扩展功能

文章信息

- 潘智华, 郑辰, 陈家旭, 郑葵阳, 刘相叶

- PAN Zhi-hua, ZHENG Chen, CHEN Jia-xu, ZHENG Kui-yang, LIU Xiang-ye

- 田鼠巴贝西虫感染致宿主血小板活化初步研究

- Primary characterization of platelet activation derived from mice infected by Babesia microti

- 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2018, 29(1): 34-37

- Chin J Vector Biol & Control, 2018, 29(1): 34-37

- 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2018.01.009

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-08-21

- 网络出版时间: 2017-12-12 11:27

2 徐州医科大学形态学教学实验中心, 江苏 徐州 221004;

3 中国疾病预防控制中心寄生虫病预防控制所, 卫生部寄生虫病原与媒介生物学重点实验室, 世界卫生组织疟疾、血吸虫病和丝虫病合作中心, 上海 200025

2 Experimental Teaching Center of Morphology, Xuzhou Medical University;

3 National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Key Laboratory of Parasite and Vector Biology, Ministry of Health of China, WHO Collaborating Centre for Malaria, Schistosomiasis and Filariasis

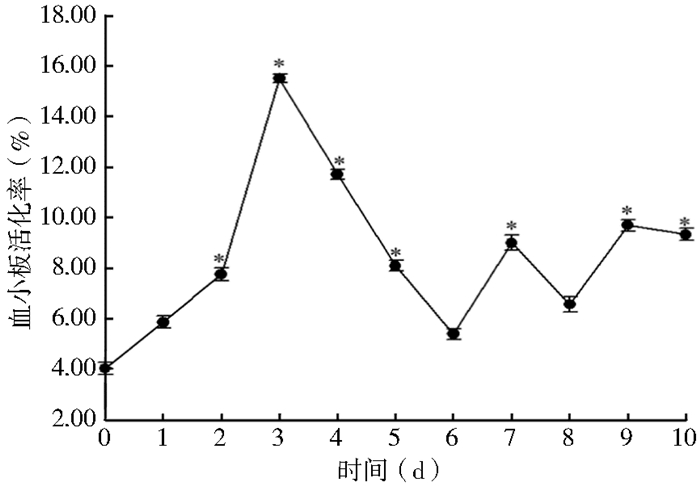

巴贝西虫病是由寄生于宿主红细胞内的巴贝西虫(Babesia)引起的血液性寄生虫病,主要通过硬蜱在人和动物间传播[1],可致患者出现溶血性贫血、器官衰竭甚至死亡,成为世界性的人类新发寄生虫病而倍受关注和重视[2-3]。田鼠巴贝西虫(B. microti)为引起人巴贝西虫病的主要病原体,目前,巴贝西虫病分布范围较广,在美洲、欧洲和亚洲均有病例报道[4-7]。

血小板是参与凝血过程的重要调节因子,活化的血小板除参与凝血外,在感染性疾病的免疫调节和炎症反应中也有重要作用[8-9]。近年来,关于血小板活化在寄生虫致病及寄生虫病治疗中的作用研究显著增多[10-12]。文献报道,宿主感染疟原虫(Plasmodium)后24 h内血小板即可活化;活化后的血小板可诱导机体产生急性期反应蛋白,如血清淀粉蛋白-P、C反应蛋白等;急性反应蛋白与染虫红细胞结合后可减少宿主体内的虫荷[13]。此外,在感染疟原虫的脑型疟小鼠模型中,红细胞染虫率随血小板活化率的升高而升高[14]。虽有研究发现,犬感染罗氏巴贝西虫(B. rossi)后血小板活化率明显升高[15],但田鼠巴贝西虫感染宿主后血小板的活化及其与红细胞染虫率的关系研究较少。血小板活化后各种颗粒内容物和特异膜蛋白被释放至血浆中或表达在血小板膜表面。血小板膜表面有多种糖蛋白,主要包括溶酶体膜蛋白(如CD63)和血小板颗粒膜糖蛋白(如CD62P)。CD62P也称为颗粒膜蛋白、P选择素和血小板活化依赖性颗粒外膜蛋白,是目前已知最能直观地反映血小板活化程度的特异指标之一,被认为是检测活化血小板标志物的金标准[16-17]。本研究利用流式细胞术以CD62P抗体检测田鼠巴贝西虫感染宿主后血小板的活化率,利用吉姆萨染色检测田鼠巴贝西虫感染后宿主红细胞的染虫率,研究两者间的相关性,为探讨血小板活化在田鼠巴贝西虫致病中的作用奠定基础。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料田鼠巴贝西虫(ATCC PRA-99TM)由中国CDC寄生虫病预防控制所提供;4~6周龄雌性BALB/c小鼠和体质量18~20 g的雌性NOD/SCID小鼠均购自北京华阜康实验动物技术有限公司,饲养于徐州医科大学SPF级实验动物中心。

