2. 中国科学院青藏高原地球科学卓越创新中心, 北京 100101;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. CAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Science, Beijing 100101, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

物候是生物随时间变化的周期性现象,主要受生物和非生物因素驱动[1]。植物物候对陆地生态系统变化具有重要的指示作用,是气候变化的敏感指示器[2]。相对于生态学其他方向的研究,物候的观测可以更简单方便地追踪植物对气候变化的响应[2]。无论是物种尺度还是整个生态系统尺度,物候观测已经成为评估气候变化效应的一种重要科学手段[3-4],其重要性随着全球变化而日趋显著[4]。因其与气候变化(如温度和水分的改变)存在高度相关性[5],所以通过长期观测[6]、控制实验[7-8]以及遥感或模型[9-10]等方法研究物候变化可以用于重建过去的气候以及预测未来气候变化对植物的影响[11]。

气候变化主要表现为温度上升和水分有效性的变化,已对全球生态系统产生了重要的影响[6, 12]。过去的30年间,地球表面平均温度每10年上升0.2 ℃[13],未来会以更快的速度增加[14],而高寒区域的变化幅度更大[15],再加上该区域对气候变化的高度敏感性[16-17],使其成为研究物候变化的理想场所。为了深入理解气候变化对植物物候的影响,本文系统综述气候变化对高寒区域植物地上、地下物候的影响及其可能的影响因子,并就未来植物物候研究的方向提出一些建议。

1 气候变化对物候的影响高寒区域植物物候受很多环境因素的影响,包括温度、冬天的寒冷程度、土壤水分或降水、融雪时间和光周期等[18-20]。尽管高寒区域植物已经适应了低温寒冷[21],但是仍然生活在最适温度以下[22]。因此,即使小幅度的增温也能够显著加速植物生长并提高它们的繁殖力[23]。草本植物是高寒区域的主要植物类群,对气候变化的响应比木本植物更敏感[24]。因此,本文主要综述高寒区域草本植物物候对气候变化的响应研究。

高寒区域主要指高纬度和高海拔区域。高纬度区域通常被定义为南北纬60°到南北极之间,也有观点认为北半球50°以北的区域均为高纬度区域,该区域具有季节间昼夜长度变化较大的特点[25]。高海拔区域是指树线以上的区域[16]。该区域的植物物候研究主要集中在洛基山[16]、阿尔卑斯山[26]以及青藏高原[6-7, 9, 27]等地区。与其他生境不同,该区域植物主要受低温、雪融时间、较低的光合活性以及短暂的生长期等因素制约[16]。因此,高寒区域可能会因快速的增温以及水分有效性的改变而显著影响植物物候[8, 19, 28-29]。

1.1 气候变化对个体地上物候的影响物候的变化取决于多种环境因子,然而在众多的因子中,温度所起的作用最大[17],因为它是影响植物生长发育时间最长并且起主导作用的因子[17, 30]。对个体地上物候的研究而言,大多数的长期地面观测和增温控制实验发现:随着持续增温,返青期或初花期显著提前,秋季枯黄期显著延迟,从而延长了植物生长季[6-7, 17, 19, 31-36]。例如,全球14个站点的长期地面观测表明每升高1 ℃返青期和初花期提前>4.6 d[17]。但是植物早期物候初始期的提前可能会增加其遭受霜害的风险,造成植物组织细胞的损伤[37]。持续增温也可能导致植物无法满足低温需求,从而延迟物候期[36]。例如,有研究发现秋季变暖会延迟下一年的初花期(延迟2.54 d·℃-1)[36]。然而Jiang等[27]在青藏高原研究发现,与其他物候期相比,果期物候对短期增温和降温的响应保持相对稳定性,这可能是植物维持种子成熟以及传播成功的机制。但也有人认为增温下初果期的变化是存在物种差异的[32]。对晚期物候而言,比如枯黄期,对气候变化的响应被认为仍然存在很多不确定性[4]。例如,Arft等[29]分析高寒区域13个站点的物候数据发现增温对枯黄期的影响很小,认为是光周期决定了高寒区域植物枯黄期的变化。除物候初始期外,持续期的变化也是植物物候的重要特征[6, 32, 38]。但目前对持续期的研究较少[6, 32],有研究认为物候持续期变化的温度敏感性要低于初始期[6, 38-39]。另外,营养生长和繁殖生长之间的长度变化是存在权衡的[6],并且这种权衡会决定植物进化的方向和过程[31, 40]。比如在高纬低暖区域,植物会将更多的资源投入到营养生长中,这可能是植物本身的一种保守策略,以获取更多的如光照、养分等资源,增加植物在群落中的竞争力;而在高纬高冷区域,植物会将更多的资源投入到生殖生长中,以占领更多的裸地[29]。

持续的增温和降雨模式的改变将会显著影响高寒生态系统的季节变化模式。然而有研究认为物候的提前更多是依赖于水分有效性而不是温度[41]。因为在空间和时间上温度可能会引起植物物候的渐变,而降水变化则会引起物候的突变,很大程度上决定物候初始期的早晚[42]。但是当前大多数研究聚焦于温度对物候的影响,较少关注降雨的效应[34, 42]。目前研究认为冬春季降水模式变化对物候产生了显著的影响[43]。例如,吕新苗等[44]发现,虽然与上一年相比气温偏低,但因降雨提前使得纳木错高寒草甸物候期提前约20 d。降雨对物候初始期(返青期和初花期)的效应不仅存在于干旱区,对湿润区也同样会产生重要的影响[25]。尤其是当前持续增温以及CO2浓度增加显著地延长植物生命周期的现状下,水分的重要性更加凸显[45]。

