文章信息

- 王思亓, 李欣潞, 林庚, 王卓, 程晓凤, 刘彤彤, 郑玮

- WANG Siqi, LI Xinlu, LIN Geng, WANG Zhuo, CHENG Xiaofeng, LIU Tongtong, ZHENG Wei

- DMT1在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质中表达上调

- Elevation of Divalent Metal Transporter 1 Protein in the Cerebellar Cortex of the APP/PS1 Transgenic Mouse

- 中国医科大学学报, 2018, 47(3): 193-197

- Journal of China Medical University, 2018, 47(3): 193-197

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-09-28

- 网络出版时间:2018-03-02 17:38

2. 中国医科大学基础医学院组织学与胚胎学教研室, 沈阳 110122;

3. 锦州医科大学护理学院妇儿护理学教研室, 辽宁 锦州 121001;

4. 辽宁省人民医院神经内科, 沈阳 110016

2. Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Science, China Medical University, Shenyang 110122, China;

3. Department of Pediatric Nursing, College of Nursing, Jinzhou Medical University, Jinzhou 121001, China;

4. Department of Neurology, The People's Hospital of Liaoning Province, Shenyang 110016, China

阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer’s disease,AD)是一种起病隐匿的以进行性痴呆和情感障碍为主要临床症状的神经系统退行性疾病,常发生于老年及老年前期。AD的主要病理改变包括大量β -淀粉样蛋白(amyloid beta,Aβ)在细胞外沉积形成的老年斑,变性神经元内由Tau蛋白过度磷酸化形成的神经原纤维缠结,以及神经元缺失和脑淀粉样血管病变(cerebral amyloid angiopathy,CAA)。研究[1-2]证实,铁、铜和锌等金属离子与Aβ分泌、沉积和Tau蛋白磷酸化关系密切,因此以二价金属离子及其转运蛋白为切入点对AD发病机制进行研究是AD研究领域的热点之一。

二价金属离子转运体1(divalent metal transporter 1,DMT1)是维持细胞内二价金属离子稳态的重要转运蛋白,参与多种二价金属离子的转运。近年来,多项研究[3-6]证实在帕金森病患者和模型小鼠黑质内,DMT1表达增强,而自发突变导致的DMT1功能缺陷小鼠却能拮抗1-甲基-4-苯基-1,2,3,6-四氢吡啶和6-羟基多巴诱导的黑质神经元死亡等PD病理症状[4],最新的研究[7]证实DMT1过表达的转基因小鼠不仅在黑质区出现铁聚集,脑内Parkin蛋白的表达也显著升高。本课题组前期研究[8]则首次证实DMT1在AD患者尸检大脑皮层和APP/PS1转基因小鼠大脑皮层及海马老年斑内异常分布且表达升高。

小脑在运动型学习记忆中具有重要作用,小脑与大脑、脑干以及脊髓之间存在发达的传入、传出联系。研究[9-11]发现,晚期AD患者常出现小脑功能异常,浦肯野细胞核仁缩小[12]、树突减少[13],小胶质细胞增多[14],以及Aβ老年斑沉积[11, 15-16]。本研究组及其他科研团队的研究[17-18]发现,多种锌离子转运蛋白(zinc transporters,ZnTs)在AD前期患者及APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑中异常分布和表达,但目前尚无有关DMT1在AD小脑表达和变化的研究。因此,本研究拟通过免疫组织化学和免疫荧光双标染色及激光共聚焦扫描检测DMT1在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑内的定位和分布,应用Western blotting技术检测APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑内DMT1蛋白表达水平的变化,为进一步探讨二价金属离子及其转运体DMT1参与AD发病机理提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 实验动物9月龄APP/PS1转基因小鼠(购自美国Jackson Laboratory)与同月龄野生C57BL/6小鼠各7只,分笼饲养,常规饮食。

1.1.2 主要试剂DMT1兔多克隆抗体购自美国Alpha Diagnosis公司,Aβ小鼠单克隆抗体购自美国Sigma公司,GAPDH小鼠单克隆抗体购自美国Santa Cruz Biotechnology公司,FITC标记的驴抗兔抗体、Texas Red标记的驴抗小鼠抗体、正常驴血清均购自美国Jackson Immuno Research Laboratory公司,SABC免疫组织化学试剂盒购自中国博士德公司,ECL化学发光试剂盒购自美国Pierce公司。

