文章信息

- 女性乳腺癌流行病学趋势及危险因素研究进展

- Research Progress on Epidemiological Trend and Risk Factors of Female Breast Cancer

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2021, 48(1): 87-92

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2021, 48(1): 87-92

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2021.20.0498

- 收稿日期: 2020-05-12

- 修回日期: 2020-10-10

乳腺癌是全球女性最常见的癌症,2018年全球女性乳腺癌发病率和死亡率分别为46.3/105和13.0/105,且均呈上升趋势[1]。GLOBOCAN 2018年数据显示,发达国家(日本除外)发病率大于80.0/105,而在大多数发展中国家则低于40.0/105。虽然中国女性乳腺癌发病率(36.1/105)和死亡率(8.8/105)在世界范围内相对较低,但是均呈上升趋势,年度变化百分比分别为3.9%和1.1%。由于人口基数大,中国女性乳腺癌发病人数及死亡人数均居世界首位,分别占世界女性乳腺癌发病和死亡人数的17.6%和15.6%[2-3]。近年来,女性乳腺癌的发病率急剧上升,疾病负担也日益增加,已成为全球重点公共卫生问题。本综述旨在探讨世界范围内乳腺癌的流行病学、相关危险因素等,以期了解乳腺癌的流行现状,为乳腺癌的预防和早诊早治提供帮助。

1 女性乳腺癌流行病学 1.1 全球女性乳腺癌发病及死亡概况2000—2018年全球女性乳腺癌发病人数急剧上升,从2000年的105万上升至2018年的209万,但是死亡人数有所降低,2000年全球女性乳腺癌死亡人数为37万,2012年增至约52万,2018年死亡人数减少至31万,见图 1[1, 4-7]。最新数据显示,2018年全球新确诊女性乳腺癌病例约209万,世标发病率为46.30/105,0~74岁累积风险为5.03%,是女性最常见的癌症;死亡人数约63万,世标死亡率为13.00/105,0~74岁累积风险为1.41%,居女性恶性肿瘤死亡的首位[1]。

全球大部分国家,乳腺癌为女性癌症标化发病率第一的癌症,仅有少数国家以宫颈癌或肝癌为女性最常见的癌症。全球104个国家,乳腺癌为女性第一位恶性肿瘤死因,44个国家宫颈癌为第一死因,29个国家为肺癌,一些国家为胃癌、肝癌和结直肠癌[2]。

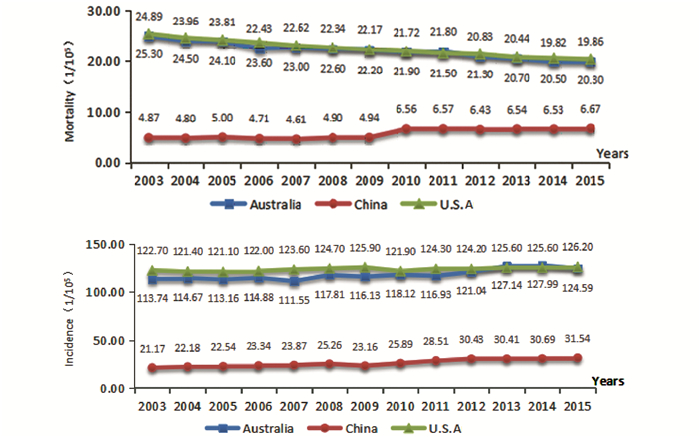

1.2 不同地区女性乳腺癌发病及死亡情况乳腺癌绝大多数发生在女性,男性乳腺癌属罕见的恶性肿瘤,约占所有乳腺癌的1%[8]。2018年,亚洲发病人数为91.1万,占全球女性乳腺癌新发病例的43.6%,死亡人数为31万,占全球女性乳腺癌死亡病例的49.6%,发病及死亡人数均居各大洲首位,并且亚洲国家的发病率一直呈上升趋势,乳腺癌是亚洲癌症死亡的第二大原因[2]。不同国家间女性乳腺癌发病及死亡情况也不同。据美国癌症协会分析,2020年美国预计将发生180.66万例新癌症病例和60.65万例癌症死亡病例,其中女性乳腺癌新发病例约为27.65万,女性死亡病例约为4.22万[9]。澳大利亚最新数据显示,2019年澳大利亚女性乳腺癌预估发病人数约为1.9万,发病率为130.80/105,与2003年的113.74/105相比,发病率增加约15.0%;女性乳腺癌预计死亡人数约为3000,死亡率为18.80/105,与2003年的24.89/105相比,死亡率降低约24.47%[10]。2003年至今,美国、澳大利亚女性乳腺癌的发病人数及死亡人数均持续上升,发病率也略有增长,但是死亡率有所下降[9-11]。与中国相比,虽然美国、澳大利亚的女性乳腺癌发病率和死亡率均远高于中国,且三个国家的乳腺癌发病率均呈上升趋势,但是美国和澳大利亚的女性乳腺癌死亡率略有下降,而中国的乳腺癌死亡率却有上升趋势,见图 2。