雪融时间也是影响物候变化的重要因素。雪融时间主要通过光合有效辐射、温度和水分有效性的变化影响植物物候的变化[28],它包含春季温度变化和秋冬积雪量的信息[20]。因此,雪融时间被认为与植物的早期物候存在很大的相关性[28],尤其对以地中海气候为特征的洛基山区域而言[27, 46]。研究发现多数植物能够在雪融后迅速返青和开花[8, 12],因为这能够为植物的早期生命活动提供充足的水源[47]。所以返青期也可能会随积雪厚度的增加而提前[48]。而在积雪覆盖较少的区域却不会受雪融时间影响,比如青藏高原[7-8]。但这往往会影响植物的开花时间,因为只有达到植物所需的土壤水分后才会开花[49]。Woodley和Svoboda[50]通过积雪移除实验也发现类似的趋势。积雪不仅能为植物的早期生命活动提供水源,也能起到很好的保温作用[51],所以有些草本植物仍然能够在雪被下返青[52]。但这可能会导致植物的耐寒性减弱[53]。另一方面,它的保温作用也可能会增加地下根系的呼吸消耗,因为地下根系在0 ℃时仍然有活性,直到降至-5~-10 ℃时才会进入休眠[54]。所以积雪晚融可能对植物的早期生长更有利[55],因为积雪过早融化可能会引起生长季早期的干旱以及土壤解冻时间的延长[56]。积雪厚度和雪融时间不仅影响初花期,而且也显著地影响群落的物种丰富度和物候持续期[20]。值得注意的是,虽然增温使得雪融时间不断提前[12],但冬季降水量也会显著增加,二者的净效应可能会使得雪融时间并没有显著的变化[35]。所以,物候期也不会发生显著的变化。

1.2 气候变化对群落地上物候的影响无论是地面观测还是遥感,大多数研究均发现春季变暖能够显著提前群落早期物候[10, 33, 57]。例如,基于遥感方法研究群落物候发现,增温使得阿拉斯加区域植被返青期自1975年到2000年提前了近10 d,西伯利亚苔原区也出现类似的趋势[30]。虽然持续的增温能够提前返青期,但年均温每增加1 ℃,返青临界温度会提高约0.8 ℃,并且高海拔植物相对于低海拔具有更高的返青临界温度[9],这可能是因为植物逐渐适应了增温[46]。但也有研究发现早期物候对增温的响应程度不大甚至表现出延迟的趋势[58-59]。然而,对这些结果的解释却存在很大差异,Yu等[48]认为是由于冬季增温使植物无法满足春化阶段对低温的需求,从而延迟了返青期;Yi和Zhou[60]则认为可能与大气污染特别是气溶胶的增加有关;也有人认为延迟的原因与植被退化导致的盖度降低有关,因为裸地会提高地表反射率,从而使气温降低,这种效应在春季尤为显著[61]。由于高寒地区下垫面以存在季节性冻土和永久性冻土为特征,而植被盖度下降会引起季节性冻土的融化时间提前,但同时也会提前其冻结时间[61]。因此,高寒区域植被盖度下降可能会提前枯黄期,而增温却可以延迟苔原植被的枯黄期[62]。例如,Jeong等[10]发现北半球区域的植被枯黄期在不同时期分别延迟2.3 d (1982—1999年)和4.3 d (2000—2008年)。与之相反,有人却认为增温导致植被枯黄期的提前[63]。出现这些差异的原因可能与水分变化有关,因为暖干化会导致植被枯黄期提前[56]。然而,与物种水平相似的是,也有人认为光周期的影响要超过温度[62]。总之,相对于其他物候期,决定枯黄期的因素仍然存在争议[4],还需要广泛的研究。

与温度的效应不同,地面观测研究报道水分变化对群落返青期并没有产生显著的影响[32, 64]。然而初花期却受水分影响较大,这可能与植物在繁殖期会消耗较多的水分有关[65]。对群落持续期而言,多数研究认为干旱会缩短花蕾、开花以及果实持续期[43]。然而,Meng等却发现高土壤水分含量缩短了群落开花持续期[33],这可能是因为不同植物的花期重叠导致植物对资源的竞争加剧,因为处在繁殖期的植物对资源的需求也较高[66]。尤其是缩短的群落开花持续期将会导致植物与传粉者之间的共生关系不匹配,进而影响植物的适合度[67]。利用遥感观测研究发现,群落物候初始期变化取决于生长季早期第一场雨的降临时间[68]。除降雨时间外,降雨量也会对物候期产生显著影响。例如,在青藏高原的许多区域降雨量增加能够显著提前返青期,尤其在高原干旱地区更明显[69]。但是也有研究发现了相反的趋势[68]。有人认为出现这些不同结论的原因可能是由计算降雨方法的差异造成的[70]。

雪融时间也是影响群落物候的重要因素。Lambert等[12]利用遥感方法发现,雪融时间每10 a提前4.1 d,则初花、盛花以及晚花期会相应地提前约3.2 d。类似地,Wang等[28]发现39.9%的高寒草甸和36.7%的高寒草原的植被返青期与雪融时间呈显著正相关。然而在阿尔卑斯山,因光周期的限制有些植物物候并没有追随雪融时间提前而提前[26],这可能是植物避免遭受霜害的生存策略[4]。

1.3 气候变化对根系物候的影响根系在生态系统能量和物质循环方面具有十分重要的作用[70-71],全球陆地生态系统的碳有很大比例储存在根系中[71]。所以,研究根系物候有助于更好地预测整个生态系统的生产力变化[72],并能够加深理解其对气候变化的响应[73]。本文所涉及的根系物候主要是指植物细根的物候变化,因为细根是根系系统中最具动态的部分[74]。

