文章信息

- 外周血循环肿瘤细胞对头颈恶性肿瘤患者临床病理特征和预后价值的Meta分析

- Clinicopathological and Prognostic Value of Circulating Tumor Cells in Peripheral Blood in Head and Neck Cancer Patients:A Meta-analysis

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2018, 45(11): 883-889

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2018, 45(11): 883-889

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2018.18.0407

- 收稿日期: 2018-03-26

- 修回日期: 2018-06-14

头颈恶性肿瘤作为人类常见的上皮性恶性肿瘤之一, 在所有恶性肿瘤中排第7位, 全球每年约有50万新发病例, 同时, 约35万人死于头颈恶性肿瘤[1]。近年来, 随着手术、放疗和化疗等多种治疗手段的不断进步和成熟, 头颈恶性肿瘤的治疗效果已得到一定改善, 但5年生存率仍仅约为40%~50%, 复发和转移仍是头颈恶性肿瘤患者死亡的首要原因[2]。研究表明, 约有50%的患者在手术切除原发肿瘤后会出现局部复发, 而高达25%的患者在经过积极治疗后会发生远处转移[2]。因此, 早期识别复发转移对改善头颈恶性肿瘤患者的预后具有重要意义。

新近提出的循环肿瘤细胞(circulating tumor cells, CTCs)检测为对早期发现肿瘤微转移、监测治疗疗效和评估患者预后提供了新的选择[3]。相关荟萃分析已证实了外周血CTCs检测在乳腺癌[4]、肺癌[5]、食管癌[6]、直肠癌[7]、胰腺癌[8]、卵巢癌[9]和前列腺癌[10]等多种恶性肿瘤中的预后评估价值, 然而, 其在头颈恶性肿瘤中的临床意义仍存在争议[11-15]。鉴于此, 本研究拟采用系统评价的方法, 对既往发表的相关研究结果进行汇总分析, 以综合评估外周血CTCs检测与头颈恶性肿瘤患者临床病理特征和预后之间的关系, 从而为头颈恶性肿瘤的疗效监测和预后评估提供参考。

1 资料与方法 1.1 文献检索利用计算机检索PubMed、Embase和Cochrane图书馆等外文数据库和中国生物医学文献数据库(CMB)、中国知网全文数据库(CNKI)和万方数据库等中文数据库, 检索时间为自建库至2018年3月, 并通过人工阅读检索参考文献以及应用谷歌学术(Google Scholar)辅以检索以避免漏检。文献检索采用主题词和自由词相结合的方法, 其中, 英文检索词为“head and neck cancer ”或“head and neck squamous cell carcinoma”或“HNSCC”和“circulating tumor cell”或“circulating tumor cells”或“CTC”或“CTCs”, 中文检索词为“头颈部肿瘤”或“头颈恶性肿瘤”或“头颈部鳞状细胞癌”和“循环肿瘤细胞”。

1.2 文献纳入与排除标准纳入标准:(1)研究类型为原创性研究, 文种限英文或中文; (2)研究对象均为经病理组织学证实为头颈恶性肿瘤的患者; (3)暴露因素为进行了外周血CTCs检测, 并分为阳性组和阴性组; (4)研究目的为研究CTCs与患者总生存期(OS)或无病生存期(DFS)或无进展生存期(PFS)或复发或临床病理特征之间的关系; (5)文献中有关于OS或DFS或PFS的预后风险比(hazard ratio, HR)和其95%可信区间(confidence intervals, CI)值或可从显示的数据中计算获得。

排除标准:(1)样本为非外周静脉血; (2)基于同一群患者的重复研究; (3)荟萃分析, 综述, 病例报告, 专家经验报告, 学位论文, 以及只有摘要而缺乏全文的文献。

