扩展功能

文章信息

- 高涵, 王四宝

- GAO Han, WANG Si-bao

- 媒介肠道共生菌控制疟疾传播:20年进展与展望

- Malaria transmission block by vector Anopheles mosquito gut symbiotic bacteria: 20 years progress and prospect

- 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2021, 32(5): 509-512

- Chin J Vector Biol & Control, 2021, 32(5): 509-512

- 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2021.05.001

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2021-08-08

疟疾(malaria)是由疟原虫(Plasmodium)感染引起的真核寄生虫传染病。人感染疟疾后会出现发热(可能是周期性的)、头痛、寒战等症状,长期多次发作后可引起贫血和脾肿大,重症疟疾患者会出现多系统功能衰竭,甚至危及生命。感染人体的疟原虫有5种,即恶性疟原虫(P. falciparum)、间日疟原虫(P. vivax)、三日疟原虫(P. malariae)、卵形疟原虫(P. ovale)和诺氏疟原虫(P. knowlesi),其中恶性疟原虫和间日疟原虫对人类构成主要威胁[1]。2019年,全球约有2.29亿例疟疾病例,主要发生在撒哈拉以南的非洲。此外,东南亚、东地中海、西太平洋和美洲地区也报告了大量病例和死亡病例[1]。疟疾曾是我国发病人数最多的传染病。20世纪40年代,中国每年新发疟疾病例高达3 000万例。经长期努力我国已经消除本地感染,在疟疾防控上取得瞩目成就。2021年6月30日,世界卫生组织(WHO)宣布中国通过消除疟疾认证,见证了我国经过70年不懈努力到如今完全消除疟疾的伟大征程。

疟疾主要通过雌性按蚊(Anopheles spp.)叮咬传播给人类[2]。世界按蚊种类超过400种,大约有30种是重要的疟疾传播媒介[3]。人体疟原虫在人宿主和按蚊媒介中分别经历无性增殖和有性繁殖,具有复杂的生活史。媒介蚊虫控制是预防和减少疟疾传播的主要途径[4]。

在人类与疟疾的漫长斗争历程中,也取得了诸多人类医学史上里程碑式的重大研究发现和进步。与疟疾相关的研究成果曾五度获得诺贝尔奖,法国军医查尔斯·拉韦朗(1907年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖获得者)发现疟原虫是疟疾的真正元凶,英国医生罗纳德·罗斯(1902年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖获得者)证实按蚊是疟疾的传播媒介,瑞士昆虫学家保罗·米勒(1948年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖获得者)发现强效杀蚊剂滴滴涕(DDT),美国有机化学家罗伯特·伍德沃德(1965年诺贝尔化学奖获得者)人工合成了抗疟药物奎宁,我国科学家屠呦呦凭借抗疟药物青蒿素的研究成果荣获2015年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖,这些重大科学发现极大地促进了人们对疟疾的认知,有力推动了疟疾防治理念的变革和技术进步。

1 面临挑战人类与疟疾虽已经历了几个世纪的斗争,时至今日,这一古老的疾病仍然是最致命的寄生虫传染病之一,影响范围涉及近百个国家和地区。据WHO统计,全球近一半人口正面临疟疾风险,每年仍造成约50万人死于疟疾[5]。我国本土疟疾传播虽得到遏制,但输入性疟疾病例却维持高位,近年来我国每年输入性病例多达3 000例,对我国守住来之不易的抗疟成果构成严峻挑战[6-7]。随着国际经贸、文化交流以及国际交往日趋频繁,加之我国既往流行区传疟媒介依然存在,我国仍面临境外疟疾输入和输入后再传播的风险,我国疟疾的防控仍不能有丝毫松懈,巩固抗疟成果任重道远。尤为严峻的是,由于蚊虫抗药性和疟原虫耐药性的产生[5, 8-9],近年来全球在减少新增疟疾病例方面进展已趋放缓;同时全球疟疾死亡率下降速度也在放缓,2016-2018年的死亡率下降速度低于2010-2015年[5]。东南亚国家尤其是与我国毗邻的大湄公河区域国家多重耐药虫株的发现和扩散,对我国疟疾防控敲响了警钟[5, 10-12]。随着室内化学防治干预措施的长期使用,疟蚊的行为也日益发生变化。疟蚊的叮咬时间和室内叮咬比例均发生了显著变化,疟蚊不再在人们入睡时才去叮咬,而是趋向于户外叮咬人类。在撒哈拉沙漠以南非洲许多地区,因为无法使用常规工具对户外活动的疟蚊进行有效防控[13-14],户外蚊虫叮咬已成为当地疟疾流行的重要原因,并带来了新的挑战,为了应对疟疾防控面临的新挑战,亟需研发新的防控策略。