在高寒区域利用增温实验研究发现,增温显著提前了根系生长的初始期[75]。这说明土壤温度和根系生长之间存在显著的相关性[76]。而有些研究却认为光合产物有效性对根系物候的影响更大[77]。比如植物在秋季储存的养分(糖类化合物,尤其是淀粉)能够为下一年的生长提供物质基础[78],使其在早期生长中占据优势[73],这对休眠植物尤为重要[79]。也有人认为光通量密度(PPFD)对根系生长的影响较大,被认为是根系生长的最好预测者[80]。同时,不同物种的根系物候对气候变化的响应也存在差异。有些物种的根系物候对气候变化的响应保持相对稳定,而另一些物种的根系物候年际间变化差异较大[81]。例如,有些物种的根系在初夏具有较旺盛的生长能力,而其他物种的根系生长速率在整个生长季都保持相对稳定[82]。并且不同物种的根系获取土壤水分的能力也不同。例如,高寒区域的草本根系在生长季早期要比灌丛具有更高效的水分获取能力[83]。

除此之外,不同深度土壤中的根系生长对气候变化的响应也存在差异[73]。浅层根系可能要比深层根系更容易受土壤温度和水分的影响[84]。尤其对大部分根系生物量集中在地表的高寒植物而言[85],气候变暖导致的表层土壤干旱可能会限制根系的发育[76]。有研究发现浅层根系与地上物候保持较好的同步性,而深层土壤的根系生长却接近常数,可能与其能够获取稳定的深层水有关[72],因为这能够缓解季节性干旱带来的不利影响[86]。然而其他研究却认为根系物候变化较为多样,与地上部分物候变化并非同步[73, 87]。因为高寒区域地上部分通常在初春到秋末生长,而地下部分会在秋末甚至在冬季仍然生长[88]。所以,高寒区域地下根系物候的生长季长度可能要超过地上部分的50%左右[87]。这可能与它们的根系生长不受光周期约束[73]以及积雪覆盖起到保温作用有关[51],直接的证据是当移除积雪后,土壤结冰导致细根死亡[89]。地上和地下物候的这种不匹配或者分离可能是植物对养分分配所做出的权衡[87]。但也有研究认为有些物种的根系生长受光周期约束,比如禾本科植物根系会出现季节性生长终止现象[90]。这可能是因为这些物种的根系在土壤结冰前停止生长以便及时回收光合产物,从而减少呼吸消耗并为下一年生长储备养分。

1.4 物种组成对群落物候的影响群落与物种物候的变化并不匹配[91]。比如遥感和地面观测的结果表明增温延长群落水平的生长季长度,但很多物种水平的生长季长度却被缩短[91]。所以群落物候的变化可能是由不同物种或功能群的相互补偿造成的[3, 6, 68]。因此,有人认为群落物候的初花期提前主要是由早花植物驱动[92]。但气候变化背景下群落组成并非恒定,很多研究已经表明气候变化对群落物种或功能群组成产生显著的影响[19, 93]。比如短期增温降低早花植物的盖度、增加中花植物的盖度,而降温的效应与增温相反[94]。因此,群落中物种或功能群组成的变化可能会对群落物候产生显著的影响。Meng等[94]发现不同花期功能群植物的盖度变化与物候序列的变化存在显著的相关性,这说明温度的变化以及群落中不同植物花期功能群盖度的变化共同决定群落物候对气候变化的响应。群落中不同物种的响应差异以及物种组成的改变会重塑该生境的种间关系[95]。比如种间或种内的相互遮阴[54]、植物-传粉者不匹配[67]和植物-食草者采食压力改变[96]等。并且很多研究已表明这些变化可能会影响群落物候对气候变化的响应。

2 物候的温度敏感性植物物候的温度敏感性是指物候对温度变化的响应(或敏感)程度,研究植物物候温度敏感性可以预测植被在未来气候变化下的演变状态。通常采用物候变化率表示,在长期的物候观测中会用物候期与温度之间的斜率来表示(d·℃-1)[17];而在增温实验中通常采用温度每变化1 ℃物候期提前或延迟的天数来表示[7, 97]。但其变化程度可能随地理位置、植被类型、背景温度以及增温幅度等的不同而存在差异。

物候温度敏感性的预测是生态学中的一项重要挑战[17]。当前许多研究都认为高寒区域对温度变化的响应更敏感[6-7]。但高寒区域包含高纬度和高海拔等类型,然而当前对高海拔区域的研究相对较少,尤其是青藏高原[6-8]。同时,目前绝大多数物候研究只观测了少数物种,基于这些研究得出的结论可能会因物种间响应方向和幅度的差异而存在偏差,因为有研究发现不同的物种或功能群对气候变化的响应是不同的[6-7]。因此亟需对物候进行多物种的综合比较研究。在此,我们搜集了目前国际上物候研究的相关数据集,主要包括NECTAR (Network of Ecological and Climatological Timings Across Regions)、STONE (Synthesis of Timings Observed in iNcrease Experiments)以及PEP725(the Pan European Phenology Project, http://www.pep725.eu/)中的高纬度区域植物返青期或初花期;而高海拔地区的物候数据则从文献获取(表 1),主要包括青藏高原、洛基山等区域。对缺乏温度数据的区域,我们在GHCN (The Global Historical Climatology Network,http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/)中获取,并将这些物候数据按照上文中提到的两种计算方法统一转化为物候温度敏感性。我们试图通过整合分析了解两个不同区域类型的物候温度敏感性差异,虽然其他诸如水分、光周期等非生物因素也会对物候的温度敏感性产生影响,但温度是影响植物物候时间最长,且起主导作用的因子[17],所以在此只考虑温度对物候的影响,未来研究中应考虑多因素交互作用对物候的影响。

