扩展功能

文章信息

- 徐鹏, 张雪飞, 赵志军, 马英

- XU Peng, ZHANG Xue-fei, ZHAO Zhi-jun, MA Ying

- 野生动物粪便微生物宏基因组学研究进展

- Research progress in metagenomics of fecal microorganisms in wild animals

- 中国媒介生物学及控制杂志, 2022, 33(3): 446-452

- Chin J Vector Biol & Control, 2022, 33(3): 446-452

- 10.11853/j.issn.1003.8280.2022.03.026

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2021-12-18

2 青海省地方病预防控制所, 青海 西宁 811602

2 Qinghai Institute for Endemic Disease Control and Prevention, Xining, Qinghai 811602, China

近年来,随着国家加大对野生动物与自然环境的保护力度,野生动物的数量不断增加。但是,随着城市化进程的加剧,人类活动、居住的范围越来越大,野生动物不得不与人类共享某些生存环境,这使得人类接触一些野生动物的机会大大增加。这些接触为病毒、细菌的跨物种传播提供了大量机会,通过动物的尿液、粪便或者体表寄生节肢动物如蜱类、螨类、蚤类等将贝纳柯克斯体、汉坦病毒、鼠疫耶尔森菌等传播给人类[1]。野生动物间、野生动物与人之间的传染病防治则成为了主要的防控要点。基于研究病原微生物和保护野生动物的双重考虑,应用宏基因组学研究野生动物粪便微生物,既不会对野生动物造成伤害,又可以在一定程度上了解野生动物体内微生物群落组成、种间进化关系、群落多样性以及与宿主动物的共生和共进化关系;也可以监测一些致病性微生物、病毒等,有利于医疗卫生工作者快速应对由这些野生动物引发的一些突发性公共卫生事件;同时还可用于挖掘及鉴定野生动物体内一些潜在的、未曾发现的微生物种类。因此,本文对一些常见的野生动物粪便菌群的宏基因组研究进行综述,展望未来的发展趋势与研究重点,为防治与诊断由于接触野生动物引起的疾病提供理论支持。

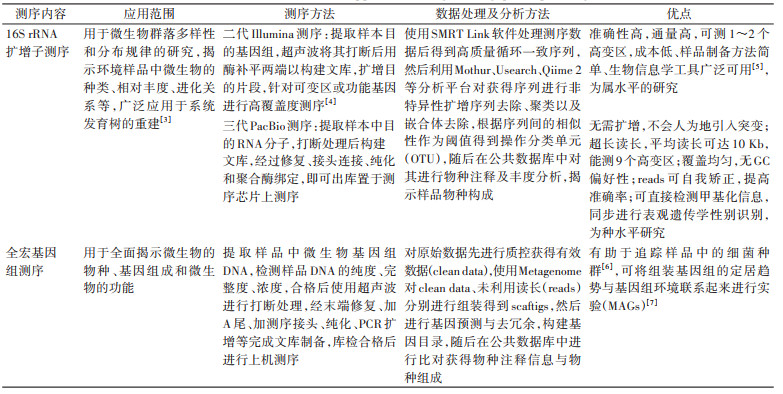

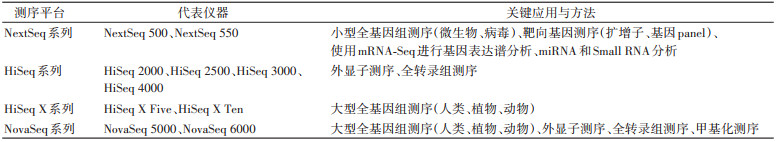

1 宏基因组学概述宏基因组学(metagenomics)又称生态基因组学(ecogenomics)、环境基因组学(environmental genomics)或者群落基因组学(community genomics),为研究宏基因组的一门学科。在1998年,Handelsman等[2]首次提出“宏基因组”的概念。宏基因组起初是作为一种工具开发的,用于对环境样本中所包含的微生物基因组进行功能性和序列性的分析,现阶段则发展为应用现代分子生物学技术,从环境中得到目的微生物群落基因组。其中高通量测序技术在目前使用最广泛,可应用于所有的基因组类型,主要测序内容为16S rRNA扩增子或全宏基因组(表 1),主要测序平台则根据每个平台的优势来选择。见表 2。