1.3 文献筛选和资料提取由2名合格的评价员独立完成, 首先浏览所有初步检出文献的题名和摘要来筛查符合纳入标准的文献, 通过题名、摘要难以判断的则查阅全文核实, 原文未描述清楚的资料尽量与作者联系予以补充, 意见不一致时提交第三方协商解决。然后, 2名评价员采用统一的资料提取表进行资料提取, 提取的内容包括:(1)第一作者、出版年份、患者来源; (2)患者例数、肿瘤分期、CTCs阳性率、检测方法和采样率时间; (3)可直接或间接从文中得到的HR及其95%CI值。提取完成后, 双方交叉检查对方提取的信息, 有异议之处通过双方讨论或交由第三方裁定解决。若原文中没有直接提供关于预后指标的HR及95%CI值, 则根据Tierney等[16]提供的方法, 用Engauge Digitizer 4.1软件析出原始数据, 再经过推理得出, 意见不一致时则通过查阅原始资料核实。

1.4 纳入文献质量评价由2位研究者根据纽卡斯尔-渥太华量表(Newcastle-Ottawa scale, NOS)分别对纳入文献的质量进行评价。NOS量表满分为9分, 包括观察组和对照组研究对象的定义和选择、两组的可比性以及暴露因素3方面内容, 0~4分为低质量, 5~9分为高质量[17]。如遇分歧, 由2位研究者通过讨论或交由第三名研究者裁定解决。

1.5 统计学方法利用Stata12.0软件(Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA)进行统计分析。采用Q检验(检验水准为P=0.10)和I2检验(检验水准为I2=50%)进行异质性分析, 若P > 0.10且I2≤50%, 表明纳入研究将无明显异质性, 选用固定效应模型进行效应量合并; 反之, 则使用随机效应模型。预后资料采用HR作为效应量, 相对危险度(relative risk, RR)用来评估CTCs与复发和临床病理特征之间的相关性, 各效应均以95%CI表示, P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。敏感度分析用于进一步探究各项纳入研究对合并结果的影响。发表偏移的评估采用Begg’s检验, P < 0.05提示存在发表偏倚。

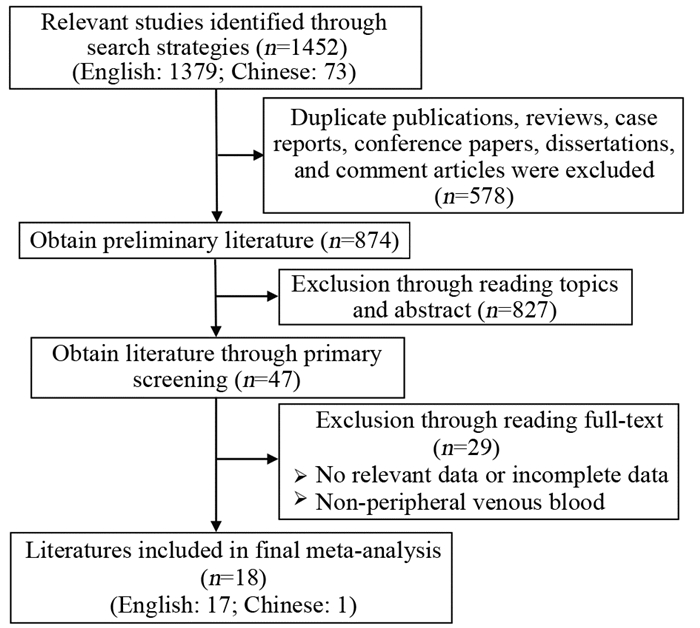

2 结果 2.1 纳入文献基本特征按照检索要求, 共检索到中英文文献1 452篇, 按纳入及排除标准进行筛选, 最终共有18篇文献(英文:17篇[11-15, 18-29]; 中文1篇[30])纳入Meta分析, 具体筛选过程见图 1。文献发表年限在2002年至2018年之间, 总计包含779例Ⅰ~Ⅳ期头颈恶性肿瘤患者, 各纳入文献的基本特征见表 1。按照NOS评分量表, 11篇文献为高质量[11-15, 20, 23, 25-28], 7篇为低质量[18-19, 21-22, 24, 29-30], 见表 1。

