2. 四川省疾病预防控制中心;

3. 成都市疾病预防控制中心

研究显示,particulate matter less than 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter (PM10)对人群过早死亡可能存在弱的滞后效应[1 – 2],但不同地区因PM10成分、浓度和构成差异[3],PM10急性死亡影响研究结果不一致。近年研究显示,温度尤其是极端天气对急性死亡影响更显著,甚至有研究认为气温变化才是导致死亡的真正原因,颗粒物可能对人群死亡并无显著影响[4]。温度是分析PM10急性死亡影响常用的预测因子,但一般研究关注的重点是在回归模型中调整温度等变量后观察PM10的过早死亡风险,目前专门研究PM10急性死亡影响温度差异的文献较少[5 – 7]。为观察雾霾期间PM10是否对人群急性死亡产生显著影响,本研究以2013 — 2016年成都市≥65岁以上老年人(高危死亡人群)为研究对象,采用分布滞后非线性模型 [8 – 9](distributed lag nonlinear model,DLNM),分析雾霾典型城市成都[10]PM10短期波动在不同温度范围条件下对老年人死亡风险的差异,从而为雾霾污染防治提供基础科研数据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 资料来源成都市≥65岁老年人死亡统计数据来自四川省疾病预防控制中心2013年1月1日 — 2016年12月31日居民死因登记数据,同期PM 10监测数据及气温等气象监测数据分别来源于成都市环境监测中心和成都市气象监测站。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 数据清理方法本研究使用R软件(R3.4.1版本)对数据进行整理。以“名字”“身份证号码”“性别”“出生日期”和“年龄”为关键词,查找并删除重复补报死亡案例,校对死因编码(International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, ICD-10[11])准确性,并将死亡原因分为非意外死亡、呼吸系统疾病、心血管疾病和癌症四类;PM10以成都市国家监测点日均PM10几何均值代表成都地区PM10的平均水平,并以成都全市范围气温、气湿代表成都地区的平均温湿度水平。

1.2.2 建模方法因死亡数据存在过度离势,本研究采用DLNM Quasipoisson分布回归模型拟合PM10暴露–反应关系和暴露–滞后效应[12–13],将成都市日平均PM10浓度和日平均温度以交叉基的形式纳入模型,以quasi-AKaike Information Criterion(QAIC)准则选择模型的自由度,同时控制湿度、气压、长期趋势、星期几效应、节假日效应等混杂因素,探讨PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应。

| $\begin{aligned} Log\left[ {E\left( {{Y_t}} \right)} \right] = & \alpha + cb\left( {PM} \right) + cb\left( {Temp} \right) + \\& ns\left( {Time,df \!=\! 7\! \times \!4} \right) \!+\! ns\left( {RH,df \!= \!3} \right)\! + \\& ns\left( {P,df = 3} \right) + Dow + Holiday\end{aligned}$ | (1) |

式中:Yt为第t日死亡人数;α为常数项;cb为交叉基函数;PM为第t日PM10的日平均浓度,PM10基函数选择线性函数,PM10滞后项的基函数选择多项式函数;Temp表示第t日的日平均温度,温度及其滞后项的基函数均选择自然立方样条函数;ns代表自然立方样条函数;df代表自由度;Time表示长期趋势,自由度为7/年,共4年;RH为日均相对湿度,自由度为3;P为日均气压,自由度为3;Dow代表星期几效应;Holiday为节假日效应。

1.2.3 参数选择方法根据以往研究[14],选择湿度和气压的自由度为3;温度的交叉基中,选择温度及其滞后项的自由度为5和4。根据本研究数据特征,调整PM10的最大滞后天数为7~30 d,并根据QAIC最小原则,选择最大滞后天数为15;调整时间趋势的自由度为5~9,并根据QAIC最小原则,自由度选择7/年。

1.2.4 气温分层方法本研究以P25和P75为百分位节点将日均气温分为低温[– 1.9℃,10.1℃)、中温[10.1℃,23.0℃)和高温[23.0℃,29.8℃]3层。