|

|

表 1 整合分析的部分数据来源 Table 1 Partial data resources of meta-analysis |

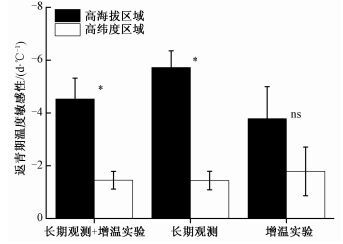

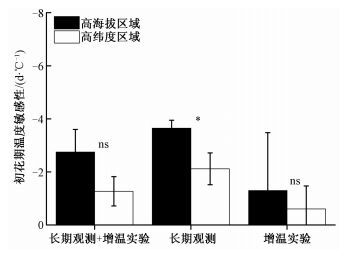

研究结果表明,高海拔区域长期观测、增温实验以及合并两种方法的数据后,它们返青期的温度敏感性分别为-5.72、-3.78和-4.53 d·℃-1,初花期的温度敏感性为-3.65、-1.30和-2.75 d·℃-1;而高纬度区域返青期温度敏感性分别为-1.44、-1.79和-1.45 d·℃-1,初花期的温度敏感性为-2.12、-0.61和-1.27 d·℃-1(图 1和图 2)。高海拔区域长期观测和合并二者数据的返青期温度敏感性以及长期观测的初花期温度敏感性都要显著高于高纬度区域,说明同为气候变化的敏感区,高海拔区域的物候变化要比高纬度区域更敏感。

|

Download:

|

|

*表示在0.05水平下的显著性差异, ns表示不存在显著性差异。 图 1 高海拔与高纬度区域植物返青期温度敏感性的比较 Fig. 1 Comparison of temperature sensitivity of green-up date between arctic and alpine regions |

|

|

Download:

|

|

*表示在0.05水平下的显著性差异, ns表示不存在显著性差异。 图 2 高海拔与高纬度区域植物初花期温度敏感性的比较 Fig. 2 Comparison of temperature sensitivity of first flowering date between arctic and alpine regions |

|

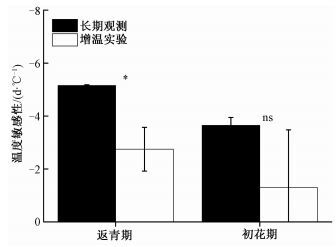

与以往研究相同[17],我们发现高海拔区域的增温实验显著低估了返青期的温度敏感性(图 3),这可能是因为增温导致的土壤干旱限制植物返青提前[17],尤其对受夏季风影响的青藏高原更是如此[102]。初花期温度敏感性的两种研究方法却没有显著差异(图 3),可能是因为温度变化幅度还没达到影响初花期非线性响应的阈值,而在阈值前追随温度变化保持线性响应[57]。

|

Download:

|

|

*表示在0.05水平下的显著性差异, ns表示不存在显著性差异。 图 3 高海拔区域长期观测与增温实验两种方法获得的返青期和初花期温度敏感性比较 Fig. 3 Comparison of temperature sensitivities of green-up date and initial time of flowering between long-term observations and warming experiments |

|

植物物候在生产、生态以及气候变化等方面都具有十分重要的意义,特别是作为气候变化的敏感指标之一,已经受到越来越多的关注。根据上述研究现状,我们从以下3个方面进行总结,并提出需要进一步研究的科学问题。

1) 气候变化对地上物候的影响

总体而言,多数研究表明增温和积雪早融均能使植物个体和群落的返青期和初花期提前,枯黄期延迟;但降水模式变化的影响却没有一致的结论。其中,由于研究方法、地点以及研究对象等的差异,使得温度和降水等因素对植物物候影响的研究结果存在很大的不确定性。因此,未来气候变化情景下,如何预测温度以及水分变化对植物物候的影响仍然是一个极为重要的问题。尤其是以上研究多针对单个物候期的变化,很少考虑前一个物候如何影响后序物候变化的方向和程度。同时,相对于物候初始期,对物候持续期的研究更少。尤其值得注意的是,以上长时间序列的物候分析都掩盖掉了大量的信息,比如无法区分增温和降温对物候的相对影响。深入理解植物对增温和降温响应的非对称性和非线性,有助于更准确地预测植物物候的变化。因此,未来的物候研究应将长期的地面观测和合理设计的控制实验相结合,如开展不同幅度的增温实验等。

植物个体对气候变化响应的差异会改变群落结构,而群落结构的改变又反过来影响群落物候对气候变化的响应。所以,气候变化会通过改变群落中的物种组成间接影响群落物候的响应。但到目前为止,很少有研究关注物种组成如何修饰群落物候对温度变化的响应,在以遥感作为主要方法的物候研究中表现得更为突出,因为遥感无法监测到群落内物种的变化。

迄今为止,大多数生态学研究关注环境因子(主要为温度和水分)对植物物候的影响,但对植物本身的生物学变化机理研究极少。未来的物候研究应将野外定位观测与室内分子生物学技术结合起来,从机理上阐明植物物候对气候变化的响应策略。

