文章信息

- 光生物调节在管理抗肿瘤治疗毒性中的研究进展

- Photobiomodulation for Management of Toxicity Induced by Anticancer Therapy: State of the Art

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2023, 50(10): 1004-1009

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2023, 50(10): 1004-1009

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2023.23.0197

- 收稿日期: 2023-03-03

- 修回日期: 2023-06-01

2. 518101 深圳,南方医科大学深圳医院肿瘤科

2. Department of Oncology, Shenzhen Hospital, Nanfang Medical University, Shenzhen 518101, China

光生物调节疗法(photobiomodulation therapy, PBMT)又称弱激光疗法(low-level laser(or light)therapy, LLLT),在2014年北美光治疗协会(NAALT)和世界激光治疗协会(WALT)联合会议上,首次一致认同使用并定义为光,包括可见光、近红外(NIR)、红外(IR)被内源生色团吸收,通过光化学或光物理事件触发非热、非细胞毒性的生物反应,从而导致生理变化,进而产生包括刺激组织再生和伤口愈合、减少炎性反应和疼痛以及免疫调节等积极的治疗结果[1]。

自1967年以来,PBMT在多个医学领域的临床应用数量稳步增长,在癌症治疗及相关毒性方面的应用也越来越多[2-4]。国际癌症支持护理协会/国际口腔肿瘤学协会(MASCC/ISOO)建议,在接受放化疗(chemoradiotherapy, CRT)的头颈部肿瘤患者和接受大剂量细胞减灭药物治疗的干细胞移植患者的口腔黏膜炎治疗中预防性使用PBMT [5]。另外PBMT用于治疗口干症、味觉障碍、放射性皮炎、放疗后纤维化和头颈部肿瘤及乳腺癌相关淋巴水肿等也有报道[6-9]。随着PBMT应用增多,对其生物学机制和临床结果也有了更好的理解,本文就PBMT在癌症治疗中的应用现状进行总结,并为其在肿瘤环境中的安全使用提供思路。

1 光生物调节的生物物理学基础及作用机制低能量激光(LLL)是一种通过非热途径作用于生物系统的特殊激光,波长600~1100 nm,输出功率从5~500 mW的红色光束或近红外激光,可以缓解炎性反应和水肿,从而达到镇痛、促进组织修复的临床疗效。低剂量(2 J/cm2)时,LLLT刺激增殖,而高剂量(16 J/cm2)时,LLLT抑制增殖。研究提示,线粒体数量较多的细胞/组织(肌肉、大脑、心脏、神经)往往比线粒体数量较少的细胞/组织(皮肤、肌腱、软骨)对低剂量的光更有反应,治疗效果差是因为剂量过大而不是剂量不足[10]。另外,在不同的治疗方案中还可以使用不同的激光光源和参数,比如氦氖(632.8 nm)、红宝石(694 nm)和镓铝砷化(805或650 nm)等。

