文章信息

- 93例复发性卵巢癌疗效分析

- Efficacy of 93 Cases of Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2020, 47(1): 58-62

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2020, 47(1): 58-62

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2020.19.0797

- 收稿日期: 2019-06-17

- 修回日期: 2019-10-06

2. 215000 苏州, 苏州市相城人民医院妇产科

2. Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Suzhou Xiangcheng People'Hospital, Suzhou 215000, China

卵巢癌(ovarian cancer, OC)是死亡率较高的女性恶性肿瘤之一[1]。卵巢癌的初次治疗包括最大限度的肿瘤细胞减灭术并辅以铂类为基础的联合化疗, 70%~80%的卵巢癌患者经过初次治疗能获得临床缓解[2]。然而, 75%以上的上皮性卵巢癌(epithelial ovarian cancer, EOC)患者在初次治疗完全缓解后会发展为复发性卵巢癌(recurrent ovarian cancer, ROC)[3], 且多发生在初次治疗后的2年内[4]。ROC的最佳治疗仍然是一个不确定的领域, 很多患者在复发以后会选择多种方案的治疗, 但是, 个体化的最优方案选择是比较复杂的[5]。影响ROC预后的主要因素为对铂类为基础的化疗药物敏感度, 这一点对于ROC的指导治疗非常重要; 目前, 分子药物靶向治疗为卵巢癌的治疗提供了新的机会[6]。二次肿瘤细胞减灭术(secondary cytoreductive surgery, SCS)在ROC治疗中的作用尚不明确, 相关研究结果差异很大[7-8]。此外, 对预后的影响还包括其他因素, 如:组织分化、复发类型(可手术切除与不可手术切除)、复发部位、有无症状、既往治疗情况、年龄以及遗传毒性特征等[9]。

本研究通过回顾性分析93例ROC患者临床资料, 探讨不同临床病理特点对无瘤生存期(disease-free interval, DFI)的影响, 不同治疗方式对无进展生存期(progression-free survival, PFS)和复发后总生存时间(overall survival, OS)的影响, 旨在预测卵巢癌的易复发因素、延缓复发时间、优化复发后治疗方案、改善患者预后、提高患者临床缓解率和生存率。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料选择2008年1月-2018年6月在苏州大学附属第一医院妇科接受诊治、临床病理资料完整的ROC患者共93例为研究对象。所有病例均接受过满意的初次卵巢癌肿瘤细胞减灭术(primary cytoreductive surgery, PCS)并辅以铂类为基础的联合化疗, 且达到临床缓解期; 后经体格检查、影像学检查、肿瘤标志物检测及临床症状等确诊为复发, 复发后并接受了多种方案的治疗。所有患者均知情同意, 研究符合苏州大学附属第一医院伦理委员会的相关规定(伦理编号2018LS065)。

1.2 按照不同的治疗方式分组93例ROC患者确诊后, 给予多种治疗方法, 包括铂类为基础的化疗、SCS治疗、不同的分子靶向药物治疗。根据是否行SCS分为:手术组:SCS联合化疗和(或)靶向治疗(n=44);非手术组:化疗和(或)联合靶向药物治疗患者(n=49)。手术组患者中, 根据CA125水平分为:低水平组:CA125 ≤ 150 U/L(n=26);高水平组:CA125>150 U/L(n=18);根据SCS术前影像学检查提示复发肿瘤个数分为:少复发个数组:复发个数≤ 3(n=28);多复发个数组:复发个数>3(n=16)。

1.3 统计学方法采用SPSS22.0和Graphpad Prism Version 6.0统计学软件进行统计分析。描述性统计以数字、比例、均值、中位数表示。对ROC患者DFI影响因素单变量分析使用Mann-Whitney U及Kruskal-wallis H非参数检验, Kaplan-Meier法描绘两组患者复发后生存曲线, Log rank法检验复发后生存率差异, P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 临床资料手术组:年龄38~63岁, 中位数46岁, 平均年龄为44±9.47岁, 年龄: ≤ 50岁35例, >50岁9例; 分化程度:中高分化2例, 低分化42例; 有腹水3例, 无腹水41例; 复发时最大肿瘤直径:>2 cm的患者25例, ≤ 2 cm的患者19例; 复发时影像学提示复发肿瘤个数: ≤ 3个的患者28例, >3个的患者16例; 复发时CA125水平:CA125 ≤ 150 U/L的患者26例, CA125>150 U/L的患者18例; SCS术后残留病灶直径:>2 cm的患者5例, ≤ 2 cm的39例。非手术组:年龄36~72岁, 中位数55岁, 平均年龄为54.77±12.83岁, 年龄: ≤ 50岁27例, >50岁22例; 有腹水31例, 无腹水18例; 复发时影像学提示复发肿瘤个数: ≤ 3个的患者10例, >3个的患者39例; 复发时CA125水平:CA125 ≤ 150U/L的患者8例, CA125>150U/L的患者41例。

