文章信息

- 同期调强放疗联合内分泌治疗对局部晚期前列腺癌乏力症状的影响

- Effect of Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy Combined with Hormonal Therapy on Fatigue in Patients with Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2016, 43(6): 502-507

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2016, 43(6): 502-507

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2016.06.014

- 收稿日期: 2015-10-18

- 修回日期: 2016-03-15

2. 350025福州,南京军区福州总医院医务部

2. Department of Medical, Fuzhou General Hospital of Nanjing Command PLA, Fuzhou 350025, China

前列腺癌是美国男性癌症发病率最高的恶性肿瘤,且在包括中国在内的发展中国家也呈现上升趋势[1-2]。手术、放疗和内分泌治疗作为主要的治疗手段,使局部晚期前列腺癌的生存率已得到很大的提高[2-4],生存质量也逐渐成为影响治疗模式的重要因素[5]。我们前期对同期放疗联合内分泌治疗的局部晚期前列腺癌患者进行长达8年的随访[6],发现乏力也是影响生存质量的重要临床症状。调查表可以作为主要的调查方式对前列腺癌患者的生存进行直观和有效的分析[7]。目前对前列腺癌放疗后的生存质量研究中并未见有关乏力症状的相关报道[6, 8-9]。本研究应用问卷调查的方法对接受同期放疗联合内分泌治疗的患者进行随访,评价该治疗模式对乏力症状的影响,初步探讨癌症相关性乏力与临床指标的关系。

1 资料与方法 1.1 病例入组条件选取2008年2月至2012年12月就诊于南京军区福州总医院、经病理组织学证实的前列腺癌患者。ECOG评分≤2分,影像学检查排除远处脏器转移,既往无肿瘤病史。且满足以下任何一项:(1) Gleason评分8~10分;(2) 血清PSA(prostate-specific antigen)≥20 ng/ml;(3) 磁共振检查提示为T3期或者T4期(肿瘤浸透前列腺包膜或者肿瘤侵犯精囊外其他邻近结构,如膀胱颈、外括约肌、直肠、提肛肌、盆壁),伴或不伴区域淋巴结转移。

1.2 放射治疗采用三维适形调强放射治疗。CT定位扫描范围从L2到坐骨下缘以下10 cm。将图像传输至治疗计划系统(CMS4.0计划系统)。根据CT扫描图像结合盆腔MR影像学检查,勾画临床肿瘤靶区(CTV),包括前列腺、精囊腺及盆腔淋巴结引流区。其中前列腺勾画全部组织及包膜,盆腔淋巴结引流区勾画参照美国放疗肿瘤协会(RTOG)盆腔预防淋巴结引流区勾画建议,同时勾画危及器官(OAR)轮廓,如直肠、膀胱、股骨头、PTV(planning target volume)以外的肠腔、阴茎球部。PTV为CTV前上下左右均匀外扩0.5 cm,后外方向扩0.3 cm。盆腔淋巴结GTV的勾画标准为短径≥1.0 cm。物理师按要求为每例患者制定治疗计划,全部计划经组织非均匀性校正,处方剂量72.6 Gy,2.2 Gy/f,1次/天,5次/周,共33次;盆腔淋巴结引流区预防照射处方剂量为1.7 Gy/f,共33次,总剂量为56.1 Gy。要求95%PTV体积接受100%以上的处方照射剂量,直肠、膀胱均为V70≤25%,双侧股骨头V50≤5%,耻骨V70≤25%。