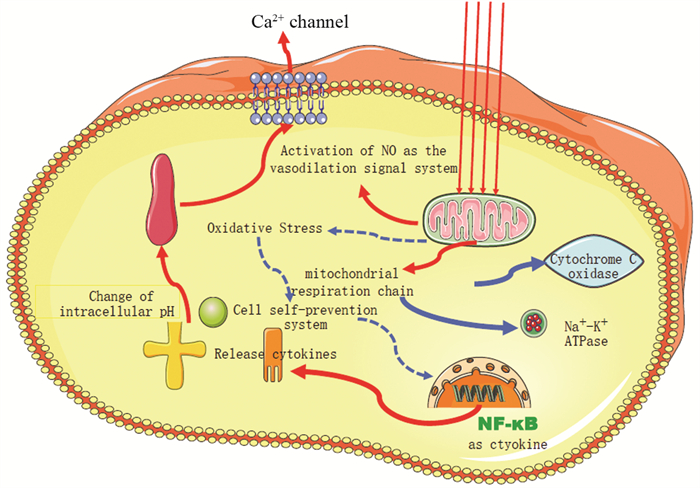

关于PBMT的生物学机制尚未完全阐明,目前的研究表明,PBMT主要作用于线粒体呼吸链中的细胞色素C氧化酶(CCO),通过促进电子传递导致跨膜质子梯度增加,从而驱动三磷酸腺苷(ATP)的产生[11]。此外,红光或近红外光的吸收可能导致活性氧的短暂爆发,使氧化应激的适应性降低。低浓度的活性氧会影响许多细胞过程,如转录因子的激活,刺激成纤维细胞生长因子、炎性细胞因子和趋化因子的基因表达[12],这些转录因子诱导光信号转导和扩增,促进生长因子的产生、细胞的增殖、细胞的流动与黏附性以及增加细胞外基质的沉积。在细胞缺氧或其他应激条件下,线粒体会产生一氧化氮(NO),NO是一种强血管扩张剂,可以增加光照射组织的血液供应。光生物调节(photobiomodulation, PBM)介导的血管调节增加了组织氧合,也允许免疫细胞的流动,有助于促进伤口修复和再生[13],见图 1。

|

| 图 1 光生物调节的潜在分子机制 Figure 1 Potential molecular mechanism of photobiomodulation |

几乎所有接受放疗和放化疗的患者都会有并发症和邻近组织损伤,主要包括:口腔黏膜炎、疼痛、口干、味觉障碍、放射性皮炎、淋巴水肿等,严重影响患者生活质量甚至预后,而这些并发症的发病机制几乎都可由PBM来进行调节。在大多数研究中LLLT/PBM对急性和慢性疾病以及受损组织都证实其安全有效。

2.1 PBMT在放疗相关不良反应中的作用 2.1.1 放射性黏膜炎及疼痛黏膜炎是覆盖在消化道表面黏膜的炎性反应和溃疡,它是由快速分裂的上皮细胞被破坏而引起的。在接受头颈部放疗的头颈肿瘤患者中,放射性黏膜炎的发生率为59%~100%。过量活性氧的形成和核因子κB(NF-κB)的活化是其病理作用的关键因素[14]。PBM除了能够增加ATP合成,减少活性氧和促进炎性细胞因子产生外,它还能刺激成纤维细胞的增殖和迁移能力,胶原蛋白合成和血管生成以利于组织修复[15-16]。目前已有临床研究证明预防性使用PBMT以推迟放射性黏膜炎发生时间或治疗放射性黏膜炎。2011年发表的一篇系统性综述回顾分析了11个随机对照试验中共415例接受化疗或放疗的头颈部肿瘤患者,每天使用16 J/cm2剂量的PBMT可降低口腔黏膜炎的发生率、严重程度和持续时间以及缓解其导致的疼痛症状[17]。另外,一些系统回顾和荟萃分析也显示了预防性使用PBMT可以降低严重的放化疗相关黏膜炎及其疼痛程度[2, 18-19]。然而,既往的研究虽然大多得到了相似的结论,但是最佳的PBMT参数仍未统一,如激光能量密度、激光应用(预防性或治疗性)的理想时间、癌症的类型及治疗方案等。PBMT的疗效取决于细胞的类型和氧化还原状态,以及激光的参数和作用持续时间[20-21]。为了更好的管理PBMT对放射性黏膜炎的治疗,世界光生物调节疗法协会在2022发布了关于预防和治疗放射性口腔黏膜炎的临床实践指南[22],对于预防口腔黏膜炎:若使用口腔内装置,建议选择可见光波长630~680 nm的设备,其功率密度(处理表面辐照度)为10~50 mW/cm2,光子通量650 nm=5.7 p.J/cm2;若使用经皮装置,建议选择波长800~1100 nm,功率密度为30~150 mW/cm2,光子通量810 nm=4.5 p.J/cm2;在肿瘤治疗前30~120 min内进行治疗。对于口腔黏膜炎的治疗,若使用口腔内装置,建议选择可见光波长630~680 nm的设备,光子通量在650 nm=11.4 p.J/cm2;若使用经皮装置,选择波长在800~1100 nm,光子通量在810 nm=9 p.J/cm2;每周重复3~4次,至少15~20次,或直到肿瘤治疗结束后愈合。