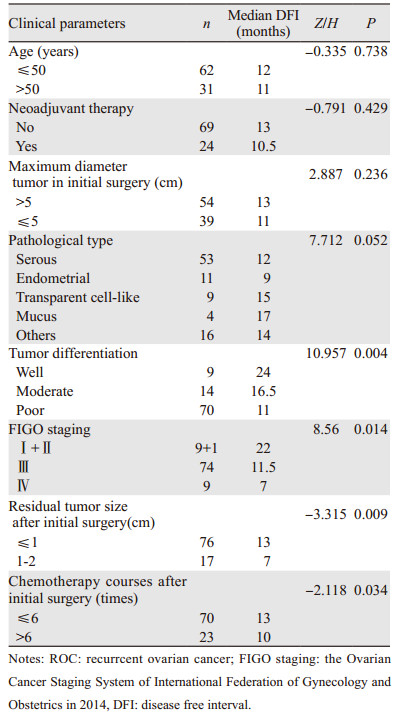

2.2 初次治疗后DFI单变量分析DFI单变量分析结果显示:病理分化程度、临床分期、初次术后残余肿瘤大小、初次术后化疗疗程数与DFI相关(P < 0.05)。肿瘤病理分化程度越高、临床分期越早、初次术后残余病灶越小、初次术后化疗数越规范足量, 卵巢癌患者的DFI越长。93例患者DFI影响因素的单变量分析结果见表 1。

|

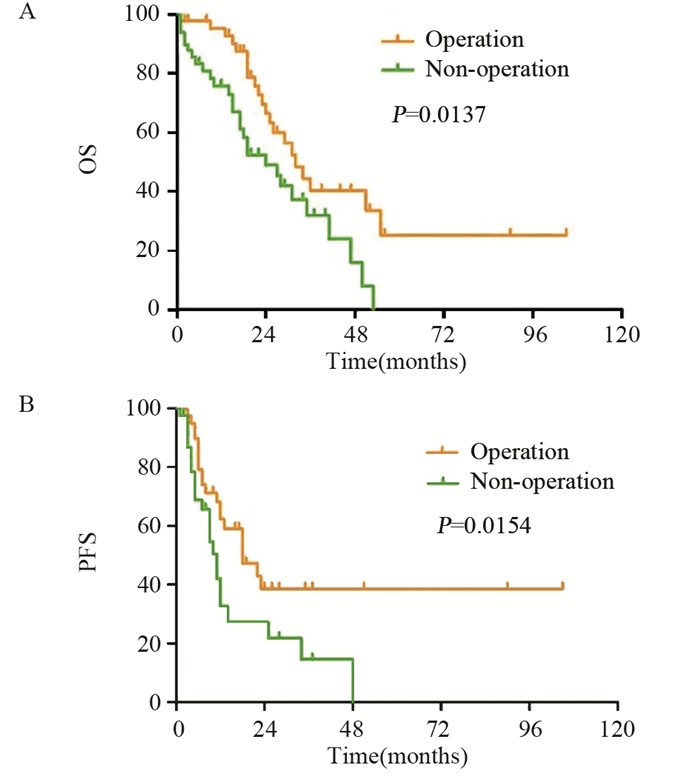

手术组和非手术组的中位PFS分别为18月(95% CI:8.09~27.91)和11月(95% CI:6.87~13.13)(χ2=7.30, P=0.0154);中位OS分别为32月(95% CI:24.63~39.37)和24月(95% CI:13.98~34.02)(χ2=6.08, P=0.0137)。手术组PFS和复发后OS均较非手术组延长, 差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05), 见图 1。

|

| 图 1 二次肿瘤细胞减灭术对复发性卵巢癌患者OS(A)和PFS(B)的影响 Figure 1 Effect of secondary cytoreductive surgery on OS (A) and PFS(B) of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer |

