泌尿系统感染(urinary tract infection,UTI)是肾移植术后最常见的感染[1],发病率可达35.0%至79.0%[2-4],其中移植后第一年UTI的发病率达74.0%(81.9%发生于术后3个月内),第二年为35.7%,第四年为21.5%[5]。导致肾移植术后UTI高发的相关因素包括高龄、女性、免疫抑制剂的使用、供肾类型、原发肾病、泌尿系统解剖学异常等[5-8]。UTI反复发作可严重影响移植肾功能和肾移植受者预后 [9]。

肾移植受者与普通患者UTI的特点不尽相同。本文旨在比较肾移植受者与普通患者UTI的症状、复发、病原体种类及其药敏结果等方面的差异,进而探究肾移植受者UTI个体化诊治方案。

1 对象与方法 1.1 对 象采用回顾性分析方法,选择南方医院肾移植科2003年1月至2014年8月间完成肾移植并坚持随访的肾移植受者734例,术后确诊UTI且中段尿培养阳性、病原体种类确定患者49例。

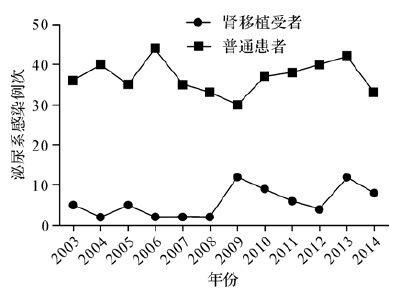

按随机数表法[10]对南方医科大学南方医院同期诊断为UTI且中段尿培养阳性、病原体种类确定的13 023例普通患者进行随机取样,共取得490例患者,选取其中401例病历资料完整的患者作为对照组。诊断为UTI但中段尿培养阴性、培养污染、病原体种类不确定或病历资料不全的患者不纳入研究。肾移植受者术前UTI不纳入本研究。两组患者收治时间分布如图 1所示。

|

| 图 1 肾移植受者与普通患者泌尿系统感染例次的时间分布 Fig. 1 Number of kidney transplantation recipients and non-recipients with UTI,by years |

UTI诊断标准参见2009年美国感染疾病协会国际临床实践指南[11]。UTI复发定义:UTI经治疗后症状消失、尿菌转阴,在6周内再次出现菌尿,菌种与上次相同且为同一血清型[12]。药敏试验结果判定参见美国国家临床实验室标准委员会(NCCLS)2014年标准[13]。药物敏感率=对某药敏感的微生物个数/行该药物敏感试验的同种微生物总数×100%,耐药率=对某药耐药的微生物个数/行该药物敏感试验的同种微生物总数×100%,体质指数(BMI)=体质量(kg)/身高(m)2。

1.3 统计学方法采用SPSS 17.0统计软件进行分析,呈正态分布的计量资料用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,组间比较用t检验;计数资料用百分率表示,组间比较用χ2检验。 P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结 果 2.1 两组患者一般资料及感染类型比较肾移植受者与普通患者一般人口统计学资料如表 1所示。49例肾移植受者共69次UTI,均为尸肾移植受者,女性63.3%;42例(84.6%)术前行血液透析,平均透析时间(11.00±2.14)个月,7例术前未透析;群体反应性抗体阴性患者占91.8%;术后D-J管存留时间(9.30±1.79) d,导尿留置时间(6.10±0.21) d,首次UTI距移植中位时间为7.4(0.6~149.9)个月。401例普通患者共443次UTI,女性58.6%,亦多于男性。两组患者UTI类型比较如表 2所示,肾移植受者术后UTI中无症状菌尿所占比例最高(50.7%),与普通患者(45.6%)相似;两组感染类型均无差异。

| [(x±s)或n(%)] | |||||||||||

| 组别 | n* | 年龄 | 性别 | 体质指数(kg/m2) | 高血压 | 糖尿病 | 泌尿系统基础疾病 | ||||

| 男性 | 女性 | 结石 | 畸形 | 肿瘤 | |||||||

| 肾移植受者 | 49 | 47.55±1.76 | 18(36.7) | 31(63.3) | 21.52±5.92 | 16(32.7) | 12(24.5) | 8(16.3) | 1(2.0) | 0(0) | |