|

| 图 1 文献筛选流程图 Figure 1 Flow chart of included studies screening |

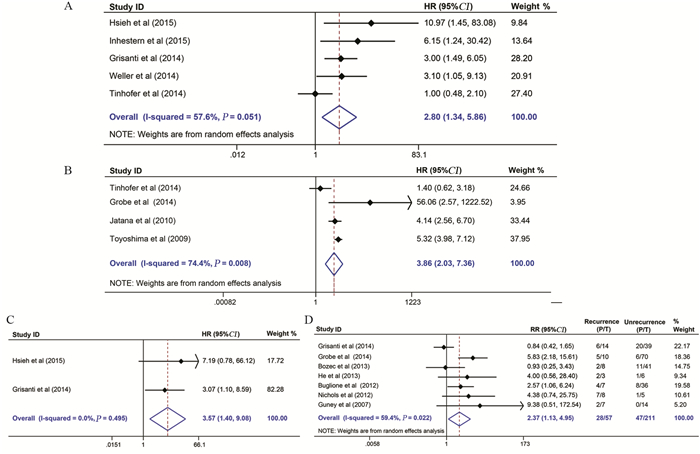

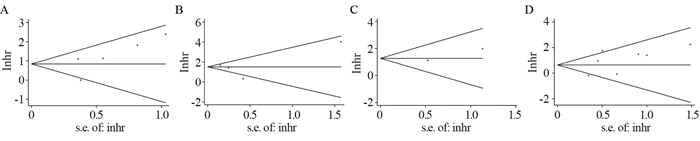

共有5项以OS为观察终点的纳入研究[11-15], 异质性检验提示各研究间存在中度异质性(I2=57.6%, P=0.051), 故采用随机效应模型进行分析。结果表明, 与CTCs阴性组相比, CTCs阳性组患者的OS明显缩短, 差异有统计学意义(HR=2.80, 95%CI:1.34~5.86, P=0.006), 见图 2A。

|

| A:overall survival (OS); B:disease-free survival (DFS); C:progression-free survival (PFS); D:recurrence 图 2 CTCs与头颈恶性肿瘤患者预后关系的Meta分析森林图 Figure 2 Meta-analysis of relationship between CTCs and prognosis of head and neck cancer patients |

共有4项以DFS为观察终点的纳入研究[15, 20, 26-27], 异质检验提示各研究间存在异质性(I2=74.4%, P=0.008), 故采用随机效应模型进行分析。结果表明, CTCs阳性组患者的DFS明显短于CTCs阴性组, 差异有统计学意义(HR=3.86, 95%CI:2.03~7.36, P < 0.001), 见图 2B。

2.2.3 无进展生存期(PFS)共有2项以PFS为观察终点的纳入研究[11, 13], 异质性检验提示各研究间同质性较好(I2=0.0%, P=0.495), 故采用固定效应模型进行分析。结果表明, CTCs阳性组患者的PFS也明显短于CTCs阴性组, 差异有统计学意义(HR=3.57, 95%CI:1.40~9.08, P=0.008), 见图 2C。

2.2.4 复发共有7项以复发为观察终点的纳入研究[13, 20-24, 28], 异质性检验提示各研究间存在中度异质性(I2=59.4%, P=0.022), 故采用随机效应模型进行分析。结果表明, CTCs阳性组患者的复发风险显著高于CTCs阴性组, 差异有统计学意义(RR=2.13, 95%CI:1.13~4.95, P=0.022), 见图 2D。

