扩展功能

文章信息

- 侯祥, 刘可可, 刘小波, 常罡, 许磊, 刘起勇

- HOU Xiang, LIU Ke-ke, LIU Xiao-bo, CHANG Gang, XU Lei, LIU Qi-yong

- 气候因素对广东省登革热流行影响的非线性效应

- Nonlinear effects of climate factors on dengue epidemic in Guangdong province, China

- 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2019, 30(1): 25-30

- Chin J Vector Biol & Control, 2019, 30(1): 25-30

- 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2019.01.005

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-08-29

- 网络出版时间: 2018-12-6 20:18

2 中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所, 传染病预防控制国家重点实验室, 感染性疾病诊治协同创新中心, 世界卫生组织媒介生物监测与管理合作中心, 北京 102206

2 State Key Laboratory of Infections Disease Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, WHO Collaborating Centre for Vector Surveillance and Management

登革热是世界上传播迅速的蚊媒传染性疾病, 对经济、政治、社会和人类健康具有严重影响, 同时给全球带来极大的经济负担, 已成为严重的公共卫生问题[1]。2014年中国共感染登革热53 867例, 仅广东省就占39 707例。广东省感染的病例中, 本地病例占98.9%, 此次广东省登革热的发生是中国在过去30年间最严重的一次登革热暴发。中国最早报告发生登革热流行是在1873年厦门地区[2], 在1945年湖北省汉口地区出现登革热暴发[2], 之后的1949-1977年中国未再发生登革热暴发[3]。但是, 广东省佛山市在1978年出现登革热暴发, 这是由东南亚国家传播输入型病例引起的[3]。此后, 登革热疫情陆续在海南、广西、福建、浙江等省(自治区)暴发, 其中最严重的2次发生在1980和1986年的原广东省海南行政区(现海南省)。1991年以来登革热从海南省逐渐消失, 但在中国的南方仍然存在[4]。在中国, 登革热迅速蔓延, 并造成几次大的暴发, 但从1978年以来缺乏大尺度、宏观生态学方面的登革热定量模型分析的研究[5-6]。

登革热是一种气候敏感性的疾病, 其空间[7-8]和时间[8-9]分布动态均受到气候因素的影响, 如温度、降雨等[10-11]。气候因素通过潜在的改变媒介蚊虫密度和人类行为来促进登革热的传播, 从而导致接触登革热的人群数量增加, 尤其在温度适宜的地区更容易感染登革热和其他病媒传播疾病[12]。以往研究发现, 气候因素对登革热的影响可能是由于温度和降雨模式的变化[11, 13], 温度和降雨对登革热的暴发显现非线性效应[13-14]。有研究表明, 温度每增加1℃, 登革热患病数增加6%, 而降雨量每增加1 mm, 登革热患病数增加61%[15]。虽然在登革热流行风险与气候因素之间的关系方面有大量的研究, 但气候因素对登革热流行的复杂效应机制还不够清楚, 仍需要在中国等发展中国家进行大尺度范围的研究。本研究采取非线性统计模型方法, 通过分析广东省佛山、广州、汕头、深圳、珠海5个市2005-2015年气候因素、蚊媒种群密度对登革热传播的影响, 探讨气候因素与登革热暴发之间的关系, 其目的在于大尺度的研究广东省登革热流行的机制, 从而为登革热的控制和预防提供可靠依据。