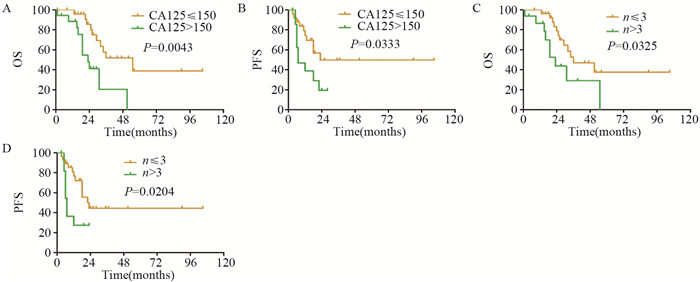

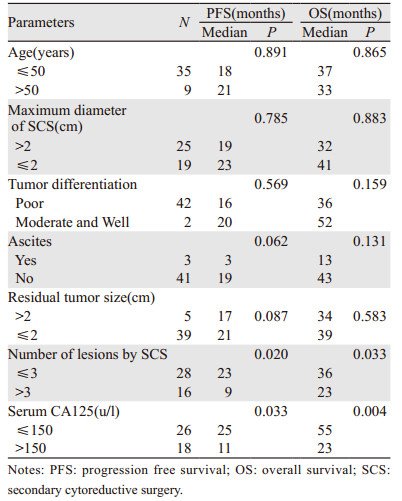

手术组中, 以PFS和OS为因变量, 进行单变量分析可能影响患者PFS和OS的各种因素, 见表 2。结果显示:年龄、复发时肿瘤最大直径、残留肿瘤直径、有无腹水、分化程度等与SCS预后无明显相关性; 相较于CA125>150 U/L的患者, CA125 ≤ 150 U/L的患者接受SCS后的OS和PFS均有所延长(P < 0.05);SCS术前影像学检查提示复发肿瘤个数≤ 3的患者较复发肿瘤个数>3的患者术后的OS和PFS均有所延长(P < 0.05), 见图 2。

|

| 图 2 复发性卵巢癌患者二次肿瘤细胞减灭术前的CA125水平(A, B)和病灶个数(C, D)对PFS和OS的影响 Figure 2 Effect of CA125 level(A, B) and number of lesions(C, D) on PFS and OS of ROC patients before secondary tumor cytoreductive surgery |

|

近十年来晚期卵巢癌的预后几乎没有改善, 虽然大多数患者对以铂类为基础的化疗敏感度较高, 但是仍然有很多患者随后复发[10]。目前国内外研究影响卵巢癌复发的因素众多, 探讨这些相关因素特点, 寻找其复发规律, 有助于早期发现ROC。最能预测EOC预后的因素包括:肿瘤生物学、组织学类型、术后残留肿瘤的数量、肿瘤分期等[11]。在接受首次手术治疗的EOC患者中, 满意的卵巢癌细胞减灭术, 尤其是无明显残留肿瘤的患者, 与OS和DFI显著相关[12-13], 无肉眼可见残余肿瘤的患者比最小残留病灶 < 1 cm和残留病灶>1 cm的患者显示出更好的生存率[12]。实现完全肿瘤细胞减灭取决于肿瘤的分子特征、肿瘤的微环境和实施手术者的水平[14-15]。本研究也得到时相同的结果, 患者肿瘤病理分化程度越高、临床分期越早、初次术后残余病灶越小、术后化疗疗程越规范足量的, DFI越长、复发越晚。

尽管ROC的PFS没有增加, 但是总生存时间有一定程度的延长, 这意味着卵巢癌总生存期的增加主要是得益于复发后的治疗[16]。复发性上皮性卵巢癌的治疗仍以化疗为主, 卵巢癌肿瘤细胞减灭术主要针对原发性卵巢癌, 由于前瞻性随机试验的数据缺失, 其在ROC中的作用存在争议[17-18]。越来越多的证据支持完全切除的SCS可以改善ROC患者的生存率[19]。Giudice等指出SCS能够改善铂类药物敏感型ROC患者复发后的生存率, 延长总生存时间, 尤其是在局部复发并且初次手术为完全切除的患者中获益更多[20-21]。本研究纳入的93例ROC患者中, 有44例患者接受了SCS加药物治疗, 较49例未行SCS仅给予药物治疗, 复发后PFS和OS均明显延长。由于部分患者并未在初次治疗缓解后严密随访, 导致复发时已经出现大量腹水、多处复发等情况, 而无再次手术的机会, 故初次治疗缓解后的严密随访显得尤为重要。

