文章信息

- PD-L1表达与结直肠癌预后及临床病理特征关系的Meta分析

- Prognostic and Clinicopathological Significance of PD-L1 Expression for Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-analysis

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2019, 46(11): 1013-1021

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2019, 46(11): 1013-1021

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2019.19.0363

- 收稿日期: 2019-03-20

- 修回日期: 2019-06-04

结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)是导致癌症相关死亡的主要原因之一,到2030年,预计将有超过220万新病例和110万患者死亡[1-2]。CRC早期症状无特异性,许多患者错过最佳治疗时机,首次确诊就已属进展期[3]。大约50%的患者最后将转归为转移性结直肠癌(metastatic colorectal cancer, mCRC)[4]。大部分mCRC患者失去根治性手术的机会,预后不佳。mCRC的标准化疗方案有FOLFOX(奥沙利铂+氟尿嘧啶+亚叶酸钙)和FOLFIRI(伊立替康+氟尿嘧啶+亚叶酸钙)及XELOX等,随着抗血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)和表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)的单克隆抗体的研制和投入使用,标准化疗联合靶向治疗使mCRC患者的预后较前改善[5]。但总体而言,mCRC的预后仍不理想。近年来,免疫检查点阻断疗法获得重要进展,针对PD-1/PD-L1途径的免疫检查点阻断疗法在治疗人类实体瘤如恶性黑色素瘤、非小细胞肺癌、肾细胞癌、淋巴瘤、乳腺癌中获得了显著疗效[6]。2013年,《科学》杂志将癌症免疫治疗评为2013年的年度突破,免疫治疗已成为肿瘤治疗的热点[7]。对CRC而言,PD-1抑制剂Pembrolizumab和Nivolumab已被第七版NCCN指南推荐作为错配修复缺陷/微卫星高度不稳定(dMMR/MSI-H)分子表型mCRC的后线治疗。然而CRC是一种分子高度异质性的疾病,不同分子表型的患者对免疫治疗的反应可能截然不同,为筛选靶向免疫治疗的获益人群,寻找新的预测因子成为目前的研究方向之一。

PD-L1也称为CD274或B7-H1,是PD-1的主要配体,是一种负性免疫调节蛋白。PD-L1常表达于肿瘤细胞、树突状细胞、巨噬细胞、纤维母细胞和T细胞等[8-9]。肿瘤通过上调PD-L1表达,与PD-1结合后,抑制T细胞活化,限制自身免疫的强度,减弱免疫系统对肿瘤细胞的监视作用,从而发生免疫逃逸[10-14]。这与肿瘤发生、发展有关,并且是恶性肿瘤预后不良的潜在原因。PD-L1是CRC潜在的预测因子,目前已公开发表的研究针对PD-L1表达与CRC的预后关系的观点尚有争议。一部分研究认为PD-L1表达与CRC的不良生存有关[15-24],但其他研究的观点与之相左[25-32]。

为了提供大样本数据来探讨PD-L1作为CRC预测因子的意义价值,本研究运用Meta分析的方法,对已公开发表的关于PD-L1表达与CRC预后的研究数据进行合并,评估CRC中PD-L1表达的预后及相关临床病理参数意义。

1 资料与方法 1.1 文献检索策略系统检索PubMed、Embase、Cochrane Library、CNKI和万方数据库,筛选有关PD-L1表达与CRC预后关系的研究。检索时间截止于2018年6月。检索词为“colorectal cancer”、“colorectal tumor”、“colorectal neoplasm”、“colorectal carcinoma”、“colon cancer”、“rectal cancer”、“PD-L1”、“programmed cell death receptor 1 ligand 1”、“CD274”、“B7-H1”、“prognosis”、“prognostic”以及对应的中文检索词。

1.2 文献纳入标准(1)所有纳入患者病理确诊为结直肠癌;(2)标本来源于肿瘤组织,通过免疫组织化学(immunohistochemistry, IHC)方法检测PD-L1表达;(3)文中提供了可供分析的生存资料,如OS、RFS或者DFS的HR与其95%CI,探讨了PD-L1表达与CRC预后和(或)相关临床病理参数之间的关系;(4)纳入文献的出版语言仅限于中文和英文。

