文章信息

- 乳腺癌患者原发性肺癌发生风险的系统评价和Meta分析

- Risk of Primary Lung Cancer in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2021, 48(7): 733-737

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2021, 48(7): 733-737

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2021.20.1430

- 收稿日期: 2020-12-09

- 修回日期: 2021-01-26

2. 050011 石家庄,河北医科大学第四医院科研中心

2. Center of Scientific Research, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang 050011, China

乳腺癌是全球女性最常见的恶性肿瘤[1],严重威胁女性的身心健康。虽然乳腺癌的发病率在不断增加,但随着对乳腺癌逐步深入的认识以及诊疗技术的不断进步,死亡率显著下降[2]。由于存活率和平均预期寿命的提高,乳腺癌患者发生第二原发性恶性肿瘤的风险尤其令人关注。

肺癌是全世界癌症患者死亡的主要原因[3],在女性肿瘤发病中仅次于乳腺癌。以往的队列研究评估了乳腺癌患者发生肺癌的风险,但乳腺癌和肺癌之间是否存在相关性仍不能确定。Okamoto等[4]通过对854名乳腺癌患者进行随访发现,肺癌的发病率是普通人群的2.42倍。Burt等[5]在1973—2008年期间SEER数据库中374 993名乳腺癌患者的队列中发现,乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌的风险并未增加。由于小规模的个体队列研究不足以确定乳腺癌患者中肺癌的发病率,因此需要一项全面的研究来澄清这一人群发生肺癌的风险,并评估肺癌发生的风险是否与确诊年龄相关。因此,我们进行了本项系统评价和Meta分析,更加全面地分析原发性肺癌在乳腺癌患者中的发病情况。

1 资料与方法 1.1 检索策略在Medline、Scopus以及Embase数据库中进行了系统检索,以查找截至2020年5月2日发表的相关文章。我们选择以下与“多原发癌”、“第二原发癌”、“乳腺癌”、“肺癌”以及“流行病学”相关的MeSH术语:Neoplasms/Multiple Primary, Neoplasms/Second Primary,Breast Neoplasms,Lung Neoplasms and epidemiology。在不同的数据库中还使用并组合了许多关键词(“Population-based”和“Risk”)。

1.2 文献纳入与排除标准纳入标准:(1)有关原发浸润性乳腺癌女性发生原发性肺癌风险的原创文章;(2)文章类型:回顾性研究;(3)基于人群和队列的研究或癌症登记的研究;(4)人群特征:成年女性;(5)研究包含标准化发病率(standardized incidence ratio, SIR)及其95%CI;(6)英文文献。排除标准:(1)会议摘要、案例报告和综述;(2)非队列研究;(3)重复报道或数据描述不清楚的研究。

1.3 数据提取两位作者根据纳入标准对潜在合格文章的标题和摘要进行独立筛选。保留两位作者初步筛选的重复文章,存在分歧或不确定的文章通过协商解决。在标题和摘要筛选的基础上,满足纳入标准的文章进行全文分析,以排除不包括肺癌患者以及未报告SIR的研究。

使用标准化数据提取表从所有符合纳入条件的研究中提取以下数据:第一作者、发表年份、国家、研究时间、平均随访时间、数据来源、原发性乳腺癌病例和第二原发性肺癌病例的数量(观察和预期)、乳腺癌患者第二原发肺癌的SIR和95%CI。

1.4 统计学方法根据系统评价和Meta分析(PRISMA)指南的首选报告项目[6]对本文进行了系统综述。统计学分析均采用Stata15.5软件进行。纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NOS)用于评估纳入研究的偏倚风险,评分在6分或更高的研究被认为是高质量的。在Meta分析中,对乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌的SIR及其95%CI进行合并。采用Cochran‘s Q统计量进行异质性检验,P < 0.10表示有异质性,并用I2统计量表示由于异质性引起的研究总变异性的百分比(I2: < 25%,低度异质性;I2: 25%~50%,中度异质性;I2: > 50%,高度异质性)[7]。如果研究出现显著的异质性,选择随机效应模型进行分析,否则选择固定效应模型。此外,通过Begg’s及Egger’s检验量化发表偏倚[8],当P≥0.05时表明差异无统计学意义,即认为无明显的发表性偏倚。

