文章信息

- 直肠癌治疗新模式——全程新辅助治疗

- New Pattern of Rectal Cancer Treatment: Total Neoadjuvant Therapy

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2018, 45(9): 701-706

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2018, 45(9): 701-706

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2018.18.0103

- 收稿日期: 2018-01-23

- 修回日期: 2018-03-20

结直肠癌的发病例数正在逐步升高,2014年“世界癌症报告”显示,全球结直肠癌发病率仅次于肺癌和乳腺癌,居第3位,死亡率居第4位[1]。随着我国城市化的发展,结直肠癌发病死亡率逐年升高[2],而美国结直肠癌发病率及病死率均呈下降趋势,且生存呈改善趋势[3-4],说明中国结直肠癌综合诊治水平与美国仍有一定差距。直肠癌发病率约占结直肠癌的2/5,特别对于20~49岁年龄段人群,其逐年升高的病死率和诊断延迟密切相关,多数患者确诊时已为局部进展期。根治性手术联合围手术期辅助放化疗的应用使局部复发率从25%~40%降至10%以下[5-9],但是远处复发率仍高达25%~30%[10-13]。传统“三明治”治疗模式在降低局部复发率的同时却使远处转移风险凸显,影响患者长期生存。近期,有较多临床研究将辅助化疗提至术前,称为全程新辅助治疗(total neoadjuvant therapy, TNT)[14],该治疗模式已被NCCN收录指导临床,但国内有关该治疗模式的报道较少,本文就该模式治疗直肠癌的相关研究作一综述,旨在提高对直肠癌围手术期辅助治疗的认识。