1.3 文献排除标准(1)病例报道、综述、会议摘要、重复发表的文献;(2)动物试验;(3)无法获取可供分析的生存资料;(4)标本来源于血液。

1.4 数据提取两位研究人员按设定的标准独立地筛选文献,提取数据。出现不同观点时,可进行小组讨论,解决争议,以减小数据提取时出现的误差而增大异质性,影响最终结果。首先,去除重复的文献,进而阅读文章题目、摘要,以排除不符合本研究要求的文献,最后阅读全文,仔细甄别满足纳入要求的研究。提取的数据包括:(1)基本信息:第一作者、国家、出版时间、抗体类型、随访时间、PD-L1阳性率和截断值;(2)相关临床病历资料:各研究性别比例、病例数;(3)病理特征资料:肿瘤大小、TNM分期、浸润深度、肿瘤分化程度、血管侵犯、淋巴结转移、是否化疗、MSI状态、KRAS突变情况等。(3)生存预后资料:OS(overall survival)、RFS(relapse-free survival)和DFS(disease-free survival)的HR及其95%CI。

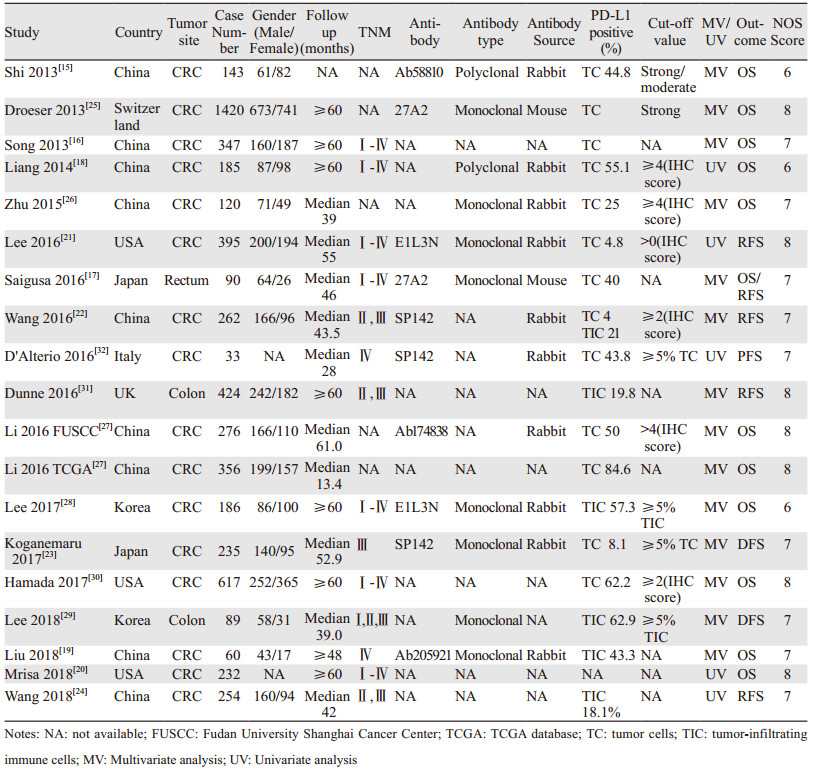

1.5 文献质量评价使用纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(NOS)来评估所纳入文献的质量,量表包括selection、comparability和outcome assessment三个参数,总分为9分,文献评分在6分以上视为高质量。质量评估由2名研究人员独立进行,小组讨论解决评分不一致的情况,排除低质量文献后确定最终纳入文献。各纳入文献评分见表 1。

采用风险比(HR)及其95%CI来评价PD-L1表达与结直肠癌OS、RFS和DFS的关系,生存数据均从文献中直接获得。比值比(OR)及其95%CI用于评估PD-L1表达与结直肠癌相关的临床病理学特征之间的关系。有统计学意义的异质性定义为卡方检验P < 0.1或I2 > 50%。假如观察到异质性,我们利用随机效应模型来减少异质性对结果的影响,否则,使用固定效果模型。Egger's和Begg's检验用于评估发表偏倚。使用Stata SE12.0软件进行全部的统计分析。