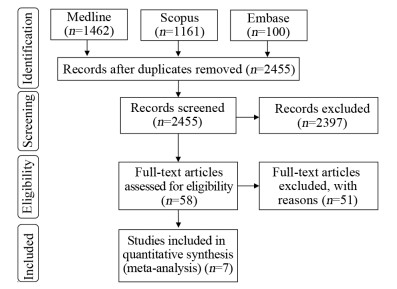

2 结果 2.1 文献检索检索发现2 723篇相关文献,其中2 397篇文献经过标题和摘要的初步筛选后被排除,对58篇文献全文进行了资格评估以及排除了同一人群中的研究。通过严格地筛选后共7篇文献[9-15]符合纳入标准,将7个不同国家/地区远超过15万名乳腺癌患者纳入Meta分析。文献检索流程图见图 1。

|

| 图 1 PRISMA声明文献筛选流程 Figure 1 Flow chart of studies selection according to PRISMA Statement |

采用NOS对纳入研究进行质量评价,所有纳入研究的NOS评分均≥7分,质量均较高。纳入研究的基本特征见表 1。

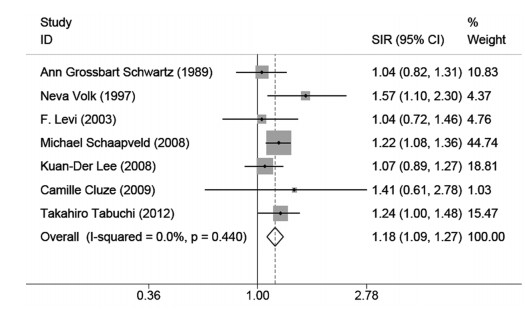

对纳入的7篇研究进行异质性检验,各研究之间不存在异质性(I2=0, P=0.44),采用固定效应模型分析乳腺癌患者发生肺癌的风险。结果表明,女性乳腺癌患者发生肺癌的风险是一般人群的1.18倍(SIR: 1.18, 95%CI: 1.09~1.27),见图 2。

|

| 图 2 乳腺癌患者发生肺癌的标准化发病率 Figure 2 Standardized incidence ratios of lung cancer in breast cancer patients |

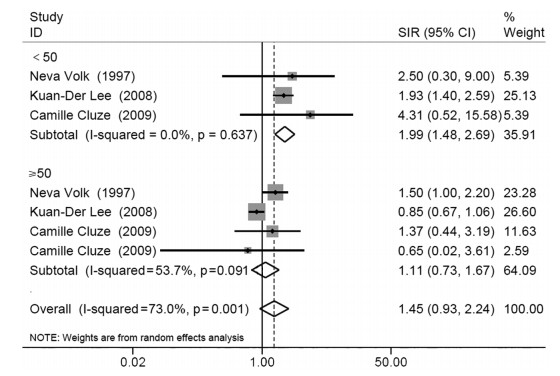

由于确诊年龄分组不同或缺乏数据,纳入的7篇研究中只有3项研究被纳入亚组分析。3篇研究之间存在异质性(I2=73%, P=0.001),故采用随机效应模型进行分析。针对确诊年龄进行的亚组分析显示,与确诊年龄≥50岁的女性乳腺癌患者(SIR: 1.11, 95%CI: 0.73~1.67)相比,乳腺癌确诊年龄 < 50岁的女性发生肺癌的风险显著升高(SIR: 1.99, 95%CI: 1.48~2.69),见图 3。

|

| 图 3 按确诊年龄分类的乳腺癌患者发生肺癌的标准化发病率 Figure 3 Standardized incidence ratios of lung cancer in breast cancer patients classified by age at diagnosis |

对每组进行敏感度分析,以评估该Meta分析的稳定性。当删除任何一项研究时,相关的合并SIR并未发生根本改变,表明了Meta分析的稳定性。Begg’s检验和Egger’s检验均表明在Meta分析中不存在发表偏倚(Begg’s检验,P=0.764; Egger’s检验,P=0.748)。

