文章信息

- 术前血液学炎性反应标志物在胶质瘤患者预后中的价值

- Predictive Value of Preoperative Hematologic Inflammatory Markers in Prognostic of Glioma Patients

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2019, 46(8): 714-719

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2019, 46(8): 714-719

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2019.19.0163

- 收稿日期: 2019-02-15

- 修回日期: 2019-05-13

胶质瘤约占中枢神经系统恶性肿瘤的35.26%~60.96%(平均44.69%),死亡率在癌症死亡排名中位居第二[1]。胶质瘤具有高度侵袭性,故其有复发率高、治愈率低、死亡率高的特点[2-3]。根据WHO分类,胶质瘤分为四个组织病理学分级(Ⅰ~Ⅳ),其中胶质母细胞瘤(glioblastoma, GBM, WHO Ⅳ级)患者预后最差,中位生存期仅为14.6月[4-5]。

研究表明,全身炎性反应相关的术前血液学标志物是癌症可靠的预测因子,如中性粒细胞与淋巴细胞比率(neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NLR)、单核细胞与淋巴细胞比率(monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, MLR)和血小板与淋巴细胞比率(platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR)升高与胃癌、肾癌、乳腺癌和肺癌等不良预后相关[6-7]。然而,仅少数研究报道上述术前血液学标志物对胶质瘤预后的意义。

本研究通过探讨炎性标志物对接受手术的胶质瘤患者预后的影响,对生存风险较高的患者进行分层,从而指导临床治疗。

1 资料与方法 1.1 临床资料本研究共纳入2013年1月—2018年1月就诊于天津医科大学肿瘤医院的180例患者。其中男104例,女76例;年龄3~77岁,平均年龄(50.11±16.13)岁;按WHO胶质瘤分类标准,Ⅰ~Ⅲ级患者88例,Ⅳ级患者92例;手术完全切除者154例,部分或不全切除者26例;手术完全切除的154例患者中,< 1年复发者70例,≥1年复发者84例。

1.2 纳入及排除标准纳入标准:均经我院病理科证实为胶质瘤者:按2007年WHO标准对肿瘤进行分类;既往无抗肿瘤治疗患者,包括手术切除及放化疗。

排除标准:有其他恶性肿瘤病史者;有急性或慢性炎性反应性疾病患者;患有糖尿病、心脏病、高血压、甲状腺功能异常或自身免疫性疾病者;近6月有类固醇治疗的患者;相关病例及随访资料不全者。

1.3 数据收集和定义对入组患者采取术前晨起空腹外周静脉血样,使用自动血液分析仪(Abbott CD-1800; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA)测量分析血液中中性粒细胞、单核细胞、淋巴细胞和血小板计数。

1.4 随访及评价指标入组患者通过门诊或电话进行随访,术后2年内每3月随访一次,术后第3~5年每6月随访一次,之后每年随访一次至死亡。本研究患者生存终点为肿瘤致死或末次随访时间,末次随访时间截至2019年1月14日。

患者复发依据标准为二次手术后病理学诊断结果,若未手术,依据临床症状及影像学诊断确认。总生存时间(OS)定义为患者自术后第一天开始至死亡或末次随访的时间。

1.5 统计学方法采用SPSS19.0统计学软件进行数据分析。通过ROC曲线计算Youden index(敏感度-(1-特异性))确定NLR、MLR、PLR的最佳分界值。计数资料描述采用例数表示,其组间比较采用χ2检验。应用Kaplan-Meier方法进行复发及生存分析,并通过Log rank检验进行比较。使用Cox比例风险模型进行多变量分析,发现影响预后的独立危险因素。Pearson's相关系数检验发现NLR与MLR和PLR的相关性。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

