文章信息

- 吴洋, 练继建, 闫玥, 齐浩.

- WU Yang, LIAN Ji-jian, YAN Yue, QI Hao.

- 巴氏芽孢八叠球菌及相关微生物的生物矿化的分子机理与应用

- Mechanism and Applications of Bio-mineralization Induced by Sporosarcina pasteurii and Related Microorganisms

- 中国生物工程杂志, 2017, 37(8): 96-103

- China Biotechnology, 2017, 37(8): 96-103

- http://dx.doi.org/DOI:10.13523/j.cb.20170814

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-05-02

- 修回日期: 2017-06-01

2. 系统生物工程教育部重点实验室 天津 300072;

3. 天津大学化工协同创新中心合成生物学平台 天津 300072;

4. 天津大学水利工程仿真与安全国家重点实验室 天津 300072;

5. 天津大学前沿技术研究院 天津 300072

2. Key Laboratory of Systems Bioengineering of Ministry of Education, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China;

3. SynBio Research Platform, Collaborative Innovation Center of Chemical Science and Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China;

4. State Key Laboratory of Hydraulic Engineering Simulation and Safety, Tianjin University, Tianjin 30072, China;

5. Frontier Technology Research Institute, Tianjin University, Tianjin 30072, China

生物矿化是从微生物到高等哺乳动物中广泛观测到的一种基于生化反应形成高分子材料的现象。其中,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌(Sporosarcina pasteurii,S. pasteurii)属于芽孢杆菌目球菌科芽孢八叠球菌属,革兰氏阳性菌,是一种尿素降解能力很高的,分离自土壤的细菌[1]。近年来,基于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌极高脲酶活性的碳酸钙生物矿化,在建筑[2]、环境[3]、乃至医疗[4]等领域得到了越来越广泛的应用,其中生物水泥、生物砖[5]等技术已经商业化,不仅成为了重要的工程技术,更是国内外学者的研究热点。

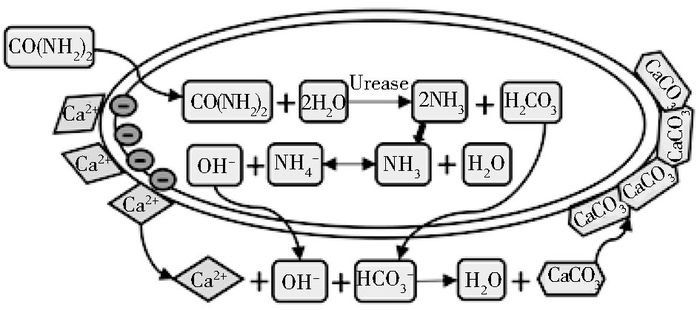

1926年,James B. Sumner通过结晶成功地证明了脲酶是一种蛋白质生物酶,并以此获得了1946年诺贝尔化学奖[6]。随后,基于脲酶的许多突破性科学成果接踵而至。脲酶属于酰胺基水解酶与磷酸二脂酶类超家族[7],是人类发现的第一个含有金属镍离子的酶[8]。其水解尿素的过程具体分为两步,首先尿素在脲酶的催化下水解为氨和氨基甲酸酯,随后氨基甲酸酯又能够自发降解为氨和碳酸根,最终生成两分子氨和一分子碳酸根[9]。巴氏芽孢八叠球菌凭借其极高的尿素降解活性,迅速提高细胞微环境的pH与碳酸根浓度。而该菌细胞壁带有负电,能吸附正电荷的钙离子[2]。钙离子遇到高浓度的碳酸根与氢氧根,就会以细胞为晶核形成碳酸钙沉降结晶,最终形成生物矿化物,如反应式(1)~(4) 与图 1。由此可见,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌在生物矿化中扮演着两个角色,一是促进碱性环境和碳酸根离子的形成;二是为矿化物沉降提供晶核[10]。

|

| 图 1 巴氏芽孢八叠球菌基于尿素代谢的生物矿化过程示意 Figure 1 Bio-mineralization process induced by urease in Sporosarcina pasteurii |

