扩展功能

文章信息

- 赵宁, Ishaq Sesay, 涂宏, Frederick Yamba, 任东升, 郭玉红, 鲁亮, 吴海霞, 刘小波, 岳玉娟, 李贵昌, 王君, 宋秀平, 王立立, 段招军, 刘起勇

- ZHAO Ning, ISHAQ Sesay, TU Hong, FREDERICK Yamba, REN Dong-sheng, GUO Yu-hong, LU Liang, WU Hai-xia, LIU Xiao-bo, YUE Yu-juan, LI Gui-chang, WANG Jun, SONG Xiu-ping, WANG Li-li, DUAN Zhao-jun, LIU Qi-yong

- 塞拉利昂弗里敦市2019年蚊媒监测结果分析

- An analysis of mosquito vector surveillance results in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2019

- 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2020, 31(3): 310-315

- Chin J Vector Biol & Control, 2020, 31(3): 310-315

- 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2020.03.013

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-04-09

2 塞拉利昂-中国友好生物安全实验室, 塞拉利昂 弗里敦 999127;

3 中国疾病预防控制中心寄生虫病预防控制所, 上海 200025;

4 塞拉利昂卫生部, 塞拉利昂 弗里敦 999127;

5 中国疾病预防控制中心全球公共卫生中心, 北京 102206;

6 中国疾病预防控制中心病毒病预防控制所, 北京 102206

2 Sierra Leone-China Friendship Biosafety Laboratory;

3 National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention;

4 Ministry of Health and Sanitation of Sierra Leone;

5 Global Public Health Center, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention;

6 National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention

塞拉利昂位于非洲西海岸, 是典型的热带气候, 温度范围为21~32 ℃, 平均温度为25 ℃;一年中主要有2个季节, 即雨季(5-10月)和旱季(11-4月), 7-8月有大量降雨, 年平均降雨量为320 cm, 相对湿度范围为60%~90%。塞拉利昂地形多样, 从海岸沼泽、内陆沼泽和热带雨林, 再到西非最高的山脉之一(Bintumani Mountain)。次生棕榈树是主要的植被, 并且散布着许多用于水稻种植的沼泽[1]。塞拉利昂适宜的温度、湿度和生态环境为蚊虫提供了理想的孳生场所, 蚊媒传播的有疟疾、淋巴丝虫病、黄热病、登革热、流行性乙型脑炎和寨卡病毒病等多种疾病[2]。全世界发现的3 000余种蚊虫中约有300种可以传播蚊媒病毒[3-4], 蚊媒疾病的发病率和死亡率非常高。2018年全球大约有2.28亿例疟疾病例, 非洲仍然是疟疾的高发地区, 共有2.13亿例(93.40%)疟疾病例[5]。塞拉利昂是非洲国家中疟疾发病率最高的国家之一[5], 疟疾已在塞拉利昂成为稳定且常年传播的蚊媒传染病, 约占50%的门诊病例, 且为5岁以下儿童发病和死亡的主要原因[6]。研究报道, 对塞拉利昂博城2012-2013年的发热病例进行血清学检测, 55%的病例至少感染了疟疾、登革热和基孔肯雅热中的一种, 塞拉利昂承受着非常重的蚊媒传播疾病负担[7-11]。尽管疟疾和其他蚊媒传播疾病负担如此沉重, 塞拉利昂的控制方法仍主要集中在病例管理, 而控制病媒、切断传播途径方面的努力非常有限。

病媒控制是预防、控制和消除蚊传疾病战略的重要组成部分。目前, 塞拉利昂预防和控制蚊媒传播疾病的主要措施为药浸蚊帐(insecticide treated nets, ITN)和室内滞留喷洒(indoor residual spraying, IRS), 这些措施的有效实施都必须建立在病媒监测能力的基础之上。但是, 塞拉利昂最近的昆虫学研究是在1990-1994年内战之前开展的[12], 缺乏近期蚊媒监测数据。因此, 迫切需要在塞拉利昂建立蚊媒监测能力, 以了解当地蚊虫密度、地域分布、种群特征和季节消长等情况, 为其制定蚊媒传播疾病的预防和控制措施提供科学依据。本研究在塞拉利昂首都弗里敦西部城区及农村设立了9个蚊媒监测点, 自2019年6-12月共监测蚊虫密度26次, 并对监测数据进行了统计分析。