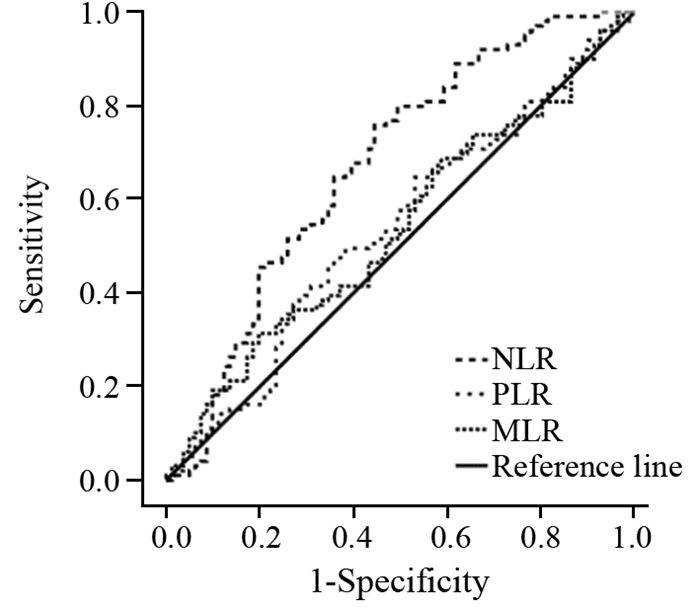

2 结果 2.1 NLR、MLR和PLR的最佳分界值患者NLR的ROC曲线下面积为0.673(P < 0.001)。NLR的最佳分界值为1.90(敏感度为75.8%,特异性为55.6%),故NLR≥1.90的患者为高NLR组,而NLR < 1.90为低NLR组。MLR和PLR的ROC曲线下面积分别为0.538(P=0.377)和0.538(P=0.384),MLR和PLR的最佳分界值分别为0.33(敏感度为31.3%,特异性为80.2%)和133.38(敏感度47.5%,特异性64.2%),以此最佳分界值分别定义高、低MLR和PLR组,见图 1。

|

| NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MLR: monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio 图 1 依据ROC曲线确定NLR、MLR和PLR的最佳分界值 Figure 1 Optimal cutoff values of NLR, MLR and PLR defined by ROC curves |

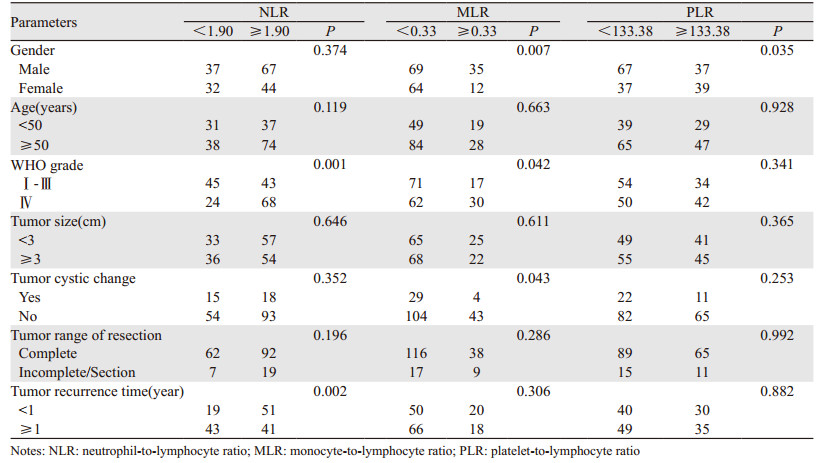

在180例胶质瘤患者中,57.8%为男性,42.2%为女性;62.2%的患者年龄≥50岁;WHOⅣ级GBM患者占51.1%;50%患者肿瘤直径≥3 cm;18.3%的患者肿瘤有囊变。NLR组在WHO分级中,差异有统计学意义(P=0.001),见表 1。

|

154例手术完全切除者中,复发时间 < 1年者占45.5%,其中低NLR组 < 1年复发率为30.6%,高NLR组为55.4%。对比MLR和PLR组,且仅NLR组在肿瘤复发时间中,差异有统计学意义(P=0.002),见表 1。