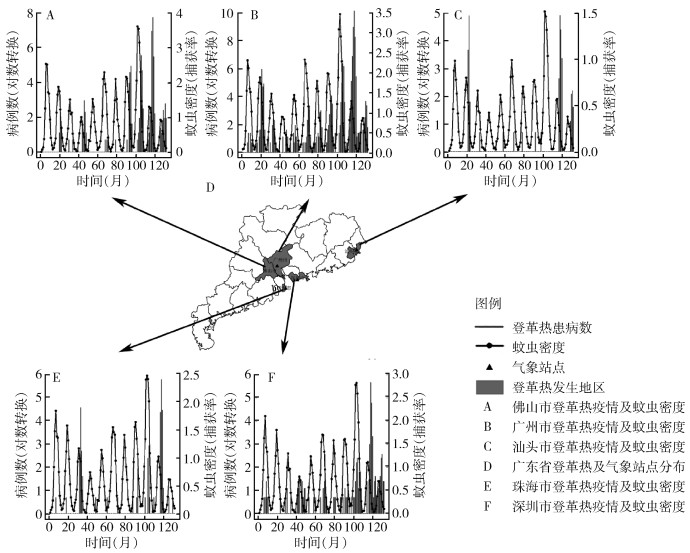

1 材料与方法 1.1 资料来源登革热监测数据来源于国家法定传染病监测系统, 覆盖了广东省佛山、广州、汕头、深圳、珠海5个市2005-2015年每月登革热病例数据(图 1A~F), 病例的确诊按照国家诊断标准(WS 216-2008)[4]。登革热个案病例类型分为当地病例(定义为登革热的发生由于当地传播而感染, 未离开过该地区或未到过有登革热疫情报道过的地区)和输入病例(定义为登革热的感染最可能发生在境内或者境外其他地区)。蚊虫密度信息主要来源于常规监测, 主要是成蚊监测(图 1A~F), 成蚊[白纹伊蚊(Aedes albopictus)]监测通过光捕捉器抽样调查, 蚊虫密度监测抽样地点包括居民区(每个月抽样数≥ 50户)、公园、建筑工地、医院等。月平均最高气温、月降雨天数数据均来自于国家气象信息中心(http://data.cma.cn/site/index.html)。采用距离各市最近的气象站数据进行匹配。

|

| 图 1 广东省2005-2015年登革热月份数据及分布 Figure 1 Monthly data and distribution of dengue fever from 2005 to 2015 in Guangdong province |

| |

通过数理统计模型, 研究生物因子间或生物因子与环境变量间的复杂非线性关系。建立以登革热病例数为相应变量的模型, 分别分析相应变量和蚊虫密度、当地气温、降雨的非线性关系。模型方程如下:

Di=a+b(Di-1)+c(Mosqutoi-1)+d(Tempi)+ f(Preci-1)×g(Locationi)+εi

模型中变量Di是i月监测点的登革热病例数; a为模型截距; b(Di-1)为监测点i-1月登革热病例数自回归变量(cubic regression spline function); c(Mosqutoi-1)为监测点i-1月蚊虫密度; d(Tempi)表示监测点i-1月平均最高气温; f(Preci-1)×g(Locationi)表示监测点i-1月降雨天数与广东省5个不同城市所在位置的交互作用; εi是随机误差项。

1.3 统计学方法采用广义可加模型(generalized additive models, GAM)作为数理统计分析方法[16], 连接函数为拟泊松分布函数。使用R软件(版本3.3.3), "mgcv"软件包(版本1.8-12)[16], 通过交互验证的方法筛选最优模型, 并且以广义交互验证指数(generalized cross validation, GCV)作为筛选参数[16-17], GCV值越低, 模型越优。