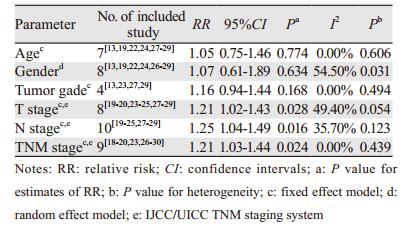

2.3 外周血CTCs与临床病理特征的相关性研究对外周血中CTCs与头颈恶性肿瘤关系密切的多种临床病理特征(包括年龄、性别、肿瘤组织学分级、T分期、N分期和TNM分期)之间的相关性进行了分析, 结果表明, 外周血中CTCs的检出与头颈恶性肿瘤的T分期(RR=1.21, 95%CI:1.02~1.43, P=0.028)、N分期(RR=1.25, 95%CI:1.04~1.49, P=0.016)和TNM分期(RR=1.21, 95%CI:1.03~1.44, P=0.024)呈显著正相关, 而与患者年龄(RR=1.05, 95%CI:0.75~1.46, P=0.774)、性别(RR=1.07, 95%CI:0.61~1.89, P=0.634)和肿瘤组织学分级(RR=1.16, 95%CI:0.94~1.44, P=0.168)均无相关性, 见表 2。

|

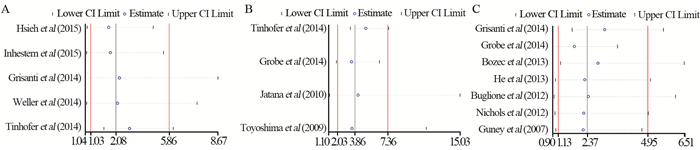

由上述研究结果可看出, OS、DFS和复发组纳入研究间存在相对明显的异质性, 但由于纳入研究数目均小于10项(OS:5; DFS:4;复发:7), 不推荐使用Meta回归分析以探索异质性的来源, 因此, 我们进行了敏感度分析去探究单个纳入研究对合并结果的影响。结果显示, 无论是对于OS、DFS还是复发, 汇总结果在省略任何一项纳入研究后均未发生明显变化, 均证实外周血CTCs阳性患者比CTCs阴性患者预后更差, 见图 3, 提示本研究结果稳定可靠, 可信度较高。

|

| A:overall survival (OS); B:disease-free survival (DFS); C:recurrence 图 3 CTCs与预后关系的敏感度分析 Figure 3 Sensitivity analysis of relationship between CTCs and prognosis of head and neck cancer patients |

对提供OS、DFS、PFS和复发数据的研究进行Begg’s检验发现, OS组(P=0.221)、DFS组(P=0.734)、PFS组(P=1.000)和复发组(P=0.368)纳入研究间大体呈对称均匀分布, 提示各研究没有明显的发表偏倚, 纳入研究具有良好的代表性, 见图 4。

|

| A:overall survival (OS); B:disease-free survival (DFS); C:progression-free survival (PFS); D:recurrence 图 4 发表偏倚漏斗图 Figure 4 Funnel plot of publication bias |

CTCs是指由肿瘤原发灶或转移灶释放进入外周血中的具有肿瘤基因或特异性抗原参数的肿瘤细胞, 其中大部分被机体自身的免疫系统识别并清除, 只有少数肿瘤细胞会获得新的特征而存活, 并随着血液循环到达远处器官或组织中种植形成微转移灶, 最终发展成为远处转移[3]。CTCs检测作为一种新兴的“液体活检”技术, 具有取样简单、实时、无创、便捷等优点, 为实时监测肿瘤在治疗过程中的变化情况提供了新的更简便的工具[31]。CTCs作为目前肿瘤研究领域的热点之一, 引起了国内外众多研究者的强烈兴趣。随着研究的不断深入, 越来越多的证据已经证明了CTCs在乳腺癌、肺癌、前列腺癌等不同类型实体瘤中具有辅助诊断、转移复发预警及预后评估等积极的临床意义[3]。近年来, CTCs检测在头颈恶性肿瘤诊断及预后中的作用亦有报道, 其临床意义也越来越受到重视[32]。

