文章信息

- 谷氨酰胺转运载体ASCT2在肿瘤中的研究进展

- Research Progress of Glutamine Transporter ASCT2 in Cancer

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2019, 46(3): 266-270

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2019, 46(3): 266-270

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2019.18.1149

- 收稿日期: 2018-08-15

- 修回日期: 2018-12-11

肿瘤细胞的生长需要大量能量,还原力,及合成高分子所必需的前体物质[1]。谷氨酰胺是人体血浆中含量最丰富的游离氨基酸,它与葡萄糖联合能够最大程度地满足肿瘤细胞在合成代谢中对能量和中间产物的需求[2]。此外,它还参与了肿瘤细胞增殖生长、氧化应激、信号转导等生理过程中的多条信号通路[3]。能够通过细胞膜转运谷氨酰胺的主要有四种溶质载体家族:溶质载体家族1(solute carrier family 1, SLC1)、溶质载体家族6(solute carrier family 6, SLC6)、溶质载体家族7(solute carrier family 7, SLC7)、溶质载体家族38(solute carrier family 38, SLC38)。ASCT2属于溶质载体家族1成员5(solute carrier family 1 member 5, SLC1A5),他是谷氨酰胺最重要的转运载体之一[4]。鉴于谷氨酰胺在生理和肿瘤中的重要作用,因此将谷氨酰胺的转运代谢作为治疗靶标具有巨大的潜力[5]。但目前国内对谷氨酰胺转运载体的相关报道较少,故本文对ASCT2的结构、生理特性、代谢调节、肿瘤治疗等方面作一综述。

1 ASCT2的结构与生理功能ASCT2属于丙氨酸-丝氨酸-半胱氨酸转运载体家族,ASCT家族包括ASCT1(SLC1A4)和ASCT2(SLC1A5)[6]。ASCT2蛋白在人的肺、骨骼肌、大肠、肾脏、睾丸和脂肪组织中均有表达。人类的ASCT2是一个由541个氨基酸组成的相对分子质量大约为56 598的膜蛋白,由SLC1A5基因编码,其基因定位于人的第19号染色体q臂13.3区。ASCT2高亲和力的转运底物有:L-Ala、L-Ser、L-Cys、L-Thr和L-Gln,ASCT2根据这些氨基酸在细胞内的浓度梯度决定谷氨酰胺是转入还是转出,此外还可以转运一些亲和力较低的中性氨基酸和谷氨酸盐,低pH值能促进ASCT2对谷氨酰胺的转运[7]。结构上,ASCT2是一个同型三聚体,其每个原体都含有一个支架区域(TMs 1,2,4,5)和一个转运区域(TMs 3,6,7,8),以及两个关键的螺旋发夹结构域:HP1和HP2。HP2跨膜位于转运区域,一端位于胞外,一端则处于细胞质中,HP1则完全处于细胞质中,HP1和HP2可能是ASCT2发挥转运功能的重要门控区域[8]。ASCT2第467位半胱氨酸决定了其只选择中性氨基酸作为底物的特性,而第481位的丝氨酸和482位的半胱氨酸则是它区别于ASCT1,能与谷氨酰胺结合的关键氨基酸[9]。