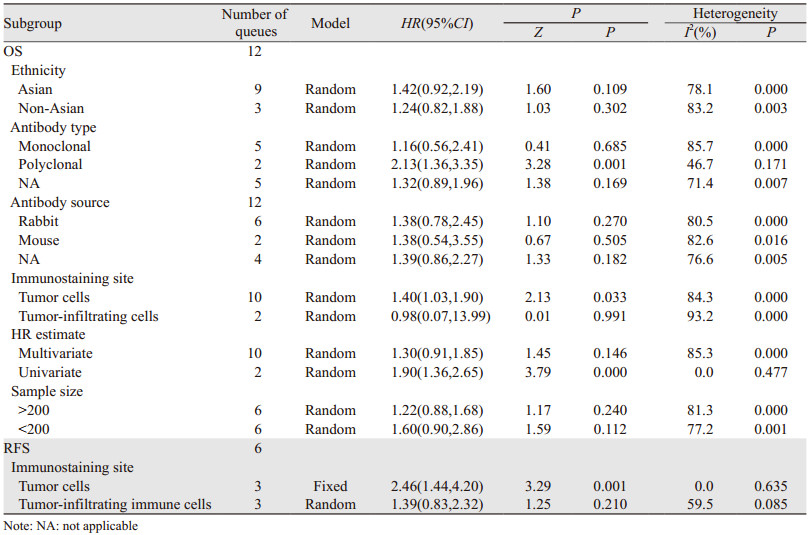

2 结果 2.1 纳入文献一般特征初步检索得到252篇文献,首先去除32篇重复文献,阅读题目和摘要后去除122篇,阅读全文后排除80篇,最终纳入18项研究[15-32]。其中12篇来自亚洲[15-19, 22-24, 26-29],3篇来自美国[20-21, 30],3篇来自欧洲[25, 31-32]。文献检索流程见图 1(For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org)。纳入文献发表于2013至2018年间,共5 724例CRC患者纳入分析,PD-L1阳性率在4.0%至84.6%之间,各文献一般特征见表 1。

|

| 图 1 文献检索流程图 Figure 1 Flow diagram of literature search and selection |

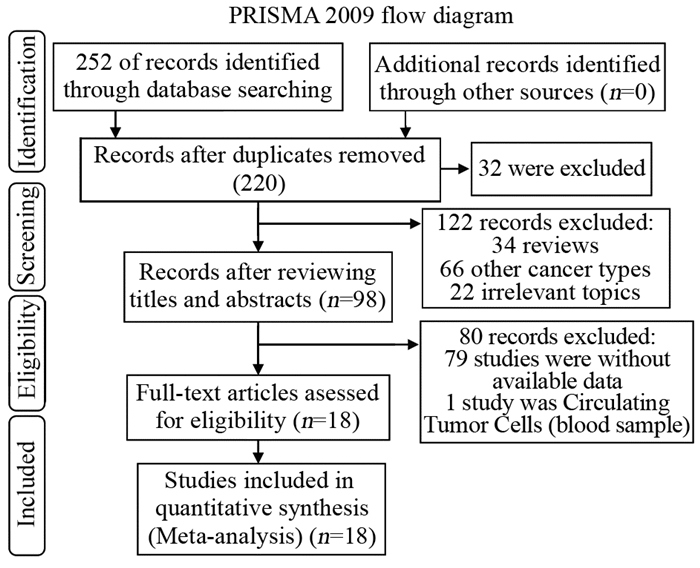

共11项研究(12个队列)报道了PD-L1表达与OS的关系,纳入样本量为4 032例。结果提示:与PD-L1阴性组相比,PD-L1阳性表达与CRC更短的OS相关,差异有统计学意义(HR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.02~1.93, P=0.039),见图 2A。共5项研究(6个队列)报道PD-L1表达与RFS的关系,纳入样本量为1 425例。结果提示PD-L1表达与CRC较短的RFS有关,差异有统计学意义(HR: 1.67, 95%CI: 1.27~2.20; P=0.000),见图 2B。4项研究报道了PD-L1表达与DFS的关系,共785例样本。结果提示PD-L1表达与DFS无统计学意义的关联(HR: 1.16, 95%CI: 0.60~2.27, P=0.659),见图 2C。在关于OS(I2=86.0%)和DFS(I2=81.0%)的分析中观察到高异质性,故采用随机效应模型,而关于RFS(I2=41.6%)的分析中无高异质性,则采用固定效应模型。

|

| A: overall survival; B: relapse-free survival; C: disease-free survival 图 2 PD-L1表达与结直肠癌生存关系的Meta分析森林图 Figure 2 Meta-analysis of relation between PD-L1 expression and prognosis of colorectal cancer |

