文章信息

- MB-WCX联合MALDI-TOF MS建立结直肠癌血清诊断模型

- Established of Serum Diagnostic Model for Colorectal Cancer Patients Using MB-WCX and MALDI-TOF MS

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2018, 45(6): 386-390

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2018, 45(6): 386-390

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2018.17.1276

- 收稿日期: 2017-10-11

- 修回日期: 2017-12-06

2. 710003 西安,西安市中心医院普外科;

3. 710068 西安,陕西省人民医院普外科;

4. 710068 西安,陕西省人民医院病理科

2. Department of General Surgery, Xi'an Central Hospital, Xi'an 710003, China;

3. Department of General Surgery, Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital, Xi'an 710068, China;

4. Department of Pathology, Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital, Xi'an 710068, China

结直肠癌的发病率居所有肿瘤的第三位,死亡率位居第四位[1]。近40年来,该疾病的死亡率从28.6/10万人下降了约51%,其中,筛查和早期诊断的进步贡献最大,约占53%,而治疗方法的改进仅占约12%[2]。目前结直肠癌的筛查手段主要包括粪便潜血、肠镜、CT/MRI,血清CEA检测等,但不幸的是早期诊断者仅占约40%[3]。蛋白质谱能够快速、高通量检测不同病理类型下不同标本的蛋白表达差异,为筛选肿瘤诊断和预后标志物提供了新思路[4-6]。目前已有利用质谱技术建立结直肠癌诊断模型及筛选标志物的探索,但其敏感度及特异性存在较大差异,尚未在临床中应用[7-13]。本研究我们运用磁珠分离联合质谱分析结直肠正常组织、结直肠癌术前及术后患者血清蛋白表达是否存在差异,现报道如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 资料与仪器 1.1.1 临床资料本研究经过陕西省人民医院伦理委员会批准通过。收集2014年9月1日—2016年9月1日我院结直肠正常组织、结直肠癌组织术前及术后血清标本各72例,结直肠正常组织作为正常对照组,其中男36例、女36例,平均年龄(63.77±11.83)岁;结直肠癌组男39例、女33例,平均年龄(65.83±9.14)岁。诊断模型验证血清标本来自陕西省人民医院胃肠道肿瘤生物样本库,其中正常对照组男30例、女30例,平均年龄(60.21±13.55)岁;结直肠癌组男33例、女27例,平均年龄(65.42±15.38)岁。标本的收集均征得患者的知情同意并签署书面同意书,全部患者有完整的治疗和随访资料。所有病例均未行放化疗和(或)靶向治疗。

1.1.2 样本采集被研究者采集清晨空腹外周血3 ml于无抗凝剂真空干燥管,4℃静置1 h,4℃,3000 g离心1 h,收集血清分装于500 μl EP管,存放于-80℃备用。

1.1.3 试剂和仪器MB-WCX试剂盒购自德国Bruker Daltonics公司;质谱系统:MALDI-TOF MS,德国Bruker Daltonics公司;超高效液相系统:Nano Aquity UPLC,美国Waters公司;LC-ESI-MS/MS,美国Thermo Fisher公司;分析软件:ClinProt Tools version 2.0,flexControl version 3.0,德国Bruker Daltonics公司;BioworksBrowser 3.3.1 SP1,美国Bioworks公司。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 MB-WCX提取血清总蛋白完全混匀磁珠悬浮液1 min,加10 μl MB-WCX结合液以及10 μl MB-WCX磁珠至PCR管,混匀。加5 μl血清样本,混匀至少5次,静置5 min。将PCR管放入磁柱分离器,使磁珠贴壁l min,液体清澈后弃上清液。加100 μl MB-WCX冲洗液,磁柱分离器上前后翻转移动10次PCR管,磁珠贴壁后弃上清液。加5 μl MB-WCX洗脱液洗涤贴壁的磁珠,并反复吹打10次,磁珠贴壁2 min,将上清液移入干净的离心管。加5 μl MB-WCX稳定液至离心管并混匀,提取的蛋白多肽用于直接质谱检测或者冻存于-20℃冰箱24 h之内质谱分析。