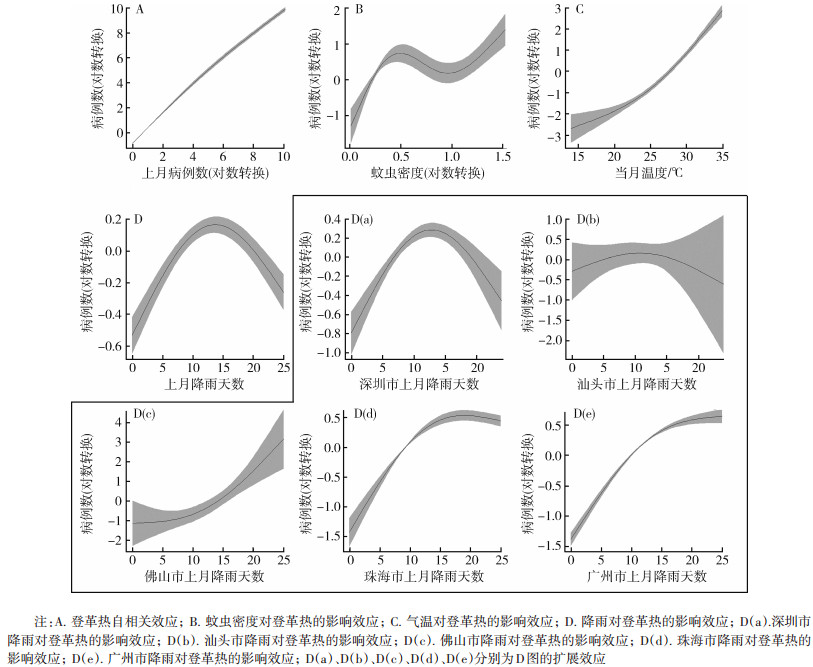

2 结果GAM分析生态环境因子对登革热的影响结果表明, 广东省登革热的流行存在显著的正向自我调节效应(F1.96, 10.84=6 588.650, P < 0.01;图 2A)。在生态因子方面, 蚊虫密度对登革热存在显著的非线性正效应(F2.98, 10.84=21.810, P < 0.01;图 2B)。此外, 在气象因素方面, 当月平均最高气温(F1.91, 10.84=215.570, P < 0.01;图 2C)显著影响登革热的发生, 表现为非线性正效应; 5个地区上月降雨天数对登革热的发生差异有统计学意义(F2.99, 10.84=101.590, P < 0.01;图 2D), 总体而言, 表现为"n"型非线性效应, 而图 2D(a)、(b)、(c)、(d)、(e)分别为图 2D的扩展效应。

|

| 图 2 广义可加模型对广东省登革热流行的分析结果 Figure 2 Analysis of dengue epidemic in Guangdong province by a generalized additive model |

| |

基于广东省5个市2005-2015年10年的登革热及蚊虫密度的监测数据, 采用GAM, 分析广东省10年间登革热暴发地区内生物因子、环境因子与登革热病例之间的复杂关系。研究结果表明, 登革热的流行与上月病例间存在非线性正相关, 与蚊虫密度间同样存在显著的非线性正相关, 与当月最高温度间存在非线性正相关, 并且上月降雨天数对不同地区登革热发生也存在非线性的"n"型效应。因此, 温度和降雨对登革热的流行有调节作用, 它们主要通过改变蚊虫种群密度, 影响种群变化, 从而影响登革热的流行和暴发。

登革热的流行存在显著的正向自我调节效应, 受上月病例的影响, 它们之间存在非线性的正相关, 上月病例数会影响本月登革热发生的概率及发生的病例数。大量研究表明[18], 在中国已经发生的登革热暴发病例中, 主要是通过国外(如东南亚[4]、印度[19])的输入病例所导致, 因此, 为更好地防治登革热的暴发, 应加强出入境检验检疫方面的工作。有研究发现[20], 我国台湾地区登革热暴发中, 输入病例在该暴发中起到关键作用, 对登革热在本地传播起到启动子的作用, 通过统计学发现, 登革热本地病例的发生与滞后2~14周的输入病例具有相关性。目前广东省登革热的流行形式主要是通过输入病例作为启动因子, 导致本地登革热低水平流行, 然后出现本地病例并快速传播, 达到一定数量, 当应对措施不当时, 将出现暴发[21]。因此, 登革热作为一种蚊媒传播的传染性疾病, 上月病例数对本月病例将具有较大的影响。

登革热作为一种重要的蚊媒传染病, 传播主要受蚊虫种群密度等影响, 一般会随蚊虫密度的增加而暴发流行。通过蚊虫携带病毒在人与人之间传播, 此过程中需要传染源、传播途径和易感人群[22], 而环境和社会因素在该过程中也会产生影响[21]。伊蚊是登革热传播的基础条件, 登革热的流行暴发主要受到伊蚊密度的影响。本研究结果表明, 蚊虫密度与登革热流行显现为非线性正相关, 蚊虫密度的增加会导致登革热的流行暴发, 与之前研究一致[11]。广东省在登革热暴发后, 通过实施灭蚊、环境卫生清理等活动, 导致蚊虫密度显著降低, 从而有效地控制疫情[23], 进一步说明蚊虫密度对登革热的流行暴发起着关键性的作用。有研究证明[24], 登革热的暴发一般发生在蚊虫密度高、人群密集及卫生条件差的地区, 并且暴发地区的蚊虫密度、人群数量与登革热的暴发具有相关性。在中国, 登革热主要是一种输入性疾病, 由于人群对登革热自然免疫力低, 随着蚊虫密度的增加, 使登革热病毒的传播更加容易, 从而导致登革热的流行暴发风险增加。

