锌是维持人体健康的必需微量元素,参与300多种酶、RNA、DNA和蛋白质的合成,对维持细胞膜稳定性和骨骼系统正常发育、发挥免疫功能和抗氧化作用至关重要[1 – 4]。锌主要通过膳食摄入进入人体。人体锌不足或缺乏非常普遍。流行病学数据显示,全球至少20 %的人有锌缺乏风险[5]。严重锌缺乏可导致死亡。据估计,在全球总人口死亡原因中锌缺乏占1 %,在全球6个月至5岁儿童死亡原因中占4.4 %[6]。锌也是维持胎儿生长发育所需的重要营养素。与非孕期相比,孕期妇女每天应多补充2~4 mg的锌[7]。锌以主动转运形式通过胎盘进入胎儿循环。与母亲体循环相比,脐带血锌浓度更高[8],并与母体血锌浓度成正比[9]。母体锌水平下降可能引起功能性锌缺乏症。当锌缺乏症发生于胚胎发育的器官生成关键期时,可能产生致畸效应,导致出生缺陷[10]。先天性心脏病(congenital heart diseases,CHDs)、唇腭裂(orofacial clefts,OFCs)和神经管缺陷(neural tube defects,NTDs)是最常见的3种重大出生缺陷。根据中国2011年以医院为基础的出生缺陷监测数据,CHDs、OFCs和NTDs围产期患病率分别居第1、第3和第8位[11]。CHDs、OFCs和NTDs可由遗传、环境因素或基因 – 环境交互作用引起。孕期母亲营养状况是重要的环境因素之一,营养素不足或过量,对母亲或子代都会产生不良影响 [7]。大量研究表明,孕期母体锌不足或缺乏可能与胎儿CHDs、OFCs和NTDs的发生存在关联。

1 锌与CHDs锌缺乏对心脏发育的致畸作用已在动物实验中得到证明。大鼠不同锌含量饲料饲养25 d后交配,孕后继续给予该饲料,结果发现中等程度以上的低锌增加胎鼠心脏畸形的发生,且其作用具有较明显的剂量 – 效应关系 [12]。大鼠孕第0天开始,每天经口灌入按体重计算等量的蒸馏水或30 mg/kg锌,孕第8~9天腹腔注射1 mL 8 μmol/L同型半胱氨酸(homocysteine,HCY),结果发现锌 + HCY组胎鼠心脏畸形发生率远低于单纯HCY注射组,提示锌能有效降低HCY对胎鼠心脏发育的致畸作用[13]。

早在1976年,Jameson等[14]报道,与生育正常子代的母亲相比,发生不良妊娠结局母亲孕早期的血清锌浓度普遍较低;生育CHDs患儿的母亲更为明显,孕第13周时,血清锌浓度最低。目前,针对孕期母体锌水平与子代CHDs发生关系的研究主要来自于国内。2007 — 2012年间在山西省进行的一项病例对照研究显示,母亲孕早期增补锌及含锌制剂对子代CHDs具有保护作用(OR = 0.493,95 % CI = 0.273~0.890)[15]。对母亲全血锌浓度检测发现,生育CHDs患儿母亲全血锌浓度低于对照组,提示孕期母体全血锌水平低可能增加子代CHDs的发病风险[16]。然而,发锌浓度检测发现,生育CHDs患儿母亲与对照组并无统计学差异[17]。需要注意的是,在该研究中进行发锌浓度测量时,并没有根据头发生长速度检测孕早期生长的那段头发,结果未必能准确反映孕期母体、特别是孕早期母体体内锌水平。

基于以上研究,有部分证据表明孕期母体锌不足或缺乏可能是子代CHDs的危险因素之一。但需要更多人群研究证据来证明孕期母体锌水平与CHDs之间的因果关系。

2 锌与OFCsOFCs是最常见的颌面部畸形,一般分为唇裂(Cleft lip,CL)、腭裂(cleft palate,CP)和唇裂合并腭裂(cleft lip with cleft palate,CLP)3种类型。动物实验表明,锌对胎鼠腭发育具有保护作用。大鼠孕第11~15天,每天分别皮下注射依地酸钙(calcium edetate,CaEDTA)或含锌依地酸钙(ZnCaEDTA)2次,结果发现含锌组胎鼠均发育正常,而CaEDTA组胎鼠发生CP等先天畸形,提示锌可以有效干预CaEDTA对胎鼠腭发育的致畸作用[18]。给予孕鼠锌缺乏性纯化饲料,同时严格消除环境锌污染,可诱发胎鼠CP[19]。给予Wistar孕鼠无锌纯化饲料,也可诱发胎鼠CP[20 – 21]。