1.3 内分泌治疗在放疗第1天联合应用口服康士德50毫克/次,每日1次,皮下注射诺雷德3.6 mg,每28天1次,持续30月。

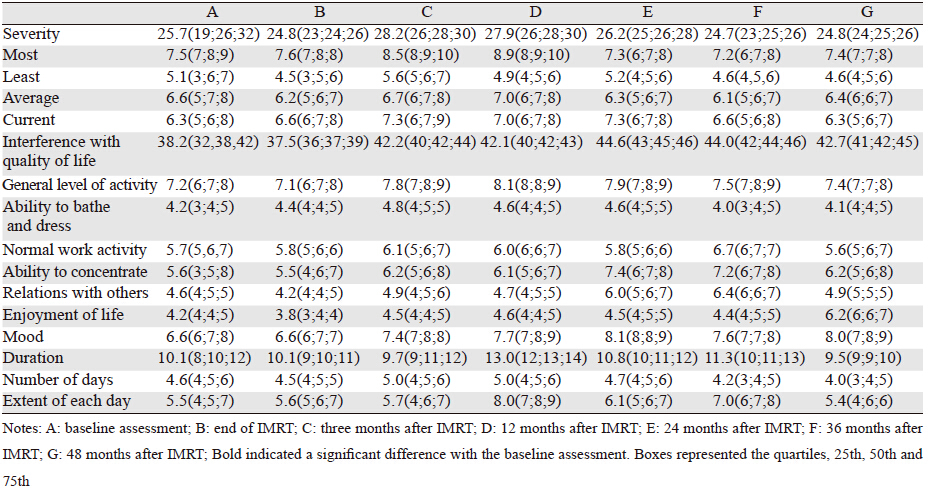

1.4 疲乏症状调查采用FSI量表(Fatigue Symptom Inventory,FSI)进行评分[10]。问卷调查的内容共13条,有包括近1周疲劳程度、对生存质量影响程度、疲劳持续时间3个维度。疲劳程度要求对近1周来自我感觉最严重、最轻、平均程度和现在的疲劳程度4个项目进行评分。对生存质量影响程度包括近1周疲劳对日常活动、洗漱、工作、注意力、与他人交往、娱乐活动和情绪等7个方面的影响进行评分。疲劳持续时间包括疲劳的天数和平均每天疲劳的时间。得分越高表示疲劳越严重。问卷调查时间采集点包括,治疗前(时间A)、放疗结束当天(时间B)、放疗结束后3月(时间C)、放疗结束后12月(时间D)、放疗结束后24月(时间E)、放疗结束后36月(时间F)、放疗结束后48月(时间G)。

1.5 问卷调查方法及数据脱落处理在时间点A、B和C,由医生和患者共同完成。其余时间观察点均通过信件方式进行随访,如果在4周内未收到回信,则由医生通过电话方式填写问卷。问卷的每个维度至少有一项得分,否则予以剔除;随访期间出现脏器转移、生化复发、失访或者死亡,病例予以脱落;全部完成题组的问卷以实际得分计算相应维度的得分;部分完成题组的问卷则以平均分计算相应维度的得分。

1.6 统计学方法运用SPSS13.0软件,临床资料以均值±标准差表示,FSI问卷调查表中所有维度的得分以均值表示,用卡方检验验证正态性分布;描述性t检验检测组间差异性;以时间点A为参照对象,评价各个维度的变化,Wilcoxon rank-sum test用于比较单一样本的变化率;各个时间点的得分与时间点A的得分组间比较用Mann-Whitney test。GraphPad Prism5绘制折线图。Logistic多分类回归模型评价癌症相关性乏力与相关影响因素的关系。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

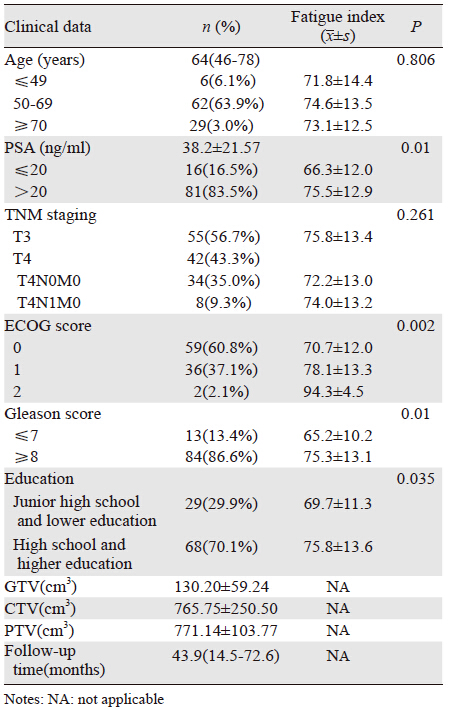

2 结果 2.1 一般资料和问卷调查情况共有126例符合纳入标准的前列腺癌患者收住入院,其中97例(76.9%)患者同意参加长期的随访问卷调查。入组患者的一般资料及放疗计划相关数据,见表 1。中位随访时间43.9月(14.5~72.6月)。所有患者均顺利完成治疗。各个时间点随访有效问卷数:时间点A和B均为97份;时间点C(95份):2例骨转移;时间点D(86份):5例生化复发,失访2例,2例死亡;时间点E(74份):3例生化复发,失访6例,死亡1例,远处转移2例;时间点F(63份):2例生化复发,失访4例,死亡5例;时间点G(61份):失访1例,骨转移1例。

|

基线评价中,有关年龄的3个组别中(≤49、50~69、≥70)未体现出差异(P>0.05);Ⅲ期、Ⅳ期的乏力评分差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);PSA>20 ng/ml组的乏力指数高于PSA≤20 ng/ml组,乏力与PSA水平相关;ECOG评分越高,乏力指数越高,且差异存在统计学意义(P<0.05),ECOG评分与乏力呈正相关;Gleason评分越高、文化程度越高,乏力指数越高,见表 1。