在本研究中, 我们首先对头颈恶性肿瘤患者外周血中CTCs检测的预后评估价值进行了综合分析, 结果表明外周血CTCs阳性的患者具有更短的OS、DFS和PFS, 以及更高的复发转移风险, 此结果强烈提示了CTCs阳性的头颈恶性肿瘤患者在经过治疗后更容易发生肿瘤复发或转移, 且预后也较差。此外, 本研究结果也表明, CTCs的检测与肿瘤的T分期、N分期和TNM分期显著相关, 而与患者的年龄、性别和肿瘤组织学分级无关, 这提示外周血中CTCs阳性更倾向于肿瘤浸润深度更深(T3~T4)、淋巴结转移更多(N3)以及分期更晚(Ⅲ~Ⅳ)的患者。研究表明, 头颈肿瘤的复发转移主要包括头颈部淋巴结复发、肺转移、骨转移以及肝转移等[2]。CTCs作为恶性肿瘤远处转移的“介导者”, 可通过血液循环到达肺、肝、骨等远隔器官, 形成转移灶; 同时, 也有研究证实其可通过淋巴管道, 到达淋巴结, 导致淋巴结的局部复发[33]。因此, 外周血中CTCs检测阳性的头颈部恶性肿瘤患者, 具有更高的局部复发和远处转移风险, 需要在标准化治疗的基础上制定更加合理的个性化治疗和随访措施, 以延缓疾病进展和复发的时间, 延长患者的生存期。然而, 关于到底是哪一些头颈部恶性肿瘤类型的肿瘤细胞更容易在循环出现以及CTCs检测阳性与肿瘤复发转移部位的关系, 目前尚无研究去确切证实, 我们的纳入研究中也未进行相应的报道。既往研究表明, 上皮间质转化(epithelial to mesenchymal transition, EMT)在CTCs的形成过程中扮演了非常关键的角色, 原发灶的上皮性肿瘤细胞通过EMT获得间质特性, 增强侵袭能力, 从而更易突破血管壁, 进入血液形成CTCs[34], 这也间接证实了外周血中CTCs的形成与数目多少与肿瘤的侵袭能力密切相关, 因此, 我们推测分化程度更低的头颈部恶性肿瘤可能更容易在外周血中检测出CTCs。而根据CTCs需要通过机体的脉管进行移动的特点和头颈部肿瘤的病理特征以及头颈部的解剖结构特点, 我们推测CTCs介导的肿瘤复发可能更多地是通过淋巴管道引起的局部淋巴结复发, CTCs引起的远处器官转移可能以肺转移和骨转移更为多见, 当然, 具体结论需要更多的临床研究加以证实。尽管如此, 我们的探究结果证实了头颈恶性肿瘤患者外周血CTCs检测不仅可用于预测预后, 还可用于协助医生评估患者的复发转移风险, 找到高风险的患者并尽早进行积极的治疗, 从而达到改善治疗效果、延长患者生存期的目的。而且, 基于CTCs检测的多种优势, 其在协助头颈恶性肿瘤的精准术前评估和制定标准化治疗方案等方面也具有巨大的临床应用潜力。

尽管敏感度分析结果提示研究结果稳定可靠, 但本研究仍存在一定的局限性:缺乏灰色文献、可能会漏掉阴性结果的研究; 此外, CTCs检测方法不同, 对结果影响很大。同时, CTCs与人体肿瘤负荷关系密切, 手术前后CTCs检测的阳性率也明显不同。在我们的研究中, 纳入文献中涉及多种CTCs检测方法, 采样时间也存在差异, 这可能是研究间异质性的主要来源。然而, 由于各组间纳入研究的数量有限, 无法根据检测方法和采样时间进行亚组分析和Meta回归分析, 以明确不同检测方法和采样时间对研究结果的影响。此外, 由于大部分纳入研究的样本采集均在治疗开始前, 即基线水平, 加上大部分纳入研究未报道是否行手术以及手术前后外周血中CTCs检测的预后差异, 因此, 我们也无法根据术前和术后进行亚组分析, 以明确两个不同时间点CTCs检测的预后价值。关于检测方法、采样时间以及手术对头颈部恶性肿瘤CTCs预后价值的影响, 需要进行更多、更大规模且设计严谨的高质量临床研究去证实。