| 普通患者 | 401 | 51.61±0.90 | 166(41.4) | 235(58.6) | 23.81±4.06 | 119(29.7) | 84(21.0) | 118(29.4) | 37(9.2) | 11(2.7) | |

| P值 | 0.054 | 0.531 | 0.531 | 0.080 | 0.668 | 0.568 | 0.054 | 0.088 | 0.618 | ||

| *如同一患者多次泌尿系统感染则取首次感染时的数据. | |||||||||||

| [n(%)] | |||||

| 组别 | 感染例次 | 膀胱炎 | 肾盂肾炎 | 无症状菌尿 | 类型不明 |

| 肾移植受者 | 69 | 0(0) | 1(1.45) | 35(50.72) | 33(47.83) |

| 普通患者 | 443 | 5(1.1) | 8(1.80) | 202(45.60) | 228(51.47) |

| P值 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.501 | 0.585 | |

两组患者UTI临床表现比较如表 3所示。肾移植受者尿路刺激征发生率高于普通患者,感染复发率高于普通患者(38.8%与16.7%,P<0.001,未在表中显示),而发热、肾周疼痛、排尿困难等症状发生率无差别。肾移植受者发生UTI时外周血中性粒细胞百分率高于普通患者,淋巴细胞百分率、血小板计数少于普通患者,而嗜碱性粒细胞百分率、嗜酸性粒细胞百分率、红细胞计数、单核细胞百分率均无明显差异(P>0.05)。

| [n(%)或(±s)] | ||||||||||||

| 组别 | 例次 | 尿路刺激征 | 排尿困难 | 肾周疼痛 | 发热 | 血常规 | ||||||

| 尿频 | 尿急 | 尿痛 | 中性粒细胞(%) | 红细胞(×1012/L) | 淋巴细胞(%) | 单核细胞(%) | 血小板(×109/L) | |||||

| 肾移植受者 | 69 | 30(43.8) | 30(43.8) | 25(36.2) | 2(2.9) | 2(2.9) | 26(37.7) | 72.65±1.90 | 3.81±0.09 | 17.73±1.27 | 7.30±0.48 | 187.64±10.84 |

| 普通患者 | 443 | 83(18.7) | 83(18.7) | 75(17.0) | 39(8.8) | 26(5.9) | 158(35.7) | 68.59±0.73 | 3.99±0.19 | 21.28±0.61 | 7.61±0.31 | 240.76±5.26 |

| P值 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.100 | 0.561 | 0.787 | 0.048 | 0.715 | 0.037 | 0.717 | <0.010 | |

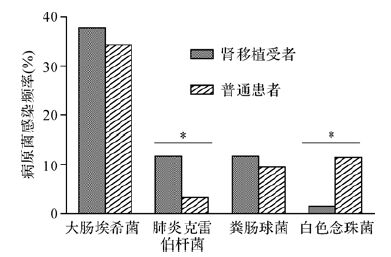

肾移植受者与普通患者病原体比较如图 2所示。两组感染频率最高的病原菌均为大肠埃希菌,分别为37.7%和34.1%,两组间无差异(P>0.05);肾移植受者肺炎克雷伯杆菌感染频率高于普通患者(P=0.001),而白色念珠菌感染频率低于普通患者(P=0.008)。

|

| *P<0.01 图 2 肾移植受者与普通患者泌尿系统感染四大病原菌的频率分析 Fig. 2 Analyses of percentages of four main types of UTI pathogens percentage between kidney transplantation recipients and non-recipients |

肾移植受者与普通患者感染病原菌药敏试验结果分析比较如表 4所示。肾移植受者大肠埃希菌对阿莫西林/克拉维酸、阿米卡星、氯霉素、庆大霉素的敏感率均高于普通患者,对氨苄西林的敏感率则低于普通患者,对氨苄西林(95.7%与54.3%,P<0.001,未在表中显示)、复方新诺明(91.7%与57.6%,P=0.002,未在表中显示)的耐药率均高于普通患者;肺炎克雷伯杆菌对庆大霉素、哌拉西林、复方新诺明、四环素的敏感率均高于普通患者;粪肠球菌对氨苄西林、呋喃妥因的敏感率高于普通患者,但对苯唑西林的敏感率低于普通患者。