2 ASCT2与肿瘤谷氨酰胺对肿瘤细胞的增殖生长非常重要,它主要由ASCT2等转运载体输送到细胞中,而ASCT2在肿瘤中表达经常上调,包括多种实体瘤与血液肿瘤,其在肿瘤中的作用已经成为研究热点之一。

2.1 ASCT2与实体瘤 2.1.1 ASCT2与前列腺癌ASCT2在正常前列腺和前列腺肿瘤中均有表达,但其在前列腺癌中异常高表达。在前列腺癌细胞系LNCaP、PC-3中添加ASCT2的竞争性抑制剂苄基丝氨酸(benzylserine, BenSer),发现细胞摄取谷氨酰胺的能力显著下降,进一步检测细胞周期蛋白CDK1、CDC20和UBE2C的表达水平,也呈下降趋势,表明抑制ASCT2会抑制谷氨酰胺的转运,进而抑制前列腺癌细胞的生长。谷氨酰胺还参与了mTORC1(mammalian target of rapamycin complex1)信号通路的活化,研究人员检测了mTORC1下游分子p70S6K的磷酸化水平,发现只有在PC-3细胞中是下降的,LNCaP细胞中却没有这种现象。这说明除了mTORC1以外,还存在其他机制调节前列腺癌细胞的生长。用shRNA敲低ASCT2在PC3细胞中的表达,敲低后细胞周期阻滞且细胞活力下降。在裸鼠上建立前列腺癌移植瘤模型,接种敲低ASCT2的PC-3细胞系的小鼠肿瘤体积明显小于对照组,且肿瘤转移率也更低[10]。

ASCT2的表达可以被多种转录因子调节,比如Rb/E2F[11]、雄激素受体3[12]和ATF4[13]等。ATF4转录因子的活化还与前列腺癌的转移有关,ATF4转录因子表达在转移后不依赖于雄激素的前列腺癌中显著上调[12],而敲低ASCT2却能使早期前列腺癌肝转移和肺转移的风险下降[10]。

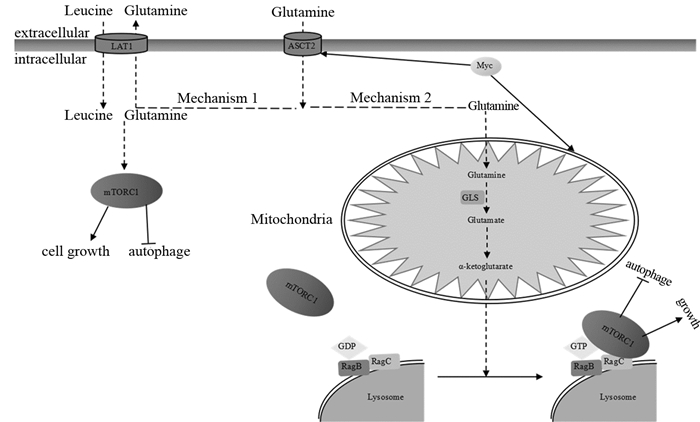

2.1.2 ASCT2与黑色素瘤在黑色素瘤细胞系C8161和1205Lu中用shRNA敲低ASCT2的表达,减少了谷氨酰胺和亮氨酸的转运量,从而可以抑制细胞的增殖和mTORC1的活化。用基因芯片技术分析ASCT2在正常皮肤组织和黑色素瘤中的表达水平,发现ASCT2在黑色素瘤中的表达水平升高了4.4倍,这说明ASCT2在黑色素瘤中有重要作用[14]。ASCT2调节mTORC1的活化并非依赖谷氨酰胺本身,而是ASCT2转运谷氨酰胺入胞,当胞内谷氨酰胺基础水平较高时,LAT1转运谷氨酰胺出胞的同时转运亮氨酸入胞这一动态过程[15]。此外,有文献报道了另一种谷氨酰胺活化mTORC1的机制,谷氨酰胺酶可以分解谷氨酰胺形成α-酮戊二酸盐,其参与三羧酸循环的过程也能激活Rag-mTORC1的信号通路,而不依赖于LAT1调节的亮氨酸转运的过程,见图 1。

ASCT2在结直肠癌中表达明显上调,免疫组织化学分析64例结直肠癌样本中ASCT2的表达情况,其中59%染色呈阳性,且表达水平与患者预后呈负相关[18]。统计分析90对样本的结直肠癌组织和临近的正常结直肠黏膜中ASCT2的表达水平,发现ASCT2在结直肠癌中的表达有明显上调。随机取出其中12对样本进行Western blot分析,同样能得出ASCT2在癌组织中过表达的结论[19]。此外,ASCT2在结直肠腺癌中的表达水平要显著高于黏液癌,这与此前报道的GLS1(谷氨酰胺分解过程中一种主要的酶)在腺癌而非黏液癌中过表达的结果一致,预示谷氨酰胺在腺癌中可能有不同于黏液癌的代谢途径[19-20]。