1.2 实验方法 1.2.1 标本制备将APP/PS1转基因小鼠和C57BL/6野生型小鼠断头处死后,迅速取出小脑,一侧半球迅速放入4%多聚甲醛中固定,常规制备石蜡切片,用于免疫组织化学和免疫荧光化学染色;另一侧半球-80 ℃保存,用于Western blotting。

1.2.2 免疫组织化学和免疫荧光化学染色APP/PS1转基因小鼠和C57BL/6野生型小鼠的小脑组织石蜡切片常规二甲苯脱蜡、微波煮沸抗原修复后,用0.01 mol/L PBS充分冲洗。取用于Aβ免疫组织化学染色的标本,经5% BSA室温孵育1 h后,加入Aβ抗体(1︰400)4 ℃过夜,次日PBS充分漂洗后,加生物素—山羊抗小鼠IgG室温2 h,0.05 mol/L Tris-HCl充分漂洗,SABC室温1 h,DAB充分显色后,大量蒸馏水充分冲洗终止显色,苏木素复染,常规脱水、透明和封片,显微镜下观察并采集图像。取用于DMT1/Aβ免疫荧光双标染色的标本,经正常驴血清(1︰20)室温孵育1 h后,加入兔源DMT1抗体(1︰100)和小鼠源Aβ抗体(1︰400)混合液室温过夜,次日PBS充分漂洗后,加入FITC和Texas Red标记的荧光二抗混合液室温2 h,PBS充分漂洗后,甩干,荧光封片剂封片,共聚焦激光扫描显微镜下观察并采集图像。

免疫组织化学和免疫荧光染色的阴性对照:除使用正常血清代替一抗孵育小鼠小脑切片外,其他操作方法同上述免疫组织化学和免疫荧光染色,均未检测到明显的阳性反应产物。

1.2.3 Western blotting用PBS充分清洗APP/PS1转基因小鼠和C57BL/6野生型小鼠的小脑组织,分离皮层后称质量,按1︰5比例加入组织蛋白裂解液,超声粉碎,4 ℃裂解过夜。次日经超速低温离心(12 000 g,4 ℃)30 min后,小心抽取上清,考马斯亮蓝法测定组织蛋白量。10% SDS聚丙烯酰氨凝胶电泳分离蛋白样品后转膜至PVDF膜上,用含有5%脱脂奶粉和0.05% Tween 20的TBS(TTBS)封闭3 h,加入DMT1一抗(1︰2 000)和GAPDH一抗(1︰10 000)4 ℃孵育过夜。TTBS清洗PVDF膜3次,每次10 min,加入辣根过氧化物酶标记的二抗(1︰5 000)室温孵育2 h。TTBS清洗3次,每次10 min,滴加ECL发光液,用BIO-RAD凝胶电泳图像分析仪采图,Quantity One软件包进行数据分析。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 13.0统计软件进行统计学分析,应用Student t test方法进行数据分析,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

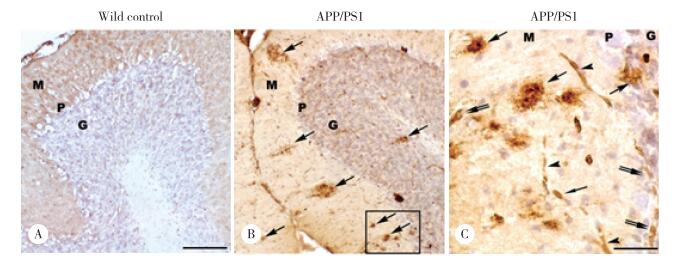

2 结果 2.1 小脑内Aβ阳性老年斑的分布光镜下,Aβ阳性免疫产物呈棕黄色,主要分布在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮层,呈大小不等的圆形、椭圆形或不规则形,中央有较致密的核心,边界较清晰(图 1B、1C),而野生型C57BL/6小鼠小脑皮质中未检测出Aβ阳性染色(图 1A)。在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮层中,高倍镜下可见Aβ阳性细胞分布于分子层和颗粒层中,还可见Aβ阳性毛细血管的分布(图 1C)。

|

| A, cerebellum of age-matched wild type control showing no significant Aβ positive immunostaining; B, Aβ positive plaques are predominately distributed in the molecular layer, but less in the granule cell layer of cerebellum (arrows); C, successive magnification of B, showing Aβ positive plaques (arrows), Aβ positive neuron (double arrows) and Aβ positive blood vessels (arrowheads). M, molecular layer; P, Purkinje cell layer; G, granule cell layer. Scale bars = 100 μm (A-B); 20 μm (C). 图 1 Aβ免疫阳性斑块在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质的分布 Fig.1 Distribution of amyloid beta immunoreactivity plaques in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse cerebellum |