荷兰的一项病例对照研究显示,CLP患儿及其母亲静脉血锌浓度均低于对照组;母亲红细胞锌浓度 < 189 μmol/L者,生育CLP患儿的风险增加1倍;子代红细胞锌浓度 < 118 μmol/L时,CLP的发病风险增加2.3倍 [22]。对母亲血浆锌浓度检测发现,锌浓度 > 9.0 μmol/L者,生育OFCs患儿的风险降低,且呈剂量 – 反应关系 [23]。母亲全血、血清锌浓度检测分析同样支持上述结论[24 – 25]。人群膳食调查结果显示,孕期锌摄入量低,母亲生育CP患儿的风险至少增加1倍[26]。对OFCs家庭膳食营养状况调查分析发现,OFCs家庭锌等营养物质摄入量明显不足,远低于中国营养学会每日营养素供给量标准和对照家庭[27]。但是,美国一项大型的病例对照研究结果显示,生育OFCs患儿母亲和对照母亲平均血浆锌浓度差异无统计学意义[28];比较生育OFCs患儿母亲和健康儿童母亲的指甲锌浓度,也认为孕期母体锌水平与子代OFCs发生风险无关[29]。

虽然目前孕期母体锌水平与OFCs发生关系尚有争议,但根据已有的动物研究和流行病学证据,认为孕期母体锌不足或缺乏很可能是子代OFCs发生的一个重要环境危险因素。

3 锌与NTDsNTDs主要包括无脑畸形、脊柱裂和脑膨出3种类型。动物实验发现,小鼠锌缺乏可以引起胎鼠中枢神经系统畸形[20, 30]。随后,多项人群研究发现,孕期母体锌不足或缺乏与子代NTDs发生存在关联。土耳其研究发现,生育NTDs患儿母亲的血清、血浆、红细胞和头发锌浓度均低于对照组[31 – 34]。Velie等[35]对生育NTDs患儿母亲和健康儿童母亲的孕前饮食情况进行问卷调查,结果发现,孕前锌摄入量高与子代NTDs风险低存在关联(OR = 0.65,95 % CI = 0.43~0.99)。母亲红细胞锌浓度 < 190 μmol/L,生育脊柱裂患儿的风险增加4.3倍 [36]。针对矿物质开采污染区的人群调查发现,NTDs患儿血清锌浓度低于对照组,且29 %的NTDs患儿患有锌缺乏症[37]。检测孕中期因诊断胎儿NTDs而终止妊娠母亲的血清锌浓度,结果发现病例组血清锌浓度[(62.48 ± 15.9)μg/dL]远低于对照组[(102.6 ± 23.7)μg/dL][38],提示孕期母体锌水平与子代NTDs发生可能有关。我国山西省和河北省是出生缺陷高发地区,本课题组2003 — 2007年在这两省的10个高发市、县共收集452份母亲头发(191例生育NTDs患儿病例和261例健康对照),根据头发生长速度,检测围受孕期头发锌浓度,结果表明发锌浓度 > 169 ng/mg的母亲,生育脊柱裂患儿的风险降低 [39]。我国其他地区的研究也提示孕期母体锌不足或缺乏与子代NTDs发生可能有关[40 – 41]。