2.1.4 ASCT2与三阴性乳腺癌三阴性乳腺癌是雌激素受体、孕激素受体及人表皮生长因子受体2均阴性的乳腺癌患者,对这种乳腺癌没有相应的靶向疗法,只能依赖手术和放化疗进行治疗,其预后也较其他类型差[21]。有文献报道Basal-like型(即三阴性乳腺癌)相较于Luminal型乳腺癌,对谷氨酰胺的摄取更为敏感[22]。选择两株不同临床背景的乳腺癌细胞系MCF-7(Luminal型)和HCC1806(Basal-like型)进行研究,这两株细胞系均高表达ASCT2。用ASCT2的抑制剂GPNA处理两株细胞,只有HCC1806细胞的生长受到抑制,且mTORC1的活性降低,ASCT2受抑制使HCC1806发生凋亡的细胞明显增多,而MCF-7的细胞活力不受影响。这些事实表明不同乳腺癌细胞系对ASCT2活性的依赖程度不同,只有Basal-like型的乳腺癌细胞系生长需要ASCT2摄取谷氨酰胺[23]。因此,靶向ASCT2或者下游的谷氨酰胺代谢通路,可能成为治疗三阴性乳腺癌的新疗法[24]。

2.2 ASCT2与血液肿瘤在许多早期急性髓系白血病(acute myeloid leukemia, AML)的病例中,mTORC1处于活化的状态,但其具体活化机制未知[25]。氨基酸可以调节mTORC1的活性,主要是亮氨酸[26]。将亮氨酸转运到胞内的同时需要将谷氨酰胺转运到胞外,因此亮氨酸的转运效率取决于胞内谷氨酰胺的浓度,而谷氨酰胺的摄取主要依赖转运载体ASCT2[27],摄取谷氨酰胺入胞和随后流出胞外交换亮氨酸入胞这一过程已成为mTORC1活化的限速步骤[15]。对所有AML细胞系进行谷氨酰胺饥饿处理,发现p70S6K T389和4E-BP1 S65磷酸化水平降低,且24 h后所有细胞系都发生凋亡,其中现象最明显的是MV4-11和OCI-AML3细胞,这些结果预示着谷氨酰胺的剥夺会抑制mTORC1的活化,进一步诱导细胞凋亡[28]。ASCT2在所有白血病细胞系中都有表达,抑制ASCT2的表达可以诱导细胞凋亡,表现出抗癌活性。但完全抑制HL-60细胞中ASCT2的表达也没有引起细胞凋亡,这可能是因为有其他谷氨酰胺转运载体表达作为补偿,从而也能活化mTORC1[29]。

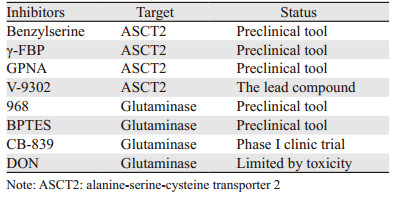

3 ASCT2与谷氨酰胺代谢的相关抑制剂鉴于谷氨酰胺在生理和肿瘤中的重要作用,将谷氨酰胺的转运代谢作为治疗靶标具有巨大的潜力。因此针对谷氨酰胺转运载体ASCT2和其代谢的关键酶谷氨酰胺酶,开发了多种抑制剂,部分抑制剂在前期研究中表现出良好的抗癌活性。

3.1 ASCT2的竞争性抑制剂Benzylserine和Benzylcysteine能通过竞争性结合ASCT2的底物结合位点,抑制ASCT2的功能。此外,这些化合物还可以抑制阴离子的电导率,而阴离子的电导性与转运底物的移动有关,因此这两个化合物能竞争性地阻断ASCT2转运底物的移位。由于Benzylserine和Benzylcysteine与ASCT2结合的亲和力仍然偏低,意味着在生理学研究中需要使用高浓度的抑制剂,这会导致与其他蛋白的非特异性作用增强。在化合物的丝氨酸或半胱氨酸残基上的β-碳上添加亲水羟基或酰胺基可能可以提高化合物与ASCT2的亲和力[30]。研究人员开发了一种与hASCT2有很强亲和力的竞争性拮抗剂-V-9302。V-9302保守的α-氨基酸头基与两性离子识别位点形成了关键的相互作用,两性离子识别位点也是ASCT2识别其他氨基酸及派生物的位点。经软件模拟V-9302能与hASCT2的氨基酸结合口袋兼容,且谷氨酰胺与hASCT2的结合区域与V-9302重叠。基于此,V-9302能特异性识别hASCT2并抑制其转运氨基酸的功能,尤其是谷氨酰胺的转运[5]。