2.1.2 放射性皮炎放疗最常见的另一个不良反应是急性放射性皮炎。放射性皮炎的严重程度取决于表皮中活跃增殖的基底细胞存活率。首先,血管通透性增加和血管舒张引起放射性红斑,随后出现炎性反应,导致继发性红斑反应。而当新细胞的更新速度快于旧细胞的脱落速度时,就会形成增厚、干燥、鳞状的皮肤(即干性脱屑)。最后,如果基底层的所有干细胞都被破坏,就会发生湿性脱屑[23]。临床上,PBMT也可作为一种新的预防和治疗工具用于放射性皮炎的管理[7, 24-26]。

一篇系统性综述中分析了9项临床试验,结果提示PBMT可以有效降低严重急性放射性皮炎的发生率,减少疼痛,改善患者的生活质量[24]。临床中,头颈部肿瘤患者在放疗过程中通常会出现2~3级的放射性皮炎[25]。Robijns等进行的两项前瞻性(DERMISHEAD[7])和干预性(TRANSDERM[26])临床研究,均证实PBMT可以降低放疗期间头颈部肿瘤和乳腺癌湿性脱屑的发生率。DERMISHEAD研究中(PBMT参数设定为:波长805~908 nm,能量密度4 J/cm2,放疗期间2次/周,共14次),显示在放疗结束时对照组出现头颈部2~3级放射性皮炎的比例明显高于PBMT组(77.8% vs. 28.6%)。TRANSDERM研究中(PBMT参数设定为:波长808 nm,能量密度4 J/cm2,放疗期间2次/周,共14次),对照组乳腺区皮肤湿性脱屑的发生率明显高于PBMT组(30% vs. 7%),并且乳腺体积 > 800 cc发生湿性脱屑的概率明显增加。DERMISHEAD研究中头颈部肿瘤中重度放射性皮炎的下降率要高于TRANSDERM研究中乳腺癌中重度放射性皮炎的下降率(49% vs. 23%)。这种差异可能是因为头颈部肿瘤患者比乳腺癌患者更容易发生3级放射性皮炎(17% vs. 5%)。目前大多数研究集中在乳腺癌患者使用PBMT上,其次是头颈部肿瘤,但是对于妇科或结肠直肠癌患者,他们容易在生殖器官和肛周区域发生放射性黏膜炎,也可以从PBMT中获益[27]。最近有文献表明[28],PBMT可用于对皮肤进行预处理,这就意味着用可见光和近红外光照射健康的皮肤细胞,可为将来的皮肤损伤做好准备,所以在放疗前对患者进行PBMT预处理可能是预防急性放射性皮炎的一种新方法。

2.1.3 淋巴水肿最近发表的一项荟萃分析,超过五分之一的乳腺癌患者会出现单侧手臂淋巴水肿[29]。Petrek等[30]报道,在诊断乳腺癌20年后的幸存者队列中,49%的患者报告有淋巴水肿。常见症状包括疼痛、严重的功能障碍和心理疾病,并伴有生活质量下降[31]。而PBMT减少了肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α)的产生,增加了白细胞介素(IL)-10的含量,减少了淋巴组织纤维化,刺激了淋巴管生成,增强了淋巴回流,这些结果表明PBMT治疗慢性淋巴水肿是有效的[32]。2006年FDA批准了PBMT作为乳腺癌相关手臂淋巴水肿的治疗方法[33]。一篇纳入7项随机临床试验的系统综述[34]得出结论,PBMT能够改善淋巴水肿相关的手臂肿胀和疼痛症状。2022年发表的一项进行了6个月以上随访的系统综述[32]提示,LLLT(PBMT)对比安慰剂组可以明确减少臂围和臂体积,但是在改善肩部灵活性和疼痛方面则效果不显著。然而,Storz等[35]发表的一项随机安慰剂对照试验,采用了一种紧凑设计的治疗方案,包括治疗8次并且覆盖了腋窝总面积为78.54 cm²的群集激光设备,然而结果并没有显著改善患者的生活质量、疼痛评分及肢体体积。Deng等[36]的一项前瞻性临床试验显示,PBMT颈部对淋巴水肿的严重程度及颈部活动均有统计学意义的改善,提示PBMT治疗头颈部肿瘤患者淋巴水肿的可行性和有效性,但是对于口腔、咽、喉解剖部位的内部软组织肿胀虽然都有减少的趋势,但是无统计学意义的改善。