登革热的流行与当月最高温度显现为非线性正相关。总体而言, 登革热的流行随温度升高而升高, 这一结论与之前研究相一致[13]。温度会影响蚊虫叮咬率[25]、病毒的潜伏期[26]以及蚊虫-人接触率(如影响人们的户外时间或开窗户时间)等。在一定范围内, 温度升高, 会降低蚊虫的发育时间[27], 导致短时间内蚊虫密度升高。当温度较高时, 能缩短蚊虫发育时间(非成虫阶段), 产生大量形体小的蚊虫[28], 形体小的蚊虫吸血频率高于形体大的蚊虫[29], 由于蚊虫重复吸血可以增加病毒传播效力, 从而提高登革热的流行暴发。研究发现, 在18~31℃范围内, 随着温度增加, 会缩短登革热病毒在蚊虫体内的外潜伏期, 将产生大量具有传播能力的蚊虫, 当温度 < 18℃时, 蚊虫可能不会传播登革热病毒[26], 也不会导致登革热的流行暴发。有研究发现, 当温度处于高温时即>40℃, 温度导致蚊虫吸血频率的增加及病毒在蚊虫体内繁殖力的效应与蚊虫寿命的缩短将会抵消[30], 说明高温可促进登革热的流行暴发。但是, 当温度处于30~40℃时, 温度对蚊虫种群密度产生微弱的影响, 可能由于蚊虫会选择温度更低或者阴凉的栖息环境从而躲避高温所带来的危害[31]。有学者研究发现, 温度与登革热流行暴发密切相关, 月平均温度每升高1℃, 登革热的传播风险提高到原来的1.95倍[32], 从而引起登革热的流行。因此, 进一步说明温度主要通过影响蚊虫密度从而影响登革热的暴发。本研究中, 当温度升高时, 登革热的流行与温度显现为正相关, 即随着温度升高而升高, 这一结果与之前大量研究相一致。

不同地区登革热的流行与上月降雨天数显现为非线性的"n"型效应, 即当降雨天数 < 15 d时, 两者之间显现为正相关, 登革热的发生随着降雨天数增加而升高, 反之显现为负相关。大量研究发现, 登革热传播与降雨呈正相关关系[13]。降雨对蚊虫种群密度、成活率、繁殖率以及生长速度均有重要影响[33-34]。白纹伊蚊可在室内、外适合栖息的地方孳生, 当降雨量增加时, 可产生、增加蚊虫孳生地和栖息地, 也可提高蚊虫的孵化率, 增加幼虫数量, 达到蚊虫种群密度增加的效果, 从而导致登革热更加容易流行暴发[35]。降雨也可间接增加蚊虫吸血频率, 阴雨天时人群一般会在室内, 间接增加了人群与蚊虫的接触概率。另一方面, 当降雨量过高时, 不会促进登革热的流行暴发, 由于伊蚊的孳生地和栖息地会受到过高雨量的破坏, 不利于蚊虫种群发展[36]。因此, 本研究结果也说明当降雨量达到一定程度时, 登革热流行会随着降雨量的增加而降低。