3.2 ASCT2的共价抑制剂研究发现大鼠的ASCT2蛋白能与金属,比如汞及其有机派生物结合,这能抑制谷氨酰胺的转运,这种结合可能是由于大鼠的序列中有与金属结合的模体(CXXC)[31]。虽然人的ASCT2上没有CXXC模体,但它的半胱氨酸残基能与汞的派生物成键产生强反应性[32-33]。第467位的半胱氨酸残基被认为是hASCT2的底物结合位点的一部分,并且与谷氨酰胺的识别和移位有关。针对ASCT2上半胱氨酸残基开发抑制剂具有高特异性和高效力的优势,避免了底物类似物类抑制剂与ASCT2结合可能被浓度更高的内源性氨基酸替换的问题[34]。

3.3 ASCT2新型靶向抑制剂-脯氨酸派生物化合物γ-FBP是一种脯氨酸派生物,尽管脯氨酸并非ASCT2的转运底物,但γ-FBP具有抑制大鼠ASCT2转运的功能,在人的一些黑色素瘤细胞系上也能抑制ASCT2转运底物[35]。因此,针对hASCT2亚型设计脯氨酸派生物类分子是一种开发ASCT2抑制剂的新方法。

3.4 谷氨酰胺酶抑制剂肿瘤细胞对谷氨酰胺的消耗量相比正常细胞更高,这种代谢重编程常依赖于线粒体的谷氨酰胺酶的活性,它可以将谷氨酰胺转化为生物合成过程所需的关键前体物质-谷氨酸盐[36]。近年来针对这种关键酶设计了一些抑制剂,其中合成化合物CB-839已经进入治疗晚期实体瘤的一期临床试验,并表现出良好的治疗潜力[37]。一方面,肿瘤细胞对谷氨酰胺代谢的依赖性,使谷氨酰胺酶成为一种有潜力的抗癌靶点,但另一方面,谷氨酰胺酶亚细胞定位不明确,亚型较多,这可能会阻碍谷氨酰胺酶抑制剂的设计和药物的可获得性[35]。相关ASCT2和谷氨酰胺酶抑制剂总结,见表 1。

谷氨酰胺转运载体ASCT2在多种肿瘤细胞中过表达已经被充分证明,体内体外抑制ASCT2的表达都能起到抑制肿瘤细胞生长增殖的作用,直接抑制谷氨酰胺的代谢也能得到相似结果。这主要是过表达的ASCT2增强了对谷氨酰胺的转运,从而增强了mTORC1信号通路的活性,但其具体谷氨酰胺的转运调控机制未知。由于ASCT2膜蛋白的特性和谷氨酰胺转运功能,使其成为极具潜力的肿瘤治疗靶标,但目前进入临床肿瘤靶向治疗的抑制谷氨酰胺转运和代谢的药物还很少。2018年6月,研究人员成功解析了hASCT2 3.85?分辨率的冷冻电镜结构,发现了一些重要的结构域如转运门控区域HP2,以及通过定点突变发现第467位半胱氨酸是hASCT2与底物的关键结合位点[8]。针对这些结构和重要位点,结合分子生物学、结构生物学和氨基酸转运载体的动力学等手段,设计筛选ASCT2的特异性抑制剂,将成为未来开发靶向肿瘤代谢药物的研究热点之一。