乳腺癌发病率和死亡率有明显的种族差异。美国癌症协会研究报告显示,白人女性乳腺癌发病率最高(约130.8/105),其次是黑人女性(126.7/105),美洲印第安人/阿拉斯加土著人女性、西班牙及亚洲/太平洋岛民女性发病率基本持平(均为94.0/105左右)。黑人女性乳腺癌死亡率最高,比白人女性死亡率高40%,比亚洲/太平洋岛民女性患者的死亡率高一倍以上[20]。移民的亚裔美国女性比美国出生的亚裔女性患乳腺癌的风险更高[21]。

1.4 乳腺癌分型及预后乳腺癌是一种具有多种分子分型的异质性疾病,主要分为管腔A、管腔B、HER2过表达和三阴性乳腺癌,各亚型预后不同[22]。其中三阴性乳腺癌(TNBC)被定义为雌激素受体(ER)阴性、孕激素受体(PR)阴性和缺乏人表皮生长因子受体2(HER2)过表达,与管腔A、管腔B、HER2过表达等主要乳腺癌亚型相比,预后相对较差[23]。黑人三阴性乳腺癌的发病率比白人高一倍左右。在20岁及以上的女性中,白人女性HR+/HER2-乳腺癌的发病率最高,比黑人女性发病率高23%,比西班牙裔女性和美洲印第安人/阿拉斯加土著人女性的发病率高45%左右[20]。

相对于晚期癌症而言,早期癌症更容易治疗,并且生存机会更高。2009—2015年美国Ⅰ期乳腺癌患者5年生存率为98%,Ⅱ期为92%,Ⅲ期为75%,而Ⅳ期仅为27%[20]。2009—2015年女性乳腺癌总体5年生存率为90%,其中白人5年生存率为91%,黑人仅为82%[9]。2005—2010年法国女性乳腺癌5年生存率为88%,10年生存率为78%,是西欧国家中生存率最高的国家之一[24]。2010—2014年中国女性乳腺癌的总体5年生存率仅为83.2%[25]。

第三轮全球癌症生存分析结果显示,2010—2014年确诊为乳腺癌的女性患者5年生存率大于85%的国家和地区约有25个,其中,亚洲国家包括日本、以色列和韩国。中国2010—2014年乳腺癌5年生存率在亚洲处于中游位置,高于新加坡、泰国、印度等国家[25]。

2 乳腺癌相关危险因素 2.1 人口学特征年龄是已知的重要的危险因素,乳腺癌发病率随年龄增长而增加[8]。绝经后妇女乳腺癌患病风险增加约50%[26]。“ABO”血型系统中,血型“A”的乳腺癌发生率最高(45.88%),血型“AB”的乳腺癌发生率最低(6.27%);RH血型系统中,RH阳性血型的乳腺癌发生率高(88.31%),而RH阴性血型者乳腺癌发生率低(11.68%),乳腺癌筛查过程中应重点关注血型“A”及RH阳性者,因为这些女性发生乳腺癌的可能性更大[27]。2004—2015年土耳其的一项全国性回顾研究显示,乳腺癌的类型、分级、分期和激素状态与ABO血型没有显著相关性;但RH阳性乳腺癌患者的小叶性乳腺癌发生率、肿瘤细胞雌激素受体(ER)过表达及转移约是RH阴性患者患病风险的2倍[28]。

不同人群乳房腺体密度分布各有差异,但是大多数女性乳房密度为少量腺体型,乳房极度致密者患乳腺癌风险最高,患癌风险约为少量腺体型的两倍,是乳房基本为脂肪者的三倍,多量腺体型患癌风险仅次于极度致密型。若所有乳房极度致密型的女性都转变成少量腺体性乳房,则可能避免约40%的绝经前乳腺癌和26%的绝经后乳腺癌[26]。