CA125水平的监测对卵巢癌术后复发及预后的影响仍存在争议。有学者认为CA125对EOC患者手术后的检测价值是必要的, 当CA125的值高于10 U/L并持续增加时, 需要警惕并应结合影像学检查(如PET-CT), 早期发现复发病灶和早期再治疗, 增加再次手术的机会, 该结果可改善复发患者的预后[22]。另有学者认为仅仅通过监测血清CA125的浓度对EOC术后复发的随访没有临床价值, 单一的CA125监测对复发的患者并没有生存获益[23]; 但是, SCS术前CA125水平可能是预测ROC患者预后因素之一, 术前CA125 ≤ 164.5 U/L的患者PFS和OS明显优于术前CA125>164.5 U/L, 术前CA125 < 164.5 U/L铂敏感的卵巢癌首次复发患者的PFS和OS明显改善[24]。本研究数据显示, 相较于CA125>150 U/L的患者, SCS术前CA125 ≤ 150 U/L的患者接受SCS后的OS和PFS均有所延长。

有关ROC的预后预测指标研究有很多, SCS完全切除是一个重要的预后因素[2], 复发时CA125水平、复发时有无腹水和肿瘤复发的个数均是ROC的独立预后因素[25-27], 二次减瘤术前的影像学检查非常有必要, 往往术中探查发现复发病灶个数大于影像学检查发现的个数[28]。本研究中44例接受SCS的患者, 术前均进行了不同的影像学检查, 肿瘤复发个数≤ 3个, 较复发个数>3的PFS和OS有所延长(P < 0.05)。

随着肿瘤分子生物学的发展, 多种靶向药物得到开发。靶向血管生成的药物, 如:抗VEGF抗体药物-贝伐单抗已被批准用于转移性结直肠癌、晚期非鳞状非小细胞肺癌、晚期卵巢癌等的一线治疗药物[29], 并且针对同源重组缺陷的药物, 如:PARP抑制剂已被批准用于铂类敏感度化疗后的卵巢癌的维持治疗[30], 且有明确的证据表明, 对于成人中无论有无BRCA1/2突变或同源重组缺陷的复发性铂类敏感度上皮卵巢癌的维持治疗, PARP抑制剂是一种有效的新选择[31]。但是, 在本研究由于样本量太少, 并没有证据支持以上观点。

综上所述, 上皮性卵巢癌患者肿瘤病理分化程度越高、临床分期越早、初次术后残余病灶越小、术后化疗疗程越规范足量的DFI越长、复发越晚。一般情况好, 复发时CA125 ≤ 150 U/L、影像学检查复发个数≤ 3个的患者能够从二次减瘤术中获益。

作者贡献

王娟:整理资料、分析数据、书写文章

陈友国:校对数据

查雪丽:收集资料

周金华:指导全文

| [1] |

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2): 87-108. DOI:10.3322/caac.21262 |

| [2] |

Takahashi A, Kato K, Matsuura M, et al. Comparison of secondary cytoreductive surgery plus chemotherapy with chemotherapy alone for recurrent epithelial ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal carcinoma:A propensity score-matched analysis of 112 consecutive patients[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2017, 96(37): e8006. |

| [3] |

Usami T, Kato K, Taniguchi T, et al. Recurrence patterns of advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers after complete cytoreduction during interval debulking surgery[J]. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2014, 24(6): 991-996. DOI:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000142 |

| [4] |

Ushijima K. Treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer-at first relapse[J]. J Oncol, 2010, 2010: 497429. |

| [5] |

Corrado G, Salutari V, Palluzzi E, et al. Optimizing treatment in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer[J]. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 2017, 17(12): 1147-1158. DOI:10.1080/14737140.2017.1398088 |

| [6] |

Stuart GC, Kitchener H, Bacon M, et al. 2010 Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus statement on clinical trials in ovarian cancer:report from the Fourth Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference[J]. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2011, 21(4): 750-755. DOI:10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821b2568 |

| [7] |

van de Laar R, Zusterzeel PL, Van Gorp T, et al. Cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for recurrent platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian cancer (SOCceR trial):a multicenter randomised controlled study[J]. BMC Cancer, 2014, 14: 22. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-14-22 |

| [8] |

Galaal K, Naik R, Bristow RE, et al. Cytoreductive surgery plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2010(6): CD007822. |

| [9] |

Harter P, Hilpert F, Mahner S, et al. Systemic therapy in recurrent ovarian cancer:current treatment options and new drugs[J]. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 2010, 10(1): 81-88. DOI:10.1586/era.09.165 |