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

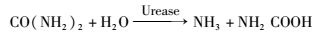

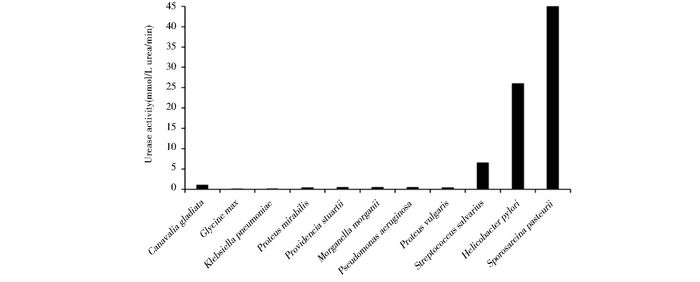

脲酶广泛存在于多种细菌、真菌、藻类、植物、动物[11]以及人体[12]中,承担着生物体固氮、改善酸性环境等功能。但只有在巴氏芽孢八叠球菌为代表的少数微生物细胞中观测到了极高的尿素降解活性,可发生生物矿化反应。Whiffin[13]通过对多物种的脲酶活性的对比研究,如图 2,发现相对于动植物的较低的脲酶活性,而微生物的脲酶活性总体较高,但菌种间差异也很大。变形杆菌(Proteus vulgaris)的脲酶活性在微生物中处于较低水平,与植物的脲酶基本一致[14]。幽门螺旋杆菌(Helicobacter pylori)的脲酶就有非常高的活性,可协助菌体在肠胃极酸环境中制造出中性的微环境[15]。而巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶活性几乎达到了已知物种的最大值,是刀豆脲酶活性的14倍,大豆脲酶活性的100倍[16],脲酶及相关基因的表达量可高达细胞干重的1%[17-18]。然而,对于如此高的尿素降解活性,单单以高脲酶表达量很难完全解释。此外,与巴氏芽孢八叠球菌在生物水泥等广泛的应用研究相比,对其生化分子机理的研究处于极其落后的状态,甚至连该菌的基因组序列都未有成功报道[19]。但凭借其脲酶活性,该菌已在建筑、环境、医疗等领域得到了广泛应用,本综述将从分子机理的角度,对迄今已了解的巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶相关机理研究进行介绍,并展望其应用前景。

|

| 图 2 碳酸钙生物矿化核心的尿素降解活性广泛保存于多种生物中 Figure 2 Urease activity of bio-mineralization widely distributed in species |

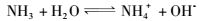

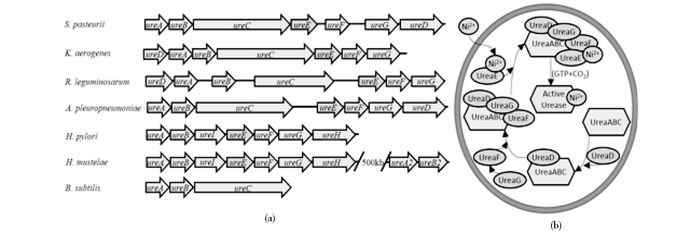

尽管不同物种的脲酶操纵子所包含的基因数量和顺序都不尽相同,但其核心基因的氨基酸序列尤其是活性中心的氨基酸是高度保守的,图 3a总结了部分物种的脲酶基因簇情况。除枯草芽孢杆菌外,大部分物种的脲酶基因簇都包含了ureA、ureB、ureC、ureD、ureE、ureF和ureG七个基因。在巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶基因簇中,ureA、ureB和ureC是脲酶的三个亚基基因,ureD、ureE、ureF和ureG是脲酶活性必需的辅助蛋白基因。研究证明ureD、ureF和ureG的特定基因突变,会极大地破坏细胞整体的脲酶活性[20];若删除部分ureE基因,细菌的脲酶活性将下降50%[21],可见辅助蛋白对脲酶至关重要,但其辅助酶活性的具体作用机理目前还未得到详细的研究。基于与模型菌的已知相关分子机理的对比,人们对于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶的分子机理有了初步的了解(图 3b)。首先,尿素降解的核心基因产物,组成UreABC的三亚基脲酶分子复合体,并会依次和辅助酶UreD、UreF和UreG结合,形成UreABC-UreDEF超级复合体,之后在镍离子结合蛋白UreE的作用下,将镍离子装入脲酶活性中心,形成有活性的脲酶[22-24],然而这一机理的很多部分还缺少详实的实验证实,其详细的分子间反应机理还需要进一步地研究验证。