2.2 饮食、药物水果、蔬菜、全谷物(如豆浆、豆制品等)和膳食纤维摄入量较高者患乳腺癌的风险较低,而大量摄入红肉、动物脂肪和精制碳水化合物与增加患病风险有关[29-30]。随着饮食中总脂肪摄入量的增加,乳腺癌的发病率增加[31]。具有高热量食物(包括红色和(或)加工的肉类、高脂乳制品、土豆和糖果)的西方或类似西方的饮食模式会使乳腺癌风险增加约14%,而大量摄入水果、蔬菜、鱼类、全谷类食品和低脂乳制品等食物的健康饮食习惯可使乳腺癌风险降低约18%[32]。最近研究表明,随着发达国家向高热量西方饮食发展,乳腺癌发病率正在上升[31]。饮食中较高的天然叶酸、维生素B、核黄素、维生素D和钙水平则与降低乳腺癌患病风险有关[33]。

邻苯二甲酸酯是一种普遍存在的,具有多种化学和毒理学特征的工业化学品,用于许多消费品(如个人护理产品、食品容器、玩具、塑料制品和医疗器械等),不与其他成分共价结合,容易从产品中浸出,导致人体暴露[34-35]。研究表明,大多数邻苯二甲酸酯暴露与乳腺癌发病率无关,但高剂量邻苯二甲酸二丁酯接触(≥10 000累计毫克)与雌激素受体阳性乳腺癌发病率增加约两倍相关[35]。双膦酸盐可抑制破骨细胞的骨吸收,通常用于治疗绝经后骨质疏松症,也可通过影响肿瘤的凋亡、增殖和侵袭等发挥一定的抗肿瘤活性[36-37]。法国大量使用低剂量双膦酸盐来控制低骨密度,并建议将高剂量双膦酸盐作为辅助性乳腺癌治疗的一部分,但是在一项评估双膦酸盐与乳腺癌发病率关系的前瞻性队列研究中并没有发现使用双膦酸盐与乳腺癌发病率降低有关[38]。

激素治疗患者的乳腺癌患病风险比从未使用过的患者高[39]。雌激素与孕激素一起使用会增加非洲裔美国女性的ER+乳腺癌患病风险,但与ER-乳腺癌患病风险无关,单独使用雌激素与ER+或ER-乳腺癌患病风险均无关[40]。中性鱼精蛋白锌胰岛素(NPH)胰岛素和长效胰岛素类似物甘精胰岛素及Detemir(地特胰岛素)均属于基础胰岛素,通常用于治疗1型糖尿病和晚期2型糖尿病患者,英国的一项队列研究表明,与使用NPH胰岛素相比,治疗糖尿病时使用甘精胰岛素与女性乳腺癌患病风险增加相关,增加约1.5倍[41]。

2.3 生活方式因素主动吸烟或被动吸烟均会增加乳腺癌的患病风险,但是乳腺癌患者戒烟可降低其死亡风险[24]。饮酒者乳腺癌的患病风险比非饮酒者高约3倍[30, 42]。经常进行体育锻炼也可降低乳腺癌患病风险,活动强度较高者乳腺癌患病风险降低幅度较大[24, 29]。昼夜节律紊乱会增加乳腺癌患病风险,早起是乳腺癌的保护因素,睡眠持续时间延长会增加乳腺癌患病风险,但具体延长多久时间有待进一步研究[43]。

初潮年龄越小,乳腺癌患病风险越大,初潮年龄低于12岁者乳腺癌患病风险是初潮年龄在12岁以上者的两倍左右[42]。未产妇或首次生育年龄大于30岁者乳腺癌患病风险增加,而且首次分娩年龄大于30岁与乳腺癌患病风险相关性最大,是分娩年龄小于30岁者的6倍以上[26, 42]。首次分娩的年龄越大,乳腺癌患病风险越高,首次分娩年龄大于29岁的女性是首次分娩年龄小于20岁的女性患癌风险的3.53倍[23-24]。虽然分娩会降低乳腺癌的患病风险,但是与未产妇相比,经产妇在生产后5年乳腺癌患病风险会增加80%,生产24年后发生风险交叉,生产34年后患乳腺癌患病风险降低约25%[44]。