2.2 DMT1和Aβ在老年斑中的定位分布

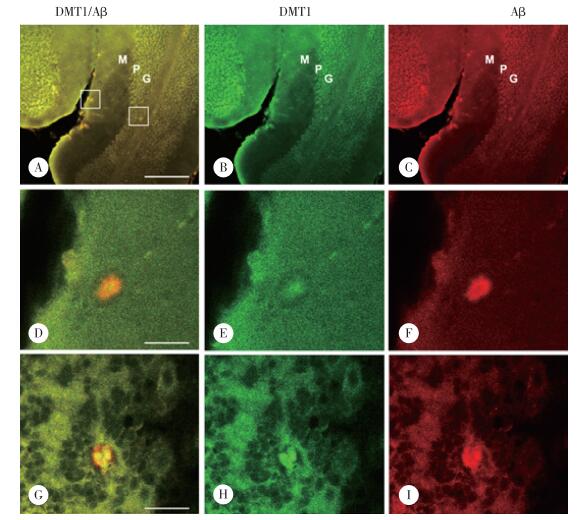

共聚焦激光扫描显微镜下,DMT1与Aβ免疫荧光双标结果显示,Aβ阳性的老年斑中均可见DMT1阳性染色,即DMT1和Aβ共定位于APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮层老年斑内(图 2)。高倍镜下显示斑块结构清楚,Aβ在分子层和颗粒层斑块内均呈弥散分布,但斑块中央部位的Aβ阳性反应较弱,周边部较强(图 2F、2I)。DMT1免疫阳性反应产物主要集中在斑块中央部位,周边较弱(图 2E、2H),与Aβ阳性分布存在共定位(图 2D、2G)。

|

| A-C, low magnification showing double immunofluorescence staining of DMT1 (B) in the Aβ positive plaques (C) in the cerebella cortex of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse; D-F, high magnification showing double immunofluorescence staining of DMT1 (E) and Aβ (F) in senile plaques in the molecular layer of the cerebellum of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse; G-I, high magnification showing double immunofluorescence staining of DMT1 (H) and Aβ (I) in senile plaques in the granule cell layer of the cerebellum of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse. M, molecular layer; P, Purkinje cell layer; G, granule cell layer. Scale bars = 100 μm (A-C); 20 μm (D-I). 图 2 DMT1在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质老年斑中的分布 Fig.2 Localization of divalent metal transporter 1 in senile plaques in the cerebellum of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse |

2.3 DMT1表达的Western blotting分析

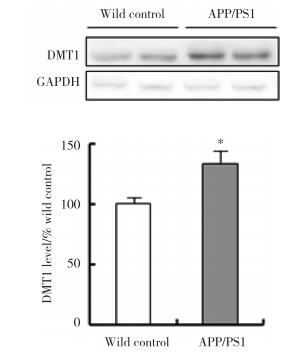

Western blotting结果显示,DMT1蛋白在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质内的表达水平明显高于野生型对照小鼠,表达量是野生型对照小鼠的173.4%(P < 0.01)(图 3)。

|

| *P < 0.01 vs wild control. 图 3 DMT1蛋白在APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质中的表达水平 Fig.3 Western blotting analysis to check DMT1 protein levels in the cerebellar cortex of APP/PS1 transgenic mice |

3 讨论

铜、铁、锌等二价金属离子在神经细胞的生理活动中具有重要作用,脑内这些金属离子的含量必须维持在特定范围内,如果稳态失衡就可能引发疾病。研究[1, 19-22]发现AD患者老年斑内部及周围均发现有铜、锌和铁富集;Tg2576小鼠脑内Aβ阳性斑块中也检测到了高于正常水平的铁和锌[23-24]。大脑皮层和海马是AD患者最容易受到病变损伤的脑区,在皮层和海马老年斑中检测到大量锌、铜和铁等金属离子与Aβ共同沉积,本研究组的前期研究[8]也证实了DMT1在AD患者大脑皮层以及APP/PS1小鼠脑内老年斑中有阳性表达,并与Aβ的分布相一致。小脑一直被认为受AD损伤的影响较小,然而,有研究[17]发现无症状临床前期的AD患者小脑皮质中可以检测到锌离子及锌转运蛋白(zinc transporters,ZNTs)ZnT4和ZnT6分布和表达异常,本研究组之前也发现APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑中存在锌离子、ZnT3和ZnT6的分布与表达异常[18]。因而,本研究对APP/PS1转基因小鼠小脑皮质中DMT1的表达和分布情况进行了检测,结果发现DMT1蛋白表达水平增高,且DMT1与Aβ在小脑老年斑中存在共定位。上述的证据表明二价金属离子及相关转运体,尤其是DMT1,可能参与了AD小脑中Aβ的沉积。