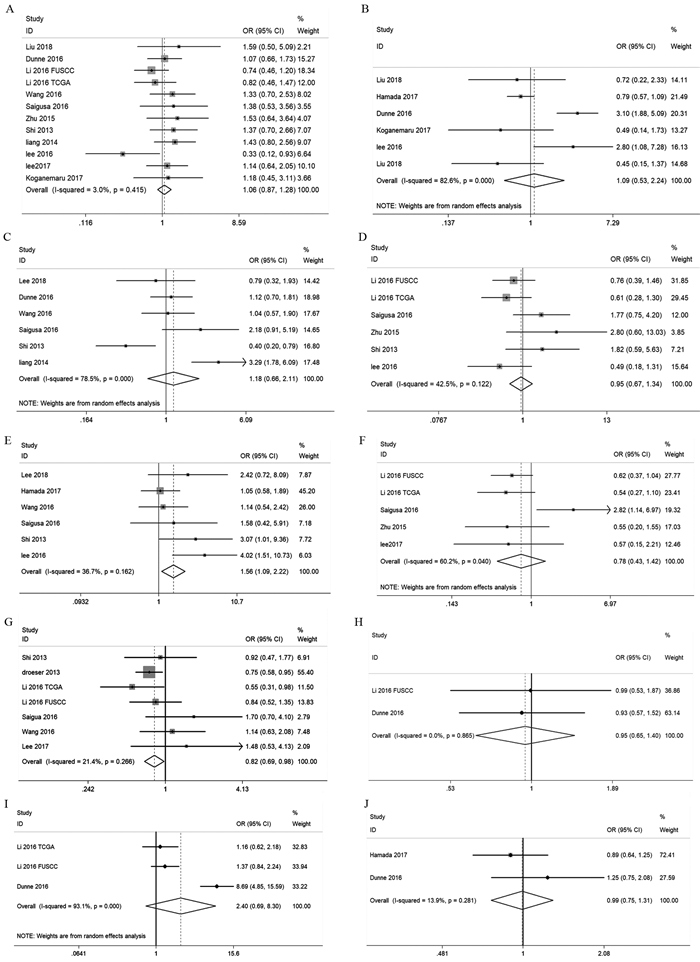

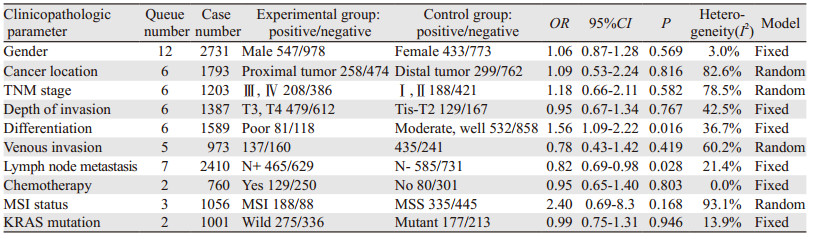

从性别、肿瘤位置、TNM分期、肿瘤浸润深度、肿瘤分化、血管侵犯、淋巴结转移、化疗、MSI状态、KRAS突变等10个方面分析PD-L1表达与CRC临床病理参数之间的关系。结果提示:PD-L1表达与肿瘤分化(OR: 1.56, 95%CI: 1.09~2.22, P=0.016)及淋巴结转移(OR: 0.82, 95%CI: 0.69~0.98, P=0.028)有关。而在性别(OR: 1.06, 95%CI: 0.87~1.28, P=0.569)、肿瘤位置(OR: 1.09, 95%CI: 0.53~2.24, P=0.816)、TNM分期(OR: 1.18, 95%CI: 0.66~2.11, P=0.582)、浸润深度(OR: 0.95, 95%CI: 0.67~1.34, P=0.767)、血管侵犯(OR: 0.78, 95%CI: 0.43~1.42, P=0.419)、化疗(OR: 0.95, 95%CI: 0.65~1.40, P=0.803)、MSI状态(OR: 2.4, 95%CI: 0.69~8.3, P=0.168)、KRAS突变(OR: 0.99, 95%CI: 0.75~1.31, P=0.946)等方面,PD-L1表达与其无统计学意义的关联,见图 3、表 2。

|

| A: gender; B: cancer location; C: TNM stage; D: depth of invasion; E: differentiation; F: venous invasion; G: lymph node metastasis; H: chemotherapy; I: MSI status; J: KRAS mutation 图 3 PD-L1表达与相关临床病理参数关系的Meta分析 Figure 3 Forest plots of correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics |

|

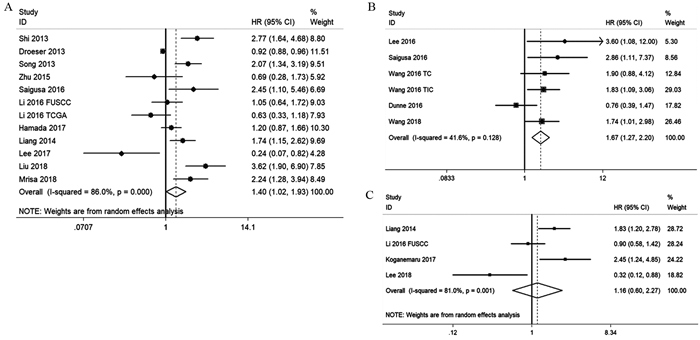

PD-L1表达与OS相关性分析中,观测到显著异质性(I2=86.0%),为明确异质性来源,我们按种族、抗体类型、抗体来源、免疫染色位置、HR评估、样本大小分组,亚组分析结果提示在肿瘤细胞中PD-L1表达(HR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.03~1.90)多克隆抗体(HR: 2.13, 95%CI: 1.36~3.35)及单因素分析(HR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.36~2.65)亚组中,PD-L1表达与OS的关联有统计学意义,并且在多克隆抗体(I2=46.7%)及单因素分析(I2=0.0%)亚组中,异质性显著下降,由此推断抗体类型及HR评估类型是PD-L1表达与OS相关性分析中的主要异质性来源。同时我们发现,肿瘤细胞中的PD-L1表达和肿瘤浸润免疫细胞中的表达与OS的关系存在不一致性,为进一步探讨这一现象,按免疫染色位置不同也对PD-L1表达与RFS的关系进行亚组分析,结果证实肿瘤细胞中PD-L1表达与较短的RFS有关(HR: 2.46, 95%CI: 1.44~4.20),而肿瘤浸润免疫细胞中的表达与RFS(HR: 1.39, 95%CI: 0.83~2.32)无统计学的关联,见表 3。

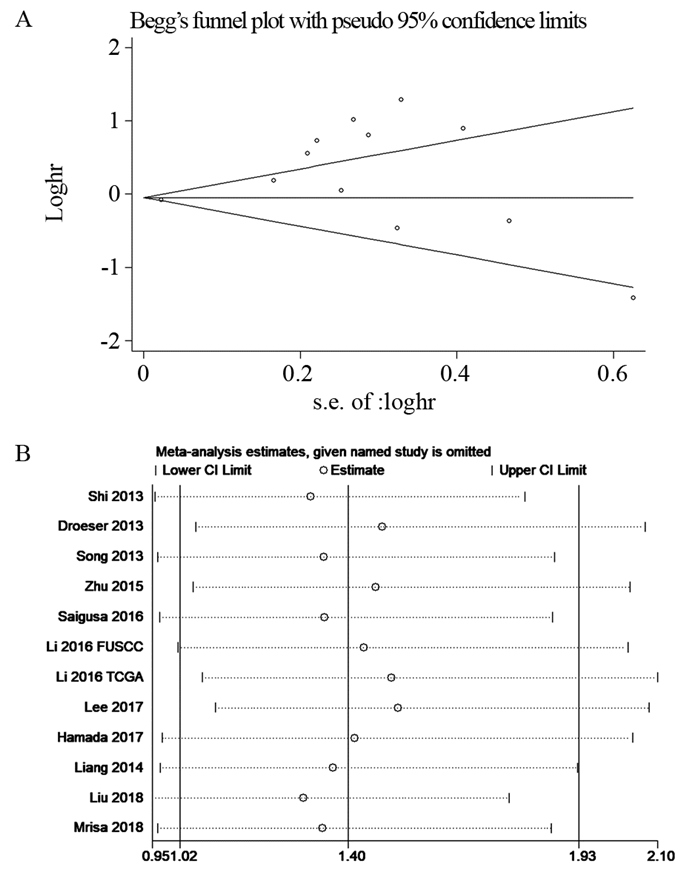

使用Egger's test和Begg's test来评估发表偏倚。Begg's试验结果表明在评估OS的研究中存在潜在的发表偏倚(Begg's test, Pr > |z|=0.041),而Egger's试验结果与之相反,提示没有发表偏倚(Egger's test, Pr > |z|=0.945)。对于此矛盾,进一步的Begg's图显示出不对称性,这支持了Begg's试验的结论,见图 4A。发表偏倚存在的原因可能是由于阳性结果相比阴性结果更容易发表。当研究数量少于10项时,定性和定量检测的敏感度很低,因此我们没有评估RFS和DFS的发表偏倚[33]。

|

| 图 4 PD-L1表达与OS关系的偏倚(A)及敏感度(B)分析图 Figure 4 Begg's plots(A) and sensitivity(B) analyses of relationship between PD-L1 expression and OS |