以上的实验室和临床数据均认为PBMT可能对治疗淋巴水肿有效。因此,建议使用波长400~1100 nm的设备,功率密度(治疗表面辐照度)为10~150 mW/cm2,光子通量810 nm=9 p.J/cm2,每周重复2~3次,持续至少3~4周,临床获益明显[22]。后续还应以这些参数作为基础,设计多中心临床研究进一步优化和验证PBMT的作用。

2.2 PBMT在化疗相关不良反应中的作用 2.2.1 化疗所致的黏膜炎化疗药物所致的黏膜炎涉及细胞和组织损伤,引起慢性或急性炎性反应,释放炎性细胞介质、金属蛋白酶和氧化应激产物,导致组织破坏,从而发生红斑、糜烂和口腔黏膜溃疡。PBMT可以通过炎性介质如环氧合酶-2(COX-2)和TNF-α浓度的降低从而降低口腔黏膜炎严重程度[37-38]。Basso等[39]研究了PMB/LLLT对炎性细胞因子对口腔成纤维细胞的影响,结果提示LLLT可以降低高浓度炎性细胞因子对成纤维细胞功能的负面影响,从而促进伤口愈合。Cauwels等[40]认为,化疗后的免疫功能不全可导致过度的炎性反应,而中性粒细胞和T细胞的近红外光活化效应可能有助于抑制这种反应。在一项Meta分析[41]中,所有纳入的研究结果均表明PBMT可缩短黏膜炎的持续时间,并且在其中大部分研究中PBMT可明显降低黏膜炎的疼痛症状,仅有一项研究对黏膜炎疼痛症状的缓解无统计学意义。

血液系统恶性肿瘤患者比实体瘤患者更容易发生口腔黏膜炎,急性白血病、非霍奇金淋巴瘤和未分化鼻咽癌患者发生口腔黏膜炎的风险最大。Anschau等[42]在系统综述中分析了成年和青少年及儿童两组患者来确定他们使用PBMT后对黏膜炎的获益情况,结果提示,成年患者表现出明显的获益,还黏膜炎的时间缩短。其中两项研究指出,在单纯化疗组和同步放化疗组中平均缩短时间为3.55天和5.70天。然而,在针对儿童的研究中,并没有发现同样的效果。但是其他一些研究结果提示,预防性和治疗性PMBT可减少儿童和年轻癌症患者的黏膜炎和重度黏膜炎发生率,降低口腔黏膜炎的平均严重程度[43-45]。结局不同可能取决于不同的因素,如激光的波长、输出量、剂量、时间和治疗天数等。对于儿科PBMT的治疗方案[22],由于没有充分的证据,目前建议以经皮装置为主,同成人相同方法包括波长、功率、每周治疗次数、PBM治疗总数等,需要后续在此基础之上的临床研究进一步优化及验证。

2.2.2 手足综合征手足综合征是化疗药物和靶向药物导致的常见不良反应,严重的甚至会影响抗肿瘤的治疗,进而影响预后。手足综合征的机制目前尚不明确,部分学者认为其发生与手足血管的炎性反应具有相关性,也可能与COX-2酶的过度表达有关[46]。在一项口腔黏膜炎动物模型中,研究证明LLLT/PBM降低了COX-2的表达,并减少了炎性反应浸润中的中性粒细胞数量[47]。关于PBMT对手足综合征的治疗研究极少,Latifyan等[48]的随机双盲试验观察了PBMT对手足综合征的治疗疗效,采用输出能量为2 J/cm2、强度为500 mU、每周3次的方案,结果发现使用PBMT的患者中49%可明显缓解疼痛,同时并未观察到不良反应,证明PBMT可能是治疗手足综合征的一种有效方法。