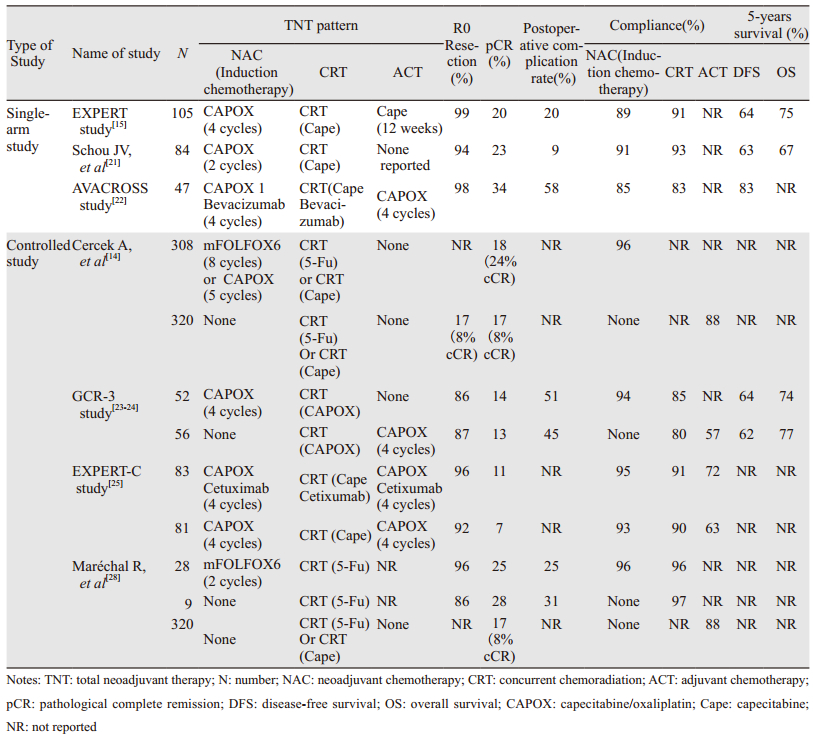

1 TNT的相关临床研究(见表 1)EXPERT研究[15]纳入77例局部进展期直肠癌(locally advanced rectal cancer, LARC)患者,术前4周期卡培他滨+奥沙利铂(capecitabine+oxaliplatin, CapeOX)方案后行放化疗,诱导化疗期间8例患者发生心脏及血栓栓塞事件,其中3例分别因肺栓塞、心肌梗死、心力衰竭死亡,Chau等[15]合并此研究与另一项Ⅱ期试验显示,6.5%(10/153)的患者出现心脏不良反应,并且多发生在第一个周期诱导化疗期间。但既往研究却显示同样的CapeOX方案并未增加心脏血栓栓塞风险[16]。机体二氢嘧啶脱氢酶(DPD)的缺乏会增加卡培他滨相关心脏毒性[17-19]。随后Chua等[20]更新EXPERT研究为105例LARC患者,只有1例新发致命肺动脉栓塞。该研究放化疗后客观有效率由诱导化疗后的74%提高至89%,76%的患者获得不同程度T、N降期,26例患者出现复发,远处复发率22%(21/95),局部复发率6%(6/95),5年无进展生存率(PFS)64%,总生存率(OS)75%。同样,Schou等[21]研究中,84例LARC患者,RO切除率94%(72/77),其中23%(19/84)达到病理完全缓解(pathological complete remission, pCR)。69%(53/77)获得T降期。诱导化疗及放化疗期间3~4级不良反应发生率分别为18%和11%。以上研究表明诱导化疗序贯放化疗较传统单一模式具有更好的降期作用,该模式虽然延长了术前治疗时间,但并未增加疾病进展风险和远期复发率,但是对于既往心肌缺血血栓栓塞病史患者采用CapeOX诱导方案可能会增加心血管不良反应的发生风险,因此及时识别不良反应、终止治疗,选择合适替代方案在风险患者的个体化疗中显得至关重要。

AVACROSS[22]研究进一步探索贝伐珠单抗在TNT模式中的安全性及可行性,47例患者中45例行手术治疗,36%(16/45)患者获得pCR,38%(17/45)患者Ⅲ度肿瘤消退。39例完成全程治疗的患者中,83%获得Ⅲ~Ⅳ度肿瘤消退。入组患者中47%的患者为T3N1期,与其他研究相比,相对早期患者数目比例较多,因此该研究较高的pCR可能与该分期患者比例较多相关,该研究样本并不能有力代表LARC患者。此外,该研究术后较高的并发症及二次手术率使贝伐珠单抗在TNT中运用的安全性受到质疑,仍需更多临床试验验证。

1.2 对照试验GCR-3研究[23-24]比较了TNT与传统模式的短期疗效与长期效果。对照组辅助化疗与TNT组诱导化疗3~4级不良反应发生率分别为54%(20/37)和19%(10/54)(P=0.004),放化疗期间不良反应发生率(P=0.36)及术后30天不良反应发生率(P=0.3)均无统计学差异,两组5年局部复发率为2%和5%(P=0.61),远处复发率为21%和23%(P=0.79),5年DFS(P=0.85)及5年OS(P=0.64)比较差异均无统计学意义。转移灶对放化疗的敏感度低于原发肿瘤,沿用传统放化疗方案疗程及剂量可能并未达到抑制或根治潜在转移灶的有效强度阈值,而且相比传统模式组有51%的患者完成4周期化疗,高达25%患者未进行任何术后辅助治疗,TNT组100%患者进行了诱导化疗,并且92%的患者完成了4个周期,表明TNT模式具有低化疗毒性及高依从性。EXPERT-C研究[25]发现西妥昔单抗的应用增加了KAS/BRAF基因野生型患者的缓解率(71% vs. 51%, P=0.038),并且有明显总生存获益(HR=0.27, 95%CI: 0.07~0.99, P=0.034)。多因素分析显示根据磁共振评估肿瘤消退分级(MRI-assessed tumor regression grading, mrTRG)能预测PFS和OS,并且mrTRG3患者更能从随后的同步放化疗中获益[26-27],这对评估患者新辅助化疗(neoadjavant chemotherapy, NAC)后是否需要进行放化疗具有重要意义。Maréchal等[28]探究mFOLFOX6方案在TNT中的应用,术后ypT0-1N0率分别为34%和32%(P=0.85),此外,两组肿瘤消退分级、肿瘤降期率、括约肌保留率比较差异均无统计学意义。两组中仅对照组出现一例肿瘤进展,为TNT带来了循证医学依据。

2017年ASCO会议上,Cercek等[14]报道一项研究,共入组628例LARC患者,其中320例接受传统同步放化疗+全直肠系膜切除术+辅助化疗(CRT+TME+ACT)方案治疗,308例给予TNT治疗,化疗方案为FOLFOX或CAPOX,结果TNT组较传统治疗组完成度高(P < 0.001),在pCR、cCR及降期患者中远处复发率降低,并且完全缓解发生率(complete response)包括pCR和临床完全缓解(clinical complete response, cCR)高于传统治疗组。