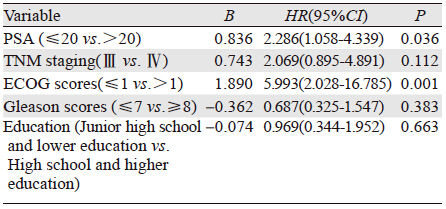

2.3 Logistic多分类回归模型将PSA水平、TNM分期、ECOG评分、Gleason评分及文化程度纳入Logistic多分类回归模型中,结果显示PSA水平和ECOG评分是影响癌症相关性乏力的独立危险因素,见表 2。

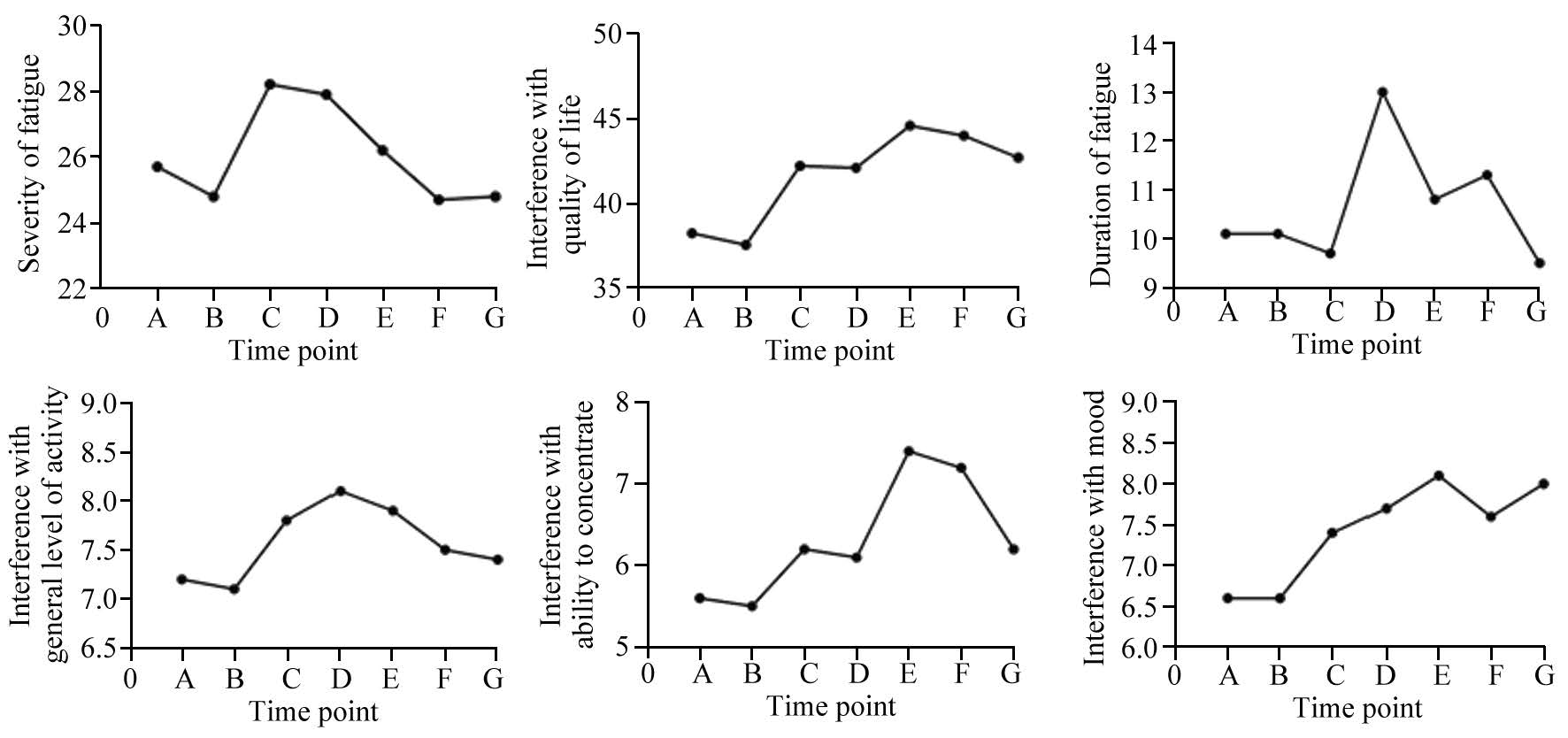

三个评价维度中,疲劳程度在随访时间点未出现明显变化,但疲劳最严重的时间主要集中在第3月和第12月。对生活影响维度中,在放疗后第3月,至随访结束,均出现不同程度的加重,且与基线比较差异均有统计学意义;在该维度的子项目中,对日常活动影响最大的主要为放疗后12月至内分泌治疗结束;放疗结束后至内分泌治疗结束,情绪和注意力均出现下降;内分泌治疗结束的各个时间点对工作、社会及娱乐方面均有影响。在整个随访期间,洗漱方面并未出现波动。疲劳持续时间波动最大的为12月至36月;疲劳天数在各个随访点未体现出差异,见表 3。各个维度、子维度中的日常活动影响积分、注意力影响积分和情绪影响积分在不同时间点的乏力积分,见图 1。

|

| 图 1 乏力评价维度积分折线图 Figure 1 Fatigue evaluation dimension integral line chart |

美国国家癌症网在2014年的《癌症相关性疲乏实践指南》中提出:癌症相关性疲劳是一种痛苦的、持续的、主观的乏力感或者疲惫感,与活动不成比例,与癌症或癌症治疗相关,常伴有功能障碍。在治疗开始阶段,就必须予以管理和评价[11]。癌症相关性乏力在肿瘤患者中发生率为50%~90%[12]。FSI量表经验证具有较好的信度和效度[13]。