1.3 统计分析采用R软件(R3.4.1版本)进行数据的统计分析,采用广义线性模型和分布滞后模型,进行不同温度分层,探究不同温度条件下,PM10对老年人群死亡的影响。效应指标为相对危险度(RR),按照双侧检验P < 0.05确定差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果 2.1 PM10和日均气温对老年人过早死亡趋势影响 2.1.1 2013 — 2016年成都空气质量、气象条件及人群死亡情况( 表1)2013 — 2016年成都市PM 10日均浓度均值为115 μg/m3,其中共有355 d(24 %)PM10浓度超过国家二级标准(150 μg/m3),最高达861 μg/m3;同期成都市日均气温为16.8 ℃,其中低于0 ℃的天数为94 d,超过30℃高温天数为263 d。2013 — 2016年成都日均PM 10浓度、气温及死亡人数详见表1。

| 表 1 成都市2013—2016年日均PM10浓度、气温及死亡人数 |

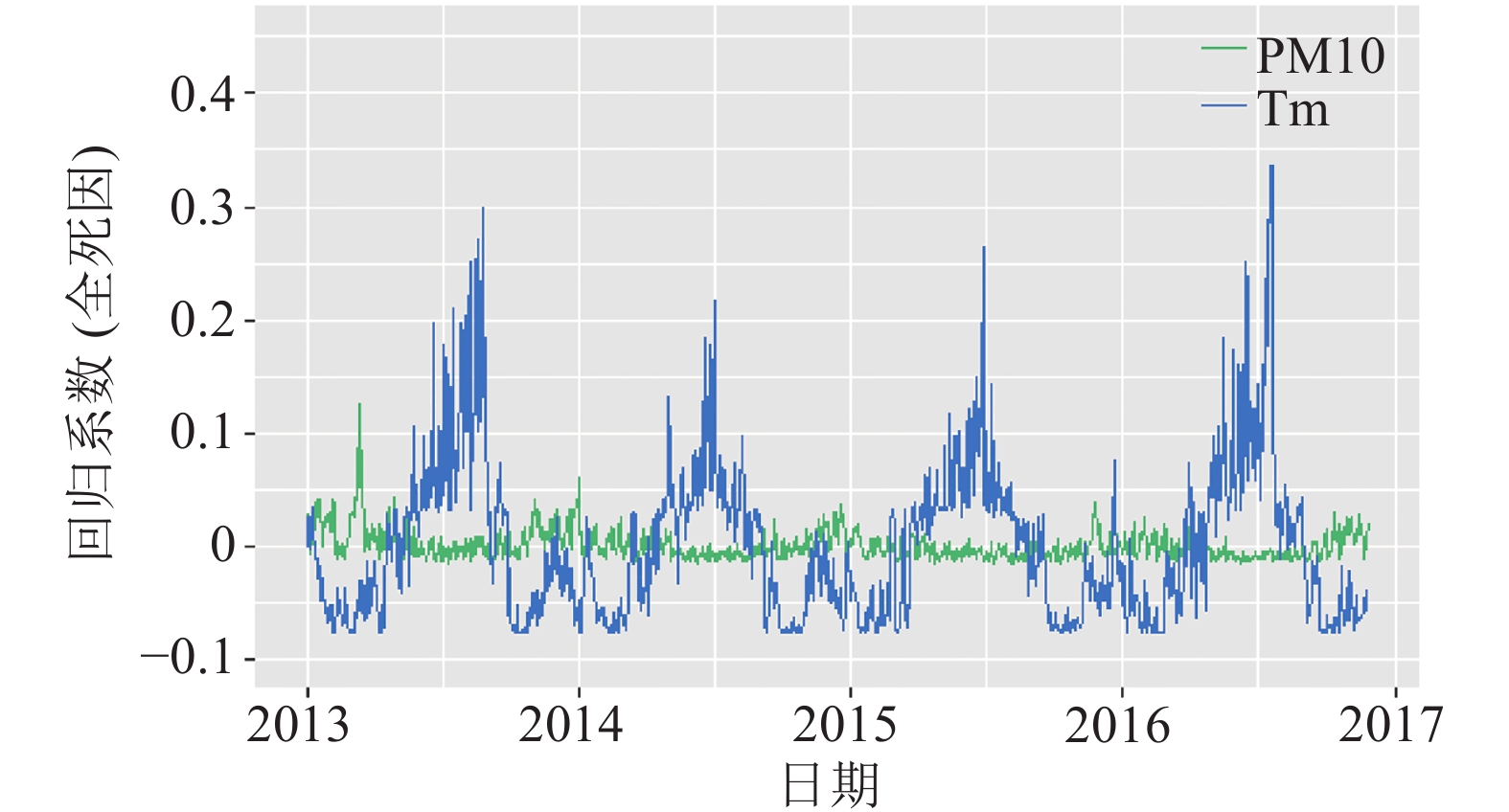

2.1.2 日均PM10和气温对老年人过早死亡影响时间趋势分析(图1)

调整时间趋势、星期几效应、节假日效应、相对湿度和平均气压,经广义线性模型拟合,PM10每增加1μg/m3,过早死亡风险增加0.017 %(95 % CI = 0.009 %~0.025 %);日均PM10和日均气温对成都市≥65岁老人的过早死亡影响具有时间和季节趋势,春秋季PM10和日均气温对过早死亡影响趋势相反,而在夏季高温时期,PM10和日均气温对过早死亡影响趋势一致。

|

注:图中Tm代表日均温度对老年人死亡影响的回归系数;PM10代表日均PM10对老年人群死亡影响的回归系数。 图 1 日均PM10和气温对老年人过早死亡影响的时间趋势 |