2 TNT的潜在优缺点 2.1 TNT的潜在优点理论上,TNT具有以下优势:(1)可在较早阶段干预微转移;(2)降低肿瘤负荷及分期;(3)可避免放疗及手术对原始肿瘤结构的破坏,利用肿瘤原始血供,提高药物灌注率;(4)提高R0切除率及器官保留率;(5)与术后放化疗相比,TNT可早期控制症状,具有较高的患者依从性和耐受性,确保剂量强度;(6)评估机体及肿瘤对化疗药物的反应,作为体内药敏资料指导治疗;(7)抑制手术引起的肿瘤增殖刺激;(8)避免术后患者延迟化疗风险,明显缩短无术后化疗患者造瘘期;(9)降低肿瘤细胞活性,一定程度上减少游离肿瘤细胞,减少放疗及手术引起的转移及种植风险;(10)不显著增加成本,化疗周期的缩短还可在一定程度上降低成本。对于达到临床病理完全缓解的患者,可以等待观察,规避手术。因此,TNT已成为极具潜力的研究方向。

2.2 TNT的潜在缺点理论上,TNT存在以下缺点:(1)术前治疗期延长,增加无反应患者短期潜在的进展风险;(2)影响机体免疫状态,降低患者手术耐受性;(3)增加围手术期不良反应的发生风险。

3 TNT模式的争议和困惑 3.1 评估治疗反应策略在术前辅助治疗模式中,评估肿瘤对放化疗的有效性非常重要,其准确性直接影响阶段治疗策略。有研究尝试寻找短期指标作为长期结局的预测因子,病理肿瘤消退分级(pathological tumor regression grading, pTRG)中Dworak等[29]制定的标准应用较广泛,其根据肿瘤细胞残余及纤维化程度对接受新辅助放化疗患者的术后病理进行分析,TRG4的患者10年累积远处转移发生率和DFS分别为10.5%和89.5%,而TRG2-3(肿瘤中度消退)的患者分别为29.3%和73.6%,TRG0/1(肿瘤很少消退)的患者分别为39.6%和63%(P=0.005, P=0.008)[30]。但是pTRG的评估依赖术后病理标本,无法应用于术前,盆腔磁共振及其功能成像建立的磁共振肿瘤消退分级(mrTRG)已被广泛应用于直肠癌临床诊断及治疗反应监测中[20, 31-33],MERCURY研究证明mrTRG能够评估治疗反应,并且预测远期生存,肿瘤消退在磁共振上表现为纤维间质信号填充,mrTRG1-3定义为肿瘤纤维化程度低,肿瘤消退较少,mrTRG4-5定义为纤维化程度高,退缩明显,mrTRG4-5组与mrTRG1-3组生存差异有统计学意义,DFS分别为31%和64%(P=0.007),5年OS分别为27%和72%(P=0.001)[26],但传统T2加权像对于区分残余病灶及纤维化敏感度较差,其联合功能成像如DWI序列可提高灵敏度[34]。mrTRG的临床意义在于指导术前放化疗决策,根据肿瘤消退情况更换治疗模式或者增大治疗强度或即刻行手术治疗或者观察等待。但也有Meta分析显示mrTRG分级并未体现出患者生存差异,并且mrTRG和pTRG一致性较差,不能作为替代指标[35]。

3.2 TNT模式放化疗方案选择术前同步放化疗模式中,卡培他滨的疗效已得到证实,一项随机对照研究对比了卡培他滨和5-Fu的疗效,结果显示术后远处转移分别为19%和28%(P=0.04),并且卡培他滨具有生存优势[36],另一项研究显示卡培他滨组同步放化疗较5-Fu组提高了R0切除率(93% vs. 97%, P=0.024)[37]。卡培他滨特殊的作用机制、用药方式、安全及确切的疗效,使其可替代5-Fu作为诱导化疗的首选用药。对于局部进展期直肠癌,有研究表明术前放化疗加入奥沙利铂并未带来额外的肿瘤退缩及生存获益[24, 38-39],Ⅱ期试验GCR-3中即使术前放化疗剂量强度未调整,诱导化疗的加入并未增加随后放化疗3~4级不良反应发生率。同样,与术后辅助化疗相比,奥沙利铂联合卡培他滨并未增加3~4级不良反应发生率[23-24]。