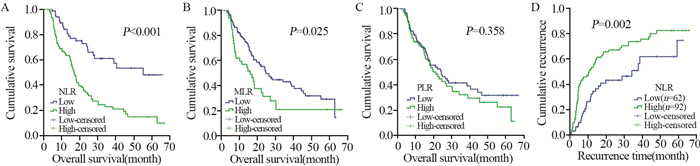

2.3 术前NLR、MLR和PLR与OS和肿瘤复发的关系根据Kaplan-Meier曲线,高NLR组的中位生存期为16.8月,低NLR组为40.5月;高MLR组中位生存期为14.8月,低MLR组为24.6月,差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。而高PLR组的中位生存期为19.7月,低PLR组中为23.9月,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见图 2A~C、表 2。

|

| 图 2 术前NLR(A)、MLR(B)和PLR(C)与患者生存率及术前NLR与患者术后复发率(D)的关系 Figure 2 Correlation between pre-operative NLR(A), MLR(B), PLR(C) and survival rate, between pre-operative NLR(D) and recurrence rate of glioma patients |

|

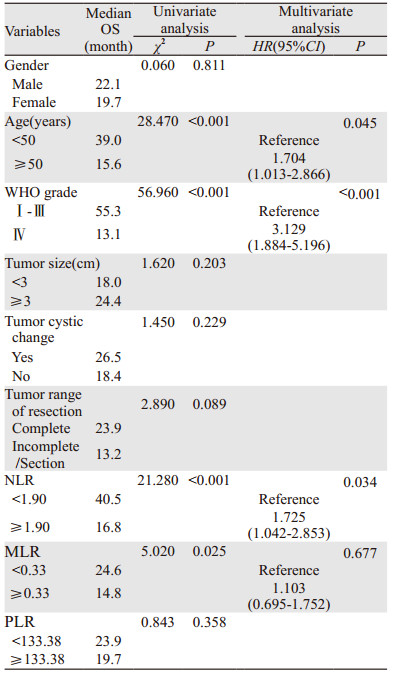

使用Cox比例风险模型进行多因素分析,在单因素分析中,年龄(P < 0.001)、肿瘤级别(P < 0.001)、NLR(P < 0.001)和MLR(P=0.025)与OS相关。而PLR(P=0.358)与OS在统计学上无显著相关性(P=0.108)。经多因素分析显示,三个术前血液学炎性反应标志物中,NLR是胶质瘤患者的独立预后标志物(HR=1.725; 95%CI: 1.042~2.853; P=0.034),见表 2。

根据Kaplan-Meier曲线,高NLR组中位肿瘤复发时间为10.3月,低NLR组为28.8月,差异有统计学意义(P=0.002),见图 2D。

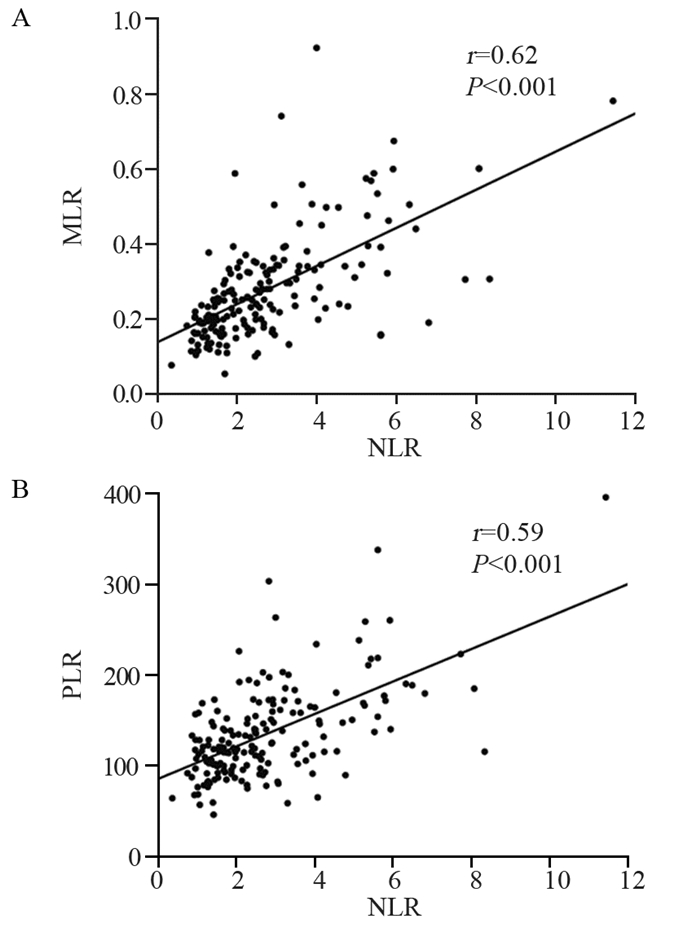

2.4 NLR与其他炎性反应标志物之间的关系经Pearson's相关系数检验发现,NLR与MLR(r=0.62, P < 0.001)及NLR与PLR(r=0.59, P < 0.001)之间均有正相关关系,差异有统计学意义,见图 3。

|

| 图 3 NLR与MLR(A)和PLR(B)之间的相关性 Figure 3 Correlation of NLR with MLR(A) and PLR(B) |