|

| 图 3 尿素代谢相关分子机理 Figure 3 Molecular mechanism about urea metabolism (a) Comparison of urease gene cluster of different microorganisms (b) Interaction relationship of urease gene products in urea degradation |

脲酶基因的调控机制主要分为三类:第一类是铵根抑制型,这类微生物能够利用脲酶降解尿素产生铵根离子,再通过谷氨酰胺合成酶-谷氨酸合成酶通路以及谷氨酸脱氢酶的作用,直接利用铵根为自身的氮源。当环境的铵根浓度较高时,为了保证自身能量效率,就会抑制脲酶表达,如绿脓杆菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)、真养产碱杆菌(Alcaligenes eutrophus)、反刍兽杆菌(Bacillus megaterium)、克雷伯氏菌(Klebsiella aerogenes)等[25-26]。第二类是诱导表达型,当环境出现诱导条件时(如尿素、pH等)[27-28],细菌的脲酶表达量能提高5~25倍。这类微生物包括变性杆菌属(Proteus)、普罗威登菌属(Providencia)、沙门氏菌(Salmonella cubana)等。第三类是恒表达型,这类微生物的脲酶表达不受环境条件的抑制或诱导等作用调控,处于一个恒定的表达条件下,如摩氏摩根菌(Morganella morganii)等[25]。

巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶最初认为是恒表达型,即该菌的脲酶表达一直处于较高的表达水平,不受环境因素的影响[29-30]。但Whiffin等[13]发现,在巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的生长过程中,不同阶段的脲酶活性并不一致。该菌的脲酶活性在培养初期会快速上升,到对数期达到最大值,之后又随着时间缓慢下降,且脲酶的活性与菌量不成正比,这表明巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶表达是有一定的调控机制的,并非是恒表达型。当巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶活性下降时,将菌体收集并重新接种于新鲜培养基中,其脲酶活性会迅速回升。这说明培养过程中,脲酶活性的下降很可能与培养基中菌体代谢产物的积累有关。之后通过单因素实验研究发现,尿素减少、铵根和碳酸根的增加,对脲酶活性的影响都非常小[13]。在菌体的培养过程中,逐步提高培养基的pH值,其脲酶活性会随之下降;然而反过来,在培养过程中逐步降低培养基的pH值,其脲酶活性却没有太大变化[28]。这与之前将菌体接种至低pH的新培养基后,脲酶活性迅速回升的现象不太一致。这说明巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的脲酶基因表达调控不是由单一因素决定的,很可能是一个多因素的复杂调控机制,但其具体的机理还需要进一步详细研究。

1.2 高脲酶活性的生物学意义巴氏芽孢八叠球菌具有独特的ATP生成机制,该机制与脲酶水解尿素的过程紧密相关[31]。普通微生物在氧化能量物质后,产生的高能电子会通过电子传递链释放能量,并将质子转运至膜外,导致膜内外的质子浓度不一致,形成质子浓度梯度,构成质子动力势。此时,质子会顺着浓度梯度流回胞内,同时驱动膜上的质子泵ATP合成酶将ADP转化为ATP,实现质子驱动力向ATP的转化,为生命活动提供能量[32-33]。