3.3 临床完全缓解(cCR)的判断与处理局部进展期中低位直肠癌接受术前辅助治疗的患者,有15%~20%经过严密检查和随访达到cCR[40],推荐采用直肠指诊、消化内镜、MRI-DWI-T2成像、血清CEA等判断有无可疑淋巴结转移和远处转移等综合指标来判断[41],不推荐消化超声内镜或磁共振单一检查[42-43]。对于获得cCR的患者是否给予手术治疗目前尚存在争议,有研究提出等待观察策略,避免手术治疗给患者带来的相关并发症和围手术期死亡风险。Renehan等[44]通过比较等待观察策略获得cCR的21位患者与术后病理完全缓解(pCR)的20位患者的生存状况,两组患者2年DFS分别为89%和93%(P=0.770),OS分别为100%和91%(P=0.228),差异无统计学意义,同样该研究通过倾向评分匹配法,以T分期、年龄和行为状态评分为匹配指标,对照分析等待观察策略组和根治性手术组218名患者生存差异,结果显示两组3年DFS为88%和78%(time-varying, P=0.043),3年OS分别为96%和87%(time-varying, P=0.024),差异也没有统计学意义,表明等待观察策略的生存并不劣于根治性手术方案。值得注意的是129例cCR患者,中位随访时间33月,单纯局部复发41例,同时合并远处转移3例,单纯远处转移4例,36例单纯局部复发患者接受了手术治疗,5例接受了姑息治疗,由此可见60%的cCR患者规避了根治性手术,36例补救手术患者预后指标未见报道。有研究对等待观察策略患者生活质量进行评估,结果表明等待观察策略组较根治性手术组具有更好的生理及认知机能,在排便、排尿及性功能方面尤其突出[45]。可见,经过严格的检查、随访监测及采取及时补救措施,等待观察策略是安全的。

3.4 多学科诊治在TNT中的实施TNT模式与传统“三明治”模式相比,延长了术前新辅助治疗的时间,使治疗模式的选择、治疗反应评估以及阶段性决策变得更加困难,单一专科更加无法胜任直肠癌患者的个体和规范化治疗。以外科为核心的消化道多学科团队(MDT)的建立可以在一定程度上改善这种状态。越来越多的临床研究表明多学科协作模式能做到准确诊断、科学施治、规范随访、避免过度诊疗和误诊误治,改善患者生存[46-48]。但有研究表明MDT会增加患者异时性远处转移率[49], MDT的建立是否会增加直肠癌患者从确诊到初始治疗的间隔时间尚存在争议[50-51],可以将患者确诊至初始治疗间隔时间作为评估MDT团队效率的指标。

4 小结TNT模式作为直肠癌综合治疗新模式虽然已经被NCCN指南用于指导临床,但其安全性、有效性以及临床经济学仍需大量临床研究评估。类似于传统治疗模式,TNT模式是挑战和机遇的结合体,需要更多的学科参与、更多的资金及精力投入,更是检验临床肿瘤中心MDT团队合作能力的利器。

| [1] | International Agency for Research on Cancer. World cancer report 2014[M]. Stewart BW, Wild CP ed: Lyon, 2014. |

| [2] | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. Ca Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(2): 115–32. DOI:10.3322/caac.21338 |

| [3] | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(3): 177–93. DOI:10.3322/caac.v67.3 |

| [4] | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(1): 7–30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21387 |

| [5] | Havenga K, Enker WE, Norstein J, et al. Improved survival and local control after total mesorectal excision or D3 lymphadenectomy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer: an international analysis of 1411 patients[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 1999, 25(4): 368–74. DOI:10.1053/ejso.1999.0659 |

| [6] | Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Westerheim O, et al. Local recurrence after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2002, 28(2): 126–34. DOI:10.1053/ejso.2001.1231 |

| [7] | Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, et al. Chemotherapy with Preoperative Radiotherapy in Rectal Cancer[J]. New Engl J Med, 2006, 355(11): 1114–23. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa060829 |

| [8] | Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373(9666): 811–20. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60484-0 |

| [9] | Methy N, Bedenne L, Conroy T, et al. Surrogate end points for overall survival and local control in neoadjuvant rectal cancer trials: statistical evaluation based on the FFCD 9203 trial[J]. Ann Oncol, 2010, 21(3): 518–24. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdp340 |

| [10] | Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2004, 351(17): 1731–40. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa040694 |

| [11] | Gérard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(28): 4620–5. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7629 |

| [12] | Collette L, Bosset JF, Den DM, et al. Patients with curative resection of cT3-4 rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy: does anybody benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy? A trial of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiation Oncology Group[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2007, 25(28): 4379–86. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9685 |

| [13] | Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, et al. Fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: long-term results of the EORTC 22921 randomised study[J]. Lancet Oncology, 2014, 15(2): 184–90. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70599-0 |