1.2 试剂和仪器吉姆萨染液购自南京建成生物工程研究所;异硫氰酸荧光素(FITC)标记的小鼠CD62P抗体、藻红蛋白(PE)标记的小鼠CD61抗体均为美国BD公司产品;其他试剂均为国产分析纯产品。FACSCantoTMⅡ型流式细胞仪为美国BD公司产品。

1.3 方法 1.3.1 田鼠巴贝西虫感染动物的制备将60只4~6周龄的雌性BALB/c小鼠随机平均分成2组;根据文献[18],将田鼠巴贝西虫红细胞染虫率为60%的感染种鼠乙二胺四乙酸(EDTA)抗凝血与0.9%氯化钠溶液按1:3比例混合后,腹腔接种实验组小鼠;对照组注射等量0.9%氯化钠溶液。自感染后第1天开始,每天采集实验组(3只/d)和对照组(3只/d)BALB/c小鼠尾静脉血,制作血涂片,用于检查外周血红细胞的染虫率;采集BALB/c小鼠眼眶血于含4%枸橼酸钠的1.5 ml EP管中,充分混匀后立即置流式细胞仪检测。

1.3.2 活化血小板的标记与检测分别取实验组和对照组小鼠抗凝全血(20 μl/只),加入2 μl CD61-PE抗体,4 μl CD62P-FITC抗体;4 ℃避光染色30 min;PBS溶液洗涤后,于4 ℃ 600×g离心5 min,重悬于1 ml PBS溶液中。处理好的样品在30 min内置流式细胞仪检测。

1.3.3 红细胞染虫率的检测将1.3.1制备的血涂片,用甲醇固定晾干后,用10%吉姆萨染液染色15 min,置油镜下观察正常红细胞和染虫红细胞数量;观察的每只小鼠红细胞总数>500个。

|

采用SPSS 19.0软件进行统计学分析,数据用均数±标准差(x± s)表示;两组数据间的比较采用t检验,相关性分析使用Pearson相关性检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

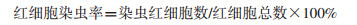

2 结果 2.1 活化血小板的确定从FSC-SCC散点图中圈出血小板群P1(图 1A),从P1中圈出CD61阳性血小板P2(图 1B),再从P2中圈出CD62P阳性血小板P3为活化血小板(图 1C、D),血小板活化率为P3占P2的百分比。

|

| 注:A. FSC-SCC散点图;B. CD61阳性细胞散点图;C.对照组CD62P阳性细胞散点图;D.感染田鼠巴贝西虫3 d后CD62P阳性细胞散点图 图 1 活化血小板流式细胞术检测 Figure 1 Activated platelets detected by flow cytometry |

| |

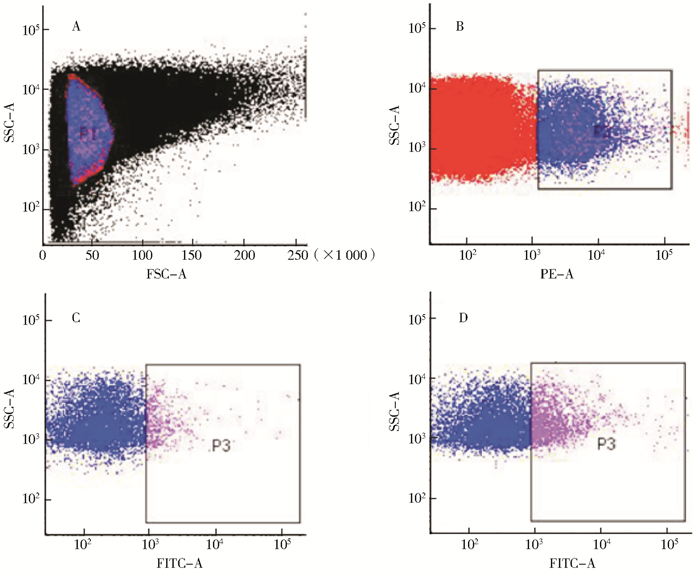

BALB/c小鼠感染田鼠巴贝西虫后,其外周血中血小板的活化率高于对照组;且在感染后第3天达到最高值,为(15.50±0.17)%,第4天开始下降,至第6天恢复至感染前水平,随后出现波动式变化(图 2);而对照组小鼠血小板活化率始终维持在(4.30±0.20)%。

|

| 注:*.与第0天比较,P<0.05;血小板活化率为x± s,n=3 图 2 BALB/c小鼠感染田鼠巴贝西虫后的血小板活化率 Figure 2 Platelet activation of mouse infected by Babesia microti |