母乳喂养对乳腺癌具有保护作用,但是有研究表明母乳喂养仅能降低ER-乳腺癌患病风险,但不能降低ER+乳腺癌的患病风险[23, 45]。胎次和乳腺癌患病风险之间的关系存在争议[44]。

2.4 家族史及遗传因素家族性乳腺癌病例占15%~20%,遗传性病例占5%~10%,其中BRCA1和BRCA2种系的致病变异占遗传性乳腺癌的30%以上。在对其他与乳腺癌易感基因具有相似特性的基因进行深入研究发现,新的基因已经成为乳腺癌易感基因,包括罕见的生殖系高渗透基因突变(如TP53和PTEN),以及相对更多见的中度渗透基因突变渗透基因(如CHEK2、ATM和PALB2)[46]。有研究表明BRCA1和BRCA2中的种系致病变异会增加患乳腺癌的终生风险,CHEK2、ATM、BARD1和RAD51D的变异会使乳腺癌风险增加1~7倍,而MRE11A、RAD50、NBN、BRIP1、RAD51C、MLH1和NF1的变异与乳腺癌患病风险增加无关[47-48]。

一级亲属中有乳腺癌病史者与无家族史者相比,乳腺癌患病风险增加[23]。无乳腺癌家族史者对侧乳腺癌10年累积绝对风险为4.3%,有乳腺癌家族史者对侧乳腺癌的10年累积绝对风险为8.1%。若一级亲属在40岁以下被诊断为乳腺癌或双侧乳腺癌,患病风险进一步增加,约为无家族史者的3倍或9倍[49]。另外,乳腺癌的个体患病风险与患病亲属的数量和疾病的发病年龄成正比。在65~74岁女性中,脂肪型乳房的女性与一级家庭史相关的患病风险最高,HR为1.67,而在≥75岁的女性中,乳房致密者与家族史相关的患病风险最高,HR为1.55[50]。

3 小结随着生活方式、生育方式和环境暴露等因素的变化以及人口老龄化、人口增长,疾病发病率在未来很长一段时间内将会持续增加,疾病负担也会逐渐增加。虽然每个国家在乳腺癌防治方面都面临着巨大考验,但是不同国家所面临的情况又有所不同。美国、澳大利亚等发达国家的女性乳腺癌发病率及死亡率虽然一直很高,且发病率呈上升趋势,但这些国家在发病率不断上升的情况下仍能降低乳腺癌死亡率,足以证明他们在乳腺癌防治方面所采取的措施成效显著,值得我们深入研究学习。

乳腺癌的危险因素大致可分为遗传因素、环境因素以及行为生活方式因素等。年龄增大、初潮年龄小、未产妇或高龄产妇、乳房腺体密度致密、有乳腺癌家族史者、激素治疗患者、有吸烟和(或)饮酒行为者、高水平邻苯二甲酸脂暴露者以及高热量食物摄入较多者乳腺癌患病风险增加,但是经常进行体育锻炼、有母乳喂养、作息规律、摄入水果、蔬菜、全谷物及膳食纤维较多者可适当降低患乳腺癌风险。血型与乳腺癌风险间的关系缺乏足够证据。

通过研究乳腺癌的流行病学趋势,我们可以了解当前乳腺癌的流行病学现状。通过研究乳腺癌的危险因素,可以尽量减少增加乳腺癌发病率的相关行为,提倡不吸烟、不饮酒、不熬夜、多吃蔬菜水果谷物并加强锻炼,建议首次分娩年龄不要超过35岁、提倡母乳喂养等,以降低乳腺癌的发病率及死亡率,降低癌症负担,提高生活质量。

作者贡献

张雪:选题、资料收集及分析、论文撰写

董晓平、管雅喆:文献检索、资料收集及汇总录入

任萌:文献检索、英文翻译

郭冬利:文献检索及制图

贺宇彤:选题设计、论文审校

| [1] |

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI:10.3322/caac.21492 |

| [2] |

World Health Organization. Global Cancer Observatory (GCO): Cancer Today[EB/OL].2020-04-01]. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home.

|

| [3] |

Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. CA Cancer j Clin, 2016, 66(2): 115-132. DOI:10.3322/caac.21338 |

| [4] |

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2): 87-108. DOI:10.3322/caac.21262 |

| [5] |

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2011, 61(2): 69-90. DOI:10.3322/caac.20107 |

| [6] |

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global Cancer Statistics, 2002[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2005, 55(2): 74-108. DOI:10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74 |

| [7] |

Parkin DM. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2001, 2(9): 533-543. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7 |

| [8] |

Giordano SH. Breast Cancer in Men[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378(24): 2311-2320. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1707939 |

| [9] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2020[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2020, 70(1): 7-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21590 |

| [10] |

Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Breast Screen Australia monitoring report 2019[EB/OL].2020-04-01]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/breastscreen-australia-monitoring-report-2019/data.

