在右侧颞中回和左侧小脑后叶具有更小的灰质体积,在双侧舌回、左侧楔前叶具有更大的灰质体积.与HC组相比,HIV+/cART-组在双侧颞中回、双侧脑岛、左侧丘脑等显示较小的灰质体积,在双侧壳核、双侧内侧额回和左侧楔前叶显示较大的灰质体积(图 2、表 2).

|

图 2 HIV+/cART+、HIV+/cART-和HC组之间区域性灰质体积的差异.与HC组相比,HIV+/cART+的灰质体积在右侧颞中回和左侧小脑后叶减少,在双侧舌回和左侧楔前叶增加.此外,与HC相比,HIV/+cART-在双侧颞中回、双侧脑岛和左侧丘脑具有较小的灰质体积,在双侧内侧额回、双侧壳核和左侧楔前叶具有较大的灰质体积.HIV+/cART+,接受抗逆转录病毒治疗的HIV患者;HIV+/cART-,未接受治疗的HIV患者;HC,健康对照 Fig. 2 Regional gray matter volume difference between HIV+/cART+ or HIV+/cART- and HC. Reduced gray matter volume in right middle temporal gyrus and left cerebellum posterior lobe, as well as increased gray matter volume in bilateral lingual gyrus and left precuneus were seen in HIV+/cART+ compared to HC. Additionally, compared with HC, HIV+/cART- exhibited lower gray matter volume mainly in bilateral middle temporal gyrus, bilateral insula and left thalamus, and higher gray matter volume mainly in bilateral medial frontal gyrus, bilateral putamen and left precuneus. HIV+/cART+, HIV positive patients receiving combined antiretroviral therapy; HIV+/cART-, HIV positive patients without treatment; HC, healthy controls |

| 表 2 HIV+/cART+、HIV+/cART-和HC三组之间灰质体积变化的脑区 Table 2 Regions showing gray matter volume differences between HIV+/cART+ or HIV+/cART– and HC |

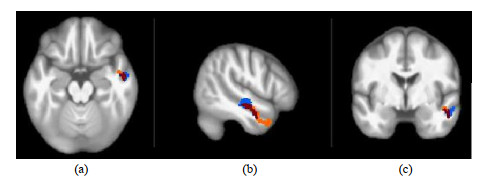

对比各组异常脑区的位置,我们发现灰质体积异常最大的脑区位于右侧颞中回,在未经治疗和接受cART的HIV患者中均发生了灰质体积萎缩.我们把接受cART和未经治疗的HIV患者组与HC组的比较结果放在了同一模板中进行展示.橙色区域表示与HC组相比,HIV+/cART-患者灰质体积减少;蓝色脑区表示与HC组相比,HIV+/cART+患者灰质体积减少;红色表示两组结果重叠的脑区,即HIV+/cART-和HIV+/cART+患者均发生灰质体积萎缩.HIV+/cART-患者右侧颞中回的灰质体积为1.7 mL;HIV+/cART+患者右侧颞中回的萎缩区域明显减少,灰质体积为1.9 mL;HC组右侧颞中回的灰质体积为2.0 mL(图 3).

|

图 3 与健康对照比,接受联合抗逆转录病毒治疗的HIV患者和未接受治疗的HIV患者在右侧颞中回灰质萎缩的对比.橙色区域表示未经治疗的HIV患者灰质萎缩的区域,蓝色表示接受联合抗逆转录病毒治疗的HIV患者发生灰质萎缩的区域,红色表示两组发生灰质萎缩重叠的脑区. (a)横断面,(b)矢状面,(c)冠状面 Fig. 3 Gray matter atrophy in the right middle temporal gyrus was compared between HIV+/cART+ or HIV+/cART- and HC. The orange area represents the gray matter atrophy area in HIV positive patients without treatment, blue indicates the gray matter atrophy area in HIV positive patients receiving combined antiretroviral treatment, and red indicates the brain areas with overlapping gray matter atrophy in the two groups. (a) Transverse view; (b) Sagittal view; (c) Coronal view |