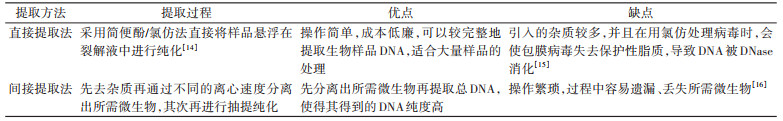

16S rRNA扩增子测序(16S rRNA amplicon sequencing),通常是通过不同实验方法得到的样品需先提取基因组中DNA,使用物理化学方法破碎生物样品,溶于含有一定量体积的DNaseⅠ(脱氧核糖核酸酶Ⅰ)缓冲液和DNaseⅠ中,使其释放DNA[8],接着利用氯化铯密度梯度超速离心、色谱法、电泳法、过滤法、透析法等进行分析纯化,该方法避免了先培养微生物再利用培养微生物进行DNA提取的复杂过程[9],其提取方法分为直接提取法与间接提取法,提取过程及优缺点见表 3。提取完成后用超声波将其随机打断,用酶将其两端补平用于连接已知的接头序列,添加完接头序列的DNA片段集合即为样品的DNA文库,随后在构建好的文库中进行目的基因的筛选,筛选方法目前分为两大类,一类为表型筛选,另一类为基因型分析[10]。表型筛选利用模式微生物上的表型变化去筛选某些目的基因,在实验中常用功能驱动筛选(function-driven screening)与序列驱动筛选(sequence-driven screening),前者利用各种选择培养基上的特殊表征型的淀粉酶、抗生素抗性基因克隆子进行筛选[11],后者则利用已知保守序列设计引物或探针,使用杂交、PCR的手段筛选目的基因[12]。基因型分析则是对文库中的某些DNA进行测序分析,多用于评估生境的多样性,底物诱导基因表达筛选(substrate induced gene exprssion screening,SIGEX)是基因型分析的常用方法,其利用在底物存在的情况下,编码分解代谢途径的基因存在于受底物诱导的操纵子中这一原理,来筛选某些基因[13]。筛选好目的基因后在流动池(Flowcell)中完成目的基因片段的扩增。然后对其进行上机测序,完成数据的处理与统计。

|

全宏基因组测序(whole metagenomics sequencing)是一种直接对微生物群体中包含的全部基因组信息进行研究的手段,绕过了对微生物个体进行分离培养的过程,应用基因组学技术直接对自然环境中的微生物群落进行研究,提供了对无法分离培养的微生物进行研究的途径,避免了实验过程中由于环境改变引起微生物序列变化所带来的偏差。在实际应用过程中与扩增子测序一样,首先也需要提取样品DNA,提取之后使用琼脂糖凝胶电泳(AGE)分析DNA纯度与完整性、使用Qubit对DNA浓度进行精确定量以完成对提取DNA的检测,合格后的样品用超声波将其打断成长度约为359 Kb的片段,经末端修复、加A尾、加测序接头、纯化、PCR扩增等完成文库制备。文库构建完成后稀释文库,使用Qubit进行初步定量,随后对文库的插入片段(insert size)进行检测,符合预期后使用实时定量PCR(qPCR)方法对文库的有效浓度进行准确定量,以保证文库的质量满足后续分析要求。库检合格后,把不同文库按照有效浓度及对目标数据量的需求混合(pooling)后进行上机测序。