1 材料与方法 1.1 数据来源塞拉利昂首都弗里敦市2019年6-12月的蚊媒监测数据来源于中国疾病预防控制中心援助塞拉利昂第5批专家组。塞拉利昂首都弗里敦市2019年4-12月降雨情况来自于中国气象局。

1.2 监测工具及监测点设置在塞拉利昂弗里敦市西部城区及农村共选取9个区域设置成蚊监测点, 分别选择居民区、一般单位、医院和牲畜棚各不少于1处。采用诱蚊灯(MYFS-HJY-1, 东莞厚积电子科技有限公司)法对成蚊进行监测。

1.3 监测方法及频率9个成蚊监测点, 每处布放2~4台诱蚊灯。布灯点选择室外避风避雨避光处, 诱蚊灯距离地面约1.5 m。于日落前1 h开始布放诱蚊灯, 翌日日出后1 h收集诱蚊灯的集蚊网, 带回实验室进行蚊类形态学鉴定。每周监测1次。

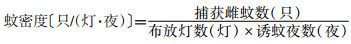

1.4 密度指标计算蚊虫密度指数计算公式:

|

采用ArcGIS 10.7软件绘制塞拉利昂弗里敦市蚊媒监测点地图。应用Excel 2007软件录入9个监测点的蚊媒监测数据, 计算监测成蚊总数、蚊种构成比、蚊虫密度季节变化消长等数据。

2 结果 2.1 蚊种构成及密度9个监测点分别设在Hill Station、Sorie Lane、Aberdeen、Congo Cross、New England、Waterloo、Lakka、Lumley和Locust社区内, 其中Lakka、Waterloo和Sorie Lane 3个监测点位于弗里敦市西部农村, 其他6个监测点位于弗里敦市西部城区, 监测点分布见图 1。

|

| 图 1 塞拉利昂弗里敦市蚊虫监测点分布 Figure 1 Distribution of mosquito surveillance sites in Freetown, Sierra Leone |

| |

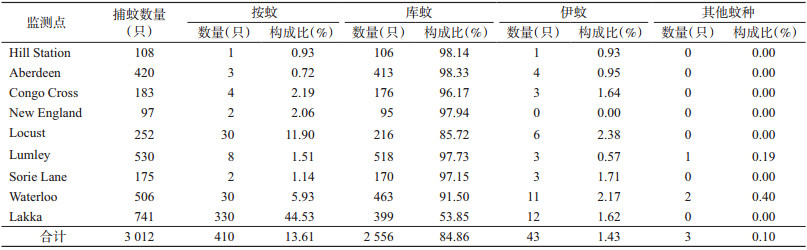

2019年6月26日至12月31日期间平均每周监测1晚, 共对9个监测点进行了26次蚊媒密度监测工作, 共收集蚊虫3 012只, 弗里敦地区平均蚊密度为4.35只/(灯·夜)。对捕获蚊虫进行属分类鉴定, 其中库蚊为2 556只, 占捕蚊总数的84.86%, 为优势蚊属;疟疾传播媒介按蚊占13.61%, 伊蚊占1.43%;各监测点蚊虫种类构成见表 1。

|

西部城区监测点结果显示, 库蚊在各监测点的构成比为85.72%~98.33%, 按蚊构成比为0.72%~11.90%;西部农村监测点结果显示, 库蚊在各监测点的构成比为53.85%~97.15%, 按蚊构成比为1.14%~44.53%, 见表 1。