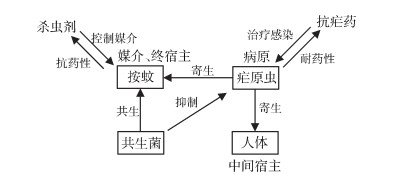

2 转变思路按蚊是疟疾传播的媒介昆虫,控制疟原虫在按蚊体内的感染,是源头阻断疟疾传播的新思路[15-16]。传统上人们通过杀虫剂来控制蚊虫的方式虽然在短期内能起到快速抑制蚊虫种群密度的效果,但从长期角度来看,不仅因农药残留对人类和生态环境造成危害,而且长期使用化学杀虫剂会使蚊虫产生抗药性[8-9]。此外,蚊虫是大自然食物链中的重要组成部分,彻底消灭蚊虫来根除疟疾既不现实也对生态无益。既然无法也难以消灭蚊虫,近年来科学家转变思路,期望通过降低甚至抑制蚊虫传播病原体的能力,来切断疟疾等蚊媒疾病的传播途径[15, 17](图 1)。

|

| 图 1 疟原虫与宿主互作关系及疟疾防控方法 Figure 1 Plasmodium parasites-hosts interactions and the strategy of blocking-up of malaria transmission |

| |

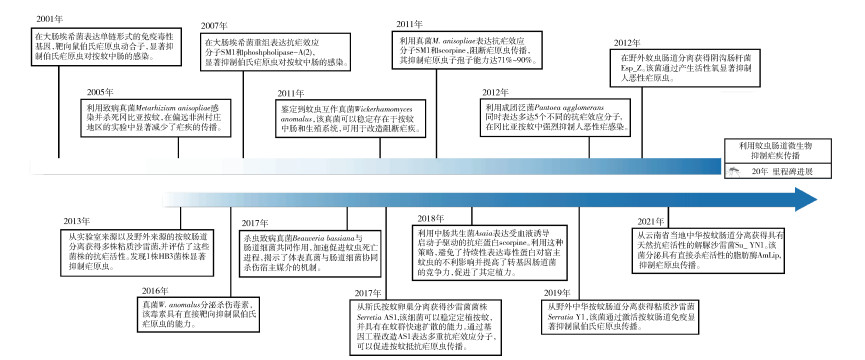

与人类肠道一样,按蚊中肠也定植着以革兰阴性细菌为主的肠道微生物[18-20]。当媒介按蚊叮咬带有疟原虫的人的血液时,疟原虫随血液一同进入按蚊中肠,绝大多数疟原虫在按蚊中肠肠腔内被抑制,因此按蚊中肠是疟原虫在蚊体内发育的最大屏障[21],是歼灭蚊虫体内疟原虫的绝佳战场[22-23]。同时,蚊虫吸血后,肠道共生细菌会成百上千倍地增殖[17, 24]。基于以上事实,科学家开启了利用按蚊肠道微生物来阻断疟疾传播的探索[15, 25],迄今已有20多年的历史(图 2)。最早的尝试始于2001年,利用大肠埃希菌(Escherichia coli)表达可以靶向疟原虫动合子的免疫毒性基因,以及具有杀疟活性的salivary gland and midgut peptide 1(SM1)等短肽,取得了一定的抑制效果[26],证明了这种思路的可行性。