| [n(%)] | |||||||||||||||

| 组别 | 大肠埃希菌 | 肺炎克雷伯杆菌 | 粪肠球菌 | ||||||||||||

| 阿莫西林/克拉维酸 | 阿米卡星 | 氨苄西林 | 氯霉素 | 庆大霉素 | 复方新诺明 | 庆大霉素 | 哌拉西林 | 复方新诺明 | 四环素 | 氨苄西林 | 呋喃妥因 | 苯唑西林 | 复方新诺明 | ||

| 肾移植受者 | 11(47.9) | 23(95.9) | 1(4.3) | 14(66.7) | 12(50.0) | 2(8.3) | 6(75.0) | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | 5(83.3) | 4(80.0) | 0(0) | 1(25.0) | |

| 普通患者 | 8(14.9) | 43(46.2) | 42(44.7) | 17(33.3) | 21(22.3) | 11(12.0) | 2(14.3) | 0(0) | 1(7.1) | 0(0) | 2(14.3) | 0(0) | 1(7.1) | 0(0) | |

| P值 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.010 | |

UTI是肾移植受者术后常见的感染。肾移植后第1个月内首发UTI多源于医院获得性感染、医源性感染或供者携带的病原菌导致的感染[14],其中医院获得性感染占32.2%[15]。本研究中有5例患者(10.2%)为肾移植术后1个月内首发UTI,均为医院获得性感染。UTI大多发生在肾移植后第6个月左右[16],本研究中肾移植受者UTI距移植中位时间为7.4个月,可能与抗生素的预防性使用为肾移植受者术后早期提供了一定的保护作用有关[17]。本研究两组患者中女性感染者相对较多,与既往研究结果相符[18]。肾移植受者UTI平均年龄与普通UTI患者相似,两组患者UTI相关危险因素(如泌尿系统畸形、结石、女性、糖尿病等)也相似,因此除移植因素外两组患者具有可比性。因每个肾移植受者均有6天左右的导尿史及D-J管留置史,而普通患者中仅30.2%患者有导尿史,因此肾移植导致的导管相关因素亦是肾移植受者与普通患者UTI差异的一个原因。

3.1 肾移植受者与普通患者UTI临床表现存在差异肾移植受者UTI时尿路刺激征更为多见,且复发率高于普通患者,这可能与肾移植受者免疫抑制状态下对病原体易感有关。肾移植受者免疫抑制剂浓度较高是UTI的高危因素[19],适时调整免疫抑制剂剂量对于肾移植受者UTI的防治至关重要。

本研究中肾移植受者UTI时外周血中性粒细胞百分率高于普通患者,淋巴细胞百分率、血小板计数少于普通患者。这可能是由于维持性免疫抑制剂主要以T细胞为靶细胞进行免疫抑制[20],导致淋巴细胞百分率降低,从而中性粒细胞百分率相对增高。而血小板计数少于普通患者,我们初步认为与免疫抑制剂的影响有关;同时血小板不仅具有凝血功能,还参与炎症反应过程[21],以及具有免疫相关性[22],因此血小板功能与肾移植受者UTI之间的关系还需要进一步研究。

3.2 肾移植受者与普通患者UTI病原体易感性不尽相同大肠埃希菌是UTI首要致病菌,可能由于泌尿系统在解剖学上临近肛周(尤其是女性),易受肠道细菌影响从而引起逆行性感染,其感染经常发生于移植后6~12周[5]。本研究中两组患者出现频率最高的病原体均为大肠埃希菌,所占比例分别为37.7%和34.1%。本研究中白色念珠菌所占比例为1.5%,与文献报道(2.0%)[23]相近,但低于普通患者;而肾移植受者UTI病原体中肺炎克雷伯杆菌所占比例高于普通患者。可见肾移植受者与普通患者UTI病原体易感性不同[24-25]。