作者贡献

王雅乐:搜集整理文献,初稿撰写,修改文章至定稿

黄承浩:承担课题经费,指导选题及稿件修改

| [1] | Levine AJ, Puzio-Kuter AM. The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes[J]. Science, 2010, 330(6009): 1340–4. DOI:10.1126/science.1193494 |

| [2] | DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q's next:the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer[J]. Oncogene, 2010, 29(3): 313–24. DOI:10.1038/onc.2009.358 |

| [3] | Shanware NP, Mullen AR, DeBerardinis RJ, et al. Glutamine:pleiotropic roles in tumor growth and stress resistance[J]. J Mol Med (Berl), 2011, 89(3): 229–36. DOI:10.1007/s00109-011-0731-9 |

| [4] | Bhutia YD, Ganapathy V. Glutamine transporters in mammalian cells and their functions in physiology and cancer[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2016, 1863(10): 2531–9. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.12.017 |

| [5] | Schulte ML, Fu A, Zhao P, et al. Pharmacological blockade of ASCT2-dependent glutamine transport leads to antitumor efficacy in preclinical models[J]. Nat Med, 2018, 24(2): 194–202. DOI:10.1038/nm.4464 |

| [6] | Kanai Y, Hediger MA. The glutamate/neutral amino acid transporter family SLC1:molecular, physiological and pharmacological aspects[J]. Pflugers Arch, 2004, 447(5): 469–79. DOI:10.1007/s00424-003-1146-4 |

| [7] | Utsunomiya-Tate N, Endou H, Kanai Y. Cloning and functional characterization of a system ASC-like Na+-dependent neutral amino acid transporter[J]. J Biol Chem, 1996, 271(25): 14883–90. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.25.14883 |

| [8] | Garaeva AA, Oostergete GT, Gati C, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2[J]. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2018, 25(6): 515–21. DOI:10.1038/s41594-018-0076-y |

| [9] | Scopelliti AJ, Font J, Vandenberg RJ, et al. Structural characterisation reveals insights into substrate recognition by the glutamine transporter ASCT2/SLC1A5[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 38. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02444-w |

| [10] | Wang Q, Hardie RA, Hoy AJ, et al. Targeting ASCT2-mediated glutamine uptake blocks prostate cancer growth and tumour development[J]. J Pathol, 2015, 236(3): 278–89. DOI:10.1002/path.4518 |

| [11] | Reynolds MR, Lane AN, Robertson B, et al. Control of glutamine metabolism by the tumor suppressor Rb[J]. Oncogene, 2014, 33(5): 556–66. DOI:10.1038/onc.2012.635 |

| [12] | Wang Q, Tiffen J, Bailey CG, et al. Targeting amino acid transport in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer:effects on cell cycle, cell growth, and tumor development[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2013, 105(19): 1463–73. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djt241 |

| [13] | Ren P, Yue M, Xiao D, et al. ATF4 and N-Myc coordinate glutamine metabolism in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells through ASCT2 activation[J]. J Pathol, 2015, 235(1): 90–100. DOI:10.1002/path.4429 |

| [14] | Wang Q, Beaumont KA, Otte NJ, et al. Targeting glutamine transport to suppress melanoma cell growth[J]. Int J Cancer, 2014, 135(5): 1060–71. DOI:10.1002/ijc.v135.5 |

| [15] | Nicklin P, Bergman P, Zhang B, et al. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy[J]. Cell, 2009, 136(3): 521–34. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044 |

| [16] | Duran RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, et al. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling[J]. Mol Cell, 2012, 47(3): 349–58. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.043 |

| [17] | Wise DR, Thompson CB. Glutamine addiction:a new therapeutic target in cancer[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2010, 35(8): 427–33. DOI:10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.003 |

| [18] | Witte D, Ali N, Carlson N, et al. Overexpression of the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human colorectal adenocarcinoma[J]. Anticancer Res, 2002, 22(5): 2555–7. |

| [19] | Huang F, Zhao Y, Zhao J, et al. Upregulated SLC1A5 promotes cell growth and survival in colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2014, 7(9): 6006–14. DOI:10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00410-0 |