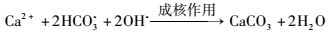

但巴氏芽孢八叠球菌为中度嗜碱菌,处在碱性环境中,质子在膜内浓度高,膜外浓度低,不能形成正确的质子动力势[34]。为解决这一问题,该菌形成了与铵根生产过程相偶联的ATP合成机制,如图 4所示。作为嗜碱菌,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的最适环境pH为9.25,胞内pH为8.4。当尿素由胞内脲酶水解产生铵根或氨分子后,铵根或氨分子会扩散到胞外。铵根和氨分子在溶液中处于平衡状态,当其在pH为9.25的胞外时,铵根与氨分子的比例是50:50;当其在pH为8.4的胞内时,铵根与氨分子的比例是30:70。所以铵根扩散到胞外后,会部分地转变为氨分子和质子,使得胞外的质子浓度高于胞内,形成质子动力势,驱动膜上的ATP合成酶合成ATP[31]。

|

| 图 4 巴氏芽孢八叠球菌尿素降解与细胞内关键高能化合物腺嘌呤核苷三磷酸和生物合成的关系 Figure 4 Relationship between urea degradation in Sporosarcina pasteurii and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) biosynthesis |

正因为巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的ATP合成机制与铵根、pH等紧密相关,所以菌体在无尿素或铵根的培养基中培养时,会因缺乏足量的ATP而无法生长[13]。而巴氏芽孢八叠球菌非常高的脲酶活性,也可能是为了满足菌体大量的ATP需求。在菌的培养过程中,脲酶活性呈现出先迅速上升,后缓慢下降的趋势。这也可以理解为生长初期需要快速降解尿素使环境pH值升至最适的9.25,并形成必要的质子动力势。随后下调脲酶活性,一是维持环境pH与质子动力势不需要太高的脲酶活性;二是为了避免环境过于碱性化,影响菌体生长。

2 巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的应用 2.1 建筑领域的应用巴氏芽孢八叠球菌诱导的碳酸钙沉积技术(Microbially Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation, MICP),一直是国内外研究者的研究热点。近年来,基于MICP的生物修复、生物水泥、生物砖等技术已经商业化并成为人们日常生活的一部分。

传统水泥建筑在使用一段时间后,总会出现一些微小的裂缝,影响建筑的寿命,并给建筑带来安全隐患。自修复水泥指的就是能够修复自身微小裂缝的水泥产品,目前主要有自然修复、化学自修复和生物自修复三种[35]。生物自修复水泥就是在水泥中添加能够进行生物矿化的微生物,如巴氏芽孢八叠球菌。这样的水泥出现裂缝后,一旦有水流过,就会激活菌体进行生物矿化反应,实现裂缝的修补[36]。但水泥中干燥、高碱性的环境并不适合微生物生存,而且微生物必须在水泥的恶劣环境中存活数年,直到裂缝出现再行使功能。巴氏芽孢八叠球菌是一种嗜碱菌,还能够产生休眠几十年的孢子,完全可以满足生物自修复水泥的要求[37]。但巴氏芽孢八叠球菌需要营养物质和钙离子才能进行矿化,若在水泥中添加糖类物质会使得水泥松软、易破损。于是Jonkers等[38]在生物水泥中加入了乳酸钙作为菌体营养和钙离子原料,最终制出了基于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的生物自修复水泥。这样的水泥具有较高的强度和耐受性[39]。2016年,美国有线电视新闻网(Cable News Network, CNN)报道了这一技术,并称其为“史上最受欢迎的建筑材料”。

用巴氏芽孢八叠球菌诱导碳酸钙沉降的方法,将沙粒粘连在一起形成的砖块,被称为生物砖[5]。与传统的高温砖窑方法相比,生物砖有很多优势:一方面,生物矿化不需要火,也就不需要耗费任何能源,既节约了能源,也减少了碳的排放;另一方面,通过对生物矿化的模具和固化硬化过程的控制,可以实现生物砖的外观、硬度和强度的定制,以满足一些特殊场合的使用需求[40]。Krieg等[41]在2012年创办了第一家生产生物砖的公司bioMASON。他们首先将沙土放入模具中,并向沙土接种巴氏芽孢八叠球菌溶液,每隔一段时间,浇灌一次生物矿化的盐溶液,以促进碳酸钙沉降和沙粒粘连,一段时间后就可得到生物砖。截至2016年,该公司已经生产了1.23万亿块生物砖,为全球减少了8亿吨二氧化碳的排放。