|

| [11] |

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2013, 63(1): 11-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21166 |

| [12] |

Li T, Mello-Thoms C, Brennan PC. Descriptive epidemiology of breast cancer in China: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2016, 159(3): 395-406. DOI:10.1007/s10549-016-3947-0 |

| [13] |

陈万青, 郑荣寿. 中国女性乳腺癌发病死亡和生存状况[J]. 中国肿瘤临床, 2015, 42(13): 668-674. [Chen WQ, Zheng RS. Incidence, mortality and survival analysis of breast cancer in China[J]. Zhongguo Zhong Liu Lin Chuang, 2015, 42(13): 668-674.] |

| [14] |

Jia M, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Female breast cancer incidence and mortality in 2011, China[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2015, 7(7): 1221-1226. |

| [15] |

Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, et al. The incidence and mortality of major cancers in China, 2012[J]. Chin J Cancer, 2016, 35(1): 73. DOI:10.1186/s40880-016-0137-8 |

| [16] |

Zuo TT, Zheng RS, Zeng HM, et al. Female breast cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2013[J]. Thorac Cancer, 2017, 8(3): 214-218. DOI:10.1111/1759-7714.12426 |

| [17] |

郑荣寿, 孙可欣, 张思维, 等. 2015年中国恶性肿瘤流行情况分析[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2019, 41(1): 19-28. [Zheng RS, Sun KX, Zhang SW, et al. Report of cancer epidemiology in China, 2015[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2019, 41(1): 19-28.] |

| [18] |

李贺, 郑荣寿, 张思维, 等. 2014年中国女性乳腺癌发病与死亡分析[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2018, 40(3): 166-171. [Li H, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, et al. Incidence and mortality of female breast cancer in China, 2014[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2018, 40(3): 166-171. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2018.03.002] |

| [19] |

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, The National Cancer Institute (NCI). United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualizations[EB/OL].2020-05-01]. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html.

|

| [20] |

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2019, 69(6): 438-451. DOI:10.3322/caac.21583 |

| [21] |

Morey BN, Gee GC, von Ehrenstein OS, et al. Higher Breast Cancer Risk Among Immigrant Asian American Women Than Among US-Born Asian American Women[J]. Prev Chronic Dis, 2019, 16: E20. |

| [22] |

Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013[J]. Ann Oncol, 2013, 24(9): 2206-2223. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdt303 |

| [23] |

Badr LK, Bourdeanu L, Alatrash M, et al. Breast Cancer Risk Factors: a Cross-Cultural Comparison between the West and the East[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2018, 19(8): 2109-2116. |

| [24] |

Sancho-Garnier H, Colonna M. Épidémiologie des cancers du sein[J]. La Presse Médicale, 2019, 48(10): 1076-1084. DOI:10.1016/j.lpm.2019.09.022 |

| [25] |

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10125): 1023-1075. |

| [26] |

Engmann NJ, Golmakani MK, Miglioretti DL, et al. Population-Attributable Risk Proportion of Clinical Risk Factors for Breast Cancer[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2017, 3(9): 1228-1236. DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6326 |

| [27] |

Meo SA, Suraya F, Jamil B, et al. Association of ABO and Rh blood groups with breast cancer[J]. Saudi J Biol Sci, 2017, 24(7): 1609-1613. DOI:10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.01.058 |

| [28] |

Akin S, Kadri A. Clinical Associations with ABO Blood Group and Rhesus Blood Group Status in Patients with Breast Cancer: A Nationwide Retrospective Study of 3, 944 Breast Cancer Patients in Turkey[J]. Med Sci Monit, 2018, 24: 4698-4703. DOI:10.12659/MSM.909499 |

| [29] |

Tan MM, Ho WK, Yoon SY, et al. A case-control study of breast cancer risk factors in 7, 663 women in Malaysia[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(9): e0203469. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0203469 |

| [30] |

Heath AK, Muller DC, van den Brandt PA, et al. Nutrient-wide association study of 92 foods and nutrients and breast cancer risk[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2020, 22(1): 5. DOI:10.1186/s13058-019-1244-7 |