1.2.2 MALDI-TOF质谱分析分离收集得到的蛋白样本1 μl与10 μl的基质α-氰基-4-羟基肉桂酸混匀,取1 μl点在Anchorchip靶板上,每个样本重复点三个复孔。室温干燥后将靶板放入质谱仪进行飞行时间质谱分析,采用FlexContro1 3.0软件进行标准品校正后开始样本检测,每个样本要共300次激光打靶(5次点靶,每次打靶2×30次)生成质谱图,获得由不同质核比(mass-to-charge ratio, m/z)组成的蛋白多肽图谱。ClinProt Tools version 2.0进行数据分析。

1.2.3 LC-ESI-MS/MS多肽鉴定原始样品加20 μl流动相A,转移至进样瓶中,捕集流速15 μl/min,捕集时间3 min,分析流速400 nl/min,分析时间60 min,色谱柱温度35℃,Partial Loop模式进样,进样体积18 μl。梯度洗脱,Nano离子源,喷雾电压1.8 kV,质谱扫描时间60 min,实验模式为数据依赖(Data Dependent)及动态排除(Dynamic Exclusion),在10秒内对母离子进行2次串级之后加入到排除列表内90秒,扫描范围400~2 000 m/z,一级扫描(MS)使用Obitrap,分辨率设定为100 000,CID及二级扫描使用LTQ,在MS谱图中选取强度最强的10个离子的单一同位素作为母离子进行MS/MS(单电荷排除,不作为母离子)。使用数据分析软件BioworksBrowser 3.3.1 SP1进行SequestTM检索,检索数据库为uniProt。母离子误差设定为100 ppm,碎片离子误差设为1Da,酶切方式为非酶切,可变修饰为M(Methionine)甲硫氨酸氧化,固定酶切Carbamidomethyl。检索结果参数设定为deltacn≥0.10,两电荷Xcorr 2.6,三电荷Xcorr 3.1,三电荷以上Xcorr 3.5。

1.3 统计学方法所有样本采用盲法检测和分析。FlexControl version 3.0软件分析质谱数据,标准参照为1~10 kDa的多肽和蛋白混合物。ClinProt Tools 2.0分析多肽表达模式,包括差异峰的选择、计算。GA算法建立诊断模型,ClinProt Tools 2.0验证模型的敏感度及特异性。计量数据用(x±s)表示,P < 0.01为差异有统计学意义。