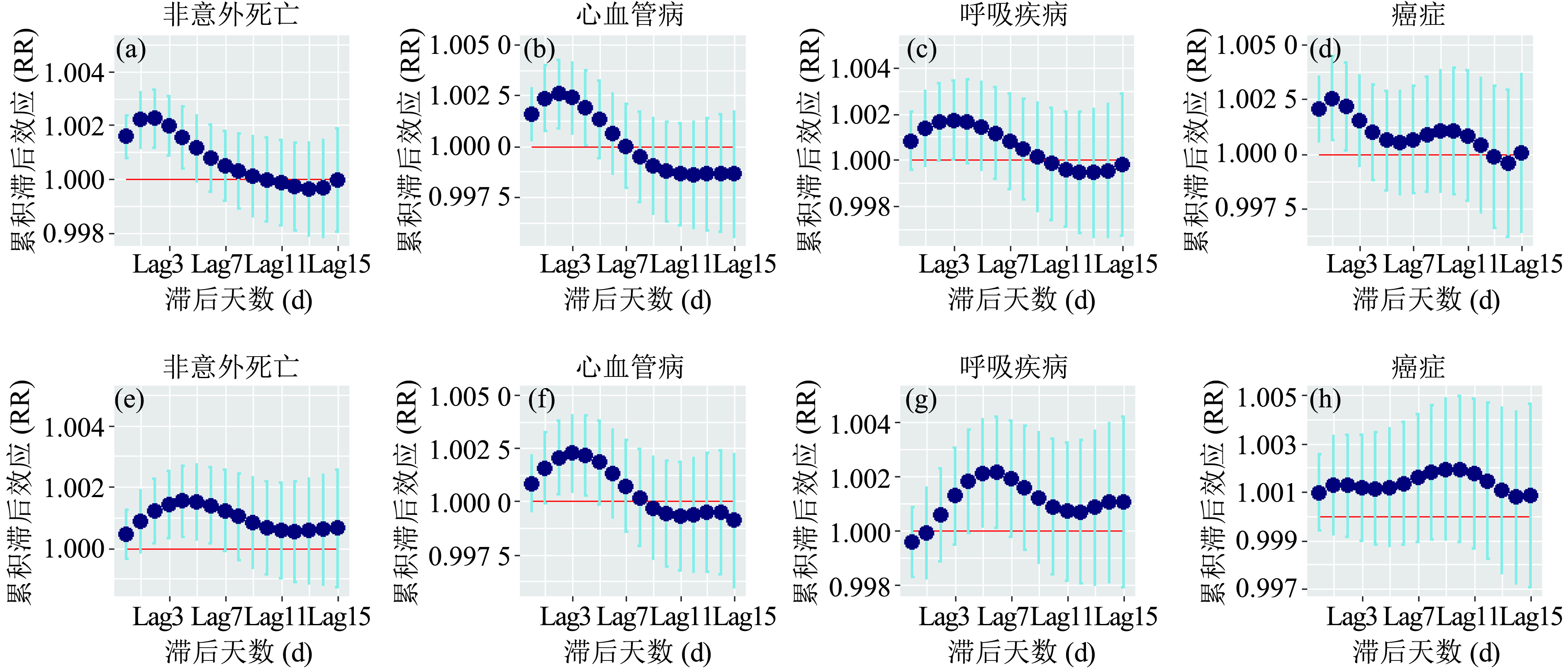

2.2 温度调整前后PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应 2.2.1 温度调整前PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应(图2)

在DLNM中调整时间趋势、星期几效应、节假日效应、相对湿度和平均气压,结果显示,PM10的短期波动对过早死亡的影响可持续3~5 d,PM10每增加10 μg/m3可使老年人的累积滞后死亡风险增加0.15 %~0.26 %,其中全死因(不含意外死亡)累积滞后死亡风险可持续5 d,并于滞后2 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.002, 95 % CI = 1.001~1.003);心血管病累积滞后死亡风险可持续5 d,并于滞后2 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.003, 95% CI = 1.001~1.004);癌症累积滞后死亡风险持续3 d,并于滞后1 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.003, 95 % CI = 1.001~1.004);但呼吸疾病的滞后累积效应无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

2.2.2 温度调整后PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应(图2)调整时间趋势、星期几效应、节假日效应、相对湿度和平均气压,并将日均温度和PM10同时带入模型。结果显示,同时调整温度后,PM10每增加10 μg/m3,PM10对老年人的累积滞后效应延迟,其中全死因(不含意外死亡)累积滞后死亡影响延迟2 d,持续作用5 d,并于滞后4 d时其累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.002, 95 % CI = 1.000~1.003);心血管病累积滞后死亡影响也延迟2 d,持续作用3 d,并于滞后3 d时其累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.002, 95 % CI = 1.001~1.004);呼吸系统疾病累积滞后死亡影响延迟5 d,持续作用2 d,并于滞后6 d时其累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.002, 95 % CI = 1.000~1.004);但癌症的累积滞后死亡风险无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。