广东省登革热暴发与上月病例、蚊虫密度、温度、降雨天数有显著关系, 当登革热上月病例数以及蚊虫密度超过安全阈值, 同时当地的温度和降雨条件适宜, 本地登革热的发生将成为可能。因此, 为了更好地控制和预防登革热的暴发, 应加强居民在卫生、健康教育方面的意识, 减少蚊虫孳生地和栖息地; 采用灭蚊措施, 降低蚊虫密度尤其是成蚊密度; 在雨季和气温较高时应做好防蚊、灭蚊工作, 提前应对登革热疫情, 减少流行和暴发的风险。

| [1] |

Kyle JL, Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue[J]. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2008, 62(1): 71-92. DOI:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163005 |

| [2] |

梁文佳, 何剑峰. 登革热的预防与控制[J]. 华南预防医学, 2005, 31(2): 76-79. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-5039.2005.02.031 |

| [3] |

Luo L, Liang HY, Hu YS, et al. Epidemiological, virological, and entomological characteristics of dengue from 1978 to 2009 in Guangzhou, China[J]. J Vector Ecol, 2012, 37(1): 230-240. DOI:10.1111/j.1948-7134.2012.00221.x |

| [4] |

Sang SW, Yin WW, Bi P, et al. Predicting local dengue transmission in Guangzhou, China, through the influence of imported cases, mosquito density and climate variability[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(7): e102755. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0102755 |

| [5] |

Zhang H, Zhang YR, Hamoudi R, et al. Spatiotemporal characterizations of dengue virus in mainland China:insights into the whole genome from 1978 to 2011[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(2): e87630. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0087630 |

| [6] |

Li B, Morton LC, Liu QY. Climate change and mosquito-borne diseases in China:a review[J]. Global Health, 2013, 9: 10. DOI:10.1186/1744-8603-9-10 |

| [7] |

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue[J]. Nature, 2013, 496(7446): 504-507. DOI:10.1038/nature12060 |

| [8] |

Che-Him N, Ghazali KM, Saifullah Rusiman M, et al. Spatio-temporal modelling of dengue fever incidence in Malaysia[J]. J Phys, 2018, 995(1): 012003. DOI:10.1088/1742-6596/995/1/012003 |

| [9] |

Xu HY, Fu X, Lee LK, et al. Statistical modeling reveals the effect of absolute humidity on dengue in Singapore[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2014, 8(5): e2805. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002805 |

| [10] |

Huber JH, Childs ML, Caldwell JM, et al. Seasonal temperature variation influences climate suitability for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika transmission[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2018, 12(5): e0006451. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006451 |

| [11] |

Betanzos-Reyes R, Rodríguez MH, Romero-Martínez M, et al. Association of dengue fever with Aedes spp. abundance and climatological effects[J]. Salud Publica Mex, 2018, 60(1): 12-20. DOI:10.21149/8141 |

| [12] |

Sutherst RW. Global change and human vulnerability to vector-borne diseases[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2004, 17(1): 136-173. DOI:10.1128/CMR.17.1.136-173.2004 |

| [13] |

Xu L, Stige LC, Chan KS, et al. Climate variation drives dengue dynamics[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2017, 114(1): 113-118. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1618558114 |

| [14] |

Wu X, Lang L, Ma W, et al. Non-linear effects of mean temperature and relative humidity on dengue incidence in Guangzhou, China[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2018, 628-629: 766-771. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.136 |

| [15] |

Li ZJ, Yin WW, Clements A, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of indigenous and imported dengue fever cases in Guangdong province, China[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2012, 12(1): 132-141. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-12-132 |

| [16] |

Wood SN. Generalized additive models:an introduction with R[M]. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2006: 100-202.

|

| [17] |

Stige LC, Ottersen G, Brander K, et al. Cod and climate:effect of the North Atlantic Oscillation on recruitment in the North Atlantic[J]. Mar Ecol Prog Ser, 2006, 325: 227-241. DOI:10.3354/meps325227 |

| [18] |

Jing QL, Cheng Q, Marshall JM, et al. Imported cases and minimum temperature drive dengue transmission in Guangzhou, China:evidence from ARIMAX model[J]. Epidemiol Infect, 2018, 146(10): 1226-1235. DOI:10.1017/S0950268818001176 |

| [19] |

Sun JM, Lin JF, Yan JY, et al. Dengue virus serotype 3 subtype Ⅲ, Zhejiang province, China[J]. Emerging Infect Dis, 2011, 17(2): 321-323. DOI:10.3201/eid1702.100396 |

