文章信息

- 孙翠翠, 张斯萌, 温倜, 曲秀娟, 刘云鹏

- SUN Cuicui, ZHANG Simeng, WEN Ti, QU Xiujuan, LIU Yunpeng

- 晚期非小细胞肺癌肿瘤生长速率与临床病理特征及预后的相关性

- Correlation between Tumor Growth Rate and Clinicopathological Features and Prognosis in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- 中国医科大学学报, 2019, 48(8): 673-677

- Journal of China Medical University, 2019, 48(8): 673-677

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2019-01-07

- 网络出版时间:2019-07-15 11:01

近年来肺癌发病率和死亡率显著增长, 现我国每年肺癌发病约78.1万人, 肺癌死亡率居我国恶性肿瘤之首[1-2]。非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC)在肺癌中占比最高且预后差, 晚期患者主要的治疗手段包括放化疗、靶向治疗以及免疫治疗等[3-4]。临床上一直应用实体肿瘤的疗效评价标准(Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, RECIST)对药物疗效进行评价, 但仍有局限性[5]。随着靶向治疗时代的到来及个体化医疗的发展, 如何找到简便、实时并精准的评价疗效和预测预后的指标, 从而量化NSCLC患者治疗后的肿瘤反应, 以预测疾病进展的生存差异, 仍是临床工作中急需解决的问题。

肿瘤生长速率(tumor growth rate, TGR)定义为1个月内肿瘤体积增加的百分比[6]。TGR的计算包含了靶病灶最大直径总和以及2次评估间隔的时间, 可对肿瘤进行动态、定量评估, 有助于临床医生确认给定药物能否控制肿瘤生长。因此, TGR可能成为评价抗肿瘤治疗是否改变疾病进程的有用工具[7]。在最新的免疫治疗中, TGR增加≥2倍为超进展的定义之一[8-9]。本研究主要探讨晚期NSCLC中TGR与临床病理特征及预后的相关性。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2014年1月至2018年3月于中国医科大学附属第一医院肿瘤内科就诊的NSCLC患者458例。纳入标准:(1)初治的局部晚期或转移性NSCLC; (2)有完整的病历资料及影像学图像; (3)预计生存期 > 3个月。排除标准:(1)行手术、放疗等局部治疗后; (2)无法明确病理类型; (3)多原发恶性肿瘤; (4)有严重基础疾病。

1.2 研究方法回顾性收集性别、年龄、吸烟史、肿瘤家族史、东部肿瘤协作组(Eastern Cooperative Group, ECOG)评分、病理类型、组织学分级、Ki-67指数、表皮生长因子受体(epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR)基因状态、肿瘤大小(T)、淋巴结转移(N)、临床分期、一线治疗方案等资料, 其中部分参数不详, 未予分析。假设肿瘤生长遵循指数定律, 通过以下公式计算TGR:TGR=100 [exp (TG)-1], 其中TG=3log (Dt/D0) /t, D0、Dt分别为基线及第1次疗效评价时靶病灶最大直径总和, t为2次肿瘤评估间隔的时间[6]。本文遵循RECIST标准测量靶病灶, 排除基线时仅存在非靶病灶(如仅有胸腔积液或骨转移)及第1次疗效评价时出现新发病灶的患者。

1.3 统计学分析数据处理使用SPSS 20.0软件, 计数资料以百分率(%)表示; TGR与临床病理特征的相关性采用Pearson χ2检验及Fisher精确概率法。采用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线, 应用log-rank比较各组生存曲线的分布差异; 利用Cox风险比例回归模型分析TGR对预后的影响。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 TGR与NSCLC临床病理特征的关系本研究共纳入458例晚期NSCLC患者, 其中男214例, 女244例; < 60岁235例, ≥60岁223例; 腺癌357例, 非腺癌101例; EGFR野生型154例, 突变型160例; Ⅲ期142例, Ⅳ期316例; 化疗组295例, 靶向治疗组163例。在治疗后进行第1次疗效评价时, 判定为部分缓解142例, 疾病稳定255例, 疾病进展61例; 至随访截止时间, 458例患者中共有375例疾病进展, 83例未进展, 进展发生率为81.9%;共有203例死亡, 255例存活, 死亡率为44.3%。利用受试者操作特征曲线找到TGR最佳截断点为-16.128 (-99.127, 283.759), 以此为界分为高TGR组和低TGR组。结果显示, TGR高低与年龄、EGFR基因状态、一线治疗方案相关, 且高TGR多见于年龄≥60岁(P = 0.038)、EGFR野生型(P = 0.013)、一线首选化疗(P = 0.002)的患者。见表 1。