综上所述, 在头颈恶性肿瘤患者中, 外周血CTCs在具有重要的预后评估价值, CTCs阳性提示预后不良, 且与肿瘤的浸润深度、淋巴结转移和分期显著相关, 有望应用于临床成为疗效监测和预后评估的重要标志物。

| [1] | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65(2): 87–108. DOI:10.3322/caac.21262 |

| [2] | Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:update on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2016, 91(3): 386–96. DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.12.017 |

| [3] | Lianidou ES, Strati A, Markou A. Circulating tumor cells as promising novel biomarkers in solid cancers[J]. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci, 2014, 51(3): 160–71. DOI:10.3109/10408363.2014.896316 |

| [4] | 潘淋淋, 段俊武, 乔伟强, 等. 循环肿瘤细胞与可手术乳腺癌预后相关性的meta分析[J]. 中国老年学杂志, 2017, 37(20): 5079–82. [ Pan LL, Duan JW, Qiao WQ, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in patients with operable breast cancer:a meta-analysis[J]. Zhongguo Lao Nian Xue Za Zhi, 2017, 37(20): 5079–82. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2017.20.056 ] |

| [5] | Xu T, Shen G, Cheng M, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells in patients with lung cancer:a meta-analysis[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(37): 62524–36. |

| [6] | 石晓欣, 安建虹, 黄业恩, 等. 循环肿瘤细胞和播散肿瘤细胞对食管癌患者预后的meta分析[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2017, 37(2): 266–73. [ Shi XX, An JH, Huang YE, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells and disseminated tumor cells in patients with esophageal cancer:a meta-analysis[J]. Nanfang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao, 2017, 37(2): 266–73. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4254.2017.02.21 ] |

| [7] | Tan Y, Wu H. The significant prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in colorectal cancer:A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Curr Probl Cancer, 2018, 42(1): 95–106. DOI:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2017.11.002 |

| [8] | 曹宇勃, 许崇安. 循环肿瘤细胞对胰腺癌患者预后评估价值的meta分析[J]. 中国全科医学, 2014, 12(20): 2357–61. [ Cao YB, Xu CA. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in patients with pancreatic cancer:A meta-analysis[J]. Zhongguo Quan Ke Yi Xue, 2014, 12(20): 2357–61. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2014.20.017 ] |

| [9] | Zhou Y, Bian B, Yuan X, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer:A meta-analysis[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(6): e0130873. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0130873 |

| [10] | 谭祎, 刘艳, 宋羽葳, 等. 循环肿瘤细胞与转移性前列腺癌患者预后关系的Meta分析[J]. 肿瘤防治研究, 2016, 43(9): 783–8. [ Tan Y, Liu Y, Song YW, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells for metastatic prostate cancer:A meta-analysis[J]. Zhong Liu Fang Zhi Yan Jiu, 2016, 43(9): 783–8. DOI:10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2016.09.011 ] |

| [11] | Hsieh JC, Lin HC, Huang CY, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells with podoplanin expression in patients with locally advanced or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Head Neck, 2015, 37(10): 1448–55. DOI:10.1002/hed.v37.10 |

| [12] | Inhestern J, Oertel K, Stemmann V, et al. Prognostic role of circulating tumor cells during induction chemotherapy followed by curative surgery combined with postoperative radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7): e132901. |

| [13] | Grisanti S, Almici C, Consoli F, et al. Circulating tumor cells in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck carcinoma:prognostic and predictive significance[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(8): e103918. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0103918 |

| [14] | Weller P, Nel I, Hassenkamp P, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cell subpopulations in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(12): e113706. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0113706 |

| [15] | Tinhofer I, Konschak R, Stromberger C, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells for prediction of recurrence after adjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck[J]. Ann Oncol, 2014, 25(10): 2042–7. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdu271 |

| [16] | Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis[J]. Trials, 2007, 8: 16. DOI:10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 |

| [17] | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2010, 25(9): 603–5. DOI:10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z |

| [18] | Zhang H, Gong S, Liu Y, et al. Enumeration and molecular characterization of circulating tumor cell using an in vivo capture system in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2017, 29(3): 196–203. DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.03.05 |