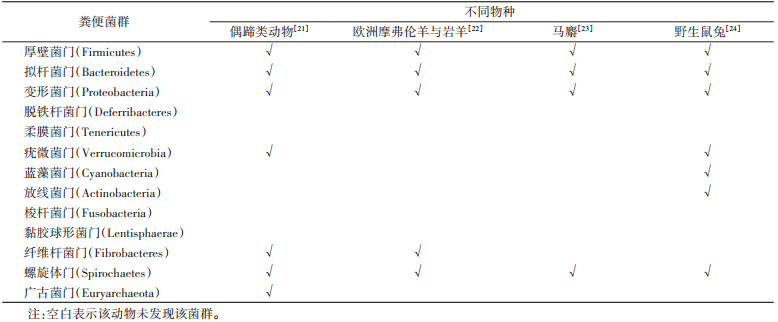

3 宏基因组学在野生动物粪便微生物中的应用 3.1 野生动物粪便细菌组成及拓展研究野生动物种类繁多,本文就几种目前已研究的野生动物展开叙述(表 4)。鼠类与人类关系密切,常存在于人类生存的环境中,体内携带有多种细菌病毒。据多项研究结果平均显示,野生鼠科动物肠道中超过94%的细菌都分布在厚壁菌门、拟杆菌门和变形菌门[17],这些菌群促进了宿主对生存环境的适应性,与宿主共同进化。经过对比分析发现野生小鼠的肠道菌群不论种类还是数量都远远多于实验小鼠[18],说明动物肠道内的微生物种群、微生物功能作用受到宿主的生理与生存环境(如海拔高度、日照时长、低气压、低温、强紫外线、栖息地类型、食物结构、土壤类型、宿主生存年龄等)的不同而具有非常大的差异,其中食物结构在动物体内肠道菌群的种类与丰度上起着至关重要的作用[19],相关研究也显示饮食组成成分越相似的动物,其个体肠道菌群的组成也越接近[20]。在研究了中国西北高海拔地区放养、野生的偶蹄类啮齿动物与相近食物成分的植食性动物粪便菌群后发现,二者也具有一定的相似性。其中西北高海拔地区放养的偶蹄类动物的粪便微生物群落主要分布于7个优势菌门[21]。2019年Sun等[22]运用高通量测序技术等方法分别对山东省济南市(低海拔组)的欧洲摩弗伦羊(Ovis orientalis musimon)与青藏高原(高海拔组)岩羊(Pseudois nayaur)的粪便微生物群落进行分析,基于OTU的分析显示共测得33个门,378个属。Sun等[23]利用相同技术对马麝(Moschus chrysogaster)的粪便菌群进行分析;谭春桃等[24]对青藏高原夏季野生鼠兔的粪便菌群进行研究后发现其主要集中在7个门。

Ley等[25]对来自13个生物分类的60种哺乳动物的粪便菌群分析后发现,同种宿主的粪便微生物群落之间的相似性高于不同宿主的粪便微生物群落之间的相似性,其16S rRNA基因序列测序结果显示大多数序列属于厚壁菌门(65.7%)、拟杆菌门(16.3%)、变形菌门(8.8%)、放线菌门(4.7%)、疣微菌门(2.2%)、梭杆菌门(0.67%)。以上研究结果均利用宏基因组技术对动物粪便细菌种类进行阐述并开展拓展研究,以分析整个野生动物不同生存环境下粪便菌群所存在的一致性。

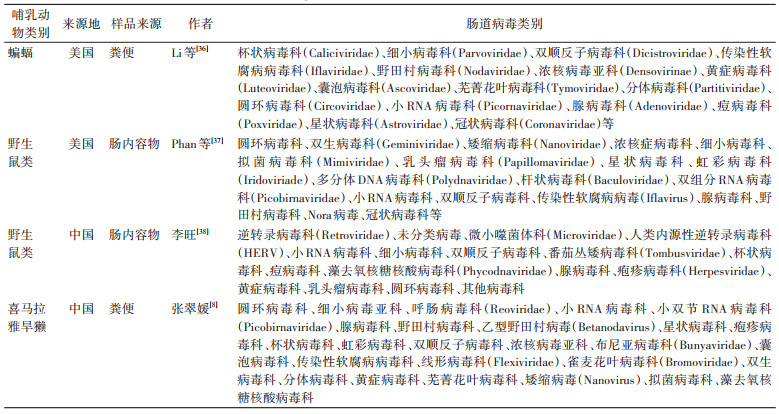

3.2 人兽共患病中相关野生动物粪便病毒组成近些年来,源于动物体内的病毒成为很多人间疾病潜在传染源。2003年发生的非典型性肺炎可能是由蝙蝠、果子狸、鼠类等野生动物将重症急性呼吸综合征(SARS)病毒传播给人引起[26];2012年在中东发生了一种类似于SARS的呼吸系统疾病,经过相关学者研究其可能来源于蝙蝠、单峰骆驼携带的一种冠状病毒[27];紧接着在2013年又出现了新型重配禽流感A(H7N9)病毒的人间传播[28],相关学者迅速展开了对该病毒的起源、系统发育和结构等的分析,并且在此之后不断有国内外学者对野生动物的肠道、粪便、唾液微生物进行研究。2019年出现的新型冠状病毒(2019-nCoV),对全球造成了极大的影响。以往研究发现冠状病毒在蝙蝠、果子狸、鼠类等野生动物体内均有携带。对2019-nCoV进行分析发现该病毒与蝙蝠体内携带的冠状病毒全基因相似性很高[29-30]。除蝙蝠、鼠类等野生动物外,穿山甲[31]也是冠状病毒的传播源。除冠状病毒外,野生动物体内的杯状病毒已经有可能结合组织血型抗原从而具备跨物种传播的条件[32]。同时,在最近10年的研究中,大量的新病毒被鉴定出来[33],与疾病相关的特定病毒分类群、病毒群对生态系统的关键贡献也在近几年才被确定,这说明对野生动物体内病毒的了解还远远不够,还有许多种病毒可以在人类与野生动物之间传播引起人兽共患病。因此,基于宏基因组学对野生动物粪便中的病毒种类进行研究,不仅可以预防一些潜在疾病,还能极大补充动物病毒库,为将来关于病毒多样性的研究作出巨大贡献[34]。