| [14] | Cercek A, Roxburgh CS, Strombom P, et al. Adoption of Total Neoadjuvant Therapy for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2018, 4(6): e180071. DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0071 |

| [15] | Chau I, Brown G, Cunningham D, et al. Neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by synchronous chemoradiation and total mesorectal excision in magnetic resonance imaging-defined poor-risk rectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(4): 668–74. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4875 |

| [16] | Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Twelves C, et al. XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin): active first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2004, 22(11): 2084–91. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2004.11.069 |

| [17] | Frickhofen N, Beck FJ, Jung B, et al. Capecitabine can induce acute coronary syndrome similar to 5-fluorouracil[J]. Ann Oncol, 2002, 13(5): 797–801. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdf035 |

| [18] | Saif MW, Garcon MC, Rodriguez G, et al. Bolus 5-fluorouracil as an alternative in patients with cardiotoxicity associated with infusion 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine: a case series[J]. In Vivo, 2013, 27(4): 531–4. |

| [19] | Saif MW, Smith M, Maloney A. The First Case of Severe Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Associated with 5-Fluorouracil in a Patient with Abnormalities of Both Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase (DPYD) and Thymidylate Synthase (TYMS) Genes[J]. Cureus, 2016, 8(9): e783. |

| [20] | Chua YJ, Barbachano Y, Cunningham D, et al. Neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin before chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision in MRI-defined poor-risk rectal cancer: a phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2010, 11(3): 241–8. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70381-X |

| [21] | Schou JV, Larsen FO, Rasch L, et al. Induction chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiotherapy before total mesorectal excision in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(10): 2627–33. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mds056 |

| [22] | Nogué M, Salud A, Vicente P, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to XELOX induction therapy plus concomitant capecitabine-based chemoradiotherapy in magnetic resonance imaging-defined poor-prognosis locally advanced rectal cancer: the AVACROSS study[J]. Oncologist, 2011, 16(5): 614–20. DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0285 |

| [23] | Fernández-Martos C, Pericay C, Aparicio J, et al. Phase Ⅱ, randomized study of concomitant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) compared with induction CAPOX followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in magnetic resonance imaging-defined, locally advanced rectal cancer: Grupo cancer de recto 3 study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2010, 28(5): 859–65. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.8541 |

| [24] | Fernández-Martos C, Garcia-Albeniz X, Pericay C, et al. Chemoradiation, surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy versus induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation and surgery: long-term, results of the Spanish GCR-3 phase Ⅱ randomized trial[J]. Ann Oncol, 2015, 26(8): 1722–8. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdv223 |

| [25] | Dewdney A, Cunningham D, Tabernero J, et al. Multicenter Randomized Phase Ⅱ Clinical Trial Comparing Neoadjuvant Oxaliplatin, Capecitabine, and Preoperative Radiotherapy With or Without Cetuximab Followed by Total Mesorectal Excision in Patients With High-Risk Rectal Cancer (EXPERT-C)[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2012, 30(14): 1620–7. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6036 |

| [26] | Patel UB, Taylor F, Blomqvist L, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Detected Tumor Response for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Predicts Survival Outcomes: MERCURY Experience[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(28): 3753–60. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9068 |

| [27] | Sclafani F, Brown G, Cunningham D, et al. PAN-EX: a pooled analysis of two trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy in MRI-defined, locally advanced rectal cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2016, 27(8): 1557–65. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdw215 |

| [28] | Maréchal R, Vos B, Polus M, et al. Short course chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomized multicentric phase Ⅱ study[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(6): 1525–30. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdr473 |

| [29] | Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 1998, 13(1): 54–5. DOI:10.1007/s003840050134 |

| [30] | Fokas E, Liersch T, Fietkau R, et al. Tumor regression grading after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma revisited: updated results of the CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2014, 32(15): 1554–62. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.3769 |

| [31] | Pham TT, Liney G, Wong K, et al. Study protocol: multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging for therapeutic response prediction in rectal cancer[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 465. DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3449-4 |

| [32] | Neri E, Guidi E, Pancrazi F, et al. MRI tumor volume reduction rate vs tumor regression grade in the pre-operative re-staging of locally advanced rectal cancer after chemo-radiotherapy[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2015, 84(12): 2438–43. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.08.008 |

| [33] | Siddiqui MR, Bhoday J, Battersby NJ, et al. Defining response to radiotherapy in rectal cancer using magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological scales[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(37): 8414–34. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8414 |