3.3 肾移植受者与普通患者UTI病原体药物敏感率不同肾移植受者与普通患者UTI病原菌药敏结果存在诸多差别。肾移植受者UTI菌对氨基糖苷类抗生素(如阿米卡星、庆大霉素)和氯霉素的敏感率高于普通患者,可能是因为氨基糖苷类抗生素和氯霉素等肾毒性药物不常用于肾移植受者,但广泛运用于肾功能正常的普通患者,导致普通患者UTI致病菌对其耐药性增加。本研究肾移植受者易感的大肠埃希菌对氨苄西林和复方新诺明等常用抗生素的耐药率高于普通患者,这与Senger等[16]的研究结果相符。术前使用复方新诺明对预防肾移植术后卡氏肺孢子虫感染具有重要意义[26],然而已有多数细菌对复方新诺明耐药,本次研究中大肠埃希菌、肺炎克雷伯杆菌和粪肠球菌对其敏感率分别为8.3%、50.0%和25.0%,这可以解释为什么肾移植受者术后6个月内使用复方新诺明预防肺孢子菌肺炎的同时不能完全避免UTI[5],本研究36.7%肾移植UTI患者感染发生在术后6个月内。肾移植受者更易发生抗生素耐药[26],临床疑似UTI者应尽早完成中段尿培养和药敏试验,指导合理使用抗生素以减少耐药发生。

移植受者UTI中无症状性菌尿者可达85.0%[27],本研究移植受者UTI中无症状性菌尿占50.7%,接近普通患者。无症状性菌尿症可导致血肌酐升高和肾功能受损[28],但肾移植后无症状性菌尿受者接受抗生素治疗后,感染加重的风险加大,这可能是由于抗生素的过度使用导致了耐药菌的产生,从而增加了感染风险[29]。因此肾移植术后3个月以后发生的无症状性菌尿受者不建议接受治疗(除非受者血中的肌酐持续升高[30]),可行常规尿培养检测。

综上所述,本研究结果表明,肾移植受者与普通UTI患者均以女性居多,大肠埃希菌的感染频率均为最高,但两组患者UTI易感病原体不同:肾移植受者肺炎克雷伯杆菌频率高于普通患者,而白色念珠菌频率低于普通患者。肾移植受者发生UTI时尿路刺激征更为多见,更易发生抗生素耐药,感染复发率更高。早期行中段尿培养、合理使用抗生素、及时调整免疫抑制剂剂量对于肾移植受者UTI的防治具有重要意义。

| [1] | SCHMALDIENST S, DITTRICH E, HÖRL W H. Urinary tract infections after renal transplantation[J]. Curr Opin Urol, 2002, 12 (2) :125–130 . |

| [2] | RUBIN R H. Infectious disease complications of renal transplantation[J]. Kidney Int, 1993, 44 (1) :221–236 . |

| [3] | KARAKAYALI H, EMIROLU R, ARSLAN G, et al. Major infectious complications after kidney transplantation[J]. Transplant Proc, 2001, 33 (1-2) :1816–1817 . |

| [4] | GIRAL M, PASCUARIELLO G, KARAM G, et al. Acute graft pyelonephritis and long-term kidney allograft outcome[J]. Kidney Int, 2002, 61 (5) :1880–1886 . |

| [5] | PELLÉ G, VIMONT S, LEVY P P, et al. Acute pyelonephritis represents a risk factor impairing long-term kidney graft function[J]. Am J Transplant, 2007, 7 (4) :899–907 . |

| [6] | SORTO R, IRIZAR S S, DELGADILLO G, et al. Risk factors for urinary tract infections during the first year after kidney transplantation[J]. Transplant Proc, 2010, 42 (1) :280–281 . |

| [7] | ESEZOBOR C I, NOURSE P, GAJJAR P. Urinary tract infection following kidney transplantation: frequency, risk factors and graft function[J]. Pediatr Nephrol, 2012, 27 (4) :651–657 . |

| [8] | ALANGADEN G J, THYAGARAJAN R, GRUBER S A, et al. Infectious complications after kidney transplantation: current epidemiology and associated risk factors[J]. Clin Transplant, 2006, 20 (4) :401–409 . |

| [9] | SQALLI T H, LABOUDI A, ARRAYHANI M, et al. Urinary tract infections in renal allograft recipients from living related donors[J]. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl, 2008, 19 (4) :551–553 . |

| [10] | SINGH S, MAHMOOD M, TRACY D S. Estimation of mean and variance of stigmatized quantitative variable using distinct units in randomized response sampling[J]. Statistical Papers, 2001, 42 (3) :403 . |