采用Stata SE12.0软件对OS进行敏感度分析,逐次剔除1篇文献,制作森林图来评估各项研究对合并结果的影响。森林图提示在剔除任何一项研究后,对合并的HR和95%CI均没有显著影响,表明Meta分析结果的稳定性,见图 4B。

3 讨论抑制性受体的表达可以激活共刺激因子的活性,限制T细胞的迁移、增殖和细胞毒性介质的释放,从而阻止过度的自身免疫、炎性反应和避免组织损伤,是人体的一种免疫保护机制。然而,肿瘤通过上调抑制性受体的表达,增强肿瘤微环境中的免疫抑制效应,造成效应T细胞衰竭,限制由CD4+和CD8+T细胞引发的抗肿瘤免疫反应,最终可能导致免疫逃逸或耐受。PD-L1是其中的一种抑制性受体,已被证实选择性表达于肿瘤部位,这种特点使“肿瘤靶向”免疫调节成为可能[34]。针对PD-1/PD-L1转导途径的免疫疗法通过阻止PD-1与PD-L1结合,释放T细胞的功能,恢复正常的免疫应答,并重新识别和攻击肿瘤细胞,达到抗肿瘤的效果。肿瘤上调PD-L1表达是逃脱免疫攻击,继而播散、复发、转移的重要方式,可能与肿瘤的不良预后相关。但是,现有的研究表明肿瘤组织中的PD-L1表达对结直肠癌的预后意义仍存在争议,因此,我们进行Meta分析来探讨使用PD-L1表达来预测CRC预后是否可行。

虽然已存在关于PD-L1与CRC预后关系的荟萃分析,但从纳入文献数量、分析模型及效应量选择等方面还有待商榷。Wu等[35]在2015年发表的关于PD-L1与人类实体瘤预后关系的Meta分析中,表明在CRC亚组中,PD-L1表达与5年OS下降有关,由于使用OR替代HR来评估肿瘤生存指标,且仅纳入2项研究,这可能会增加研究的偏倚。在另外3篇[36-38]有关的Meta分析中,PD-L1表达与CRC预后无统计学意义的关联。由于不是针对性研究CRC,存在相关纳入研究数量较少的特点。

本研究的预后分析结果显示PD-L1表达与OS和RFS下降相关。相关临床病理参数分析结果显示PD-L1的表达水平与肿瘤分化和淋巴结转移相关,而肿瘤分化差与淋巴结转移是CRC不良预后的危险因素。这些证据都支持PD-L1阳性表达与CRC更短的生存相关,可作为CRC的预后预测因子。亚组分析结果显示肿瘤细胞中PD-L1表达、多克隆抗体及单因素分析亚组与OS降低相关,且多克隆抗体及单因素分析亚组中异质性显著下降,由此推断抗体类型及HR评估类型可能是PD-L1表达与OS相关性分析中的主要异质性来源。而且,从亚组分析结果分析,肿瘤细胞中PD-L1与肿瘤浸润免疫细胞中PD-L1表达与OS及RFS的关系是不一致的,仅前者与不良的OS及RFS有统计学意义的关联。

事实上,在肿瘤组织中,PD-L1可表达于肿瘤细胞和肿瘤浸润性免疫细胞(tumor infiltrating immune cells, TILs)中[39]。TILs的产生是一种适应性免疫反应,它在控制人类肿瘤生长和复发中的作用存在争议[40]。有研究表明TILs可以促进肿瘤的免疫逃逸和转移[41-42]。此外,TILs虽然在体外具有增殖和清除肿瘤细胞的作用,但在体内,由于肿瘤微环境中存在免疫抑制性骨髓细胞和免疫检查点分子上调所形成的免疫抑制性微环境,使得T细胞难以发挥其作用[43-44]。本研究的分析结果显示肿瘤细胞与TILs中的PD-L1表达对CRC预后的影响存在不一致性,但限于纳入的关于TILs的研究较少,对此结果还需谨慎对待,需要更多的设计良好的队列研究来论证肿瘤浸润免疫细胞中的PD-L1表达对CRC预后的影响。