因可能存在过度诊断[14],PSA不应作为年龄<50岁和年龄>75岁患者的常规检测手段,即使对老年男性有部分的生存获益[15-16]。我们研究对象的中位年龄为64岁,验证了前列腺癌好发年龄应>50岁,而且越是局部晚期年龄越高。年龄是影响前列癌发病的因素,但却与乏力无关,ECOG评分越高,乏力程度越重,这与Blackhall等[17]研究一致。这说明乏力与自身的身体机能退化无关,仅仅是主观的感受,ECOG评分从侧面验证了FSI量表的信度,而体能状况是影响生活质量的主要因素[18],及时对乏力进行评估和干预可以改善体能状况,进而提高生活质量[19]。文化程度越高,对前列腺癌的病情了解得越多,但却未深入明白疾病的发病机制及预后,这也在一定程度增加了乏力发生的可能性,而文化程度低的患者,对治疗的依从性更好,在一定程度上可减轻可能诱发乏力的思想负担。随着临床分期的增加,前列腺肿瘤负荷越大,但乏力指数的结果却未体现出差异;而在PSA水平和Gleason评分的分层结果,却存在明显差别。这与乳腺癌的乏力研究结果一致[20],与我们前期对鼻咽癌的乏力研究结果相反[21]。内分泌治疗相关肿瘤的乏力可能与激素水平紊乱有关,造成炎性调节因子失调,过多的释放炎性因子作用于神经系统内分泌系统,从而导致乏力的发生[22]。而实体瘤肿瘤可能与肿瘤负荷变化引起的一系列机体生理反应有关。我们前期研究发现在同期放化疗后的第1年,激素功能水平是影响生活质量的主要因素[6],推断雄激素水平的下降会加重乏力的程度。有关研究证实炎症释放因子(白介素1β、白细胞介素6和肿瘤坏死因子)与乳腺癌和前列腺癌的癌症相关性乏力有关[23-24]。因此对于内分泌治疗相关肿瘤,我们认为癌症相关性乏力与人体免疫系统中炎性因子的增加和皮质醇水平的调节失衡相关[25]。