| [20] |

Shang CS, Fang CT, Liu CM, et al. The role of imported cases and favorable meteorological conditions in the onset of dengue epidemics[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2010, 4(8): e775. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000775 |

| [21] |

Zhu GH, Xiao JP, Zhang B, et al. The spatiotemporal transmission of dengue and its driving mechanism:a case study on the 2014 dengue outbreak in Guangdong, China[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2018, 622-623: 252-259. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.314 |

| [22] |

樊景春, 刘起勇. 气候变化对登革热传播媒介影响研究进展[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2013, 34(7): 745-749. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2013.07.020 |

| [23] |

张萌, 邓爱萍, 李剑森, 等. 2012-2017年广东省登革热疫情流行特点与趋势[J]. 中国病毒病杂志, 2018, 8(4): 282-287. DOI:10.16505/j.2095-0136.2018.0067 |

| [24] |

Rossi G, Karki S, Smith RL, et al. The spread of mosquito-borne viruses in modern times:a spatio-temporal analysis of dengue and chikungunya[J]. Spat Spatio-temporal Epidemiol, 2018, 26: 113-125. DOI:10.1016/j.sste.2018.06.002 |

| [25] |

Patz JA, Epstein PR, Burke TA, et al. Global climate change and emerging infectious diseases[J]. JAMA, 1996, 275(3): 217-223. DOI:10.1001/jama.1996.03530270057032 |

| [26] |

Xiao FZ, Zhang Y, Deng YQ, et al. The effect of temperature on the extrinsic incubation period and infection rate of Dengue virus serotype 2 infection in Aedes albopictus[J]. Arch Virol, 2014, 159(11): 3053-3057. DOI:10.1007/s00705-014-2051-1 |

| [27] |

Farjana T, Tuno N, Higa Y. Effects of temperature and diet on development and interspecies competition in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus[J]. Med Vet Entomol, 2012, 26(2): 210-217. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2011.00971.x |

| [28] |

Focks DA, Brenner RJ, Hayes J, et al. Transmission thresholds for dengue in terms of Aedes aegypti pupae per person with discussion of their utility in source reduction efforts[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2000, 62(1): 11-18. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.11 |

| [29] |

Scott TW, Amerasinghe PH, Morrison AC, et al. Longitudinal studies of Aedes aegypti (Diptera:Culicidae) in Thailand and Puerto Rico:blood feeding frequency[J]. J Med Entomol, 2000, 37(1): 89-101. DOI:10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.89 |

| [30] |

Patz JA, Martens WJ, Focks DA, et al. Dengue fever epidemic potential as projected by general circulation models of global climate change[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 1998, 106(3): 147-153. DOI:10.1289/ehp.98106147 |

| [31] |

Schreiber KV. An investigation of relationships between climate and dengue using a water budgeting technique[J]. Int J Biometeorol, 2001, 45(2): 81-89. DOI:10.1007/s004840100090 |

| [32] |

Wu PC, Lay JG, Guo HR, et al. Higher temperature and urbanization affect the spatial patterns of dengue fever transmission in subtropical Taiwan[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2009, 407(7): 2224-2233. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.11.034 |

| [33] |

Åström C, Rocklöv J, Hales S, et al. Potential distribution of dengue fever under scenarios of climate change and economic development[J]. Ecohealth, 2012, 9(4): 448-454. DOI:10.1007/s10393-012-0808-0 |

| [34] |

Russell RC, Currie BJ, Lindsay MD, et al. Dengue and climate change in Australia:predictions for the future should incorporate knowledge from the past[J]. Med J Aust, 2009, 190(5): 265-268. |

| [35] |

Githeko AK, Lindsay SW, Confalonieri UE, et al. Climate change and vector-borne diseases:a regional analysis[J]. Bull World Health Organ, 2000, 78(9): 1136-1147. |

| [36] |

Morin CW, Comrie AC, Ernst K. Climate and dengue transmission:evidence and implications[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2013, 121(11/12): 1264-1272. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1306556 |

2019, Vol. 30

2019, Vol. 30