基于上述研究,可以认为孕期母体锌不足或缺乏与子代NTDs的发生有关,锌水平低是母亲生育NTDs患儿的危险因素。

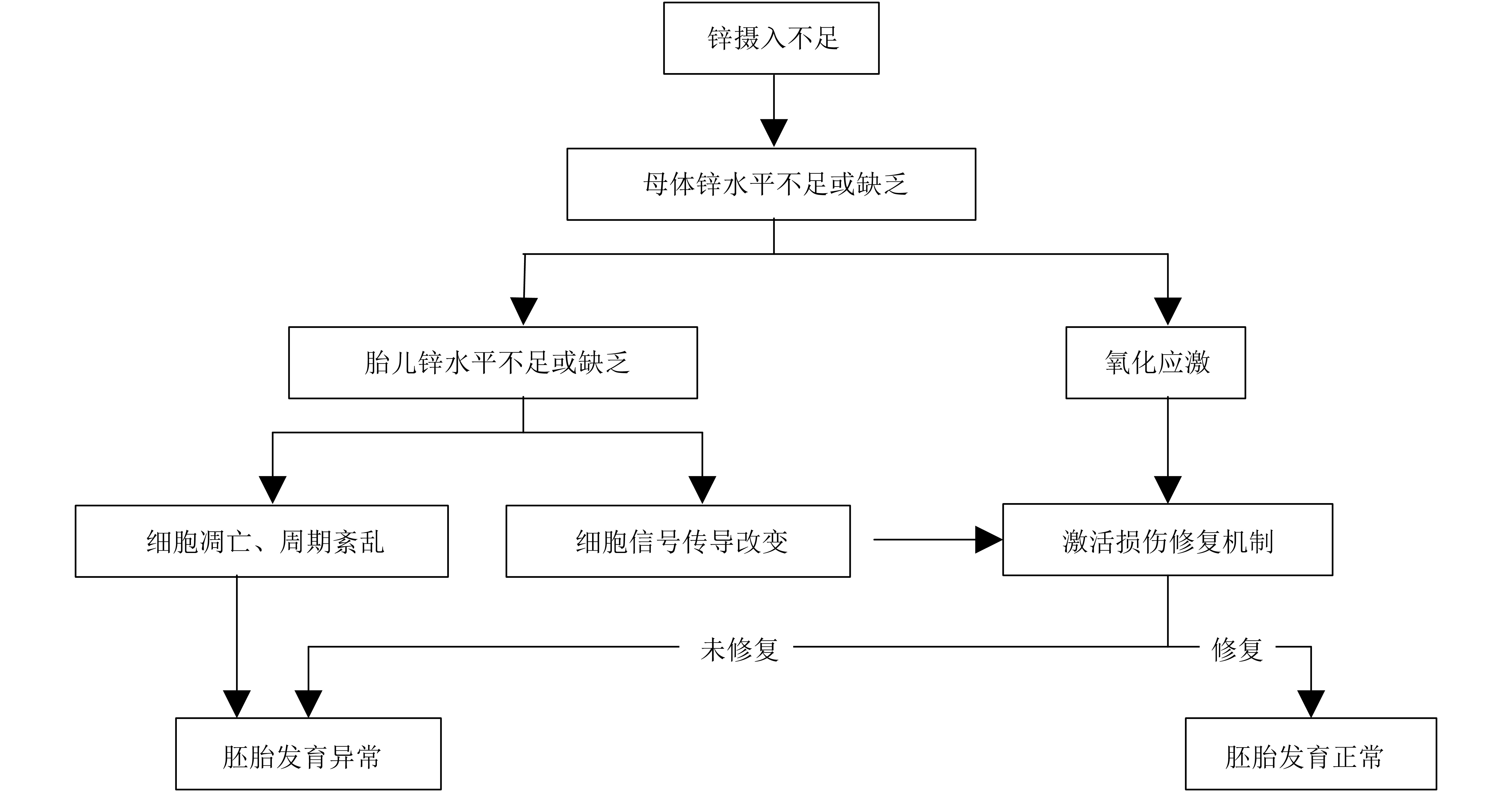

4 锌不足或缺乏致畸的可能机制细胞增殖、分化、迁移和凋亡程序的密切协调,以及细胞信号传导正常是胎儿组织器官正常发育的基础。胚胎早期对氧化应激敏感度高,组织抗氧化能力较弱,容易受氧化应激损伤,诱发胚胎缺陷。根据已有的研究,锌不足或缺乏对胎儿致畸作用主要可能与细胞凋亡和细胞周期紊乱、氧化应激和损伤、细胞信号传导改变有关,可能机制如图1所示。