60%~100%的癌症患者有不同程度的乏力症状,正在进行积极抗肿瘤治疗的患者发生率更高[26]。目前对于癌症相关性乏力的研究比较系统地集中在乳腺癌[27]、肺癌等,且大宗临床研究或者荟萃分析的主题是如何治疗[28-29]。因其机制尚不明确,治疗主要分为药物性干预和非药物性干预,药物性干预主要有:中枢兴奋剂、西洋参、促甲状腺诉释放素等[30-32]。非药物性干预主要有增加运动和心理干预[33-34]。而对前列腺癌相关性乏力的相关报道甚少,尤其是乏力相关症状对生活质量的影响研究更少。为了探讨乏力对局部晚期前列腺癌接受同期放疗联合内分泌治疗造成生活质量的影响,我们在各个研究时间节点,进行具体内容的问卷调查。疲劳程度上在各个时间点无明显变化,但是疲劳的最严重程度在治疗结束后第3月、第12月影响最大。对生活影响的程度在治疗后12月,直至随访结束,都严重困扰着纳入患者。因疾病治疗自身的原因、内分泌治疗后睾酮达到去势水平后引起的激素功能紊乱,造成纳入对象在日常活动、注意力和情绪方面出现波动。采用间断性内分泌治疗相比持续内分泌治疗,似乎能够获得更好的生存质量,包括情感方面等[35]。是否同期调强放射治疗联合间断性内分泌治疗,可带来乏力方面改善,包括乏力量表中子项目的变化,还需更多的临床数据来支持。我们的研究发现乏力影响生活质量主要体现现在日常活动、注意力和情绪3个子项目上。

综上,FSI量表主要是反映过去一周内乏力对生活质量产生的影响情况,时效性差,因随访时间点有限,在前列腺癌长期生存过程当中,无法非常准确地对乏力进行评估;FSI量表子项目只对乏力的具体影响方面进行评分,未能正确将乏力进行分层;随访48月后,共有127例问卷未完整填写,这对乏力的评价造成误差。对于ECOG评分高、Gleason>8分、PSA>20 ng/ml、且文化程度高的局部晚期前列腺癌患者,在接受同期放疗联合内分泌治疗后,要关注乏力对生活质量产生的影响,特别是日常活动、注意力和情绪方面。

| [1] | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2015[J]. CACancer J Clin, 2015, 65 (1) : 5–29. |

| [2] | American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures[M]. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2014 . |

| [3] | Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. Long-term quality-oflifeoutcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: theScandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomised trial[J]. LancetOncol, 2011, 12 (11) : 891–9. |

| [4] | Luo HC, Cheng HH, Lin GS, et al. IMRT combined with EndocrineTherapy for Intermediate and Advanced Prostate Cancer: LongtermOutcome of Chinese Patients[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2013, 14 (8) : 4711–5. |

| [5] | Penson DF, Litwin MS. Quality of life after treatment for prostatecancer[J]. Curr Urol Rep, 2003, 4 (3) : 185–95. |

| [6] | Luo HC, Cheng LP, Cheng HH, et al. Long-term quality of life outcomes in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer after intensity-modulated radiotherapy combined with and rogende privation[J]. Med Oncol, 2014, 31 (6) : 991. |

| [7] | Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors[J]. NEngl J Med, 2008, 358 (12) : 1250–61. |

| [8] | Mendenhall NP, Hoppe BS, Nichols RC, et al. Five-year out comesfrom 3 prospective trials of image-guided proton therapy forprostate cancer[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2014, 88 (3) : 596–602. |

| [9] | Clemente S, Nigro R, Oliviero C, et al. Role of the technical aspects of hypofractionated radiation therapy treatment of prosta tecancer: A revies[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2015, 91 (1) : 182–95. |

| [10] | Ham DN, Jacobsen PB, Azzarelb LM, et al. Measurement offatigue in cancer patients development and valilation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory[J]. Qual Life Res, 1998, 7 (4) : 301–10. |

| [11] | NCCN.Clinical Practice Guidelines.Cancer-Related Fatigue.Version 1.2014 [EB/OL]. [2015-01-25]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/fatigue.pdf. |

| [12] | Compos MH, Hassan BJ, Riechelmann R, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: a practical review[J]. Ann Oncol, 2011, 22 (6) : 1273–9. |

| [13] | Hann DM, Denniston MM, Baker F. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients further validation o f the fatigue symptom inventory[J]. Qual Life Res, 2000, 9 (7) : 847–54. |

| [14] | Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: importance of methods and context[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2009, 101 (6) : 374–83. |

| [15] | Howard DH, Tangka FK, Guy GP, et al. Prostate cancer screening in men ages 75 and older fell by 8 percentage points after Task Force recommendation[J]. Health Aff(Millwood), 2013, 32 (3) : 596–602. |