2.2.3 周围神经炎化疗所致的周围神经病变(CIPN)也是常见的不良反应之一,目前治疗手段有限。在CIPN期间,可出现疼痛、异位痛、刺痛和手脚麻木等感觉神经异常的表现,甚至可能出现运动和(或)自主功能障碍[49]。诱导CIPN发病的神经病变、轴突病变和(或)髓鞘病变的分子机制目前尚不清楚。周围神经系统的多个作用通路受到影响,包括轴突运输的变化、线粒体功能障碍、氧化应激和表皮内神经纤维的损失。此外,多种离子通道、神经递质及其受体的表达水平都可能发生改变[50]。体内外研究表明PBM可加速和增强轴突生长和再生,抑制神经细胞凋亡[51-52]。目前,只有少数临床试验研究了PBMT在CIPN患者中的治疗情况,研究结果均提示使用PBMT后所有时间点的总神经病变评分均明显降低,症状得到改善[53]。Joy等[54]一项前瞻性、随机、安慰剂对照试验(NEUROLASER试验)评估了PBMT的有效性,结果显示PBMT组的总神经病变评分有降低的趋势,疼痛评分降低,并具有更好的生活质量,说明PBMT对CIPN有潜在的预防作用。

3 PBMT尚未明确的问题目前大量研究已证明PBMT在肿瘤放化疗所致相关不良反应治疗中的安全及有效性,但是在使用中均指出了避免激光直接应用于肿瘤部位,因为PBMT对肿瘤的影响并未得到充分研究。一项体外研究发现PBMT可能触发肿瘤细胞下游的致癌信号通路,增加局部口腔恶性肿瘤的风险[55]。但也有文章报告了矛盾的结果,激光可以直接损伤肿瘤,增强抗肿瘤效应,并可以刺激宿主免疫系统。此外,有两项临床试验显示,接受PBMT的肿瘤患者生存期增加[56-57],所以将PBMT与抗肿瘤治疗相结合存在一定的可能性。另外,由于使用PBMT的目的(治疗/预防)不同,所制定的PBMT设备和剂量学参数仍需研究者不断探索,进行标准化,如波长、能量、功率密度、脉冲结构、治疗时机、治疗间隔等。

利益冲突声明:

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献:

李莹:文献整理,论文设计与撰写

胡德胜:参与选题及设计,对论文提出建议

谭文勇:论文设计及修改,基金支持

| [1] |

Anders JJ, Lanzafame RJ, Arany PR. Low-level light/laser therapy versus photobiomodulation therapy[J]. Photomed Laser Surg, 2015, 33(4): 183-184. DOI:10.1089/pho.2015.9848 |

| [2] |

Oberoi S, Zamperlini-Netto G, Beyene J, et al. Effect of prophylactic low level laser therapy on oral mucositis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(9): e107418. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0107418 |

| [3] |

Hodgson BD, Margolis DM, Salzman DE, et al. Amelioration of oral mucositis pain by NASA near-infrared light-emitting diodes in bone marrow transplant patients[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2012, 20(7): 1405-1415. DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1223-8 |

| [4] |

Baxter GD, Liu L, Petrich S, et al. Low level laser therapy (photobiomodulation therapy) for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 833. DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3852-x |

| [5] |

Zadik Y, Arany PR, Fregnani ER, et al. Systematic review of photobiomodulation for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients and clinical practice guidelines[J]. Supportive Care Cancer, 2019, 27(10): 3969-3983. DOI:10.1007/s00520-019-04890-2 |

| [6] |

Louzeiro GC, Teixeira DDS, Cherubini K, et al. Does laser photobiomodulation prevent hyposalivation in patients undergoing head and neck radiotherapy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2020, 156: 103115. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103115 |