2.2 不同监测点蚊密度平均蚊密度西部农村为5.01只/(灯·夜), 西部城区为3.87只/(灯·夜)。各个监测点进行比较, Lakka蚊密度最高, 为10.29只/(灯·夜);New England蚊密度最低, 为1.18只/(灯·夜);各监测点蚊密度见图 2。

|

| 图 2 塞拉利昂弗里敦市不同监测点平均蚊密度 Figure 2 Mean mosquito density at different surveillance sites in Freetown, Sierra Leone |

| |

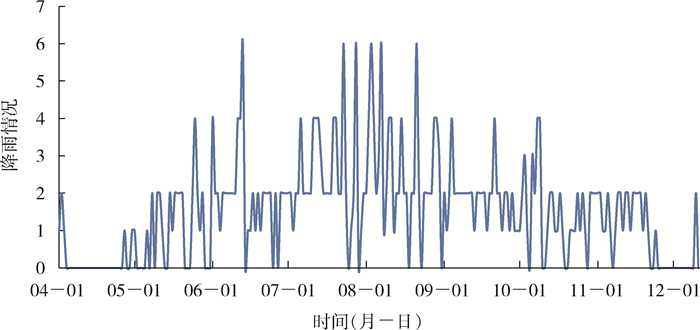

图 3、4显示, 自5月开始弗里敦地区出现小雨天气, 进入6月雨水进一步增多, 此时正是塞拉利昂旱、雨季交替时期, 6月底7月初的蚊虫密度处于较高水平, 最高达到6.42只/(灯·夜)。随着雨季的到来, 7和8月降雨量加大, 中雨和大雨天气明显增多, 蚊密度逐渐降低, 8月下旬到达谷底, 最低为1.60只/(灯·夜)。9月之后降雨量逐渐减少, 蚊密度回升, 10月底时蚊密度达到高峰, 为7.23只/(灯·夜)。11月降雨量进一步减少, 12月已基本无雨, 蚊密度有所回落, 最低为2.52只/(灯·夜)。

|

| 注:纵坐标中, 0.无雨;1.小雨~阴/多云;2.小雨;3.中雨~阴/多云;4.中雨;5.大雨~阴/多云;6.大雨。 图 3 2019年4-12月塞拉利昂弗里敦市降雨情况 Figure 3 Rainfall in Freetown, Sierra Leone, from April to December, 2019 |

| |

|

| 图 4 2019年6-12月塞拉利昂弗里敦市蚊虫季节消长 Figure 4 Seasonal variation of mosquito density in Freetown, Sierra Leone, from June to December, 2019 |

| |

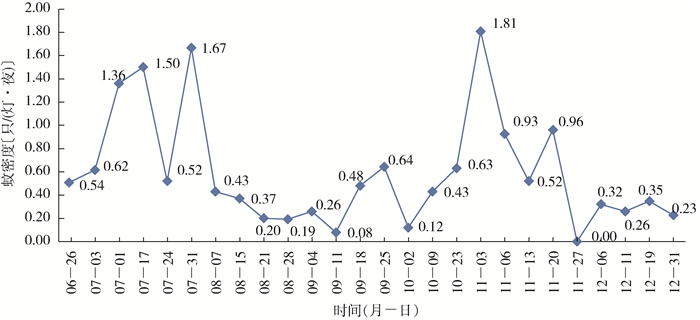

图 5显示, 按蚊密度季节消长趋势与总蚊密度趋势一致, 7月按蚊密度升高, 最高为1.67只/(灯·夜);8和9月按蚊密度较低, 最低为0.08只/(灯·夜);10月按蚊密度开始回升, 最高达1.81只/(灯·夜);12月随着旱季的到来, 按蚊密度开始降低。

|

| 图 5 2019年6-12月塞拉利昂弗里敦市按蚊季节消长 Figure 5 Seasonal variation of the mean density of Anopheles in Freetown, Sierra Leone, from June to December, 2019 |