胶质瘤是颅内最常见的原发性恶性肿瘤,因具有高度侵袭性,即便手术切除并辅助放化疗,肿瘤复发率仍很高,患者预后较差[8-9]。虽然胶质瘤在全身肿瘤中发病率较低,但患者的死亡率极高[1],更需要预后相关分子的研究。最新肿瘤分类依据病理特征和分子标记,辅助患者治疗及预后预测。但分子诊断费用昂贵,不具有普遍易行性。因此,廉价且易于实行的系统性炎性反应标志物更具吸引力。

癌症相关的炎性反应已经成为恶性肿瘤的新标志[10],炎性反应状态和炎性反应微环境的变化与肿瘤的发生、发展相关。炎性反应细胞在肿瘤微环境内产生的细胞因子,包括促炎细胞因子、生长因子和趋化因子,可直接导致恶性肿瘤的进展[11-12]。肿瘤微环境也产生炎性反应介质,参与肿瘤细胞凋亡、血管生成和DNA损伤[13-14]。研究显示炎性反应诱导的转录因子的激活有助于神经胶质瘤细胞的存活和快速生长[15]。血液学炎性反应标志物是指外周血中参数,如C-反应蛋白、红细胞沉降率、NLR、PLR、MLR和RDW[13, 16]。与许多其他炎性反应标志物不同,NLR、PLR和MLR可以通过白细胞计数轻松计算。

本研究中,NLR在患者WHO分级中差异有统计学意义,这与已有研究报道的炎性反应标志物作为胶质瘤分级的诊断指标是一致的[17],而且胶质瘤的生存预后与肿瘤级别密切相关[18]。本研究显示术前NLR和MLR升高与患者不良预后显著相关,并且NLR是胶质瘤患者预后的独立危险因素。这与其他肿瘤中研究结果一致,高NLR与肿瘤的死亡率增加有关。一项胃癌患者的回顾性数据分析显示,高NLR患者的5年生存率明显低于NLR组的患者[19];有研究报道,乳腺癌患者NLR高的生存期明显较短[20];另有研究显示,在转移性黑色素瘤患者中,NLR与ipilimumab治疗患者的预后显著相关[21]。一些研究证明NLR是全身炎性反应的可靠指标。与淋巴细胞计数相比,NLR更能反映中性粒细胞计数对感染和炎性反应等压力的反应。NLR增高反映了淋巴细胞的相对耗尽,即免疫细胞的溶解活性降低,导致抗肿瘤免疫反应减弱[22]。此外,减弱的抗肿瘤免疫反应可促进肿瘤进展,这可能是患者预后较差的原因。且研究发现中性粒细胞可诱导神经胶质瘤患者免疫抑制和肿瘤血管生成,从而促进胶质瘤进展[23]。血小板介导的炎性反应有助于癌症进展,且研究者已在多种癌症中测试了各种基于血小板的炎性标志物[24]。在GBM患者中,血小板可诱导肿瘤血管生成和血管内皮生长因子的分泌,促进肿瘤进展。血小板源性生长因子亦有助于肿瘤发生[25]。然而,本研究未能确定PLR与胶质瘤患者生存预后的关系。这可能与本研究样本量小等有关。本研究单因素分析显示,MLR与患者不良预后相关,这与单核细胞可能通过产生炎性因子如肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)、IL-1和IL-6直接刺激肿瘤细胞生长研究一致[26],然而,在多变量分析中,其不是胶质瘤的独立预后标志物。为探索MLR和PLR是否与NLR有潜在关系,分析显示PLR和MLR与NLR有显著相关性,可为胶质瘤患者术前评估提供理论参考。据研究报道,肿瘤相关的炎性反应可导致血液成分如血小板、淋巴细胞和中性粒细胞的变化[27],如肿瘤细胞释放的炎性因子(例如IL-3、IL-6和IL-10)可刺激巨核细胞增殖并产生血小板[28-29],这可能与本研究中的相关性结果有关。这也与单核细胞计数可作为化疗后中性粒细胞数量变化的预测因子的研究一致[30]。