|

注:图中累积滞后效应(RR)为累积滞后死亡风险的相对危险度及其95 % 置信区间;Lag为滞后天数;a~d为调整温度前PM10对非意外全死因、心血管病、呼吸疾病和癌症死亡的累积滞后风险,e~h为调整温度后PM10对非意外全死因、心血管病、呼吸疾病和癌症死亡的累积滞后风险。 图 2 调整日均气温前后PM10对老年人过早死亡影响累积滞后效应 |

2.3 不同温度范围 PM10 对老年人过早死亡累积滞后效应(表 2)

按四分位数对温度分层,调整时间趋势、星期几效应、节假日效应、温度、相对湿度和日均气压,结果显示,低温[– 1.9 ℃,10.1 ℃)时 PM10对老年人的过早死亡滞后累积影响无统计学意义(P > 0.05);在中等温度[10.1 ℃, 23.0 ℃)时,PM 10 每增加10 μg/m3,PM10 对老年人的全死因(不含意外死亡)累积滞后死亡风险可持续4 d,并于滞后1 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.003, 95 % CI = 1.001~1.005);心血管病累积滞后死亡风险可持续3 d,并于滞后1 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.003, 95 % CI =1.001~1.006);癌症累积滞后死亡风险持续4 d,并于滞后1 d时累积死亡风险最大(RR = 1.005, 95 % CI =1.002~1.009);呼吸系统疾病患者的滞后累积效应无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。在高温(23.0 ℃,29.8 ℃]时,PM 10每增加10 μg/m3,全死因(不含意外死亡)累积滞后死亡风险可持续10 d,滞后9 d时累积死亡风险RR值为1.035(95 % CI = 1.001~1.070);心血管病累积滞后死亡风险可持续9 d,滞后8 d时累积死亡风险RR值为1.033(95 % CI = 1.002~1.064);但高温范围PM10对呼吸系统和癌症未见显著的累积滞后死亡效应(P > 0.05)。

| 表 2 不同温度范围日均PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应 |

3 讨 论

相关研究显示,当温度适宜时,日均气温与人群过早死亡负相关,由于日均气温与过早死亡的关联为强关联(RR > 3.0) [15],因此舒适的温度可能对PM10的滞后死亡影响(弱效应)有一定的缓冲。为了观察雾霾典型区域PM10对死亡的急性影响是否完全被温度效应修饰,本研究利用DLNM分析了PM10在不同的温度范围对成都市≥65岁老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应。