2) 气候变化对根系物候的影响

很少有气候变化对根系物候影响的研究报道,在所有5次IPCC报告中也均未涉及[73]。当前少数研究发现土壤温度、水分以及养分有效性等都会对根系物候产生重要的影响。但因研究较少,还没有一致的结论。同时,对根系物候与地上部分同步性的了解也较缺乏。因此,为了更好地理解群落的生态和生物地球化学过程以及气候变化对它们的影响,应借助有效的技术(如微根管法等)加强对根系物候的研究。

3) 物候的温度敏感性

高寒区域作为气候变化的敏感区,对气候变化的响应尤其显著。然而我们的整合分析结果表明同为气候变化敏感区,高海拔区域的物候温度敏感性要比高纬度区域更敏感。但是相对于高纬度区域,高海拔区域的物候研究相对较少,尤其是青藏高原。同时,因影响因子众多,目前对温度敏感性的响应机制仍然不明确,未来还需要深入的研究。

| [1] | Lieth H. Phenology and seasonality modeling[M]. New York: Springer Science and Business Media, 2013: 4-19. |

| [2] | Walther G R, Post E, Convey P, et al. Ecological responses to recent climate change[J]. Nature, 2002, 416(6879):389–395. DOI:10.1038/416389a |

| [3] | Cleland E E, Chuine I, Menzel A, et al. Shifting plant phenology in response to global change[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2007, 22(7):357–365. |

| [4] | Richardson A D, Keenan T F, Migliavacca M, et al. Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system[J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2013, 169(2013):156–173. |

| [5] | Kathuroju N, White M A, Symanzik J, et al. On the use of the advanced very high resolution radiometer for development of prognostic land surface phenology models[J]. Ecological Modelling, 2007, 201(2):144–156. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.09.011 |

| [6] | Wang S, Wang C, Duan J, et al. Timing and duration of phenological sequences of alpine plants along an elevation gradient on the Tibetan plateau[J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2014, 189/190(2014):220–228. |

| [7] | Wang S, Meng F, Duan J, et al. Asymmetric sensitivity of first flowering date to warming and cooling in alpine plants[J]. Ecology, 2014, 95(12):3387–3398. DOI:10.1890/13-2235.1 |

| [8] | Dorji T, Totland O, Moe S R, et al. Plant functional traits mediate reproductive phenology and success in response to experimental warming and snow addition in Tibet[J]. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(2):459–472. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2012.19.issue-2 |

| [9] | Piao S, Cui M, Chen A, et al. Altitude and temperature dependence of change in the spring vegetation green-up date from 1982 to 2006 in the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau[J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2011, 151(12):1599–1608. DOI:10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.06.016 |

| [10] | Jeong S, Ho C, Gim H, et al. Phenology shifts at start vs. end of growing season in temperate vegetation over the Northern Hemisphere for the period 1982-2008[J]. Global Change Biology, 2011, 17(7):2385–2399. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02397.x |

| [11] | Chuine I, Yiou P, Viovy N, et al. Historical phenology: grape ripening as a past climate indicator[J]. Nature, 2004, 432(7015):289–290. DOI:10.1038/432289a |

| [12] | Lambert A M, Miller-Rushing A J, Inouye D W. Changes in snowmelt date and summer precipitation affect the flowering phenology of Erythronium grandiflorum (glacier lily; liliaceae)[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2010, 97(9):1431–1437. DOI:10.3732/ajb.1000095 |

| [13] | Hansen J, Sato M, Ruedy R, et al. Global temperature change[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2006, 103(39):14288–14293. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0606291103 |

| [14] | Houghton J T, Ding Y, Griggs D J, et al. Climate Change 2001: The scientific basis[M]. Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of Cambridge University, 2001: 156-159. |

| [15] | Thomas C D, Cameron A, Green R E, et al. Extinction risk from climate change[J]. Nature, 2004, 427(6970):145–148. DOI:10.1038/nature02121 |

| [16] | Inouye D W, Wielgolaski F E. Phenology at High Altitudes [C]//Schwartz M D. Phenology: An integrative environmental science. London, UK: Kluwer Academic, 2013: 249-272. |

| [17] | Wolkovich E M, Cook B I, Allen J M, et al. Warming experiments underpredict plant phenological responses to climate change[J]. Nature, 2012, 485(7399):494–497. |

| [18] | Ibanez I, Primack R B, Miller-Rushing A J, et al. Forecasting phenology under global warming[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2010, 365(1555):3247–3260. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2010.0120 |

| [19] | Walker M D, Wahren C H, Hollister R D, et al. Plant community responses to experimental warming across the tundra biome[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2006, 103(5):1342–1346. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0503198103 |

| [20] | Forrest J, Inouye D W, Thomson J D. Flowering phenology in subalpine meadows: Does climate variation influence community co-flowering patterns?[J]. Ecology, 2010, 91(2):431–440. DOI:10.1890/09-0099.1 |

| [21] | Bliss L. Adaptations of arctic and alpine plants to environmental conditions[J]. Arctic, 1962, 15(2):117–144. |

| [22] | Tieszen L L, Lewis M C, Miller P C, et al. An analysis of processes of primary production in tundra growth forms [C]//Bliss L C, Heal O W, Moore J J. Tundra ecosystems: a comparative analysis. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1981: 285-356. |

| [23] | Pieper S J, Loewen V, Gill M, et al. Plant responses to natural and experimental variations in temperature in alpine tundra, southern Yukon, Canada[J]. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 2011, 43(3):442–456. DOI:10.1657/1938-4246-43.3.442 |

| [24] | 葛全胜, 戴君虎, 郑景云. 物候学研究进展及中国现代物候学面临的挑战[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2010, 25(3):310–316. |