在HIV+/cART+患者组(图 4)中,MOCA总得分与右侧颞中回(r=0.473,p < 0.000 1)、左侧小脑后叶(r=0.386,p=0.002)的灰质体积及全脑灰质体积(r=0.480,p < 0.000 1)显著正相关.治疗时长与图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数(r=0.551,p < 0.000 1)显著相关.显著性差异的脑区的灰质体积以及全脑灰质体积与图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数、最低CD4+ T细胞计数之间没有显著相关性,患病时长与最低CD4+ T细胞计数、图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数、灰质体积变化和MOCA总得分之间没有显著相关性.

|

图 4 接受抗逆转录病毒治疗组中的相关分析.(a)右侧颞中回的灰质体积与MOCA总得分正相关(r=0.473,p < 0.000 1);(b)左侧小脑后叶的灰质体积与MOCA总得分正相关(r=0.386,p=0.002);(c)全脑灰质体积与MOCA总得分正相关(r=0.480,p < 0.000 1);(d) 图像采集时CD4+ T细胞计数与抗逆转录病毒治疗时长正相关(r=0.551,p < 0.000 1) Fig. 4 Correlation analysis in HIV positive patients receiving combined antiretroviral therapy. (a) The gray matter volume of right middle temporal gyrus was positively correlated with total MOAC scores (r=0.473, p < 0.000 1); (b) The gray matter volume of left cerebellum posterior lobe was positively correlated with total MOCA scores (r=0.386, p=0.002); (c) Total gray matter volume was positively correlated with total MOCA scores (r=0.480, p < 0.000 1); (d) There was a positive correlation between the current CD4+ T cell count and the treatment time of combined antiretroviral therapy (r=0.551, p < 0.000 1) |

HIV病毒通过周围感染的白细胞穿过血脑屏障进入大脑,进而影响大脑的结构与功能.以前的研究报道了HIV病毒对脑结构的影响,而HIV病毒对未经治疗的HIV患者脑结构的影响以及cART对HIV患者脑结构的治疗效果还不清楚[15, 31].基于三维高分辨脑结构MRI技术,本研究利用VBM方法探讨cART对HIV患者脑灰质体积的影响.结果显示,未经治疗的HIV患者出现了灰质体积异常,并伴有认知障碍.虽然接受治疗的HIV患者的认知障碍依然存在,但灰质体积异常的区域明显减少.研究结果提示,cART对阻止HIV患者脑结构异常的发生具有明显的效果.

本研究发现HIV+/cART-组的全脑灰质体积显著低于HIV+/cART+组和HC组.虽然HIV+/cART+组与HC组相比具有更小的全脑灰质体积,但是这种差异并不显著.表明cART有效的降低了HIV患者灰质体积的减少.进一步地,VBM发现,HIV+/cART-组的灰质体积的减小主要位于双侧颞中回、双侧脑岛与左侧丘脑.这些发现与现有的一些研究结果相似,目前的很多研究[11, 12, 14, 18, 21, 32-37]表明HIV患者全脑灰质体积和在颞叶、脑岛、丘脑、小脑等脑区灰质体积的减少.本研究发现颞中回是受HIV病毒影响最严重的脑区,也是和认知得分相关性最显著的脑区,结合现有的证据,右侧颞叶的灰质体积和认知得分正相关[36].因此,我们认为颞叶萎缩是导致HIV患者认知能力下降的关键因素.这一发现也支持了现有研究[20]报道的以下观点:颞叶萎缩性变化的存在可能是从神经无症状阶段向HAND过渡的标志.脑岛灰质体积的减少可能与运动缺陷相关[37].先前已经证明,在HIV感染的大鼠[38, 39]和人类中存在严重的小脑萎缩,这可能是众所周知的精神运动技能损害的原因.小脑萎缩可能反映了HIV病毒蛋白的神经毒性作用和被感染的巨噬细胞的毒性产物作用之后神经元的丧失[39].有研究[32]显示伴有认知障碍的未经治疗的艾滋病患者比健康对照在丘脑有更小的灰质体积,而不伴有认知障碍的艾滋病患者与健康对照之间的这种差异不显著.颞叶、脑岛的灰质体积以及全脑灰质体积也受衰老的影响[20, 40].尚不清楚HIV病毒感染的大脑区域特异性的确切原因.HIV病毒蛋白具有神经毒性,灰质体积差异可能反映神经元丢失、树突复杂性降低和突触丢失等[41].HIV病毒会在暴露几天内进入中枢神经系统并引起脑炎[42].在疾病的早期阶段,HIV会诱发中枢神经系统炎性T细胞反应,直接损害少突胶质细胞、神经元和白质[43].在HIV患者的大脑皮层中可以观察到相同的过程,从而诱导神经元凋亡.免疫反应性神经胶质增生和神经元丢失甚至可引起弥漫性脊髓灰质炎[44].这些病理变化可以解释为什么我们的灰质体积研究结果仅显示在双侧颞叶、脑岛和丘脑等多个脑区灰质体积减少.