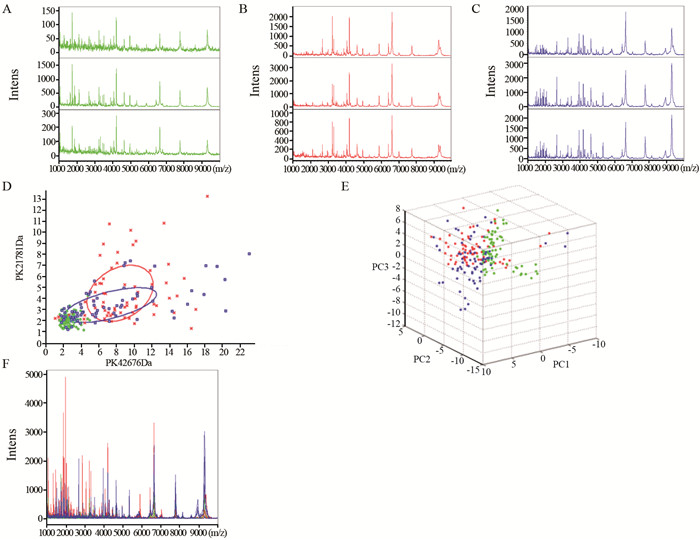

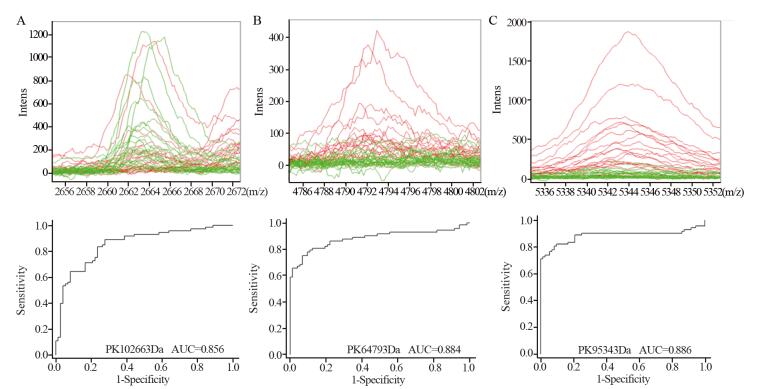

2 结果 2.1 结直肠正常对照组与结直肠癌组血清蛋白组表达差异MALDI-TOF质谱图提示正常对照(绿)、结直肠癌术前(红)及术后(蓝)组血清质谱组内有很好的稳定性和重复性,见图 1A~C。主成份分析二元图及三维图结果能够区分正常对照与结直肠癌患者,图 1D~E。在1至10 kDa范围内,正常对照、结直肠癌术前及术后组间蛋白峰有较明显差异,图 1F。ClinProt软件分析共发现80个差异表达峰,与正常对照组相比,其中12个(结直肠癌血清中9个差异峰高表达,3个差异峰低表达)差异具有统计学意义(均P < 0.01),见表 1。

|

| A: mass spectra of CRTL group; B: mass spectra of pre-operation of CRC group; C: mass spectra of post-operation of CRC group; D: bivariate plot of CRTL, pre-and post-operation of CRC group; E: 3D plot of CRTL, pre-and post-operation of CRC group; F: mass spectra of CRTL, pre-and post-operation of CRC group 图 1 结直肠正常对照组和结直肠癌术前及术后组患者血清质谱对比 Figure 1 Comparison of serum proteomics profile among normal control(CRTL), pre- and post-operation colorectal cancer(CRC) groups |

|

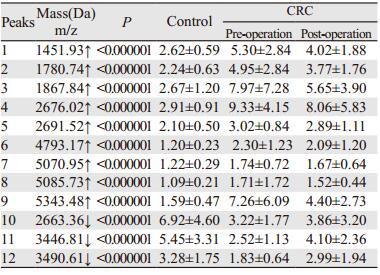

GA分析建立诊断模型,该模型包括3个差异表达峰,分别为m/z: 2663.36、m/z: 4793.17和m/z: 5343.48,其诊断结直肠的敏感度及特异性分别为99.31%和96.49%。正常对照(绿)及结直肠癌术前(红)患者质谱在m/z: 2663.36、m/z: 4793.17和m/z: 5343.48的差异明显,其受试者特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic, ROC),见图 2,曲线下面积(area under the curve, AUC)分别为0.85559、0.88356和0.88585。独立样本双盲验证该模型对结肠癌诊断的敏感度及特异性分别88.33%(53/60)和85.00%(51/60),Youden指数为73.33。

|

| A: mass spectra and ROC curve of pre-operation CRC and CRTL groups at m/z: 2663.6; B: mass spectra and ROC curve of pre-operation CRC and CRTL groups at m/z: 4793.17; C: mass spectra and ROC curve of pre-operation CRC and CRTL groups at m/z: 5343.48 图 2 m/z: 2663.36、m/z: 4793.17和m/z: 5343.48处正常对照、结直肠癌患者术前血清质谱 Figure 2 Mass spectra of CRTL and pre-operation CRC groups at m/z: 2663.6, m/z: 4793.17 and m/z: 5343.48 |