| Clinicopathological feature | NSCLC (n = 458) | P | ||

| Low TGR [n (%)] | High TGR [n (%)] | Sum [n (%)] | ||

| Gender | 0.166 | |||

| Male | 126(44.2) | 88(50.9) | 214(46.7) | |

| Female | 159(55.8) | 85(49.1) | 244(53.3) | |

| Age (year) | 0.038 | |||

| < 60 | 157(55.1) | 78(45.1) | 235(51.3) | |

| ≥60 | 128(44.9) | 95(54.9) | 223(48.7) | |

| Smoking history | 0.497 | |||

| No | 151(53.0) | 86(49.7) | 237(51.7) | |

| Yes | 134(47.0) | 87(50.3) | 221(48.3) | |

| Family history | 0.856 | |||

| No | 207(72.6) | 127(73.4) | 334(72.9) | |

| Yes | 78(27.4) | 46(26.6) | 124(27.1) | |

| ECOG | 0.421 | |||

| 0-1 | 276(96.8) | 165(95.4) | 441(96.3) | |

| 2-3 | 9(3.2) | 8(4.6) | 17(3.7) | |

| Pathological type | 0.789 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 221(77.5) | 136(78.6) | 357(77.9) | |

| Other | 64(22.5) | 37(21.4) | 101(22.1) | |

| Histological grade | 0.692 | |||

| Low | 25(38.5) | 19(42.2) | 44(40.0) | |

| High | 40(61.5) | 26(57.8) | 66(60.0) | |

| Ki-67 index | 0.611 | |||

| < 25% | 91(46.0) | 49(43.0) | 140(44.9) | |

| ≥25% | 107(54.0) | 65(57.0) | 172(55.1) | |

| EGFR | 0.013 | |||

| Wild type | 84(43.5) | 70(57.9) | 154(49.0) | |

| Mutant type | 109(56.5) | 51(42.1) | 160(51.0) | |

| T stage | 0.522 | |||

| T1-T3 | 153(59.3) | 103(62.4) | 256(60.5) | |

| T4 | 105(40.7) | 62(37.6) | 167(39.5) | |

| N stage | 0.262 | |||

| N0 | 55(19.3) | 41(23.7) | 96(21.0) | |

| N1-N3 | 230(80.7) | 132(76.3) | 362(79.0) | |

| TNM stage | 0.733 | |||

| Ⅲ | 90(31.6) | 52(30.1) | 142(31.0) | |

| Ⅳ | 195(68.4) | 121(69.9) | 316(69.0) | |

| Treatment | 0.002 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 168(58.9) | 127(73.4) | 295(64.4) | |

| Targeted therapy | 117(41.1) | 46(26.6) | 163(35.6) | |

2.2 TGR与NSCLC的生存曲线

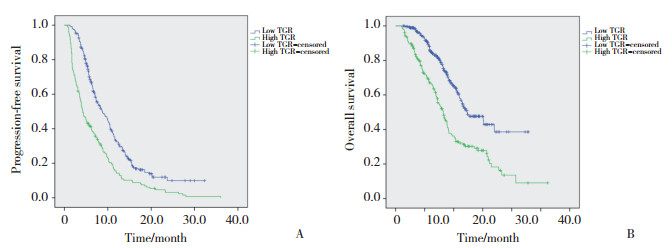

采用Kaplan-Meier法进行无进展生存期(progression-free survival, PFS)及总生存期(overall survival, OS)生存分析。整体中位PFS为7.1个月, 低TGR组中位PFS为8.7个月, 高TGR组中位PFS为4.2个月(P < 0.001);整体中位OS为21.3个月, 低TGR组中位OS为24.6个月, 高TGR组中位OS为16.4个月(P < 0.001);低TGR组的PFS及OS时间均明显优于高TGR组。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 TGR与NSCLC患者预后的关系 Fig.1 Relationship between TGR and the prognosis of NSCLC patients |

2.3 Cox回归分析TGR对NSCLC预后的影响

将各个临床病理参数和TGR纳入Cox回归模型进行单因素分析, 将P < 0.200的影响因素进行多因素分析。结果提示:有吸烟史(HR=3.463;95% CI:1.272, 9.428;P = 0.015)、组织学为低未分化(HR= 4.586;95% CI:1.795, 11.721;P = 0.001)、临床分期为Ⅳ期(HR=4.613;95% CI:1.870, 11.384;P = 0.001)、高TGR (HR=2.991;95% CI:1.330, 6.732;P = 0.002)为PFS的独立危险因素; 病理类型为非腺癌(HR=5.198; 95% CI:1.148, 23.524;P = 0.032)、高Ki-67指数(HR=5.057;95% CI:1.283, 19.932;P = 0.021)、临床分期为Ⅳ期(HR=9.932;95% CI:2.940, 33.549;P < 0.001)、高TGR (HR= 10.103;95% CI:3.044, 33.528;P < 0.001)为OS的独立危险因素。见表 2、3。