有趣的是,与HC相比,HIV+/cART-在双侧壳核、双侧内侧额回和左侧楔前叶显示比HC更多的灰质体积.之前有研究[31, 45]报道了壳核、额叶等脑区灰质体积的增大.这些脑区灰质体积增大的确切病因尚不清楚,根据现有的一些研究可以讨论一些可能的机制.结合之前的一些正电子发射断层扫描(positron emission tomography,PET)研究,我们推测这些脑区灰质体积的增加可能是高代谢的结果.患有亚临床神经功能障碍或轻度认知障碍的HIV患者中,基底节神经代谢异常[46-50].随着HIV疾病发展为严重的认知障碍或HIV痴呆状态,观察到基底神经节代谢不足[47-50].也有研究[51]表明基底神经节和额叶皮层代谢物水平和壳核、丘脑体积相关.我们推测可能是上层神经元受损导致功能减弱,下层神经元功能增强导致灰质体积增加.灰质体积增大也可能是炎症的结果.

在HIV+/cART+组中,观察到了CD4+ T细胞数量的恢复,并且与cART的治疗时长呈正相关.这表示随着治疗的进行,HIV患者的免疫功能逐渐恢复.与HC相比,HIV+/cART+患者的右侧颞中回与左侧小脑后叶的灰质体积减小,双侧舌回的灰质体积增加.经过多重比较校正之后,HIV+/cART+和HC的全脑灰质体积没有显著性差异.这与之前的一项研究[24]揭示的接受cART的HIV患者未发生皮层厚度和灰质体积变化的结果是一致的.

HIV的神经发病机制伴随着HIV病毒蛋白引起的脑部炎症[52, 53],体外研究[54]也支持这种观点.即使实施了cART,仍可持续的检测到神经炎症[55].炎症活动可能是HIV患者从无症状向有症状疾病阶段进展的神经学标志[56].cART药物通过抑制血浆和脑脊液中HIV的复制,使患者受损的免疫免疫系统得以重建,从而达到治疗的效果.

目前对于接受cART的HIV患者仍然遭受脑结构损伤主要有两种假设:一种观点是cART药物不能完全穿过血脑屏障,接受治疗的HIV患者脑中仍然持续存在低水平的病毒复制,造成脑结构的异常;另一种是接受治疗的HIV患者的脑结构异常是由治疗前引起的.我们更倾向于第二种假设,因为这与现有的证据以及我们的数据结果更加一致.

比较HIV+/cART+和HIV+/cART-两组患者灰质体积变化的空间位置,发现在HIV+/cART+中发生灰质体积改变的脑区,在HIV+/cART-中同样也能观察到这种变化,尤其是右侧颞中回.结合现有的一些研究[16, 18, 21, 57],我们认为HIV患者的脑结构变化主要是未治疗期间引起的.HIV早期感染后穿过血脑屏障进入大脑,感染并激活中枢神经系统免疫细胞,引发显著的炎症、免疫激活、血脑屏障破坏等,可能造成神经元损伤和脑体积减少[5].很多研究[12, 26, 58]表明HIV感染早期可以引起脑结构的变化,如额叶、颞叶、小脑、丘脑、壳核等.若继续保持未治疗状态,我们推断灰质体积异常会继续.这个观点也被之前一些研究[16, 26]所支持,表示HIV患者感染时间越久(尤其是未治疗持续时间越久),脑结构异常越突出.这也体现了尽早实施cART的重要性,这可能有效的减少结构性脑损伤的发生.