| [31] |

Shetty PJ, Sreedharan J. Breast Cancer and Dietary Fat Intake: A correlational study[J]. Nepal J Epidemiol, 2019, 9(4): 812-816. DOI:10.3126/nje.v9i4.26961 |

| [32] |

Xiao YJ, Xia JJ, Li LP, et al. Associations between dietary patterns and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2019, 21(1): 16. DOI:10.1186/s13058-019-1096-1 |

| [33] |

Houghton SC, Eliassen AH, Zhang SM, et al. Plasma B-vitamins and one-carbon metabolites and the risk of breast cancer in younger women[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2019, 176(1): 191-203. DOI:10.1007/s10549-019-05223-x |

| [34] |

Meeker JD, Sathyanarayana S, Swan SH. Phthalates and other additives in plastics: human exposure and associated health outcomes[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2009, 364(1526): 2097-2113. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2008.0268 |

| [35] |

Ahern TP, Broe A, Lash TL, et al. Phthalate Exposure and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(21): 1800-1809. DOI:10.1200/JCO.18.02202 |

| [36] |

Ott SM. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 374(21): 2095-2096. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1602599 |

| [37] |

Jha S, Wang Z, Laucis N, et al. Trends in Media Reports, Oral Bisphosphonate Prescriptions, and Hip Fractures 1996-2012: An Ecological Analysis[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2015, 30(12): 2179-2187. DOI:10.1002/jbmr.2565 |

| [38] |

Fournier A, Mesrine S, Gelot A, et al. Use of Bisphosphonates and Risk of Breast Cancer in a French Cohort of Postmenopausal Women[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(28): 3230-3239. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.4337 |

| [39] |

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10204): 1159-1168. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31709-X |

| [40] |

Rosenberg L, Bethea TN, Viscidi E, et al. Postmenopausal Female Hormone Use and Estrogen Receptor-Positive and -Negative Breast Cancer in African American Women[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2016, 108(4): djv361. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djv361 |

| [41] |

Wu JW, Azoulay L, Majdan A, et al. Long-Term Use of Long-Acting Insulin Analogs and Breast Cancer Incidence in Women With Type 2 Diabetes[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(32): 3647-3653. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4491 |

| [42] |

Thakur P, Seam RK, Gupta MK, et al. Breast cancer risk factor evaluation in a Western Himalayan state: A case-control study and comparison with the Western World[J]. South Asian J Cancer, 2017, 6(3): 106-109. DOI:10.4103/sajc.sajc_157_16 |

| [43] |

Richmond RC, Anderson EL, Dashti HS, et al. Investigating causal relations between sleep traits and risk of breast cancer in women: mendelian randomisation study[J]. BMJ, 2019, 365: l2327. |

| [44] |

Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Cai J, et al. Breast Cancer Risk After Recent Childbirth: A Pooled Analysis of 15 Prospective Studies[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2019, 170(1): 22-30. DOI:10.7326/M18-1323 |

| [45] |

Fortner RT, Sisti J, Chai B, et al. Parity, breastfeeding, and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor status and molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses' Health Studies[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2019, 21(1): 40. DOI:10.1186/s13058-019-1119-y |

| [46] |

Economopoulou P, Dimitriadis G, Psyrri A. Beyond BRCA: new hereditary breast cancer susceptibility genes[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2015, 41(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.10.008 |

| [47] |

Park JS, Lee ST, Nam EJ, et al. Variants of cancer susceptibility genes in Korean BRCA1/2 mutation-negative patients with high risk for hereditary breast cancer[J]. BMC Cancer, 2018, 18(1): 83. DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3940-y |

| [48] |

Chen X, Li Y, Ouyang T, et al. Associations between RAD51D germline mutations and breast cancer risk and survival in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancers[J]. Ann Oncol, 2018, 29(10): 2046-2051. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdy338 |

| [49] |

Reiner AS, Sisti J, John EM, et al. Breast Cancer Family History and Contralateral Breast Cancer Risk in Young Women: An Update From the Women's Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2018, 36(15): 1513-1520. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2017.77.3424 |

| [50] |

Braithwaite D, Miglioretti DL, Zhu W, et al. Family History and Breast Cancer Risk Among Older Women in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Cohort[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2018, 178(4): 494-501. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8642 |

2021, Vol. 48

2021, Vol. 48