有研究[25-29]表明DMT1在脑内的分布主要集中于中脑、皮层和海马,有关小脑的分布的研究则较少。本研究中,Western blotting结果进一步证实APP/PS1小鼠小脑皮质中DMT1蛋白水平较野生型对照组小鼠明显增高,可能是由于DMT1蛋白在这些部位的老年斑中过度表达所致。CAA是AD的另一个重要的病理改变,有研究认为金属离子与CAA的形成密切相关,在本研究中同样发现DMT1在淀粉样变性的血管及其周围呈阳性染色。根据本研究的上述实验结果结合文献分析,笔者推测介导二价金属离子转运的DMT1与小脑Aβ老年斑的形成密切相关,DMT1表达上调可以增强细胞跨膜转运二价金属离子的能力,使血液中大量金属离子入脑并最终进入神经元,引起神经元内金属离子稳态失衡,进而通过氧化应激反应和Fenton反应等引起自由基增多,最终导致神经元变性、功能异常,甚至死亡。

DMT1在小脑皮质内异常分布和表达究竟是AD发生的某一始动因素,还是AD进展过程中的某种异常结局,现在还未可知,而且脑内参与金属离子跨细胞质膜转运的转运蛋白还有很多,它们之间存在着既协同又拮抗的作用,因而DMT1的异常分布和表达可能有着更复杂的含义,还需要更加细致和深入的研究。

| [1] |

WANG P, WANG ZY. Metal ions influx is a double edged sword for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Aging Res Rev, 2017, 35: 265-290. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2016.10.003 |

| [2] |

ROBERTS BR, RYAN TM, BUSH AI, et al. The role of metallobiology and amyloid-beta peptides in Alzheimer's disease[J]. J Neurochem, 2012, 120(Suppl 1): 149-166. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07500.x |

| [3] |

KE Y, CHANG YZ, DUAN XL, et al. Age-dependent and iron-independent expression of two mRNA isoforms of divalent metal transporter 1 in rat brain[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2005, 26(5): 739-748. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.002 |

| [4] |

SALAZAR J, MENA N, HUNOT S, et al. Divalent metal transporter 1(DMT1) contributes to neurodegeneration in animal models of Parkinson's disease[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(47): 18578-18583. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0804373105 |

| [5] |

ZHANG S, WANG J, SONG N, et al. Up-regulation of divalent metal transporter 1 is involved in 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP (+))-induced apoptosis in MES23.5 cells[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2009, 30(9): 1466-1476. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.025 |

| [6] |

HUANG E, ONG WY, GO ML, CONNOR JR. Upregulation of iron regulatory proteins and divalent metal transporter-1 isoforms in the rat hippocampus after kainate induced neuronal injury[J]. Exp Brain Res, 2006, 170(3): 376-386. DOI:10.1007/s00221-005-0220-x |

| [7] |

ZHANG CW, TAI YK, CHAI BH, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing the divalent metal transporter 1 exhibit iron accumulation and enhanced Parkin expression in the brain[J]. Neuromolecular Med, 2017, 19(2/3): 375-386. DOI:10.1007/s12017-017-8451-0 |

| [8] |

ZHENG W, XIN N, CHI ZH, et al. Divalent metal transporter 1 is involved in amyloid precursor protein processing and Abeta generation[J]. FASEB J, 2009, 23(12): 4207-4217. DOI:10.1096/fj.09-135749 |

| [9] |

KOBAYASHI K, FUKUTANI Y, HAYASHI M, et al. Non-familial olivopontocerebellar atrophy combined with late onset Alzheimer's disease:a clinico-pathological case report[J]. J Neurol Sci, 1998, 154(1): 106-112. DOI:10.1016/S0022-510X(97)00209-8 |

| [10] |

OLAJIDE OJ, UGBOSANMI AT, ENAIBE BU, et al. Cerebellar molecular and cellular characterization in rat models of Alzheimer's disease:neuroprotective mechanisms of garcinia biflavonoid complex[J]. Ann Neurosci, 2017, 24(1): 32-45. DOI:10.1159/000464421 |

| [11] |

CATAFAU AM, BULLICH S, SEIBYL JP, et al. Cerebellar amyloid-β plaques:how frequent are they, and do they influence 18F-florbetaben SUV ratios?[J]. J Nucl Med, 2016, 57(11): 1740-1745. DOI:10.2967/jnumed.115.171652 |