| [25] | Wielgolaski F E, Inouye D W. Phenology at High Latitudes [C]//Schwartz M D. Phenology: an integrative environmental science. London, UK: Kluwer Academic, 2013: 225-247. |

| [26] | Keller F, Körner C. The role of photoperiodism in alpine plant development[J]. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 2003, 35(3):361–368. DOI:10.1657/1523-0430(2003)035[0361:TROPIA]2.0.CO;2 |

| [27] | Jiang L, Wang S, Meng F, et al. Relatively stable response of fruiting stage to warming and cooling relative to other phenological events[J]. Ecology, 2016, 97(8):1961–1969. DOI:10.1002/ecy.1450 |

| [28] | Wang K, Zhang L, Qiu Y, et al. Snow effects on alpine vegetation in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau[J]. International Journal of Digital Earth, 2015, 8(1):56–73. |

| [29] | Arft A M, Walker M D, Gurevitch J, et al. Responses of tundra plants to experimental warming: meta-analysis of the international tundra experiment[J]. Ecological Monographs, 1999, 69(4):491–511. |

| [30] | Delbart N, Picard G. Modeling the date of leaf appearance in low-arctic tundra[J]. Global Change Biology, 2007, 13(12):2551–2562. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2007.13.issue-12 |

| [31] | Miller-Rushing A J, Primack R B. Global warming and flowering times in Thoreau's Concord: a community perspective[J]. Ecology, 2008, 89(2):332–341. DOI:10.1890/07-0068.1 |

| [32] | Sherry R A, Zhou X, Gu S, et al. Divergence of reproductive phenology under climate warming[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2007, 104(1):198–202. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0605642104 |

| [33] | Meng F, Cui S, Wang S, et al. Changes in phenological sequences of alpine communities across a natural elevation gradient[J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2016, 224(2016):11–16. |

| [34] | Defila C, Clot B. Phytophenological trends in the Swiss Alps, 1951-2002[J]. Meteorologische Zeitschrift, 2005, 14(2):191–196. DOI:10.1127/0941-2948/2005/0021 |

| [35] | Xu Z, Hu T, Wang K, et al. Short-term responses of phenology, shoot growth and leaf traits of four alpine shrubs in a timberline ecotone to simulated global warming, Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China[J]. Plant Species Biology, 2009, 24(1):27–34. DOI:10.1111/psb.2009.24.issue-1 |

| [36] | Hart R, Salick J, Ranjitkar S, et al. Herbarium specimens show contrasting phenological responses to Himalayan climate[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2014, 111(29):10615–10619. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1403376111 |

| [37] | Cook B I, Wolkovich E M, Parmesan C. Divergent responses to spring and winter warming drive community level flowering trends[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2012, 109(23):9000–9005. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1118364109 |

| [38] | Post E S, Pedersen C, Wilmers C C, et al. Phenological sequences reveal aggregate life history response to climatic warming[J]. Ecology, 2008, 89(2):363–370. DOI:10.1890/06-2138.1 |

| [39] | CaraDonna P J, Iler A M, Inouye D W. Shifts in flowering phenology reshape a subalpine plant community[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2014, 111(13):4916–4921. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1323073111 |

| [40] | Stearns S C. The evolution of life histories[M]. Davies, CA, USA: Oxford University Press Oxford, 1992: 230-250. |

| [41] | Taeger S, Sparks T H, Menzel A. Effects of temperature and drought manipulations on seedlings of Scots pine provenances[J]. Plant biology (Stuttgart, Germany), 2015, 17(2):361–372. DOI:10.1111/plb.12245 |

| [42] | Peñuelas J, Filella I, Zhang X, et al. Complex spatiotemporal phenological shifts as a response to rainfall changes[J]. New Phytologist, 2004, 161(3):837–846. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01003.x |

| [43] | Galen C. Why do flowers vary?[J]. Bioscience, 1999, 49(8):631. DOI:10.2307/1313439 |

| [44] | 吕新苗, 康世昌, 朱立平, 等. 西藏纳木错植物物候及其对气候的响应[J]. 山地学报, 2009, 27(6):648–654. |

| [45] | Reyes-Fox M, Steltzer H, Trlica M J, et al. Elevated CO2 further lengthens growing season under warming conditions[J]. Nature, 2014, 510(7504):259–262. DOI:10.1038/nature13207 |

| [46] | White A, Cannell M G, Friend A D. Climate change impacts on ecosystems and the terrestrial carbon sink: a new assessment[J]. Global environmental change, 1999, 9(1999). |

| [47] | Beniston M, Diaz H, Bradley R. Climatic change at high elevation sites: an overview[J]. Climatic Change, 1997, 36(3/4):233–251. DOI:10.1023/A:1005380714349 |

| [48] | Yu Z, Liu S, Wang J, et al. Effects of seasonal snow on the growing season of temperate vegetation in China[J]. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(7):2182–2195. DOI:10.1111/gcb.12206 |

| [49] | Odland A. Estimation of the growing season length in alpine areas: effects of snow and temperatures [C]//Scmidt J G. Alpine environment: geology, ecology and conservation. New York: Nova Science Publication, 2011: 1-50. |

| [50] | Woodley E J, Svoboda J. Effects of habitat on variations of phenology and nutrient concentration among four common plant species of the Alexandra Fiord Lowland [C]//Svoboda J, Freedman B. Ecology of a polar oasis, Alexandra Fiord, Ellesmere Island, Canada. Toronto: Captus University Press, 1994: 157-175. |

| [51] | Nobrega S, Grogan P. Deeper snow enhances winter respiration from both plant-associated and bulk soil carbon pools in birch hummock tundra[J]. Ecosystems, 2007, 10(3):419–431. DOI:10.1007/s10021-007-9033-z |