本研究结果显示,日均气温对PM10的累积滞后死亡影响有显著的修饰作用,当温度与死亡负相关时(β < 0),可能因气温的保护作用强于PM 10的滞后效应,在此温度范围本研究未观察到PM10对老年人过早死亡存在显著的累积滞后影响;而当温度与死亡正相关时(β > 0),因温度的修饰作用PM 10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后效应较小,虽然其效应较弱(RR < 1.10),但其效应可能与温度的死亡影响叠加。即虽然PM 10每增加10 μg/m3,老年人的累积过早死亡风险(RR)仅为1.003~1.035,但不应因其为弱效应而不重视PM10的防控,因为这一弱效应可能是基于同期温度的累积效应而产生的协同死亡影响。

有研究显示,冬季颗粒物对人群死亡的急性影响多高于夏季[16 – 18],但本研究却发现随着气温升高PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后影响增强。Pascal M研究法国9个城市颗粒物急性死亡影响时也曾发现,夏季及高温热浪时期PM10的急性死亡影响高于PM10在低温天气对死亡的影响[19]。其原因可能在于成都冬季没有极寒天气,其冬季温度对死亡的影响不突出;随着温度升高,老年人外出活动时间增多,PM10暴露机会也相对增多,此外虽然成都夏季PM10浓度相对较低[20],但因相对湿度大和特殊的盆地地形,空气易静稳并使得PM10等污染物无法快速消散[21],PM10对居民持续累积作用时间相对延长,再加上高温使血管扩张及呼吸加快,人群暴露量相对增加,因此成都夏季的PM10对老年人的累积滞后死亡影响更为突出。

本研究结果还显示,调整日均气温后PM10对死亡的累积影响出现滞后延迟的现象,这种现象在以往研究中较少关注。这种滞后效应延迟的现象是否为温度与PM10对急性死亡协同影响的一般特征还有待进一步研究;但此现象提示,雾霾健康影响的预警可能需要结合未来几天的温度变化预测累积滞后死亡风险。PM10对死亡影响一般以心血管病和呼吸疾病影响为主,但本研究却发现调整温度或对温度分层后,PM10对全死因(非意外)死亡的累积滞后影响持续时间最长,其可能原因为我们的观察对象为≥65岁老年人,而老年人中癌症等免疫力低者居多,虽然PM10不一定对免疫低下患者过早死亡产生直接影响,但PM10可能会通过激发呼吸道的炎症而增加老年人的死亡风险[22]。

综上所述,本研究结果提示PM10对老年人过早死亡的累积滞后影响不可忽略,尤其在高温天气时应预警PM10对老年人的滞后死亡风险。

志谢 感谢环保部华南科学研究所、四川省疾病预防控制中心环境与学校卫生消毒所、成都市疾病预防控制中心和成都市青羊区疾病预防控制中心对本项目研究的支持

| [1] | Shang Y, Sun Z, Cao J, et al. Systematic review of Chinese studies of short-term exposure to air pollution and daily mortality[J]. Environment International, 2013, 54(4): 100–111. |

| [2] | Tsai SS, Chang CC, Liou SH, et al. The effects of fine particulate air pollution on daily mortality: a case-crossover study in a subtropical city, Taipei, Taiwan[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2014, 11(5): 5081–5093. DOI:10.3390/ijerph110505081 |

| [3] | 徐甜, 王志远, 张兵, 等. 中国环境保护重点城市空气质量指数时空变化特征[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2016, 32(8): 1027–1031. DOI:10.11847//zgggws2016-32-08-06 |