LC-ESI-MS/MS鉴定m/z: 2663.36、m/z: 4793.17和m/z: 5343.48的多肽序列分别为A.DEAGSEADHEGTHSTKRGHAKSRPV.R、Y.DMFVHPRFGPIKCIRTLRAVEA DEELTVAYGYDHSPPGKSGPE.A和G.AAYEDFNIQLRRSQESAAPTLSRVLMKV DGVVIQLTKGSVLVNGHPVLL.P,其对应的蛋白分别为纤维蛋白原α前体亚型1(FGA)、组蛋白赖氨酸甲基转移酶SETD7(SETD7)和黏蛋白5AC(MUC5AC)。

3 讨论早期诊断后接受手术治疗者5年生存率可达90%以上,而晚期患者5年生存率仅10%左右[14]。因此,早期诊断对结直肠癌患者的生存和预后至关重要。结直肠癌的发生发展是一个多阶段的病理过程,一般来说,大约需要5~10年,这为结直肠癌的早期诊断和治疗提供了时间窗[15]。

目前结直肠癌的筛查和诊断手段包括粪便潜血、影像学、肠镜等,但粪便潜血及影像学检测敏感度及特异性较差,而肠镜作为侵入性检查方法往往不易被接受[16]。血清标本能够实时动态的反映机体生理及病理状态,且容易获得,但血清CEA的敏感度及特异性相对偏低,在健康个体中的波动较大,研究发现其在同一个体的变异达30%,导致其在筛查无症状人群及诊断结直肠癌方面的价值存在争议[17]。

近年来研究者利用蛋白组学技术寻找结直肠癌的血清标志物发现了对结直肠癌早期诊断有价值的蛋白,如脂围蛋白(perilipin-2)[18]、激肽原-1(kininogen-1)[19]等。但目前尚未发现可以应用于临床的结直肠癌特异的血清标志物,这可能与以下因素有关:肿瘤的异质性、研究设计、标本类型、样本的收集和选择、质谱研究工具的敏感度和特异性以及缺乏有效的验证策略[20]。本研究的所有标本均采集于未接受过抗肿瘤治疗、无明显的活动性炎性反应及慢性代谢性疾病的个体,避免非荷瘤因素对研究结果的影响,MB-WCX联合MALDI-TOF质谱较既往色谱分离纯化、二维电泳、弱阳离子芯片及SELDI-TOF-MS等技术对样本蛋白的纯化效率更高,检测敏感度及特异性更好。

我们研究发现结直肠癌患者与正常对照者血清中存在80个差异表达峰,12个峰的差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.01),其中9个在结直肠癌术前组中高表达,3个低表达,提示结直肠癌患者与正常对照者血清质谱存在明显差异;值得注意的是,这12个差异峰在结直肠癌术后组表达趋于正常水平,进一步提示这些差异表达峰与肿瘤存在的相关性;通过GA算法建立结直肠癌的血清诊断模型,其区分结直肠癌与正常对照的敏感度及特异性分别为99.31%和96.49%;其中在3个差异表达峰(m/z: 2663.36、m/z: 4793.17、m/z: 5343.48)处诊断结直肠癌患者的AUC分别为0.85559、0.88356和0.88585,独立样本盲法验证该模型对结直肠癌诊断的敏感度及特异性分别为88.33%(53/60)和85.00%,提示该诊断模型有较高的敏感度和特异性。

LC-ESI-MS/MS鉴定3个差异峰分别为FGA、SETD7和MUC5AC。FGA是一种由肝脏合成的具有凝血功能的蛋白质,是纤维蛋白的前体,蛋白组学相关研究发现FGA在肿瘤和正常个体中存在显著差异[21-22]。SETD7含有催化结构域SET结构域,以甲硫氨酸为底物,使组蛋白H3K4甲基化[23-24],文献报道其与肿瘤的发生有关[25]。MUC5AC由黏膜上皮细胞生成并分泌,形成黏膜的保护屏障,研究发现其对结直肠癌[26]、胰腺癌[27]、肺癌[28]以及胆囊癌[29]等肿瘤的诊断和预后具有重要意义。