最近有文献[59-61]表明接受治疗的HIV患者的神经心理学表现在三四年内不会发生恶化.在接受cART的HIV患者中,MOCA总得分与右侧颞中回、左侧小脑后叶的灰质体积以及全脑灰质体积显著正相关,这意味着认知功能较差的患者有更小的皮层和皮层下灰质体积[62].这些灰质的变化可能部分解释了HAND的发病率,说明接受cART的HIV患者可能依然伴有认知损伤[16, 18, 21, 63, 64].而这种损伤主要可能是治疗前HIV病毒引起的不可逆损害.与未接受治疗的HIV患者相比,接受治疗的HIV患者的灰质体积异常的脑区显著减少,说明了cART对阻止HIV患者异常脑结构的发生的有效性.最新的研究[24]表明,接受cART的HIV患者的灰质体积、皮质厚度和白质完整性没有纵向差异,表明了cART可以有效的阻止HIV患者脑结构恶化.另一项纵向神经影像学研究[16]表明,接受cART的HIV患者的脑体积异常和皮层变薄随时间的变化与HC相似,也支持了接受cART的HIV患者脑结构的异常是由治疗前引起的这一假设,表明cART可以有效阻止HIV患者脑结构异常的发生.此外,最近有纵向研究[26]表明未治疗的HIV患者早期发生脑体积和皮层厚度变化,但是可以被cART有效的阻止.这也说明了尽早实施cART的重要性.

这项研究有一些局限性.首先,我们的研究是横断面研究,三组受试者的灰质体积随时间的变化还并不清楚,需要进一步的纵向研究来阐明接受cART的HIV患者的脑结构异常是不是持续性的.第二,我们研究中的认知数据只有MOCA总得分,而详细的神经系理学数据可以更好地分析脑结构变化和认知功能的关系.第三,有研究显示抗逆转录病毒药物进入中枢神经系统的有效性会影响HIV患者脑部的治疗效果,我们没有获得相应数据,将来需要进一步的研究来确定不同cART方案是否影响HIV患者的脑结构.最后,将来可以通过静息态功能磁共振成像更深入的探讨cART对HIV患者脑功能的影响[65].

4 结论本研究显示未接受cART的HIV患者在皮层和皮层下区域显示了显著的灰质体积异常,尤其在颞叶和额叶区域,然而接受cART的HIV患者的灰质体积异常明显较少.我们的研究表明cART对阻止HIV患者脑结构异常的发生具有明显的效果,这也强调了尽早实施cART的重要性.

致谢 感谢“国家自然科学基金资助项目(81171315,81571757)”对本研究的支持

利益冲突 无

| [1] | UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update[OL]. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf. 2020. |

| [2] | DALGLEISH A G. The pathogenesis of AIDS: classical and alternative views[J]. J R Coll Physicians Lond, 1992, 26(2): 152-158. |

| [3] | TSIBRIS A M, HIRSCH M S. Antiretroviral therapy in the clinic[J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(11): 5458-5464. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.02524-09. |

| [4] | PALELLA JR F J, DELANEY K M, MOORMAN A C, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV outpatient study investigators[J]. N Engl J Med, 1998, 338(13): 853-860. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. |

| [5] | GONZÁLEZ-SCARANO F, MARTÍN-GARCÍA J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2005, 5(1): 69-81. DOI: 10.1038/nri1527. |

| [6] | BHASKARAN K, MUSSINI C, ANTINORI A, et al. Changes in the incidence and predictors of human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy[J]. Ann Neurol, 2008, 63(2): 213-221. DOI: 10.1002/ana.21225. |

| [7] | ELLERO J, LUBOMSKI M, BREW B. Interventions for neurocognitive dysfunction[J]. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 2017, 14(1): 8-16. DOI: 10.1007/s11904-017-0346-z. |

| [8] | ELBIRT D, MAHLAB-GURI K, BEZALEL-ROSENBERG S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2015, 17(1): 54-59. |

| [9] | HEATON R K, CLIFFORD D B, FRANKLIN JR D R, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study[J]. Neurology, 2010, 75(23): 2087-2096. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. |

| [10] | ELLIS R J, DEUTSCH R, HEATON R K, et al. Neurocognitive impairment is an independent risk factor for death in HIV infection. San diego HIV neurobehavioral research center group[J]. Arch Neurol, 1997, 54(4): 416-424. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160054016. |

| [11] | RAGIN A B, DU H Y, OCHS R, et al. Structural brain alterations can be detected early in HIV infection[J]. Neurology, 2012, 79(24): 2328-2334. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b5b4. |