| [34] | van der Paardt Mp, Zagers MB, Beets-Tan RG, et al. Patients who undergo preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer restaged by using diagnostic MR imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Radiology, 2013, 269(1): 101–12. DOI:10.1148/radiol.13122833 |

| [35] | Sclafani F, Brown G, Cunningham D, et al. Comparison between MRI and pathology in the assessment of tumour regression grade in rectal cancer[J]. Br J Cancer, 2017, 117(10): 1478–85. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2017.320 |

| [36] | Hofheinz RD, Wenz F, Post S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine versus fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2012, 13(6): 579–88. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70116-X |

| [37] | Ramani VS, Sun MA, Montazeri A, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: a comparison between intravenous 5-fluorouracil and oral capecitabine[J]. Colorectal Dis, 2010, 12(Suppl 2): 37–46. |

| [38] | Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, et al. Neoadjuvant 5-FU or Capecitabine Plus Radiation With or Without Oxaliplatin in Rectal Cancer Patients: A Phase Ⅲ Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2015, 107(11). |

| [39] | Aschele C, Cionini L, Lonardi S, et al. Primary Tumor Response to Preoperative Chemoradiation With or Without Oxaliplatin in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Pathologic Results of the STAR-01 Randomized Phase Ⅲ Trial[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(20): 2773–80. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4911 |

| [40] | Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data.[J]. Lancet Oncology, 2010, 11(9): 835–44. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8 |

| [41] | Habrgama A, Perez RO, Wynn G, et al. Complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer: characterization of clinical and endoscopic findings for standardization[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2010, 53(12): 1692–8. DOI:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f42b89 |

| [42] | Pastor C, Subtil JC, Sola J, et al. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound to assess tumor response after neoadjuvant treatment in rectal cancer: can we trust the findings?[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2011, 54(9): 1141–6. DOI:10.1097/DCR.0b013e31821c4a60 |

| [43] | Sassen S, de Booij M, Sosef M, et al. Locally advanced rectal cancer: is diffusion weighted MRI helpful for the identification of complete responders (ypT0N0) after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy?[J]. Eur Radiol, 2013, 23(12): 3440–9. DOI:10.1007/s00330-013-2956-1 |

| [44] | Renehan AG, Malcomson L, Emsley R, et al. Watch-and-wait approach versus surgical resection after chemoradiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer (the OnCoRe project): a propensity-score matched cohort analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 17(2): 174–83. |

| [45] | Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients After Chemoradiation: Watch-and-Wait Policy Versus Standard Resection-A Matched-Controlled Study[J]. Dis Colon Rectum, 2017, 60(10): 1032–40. DOI:10.1097/DCR.0000000000000862 |

| [46] | Brännström F, Bjerregaard JK, Winbladh A, et al. Multidisciplinary team conferences promote treatment according to guidelines in rectal cancer[J]. Acta Oncol, 2015, 54(4): 447–53. DOI:10.3109/0284186X.2014.952387 |

| [47] | Richardson B, Preskitt J, Lichliter W, et al. The effect of multidisciplinary teams for rectal cancer on delivery of care and patient outcome: has the use of multidisciplinary teams for rectal cancer affected the utilization of available resources, proportion of patients meeting the standard of care, and does this translate into changes in patient outcome?[J]. Am J Surg, 2016, 211(1): 46–52. DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.015 |

| [48] | Lan YT, Jiang JK, Chang SC, et al. Improved outcomes of colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases in the era of the multidisciplinary teams[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2016, 31(2): 403–11. DOI:10.1007/s00384-015-2459-4 |

| [49] | Wille-Jørgensen P, Sparre P, Glenthøj A, et al. Result of the implementation of multidisciplinary teams in rectal cancer[J]. Colorectal Dis, 2013, 15(4): 410–3. DOI:10.1111/codi.2013.15.issue-4 |

| [50] | Kozak VN, Khorana AA, Amarnath S, et al. Multidisciplinary Clinics for Colorectal Cancer Care Reduces Treatment Time[J]. Clin Colorectal Cancer, 2017, 16(4): 366–71. DOI:10.1016/j.clcc.2017.03.020 |

| [51] | Nikolovski Z, Watters DAK, Stupart D, et al. Colorectal multidisciplinary meetings: how do they affect the timeliness of treatment?[J]. Anz J Surg, 2017, 87(10): E112–5. DOI:10.1111/ans.13144 |

2018, Vol. 45

2018, Vol. 45