| [7] |

Robijns J, Lodewijckx J, Claes S, et al. Photobiomodulation therapy for the prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in head and neck cancer patients (DERMISHEAD trial)[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2021, 158: 268-275. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2021.03.002 |

| [8] |

Heiskanen V, Zadik Y, Elad S. Photobiomodulation therapy for cancer treatment-related salivary gland dysfunction: a systematic review[J]. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg, 2020, 38(6): 340-347. |

| [9] |

Bensadoun RJ. Photobiomodulation or low-level laser therapy in the management of cancer therapy-induced mucositis, dermatitis and lymphedema[J]. Curr Opin Oncol, 2018, 30(4): 226-232. DOI:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000452 |

| [10] |

Zein R, Selting W, Hamblin MR. Review of light parameters and photobiomodulation efficacy: dive into complexity[J]. J Biomed Opt, 2018, 23(12): 1-17. |

| [11] |

Antunes F, Boveris A, Cadenas E. On the mechanism and biology of cytochrome oxidase inhibition by nitric oxide[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004, 101(48): 16774-16779. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0405368101 |

| [12] |

Yadav A, Gupta A. Noninvasive red and near-infrared wavelength-induced photobiomodulation: promoting impaired cutaneous wound healing YADAV A, GUPTA A. Noninvasive red and near-infrared[J]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, 2017, 33(1): 4-13. DOI:10.1111/phpp.12282 |

| [13] |

Lohr NL, Keszler A, Pratt P, et al. Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: potential role in cardioprotection[J]. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2009, 47(2): 256-263. DOI:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.009 |

| [14] |

Gouvêa de Lima A, Villar RC, de Castro G Jr, et al. Oral mucositis prevention by low-level laser therapy in head-and-neck cancer patients undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a phase Ⅲrandomized study[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012, 82(1): 270-275. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.012 |

| [15] |

Basso FG, Pansani TN, Turrioni AP, et al. In vitro wound healing improvement by low-level laser therapy application in cultured gingival fibroblasts[J]. Int J Dent, 2012, 2012: 719452. |

| [16] |

Moshkovska T, Mayberry J. It is time to test low level laser therapy in Great Britain[J]. Postgrad Med J, 2005, 81(957): 436-441. DOI:10.1136/pgmj.2004.027755 |

| [17] |

Bjordal JM, Bensadoun RJ, Tunèr J, et al. A systematic review with metaanalysis of the effect of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in cancer therapyinduced oral mucositis[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2011, 19(8): 1069-1077. DOI:10.1007/s00520-011-1202-0 |

| [18] |

Carvalho PA, Jaguar GC, Pellizzon AC, et al. Evaluation of low-level laser therapy in the prevention and treatment of radiationinduced mucositis: a double-blind randomized study in head and neck cancer patients[J]. Oral Oncol, 2011, 47(12): 1176-1181. DOI:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.021 |

| [19] |

Marín-Conde F, Castellanos-Cosano L, Pachón-Ibañez J, et al. Photobiomodulation with low-level laser therapy reduces oral mucositis caused by head and neck radio-chemotherapy: prospective randomized controlled trial[J]. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2019, 48(7): 917-923. DOI:10.1016/j.ijom.2018.12.006 |

| [20] |

Elad S, Arany P, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Photobiomodulation therapy in the management of oral mucositis: search for the optimal clinical treatment parameters[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2018, 26(10): 3319-3321. DOI:10.1007/s00520-018-4262-6 |

| [21] |

Huang YY, Sharma SK, Carroll J, et al. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy - an update[J]. Dose Response, 2011, 9(4): 602-618. |

| [22] |

Robijns J, Nair RG, Lodewijckx J, et al. Photobiomodulation therapy in management of cancer therapy-induced side effects: WALT position paper 2022[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 927685. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2022.927685 |

| [23] |

Hegedus F, Mathew LM, Schwartz RA. Radiation dermatitis: an overview[J]. Int J Dermatol, 2017, 56(9): 909-914. DOI:10.1111/ijd.13371 |