本研究发现,高NLR胶质瘤患者术后一年内复发率显著高于低NLR组,且整体肿瘤复发率亦高于低NLR组,而术后复发的胶质瘤患者生存预后更差。NLR与胶质瘤复发的关系研究甚少,但与胶质瘤患者术后与肿瘤复发机制的研究一致,作为局部侵袭性癌症,在约90%的患者中,肿瘤复发发生在肿瘤切除的边缘[31],手术脑损伤对胶质瘤复发的影响,包括多种分泌的生长因子、细胞因子和转录因子,可激活增殖和抗凋亡基因以及促进血管生成和炎性反应过程[32]。故高NLR促进胶质瘤患者术后复发的机制有待进一步探讨。

本研究系统地评估了常见的术前血液炎性反应标志物(即NLR、MLR和PLR)与所有胶质瘤组织学类型患者生存预后的结果,并探讨了其与肿瘤复发的关系。然而,由于是回顾性、单中心设计,患者数量有限,故本研究存在局限性。因此,需要前瞻性、多中心研究进一步验证我们的结论。

总之,以上研究表明,NLR与胶质瘤患者的预后密切相关,并且比其他血液炎性标志物更佳,是胶质瘤患者生存预后的独立危险因素。考虑到成本效益和易行性,NLR可以作为预测胶质瘤患者预后的生物标志物。并可为临床医师对胶质瘤患者进行危险分层提供理论依据,以便个体化治疗计划的实施及制定更有益的随访策略。

作者贡献

于雪迪:数据整理、分析和论文撰写

佘春华:论文设计

孙增峰:统计学分析指导

刘敬敬:临床病例收集

马莉:论文修订

李文良:论文指导

| [1] | Yi GQ, Gu B, Chen LK. The safety and efficacy of magnetic nano-iron hyperthermia therapy on rat brain glioma[J]. Tumour Biol, 2014, 35(3): 2445–2449. |

| [2] | Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2009-2013[J]. Neuro Oncol, 2016, 18(suppl_5): V1–V75. DOI:10.1093/neuonc/now207 |

| [3] | Angelopoulou E, Piperi C. Emerging role of plexins signaling in glioma progression and therapy[J]. Cancer Lett, 2018, 414: 81–87. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.010 |

| [4] | Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary[J]. Acta Neuropathol, 2016, 131(6): 803–820. DOI:10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 |

| [5] | Shi J, Hou S, Huang J, et al. An MSN-PEG-IP drug delivery system and IL13Rα2 as targeted therapy for glioma[J]. Nanoscale, 2017, 9(26): 8970–8981. DOI:10.1039/C6NR08786H |

| [6] | Fuentes HE, Oramas DM, Paz LH, et al. Venous Thromboembolism Is an Independent Predictor of Mortality Among Patients with Gastric Cancer[J]. J Gastrointest Cancer, 2018, 49(4): 415–421. DOI:10.1007/s12029-017-9981-2 |

| [7] | Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2014, 106(6): dju124. |

| [8] | Reni M, Mazza E, Zanon S, et al. Central nervous system gliomas[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2017, 113: 213–234. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.021 |

| [9] | Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, et al. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(26): 2499–2508. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1407279 |

| [10] | Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer[J]. Cell, 2010, 140(6): 883–899. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 |

| [11] | Jin X, Kim SH, Jeon HM, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 7 regulates glioma stem cells via interleukin-6 and Notch signaling[J]. Brain, 2012, 135(Pt4): 1055–1069. |

| [12] | Khan AA, Akritidis G, Pring T, et al. The Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Marker of Lymph Node Status in Patients with Rectal Cancer[J]. Oncology, 2016, 91(2): 69–77. DOI:10.1159/000443504 |

| [13] | Hu H, Yao X, Xie X, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative NLR, dNLR, PLR and CRP in surgical renal cell carcinoma patients[J]. World J Urol, 2017, 35(2): 261–270. DOI:10.1007/s00345-016-1864-9 |