| Clinicopathological feature | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Gender (male vs female) | 1.761 | 1.429-2.169 | < 0.001 | 0.380 | 0.142-1.020 | 0.055 | |

| Age (≥60 vs<60 years) | 0.972 | 0.794-1.191 | 0.787 | ||||

| Smoking (yes vs no) | 1.574 | 1.285-1.929 | < 0.001 | 3.463 | 1.272-9.428 | 0.015 | |

| Family history (yes vs no) | 1.055 | 0.838-1.329 | 0.648 | ||||

| ECOG (2-3 vs 0-1) | 1.060 | 0.641-1.750 | 0.821 | ||||

| Pathology (other vs adenocarcinoma) | 1.949 | 1.530-2.484 | < 0.001 | 2.187 | 0.763-6.265 | 0.145 | |

| Histological grade (low vs high) | 1.707 | 1.113-2.618 | 0.014 | 4.586 | 1.795-11.721 | 0.001 | |

| Ki-67 index (≥25% vs<25%) | 1.717 | 1.340-2.201 | < 0.001 | 0.799 | 0.343-1.863 | 0.604 | |

| EGFR (wild vs mutant) | 2.121 | 1.648-2.731 | < 0.001 | 3.152 | 0.869-11.436 | 0.081 | |

| T stage (T4 vs T1- T3) | 0.964 | 0.778-1.195 | 0.738 | ||||

| N stage (N1-N3 vs N0) | 1.065 | 0.834-1.359 | 0.614 | ||||

| TNM stage (Ⅳ vs Ⅲ) | 0.725 | 0.582-0.902 | 0.004 | 4.613 | 1.870-11.384 | 0.001 | |

| Treatment (chemotherapy vs targeted therapy) | 2.623 | 2.082-3.304 | < 0.001 | 0.300 | 0.083-1.088 | 0.067 | |

| TGR (high vs low) | 1.934 | 1.575-2.375 | < 0.001 | 2.991 | 1.330-6.723 | 0.002 | |

| Clinicopathological feature | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Gender (male vs female) | 1.761 | 1.334-2.325 | < 0.001 | 1.192 | 0.290-4.902 | 0.808 | |

| Age (≥60 vs<60 years) | 1.285 | 0.974-1.694 | 0.076 | 2.514 | 0.636-9.930 | 0.188 | |

| Smoking (yes vs no) | 1.817 | 1.373-2.405 | < 0.001 | 1.979 | 0.404-9.690 | 0.400 | |

| Family history (yes vs no) | 1.114 | 0.821-1.512 | 0.487 | ||||

| ECOG (2-3 vs 0-1) | 1.857 | 1.035-3.333 | 0.038 | 0.473 | 0.028-7.946 | 0.603 | |

| Pathology (other vs adenocarcinoma) | 2.042 | 1.505-2.770 | < 0.001 | 5.198 | 1.148-23.524 | 0.032 | |

| Histological grade (low vs high) | 1.633 | 0.938-2.844 | 0.083 | 1.311 | 0.373-4.609 | 0.672 | |

| Ki-67 index (≥25% vs<25%) | 2.112 | 1.483-3.007 | < 0.001 | 5.057 | 1.283-19.932 | 0.021 | |

| EGFR (wild vs mutant) | 2.928 | 2.016-4.253 | < 0.001 | 5.241 | 0.520-52.848 | 0.160 | |

| T stage (T4 vs T1- T3) | 1.004 | 0.750-1.345 | 0.979 | ||||

| N stage (N1-N3 vs N0) | 1.292 | 0.916-1.822 | 0.144 | 1.781 | 0.408-7.770 | 0.443 | |

| TNM stage (Ⅳ vs Ⅲ) | 0.749 | 0.561-0.999 | 0.049 | 9.932 | 2.940-33.549 | < 0.001 | |

| Treatment (chemotherapy vs targeted therapy) | 2.171 | 1.570-3.003 | < 0.001 | 0.390 | 0.066-2.325 | 0.302 | |

| TGR (high vs low) | 2.239 | 1.696-2.957 | < 0.001 | 10.103 | 3.044-33.528 | < 0.001 | |

3 讨论

全球范围内肺癌的发病率及死亡率逐年升高。随着基因检测及靶向治疗时代的到来, 肺癌基因型的异同对其治疗选择及预后有着显著影响, 更加需要新的指标对肿瘤的动态变化进行评估。传统的影像学仅提供主观、半定量的信息, 辅助临床决策的判定有限, 通过更加精准的影像学信息发掘肿瘤生长、药物疗效及生存预后的信息, 将是研究的重点。