|

| 图 2 利用疟蚊互作微生物阻断疟疾传播的研究进展情况 Figure 2 Advances in the use of the Anopheles mosquito microbiota to block malaria transmission |

| |

由于大肠埃希菌不是按蚊天然的肠道细菌,难以在按蚊肠道内定植,加上SM1抗疟小肽不是分泌表达,导致遗传改造的工程菌抑制疟原虫效果不理想。科学家开始运用蚊虫自身携带的微生物,例如体表寄生的真菌和肠道共生细菌,绿僵菌(Metarhizium)、白僵菌(Beauveria)、Asaia和泛菌属(Pantoea)等,利用虫生真菌直接防治蚊虫以期减少疟疾流行,或对真菌和细菌进行遗传改造使其分泌表达抗疟效应分子,取得了显著的抗疟效果[17, 27-34]。

传播疟疾的按蚊在世界各地有不同的蚊种,为了达到最佳的抗疟效果,需要找到在不同种按蚊肠道能够广泛存在并持续定植的核心共生菌。自2013年开始,我国科学家等开始聚焦于按蚊肠道核心共生菌—沙雷菌(Serratia spp.),直至找到了在不同蚊种中均具有优良定植能力的粘质沙雷菌(S. marcescens)菌株AS1[35]。AS1的一大优势是兼具水平和垂直传播,能够快速播散到整个蚊群中。为了避免或减少疟原虫对单一效应分子产生抗性,科学家构建了同时分泌表达多个抗疟效应分子的工程菌株,发挥“多弹头”攻击策略,可以高效抑制疟原虫在按蚊肠道内的发育,从而有效阻止蚊虫将疟原虫传染给人类[35]。然而,转基因细菌虽然能达到显著的抑制效果,但实际应用前面临的一个主要挑战是解决环境安全的担忧问题。如果能够发现天然抗疟活性的共生菌株,这个问题就会迎刃而解,并将极大地推动利用共生菌阻断疟疾传播新策略的应用实践[25, 36]。最近,我国科学家在云南省中华按蚊(An. sinensis)肠道分离到1株具有天然抗疟活性的新型解脲沙雷菌(S. ureilytica)菌株Su_YN1,并揭示了其通过分泌脂肪酶蛋白AmLip直接靶向杀灭疟原虫的抗疟分子机制;同时该共生菌株具有快速散播到蚊群的能力,为源头遏制疟疾传播提供绿色防控新武器[37]。

5 展望经过20多年的发展,利用肠道菌阻断疟疾传播的思路和技术不断进步,逐渐从实验室走向应用。然而要真正使该技术成熟并应用到疟疾防控中,还有较长的一段路要走,尤其是我们对按蚊肠道菌在中肠定植的机制知之甚少,对不同抗疟效应分子的表达和靶向疟原虫的机制研究尚待深入。按蚊肠道共生菌的宝库大门刚刚开启,深入挖掘蚊虫肠道菌资源,需要不断创新防控思路、迭代升级防控技术,助推共生菌防治策略走向实际应用。

利益冲突 无

| [1] |

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2019[R]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019: 4-15.

|

| [2] |

Talapko J, Škrlec I, Alebić T, et al. Malaria: the past and the present[J]. Microorganisms, 2019, 7(6): 179. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms7060179 |

| [3] |

Raghavendra K, Barik TK, Reddy BPN, et al. Malaria vector control: from past to future[J]. Parasitol Res, 2011, 108(4): 757-779. DOI:10.1007/s00436-010-2232-0 |

| [4] |

World Health Organization. Global vector control response 2017-2030[EB/OL]. (2017-10-02)[2021-08-04]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512978.