|

图 1 锌不足或缺乏致畸作用的可能机制示意图 |

4.1 细胞凋亡和细胞周期紊乱

目前已证实凋亡与畸形发生密切相关,而锌缺乏可以促进胚胎细胞凋亡。孕鼠锌缺乏,胚胎神经管、咽弓和体节等部位细胞凋亡均增加[42 – 43]。神经嵴细胞对锌缺乏性不良影响尤为敏感。有研究推测,锌缺乏引起神经嵴细胞代谢或神经嵴细胞迁移模式改变是胎儿心脏发育异常的基础[44]。神经嵴细胞的正常迁移也是神经管和唇腭发育的基础。虽然胚胎早期细胞周期动力学仍不明确,但在低锌培养环境下,G0/G1期的细胞停滞生长,且分裂到S期的细胞减少[45 – 46]。锌缺乏,细胞凋亡增加、周期紊乱,胚胎的正常发育受到影响。

4.2 氧化应激锌参与机体多层抗氧化防御系统的构成,如铜锌超氧化物歧化酶、金属结合蛋白MT等。锌缺乏,多种类型细胞中的活性氧和活性氮升高,引起一氧化氮合酶活性增加、还原型辅酶Ⅱ活化[47 – 48];脂质、蛋白质[49 – 50]和DNA [51 – 52]氧化损伤。此时,母体处于一种高氧化应激状态,对胚胎发育有不良影响。

4.3 细胞信号传导改变锌与多种蛋白、转录因子结合,组成锌结合蛋白或锌指转录因子,参与细胞信号传导。锌缺乏,锌指转录因子中的半胱氨酸氧化,活性下降[53];锌指转录因子GATA-4的DNA结合活性改变,α–肌球蛋白重链和心脏肌钙蛋白–I表达下调[54];细胞内活化T细胞核转录因子(nuclear factor of activated T-cells,NFAT)活性升高,细胞微管退化,NFAT依懒性基因转录下调[53];锌依赖性因子Shh的信号传导改变[55]。其中,α–肌球蛋白重链和心脏肌钙蛋白–I是早期心脏发育的关键基因;NFAT与心脏、神经元、肌肉等发育有关;Shh参与众多器官或组织发育的信号调节。信号转导的异常改变,与神经管和心脏等的发育异常有关。

5 小 结基于已有研究证据,孕期母体锌不足或缺乏可能是CHDs、OFCs和NTDs三种重大结构缺陷的危险因素。但由于目前的研究大多是病例对照设计,所发现的锌水平低与出生缺陷风险高之间的关联,尚不能认为是因果关系。这就需要通过建立孕早期研究队列,来检验母亲孕早期体内锌水平与子代出生缺陷风险之间的因果关系。另外,何种生物标本内的锌含量能够反映母体锌水平尚不清楚,已有研究所使用的生物标本包括血清、血浆、红细胞、全血、头发、指甲等。鉴于血清或血浆是临床最常用的生物标本,因此,使用血清、血浆、全血或红细胞锌含量作为暴露标志,有助于未来研究成果的临床转化。虽然目前尚不能确认母体锌缺乏与后代出生缺陷风险升高之间存在因果关系,但并无增补锌的副作用方面的报道。因此,妇女围受孕期服用含锌的多种微量营养素,应有助于降低出生缺陷的风险。

| [1] | Haase H, Mocchegiani E, Rink L. Correlation between zinc status and immune function in the elderly[J]. Biogerontology, 2006, 7(5-6): 421–428. DOI:10.1007/s10522-006-9057-3 |

| [2] | Plum LM, Rink L, Haase H. The essential toxin: impact of zinc on human health[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2010, 7(4): 1342–1365. DOI:10.3390/ijerph7041342 |

| [3] | Jyotsna S, Amit A, Kumar A. Study of serum zinc in low birth weight neonates and its relation with maternal zinc[J]. J Clin Diagn Res, 2015, 9(1): Sc01–03. |