早在1978年就有学者在几内亚共和国进行野生动物传播、携带虫媒病毒的采样研究[35],对野生动物携带的病毒进行分析,为后来的学者开拓了先河;2010年,Li等[36]对来自美国加利福尼亚州和德克萨斯州的蝙蝠粪便进行分析;2011年,Phan等[37]使用宏基因组技术对美国野生鼠类进行研究,共获得了26 846条病毒序列;此后,张翠媛[8]在2016年,使用扩增子测序技术对我国喜马拉雅旱獭(Marmota himalayana)粪便标本进行处理,采用生物信息学分析,运用分子生物学、分子流行病学等方法,获得了10 074条病毒序列,这些病毒序列与10种脊椎动物病毒科有关,昆虫病毒相关序列占到了8.1%,植物病毒序列占到了12.6%,另外还有27.3%的序列与其他病毒相关;同在2016年,李旺[38]利用相同技术分析了中国江苏省泰州市的野生鼠类肠内容物的病毒DNA片段。见表 5。

不难发现,中美两国学者所检测的蝙蝠、鼠类与喜马拉雅旱獭之间具有一定的相似性。在脊椎动物病毒科方面,均检测出圆环病毒科、细小病毒亚科、小RNA病毒科、野田村病毒科、星状病毒科;昆虫相关病毒科均检测出虹彩病毒科、双顺反子病毒科、浓核病毒亚科、传染性软腐病病毒科;植物病毒科都检测出双生病毒科、矮缩病毒科;其他病毒科均检测出拟菌病毒科。同时在2010年Donaldson等[39]对北美3种蝙蝠进行粪便分析、2019年Mishra等[40]对沙特阿拉伯4个物种的72只蝙蝠进行粪便分析,其粪便病毒种类分布与Phan等[37]的分析结果都具有一定的相似性;Duarte等[41]对巴西的野生动物粪便分析中也出现了与中、美两国学者相似的病毒科。证明野生动物虽然生理与生存环境存在不同,但是病毒种类却具有一定的相似之处。

3.3 野生动物粪便可能携带的病原体野生动物体内携带的微生物彼此相辅相成,在机体各项机能指标完好时,彼此相安无事、各司其职;而在机体免疫力低下或病态时,有些细菌则快速繁殖,破坏机体内平衡,使生物体处于病态、死亡,或通过粪便、尿液等将其所携带病菌传播给人,造成人兽共患病的发生。常见的野生动物可能携带的病原体研究进展见表 6。

|

野生动物体内可以携带各种病毒却并不表现出病态的症状,而是作为一些病原体的储藏源存在于自然界中,通过粪便等将其排出体外,从而对人兽造成一些危害和威胁。近年来,科技的发展越来越快,各种现代化的交通工具使人类与野生动物的流动更加便捷和频繁,使得人类与这些携带各种病毒的动物如蝙蝠、鼠类、喜马拉雅旱獭等的接触机会越来越多,从而使这些病毒有了跨物种、跨地区传播的机会,感染疾病的概率增大。所以,我们需要在不伤害野生动物的前提下,探索充分应用宏基因学等新技术的多样性与先进性,从实验室的角度全面掌握野生动物体内微生物的种类与组成,为相关的一些疾病暴发流行提供合理的预防控制手段,最大程度地减少、降低人员的伤亡与财政损失。