除了在生物水泥、生物砖等建筑材料方面的应用,基于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的MICP技术还可用于油田的裂缝封堵,控制原油流动,提高原油的开采率[42]。也有学者将此技术用于文物的表面保护,有效避免了文物的风化腐蚀和开裂破损[43]。

2.2 环境领域的应用在环境领域,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的高脲酶活性也广泛用于放射性元素和重金属污染的修复、沙漠化治理等。重金属污染对土壤和地下水的影响非常严重。传统的治理方法如化学反应、离子交换、膜分离等都非常昂贵而且低效[44]。巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的MICP技术作为一种新的治理方法,在重金属污染治理上发挥着重要的作用,可治理土壤中的镍、铜、铅、钴、锌、铬等重金属污染[45]。尤其是在高浓度重金属的污染区,其修复效率非常高,可清除97%到99.95%的重金属离子[44, 46]。该菌能如此高效地清除重金属离子,一方面是因为该菌高效地降解尿素后,能提供足量的阴离子(如碳酸根和氢氧根)与重金属离子结合沉降;另一方面,细菌的表面积比较大,有足够的位置与重金属沉降物结合反应[47]。在放射性元素修复方面,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌也曾用于锶污染的修复,并在24小时内,沉降出了95%的锶元素[48]。在优化碳源和修复方法后,其沉降效率还可以达到更高[49]。

在沙漠化治理方面,Harkes等[50]提出了利用MICP技术进行土壤加固,避免土壤沙化流失。之后,他的学生Magnus Larsson在TED(Technology Entertainment Design)演讲中讲述了他将沙丘变为建筑的设想。他设想用巴氏芽孢八叠球菌和沙漠自身的沙子,在撒哈拉大沙漠南北两侧,建造一个6000公里长的人工砂墙,阻挡大沙漠的扩散,保护非洲有限的耕地。同时,在人工砂墙的内部修建一些人工洞穴,这些洞穴冬暖夏凉,会非常适宜于人类居住,可供一些流浪者落脚[51]。Magnus Larsson凭借此设想获得了Holcim建筑设计大奖。

2.3 医疗领域的应用在医疗领域,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的高脲酶活性在肾功能衰竭的人群中有着广阔的应用前景。美国费城的Kibow生物技术公司,是一家专注于研发和商业化食用益生菌的企业,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌就是他们的产品之一。该菌具有较高的脲酶活性,可以帮助肾脏功能缺陷的人群降解体内尿素。而且巴氏芽孢八叠球菌不产毒素、不是病原菌,甚至曾在人类大便中发现过该菌的存在,因此该菌的临床使用对人体没有毒副作用。而食用巴氏芽孢八叠球菌比直接食用脲酶更有优势,因为菌体可以利用氨气作为其生长的氮源,与脲酶直接降解尿素相比,菌体释放的氨气更少,对人体的影响更小[4]。

在尿毒症小鼠的临床实验中发现,每天服用巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的小鼠,其血液中的尿素氮水平会显著下降,尿毒症的生存时间也会显著延长[52]。而慢性肾病患者在坚持服用该益生菌后,也出现了相似的结果,其血液的尿素氮水平明显下降[53-54]。这证明高脲酶活性的巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的确能帮助肾脏患者缓解症状,减轻病症。

3 结论与展望尿素降解对于微生物,乃至高等哺乳动物都是极为重要的生化代谢反应,基于脲酶活性,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌实现了极为高效的碳酸钙的生物矿化,并成为迄今为止观测到的基于尿素降解的碳酸钙生物矿化活性最高的微生物系统之一。并且由于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌分离自土壤,并未发现任何明显的对人的病原性,因此,巴氏芽孢八叠球菌及其相关菌在生物水泥及生物建筑方面的应用研究得到了长足发展,然而迄今人们的研究重点只止步于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的培养优化及其矿化形成的过程,对于巴氏芽孢八叠球菌生物矿化背后的分子机理的研究还相对落后。在全球最大的生物遗传信息数据库(GenBank)中,也只收录了巴氏芽孢八叠球菌为数有限的相关基因序列信息。巴氏芽孢八叠球菌高度的尿素降解活性被认为与ATP的代谢合成相关,然而至今还没有详实的实验数据可对其进行验证。巴氏芽孢八叠球菌的高脲酶与生物矿化活性,不能够单纯地以相关基因的高效表达来解释,可以推测巴氏芽孢八叠球菌必定具有一套完善的相关生物分子调控网络,包括脲酶相关基因的表达调控、相关底物及代谢产物的细胞内外的输入输出调控、以及对于高碱性的耐受等。对于这些分子机理的深入研究,并结合代谢工程及合成生物学等,必将更加有利地推动巴氏芽孢八叠球菌在建筑、环境乃至医疗领域的进一步应用。