| [52] | Shutova E, Wielgolaski F E, Karlsen S R, et al. Growing seasons of Nordic mountain birch in northernmost Europe as indicated by long-term field studies and analyses of satellite images[J]. International Journal of Biometeorology, 2006, 51(2):155–166. DOI:10.1007/s00484-006-0042-y |

| [53] | Larcher W. Klimastreβ im Gebirge: adaptation straining und Selektionsfilter für Pflanzen. Florengeschichte im Spiegel blütenökologischer Erkenntnisse[M]. German: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1980: 49-80. |

| [54] | Körner C. Alpine plant life: Functional plant ecology of high mountain ecosystems[M]. New York, USA: Springer Science & Business Media, 2003: 40-41. |

| [55] | Stinson K A. Natural selection favors rapid reproductive phenology in Potentilla pulcherrima (Rosaceae) at opposite ends of a subalpine snowmelt gradient[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2004, 91(4):531–539. DOI:10.3732/ajb.91.4.531 |

| [56] | Ernakovich J G, Hopping K A, Berdanier A B, et al. Predicted responses of arctic and alpine ecosystems to altered seasonality under climate change[J]. Global Change Biology, 2014, 20(10):3256–3269. DOI:10.1111/gcb.12568 |

| [57] | Meng F, Zhou Y, Wang S, et al. Temperature sensitivity thresholds to warming and cooling in phenophases of alpine plants[J]. Climatic Change, 2016, 239(2016):579–590. |

| [58] | Yu H, Luedeling E, Xu J. Winter and spring warming result in delayed spring phenology on the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2010, 107(51):22151–22156. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1012490107 |

| [59] | Shen M, Sun Z, Wang S, et al. No evidence of continuously advanced green-up dates in the Tibetan Plateau over the last decade[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2013, 110(26):E2329. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1304625110 |

| [60] | Yi S, Zhou Z. Increasing contamination might have delayed spring phenology on the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2011, 108(19):E94–E94. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1100394108 |

| [61] | Chen H, Zhu Q, Wu N, et al. Delayed spring phenology on the Tibetan Plateau may also be attributable to other factors than winter and spring warming[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2011, 108(19):E93. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1100091108 |

| [62] | Marchand F L, Nijs I, Heuer M, et al. Climate warming postpones senescence in High Arctic tundra[J]. Arctic Antarctic and Alpine Research, 2004, 36(4):390–394. DOI:10.1657/1523-0430(2004)036[0390:CWPSIH]2.0.CO;2 |

| [63] | Zavaleta E S, Thomas B D, Chiariello N R, et al. Plants reverse warming effect on ecosystem water balance[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2003, 100(17):9892–9893. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1732012100 |

| [64] | Morin X, Roy J, Sonie L, et al. Changes in leaf phenology of three European oak species in response to experimental climate change[J]. New Phytologist, 2010, 186(4):900–910. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03252.x |

| [65] | Craine J M, Wolkovich E M, Towne E G, et al. Flowering phenology as a functional trait in a tallgrass prairie[J]. New Phytologist, 2012, 193(3):673–682. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03953.x |

| [66] | Kliber A, Eckert C G. Sequential decline in allocation among flowers within inflorescences: Proximate mechanisms and adaptive significance[J]. Ecology, 2004, 85(6):1675–1687. DOI:10.1890/03-0477 |

| [67] | Memmott J, Craze P G, Waser N M, et al. Global warming and the disruption of plant-pollinator interactions[J]. Ecology Letters, 2007, 10(8):710–717. DOI:10.1111/ele.2007.10.issue-8 |

| [68] | Cleland E E, Chiariello N R, Loarie S R, et al. Diverse responses of phenology to global changes in a grassland ecosystem[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2006, 103(37):13740–13744. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0600815103 |

| [69] | 裴顺祥, 郭泉水, 辛学兵, 等. 国外植物物候对气候变化响应的研究进展[J]. 世界林业研究, 2009, 22(6):31–37. |

| [70] | Shen M, Tang Y, Chen J, et al. Influences of temperature and precipitation before the growing season on spring phenology in grasslands of the central and eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau[J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2011, 151(12):1711–1722. DOI:10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.07.003 |

| [71] | Robinson D. Implications of a large global root biomass for carbon sink estimates and for soil carbon dynamics[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological, Sciences, 2007, 274(1626):2753–2759. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2007.1012 |

| [72] | Brouwer R. Functional equilibrium: sense or nonsense[J]. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science, 1983, 31(4):335–348. |

| [73] | Radville L, McCormack M L, Post E, et al. Root phenology in a changing climate[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2016, 67(12):3617–3628. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erw062 |

| [74] | Blume-Werry G, Wilson S D, Kreyling J, et al. The hidden season: growing season is 50% longer below than above ground along an arctic elevation gradient[J]. New Phytologist, 2016, 209(3):978–986. DOI:10.1111/nph.13655 |

| [75] | Sullivan P F, Welker J M. Warming chambers stimulate early season growth of an arctic sedge: Results of a minirhizotron field study[J]. Oecologia, 2005, 142(4):616–626. DOI:10.1007/s00442-004-1764-3 |

| [76] | Steinaker D F, Wilson S D, Peltzer D A. Asynchronicity in root and shoot phenology in grasses and woody plants[J]. Global Change Biology, 2010, 16(8):2241–2251. |

| [77] | Tierney G L, Fahey T J, Groffman P M, et al. Environmental control of fine root dynamics in a northern hardwood forest[J]. Global Change Biology, 2003, 9(5):670–679. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00622.x |