| [4] | Maduray K, Moodley J, Soobramoney C, et al. Elemental analysis of serum and hair from pre-eclamptic South African women[J]. J Trace Elem Med Biol, 2017, 43: 180–186. DOI:10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.03.004 |

| [5] | Sandstead HH, Freeland-Graves JH. Dietary phytate, zinc and hidden zinc deficiency[J]. J Trace Elem Med Biol, 2014, 28(4): 414–417. DOI:10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.011 |

| [6] | Walker CLF, Ezzati M, Black RE. Global and regional child mortality and burden of disease attributable to zinc deficiency[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2008, 63(5): 591–597. |

| [7] | Lewicka I, Kocylowski R, Grzesiak M, et al. Selected trace elements concentrations in pregnancy and their possible role–literature review[J]. Ginekol Pol, 2017, 88(9): 509–514. DOI:10.5603/GP.a2017.0093 |

| [8] | Wilson RL, Grieger JA, Bianco-Miotto T, et al. Association between maternal zinc status, dietary zinc intake and pregnancy complications: a systematic review[J]. Nutrients, 2016, 8(10): e641. DOI:10.3390/nu8100641 |

| [9] | Jariwala M, Suvarna S, Kiran KG, et al. Study of the concentration of trace elements fe, zn, cu, se and their correlation in maternal serum, cord serum and colostrums[J]. Indian J Clin Biochem, 2014, 29(2): 181–188. DOI:10.1007/s12291-013-0338-8 |

| [10] | Hurley LS. Teratogenic aspects of manganese, zinc, and copper nutrition[J]. Physiol Rev, 1981, 61(2): 249–295. DOI:10.1152/physrev.1981.61.2.249 |

| [11] | 中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 卫生部发布《中国出生缺陷防治报告(2012)》[EB/OL]. (2012 – 09 – 12). [2017 – 12 – 10]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/wsb/pxwfb/201209/55840.shtml. |

| [12] | 康份红. 不同水平锌缺乏对大鼠胚胎心脏发育的影响及其可能机制的探讨[D]. 福州: 福建医科大学, 2009. |

| [13] | 曾芳. 锌对高同型半胱氨酸诱导鼠胚心脏畸形的干预研究[D]. 福州: 福建医科大学, 2008. |

| [14] | Jameson S. Zinc and copper in pregnancy, correlations to fetal and maternal complications[J]. Acta Med Scand Suppl, 1976, 593: 5–20. |

| [15] | 张雪娟, 赵志华, 尤爱平, 等. 围产儿先天性心脏病的相关因素的病例对照研究[J]. 中国优生与遗传杂志, 2013, 21(9): 86–88. |

| [16] | 赖彩芹. 围孕期营养素及母胎Jaggedl基因多态性与先天性心脏病的相关研究[D]. 广州: 南方医科大学, 2015. |

| [17] | Hu H, Liu Z, Li J, et al. Correlation between congenital heart defects and maternal copper and zinc concentrations[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2014, 100(12): 965–972. DOI:10.1002/bdra.23284 |

| [18] | Brownie CF, Brownie C, Noden D, et al. Teratogenic effect of calcium edetate (CaEDTA) in rats and the protective effect of zinc[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 1986, 82(3): 426–443. DOI:10.1016/0041-008X(86)90278-4 |

| [19] | Hurley LS, Swenerton H. Congenital malformations resulting from zinc deficiency in rats[J]. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med, 1966, 123(3): 692–696. DOI:10.3181/00379727-123-31578 |

| [20] | Warkany J, Petering HG. Congenital malformations of the central nervous system in rats produced by maternal zinc deficiency[J]. Teratology, 1972, 5(3): 319–334. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9926 |

| [21] | Quinn PB, Cremin FM, O'Sullivan VR, et al. The influence of dietary folate supplementation on the incidence of teratogenesis in zinc-deficient rats[J]. Br J Nutr, 1990, 64(1): 233–243. DOI:10.1079/BJN19900025 |

| [22] | Krapels IP, Rooij IA, Wevers RA, et al. Myo-inositol, glucose and zinc status as risk factors for non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in offspring: a case-control study[J]. Bjog, 2004, 111(7): 661–668. DOI:10.1111/bjo.2004.111.issue-7 |