| [1] |

Bhaduri S, Debnath N, Mitra S, et al. Microbiologically Induced Calcite Precipitation Mediated by Sporosarcina pasteurii. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2016, 2016(110): e53253-e53253. |

| [2] |

Rahman F, Afroz S, Efaz I H, et al. Application of microbiologically induced precipitation process in cement and concrete research:A review. Int. Conf. on Advances in Civil Infrastructure and Construction Materials, MIST, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015, 2015(1): 1-8. |

| [3] |

Zhu T, Dittrich M. Carbonate precipitation through microbial activities in natural environment, and their potential in biotechnology:A review. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2016, 4(4): 4. |

| [4] |

Macherone A, Ranganathan N, Patel B, et al. Bacillus pasteurii:A small microbe with huge potential. Journal of The American Society of Nephrology, 2002, 13(1): 766. |

| [5] |

Bernardi D, Dejong J T, Montoya B M, et al. Bio-bricks:Biologically cemented sandstone bricks. Construction and Building Materials, 2014, 55(2): 462-469. |

| [6] |

Karplus P A, Pearson M A, Hausinger R P. 70 years of crystalline urease:what have we learned?. Accounts of Chemical Research, 1997, 30(8): 330-337. DOI:10.1021/ar960022j |

| [7] |

Holm L, Sander C. An evolutionary treasure:unification of a broad set of amidohydrolases related to urease. Proteins:Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 1997, 28(1): 72-82. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0134 |

| [8] |

Benini S, Cianci M, Mazzei L, et al. Fluoride inhibition of Sporosarcina pasteurii urease:structure and thermodynamics. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry, 2014, 19(8): 1243-1261. DOI:10.1007/s00775-014-1182-x |

| [9] |

Anbu P, Kang C H, Shin Y J, et al. Formations of calcium carbonate minerals by bacteria and its multiple applications. Springerplus, 2016, 5(1): 250. DOI:10.1186/s40064-016-1869-2 |

| [10] |

Dhami N K, Reddy M S, Mukherjee A. Biomineralization of calcium carbonates and their engineered applications:a review. Front Microbiol, 2013, 4(314): 314. |

| [11] |

Dharmakeerthi R, Thenabadu M. Urease activity in soils:A review. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka, 2013, 24(3): 159-195. |

| [12] |

Yatsunenko T, Rey F E, Manary M J, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 2012, 486(7402): 222-227. |

| [13] |

Whiffin V S. Microbial CaCO3 precipitation for the production of biocement. Australia: Murdoch University, 2004.

|

| [14] |

Talaiekhozani A, Keyvanfar A, Andalib R, et al. Application of Proteus mirabilis and Proteus vulgarismixture to design self-healing concrete. Desalination and Water Treatment, 2013, 52(19-21): 3623-3630. |

| [15] |

Salama N R, Hartung M L, Muller A. Life in the human stomach:persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013, 11(6): 385-399. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro3016 |

| [16] |

Onal Okyay T, Frigi Rodrigues D. High throughput colorimetric assay for rapid urease activity quantification. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2013, 95(3): 324-326. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2013.09.018 |

| [17] |

Lauchnor E G, Topp D M, Parker A E, et al. Whole cell kinetics of ureolysis by Sporosarcina pasteurii. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2015, 118(6): 1321-1332. DOI:10.1111/jam.12804 |