| [24] |

Robijns J, Lodewijckx J, Bensadoun RJ, et al. A narrative review on the use of photobiomodulation therapy for the prevention and management of acute radiodermatitis: proposed mechanisms, current clinical outcomes, and preliminary guidance for clinical studies[J]. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg, 2020, 38(6): 332-339. |

| [25] |

Iacovelli NA, Galaverni M, Cavallo A, et al. Prevention and treatment of radiation-induced acute dermatitis in head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review[J]. Future Oncol, 2018, 14(3): 291-305. DOI:10.2217/fon-2017-0359 |

| [26] |

Robijns J, Censabella S, Claes S, et al. Biophysical skin measurements to evaluate the effectiveness of photobiomodulation therapy in the prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2019, 27(4): 1245-1254. DOI:10.1007/s00520-018-4487-4 |

| [27] |

Censabella S, Claes S, Bever LV, et al. Vaginal mucositis in patients receiving chemoradiation for gyneocological cancer: a frequent but neglected side effect of cancer and cancer therapies[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2018, 26: S39-S364. DOI:10.1007/s00520-018-4193-2 |

| [28] |

Barolet D. Photobiomodulation in dermatology: harnessing light from visible to near infrared[J]. Med Res Arch, 2018, 6. |

| [29] |

DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2013, 14(6): 500-515. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7 |

| [30] |

Petrek JA, Senie RT, Peters M, et al. Lymphedema in a cohort of breast carcinoma survivors 20 years after diagnosis[J]. Cancer, 2001, 92(6): 1368-1377. DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1368::AID-CNCR1459>3.0.CO;2-9 |

| [31] |

Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, et al. Arm edema in breast cancer patients[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2001, 93(2): 96-111. DOI:10.1093/jnci/93.2.96 |

| [32] |

Mahmood D, Ahmad A, Sharif F, et al. Clinical application of low-level laser therapy (Photo-biomodulation therapy) in the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review[J]. BMC Cancer, 2022, 22(1): 937. DOI:10.1186/s12885-022-10021-8 |

| [33] |

Robijns J, Censabella S, Bulens P, et al. The use of low-level light therapy in supportive care for patients with breast cancer: review of the literature[J]. Lasers Med Sci, 2017, 32(1): 229-242. DOI:10.1007/s10103-016-2056-y |

| [34] |

Smoot B, Chiavola-Larson L, Lee J, et al. Effect of low-level laser therapy on pain and swelling in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Cancer Surviv, 2015, 9(2): 287-304. DOI:10.1007/s11764-014-0411-1 |

| [35] |

Storz MA, Gronwald B, Gottschling S, et al. Photobiomodulation therapy in breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized placebo-controlled trial[J]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, 2017, 33(1): 32-40. DOI:10.1111/phpp.12284 |

| [36] |

Deng J, Lukens JN, Swisher-McClure S, et al. Photobiomodulation Therapy in Head and Neck Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Pilot Feasibility Study[J]. Integr Cancer Ther, 2021, 20: 15347354211037938. |

| [37] |

Lopes NN, Plaper H, Chavantes MC, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in hamsters: evaluation of two low-intensity laser protocols[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2009, 17(11): 1409-1415. DOI:10.1007/s00520-009-0603-9 |

| [38] |

Campos L, Cruz ÉP, Pereira FS, et al. Comparative study among three diferente phototherapy protocols to treat chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in hamsters[J]. J Biophotonics, 2016, 9(11-12): 1236-1245. DOI:10.1002/jbio.201600014 |

| [39] |

Basso FG, Soares DG, Pansani TN, et al. Proliferation, migration and experssion of oral-mucosalhealing- related genes by oral fibroblasts receiving low-level laser therapy after inflammatory cytokines challenge[J]. Lasers Surg Med, 2016, 48(10): 1006-1014. DOI:10.1002/lsm.22553 |