与以往的Meta分析相比,本研究存在以下优势:(1)纳入研究及样本量大,增加了Meta分析的检验效能;(2)探究了肿瘤细胞与肿瘤浸润性免疫细胞中PD-L1表达对CRC预后影响的异同;(3)数据由纳入文献直接给出,而非从生存曲线中提取,减小了误差;(4)敏感度分析证明了结果的稳定性。这些特点增加了此Meta分析结果的可信度。尽管如此,我们的研究仍存在不足:(1)各纳入研究进行免疫组织化学所使用的抗体类型存在不同,判断PD-L1阳性的截断值(cut-off value)标准多样(见表 1),没有对截断值进行亚组分析是本文的缺憾之处,这可能会增加研究的偏倚;(2)不同分子表型的CRC对免疫治疗的反应不一。由于缺乏原始研究数据的支持,此Meta分析未对不同分子表型进行亚组分析。

综上所述,肿瘤组织中PD-L1表达与CRC较短的OS及RFS、肿瘤分化和淋巴结转移有关,肿瘤细胞与肿瘤浸润性免疫细胞中的PD-L1表达对CRC预后的预测意义可能不一致。

作者贡献

饶雄辉:选题、筛选文献、数据提取与处理、书写全文

罗洪亮:筛选文献、数据提取及处理

黄俊、朱正明:提供建议,与团队商讨文献筛选及数据处理等问题

| [1] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(1): 7-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21387 |

| [2] |

Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality[J]. Gut, 2017, 66(4): 683-691. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912 |

| [3] |

Nappi A, Berretta M, Romano C, et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: role of target therapies and future perspectives[J]. Curr Cancer Drug Targets, 2018, 18(5): 421-429. DOI:10.2174/1568009617666170209095143 |

| [4] |

Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(10): 2479-2516. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mds236 |

| [5] |

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2016, 27(8): 1386-1422. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdw235 |

| [6] |

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(26): 2443-2454. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 |

| [7] |

Yang Y. Cancer immunotherapy: harnessing the immune system to battle cancer[J]. J Clin Invest, 2015, 125(9): 3335-3337. DOI:10.1172/JCI83871 |

| [8] |

McDermott DF, Atkins MB. PD-1 as a potential target in cancer therapy[J]. Cancer Med, 2013, 2(5): 662-673. |

| [9] |

Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2016, 8(328): 328r. |

| [10] |

Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2012, 12(4): 252-264. DOI:10.1038/nrc3239 |

| [11] |

Sanmamed MF, Chen L. Inducible expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1) and its selective role in tumor site immune modulation[J]. Cancer J, 2014, 20(4): 256-261. DOI:10.1097/PPO.0000000000000061 |

| [12] |

Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2015, 33(17): 1974-1982. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358 |

| [13] |

Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death[J]. EMBO J, 1992, 11(11): 3887-3895. DOI:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x |

| [14] |

Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the Pd-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel b7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation[J]. J Exp Med, 2000, 192(7): 1027-1034. DOI:10.1084/jem.192.7.1027 |

| [15] |

Shi SJ, Wang LJ, Wang GD, et al. B7-H1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal carcinoma and regulates the proliferation and invasion of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(10): e76012. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0076012 |

| [16] |

Song M, Chen D, Lu B, et al. PTEN loss increases PD-L1 protein expression and affects the correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical parameters in colorectal cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e65821. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0065821 |

| [17] |

Saigusa S, Toiyama Y, Tanaka K, et al. Implication of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in tumor recurrence and prognosis in rectal cancer with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy[J]. Int J Clin Oncol, 2016, 21(5): 946-952. DOI:10.1007/s10147-016-0962-4 |

| [18] |

Liang M, Li J, Wang D, et al. T-cell infiltration and expressions of T lymphocyte co-inhibitory B7-H1 and B7-H4 molecules among colorectal cancer patients in northeast China's Heilongjiang province[J]. Tumor Biol, 2014, 35(1): 55-60. |

| [19] |

Liu R, Peng K, Yu Y, et al. Prognostic value of immunoscore and pd-l1 expression in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with different ras status after palliative operation[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2018, 2018: 5920608. |

| [20] |

Marisa L, Svrcek M, Collura A, et al. The balance between cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytes and immune checkpoint expression in the prognosis of colon tumors[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2018, 110(1). |

| [21] |

Lee LH, Cavalcanti MS, Segal NH, et al. Patterns and prognostic relevance of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in colorectal carcinoma[J]. Mod Pathol, 2016, 29(11): 1433-1442. DOI:10.1038/modpathol.2016.139 |

| [22] |

Wang L, Ren F, Wang Q, et al. Significance of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immunohistochemical expression in colorectal cancer[J]. Mol Diagn Ther, 2016, 20(2): 175-181. DOI:10.1007/s40291-016-0188-1 |