| |

BALB/c小鼠感染田鼠巴贝西虫后,第1天即可在外周血中检测到虫体,且红细胞染虫率随时间延长逐渐升高,在感染后第8天达到最高值,为(63.10±3.43)%;第9天开始逐渐下降,见图 3。

|

| 注:*.与第1天比较,P<0.05;红细胞染虫率为x± s,n=3 图 3 小鼠感染田鼠巴贝西虫后的红细胞染虫率 Figure 3 The percentage of parasitized red blood cells derived from Babesia microti infected mice |

| |

将血小板活化率与红细胞染虫率进行Pearson相关性分析发现,两者差异无统计学意义(r=-0.101,P=0.768)。

3 讨论巴贝西虫病作为一种世界范围内流行的人兽共患病,近年来在我国的病例报道逐渐增加,引起广泛重视[19]。对田鼠巴贝西虫的研究虽然取得了一定进展,但对于其入侵红细胞机制及感染后宿主免疫反应研究甚少。巴贝西虫和疟原虫均为红细胞内寄生原虫,可引起宿主相似的免疫反应和临床症状。研究表明,血小板活化在恶性疟原虫(P. falciparum)所致脑型疟致病中起重要作用[20]。因此,本研究利用流式细胞术对田鼠巴贝西虫感染小鼠外周血中血小板活化情况进行动态追踪,并初步探讨其与外周血红细胞染虫率的关系,以期发现血小板活化在巴贝西虫病致病过程中的作用。

血小板活化可以引起恶性疟原虫感染红细胞黏附,使血流变慢,促进凝血,从而易于虫体侵入其他正常红细胞[21-22]。此外,在小鼠脑型疟感染后24 h内使用血小板抑制剂可有效降低小鼠的红细胞染虫率,从而提高其存活率[14]。本研究结果表明,BALB/c小鼠在感染田鼠巴贝西虫后的第3天,血小板活化率最高,之后开始下降,第6、7天血小板活化率与对照组无明显差异,且出现波动变化,规律性不明显。提示田鼠巴贝西虫感染后前3 d为血小板活化的关键时期,若在该时期有效地阻止血小板活化可能会阻止虫体进一步入侵正常红细胞,从而降低红细胞染虫率,减轻感染程度。

本研究发现,BALB/c小鼠在感染田鼠巴贝西虫后红细胞染虫率逐渐升高,在第8天达到最高值,之后开始逐渐下降,与其他文献报道一致[23]。虽然感染后前3 d血小板活化率和红细胞染虫率均呈上升趋势,但血小板活化率与红细胞染虫率的变化无明显相关性,可能与血液循环中活化血小板半衰期短,清除加速,超过其产生速度以及免疫应答造成的血小板破坏而导致血小板减少有关[24-25]。感染疟原虫的患者红细胞染虫率与大多数血液学参数具有相关性,包括中性粒细胞、嗜酸性粒细胞、淋巴细胞和血小板等[26]。因此,红细胞染虫率的变化可能与机体复杂的免疫应答机制有关,并非血小板活化单一作用的结果。

本研究对小鼠感染田鼠巴贝西虫后血小板活化情况发现及其与红细胞染虫率的变化关系进行了初步研究,为研究田鼠巴贝西虫的致病机制开拓了新思路。

| [1] |

Vannier E, Krause PJ. Human babesiosis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 366(25): 2397-2407. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1202018 |

| [2] |

Vannier E, Krause PJ. Babesiosis in China, an emerging threat[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(2): 137-139. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71062-X |

| [3] |

Fang LQ, Liu K, Li XL, et al. Emerging tick-borne infections in mainland China:an increasing public health threat[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015, 15(12): 1467-1479. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00177-2 |

| [4] |

Lemieux JE, Tran AD, Freimark L, et al. A global map of genetic diversity in Babesia microti reveals strong population structure and identifies variants associated with clinical relapse[J]. Nat Microbiol, 2016, 1(7): 16079. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.79 |

| [5] |

Obiegala A, Pfeffer M, Pfister K, et al. Molecular examinations of Babesia microti in rodents and rodent-attached ticks from urban and sylvatic habitats in Germany[J]. Ticks Tick Borne Dis, 2015, 6(4): 445-449. DOI:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.03.005 |

| [6] |

Bullard JM, Ahsanuddin AN, Perry AM, et al. The first case of locally acquired tick-borne Babesia microti infection in Canada[J]. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol, 2014, 25(6): e87-89. |

| [7] |

Tuvshintulga B, Sivakumar T, Battsetseg B, et al. The PCR detection and phylogenetic characterization of Babesia microti in questing ticks in Mongolia[J]. Parasitol Int, 2015, 64(6): 527-532. DOI:10.1016/j.parint.2015.07.007 |