| [12] | WANG B, LIU Z Y, LIU J J, et al. Gray and white matter alterations in early HIV-infected patients: Combined voxel-based morphometry and tract-based spatial statistics[J]. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2016, 43(6): 1474-1483. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.25100. |

| [13] | RAGIN A B, WU Y, GAO Y, et al. Brain alterations within the first 100 days of HIV infection[J]. Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 2015, 2(1): 12-21. DOI: 10.1002/acn3.136. |

| [14] | LI Y F, LI H J, GAO Q S, et al. Structural gray matter change early in male patients with HIV[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2014, 7(10): 3362-3369. |

| [15] | THOMPSON P M, DUTTON R A, HAYASHI K M, et al. Thinning of the cerebral cortex visualized in HIV/AIDS reflects CD4+T lymphocyte decline[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102(43): 15647-15652. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0502548102. |

| [16] | SANFORD R, FELLOWS L K, ANCES B M, et al. Association of brain structure changes and cognitive function with combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive individuals[J]. JAMA Neurol, 2018, 75(1): 72-79. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3036. |

| [17] | ANCES B M, ORTEGA M, VAIDA F, et al. Independent effects of HIV, aging, and HAART on brain volumetric measures[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2012, 59(5): 469-477. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249db17. |

| [18] | UNDERWOOD J, COLE J H, CAAN M, et al. Gray and white matter abnormalities in treated human immunodeficiency virus disease and their relationship to cognitive function[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2017, 65(3): 422-432. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix301. |

| [19] | TESIC T, BOBAN J, BJELAN M, et al. Basal ganglia shrinkage without remarkable hippocampal atrophy in chronic aviremic HIV-positive patients[J]. J Neurovirol, 2018, 24(4): 478-487. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-018-0635-3. |

| [20] | CLIFFORD K M, SAMBOJU V, COBIGO Y, et al. Progressive brain atrophy despite persistent viral suppression in HIV patients older than 60 years[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2017, 76(3): 289-297. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001489. |

| [21] | VAN ZOEST R A, UNDERWOOD J, DE FRANCESCO D, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in successfully treated HIV infection: associations with disease and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers[J]. J Infect Dis, 2017, 217(1): 69-81. |

| [22] | NIR T M, JAHANSHAD N, CHING C R K, et al. Progressive brain atrophy in chronically infected and treated HIV+individuals[J]. J Neurovirol, 2019, 25(3): 342-353. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-019-00723-4. |

| [23] | CARDENAS V A, MEYERHOFF D J, STUDHOLME C, et al. Evidence for ongoing brain injury in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients treated with antiretroviral therapy[J]. J Neurovirol, 2009, 15(4): 324-333. DOI: 10.1080/13550280902973960. |

| [24] | CORRÊA D G, ZIMMERMANN N, TUKAMOTO G, et al. Longitudinal assessment of subcortical gray matter volume, cortical thickness, and white matter integrity in HIV-positive patients[J]. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2016, 44(5): 1262-1269. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.25263. |

| [25] | CORRÊA D G, ZIMMERMANN N, VENTURA N, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of resting-state connectivity, white matter integrity and cortical thickness in stable HIV infection: Preliminary results[J]. Neuroradiol J, 2017, 30(6): 535-545. DOI: 10.1177/1971400917739273. |

| [26] | SANFORD R, ANCES B M, MEYERHOFF D J, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of brain volume and cortical thickness in treated and untreated primary human immunodeficiency virus infection[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 67(11): 1697-1704. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciy362. |

| [27] | CHANG L, SHUKLA D K. Imaging studies of the HIV-infected brain[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2018, 152: 229-264. |

| [28] | DAHNKE R, YOTTER R A, GASER C. Cortical thickness and central surface estimation[J]. Neuroimage, 2013, 65: 336-348. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.050. |

| [29] | ASHBURNER J, FRISTON K J. Unified segmentation[J]. Neuroimage, 2005, 26(3): 839-851. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. |

| [30] |

CAI W Q, WANG Y J. Advances in construction of human brain atlases from magnetic resonance images[J].

Chinese J Magn Reson, 2020, 37(2): 241-253.