3 讨论随着乳腺癌诊疗技术的不断进步和对乳腺癌幸存者更密切的医学随访,乳腺癌幸存者发生第二原发恶性肿瘤的风险也在不断增加。Ricceri等[16]通过对10 045例浸润性乳腺癌患者进行11年的随访发现:乳腺癌女性患者患第二原发性恶性肿瘤的风险增加30%。Corso等[17]研究结果显示:乳腺癌后的第二原发癌主要为甲状腺癌、子宫内膜癌、肺癌、白血病、黑色素瘤、结直肠癌等。肺癌已成为全球重大健康问题,其发病率和死亡率在全球均较高。Wang等[18]发现虽然各分期乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌的生存率均远高于肺癌患者,但肺癌仍是乳腺癌确诊后发生原发性肺癌患者主要的死亡原因,所以研究乳腺癌幸存者发生第二原发性肺癌的风险越来越受到大家的关注。本研究首次系统评价和分析既往被诊断为原发性乳腺癌的女性发生原发性肺癌的风险。

在这项大规模以人群为基础的系统评价和Meta分析中,我们发现乳腺癌女性发生原发性肺癌的风险稍微高于一般人群,但乳腺癌患者的肺癌发病机制尚不清楚,这种风险的增加可能与多种因素相关。EGFR是肺癌最主要的驱动突变基因,EGFR突变和雌激素受体(ER)表达之间有很强的相关性[19]。He等发现,与男性肺癌患者相比,女性肺癌患者的EGFR突变发生显著增加,并且EGFR突变患者的ERβ1表达显著增加[20]。Rosell等[21]进行的一项随机试验表明,与接受他莫昔芬治疗2年的患者相比,接受他莫昔芬治疗5年的ER阳性乳腺癌患者发生第二原发性肺癌的发生率显著降低。因此,ER阳性乳腺癌患者应规范地接受内分泌治疗以期减少发生原发性肺癌的风险。对乳腺癌患者进行放疗虽然可降低乳腺癌局部复发率和死亡率,但是放疗也增加了暴露部位第二原发癌发生的风险[22]。Grantzau等[23]进行的一项Meta分析发现,在1954—2007年间包括113 516名接受过放疗的妇女和203 957名未接受放疗的妇女的11项研究中,与未接受放疗的乳腺癌妇女相比,接受过放疗的乳腺癌妇女随着时间的推移,发生原发性肺癌的风险逐渐增加。DiMarzio等[24]通过对10 676例乳腺癌患者进行回顾性分析发现,乳腺癌诊断后接受放疗的吸烟患者患肺癌的风险显著增加,所以在乳腺癌治疗中应全面评估患者的病情,避免过度治疗以减少放疗带来的额外风险。

在不同的研究中,根据乳腺癌确诊年龄对发生原发性肺癌风险的估计是不一致的,因此仅汇总了较少数量的研究。本研究观察到,乳腺癌确诊年龄 < 50岁的女性比≥50岁者患肺癌的风险更高,这可能与体内高水平雌激素以及ER高表达有关。有研究[25]表明,高水平雌激素是肺癌的一个驱动因素,可诱导非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)细胞增殖。The Women’s Health Initiate(WHI)对超过16 000名绝经后女性进行随机对照试验[26]发现,与接受安慰剂的女性相比,每天接受激素替代疗法(HRT)的女性增加了发生肺癌的风险并且NSCLC的死亡风险增加了60%,如停用HRT治疗后,肺癌死亡风险增加的情况有所缓解。Chu等[27]通过评估40 900例非转移性乳腺癌患者抗雌激素治疗对肺癌发病率的影响发现,乳腺癌患者使用抗雌激素治疗可以降低肺癌的风险。同时He等[28]通过临床样本数据分析提示,在一些NSCLC患者中,较高的ERα表达可能与较差的总生存率相关,并证明肺癌细胞和巨噬细胞通过ERα/CCL2/CCR2/MMP9和CXCL12/CXCR4途径相互作用可促进NSCLC的进展。因此,这些证据表明,雌激素及ER高表达可增加年轻乳腺癌女性发生肺癌的风险,同时也提示抗雌激素治疗在降低肺癌发生和死亡风险中发挥重要的作用。< 50岁确诊为乳腺癌的女性更有可能与基因有关[29]。因此,可以推测第二原发性肺癌的发病可能归因于遗传或家族危险因素。Maxwell等[30]通过比较单发乳腺癌患者与患有第二原发癌的乳腺癌患者是否存在癌症易感基因突变时发现,无论乳腺癌确诊年龄如何,患有第二原发癌的乳腺癌患者中发现BRCA1/2以外的基因突变率至少为7%,而乳腺癌确诊年龄 < 30岁的多原发癌患者的基因突变率高达25%。所以患有第二原发癌的乳腺癌患者不论发病年龄及有无家族史,均应进行多基因检测并接受遗传咨询。本研究还发现,与乳腺癌女性发生肺癌的总体风险相比,年长乳腺癌患者患肺癌的风险较低。其原因可能是中老年女性的随访时间较短以及未积极地接受治疗,减少了与肺癌发生风险相关的治疗因素。