| [23] | Tamura T, Munger RG, Corcoran C, et al. Plasma zinc concentrations of mothers and the risk of nonsyndromic oral clefts in their children: a case-control study in the Philippines[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2005, 73(9): 612–616. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1542-0760 |

| [24] | Hozyasz KK, Ruszczynska A, Bulska E. Low zinc and high copper levels in mothers of children with isolated cleft lip and palate[J]. Wiad Lek, 2005, 58(7-8): 382–385. |

| [25] | Hozyasz KK, Kaczmarczyk M, Dudzik J, et al. Relation between the concentration of zinc in maternal whole blood and the risk of an infant being born with an orofacial cleft[J]. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2009, 47(6): 466–469. DOI:10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.06.005 |

| [26] | Wallenstein MB, Shaw GM, Yang W, et al. Periconceptional nutrient intakes and risks of orofacial clefts in California[J]. Pediatr Res, 2013, 74(4): 457–465. DOI:10.1038/pr.2013.115 |

| [27] | 杨元, 汪思顺, 潘钦瑞, 等. 唇腭裂家庭环境及膳食营养状况调查分析[J]. 中国优生与遗传杂志, 2007, 15(10): 88–89. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-9534.2007.10.052 |

| [28] | Munger RG, Tamura T, Johnston KE, et al. Plasma zinc concentrations of mothers and the risk of oral clefts in their children in Utah[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2009, 85(2): 151–155. DOI:10.1002/bdra.v85:2 |

| [29] | McKinney CM, Pisek A, Chowchuen B, et al. Case-control study of nutritional and environmental factors and the risk of oral clefts in Thailand[J]. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol, 2016, 106(7): 624–632. DOI:10.1002/bdra.v106.7 |

| [30] | Hurley LS. Trace elements and teratogenesis[J]. Med Clin North Am, 1976, 60(4): 771–778. DOI:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)31860-0 |

| [31] | Cavdar AO, Arcasoy A, Baycu T, et al. Zinc deficiency and anencephaly in Turkey[J]. Teratology, 1980, 22(1): 141. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9926 |

| [32] | Cavdar AO, Babacan E, Asik S, et al. Zinc levels of serum, plasma, erythrocytes and hair in Turkish women with anencephalic babies[J]. Prog Clin Biol Res, 1983, 129: 99–106. |

| [33] | Cavdar AO, Bahceci M, Akar N, et al. Maternal hair zinc concentration in neural tube defects in Turkey[J]. Biol Trace Elem Res, 1991, 30(1): 81–85. DOI:10.1007/BF02990344 |

| [34] | Demir N, Basaranoglu M, Huyut Z, et al. The relationship between mother and infant plasma trace element and heavy metal levels and the risk of neural tube defect in infants[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2017, 3: 1–8. |

| [35] | Velie EM, Block G, Shaw GM, et al. Maternal supplemental and dietary zinc intake and the occurrence of neural tube defects in California[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1999, 150(6): 605–616. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010059 |

| [36] | Groenen PM, Peer PG, Wevers RA, et al. Maternal myo-inositol, glucose, and zinc status is associated with the risk of offspring with spina bifida[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2003, 189(6): 1713–1719. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00807-X |

| [37] | Carrillo-Ponce ML, Martinez-Ordaz VA, Velasco-Rodriguez VM, et al. Serum lead, cadmium, and zinc levels in newborns with neural tube defects from a polluted zone in Mexico[J]. Reprod Toxicol, 2004, 19(2): 149–154. DOI:10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.07.003 |

| [38] | Cengiz B, Söylemez F, Öztürk E, et al. Serum zinc, selenium, copper, and lead levels in women with second-trimester induced abortion resulting from neural tube defects: a preliminary study[J]. Biol Trace Elem Res, 2004, 97(3): 225–235. DOI:10.1385/BTER:97:3 |

| [39] | Yan L, Wang B, Li Z, et al. Association of essential trace metals in maternal hair with the risk of neural tube defects in offspring[J]. Birth Defects Res, 2017, 109(3): 234–243. DOI:10.1002/bdr2.v109.3 |