| [12] |

MANN DM, SINCLAIR KG. The quantitative assessment of lipofuscin pigment, cytoplasmic RNA and nucleolar volume in senile dementia[J]. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 1978, 4(2): 129-135. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1978.tb00553.x |

| [13] |

SJBECK M, ENGLUND E. Alzheimer's disease and the cerebellum:a morphologic study on neuronal and glial changes[J]. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2001, 12(3): 211-218. DOI:10.1159/000051260 |

| [14] |

MATTIACE LA, DAVIES P, YEN SH, et al. Microglia in cerebellar plaques in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Acta Neuropathol, 1990, 80(5): 493-498. DOI:10.1007/BF00294609 |

| [15] |

LEMERE CA, LOPERA F, KOSIK KS, et al. The E280A presenilin 1 Alzheimer mutation produces increased A beta 42 deposition and severe cerebellar pathology[J]. Nat Med, 1996, 2(10): 1146-1150. DOI:10.1038/nm1096-1146 |

| [16] |

WANG HY, D'ANDREA MR, NAGELE RG. Cerebellar diffuse amyloid plaques are derived from dendritic Abeta42 accumulations in Purkinje cells[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2002, 23(2): 213-223. DOI:10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00279-2 |

| [17] |

LYUBARTSEVA G, SMITH JL, MARKESBERY WR, et al. Alterations of zinc transporter proteins ZnT-1, ZnT-4 and ZnT-6 in preclinical Alzheimer's disease brain[J]. Brain Pathol, 2010, 20(2): 343-350. DOI:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00283.x |

| [18] |

ZHENG W, WANG T, YU D, et al. Elevation of zinc transporter ZnT3 protein in the cerebellar cortex of the AbetaPP/PS1 transgenic mouse[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2010, 20(1): 323-331. DOI:10.3233/JAD-2010-136 |

| [19] |

GONZLEZ-DOMNGUEZ R, GARCA-BARRERA T, GMEZ-ARIZA JL. Homeostasis of metals in the progression of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Biometals, 2014, 27(3): 539-549. DOI:10.1007/s10534-014-9728-5 |

| [20] |

DONG J, ATWOOD CS, ANDERSON VE, et al. Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid-beta within isolated senile plaque cores:Raman microscopic evidence[J]. Biochemistry, 2003, 42(10): 2768-2773. DOI:10.1021/bi0272151 |

| [21] |

SAYRE LM, PERRY G, HARRIS PL, et al. In situ oxidative catalysis by neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease:a central role for bound transition metals[J]. J Neurochem, 2000, 74(1): 270-279. DOI:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740270.x |

| [22] |

SUH SW, JENSEN KB, JENSEN MS, et al. Histochemically-reactive zinc in amyloid plaques, angiopathy, and degenerating neurons of Alzheimer's diseased brains[J]. Brain Res, 2000, 852(2): 274-278. DOI:10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02096-X |

| [23] |

LEE JY, MOOK-JUNG I, KOH JY. Histochemically reactive zinc in plaques of the Swedish mutant beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice[J]. J Neurosci, 1999, 19(11): RC10. |

| [24] |

CHEIGNON C, TOMAS M, BONNEFONT-ROUSSELOT D, et al. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Redox Biol, 2018, 14: 450-464. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.014 |

| [25] |

VEUTHEY T, WESSLING-RESNICK M. Pathophysiology of the Belgrade rat[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2014, 22(5): 82. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2014.00082 |

| [26] |

BURDO JR, SIMPSON IA, MENZIES S, et al. Regulation of the profile of iron-management proteins in brain microvasculature[J]. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2004, 24(1): 67-74. DOI:10.1097/01.WCB.0000095800.98378.03 |

| [27] |

BURDO JR, MENZIES SL, SIMPSON IA, et al. Distribution of divalent metal transporter 1 and metal transport protein 1 in the normal and Belgrade rat[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2001, 66(6): 1198-1207. DOI:10.1002/jnr.1256 |

| [28] |

GUNSHIN H, MACKENZIE B, BERGER UV, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter[J]. Nature, 1997, 388(6641): 482-488. DOI:10.1038/41343 |

| [29] |

KNUTSON M, MENZIES S, CONNOR J, et al. Developmental, regional, and cellular expression of SFT/UbcH5A and DMT1 mRNA in brain[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2004, 76(5): 633-641. DOI:10.1002/jnr.20113 |

2018, Vol. 47

2018, Vol. 47