| [8] |

Smyth SS, McEver RP, Weyrich AS, et al. Platelet functions beyond hemostasis[J]. J Thromb Haemost, 2009, 7(11): 1759-1766. DOI:10.1111/jth.2009.7.issue-11 |

| [9] |

Czapiga M, Kirk AD, Lekstrom-Himes J, et al. Platelets deliver costimulatory signals to antigen-presenting cells:a potential bridge between injury and immune activation[J]. Exp Hematol, 2004, 32(2): 135-139. DOI:10.1016/j.exphem.2003.11.004 |

| [10] |

Sharma J, Eickhoff CS, Hoft DF, et al. Absence of calcium-independent phospholipase A2β impairs platelet-activating factor production and inflammatory cell recruitment in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected endothelial cells[J]. Physiol Rep, 2014, 2(1): e00196. DOI:10.1002/phy2.196 |

| [11] |

Goncalves R, Zhang X, Cohen H, et al. Platelet activation attracts a subpopulation of effector monocytes to sites of Leishmania major infection[J]. J Exp Med, 2011, 208(6): 1253-1265. DOI:10.1084/jem.20101751 |

| [12] |

McMorran BJ, Wieczorski L, Drysdale KE, et al. Platelet factor 4 and Duffy antigen required for platelet killing of Plasmodium falciparum[J]. Science, 2012, 338(6112): 1348-1351. DOI:10.1126/science.1228892 |

| [13] |

McMorran BJ, Marshall VM, de Graaf C, et al. Platelets kill intraerythrocytic malarial parasites and mediate survival to infection[J]. Science, 2009, 323(5915): 797-800. DOI:10.1126/science.1166296 |

| [14] |

Aggrey AA, Srivastava K, Ture S, et al. Platelet induction of the acute-phase response is protective in murine experimental cerebral malaria[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 190(9): 4685-4691. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1202672 |

| [15] |

Goddard A, Leisewitz AL, Kristensen AT, et al. Platelet activation and platelet-leukocyte interaction in dogs naturally infected with Babesia rossi[J]. Vet J, 2015, 205(3): 387-392. DOI:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.05.008 |

| [16] |

Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Krueger LA, et al. Circulating monocyte-platelet aggregates are a more sensitive marker of in vivo platelet activation than platelet surface P-selection:studies in baboons, human coronary intervention, and human acute myocardial infarction[J]. Circulation, 2001, 104(13): 1533-1537. DOI:10.1161/hc3801.095588 |

| [17] |

Moritz A, Walcheck BK, Weiss DJ. Flow cytometric detection of activated platelets in the dog[J]. Vet Clin Pathol, 2003, 32(1): 6-12. DOI:10.1111/vcp.2003.32.issue-1 |

| [18] |

张加, 司晨晨, 蔡玉春, 等. 田鼠巴贝虫可溶性抗原组分分析及其初步应用[J]. 中国人兽共患病学报, 2014, 30(5): 469-478. |

| [19] |

Zhou X, Xia S, Huang JL, et al. Human babesiosis, an emerging tick-borne disease in the people's republic of China[J]. Parasit Vectors, 2014, 7: 509. |

| [20] |

Emuchay CI, Usanga EA. Increased platelet factor 3 activity in Plasmodium falciparum malaria[J]. East Afr Med J, 1997, 74(8): 527-529. |

| [21] |

Pain A, Ferguson DJP, Kai O, et al. Platelet-mediated clumping of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes is a common adhesive phenotype and is associated with severe malaria[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(4): 1805-1810. DOI:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1805 |

| [22] |

Chotivanich K, Sritabal J, Udomsangpetch R, et al. Platelet-induced autoagglutination of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells and disease severity in Thailand[J]. J Infect Dis, 2004, 189(6): 1052-1055. DOI:10.1086/jid.2004.189.issue-6 |

| [23] |

魏金龙, 周勇志, 龚海燕, 等. 田鼠巴贝斯虫感染对宿主凝血系统的影响[J]. 中国兽医科学, 2015, 45(4): 390-394. |

| [24] |

Piguet PF, Kan CD, Vesin C. Thrombocytopenia in an animal model of malaria is associated with an increased caspase-mediated death of thrombocytes[J]. Apoptosis, 2002, 7(2): 91-98. DOI:10.1023/A:1014341611412 |

| [25] |

Gramaglia I, Sahlin H, Nolan JP, et al. Cell-rather than antibody-mediated immunity leads to the development of profound thrombocytopenia during experimental Plasmodium berghei malaria[J]. J Immunol, 2005, 175(11): 7699-7707. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7699 |

| [26] |

Evelyn ME, Ezeiruaku F, Ukaji DC. Experiential relationship between malaria parasite density and some haematological parameters in malaria infected male subjects in Port Harcourt, Nigeria[J]. Glob J Health Sci, 2012, 4(4): 139-148. |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29