| [40] |

Cauwels RGEC, Martens LC. Low level laser therapy in oral mucositis: a pilot study[J]. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent, 2011, 12(2): 116-121. |

| [41] |

Al-Rudayni AHM, Gopinath D, Maharajan MK, et al. Efficacy of Oral Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucositis Associated with Cancer Chemotherapy: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis[J]. Curr Oncol, 2021, 28(4): 2852-2867. DOI:10.3390/curroncol28040250 |

| [42] |

Anschau F, Webster J, Capra MEZ, et al. Efficacy of low-level laser for treatment of cancer oral mucositis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lasers Med Sci, 2019, 34(6): 1053-1062. DOI:10.1007/s10103-019-02722-7 |

| [43] |

He M, Zhang B, Shen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) on chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in pediatric and young patients[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2018, 177(1): 7-17. DOI:10.1007/s00431-017-3043-4 |

| [44] |

Oberoi S, Zamperlini-Netto G, Beyene J, et al. Effect of prophylactic low level laser therapy on oral mucositis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e107418-e107428. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0107418 |

| [45] |

Migliorati C, Hewson I, Lalla RV, et al. Systematic review of laser and other light therapy for the management of oral mucositis in cancer patients[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2013, 21(1): 333-341. DOI:10.1007/s00520-012-1605-6 |

| [46] |

Lin EH, Curley SA, Crane CC, et al. Retrospective study of capecit abine and celecoxib in metastatic colorectal cancer: potential benefits and COX-2 as the common mediator in pain, toxicities and survival[J]. Clin Oncol, 2006, 29(3): 232-239. |

| [47] |

Epstein JB, Thariat J, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy: from cancer treatment to survivorship[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2012, 62(6): 400-422. DOI:10.3322/caac.21157 |

| [48] |

Latifyan S, Genot MT, Fernez B, et al. Use of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) or photobiomodulation (PBM) for the management of the hand-foot syndrome (HSF) or palmo-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPED) associated with cancer therapy[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2020, 28(7): 3287-3290. DOI:10.1007/s00520-019-05099-z |

| [49] |

Hou S, Huh B, Kim HK, et al. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: systematic review and recommendations[J]. Pain Physician, 2018, 21(6): 571-592. |

| [50] |

Han Y, Smith MT. Pathobiology of cancer chemotherapyinduced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN)[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2013, 4: 156. |

| [51] |

Cho H, Jeon HJ, Park S, et al. Neurite growth of trigeminal ganglion neurons in vitro with near-infrared light irradiation[J]. J Photochem Photobiol B, 2020, 210: 111959. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111959 |

| [52] |

Anders JJ, Moges H, Wu X, et al. In vitro and in vivo optimization of infrared laser treatment for injured peripheral nerves[J]. Lasers Surg Med, 2014, 46(1): 34-45. DOI:10.1002/lsm.22212 |

| [53] |

Argenta PA, Ballman KV, Geller MA, et al. The effect of photobiomodulation on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2017, 144(1): 159-166. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.013 |

| [54] |

Joy L, Jolien R, Marithé C, et al. The use of photobiomodulation therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial (NEUROLASER trial)[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2022, 30(6): 5509-5517. DOI:10.1007/s00520-022-06975-x |

| [55] |

Basso FG, Oliveira CF, Kurachi C, et al. Biostimulatory Effect of low-level laser therapy on Keratinocytes in Vitro[J]. Lasers Med Sci, 2013, 28(2): 367-374. DOI:10.1007/s10103-012-1057-8 |

| [56] |

Antunes HS, Herchenhorn D, Small IA, et al. Long-term survival of a randomized phase Ⅲ trial of head and neck cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiation therapy with or without low-level laser therapy (LLLT) to prevent oral mucositis[J]. Oral Oncol, 2017, 71: 11-15. DOI:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.05.018 |

| [57] |

Santana-Blank LA, Rodríguez-Santana E, Vargas F, et al. PhaseⅠ trial of an infrared pulsed laser device in patients with advanced neoplasias[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2002, 8(10): 3082-3091. |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50