| [18] |

Braissant O, Verrecchia E P, Aragno M. Is the contribution of bacteria to terrestrial carbon budget greatly underestimated?. Naturwissenschaften, 2002, 89(8): 366-370. DOI:10.1007/s00114-002-0340-0 |

| [19] |

Tiwari P K, Joshi K, Rehman R, et al. Draft genome sequence of urease-producing Sporosarcina pasteurii with potential application in biocement production. Genome Announcements, 2014, 2(1): 1-2. |

| [20] |

Liu X, Zhang Q, Zhou N, et al. Expression of an acid urease with urethanase activity in E. coli and analysis of urease gene. Molecular Biotechnology, 2017, 59(2-3): 84-97. DOI:10.1007/s12033-017-9994-x |

| [21] |

Mulrooney S B, Ward S K, Hausinger R P. Purification and properties of the Klebsiella aerogenes UreE metal-binding domain, a functional metallochaperone of urease. Journal of Bacteriology, 2005, 187(10): 3581-3585. DOI:10.1128/JB.187.10.3581-3585.2005 |

| [22] |

Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel R K. The Ubiquitous Roles of Cytochrome P450 Proteins:Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol.10. New Jersey:John Wiley & Sons, 2007. |

| [23] |

Colpas G J, Brayman T G, Ming L J, et al. Identification of metal-binding residues in the Klebsiella aerogenes urease nickel metallochaperone, UreE. Biochemistry, 1999, 38(13): 4078-4088. DOI:10.1021/bi982435t |

| [24] |

Musiani F, Zambelli B, Stola M, et al. Nickel trafficking:insights into the fold and function of UreE, a urease metallochaperone. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 2004, 98(5): 803-813. DOI:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.12.012 |

| [25] |

Kaltwasser H, Krämer J, Conger W. Control of urease formation in certain aerobic bacteria. Archiv für Mikrobiologie, 1972, 81(2): 178-196. DOI:10.1007/BF00412327 |

| [26] |

Carter E L, Boer J L, Farrugia M A, et al. The function of UreB in Klebsiella aerogenes urease. Biochemistry, 2011, 50(43): 9296. DOI:10.1021/bi2011064 |

| [27] |

Huang S C, Chen Y Y. Role of VicRKX and GlnR in pH-dependent regulation of the Streptococcus salivarius 57. I urease operon. mSphere, 2016, 1(3). |

| [28] |

Huang S C, Burne R A, Chen Y Y. The pH-dependent expression of the urease operon in Streptococcus salivarius is mediated by CodY. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(17): 5386-5393. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00755-14 |

| [29] |

Mörsdorf G, Kaltwasser H. Ammonium assimilation in Proteus vulgaris, Bacillus pasteurii, and Sporosarcina ureae. Archives of Microbiology, 1989, 152(2): 125-131. DOI:10.1007/BF00456089 |

| [30] |

Mobley H, Island M D, Hausinger R P. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiological Reviews, 1995, 59(3): 451-480. |

| [31] |

Al-Thawadi S M. Ureolytic bacteria and calcium carbonate formation as a mechanism of strength enhancement of sand. J Adv Sci Eng Res, 2011, 1(1): 98-114. |

| [32] |

Sazanov L A. A giant molecular proton pump:structure and mechanism of respiratory complex Ⅰ. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2015, 16(6): 375-388. DOI:10.1038/nrm3997 |

| [33] |

Casey J R, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2010, 11(1): 50-61. DOI:10.1038/nrm2820 |

| [34] |

Cuzman O A, Richter K, Wittig L, et al. Alternative nutrient sources for biotechnological use of Sporosarcina pasteurii. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 31(6): 897-906. DOI:10.1007/s11274-015-1844-z |

| [35] |

Talaiekhozan A, Keyvanfar A, Shafaghat A, et al. A review of self-healing concrete research development. Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques, 2014, 2(1): 1-11. |