综上所述,我们运用血清蛋白质谱研究发现结直肠癌及正常对照蛋白表达差异明显,血清质谱诊断模型能够准确的区分正常对照与结直肠癌患者,FGA、SETD7及MUC5AC有望成为结直肠癌血清学标志物。但本研究存在不足之处:我们仅研究了结直肠癌手术前后与正常对照血清蛋白表达的差异,并在此基础上鉴定了3个差异表达蛋白,未与目前临床常用的血清学标志物CEA进行对比分析,未根据肿瘤的病理分型、分期以及同一个体疾病不同阶段做进一步研究,尚未用其他定量的方法在血清和组织中验证,因此,其临床意义有待进一步研究证实。

| [1] | Favoriti P, Carbone G, Greco M, et al. Worldwide burden of colorectal cancer: a review[J]. Updates Surg, 2016, 68(1): 7–11. DOI:10.1007/s13304-016-0359-y |

| [2] | Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer[J]. Cancer, 2014, 120(9): 1290–314. DOI:10.1002/cncr.28509 |

| [3] | Cuzick J. Statistical controversies in clinical research: long-term follow-up of clinical trials in cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2015, 26(12): 2363–6. |

| [4] | Yang J, Xiong X, Liu S, et al. Identification of novel serum peptides biomarkers for female breast cancer patients in Western China[J]. Proteomics, 2016, 16(6): 925–34. DOI:10.1002/pmic.v16.6 |

| [5] | Liu F, Zhang Y, Men T, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of gastric cancer tissue reveals novel proteins in platelet-derived growth factor b signaling pathway[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(13): 22059–75. |

| [6] | Morales-Betanzos CA, Lee H, Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, et al. Quantitative mass spectrometry analysis of PD-L1 protein expression, N-glycosylation and expression stoichiometry with PD-1 and PD-L2 in human melanoma[J]. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2017, 16(10): 1705–17. DOI:10.1074/mcp.RA117.000037 |

| [7] | Yu J, Li X, Zhong C, et al. High-throughput proteomics integrated with gene microarray for discovery of colorectal cancer potential biomarkers[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(46): 75279–92. |

| [8] | Mori K, Toiyama Y, Otake K, et al. Proteomics analysis of differential protein expression identifies heat shock protein 47 as a predictive marker for lymph node metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer[J]. Int J Cancer, 2017, 140(6): 1425–35. DOI:10.1002/ijc.30557 |

| [9] | Uzozie AC, Selevsek N, Wahlander A, et al. Targeted proteomics for multiplexed verification of markers of colorectal tumorigenesis[J]. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2017, 16(3): 407–27. DOI:10.1074/mcp.M116.062273 |

| [10] | 韩军, 何震, 董小刚, 等. 结直肠癌前哨淋巴结转移相关蛋白的蛋白组学研究[J]. 中华实验外科杂志, 2012, 29(2): 202–5. [ Han J, He Z, Dong XG, et al. Proteomics research of early metastasis-associated proteins in sentinel lymph nodes of colorectal cancer[J]. Zhonghua Shi Yan Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 29(2): 202–5. ] |

| [11] | 刘清银, 李明, 涂斌, 等. 应用磁珠联合质谱技术建立结直肠癌血清差异蛋白诊断模型[J]. 肿瘤防治研究, 2015, 42(8): 801–5. [ Liu QY, Li M, Tu B, et al. Serum peptidome patterns of colorectal cancer based on magnetic bead separation and mass-spectrometry technique[J]. Zhong Liu Fang Zhi Yan Jiu, 2015, 42(8): 801–5. ] |

| [12] | Fan NJ, Chen HM, Song W, et al. Macrophage mannose receptor 1 and S100A9 were identified as serum diagnostic biomarkers for colorectal cancer through a label-free quantitative proteomic analysis[J]. Cancer Biomark, 2016, 16(2): 235–43. DOI:10.3233/CBM-150560 |

| [13] | Yamamoto T, Kudo M, Peng WX, et al. Identification of aldolase A as a potential diagnostic biomarker for colorectal cancer based on proteomic analysis using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue[J]. Tumour Biol, 2016, 37(10): 13595–606. DOI:10.1007/s13277-016-5275-8 |