| [23] |

Koganemaru S, Inoshita N, Miura Y, et al. Prognostic value of programmed death-ligand 1 expression in patients with stage Ⅲcolorectal cancer[J]. Cancer Sci, 2017, 108(5): 853-858. DOI:10.1111/cas.13229 |

| [24] |

Wang L, Liu Z, Fisher KW, et al. Prognostic value of programmed death ligand 1, p53, and Ki-67 in patients with advanced-stage colorectal cancer[J]. Hum Pathol, 2018, 71: 20-29. DOI:10.1016/j.humpath.2017.07.014 |

| [25] |

Droeser RA, Hirt C, Viehl CT, et al. Clinical impact of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in colorectal cancer[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2013, 49(9): 2233-2242. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.015 |

| [26] |

Zhu H, Qin H, Huang Z, et al. Clinical significance of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma[J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2015, 8(8): 9351-9359. |

| [27] |

Li Y, Liang L, Dai W, et al. Prognostic impact of programed cell death-1 (PD-1) and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in cancer cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer[J]. Mol Cancer, 2016, 15(1): 55. DOI:10.1186/s12943-016-0539-x |

| [28] |

Lee KS, Kwak Y, Ahn S, et al. Prognostic implication of CD274 (PD-L1) protein expression in tumor-infiltrating immune cells for microsatellite unstable and stable colorectal cancer[J]. Cancer Immunol, Immunother, 2017, 66(7): 927-939. DOI:10.1007/s00262-017-1999-6 |

| [29] |

Lee SJ, Jun SY, Lee IH, et al. CD274, LAG3, and IDO1 expressions in tumor-infiltrating immune cells as prognostic biomarker for patients with MSI-high colon cancer[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2018, 144(6): 1005-1014. DOI:10.1007/s00432-018-2620-x |

| [30] |

Hamada T, Cao Y, Qian ZR, et al. Aspirin use and colorectal cancer survival according to tumor CD274 (Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1) expression status[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(16): 1836-1844. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.7547 |

| [31] |

Dunne PD, McArt DG, O'Reilly PG, et al. Immune-derived PD-L1 gene expression defines a subgroup of stage Ⅱ/Ⅲ colorectal cancer patients with favorable prognosis who may be harmed by adjuvant chemotherapy[J]. Cancer Immunol Res, 2016, 4(7): 582-591. DOI:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0302 |

| [32] |

D'Alterio C, Nasti G, Polimeno M, et al. CXCR4-CXCL12-CXCR7, TLR2-TLR4, and PD-1/PD-L1 in colorectal cancer liver metastases from neoadjuvant-treated patients[J]. Oncoimmunology, 2016, 5(12): e1254313. DOI:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1254313 |

| [33] |

Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey[J]. CMAJ, 2007, 176(8): 1091-1096. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.060410 |

| [34] |

Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(26): 2455-2465. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1200694 |

| [35] |

Wu P, Wu D, Li L, et al. PD-L1 and Survival in Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(6): e0131403. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0131403 |

| [36] |

Xiang X, Yu PC, Long D, et al. Prognostic value of PD -L1 expression in patients with primary solid tumors[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 9(4): 5058-5072. |

| [37] |

Pyo JS, Kang G, Kim JY. Prognostic role of PD-L1 in malignant solid tumors: a meta-analysis[J]. Int J Biol Markers, 2017, 32(1): e68-e74. DOI:10.5301/jbm.5000225 |

| [38] |

Dai C, Wang M, Lu J, et al. Prognostic and predictive values of PD-L1 expression in patients with digestive system cancer: a meta-analysis[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2017, 10: 3625-3634. DOI:10.2147/OTT.S138044 |

| [39] |

Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A, et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints[J]. Cancer Discov, 2015, 5(1): 43-51. |

| [40] |

Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome[J]. Science, 2006, 313(5795): 1960-1964. DOI:10.1126/science.1129139 |

| [41] |

Di Caro G, Marchesi F, Laghi L, et al. Immune cells: plastic players along colorectal cancer progression[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2013, 17(9): 1088-1095. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.12117 |

| [42] |

Giraldo NA, Becht E, Remark R, et al. The immune contexture of primary and metastatic human tumours[J]. Curr Opin Immunol, 2014, 27: 8-15. DOI:10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.001 |

| [43] |

Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape[J]. Nat Immunol, 2002, 3(11): 991-998. DOI:10.1038/ni1102-991 |

| [44] |

Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K. Cancer immunoediting from immune surveillance to immune escape[J]. Immunology, 2007, 121(1): 1-14. |

2019, Vol. 46

2019, Vol. 46