利益冲突 无

| [1] |

Cutler SJ, Fooks AR, van der Poel WH. Public health threat of new, reemerging, and neglected zoonoses in the industrialized world[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2010, 16(1): 1-7. DOI:10.3201/eid1601.081467 |

| [2] |

Handelsman J, Rondon MR, Brady SF, et al. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: A new frontier for natural products[J]. Chem Biol, 1998, 5(10): R245-R249. DOI:10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90108-9 |

| [3] |

Ericsson AC, Busi SB, Amos-Landgraf JM. Characterization of the rat gut Microbiota via 16S rRNA amplicon library sequencing[M]//Hayman G, Smith J, Dwinell M, et al. Rat genomics. New York, NY: Humana, 2019, 2018: 195-212. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9581-3_9.

|

| [4] |

Walters W, Hyde ER, Berg-Lyons D, et al. Improved bacterial 16S rRNA Gene (V4 and V4-5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys[J]. mSystems, 2016, 1(1): e00009-15. DOI:10.1128/mSystems.00009-15 |

| [5] |

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data[J]. Nat Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

| [6] |

Jovel J, Patterson J, Wang WW, et al. Characterization of the gut microbiome using 16S or shotgun metagenomics[J]. Front Microbiol, 2016, 7: 459. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00459 |

| [7] |

Quince C, Walker AW, Simpson JT, et al. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2017, 35(9): 833-844. DOI:10.1038/nbt.3935 |

| [8] | |

| [9] |

Miller DN, Bryant JE, Madsen EL, et al. Evaluation and optimization of DNA extraction and purification procedures for soil and sediment samples[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1999, 65(11): 4715-4724. DOI:10.1128/AEM.65.11.4715-4724.1999 |

| [10] |

Gupta R, Beg Q, Lorenz P. Bacterial alkaline proteases: Molecular approaches and industrial applications[J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2002, 59(1): 15-32. DOI:10.1007/s00253-002-0975-y |

| [11] |

Diaz-Torres ML, McNab R, Spratt DA, et al. Novel tetracycline resistance determinant from the oral metagenome[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2003, 47(4): 1430-1432. DOI:10.1128/aac.47.4.1430-1432.2003 |

| [12] |

Desai N, Antonopoulos D, Gilbert JA, et al. From genomics to metagenomics[J]. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2012, 23(1): 72-76. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2011.12.017 |

| [13] |

张冰, 崔岱宗, 赵敏. 宏基因组学技术及其在微生物学研究中的应用[J]. 黑龙江医药, 2014, 27(2): 267-271. Zhang B, Cui DZ, Zhao M. Application of metagenomics for understanding of environmental microbiology[J]. Heilongjiang Med J, 2014, 27(2): 267-271. DOI:10.14035/j.cnki.hljyy.2014.02.001 |

| [14] |

Willner D, Furlan M, Schmieder R, et al. Metagenomic detection of phage-encoded platelet-binding factors in the human oral cavity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2011, 108(S1): 4547-4553. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1000089107 |

| [15] |

Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Method for discovering novel DNA viruses in blood using viral particle selection and shotgun sequencing[J]. Biotechniques, 2005, 39(5): 729-736. DOI:10.2144/000112019 |

| [16] |

吴莎莎, 卢向阳, 许源, 等. 宏基因组学在胃肠道微生物研究中的应用[J]. 激光生物学报, 2012, 21(1): 91-96. Wu SS, Lu XY, Xu Y, et al. The application of metagenomic in the research of the microbiology in the gastrointestinal tract[J]. Chin J Laser Biol, 2012, 21(1): 91-96. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-7146.2012.01.018 |

| [17] |

Wang J, Linnenbrink M, Künzel S, et al. Dietary history contributes to enterotype-like clustering and functional metagenomic content in the intestinal microbiome of wild mice[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2014, 111(26): E2703-E2710. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1402342111 |

| [18] |

Kreisinger J, Čížková D, Vohánka J, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiota of wild and inbred individuals of two house mouse subspecies assessed using high-throughput parallel pyrosequencing[J]. Mol Ecol, 2014, 23(20): 5048-5060. DOI:10.1111/mec.12909 |

| [19] |

De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(33): 14691-14696. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1005963107 |

| [20] |

Li H, Li TT, Beasley DE, et al. Diet diversity is associated with beta but not alpha diversity of pika gut microbiota[J]. Front Microbiol, 2016, 7: 1169. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01169 |