本研究存在几项局限性。首先,本Meta分析所选定的研究均为回顾性队列研究,包括来自多中心和国家注册中心的数据。虽然这些研究的方法学质量总体上很高,但回顾性队列研究收集数据的真实性和可靠性的降低可能会影响报告数据的质量。其次,由于缺乏乳腺癌临床病理学特征以及治疗等必要的数据,未能明确乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌的风险因素,而且关于乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌预后的信息有限,因此通过定期复查进行早期诊断是否与提高生存率相关尚不清楚。

总而言之,这项包括远超过15万名乳腺癌患者的Meta分析发现,与一般女性人群相比,乳腺癌女性患第二原发性肺癌的风险有所增加。此外,确诊年龄 < 50岁的乳腺癌女性患第二原发性肺癌的风险更高。然而,关于乳腺癌的临床病理学特征与治疗在发生原发性肺癌风险中的影响仍需要进一步研究,以明确乳腺癌患者发生原发性肺癌的风险因素,为降低原发性肺癌的发病率提供依据。因此,这一较高的风险强调了针对年轻乳腺癌患者进行规范的治疗与密切的随访的重要性。

作者贡献:

刘金钊:文献检索、数据分析、文章撰写

张香梅、周雅荣:文献筛选、文献质量评价、数据分析

刘运江:指导课题设计及文章修改

| [1] |

Jain V, Kumar H, Anod HV, et al. A review of nanotechnology-based approaches for breast cancer and triple-negative breast cancer[J]. J Control Release, 2020, 326: 628-647. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.003 |

| [2] |

Cheng Y, Huang Z, Liao Q, et al. Risk of second primary breast cancer among cancer survivors: Implications for prevention and screening practice[J]. PLoS one, 2020, 15(6): e0232800. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0232800 |

| [3] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2020, 70(1): 7-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21590 |

| [4] |

Okamoto N, Morio S, Inoue R, et al. The risk of a second primary cancer occurring in five-year survivors of an initial cancer[J]. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 1987, 17(3): 205-213. |

| [5] |

Burt LM, Ying J, Poppe MM, et al. Risk of secondary malignancies after radiation therapy for breast cancer: Comprehensive results[J]. Breast, 2017, 35: 122-129. DOI:10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.004 |

| [6] |

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Mapping of reporting guidance for systematic reviews and meta-analyses generated a comprehensive item bank for future reporting guidelines[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2020, 118: 60-68. DOI:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.11.010 |

| [7] |

Yamada A, Komaki Y, Komaki F, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2018, 19(6): 758-767. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30188-8 |

| [8] |

DeVito NJ, Goldacre B. Catalogue of bias: publication bias[J]. BMJ Evid Based Med, 2019, 24(2): 53-54. DOI:10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111107 |

| [9] |

Schwartz AG, Ragheb NE, Swanson GM, et al. Racial and age differences in multiple primary cancers after breast cancer: A population-based analysis[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 1989, 14(2): 245-254. DOI:10.1007/BF01810741 |

| [10] |

Volk N, Pompe-Kirn V. Second primary cancers in breast cancer patients in Slovenia[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 1997, 8(5): 764-770. DOI:10.1023/A:1018487506546 |

| [11] |

Levi F, Te VC, Randimbison L, et al. Cancer risk in women with previous breast cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2003, 14(1): 71-73. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdg028 |

| [12] |

Schaapveld M, Visser O, Louwman MJ, et al. Risk of new primary nonbreast cancers after breast cancer treatment: a Dutch population-based study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2008, 26(8): 1239-1246. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9081 |

| [13] |

Lee KD, Chen SC, Chan CH, et al. Increased risk for second primary malignancies in women with breast cancer diagnosed at young age: a population-based study in Taiwan[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2008, 17(10): 2647-2655. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0109 |