蔡文琴, 王远军. 基于磁共振成像的人脑图谱构建方法研究进展[J]. 波谱学杂志, 2020, 37(2): 241-253. |

| [31] | CASTELO J M, COURTNEY M G, MELROSE R J, et al. Putamen hypertrophy in nondemented patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and cognitive compromise[J]. Arch Neurol, 2007, 64(9): 1275-1280. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.64.9.1275. |

| [32] | HEAPS J M, SITHINAMSUWAN P, PAUL R, et al. Association between brain volumes and HAND in cART-naïve HIV+individuals from Thailand[J]. J Neurovirol, 2015, 21(2): 105-112. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-014-0309-8. |

| [33] | WILSON T W, HEINRICHS-GRAHAM E, BECKER K M, et al. Multimodal neuroimaging evidence of alterations in cortical structure and function in HIV-infected older adults[J]. Hum Brain Mapp, 2015, 36(3): 897-910. DOI: 10.1002/hbm.22674. |

| [34] | CORRÊA D G, ZIMMERMANN N, NETTO T M, et al. Regional cerebral gray matter volume in HIV-positive patients with executive function deficits[J]. J Neuroimaging, 2016, 26(4): 450-457. DOI: 10.1111/jon.12327. |

| [35] | KÜPER M, RABE K, ESSER S, et al. Structural gray and white matter changes in patients with HIV[J]. J Neurol, 2011, 258(6): 1066-1075. DOI: 10.1007/s00415-010-5883-y. |

| [36] | BECKER J T, MARUCA V, KINGSLEY L A, et al. Factors affecting brain structure in men with HIV disease in the post-HAART era[J]. Neuroradiology, 2012, 54(2): 113-121. DOI: 10.1007/s00234-011-0854-2. |

| [37] | ZHOU Y W, LI R L, WANG X X, et al. Motor-related brain abnormalities in HIV-infected patients: a multimodal MRI study[J]. Neuroradiology, 2017, 59(11): 1133-1142. DOI: 10.1007/s00234-017-1912-1. |

| [38] | ABE H, MEHRAEIN P, WEIS S. Degeneration of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and the inferior olivary nuclei in HIV-1-infected brains: a morphometric analysis[J]. Acta Neuropathol, 1996, 92(2): 150-155. DOI: 10.1007/s004010050502. |

| [39] | KLUNDER A D, CHIANG M C, DUTTON R A, et al. Mapping cerebellar degeneration in HIV/AIDS[J]. Neuroreport, 2008, 19(17): 1655-1659. DOI: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328311d374. |

| [40] | TOWGOOD K J, PITKANEN M, KULASEGARAM R, et al. Mapping the brain in younger and older asymptomatic HIV-1 men: frontal volume changes in the absence of other cortical or diffusion tensor abnormalities[J]. Cortex, 2012, 48(2): 230-241. DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.03.006. |

| [41] | WILEY C A, MASLIAH E, MOREY M, et al. Neocortical damage during HIV infection[J]. Ann Neurol, 1991, 29(6): 651-657. DOI: 10.1002/ana.410290613. |

| [42] | VALCOUR V, CHALERMCHAI T, SAILASUTA N, et al. Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection[J]. J Infect Dis, 2012, 206(2): 275-282. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jis326. |

| [43] | GRAY F, SCARAVILLI F, EVERALL I, et al. Neuropathology of early HIV-1 infection[J]. Brain Pathol, 1996, 6(1): 1-15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00775.x. |

| [44] | OZDENER H. Molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 associated neurodegeneration[J]. J Biosci, 2005, 30(3): 391-405. DOI: 10.1007/BF02703676. |

| [45] | SARMA M K, NAGARAJAN R, KELLER M A, et al. Regional brain gray and white matter changes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2014, 4: 29-34. DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.10.012. |

| [46] | HINKIN C H, VAN GORP W G, MANDELKERN M A, et al. Cerebral metabolic change in patients with AIDS: report of a six-month follow-up using positron-emission tomography[J]. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 1995, 7(2): 180-187. DOI: 10.1176/jnp.7.2.180. |

| [47] | ROTTENBERG D A, MOELLER J R, STROTHER S C, et al. The metabolic pathology of the AIDS dementia complex[J]. Ann Neurol, 1987, 22(6): 700-706. DOI: 10.1002/ana.410220605. |