| [19] | Li F, Liu J, Song D, et al. Circulating tumor cells in the blood of poorly differentiated nasal squamous cell carcinoma patients:correlation with treatment response[J]. Acta Otolaryngol, 2016, 136(11): 1164–7. DOI:10.1080/00016489.2016.1201861 |

| [20] | Gröbe A, Blessmann M, Hanken H, et al. Prognostic relevance of circulating tumor cells in blood and disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2014, 20(2): 425–33. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1101 |

| [21] | Bozec A, Ilie M, Dassonville O, et al. Significance of circulating tumor cell detection using the CellSearch system in patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 2013, 270(10): 2745–9. DOI:10.1007/s00405-013-2399-y |

| [22] | He S, Li P, He S, et al. Detection of circulating tumour cells with the CellSearch system in patients with advanced-stage head and neck cancer:preliminary results[J]. J Laryngol Otol, 2013, 127(8): 788–93. DOI:10.1017/S0022215113001412 |

| [23] | Buglione M, Grisanti S, Almici C, et al. Circulating tumour cells in locally advanced head and neck cancer:preliminary report about their possible role in predicting response to non-surgical treatment and survival[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2012, 48(16): 3019–26. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.007 |

| [24] | Nichols AC, Lowes LE, Szeto CC, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in advanced head and neck cancer using the CellSearch system[J]. Head Neck, 2012, 34(10): 1440–4. DOI:10.1002/hed.21941 |

| [25] | Hristozova T, Konschak R, Stromberger C, et al. The presence of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) correlates with lymph node metastasis in nonresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck region (SCCHN)[J]. Ann Oncol, 2011, 22(8): 1878–85. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdr130 |

| [26] | Jatana KR, Balasubramanian P, Lang JC, et al. Significance of circulating tumor cells in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck:initial results[J]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2010, 136(12): 1274–9. DOI:10.1001/archoto.2010.223 |

| [27] | Toyoshima T, Vairaktaris E, Nkenke E, et al. Hematogenous cytokeratin 20 mRNA detection has prognostic impact in oral squamous cell carcinoma:preliminary results[J]. Anticancer Res, 2009, 29(1): 291–7. |

| [28] | Guney K, Yoldas B, Ozbilim G, et al. Detection of micrometastatic tumor cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.A possible predictor of recurrences?[J]. Saudi Med J, 2007, 28(2): 216–20. |

| [29] | Wirtschafter A, Benninger MS, Moss TJ, et al. Micrometastatic tumor detection in patients with head and neck cancer:a preliminary report[J]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2002, 128(1): 40–3. DOI:10.1001/archotol.128.1.40 |

| [30] | 张海东, 龚单春, 刘亚群, 等. 循环肿瘤细胞在头颈部鳞状细胞癌中意义的初步研究[J]. 中华耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志, 2017, 53(1): 39–44. [ Zhang H, Gong D, Liu Y, et al. The significance of circulating tumor cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma:a preliminary study[J]. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2017, 53(1): 39–44. ] |

| [31] | Sharma S, Zhuang R, Long M, et al. Circulating tumor cell isolation, culture, and downstream molecular analysis[J]. Biotechnol Adv, 2018, 36(4): 1063–78. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.03.007 |

| [32] | Mcmullen KP, Chalmers JJ, Lang JC, et al. Circulating tumor cells in head and neck cancer:A review[J]. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2016, 2(2): 109–16. DOI:10.1016/j.wjorl.2016.05.003 |

| [33] | Mesker WE, Vrolijk H, Sloos WC, et al. Detection of tumor cells in bone marrow, peripheral blood and lymph nodes by automated imaging devices[J]. Cell Oncol, 2006, 28(4): 141–50. |

| [34] | Jie XX, Zhang XY, Xu CJ. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, circulating tumor cells and cancer metastasis:Mechanisms and clinical applications[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(46): 81558–71. |

2018, Vol. 45

2018, Vol. 45