| [4] | Cox T, Popken D, Ricci PF. Temperature, not fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is causally associated with short-term acute daily mortality rates: results from one hundred united states cities [J]. Dose-Response, 2013, 11(3): 319–343. |

| [5] | Wang Y, Kloog I, Coull BA, et al. Estimating causal effects of long-term PM2.5 exposure on mortality in New Jersey [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2016, 124(8): 1182–1188. |

| [6] | 张云权, 吴凯, 朱慈华, 等. 武汉大气污染与缺血性心脏病死亡关系季节差异[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2015, 31(7): 926–929. DOI:10.11847/zgggws2015-31-07-19 |

| [7] | Xia M, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, et al. Temperature modifies the acute effect of particulate air pollution on mortality in eight Chinese cities[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2012, 435-436(7): 215–221. |

| [8] | Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Kenward MG, et al. Distributed lag non-linear models[J]. Statistics in Medicine, 2010, 29(21): 2224–2234. DOI:10.1002/sim.v29:21 |

| [9] | Gasparrini A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: the package dlnm[J]. Journal of Statistical Software, 2011, 43(8): 1–20. |

| [10] | Qiao X, Jaffe D, Tang Y, et al. Evaluation of air quality in Chengdu, Sichuan Basin, China: are China’s air quality standards sufficient yet?[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2015, 187(5): 250. DOI:10.1007/s10661-015-4500-z |

| [11] | Allanson E, Tuncalp O, Gardosi J, et al. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period: ICD-PM: results from pilot database testing in South Africa and United Kingdom[J]. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2016, 123(12): 2019–2028. DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.14244 |

| [12] | Gasparrini A. Modeling exposure-lag-response associations with distributed lag non-linear models[J]. Statistics in Medicine, 2014, 33(5): 881–899. DOI:10.1002/sim.5963 |

| [13] | Solimini AG, Renzi M. Association between air pollution and emergency room visits for atrial fibrillation[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017, 14(6): 661. DOI:10.3390/ijerph14060661 |

| [14] | Guo Y, Punnasiri K, Tong S, et al. Effects of temperature on mortality in Chiang Mai city, Thailand: a time series study[J]. Environmental Health, 2012, 11(1): 36–36. DOI:10.1186/1476-069X-11-36 |

| [15] | Guo Y, Barnett AG, Pan X, et al. The impact of temperature on mortality in Tianjin, China: a case-crossover design with a distributed lag nonlinear model[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2011, 119(12): 1719–1725. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1103598 |

| [16] | Chen R, Peng RD, Meng X, et al. Seasonal variation in the acute effect of particulate air pollution on mortality in the China Air Pollution and Health Effects Study (CAPES)[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2013: 259–265. |

| [17] | Tsai S, Chen C, Yang C, et al. Short-term effect of fine particulate air pollution on daily mortality: a case-crossover study in a tropical city, Kaohsiung, Taiwan[J]. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, 2014, 77(8): 467–477. DOI:10.1080/15287394.2014.881247 |

| [18] | Vardoulakis S, Dear K, Hajat S, et al. Comparative assessment of the effects of climate change on heat- and cold-related mortality in the United Kingdom and Australia[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2014, 122(12): 1285–1292. |

| [19] | Pascal M, Falq G, Wagner V, et al. Short-term impacts of particulate matter (PM10,PM10-2.5, PM2.5) on mortality in nine French cities [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 95(1): 175–184. |

| [20] | Li Y, Chen Q, Zhao H, et al. Variations in PM10, PM2.5 and PM0.1 in an urban area of the Sichuan Basin and their relation to meteorological factors [J]. Atmosphere, 2015, 6(1): 150–163. DOI:10.3390/atmos6010150 |

| [21] | Wang Y, Zhang X, Sun J Y, et al. Spatial and temporal variations of the concentrations of PM 10, PM 2.5 and PM 1 in China[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 2015, 15(23): 13585–13598. DOI:10.5194/acp-15-13585-2015 |

| [22] | Guarnieri M, Balmes J R. Outdoor air pollution and asthma[J]. The Lancet, 2014, 383(9928): 1581–1592. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6 |

2018, Vol. 34

2018, Vol. 34