| [14] | Müller I, Munder M, Kropf P, et al. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and T lymphocytes: strange bedfellows or brothers in arms[J]. Trends Immunol, 2009, 30(11): 522–530. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2009.07.007 |

| [15] | Michelson N, Rincon-Torroella J, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, et al. Exploring the role of inflammation in the malignant transformation of low-grade gliomas[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 2016, 297: 132–140. DOI:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.05.019 |

| [16] | Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2013, 88(1): 218–230. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010 |

| [17] | Weng W, Chen X, Gong S, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio correlated with glioma grading and glioblastoma survival[J]. Neurol Res, 2018, 40(11): 917–922. DOI:10.1080/01616412.2018.1497271 |

| [18] | Server A, Kulle B, Gadmar ØB, et al. Measurements of diagnostic examination performance using quantitative apparent diffusion coefficient and proton MR spectroscopic imaging in the preoperative evaluation of tumor grade in cerebral gliomas[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2011, 80(2): 462–470. |

| [19] | Shimada H, Takiguchi N, Kainuma O, et al. High preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts poor survival in patients with gastric cancer[J]. Gastric Cancer, 2010, 13(3): 170–176. DOI:10.1007/s10120-010-0554-3 |

| [20] | Chen J, Deng Q, Pan Y, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in breast cancer[J]. FEBS Open Bio, 2015, 5: 502–507. DOI:10.1016/j.fob.2015.05.003 |

| [21] | Ferrucci PF, Ascierto PA, Pigozzo J, et al. Baseline neutrophils and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: prognostic relevance in metastatic melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab[J]. Ann Oncol, 2018, 29(2): 524. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdx059 |

| [22] | el-Hag A, Clark RA. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system[J]. J Immunol, 1987, 139(7): 2406–2413. |

| [23] | Massara M, Persico P, Bonavita O, et al. Neutrophils in Gliomas[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1349. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01349 |

| [24] | Bambace NM, Holmes CE. The platelet contribution to cancer progression[J]. J Thromb Haemost, 2011, 9(2): 237–249. |

| [25] | Di Vito C, Navone SE, Marfia G, et al. Platelets from glioblastoma patients promote angiogenesis of tumor endothelial cells and exhibit increased VEGF content and release[J]. Platelets, 2017, 28(6): 585–594. DOI:10.1080/09537104.2016.1247208 |

| [26] | Lindholm PF, Sivapurapu N, Jovanovic B, et al. Monocyte-Induced Prostate Cancer Cell Invasion is Mediated by Chemokine ligand 2 and Nuclear Factor-κB Activity[J]. J Clin Cell Immunol, 2015, 6(2): pii: 308. |

| [27] | Feng JF, Huang Y, Liu JS. Combination of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio is a useful predictor of postoperative survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2013, 6: 1605–1612. |

| [28] | Alexandrakis MG, Passam FH, Moschandrea IA, et al. Levels of serum cytokines and acute phase proteins in patients with essential and cancer-related thrombocytosis[J]. Am J Clin Oncol, 2003, 26(2): 135–140. DOI:10.1097/01.COC.0000017093.79897.DE |

| [29] | Klinger MH, Jelkmann W. Role of blood platelets in infection and inflammation[J]. J Interferon Cytokine Res, 2002, 22(9): 913–922. DOI:10.1089/10799900260286623 |

| [30] | Ouyang W, Liu Y, Deng D, et al. The change in peripheral blood monocyte count: A predictor to make the management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia[J]. J Cancer Res Ther, 2018, 14(Supplement): S565–S570. |

| [31] | Lemée JM, Clavreul A, Menei P. Intratumoral heterogeneity in glioblastoma: don't forget the peritumoral brain zone[J]. Neuro Oncol, 2015, 17(10): 1322–1332. DOI:10.1093/neuonc/nov119 |

| [32] | Hamard L, Ratel D, Selek L, et al. The brain tissue response to surgical injury and its possible contribution to glioma recurrence[J]. J Neurooncol, 2016, 128(1): 1–8. DOI:10.1007/s11060-016-2096-y |

2019, Vol. 46

2019, Vol. 46