| [11] | HOOTON T M, BRADLEY S F, CARDENAS D D, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2010, 50 (5) :625–663 . |

| [12] | SILVA C, AFONSO N, MACÁRIO F, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections in kidney transplant recipients[J]. Transplant Proc, 2013, 45 (3) :1092–1095 . |

| [13] | PATEL J B, COCKERILL Ⅲ F R, ALDER J, et al. M100-S25 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing[M]. 出版城市: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2014 : 131 -165. |

| [14] | KARUTHU S, BLUMBERG E A. Common infections in kidney transplant recipients[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012, 7 (12) :2058–2070 . |

| [15] | PAPASOTIRIOU M, SAVVIDAKI E, KALLIAKMANI P, et al. Predisposing factors to the development of urinary tract infections in renal transplant recipients and the impact on the long-term graft function[J]. Ren Fail, 2011, 33 (4) :405–410 . |

| [16] | SENGER S S, ARSLAN H, AZAP O K, et al. Urinary tract infections in renal transplant recipients[J]. Transplant Proc, 2007, 39 (4) :1016–1017 . |

| [17] | KHOSROSHAHI H T, MOGADDAM A N, SHOJA M M. Efficacy of high-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazol prophylaxis on early urinary tract infection after renal transplantation[J]. Transplant Proc, 2006, 38 (7) :2062–2064 . |

| [18] | RIVERA-SANCHEZ R, DELGADO-OCHOA D, FLORES-PAZ R R, et al. Prospective study of urinary tract infection surveillance after kidney transplantation[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2010, 10 :245 . |

| [19] | KAMATH N S, JOHN G T, NEELAKANTAN N, et al. Acute graft pyelonephritis following renal transplantation[J]. Transpl Infect Dis, 2006, 8 (3) :140–147 . |

| [20] | HORIGOME A, HIRANO T, OKA K. Tacrolimus-induced apoptosis and its prevention by interleukins in mitogen-activated human peripheral-blood mononuclear cells[J]. Immunopharmacology, 1998, 39 (1) :21–30 . |

| [21] | SANTIMONE I, DI CASTELNUOVO A, DE CURTIS A, et al. White blood cell count, sex and age are major determinants of heterogeneity of platelet indices in an adult general population: results from the MOLI-SANI project[J]. Haematologica, 2011, 96 (8) :1180–1188 . |

| [22] | HERZOG B H, FU J, WILSON S J, et al. Podoplanin maintains high endothelial venule integrity by interacting with platelet CLEC-2[J]. Nature, 2013, 502 (7469) :105–109 . |

| [23] | ARIZA-HEREDIA E J, BEAM E N, LESNICK T G, et al. Impact of urinary tract infection on allograft function after kidney transplantation[J]. Clin Transplant, 2014, 28 (6) :683–690 . |

| [24] | BARBOUCH S, CHERIF M, OUNISSI M, et al. Urinary tract infections following renal transplantation: a single-center experience[J]. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl, 2012, 23 (6) :1311–1314 . |

| [25] | LINHARES I, RAPOSO T, RODRIGUES A, et al. Frequency and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria implicated in community urinary tract infections: a ten-year surveillance study (2000-2009)[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2013, 13 :19 . |

| [26] | DI COCCO P, ORLANDO G, MAZZOTTA C, et al. Incidence of urinary tract infections caused by germs resistant to antibiotics commonly used after renal transplantation[J]. Transplant Proc, 2008, 40 (6) :1881–1884 . |

| [27] | FIORANTE S, LOPEZ-MEDRANO F, LIZASOAIN M, et al. Systematic screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in renal transplant recipients[J]. Kidney Int, 2010, 78 (8) :774–781 . |

| [28] | MORADI M, ABBASI M, MORADI A, et al. Effect of antibiotic therapy on asymptomatic bacteriuria in kidney transplant recipients[J]. Urol J, 2005, 2 (1) :32–35 . |

| [29] | GREEN H, RAHAMIMOV R, GOLDBERG E, et al. Consequences of treated versus untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria in the first year following kidney transplantation: retrospective observational study[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2013, 32 (1) :127–131 . |

| [30] | PARASURAMAN R, JULIAN K. Urinary tract infections in solid organ transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2013, 13 (4) :327–336 . |