| |

采集的410只按蚊, 其中362只来源于西部农村, 平均按蚊密度为1.28只/(灯·夜);48只采集于西部城区, 平均按蚊密度为0.12只/(灯·夜)。西部农村监测点Lakka占比最高为80.48%, 西部城区Hill Station监测点占比最低为0.24%(图 6)。

|

| 图 6 塞拉利昂弗里敦市不同监测点按蚊数量构成(%) Figure 6 Percentage of Anopheles at each surveillance site in Freetown, Sierra Leone |

| |

监测结果显示, 牲畜棚中蚊密度最高, 为10.40只/(灯·夜), 其次是居民区为4.45只/(灯·夜), 一般单位及医院的蚊密度较低, 分别为2.80和1.21只/(灯·夜)。进一步比较不同牲畜棚诱捕的蚊密度, Lakka、Lumley、Sorie Lane和Waterloo牲畜棚分别为17.45、11.68、6.27和5.44只/(灯·夜)。

3 讨论监测结果显示, 弗里敦地区库蚊占捕蚊总数的比例最高, 是优势蚊属, 其次是按蚊, 伊蚊数量最少, 但这并不能完全反映当地蚊虫的构成比, 因为伊蚊主要在白天活动, 而本研究中采用的诱蚊灯用于晚上监测, 所以伊蚊的数据不能代表当地的真实情况, 在后续的监测中可以同时考虑针对伊蚊的监测方法, 比如双层叠帐法和布雷图指数法等[13]。通过形态学鉴定, 弗里敦地区按蚊主要为冈比亚按蚊(Anopheles gambiae)和致死按蚊(An. funestus), 其中冈比亚按蚊为优势种, 该结果与1901年研究结果所述一致[1];伊蚊的优势种为埃及伊蚊(Aedes aegypti), 其他蚊种以及亚种需利用分子鉴定技术进行分类。西部农村及城区的监测结果显示, 西部农村诱捕到的平均总蚊密度和按蚊密度均大于西部城区, 而且按蚊在西部农村监测点的构成比高于西部城区, 尤其是Lakka监测点, 可能是因为Lakka周围有稻田, 稻田是按蚊喜爱的主要孳生地之一[2]。这些结果说明在西部农村, 特别是在按蚊喜欢的稻田和沼泽地等附近, 被蚊虫叮咬、感染疟疾的风险要高于西部城区。

塞拉利昂的雨季是每年的5-10月, 2019年从5月开始降雨量增加, 降雨量的增多是蚊密度增加的主要原因, 因此6月底7月初旱、雨季交替时期, 蚊密度处于较高水平。7和8月有大量降雨, 但是蚊密度却从7月底开始逐渐降低, 8月下旬达到谷底。蚊卵羽化出成蚊需要经历幼虫期和蛹期, 这个生长发育过程在稳定的水体内、适宜的温度条件下至少需要7 d [2], 而塞拉利昂的7、8月几乎每天都有大量的降雨, 过多的雨水不断冲刷着地面上的水体, 致使蚊卵还未完成生长发育过程, 就已经被新的雨水冲走, 故8月下旬的蚊密度反而很低。进入9月, 降雨量减少, 容易形成较稳定的水体供蚊虫孳生, 蚊密度开始反弹, 10月达到高峰。11月之后, 随着雨季的结束旱季的来临, 降雨量大量减少, 蚊虫的孳生地也会减少, 所以蚊密度有所回落。按蚊的密度季节消长趋势与总蚊密度趋势一致。上述结果也很好地解释了塞拉利昂疟疾传播的2个高峰, 第1个高峰在5月的雨季开始, 第2个高峰在10月底至11月期间[14]。上述结果提示, 塞拉利昂6-7月旱、雨季交替时期和10-11月雨、旱季交替时期为防控蚊媒及其传染病(如疟疾)的关键时期。