| [14] |

Cluze C, Delafosse P, Seigneurin A, et al. Incidence of second cancer within 5 years of diagnosis of a breast, prostate or colorectal cancer: a population-based study[J]. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2009, 18(5): 343-348. DOI:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832abd76 |

| [15] |

Tabuchi T, Ito Y, Ioka A, et al. Incidence of metachronous second primary cancers in Osaka, Japan: update of analyses using population-based cancer registry data[J]. Cancer Sci, 2012, 103(6): 1111-1120. DOI:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02254.x |

| [16] |

Ricceri F, Fasanelli F, Giraudo MT, et al. Risk of second primary malignancies in women with breast cancer: Results from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)[J]. Int J Cancer, 2015, 137(4): 940-948. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29462 |

| [17] |

Corso G, Veronesi P, Santomauro GI, et al. Multiple primary non-breast tumors in breast cancer survivors[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2018, 144(5): 979-986. DOI:10.1007/s00432-018-2621-9 |

| [18] |

Wang R, Yin Z, Liu L, et al. Second Primary Lung Cancer After Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Study of 6, 269 Women[J]. Front Oncol, 2018, 8: 427. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2018.00427 |

| [19] |

Deng F, Li M, Shan WL, et al. Correlation between epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and the expression of estrogen receptor-β in advanced non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Oncol Lett, 2017, 13(4): 2359-2365. DOI:10.3892/ol.2017.5711 |

| [20] |

He C, He Y, Luo H, et al. Cytoplasmic ERβ1 expression is associated with survival of patients with Stage Ⅳ lung adenocarcinoma and an EGFR mutation at exon 21 L858R subsequent to treatment with EGFR-TKIs[J]. Oncol Lett, 2019, 18(1): 792-803. |

| [21] |

Rosell J, Nordenskjöld B, Bengtsson NO, et al. Long-term effects on the incidence of second primary cancers in a randomized trial of two and five years of adjuvant tamoxifen[J]. Acta Oncol, 2017, 56(4): 614-617. DOI:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1273547 |

| [22] |

Burt LM, Ying J, Poppe MM, et al. Risk of secondary malignancies after radiation therapy for breast cancer: Comprehensive results[J]. Breast, 2017, 35(10): 122-129. |

| [23] |

Grantzau T, Overgaard J. Risk of second non-breast cancer among patients treated with and without postoperative radiotherapy for primary breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies including 522, 739 patients[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2016, 121(3): 402-413. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2016.08.017 |

| [24] |

DiMarzio P, Peila R, Dowling O, et al. Smoking and alcohol drinking effect on radiotherapy associated risk of second primary cancer and mortality among breast cancer patients[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2018, 57: 97-103. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2018.10.002 |

| [25] |

Smida T, Bruno TC, Stabile LP. Influence of estrogen on the NSCLC microenvironment: a comprehensive picture and clinical implications[J]. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 137. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2020.00137 |

| [26] |

Chlebowski RT, Wakelee H, Pettinger M, et al. Estrogen Plus Progestin and Lung Cancer: Follow-up of the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trial[J]. Clin Lung Cancer, 2016, 17(1): 10-17. e1. DOI:10.1016/j.cllc.2015.09.004 |

| [27] |

Chu SC, Hsieh CJ, Wang TF, et al. Antiestrogen use in breast cancer patients reduces the risk of subsequent lung cancer: A population-based study[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2017, 48: 22-28. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2017.02.010 |

| [28] |

He M, Yu W, Chang C, et al. Estrogen receptor α promotes lung cancer cell invasion via increase of and cross-talk with infiltrated macrophages through the CCL2/CCR2/MMP9 and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling pathways[J]. Mol Oncol, 2020, 14(8): 1779-1799. DOI:10.1002/1878-0261.12701 |

| [29] |

Watanabe T, Honda T, Totsuka H, et al. Simple prediction model for homologous recombination deficiency in breast cancers in adolescents and young adults[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2020, 182(2): 491-502. DOI:10.1007/s10549-020-05716-0 |

| [30] |

Maxwell KN, Wenz BM, Kulkarni A, et al. Mutation Rates in Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Patients With Breast Cancer With Multiple Primary Cancers[J]. JCO Precis Oncol, 2020, 4: PO.19.00301. |

2021, Vol. 48

2021, Vol. 48