| [14] | Gao Y, Wang J, Zhou Y, et al. EValuation of serum CEA, CA199, CA724, CA125 and ferritin as diagnostic markers and faclors of clinical parameters for colorectal cancer[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 2732–45. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-21048-y |

| [15] | Søreide K, Nedrebø BS, Knapp JC, et al. Evolving molecular classification by genomic and proteomic biomarkers in colorectal cancer: potential implications for the surgical oncologist[J]. Surg Oncol, 2009, 18(1): 31–50. DOI:10.1016/j.suronc.2008.06.006 |

| [16] | Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Macrae F, et al. Improving adherence to colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines: results of a randomised controlled trial[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 106. DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3095-x |

| [17] | Saito G, Sadahiro S, Kamata H, et al. Monitoring of Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels after Curative Resection of Colon Cancer: Cutoff Values Determined according to Preoperative Levels Enhance the Diagnostic Accuracy for Recurrence[J]. Oncology, 2017, 92(5): 276–82. DOI:10.1159/000456075 |

| [18] | Matsubara J, Honda K, Ono M, et al. Identification of adipophilin as a potential plasma biomarker for colorectal cancer using label-free quantitative mass spectrometry and protein microarray[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2011, 20(10): 2195–203. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0400 |

| [19] | Wang J, Wang X, Lin S, et al. Identification of kininogen-1 as a serum biomarker for the early detection of advanced colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e70519. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070519 |

| [20] | Panis C, Pizzatti L, Souza GF, et al. Clinical proteomics in cancer: Where we are[J]. Cancer Lett, 2016, 382(2): 231–9. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.014 |

| [21] | Fish RJ, Neerman-Arbez M. Fibrinogen gene regulation[J]. Thromb Haemost, 2012, 108(3): 419–26. |

| [22] | Kopyta I, Niemiec P, Balcerzyk A, et al. Fibrinogen alpha and beta gene polymorphisms in pediatric stroke-Case-control and family based study[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2015, 19(2): 176–80. DOI:10.1016/j.ejpn.2014.11.011 |

| [23] | Herz HM, Garruss A, Shilatifard A. SET for life: biochemical activities and biological functions of SET domain-containing proteins[J]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2013, 38(12): 621–39. DOI:10.1016/j.tibs.2013.09.004 |

| [24] | Keating ST, El-Osta A. Transcriptional regulation by the Set7 lysine methyltransferase[J]. Epigenetics, 2013, 8(4): 361–72. DOI:10.4161/epi.24234 |

| [25] | Akiyama Y, Koda Y, Byeon SJ, et al. Reduced expression of SET7/9, a histone mono-methyltransferase, is associated with gastric cancer progression[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(4): 3966–83. |

| [26] | Betge J, Schneider NI, Harbaum L, et al. MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in colorectal cancer: expression profiles and clinical significance[J]. Virchows Arch, 2016, 469(3): 255–65. DOI:10.1007/s00428-016-1970-5 |

| [27] | Sierzega M, Mlynarski D, Tomaszewska R, et al. Semiquantitative immunohistochemistry for mucin (MUC1, MUC2, MUC3, MUC4, MUC5AC, and MUC6) profiling of pancreatic ductal cell adenocarcinoma improves diagnostic and prognostic performance[J]. Histopathology, 2016, 69(4): 582–91. DOI:10.1111/his.2016.69.issue-4 |

| [28] | Kim YK, Shin DH, Kim KB, et al. MUC5AC and MUC5B enhance the characterization of mucinous adenocarcinomas of the lung and predict poor prognosis[J]. Histopathology, 2015, 67(4): 520–8. DOI:10.1111/his.2015.67.issue-4 |

| [29] | Xuan J, Li J, Zhou Z, et al. The diagnostic performance of serum MUC5AC for cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2016, 95(24): e3513. |

2018, Vol. 45

2018, Vol. 45