| [36] |

Stabnikov V, Jian C, Ivanov V, et al. Halotolerant, alkaliphilic urease-producing bacteria from different climate zones and their application for biocementation of sand. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2013, 29(8): 1453-1460. DOI:10.1007/s11274-013-1309-1 |

| [37] |

Jonkers H M, Thijssen A, Muyzer G, et al. Application of bacteria as self-healing agent for the development of sustainable concrete. Ecological Engineering, 2010, 36(2): 230-235. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.12.036 |

| [38] |

Jonkers H. Self healing concrete:a biological approach. Self Healing Materials, 2008, 100(1): 195-204. |

| [39] |

Dhami N K, Reddy M S, Mukherjee A. Synergistic role of bacterial urease and carbonic anhydrase in carbonate mineralization. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2014, 172(5): 2552-2561. DOI:10.1007/s12010-013-0694-0 |

| [40] |

Mukherjee A, Dhami N K, Reddy B, et al. Bacterial calcification for enhancing performance of low embodied energy soil-cement bricks. Proceedings Third International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies, Kingston.2013.

|

| [41] |

Lokier S, Krieg Dosier G. A quantitative analysis of microbially-induced calcite precipitation employing artificial and naturally-occurring sediments. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, 2013, 15(1): 1-8. |

| [42] |

Dejong J T, Fritzges M B, Nüsslein K. Microbially induced cementation to control sand response to undrained shear. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 2006, 132(11): 1381-1392. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2006)132:11(1381) |

| [43] |

Marjadi D S. Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage:A biotechnological approach. Advances in Applied Science Research, 2016, 7(4): 159-167. |

| [44] |

Reddy M S. Biomineralization of calcium carbonates and their engineered applications:a review. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2013, 4(314): 314. |

| [45] |

Li M, Cheng X, Guo H. Heavy metal removal by biomineralization of urease producing bacteria isolated from soil. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 2013, 76(1): 81-85. |

| [46] |

Kang C H, Han S H, Shin Y, et al. Bioremediation of Cd by microbially induced calcite precipitation. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2014, 172(6): 2907-2915. DOI:10.1007/s12010-014-0737-1 |

| [47] |

Wong L S. Microbial cementation of ureolytic bacteria from the genus Bacillus:a review of the bacterial application on cement-based materials for cleaner production. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015, 93(1): 5-17. |

| [48] |

Warren L A, Maurice P A, Parmar N, et al. Microbially mediated calcium carbonate precipitation:implications for interpreting calcite precipitation and for solid-phase capture of inorganic contaminants. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2001, 18(1): 93-115. DOI:10.1080/01490450151079833 |

| [49] |

Lauchnor E G, Schultz L N, Bugni S, et al. Bacterially induced calcium carbonate precipitation and strontium coprecipitation in a porous media flow system. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(3): 1557-1564. |

| [50] |

Harkes M, Booster J, Van Paassen L, et al. Microbial induced carbonate precipitation as ground improvement method——bacterial fixation and empirical correlation CaCO3 vs strength. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Bio-Geo-Civil Engineering, 2008, 1(1): 23-25. |

| [51] |

Kraus C, Hirmas D, Roberts J. Microbially indurated rammed earth:a long awaited next phase of earthen architecture. ARCC Conference Repository, 2013, 2013(1): 58-65. |

| [52] |

Ranganathan N, Patel B G, Ranganathan P, et al. In vitro and in vivo assessment of intraintestinal bacteriotherapy in chronic kidney disease. Journal of theAmerican Society of Artificial Internal Organs, 2006, 52(1): 70-79. DOI:10.1097/01.mat.0000191345.45735.00 |

| [53] |

Mandal A, Das K, Roy S, et al. In vivo assessment of bacteriotherapy on acetaminophen-induced uremic rats. Journal of Nephrology, 2013, 26(1): 228-236. DOI:10.5301/jn.5000129 |

| [54] |

Ranganathan N, Friedman E A, Tam P, et al. Probiotic dietary supplementation in patients with stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease:a 6-month pilot scale trial in Canada. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 2009, 25(8): 1919-1930. DOI:10.1185/03007990903069249 |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37