| [21] |

尚立强, 薛世魁, 王惜婧, 等. 西北高海拔地区放养偶蹄类动物肠道微生物多样性的宏基因组比较研究[J]. 安徽农业科学, 2019, 47(7): 98-101. Shang LQ, Xue SK, Wang XJ, et al. Metagenomic comparative study on the the intestinal microbial diversity of stocked cloven-hoofed animals in high elevation area of northwest China[J]. J Anhui Agric Sci, 2019, 47(7): 98-101. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2019.07.031 |

| [22] |

Sun GL, Zhang HH, Wei QG, et al. Comparative analyses of fecal microbiota in European mouflon (Ovis orientalis musimon) and blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) living at low or high altitudes[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 1735. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01735 |

| [23] |

Sun YW, Sun YJ, Shi ZH, et al. Gut microbiota of wild and captive alpine musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster)[J]. Front Microbiol, 2020, 10: 3156. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.03156 |

| [24] |

谭春桃, 李欢, 曲家鹏. 野生和室内饲养高原鼠兔肠道菌群多样性的比较[J]. 草业科学, 2019, 36(2): 531-539. Tan CT, Li H, Qu JP. Comparison of gut microbial diversity between wild and laboratory-reared plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae)[J]. Pratacult Sci, 2019, 36(2): 531-539. DOI:10.11829/j.issn.1001-0629.2018-0324 |

| [25] |

Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes[J]. Science, 2008, 320(5883): 1647-1651. DOI:10.1126/science.1155725 |

| [26] |

Lau SKP, Woo PCY, Li KSM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2005, 102(39): 14040-14045. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0506735102 |

| [27] |

Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Müller MA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: A comparative serological study[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13(10): 859-866. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6 |

| [28] |

Gao RB, Cao B, Hu YW, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368(20): 1888-1897. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1304459 |

| [29] |

Lu RJ, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10224): 565-574. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 |

| [30] |

Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin[J]. Nature, 2020, 579(7798): 270-273. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 |

| [31] |

Liu P, Chen W, Chen JP. Viral metagenomics revealed Sendai virus and coronavirus infection of Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica)[J]. Viruses, 2019, 11(11): 979. DOI:10.3390/v11110979 |

| [32] |

Kocher JF, Lindesmith LC, Debbink K, et al. Bat caliciviruses and human noroviruses are antigenically similar and have overlapping histo-blood group antigen binding profiles[J]. mBio, 2018, 9(3): e00869-18. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00869-18 |

| [33] |

Sachsenröder J, Braun A, Machnowska P, et al. Metagenomic identification of novel enteric viruses in urban wild rats and genome characterization of a group A rotavirus[J]. J Gen Virol, 2014, 95(12): 2734-2747. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.070029-0 |

| [34] |

Simmonds P, Adams MJ, Benkő M, et al. Virus taxonomy in the age of metagenomics[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2017, 15(3): 161-168. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.177 |

| [35] |

Konstantinov OK, Diallo SM, Inapogi AP, et al. The mammals of Guinea as reservoirs and carriers of arboviruses[J]. Med Parazitol (Mosk), 2006(1): 34-39. |

| [36] |

Li LL, Victoria JG, Wang CL, et al. Bat guano virome: Predominance of dietary viruses from insects and plants plus novel mammalian viruses[J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(14): 6955-6965. DOI:10.1128/JVI.00501-10 |

| [37] |

Phan TG, Kapusinszky B, Wang CL, et al. The fecal viral flora of wild rodents[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2011, 7(9): e1002218. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002218 |

| [38] |

李旺. 鼠肠道病毒宏基因组学研究[D]. 镇江: 江苏大学, 2016. DOI: 10.7666/d.D01003085. Li W. Identification of the intestinal virome of rats using viral metagenomics[D]. Zhenjiang: Jiangsu University, 2016. DOI: 10.7666/d.D01003085.(in Chinese) |

| [39] |

Donaldson EF, Haskew AN, Gates JE, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the viromes of three North American bat species: Viral diversity among different bat species that share a common habitat[J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(24): 13004-13018. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01255-10 |

| [40] |

Mishra N, Fagbo SF, Alagaili AN, et al. A viral metagenomic survey identifies known and novel mammalian viruses in bats from Saudi Arabia[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(4): e0214227. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0214227 |

| [41] |

Duarte MA, Silva JMF, Brito CR, et al. Faecal virome analysis of wild animals from Brazil[J]. Viruses, 2019, 11(9): 803. DOI:10.3390/v11090803 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33