对不同生境的蚊密度进行比较, 发现蚊密度与各监测点环境卫生状况密切相关, 环境卫生状况较好的医院和一般单位, 蚊虫孳生地较少, 蚊密度较低, 其次是居民区, 牲畜棚的卫生环境最差, 蚊密度最高。进一步比较不同监测点牲畜棚之间的蚊密度, 发现Lakka的蚊密度要远高于其他牲畜棚监测点, 因为Lakka周围有稻田, 孳生地的存在与否在一定程度上决定了蚊密度的高低。塞拉利昂的《2016-2020年国家疟疾战略计划》包括3种主要媒介控制干预措施:睡觉时使用药浸蚊帐、室内残留喷洒和孳生地管理。该战略指出, 将根据塞拉利昂当前的风险情况分层次部署这些干预措施。尽管孳生地管理是塞拉利昂疟疾控制战略重要的一部分, 但目前并未实施[14]。因此, 建议塞拉利昂在今后预防和控制蚊媒传染病的措施中, 进一步加强蚊媒孳生地管理。

| [1] |

Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Sierra Leone malaria control strategic plan (2016-2020)[Z]. 2015: 23-41.

|

| [2] |

柳支英, 陆宝麟. 医学昆虫学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1990: 122-137. Liu ZY, Lu BL. Medical entomology[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1990: 122-137. |

| [3] |

Adams MJ, Lefkowitz EJ, King AMQ, et al. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2016)[J]. Arch Virol, 2016, 161(10): 2921-2949. DOI:10.1007/s00705-016-2977-6 |

| [4] |

俞永新. 虫媒病毒病的全球分布和重现概况[J]. 中华实验和临床病毒学杂志, 2005, 19(4): 401-407. Yu YX. Overview of the global distribution and recurrence of arbovirus diseases[J]. Chin J Exp Clin Virol, 2005, 19(4): 401-407. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9279.2005.04.029 |

| [5] |

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2019[R]. Geneva: WHO Press, 2019: 142-146.

|

| [6] |

Roth PJ, Grant DS, Ngegbai AS, et al. Factors associated with mortality in febrile patients in a government referral hospital in the Kenema district of Sierra Leone[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2015, 92(1): 172-177. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.14-0418 |

| [7] |

Dariano III DF, Taitt CR, Jacobsen KH, et al. Surveillance of vector-borne infections (chikungunya, dengue, and malaria) in Bo, Sierra Leone, 2012-2013[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2017, 97(4): 1151-1154. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0798 |

| [8] |

Ansumana R, Jacobsen KH, Leski TA, et al. Reemergence of chikungunya virus in Bo, Sierra Leone[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2013, 19(7): 1108-1110. DOI:10.3201/eid1907.121563 |

| [9] |

De Araújo Lobo JM, Mores CN, Bausch DG, et al. Short report:serological evidence of under-reported dengue circulation in Sierra Leone[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2016, 10(4): e0004613. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004613 |

| [10] |

Boisen ML, Schieffelin JS, Goba A, et al. Multiple circulating infections can mimic the early stages of viral hemorrhagic fevers and possible human exposure to filoviruses in Sierra Leone prior to the 2014 outbreak[J]. Viral Immunol, 2015, 28(1): 19-31. DOI:10.1089/vim.2014.0108 |

| [11] |

Schoepp RJ, Rossi CA, Khan SH, et al. Undiagnosed acute viral febrile illnesses, Sierra Leone[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2014, 20(7): 1176-1182. DOI:10.3201/eid2007.131265 |

| [12] |

Hay SI, Rogers DJ, Toomer JF, et al. Annual Plasmodium falciparum entomological inoculation rates (EIR) across Africa:literature survey, Internet access and review[J]. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2000, 94(2): 113-127. DOI:10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90246-3 |

| [13] |

中国疾病预防控制中心.全国病媒生物监测实施方案[Z].北京: 中国疾病预防控制中心, 2016: 16-28. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National vector surveillance implementation plan[Z]. Beijing: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016: 16-28. |

| [14] |

President's Malaria Initiative. Malaria operational plan FY 2018 & FY 2019, Sierra Leone[R]. Washington: PMI Press, 2017: 9-30.

|

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31