|

| [5] |

Hamilton WL, Amato R, van der Pluijm RW, et al. Evolution and expansion of multidrug-resistant malaria in southeast Asia: a genomic epidemiology study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2019, 19(9): 943-951. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30392-5 |

| [6] |

Zhou S, Li ZJ, Cotter C, et al. Trends of imported malaria in China 2010-2014:analysis of surveillance data[J]. Malaria J, 2016, 15(1): 39. DOI:10.1186/s12936-016-1093-0 |

| [7] |

咸越, 王曼丽, 邵天, 等. 我国疟疾防治政策演变及趋势分析[J]. 中国卫生政策研究, 2017, 10(3): 70-74. Xian Y, Wang ML, Shao T, et al. Analysis on the evolution and trend of malaria prevention and control policies in China[J]. Chin J Health Policy, 2017, 10(3): 70-74. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2017.03.012 |

| [8] |

Dondorp AM, Yeung S, White L, et al. Artemisinin resistance: current status and scenarios for containment[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2010, 8(4): 272-280. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2331 |

| [9] |

Ranson H, Lissenden N. Insecticide resistance in african Anopheles mosquitoes: a worsening situation that needs urgent action to maintain malaria control[J]. Trends Parasitol, 2016, 32(3): 187-196. DOI:10.1016/j.pt.2015.11.010 |

| [10] |

van der Pluijm RW, Imwong M, Chau NH, et al. Determinants of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: a prospective clinical, pharmacological, and genetic study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2019, 19(9): 952-961. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30391-3 |

| [11] |

Imwong M, Hien TT, Thuy-Nhien NT, et al. Spread of a single multidrug resistant malaria parasite lineage (PfPailin) to Vietnam[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2017, 17(10): 1022-1023. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30524-8 |

| [12] |

Haldar K, Bhattacharjee S, Safeukui I. Drug resistance in Plasmodium[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2018, 16(3): 156-170. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.161 |

| [13] |

Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015[J]. Nature, 2015, 526(7572): 207-211. DOI:10.1038/nature15535 |

| [14] |

Alonso PL, Tanner M. Public health challenges and prospects for malaria control and elimination[J]. Nat Med, 2013, 19(2): 150-155. DOI:10.1038/nm.3077 |

| [15] |

Wang SB, Jacobs-Lorena M. Genetic approaches to interfere with malaria transmission by vector mosquitoes[J]. Trends Biotechnol, 2013, 31(3): 185-193. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.01.001 |

| [16] |

崔春来, 陈晶晶, 王四宝. 蚊媒传染病的遗传控制和共生控制[J]. 应用昆虫学报, 2015, 52(5): 1061-1071. Cui CL, Chen JJ, Wang SB. Genetic control and paratransgenesis of mosquito-borne diseases[J]. Chin J Appl Entomol, 2015, 52(5): 1061-1071. DOI:10.7679/j.issn.2095?1353.2015.127 |

| [17] |

Wang SB, Ghosh AK, Bongio N, et al. Fighting malaria with engineered symbiotic bacteria from vector mosquitoes[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(31): 12734-12739. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1204158109 |

| [18] |

Strand MR. Composition and functional roles of the gut microbiota in mosquitoes[J]. Curr Opin Insect Sci, 2018, 28: 59-65. DOI:10.1016/j.cois.2018.05.008 |

| [19] |

Straif SC, Mbogo CNM, Toure AM, et al. Midgut bacteria in Anopheles gambiae and An. funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Kenya and Mali[J]. J Med Entomol, 1998, 35(3): 222-226. DOI:10.1093/jmedent/35.3.222 |

| [20] |

Wang Y, Gilbreath Ⅲ TM, Kukutla P, et al. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(9): e24767. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0024767 |

| [21] |

Whitten MMA, Shiao SH, Levashina EA. Mosquito midguts and malaria: cell biology, compartmentalization and immunology[J]. Parasite Immunol, 2006, 28(4): 121-130. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00804.x |