TGR在肾癌、乳腺癌、结直肠癌、肝癌、鼻咽部鳞癌等多种肿瘤中与PFS和OS显著相关[10-14], 尤其在肾癌领域, TGR已经进入临床决策层面, 直接影响治疗方案的选择及预后的评估[15]。本研究回顾性收集458例NSCLC患者的临床资料并计算TGR, 分析TGR与临床病理参数及预后的关系。结果表明, TGR与NSCLC患者预后相关, 高TGR患者生存期较短, 且为影响预后的独立危险因素。NISHINO等[16]的研究发现, 一线厄洛替尼或吉非替尼治疗的EGFR突变型晚期NSCLC患者的8周肿瘤体积减少与生存率有关, 从侧面验证了本研究方向的正确性。

本研究是一项在单中心进行的回顾性研究, 研究时间和样本数量有限。本研究排除了接受手术、放疗后出现复发转移的患者, 纳入的晚期人群不够全面; 排除了基线时仅包含不可测量病灶(如仅有胸腔积液或骨转移)、第1次疗效评价时出现新发病灶的患者, 因此未能评估这类具有侵袭性的肿瘤。最后, 考虑到肿瘤生长千变万化、人为测量的主观性及可变性, TGR的计算可能存在误差。

综上所述, 本研究表明TGR与NSCLC预后密切相关, 高TGR人群生存期短, 预后差。高TGR可作为影响NSCLC预后的独立危险因素。

| [1] |

SIEGEL RL, MILLER KD, JEMAL A. Cancer statistics, 2018[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(1): 7-30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21442 |

| [2] |

CHEN W, SUN K, ZHENG R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2014[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2018, 30(1): 1-12. DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.01.01 |

| [3] |

GOLDSTRAW P, CROWLEY J, CHANSKY K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project:proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2007, 2(8): 706-714. DOI:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a |

| [4] |

CRONIN KA, LAKE AJ, SCOTT S. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part Ⅰ:National cancer statistics[J]. Cancer, 2018, 124(13): 2785-2800. DOI:10.1002/cncr.31551 |

| [5] |

GOMEZ-ROCA C, KOSCIELNY S, RIBRAG V, et al. Tumour growth rates and RECIST criteria in early drug development[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2011, 47(17): 2512-2516. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.012 |

| [6] |

FERTE C, FERNANDEZ M, HOLLEBECQUE A, et al. Tumor growth rate is an early indicator of antitumor drug activity in phase Ⅰ clinical trials[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2014, 20(1): 246-252. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2098 |

| [7] |

MILELLA M. Optimizing clinical benefit with targeted treatment in mRCC:"tumor growth rate" as an alternative clinical endpoint[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2016, 102: 73-81. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.019 |

| [8] |

WANG Q, GAO J, WU X. Pseudoprogression and hyperprogression after checkpoint blockade[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2018, 58: 125-135. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.018 |

| [9] |

CHAMPIAT S, DERCLE L, AMMARI S, et al. Hyperprogressive disease is a new pattern of progression in cancer patients treated by anti-PD-1/PD-L1[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(8): 1920-1928. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1741 |

| [10] |

VAN BOCKEL LW, VERDUIJN GM, MONNINKHOF EM, et al. The importance of actual tumor growth rate on disease free survival and overall survival in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2014, 112(1): 119-124. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2014.06.004 |

| [11] |

SUZUKI C, BLOMQVIST L, SUNDIN A, et al. The initial change in tumor size predicts response and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with combination chemotherapy[J]. Ann Oncol, 2012, 23(4): 948-954. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdr350 |

| [12] |

YANG W, ZHAO J, HAN Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of facial nerve schwannomas with favorable facial nerve function:tumor growth rate is correlated with initial tumor size[J]. Am J Otolaryngol, 2015, 36(2): 163-165. DOI:10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.10.019 |

| [13] |

YOO TK, MIN JW, KIM MK, et al. In vivo tumor growth rate measured by US in preoperative period and long term disease outcome in breast cancer patients[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(12): e0144144. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0144144 |

| [14] |

LEE SH, KIM YS, HAN W, et al. Tumor growth rate of invasive breast cancers during wait times for surgery assessed by ultrasonography[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(37): e4874. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000004874 |

| [15] |

GRANDE E, MARTINEZ-SAEZ O, GAJATE-BORAU P, et al. Translating new data to the daily practice in second line treatment of renal cell carcinoma:the role of tumor growth rate[J]. World J Clin Oncol, 2017, 8(2): 100-105. DOI:10.5306/wjco.v8.i2.100 |

| [16] |

NISHINO M, DAHLBERG SE, FULTON LE, et al. Volumetric tumor response and progression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients treated with erlotinib or gefitinib[J]. Acad Radiol, 2016, 23(3): 329-336. DOI:10.1016/j.acra.2015.11.005 |

2019, Vol. 48

2019, Vol. 48