| [20] | Huang F, Zhang Q, Ma H, et al. Expression of glutaminase is upregulated in colorectal cancer and of clinical significance[J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2014, 7(3): 1093–100. DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.3.1501 |

| [21] | Gluz O, Liedtke C, Gottschalk N, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer-current status and future directions[J]. Ann Oncol, 2009, 20(12): 1913–27. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdp492 |

| [22] | Kung HN, Marks JR, Chi JT. Glutamine synthetase is a genetic determinant of cell type-specific glutamine independence in breast epithelia[J]. PLoS Genet, 2011, 7(8): e1002229. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002229 |

| [23] | van Geldermalsen M, Wang Q, Nagarajah R, et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple-negative basal-like breast cancer[J]. Oncogene, 2016, 35(24): 3201–8. DOI:10.1038/onc.2015.381 |

| [24] | Gross MI, Demo SD, Dennison JB, et al. Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2014, 13(4): 890–901. DOI:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0870 |

| [25] | Avramis VI, Martin-Aragon S, Avramis EV, et al. Pharmacoanalytical assays of Erwinia asparaginase (erwinase) and pharmacokinetic results in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (HR ALL) patients:simulations of erwinase population PK-PD models[J]. Anticancer Res, 2007, 27(4C): 2561–72. |

| [26] | Avruch J, Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, et al. Amino acid regulation of TOR complex 1[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2009, 296(4): E592–602. DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.90645.2008 |

| [27] | Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer:partners in crime?[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2005, 15(4): 254–66. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005 |

| [28] | Willems L, Jacque N, Jacquel A, et al. Inhibiting glutamine uptake represents an attractive new strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia[J]. Blood, 2013, 122(20): 3521–32. DOI:10.1182/blood-2013-03-493163 |

| [29] | Pinilla J, Aledo JC, Cwiklinski E, et al. SNAT2 transceptor signalling via mTOR:a role in cell growth and proliferation?[J]. Front Biosci (Elite Ed), 2011, 3: 1289–99. DOI:10.2741/e332 |

| [30] | Grewer C, Grabsch E. New inhibitors for the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 reveal its Na+-dependent anion leak[J]. J Physiol, 2010, 557(Pt3): 747–59. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062521 |

| [31] | Oppedisano F, Galluccio M, Indiveri C. Inactivation by Hg2+ and methylmercury of the glutamine/amino acid transporter (ASCT2) reconstituted in liposomes:Prediction of the involvement of a CXXC motif by homology modelling[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2010, 80(8): 1266–73. DOI:10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.032 |

| [32] | Scalise M, Pochini L, Console L, et al. Cys site-directed mutagenesis of the human SLC1A5 (ASCT2) transporter:structure/function relationships and crucial role of Cys467 for redox sensing and glutamine transport[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(3): pii:E648. DOI:10.3390/ijms19030648 |

| [33] | Pingitore P, Pochini L, Scalise M, et al. Large scale production of the active human ASCT2 (SLC1A5) transporter in Pichia pastoris-functional and kinetic asymmetry revealed in proteoliposomes[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013, 1828(9): 2238–46. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.034 |

| [34] | Scalise M, Pochini L, Galluccio M, et al. Glutamine transport and mitochondrial metabolism in cancer cell growth[J]. Front Oncol, 2017, 7: 306. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2017.00306 |

| [35] | Claire C, Grewer C, Armanda Gameiro, et al. Ligand discovery for the alanine-serine-Cysteine transporter (ASCT2, SLC1A5) from homology modeling and virtual screening[J]. PLoS Comput Biol, 2015, 11(10): e1004477. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004477 |

| [36] | Katt WP, Lukey MJ, Cerione RA. A tale of two glutaminases:homologous enzymes with distinct roles in tumorigenesis[J]. Future Med Chem, 2017, 9(2): 223–43. DOI:10.4155/fmc-2016-0190 |

| [37] | Gross MI, Demo SD, Dennison JB, et al. Antitumor activity of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2014, 13(4): 890–901. DOI:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0870 |

2019, Vol. 46

2019, Vol. 46