| [22] |

Abraham EG, Jacobs-Lorena M. Mosquito midgut barriers to malaria parasite development[J]. Insect Biochem Mol Biol, 2004, 34(7): 667-671. DOI:10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.019 |

| [23] |

Drexler AL, Vodovotz Y, Luckhart S. Plasmodium development in the mosquito: biology bottlenecks and opportunities for mathematical modeling[J]. Trends Parasitol, 2008, 24(8): 333-336. DOI:10.1016/j.pt.2008.05.005 |

| [24] |

Pumpuni CB, Demaio J, Kent M, et al. Bacterial population dynamics in three anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 1996, 54(2): 214-218. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.214 |

| [25] |

Gao H, Cui CL, Wang LL, et al. Mosquito microbiota and implications for disease control[J]. Trends Parasitol, 2020, 36(2): 98-111. DOI:10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.001 |

| [26] |

Riehle MA, Moreira CK, Lampe D, et al. Using bacteria to express and display anti-Plasmodium molecules in the mosquito midgut[J]. Int J Parasitol, 2007, 37(6): 595-603. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.12.002 |

| [27] |

Yoshida S, Ioka D, Matsuoka H, et al. Bacteria expressing single-chain immunotoxin inhibit malaria parasite development in mosquitoes[J]. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 2001, 113(1): 89-96. DOI:10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00387-X |

| [28] |

Fang WG, Vega-Rodríguez J, Ghosh AK, et al. Development of transgenic fungi that kill human malaria parasites in mosquitoes[J]. Science, 2011, 331(6020): 1074-1077. DOI:10.1126/science.1199115 |

| [29] |

Shane JL, Grogan CL, Cwalina C, et al. Blood meal-induced inhibition of vector-borne disease by transgenic microbiota[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9: 4127. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-06580-9 |

| [30] |

Cirimotich CM, Dong YM, Clayton AM, et al. Natural microbe-mediated refractoriness to Plasmodium infection in Anopheles gambiae[J]. Science, 2011, 332(6031): 855-858. DOI:10.1126/science.1201618 |

| [31] |

Cui CL, Wang Y, Liu JN, et al. A fungal pathogen deploys a small silencing RNA that attenuates mosquito immunity and facilitates infection[J]. Nat Commun, 2019, 10: 4298. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12323-1 |

| [32] |

Cappelli A, Valzano M, Cecarini V, et al. Killer yeasts exert anti-plasmodial activities against the malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei in the vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi and in mice[J]. Parasit Vectors, 2019, 12(1): 329. DOI:10.1186/s13071-019-3587-4 |

| [33] |

Ricci I, Damiani C, Scuppa P, et al. The yeast Wickerhamomyces anomalus(Pichia anomala) inhabits the midgut and reproductive system of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi[J]. Environ Microbiol, 2011, 13(4): 911-921. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02395.x |

| [34] |

Bando H, Okado K, Guelbeogo WM, et al. Intra-specific diversity of Serratia marcescens in Anopheles mosquito midgut defines Plasmodium transmission capacity[J]. Sci Rep, 2013, 3: 1641. DOI:10.1038/srep01641 |

| [35] |

Wang SB, Dos-Santos ALA, Huang W, et al. Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria[J]. Science, 2017, 357(6358): 1399-1402. DOI:10.1126/science.aan5478 |

| [36] |

Bai L, Wang LL, Vega-Rodríguez J, et al. A gut symbiotic bacterium Serratia marcescens renders mosquito resistance to Plasmodium infection through activation of mosquito immune responses[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 1580. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01580 |

| [37] |

Gao H, Bai L, Jiang YM, et al. A natural symbiotic bacterium drives mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium infection via secretion of an antimalarial lipase[J]. Nat Microbiol, 2021, 6(6): 806-817. DOI:10.1038/s41564-021-00899-8 |

2021, Vol. 32

2021, Vol. 32