| [10] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(1): 7-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21332 |

| [11] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(1): 5-29. DOI:10.3322/caac.21254 |

| [12] |

du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer:a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials:by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO)[J]. Cancer, 2009, 115(6): 1234-1244. DOI:10.1002/cncr.24149 |

| [13] |

Ataseven B, Chiva LM, Harter P, et al. FIGO stage Ⅳ epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer revisited[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2016, 142(3): 597-607. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.06.013 |

| [14] |

Kessous R, Laskov I, Abitbol J, et al. Clinical outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2017, 144(3): 474-479. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.12.017 |

| [15] |

Liu Z, Beach JA, Agadjanian H, et al. Suboptimal cytoreduction in ovarian carcinoma is associated with molecular pathways characteristic of increased stromal activation[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2015, 139(3): 394-400. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.08.026 |

| [16] |

Kyrgiou M, Salanti G, Pavlidis N, et al. Survival benefits with diverse chemotherapy regimens for ovarian cancer:meta-analysis of multiple treatments[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2006, 98(22): 1655-1663. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djj443 |

| [17] |

Cheng X, Jiang R, Li ZT, et al. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer (mEOC)[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2009, 35(10): 1105-1108. DOI:10.1016/j.ejso.2009.03.010 |

| [18] |

Lorusso D, Mancini M, Di Rocco R, et al. The role of secondary surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer[J]. Int J Surg Oncol, 2012, 2012: 613980. |

| [19] |

Bogani G, Rossetti D, Ditto A, et al. Artificial intelligence weights the importance of factors predicting complete cytoreduction at secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer[J]. J Gynecol Oncol, 2018, 29(5): e66. DOI:10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e66 |

| [20] |

Giudice MT, D'Indinosante M, Cappuccio S, et al. Secondary cytoreduction in ovarian cancer:who really benefits?[J]. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2018, 298(5): 873-879. DOI:10.1007/s00404-018-4915-1 |

| [21] |

Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7):overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(8): 928-936. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00086-8 |

| [22] |

Guo N, Peng Z. Does serum CA125 have clinical value for follow-up monitoring of postoperative patients with epithelial ovarian cancer? Results of a 12-year study[J]. J Ovarian Res, 2017, 10(1): 14. DOI:10.1186/s13048-017-0310-y |

| [23] |

Rustin GJ, van der Burg ME, Griffin CL, et al. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955):a randomised trial[J]. Lancet, 2010, 376(9747): 1155-1163. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61268-8 |

| [24] |

Parashkevova A, Sehouli J, Richter R, et al. Preoperative CA-125 Value as a Predictive Factor for Postoperative Outcome in First Relapse of Platinum-sensitive Serous Ovarian Cancer[J]. Anticancer Res, 2018, 38(8): 4865-4870. DOI:10.21873/anticanres.12799 |

| [25] |

Onda T, Yoshikawa H, Yasugi T, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma:proposal for patients selection[J]. Br J Cancer, 2005, 92(6): 1026-1032. DOI:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602466 |

| [26] |

Bristow RE, Peiretti M, Gerardi M, et al. Secondary cytoreductive surgery including rectosigmoid colectomy for recurrent ovarian cancer:operative technique and clinical outcome[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2009, 114(2): 173-177. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.004 |

| [27] |

Zang RY, Harter P, Chi DS, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer undergoing secondary cytoreductive surgery based on the pooled analysis of an international collaborative cohort[J]. Br J Cancer, 2011, 105(7): 890-896. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2011.328 |

| [28] |

Harter P, Beutel B, Alesina PF, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) score in surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2014, 132(3): 537-541. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.027 |

| [29] |

Loizzi V, Del Vecchio V, Gargano G, et al. Biological Pathways Involved in Tumor Angiogenesis and Bevacizumab Based Anti-Angiogenic Therapy with Special References to Ovarian Cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18(9): E1967. DOI:10.3390/ijms18091967 |

| [30] |

Basu P, Mukhopadhyay A, Konishi I. Targeted therapy for gynecologic cancers:Toward the era of precision medicine[J]. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2018, 143(Suppl 2): 131-136. |

| [31] |

Heo YA, Duggan ST. Niraparib:A Review in Ovarian Cancer[J]. Target Oncol, 2018, 13(4): 533-539. DOI:10.1007/s11523-018-0582-1 |

2020, Vol. 47

2020, Vol. 47