| [40] | 张卫, 任爱国, 裴丽君, 等. 微量元素与神经管畸形关系的病例对照研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2005, 26(10): 48–52. |

| [41] | 赵灵琴, 徐惠英, 颜崇淮, 等. 铅汞等重金属元素与神经系统畸形发生的关系研究[J]. 中国优生与遗传杂志, 2008, 16(5): 94–96, 107. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-9534.2008.05.049 |

| [42] | Rogers JM, Taubeneck MW, Daston GP, et al. Zinc deficiency causes apoptosis but not cell cycle alterations in organogenesis-stage rat embryos: effect of varying duration of deficiency[J]. Teratology, 1995, 52(3): 149–159. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9926 |

| [43] | Jankowski MA, Uriu-Hare JY, Rucker RB, et al. Maternal zinc deficiency, but not copper deficiency or diabetes, results in increased embryonic cell death in the rat: implications for mechanisms underlying abnormal development[J]. Teratology, 1995, 51(2): 85–93. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9926 |

| [44] | Lopez V, Keen CL, Lanoue L. Prenatal zinc deficiency: influence on heart morphology and distribution of key heart proteins in a rat model[J]. Biol Trace Elem Res, 2008, 122(3): 238–255. DOI:10.1007/s12011-007-8079-2 |

| [45] | Wong SH, Zhao Y, Schoene NW, et al. Zinc deficiency depresses p21 gene expression: inhibition of cell cycle progression is independent of the decrease in p21 protein level in HepG2 cells[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2007, 292(6): C2175–2184. DOI:10.1152/ajpcell.00256.2006 |

| [46] | Adamo AM, Zago MP, Mackenzie GG, et al. The role of zinc in the modulation of neuronal proliferation and apoptosis[J]. Neurotox Res, 2010, 17(1): 1–14. DOI:10.1007/s12640-009-9067-4 |

| [47] | Cui L, Takagi Y, Wasa M, et al. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitor attenuates intestinal damage induced by zinc deficiency in rats[J]. J Nutr, 1999, 129(4): 792–798. DOI:10.1093/jn/129.4.792 |

| [48] | Aimo L, Cherr GN, Oteiza PI. Low extracellular zinc increases neuronal oxidant production through nadph oxidase and nitric oxide synthase activation[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2010, 48(12): 1577–1587. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.040 |

| [49] | Oteiza PI, Olin KL, Fraga CG, et al. Zinc deficiency causes oxidative damage to proteins, lipids and DNA in rat testes[J]. J Nutr, 1995, 125(4): 823–829. |

| [50] | Carter JE, Truong-Tran AQ, Grosser D, et al. Involvement of redox events in caspase activation in zinc-depleted airway epithelial cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2002, 297(4): 1062–1070. DOI:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02292-1 |

| [51] | Song Y, Leonard SW, Traber MG, et al. Zinc deficiency affects DNA damage, oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and DNA repair in rats[J]. J Nutr, 2009, 139(9): 1626–1631. DOI:10.3945/jn.109.106369 |

| [52] | Song Y, Chung CS, Bruno RS, et al. Dietary zinc restriction and repletion affects DNA integrity in healthy men[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009, 90(2): 321–328. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27300 |

| [53] | Uriu-Adams JY, Keen CL. Zinc and reproduction: effects of zinc deficiency on prenatal and early postnatal development[J]. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol, 2010, 89(4): 313–325. DOI:10.1002/bdrb.20264 |

| [54] | Duffy JY, Overmann GJ, Keen CL, et al. Cardiac abnormalities induced by zinc deficiency are associated with alterations in the expression of genes regulated by the zinc-finger transcription factor GATA-4[J]. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol, 2004, 71(2): 102–109. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1542-9741 |

| [55] | Krezel A, Hao Q, Maret W. The zinc/thiolate redox biochemistry of metallothionein and the control of zinc ion fluctuations in cell signaling[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2007, 463(2): 188–200. DOI:10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.017 |

2018, Vol. 34

2018, Vol. 34