| [78] | Najar A, Landhausser S M, Whitehill J G, et al. Reserves accumulated in non-photosynthetic organs during the previous growing season drive plant defenses and growth in aspen in the subsequent growing season[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2014, 40(1):21–30. DOI:10.1007/s10886-013-0374-0 |

| [79] | Kummerow J, Russell M. Seasonal root-growth in the Arctic tussock tundra[J]. Oecologia, 1980, 47(2):196–199. DOI:10.1007/BF00346820 |

| [80] | Edwards E J, Benham D G, Marland L A, et al. Root production is determined by radiation flux in a temperate grassland community[J]. Global Change Biology, 2004, 10(2):209–227. DOI:10.1111/gcb.2004.10.issue-2 |

| [81] | McCormack M L, Adams T S, Smithwick E A H, et al. Variability in root production, phenology, and turnover rate among 12 temperate tree species[J]. Ecology, 2014, 95(8):2224–2235. DOI:10.1890/13-1942.1 |

| [82] | Romberger J A, Mikola P. International Review of Forestry Research[M]. New York & London: Academic press, 1967: 181-206. |

| [83] | Eissenstat D M, Caldwell M M. Competitive ability is linked to rates of water extraction: a field study of 2 aridland tussock grasses[J]. Oecologia, 1988, 75(1):1–7. DOI:10.1007/BF00378806 |

| [84] | Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. The relationship between fine root demography and the soil environment in northern hardwood forests[J]. Ecoscience, 1997, 4(1):99–105. DOI:10.1080/11956860.1997.11682383 |

| [85] | 龙毅, 孟凡栋, 王常顺, 等. 高寒草甸主要植物地上地下生物量分布及退化对根冠比和根系表面积的影响[J]. 广西植物, 2015, 35(4):532–538. DOI:10.11931/guihaia.gxzw201406032 |

| [86] | Hendrick R L, Pregitzer K S. Temporal and depth-related patterns of fine root dynamics in northern hardwood forests[J]. Journal of Ecology, 1996, 84(2):167–176. DOI:10.2307/2261352 |

| [87] | Blume-Werry G, Wilson S D, Kreyling J, et al. The hidden season: growing season is 50% longer below than above ground along an arctic elevation gradient[J]. New Phytologist, 2016, 209(3):978–986. DOI:10.1111/nph.13655 |

| [88] | Onipchenko V G, Makarov M I, van Logtestijn R S, et al. New nitrogen uptake strategy: specialized snow roots[J]. Ecology Letters, 2009, 12(8):758–764. DOI:10.1111/ele.2009.12.issue-8 |

| [89] | Tierney G L, Fahey T J, Groffman P M, et al. Soil freezing alters fine root dynamics in a northern hardwood forest[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2001, 56(2):175–190. DOI:10.1023/A:1013072519889 |

| [90] | Shaver G R, Billings W D. Effects of daylength and temperature on root elongation in tundra-graminoids[J]. Oecologia, 1977, 28(1):57–65. DOI:10.1007/BF00346836 |

| [91] | Steltzer H, Post E. Seasons and life cycles[J]. Science, 2009, 324(5929):886–887. DOI:10.1126/science.1171542 |

| [92] | Xia J, Wan S. Independent effects of warming and nitrogen addition on plant phenology in the Inner Mongolian steppe[J]. Annals of Botany, 2013, 111(6):1207–1217. DOI:10.1093/aob/mct079 |

| [93] | Wang S, Duan J, Xu G, et al. Effects of warming and grazing on soil N availability, species composition, and ANPP in an alpine meadow[J]. Ecology, 2012, 93(11):2365–2376. DOI:10.1890/11-1408.1 |

| [94] | Meng F, Jiang L, Zhang Z, et al. , Changes in flowering functional group affect responses of community phenological sequences to temperature change[J]. Ecology, 2016. DOI:10.1002/ecy.1685 |

| [95] | Tang J, Körner C, Muraoka H, et al. Emerging opportunities and challenges in phenology: a review[J]. Ecosphere, 2016. DOI:10.1002/ecs2.1436 |

| [96] | Fenner M. The phenology of growth and reproduction in plants: perspectives in plant ecology[J]. Evolution and Systematics, 1998, 1(1):78–91. |

| [97] | Rutishauser T, Stockli R, Harte J, et al. Climate change: flowering in the greenhouse[J]. Nature, 2012, 485(7399):448–449. DOI:10.1038/485448a |

| [98] | 王力, 李凤霞, 周万福, 等. 气候变化对不同海拔高山嵩草物候期的影响[J]. 草业科学, 2012, 29(8):1256–1261. |

| [99] | Diez J M, Ibanez I, Miller-Rushing A J, et al. Forecasting phenology: from species variability to community patterns[J]. Ecology Letters, 2012, 15(6):545–553. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01765.x |

| [100] | Iler A M, Hoye T T, Inouye D W, et al. Nonlinear flowering responses to climate: Are species approaching their limits of phenological change?[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 2013, 368(1624):20120489. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2012.0489 |

| [101] | Cornelius C, Estrella N, Franz H, et al. Linking altitudinal gradients and temperature responses of plant phenology in the Bavarian Alps[J]. Plant Biology, 2013, 15(2013):57–69. |

| [102] | Ganjurjav H, Gao Q, Schwartz M W, et al. Complex responses of spring vegetation growth to climate in a moisture-limited alpine meadow[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6:23356. DOI:10.1038/srep23356 |

2017, Vol. 34

2017, Vol. 34