| [48] | ROTTENBERG D A, SIDTIS J J, STROTHER S C, et al. Abnormal cerebral glucose metabolism in HIV-1 seropositive subjects with and without dementia[J]. J Nucl Med, 1996, 37(7): 1133-1141. |

| [49] | VAN GORP W G, MANDELKERN M A, GEE M, et al. Cerebral metabolic dysfunction in AIDS: findings in a sample with and without dementia[J]. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 1992, 4(3): 280-287. DOI: 10.1176/jnp.4.3.280. |

| [50] | VON GIESEN H J, ANTKE C, HEFTER H, et al. Potential time course of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-associated minor motor deficits: electrophysiologic and positron emission tomography findings[J]. Arch Neurol, 2000, 57(11): 1601-1607. |

| [51] | HUA X, BOYLE C P, HAREZLAK J, et al. Disrupted cerebral metabolite levels and lower nadir CD4+counts are linked to brain volume deficits in 210 HIV-infected patients on stable treatment[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2013, 3: 132-142. DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.07.009. |

| [52] | KAUL M, GARDEN G A, LIPTON S A. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia[J]. Nature, 2001, 410(6831): 988-994. DOI: 10.1038/35073667. |

| [53] | MATTSON M P, HAUGHEY N J, Nath A. Cell death in HIV dementia[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2005, 12(Suppl 1): 893-904. |

| [54] | ZHAO M L, KIM M O, MORGELLO S, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, interleukin-1 and caspase-1 in HIV-1 encephalitis[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 2001, 115(1, 2): 182-191. |

| [55] | ANTHONY I C, RAMAGE S N, CARNIE F W, et al. Influence of HAART on HIV-related CNS disease and neuroinflammation[J]. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2005, 64(6): 529-536. DOI: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.529. |

| [56] | CHANG L, LEE P L, YIANNOUTSOS C T, et al. A multicenter in vivo proton-MRS study of HIV-associated dementia and its relationship to age[J]. Neuroimage, 2004, 23(4): 1336-1347. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.067. |

| [57] | SANFORD R, FERNANDEZ CRUZ A L, SCOTT S C, et al. Regionally specific brain volumetric and cortical thickness changes in HIV-infected patients in the HAART era[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2017, 74(5): 563-570. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001294. |

| [58] | WRIGHT P W, PYAKUREL A, VAIDA F F, et al. Putamen volume and its clinical and neurological correlates in primary HIV infection[J]. Aids, 2016, 30(11): 1789-1794. DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001103. |

| [59] | HEATON R K, FRANKLIN D JR R, DEUTSCH R, et al. Neurocognitive change in the era of HIV combination antiretroviral therapy: the longitudinal CHARTER study[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2015, 60(3): 473-480. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciu862. |

| [60] | BROUILLETTE M J, YUEN T, FELLOWS L K, et al. Identifying neurocognitive decline at 36 months among HIV-positive participants in the CHARTER cohort using group-based trajectory analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(5): e0155766. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155766. |

| [61] | SACKTOR N, SKOLASKY R L, SEABERG E, et al. Prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in the multicenter AIDS cohort study[J]. Neurology, 2016, 86(4): 334-340. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002277. |

| [62] | BONNET F, AMIEVA H, MARQUANT F, et al. Cognitive disorders in HIV-infected patients: are they HIV-related?[J]. Aids, 2013, 27(3): 391-400. DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b1019. |

| [63] | COLE J H, UNDERWOOD J, CAAN M W, et al. Increased brain-predicted aging in treated HIV disease[J]. Neurology, 2017, 88(14): 1349-1357. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003790. |

| [64] | COLE J H, CAAN M W A, UNDERWOOD J, et al. No evidence for accelerated aging-related brain pathology in treated human immunodeficiency virus: longitudinal neuroimaging results from the comorbidity in relation to AIDS (COBRA) project[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2018, 66(12): 1899-1909. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix1124. |

| [65] |

YANG L Q, LIN F C, LEI H. Resting state functional connectivity in brain studied by fMRI approach[J].

Chinese J Magn Reson, 2010, 27(3): 326-340.

杨丽琴, 林富春, 雷皓. 静息状态下脑功能连接的磁共振成像研究[J]. 波谱学杂志, 2010, 27(3): 326-340. |

2021, Vol. 38

2021, Vol. 38