| [16] | Drazer MW, Prasad SM, Huo D, et al. National trends in prostate cancer screening among older American men with limited 9-year life expectancies: evidence of an increased need for shared decision making[J]. Cancer, 2014, 120 (10) : 1491–8. |

| [17] | Blackhall L, Petroni G, Shu J, et al. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of modifanal for cancer-related fatigue[J]. J Palliat Med, 2009, 12 (5) : 433–9. |

| [18] | Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler JA, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2012, 7 (1) : 64–70. |

| [19] | Dhillon HM, Ploeg HP, Bell ML, et al. The impact of physical activity on fatigue and quality of life in lung cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial protocol[J]. BMC Cancer, 2012, 12 : 572. |

| [20] | Noal S, Levy C, Hardouin A, et al. One-year longitudinal study of fatigue, cognitive functions, and quality of life after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011, 81 (3) : 795–803. |

| [21] | Luo HC, Cheng HH, Lin GS. A clinical study of cancer-related fatigue syndrome in nasopharyngeal neoplasms[J]. Lin Chuang Zhong Liu Xue Za Zhi, 2011, 16 (11) : 1006–8. [骆华春, 程惠华, 林贵山. 鼻咽癌癌症相关性乏力症状的临床研究[J]. 临床肿瘤学杂志,2011, 16 (11) : 1006–8. ] |

| [22] | Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, et al. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism?[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29 (26) : 3517–22. |

| [23] | Fernando AF, Felipe MC.Effect of chemotherapy on fatigue and presence of TNF- in breast cancer patients[C/OL]//49th American Society of Clinical Oncolgy Annual Meeting,Chicago,2013 [2013-06-05]. http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/31/15_suppl/e20601. |

| [24] | Sriram Y, Cindy C. Multimodal therapy for the treatment of fatigue in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy and radiation[C/OL]//49th American Society of Clinical Oncolgy Annual Meeting,Chicago,2013[2013-06-05]. http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/31/15_suppl/TPS9650. |

| [25] | Barton DL, Liu H, Dakhil SR, et al. Phase Ⅲ evaluation of American ginseng( panax quinquefolius) to improve cancerrelated fatigue:NCCTG trial N07C2[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2013, 105 (16) : 1230–8. |

| [26] | De Waele S, Van Belle S. Cancer-related fatigue[J]. Acta Clin Belg, 2010, 65 (6) : 378–85. |

| [27] | Alexander S, Minton O, Andrews P, et al. A comparison of the characteristics of disease-free breast cancer survivors with or without cancer-related fatigue syndrome[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2009, 45 (3) : 384–92. |

| [28] | Senior HE, Mitchell GK, Nikles J, et al. Using aggregated single patient(N-of-1) trials to determine the effectiveness of psychostimulants to reduce fatigue in advanced cancer patients : a rationale and protocol[J]. BMC Palliat Care, 2013, 12 (1) : 17. |

| [29] | Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Brillant C, et al. Recombinant human erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality in patients with cancer: a meta-analysisi of randomized trials[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373 (9674) : 1532–42. |

| [30] | Senior HE, Mitchell GK, Nikles J, et al. Using aggtegated single patient(N-of-1) trials to determine the dffectiveness of paychostimulants to reduce fatigue in advanced cancer patients: a rational and protocol[J]. BMC Palliat Care, 2013, 12 (1) : 17. |

| [31] | Barton DL, Soori GS, Bauer BA, et al. Pilot study of Panax quinquefolius(American ginseng) to improve acncer-related fatigue: a randomized ,double-blind, dose-finding evaluation: NCCTG trial N03CA[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2010, 18 (2) : 179–87. |

| [32] | Khomane KS, Meena CL, Jain R, et al. Novel thyrotropinreleasing hormone analogs: a patent review[J]. Expert Opin Ther Pat, 2011, 21 (11) : 1673–91. |

| [33] | Puetz TW, Herring MP. Differential effects of exercise on cancerrelated fatigue during and following treatment: a meta-analysis[J]. Am J Prev Med, 2012, 43 (2) . |

| [34] | Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, et al. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors-a meta-analysis[J]. Psychooncology, 2011, 20 (2) : 115–26. |

| [35] | Hussain M, Tangen CM, Berry DL, et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368 (14) : 1314–25. |

2016, Vol. 43

2016, Vol. 43