2. 北京大学肿瘤医院暨北京市肿瘤防治研究所放疗科/恶性肿瘤发病机制及转化研究教育部重点实验室, 北京 100142;

3. 中国疾病预防控制中心, 北京 100088

2. Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research (Ministry of Education/Beijing), Department of Radiation Oncology, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing 100142 China;

3. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100088 China

宫颈癌是最常见的妇科恶性肿瘤,据估计,2020 年全球约有

以往的研究表明,宫颈癌患者放化疗期间 HT 的发生与盆腔骨髓结构(pelvic bone marrow,PBM)的剂量学参数(如 V5、V10、V20 和 V30)之间存在强相关性[9-12]。现有研究大多采用放化疗期间HT最高的分级作为该患者的最终分级,但由于宫颈癌根治性放化疗方案和治疗周期差别较大,导致该关注期跨度较大,得出的研究结果的可靠性值得进一步探讨。

本研究回顾性分析556例宫颈癌根治性放化疗病例,在关注的放疗周期内(放疗前一个月至放疗后一周),深入探讨病理分期、分型、年龄和是否化疗等临床特征以及骨盆骨结构的剂量体积参数与AHT之间的相关性和潜在影响,为宫颈癌放化疗的治疗策略提供更为科学的参考。

1 资料与方法 1.1 病例选择本研究选择723例于2009年1月—2021年4月期间在北京肿瘤医院诊疗的分期为IA-IVb的宫颈癌患者进行回顾性分析。纳入标准包括病理证实为宫颈癌的患者,无远处转移迹象,无肾病、肝病、血液病或其他系统性疾病病史;放疗开始前 1 周内进行全血细胞计数(CBC)检验,治疗期间每周进行1次全血常规检查。排除以下患者:(1) 盆腔放疗或全身化疗史;(2) 放疗前长期严重贫血;(3) 处方剂量不一致、血常规数据不完整或未完成整个放疗疗程;(4) 排除有其他恶性肿瘤或复发性肿瘤病史的患者,以及因严重血液毒性以外的原因经历过化疗暂停或放疗中断次数过多(中断次数大于 7 次)的患者。

1.2 靶区和危及器官勾画及治疗方案肿瘤体积(gross tumor volume,GTV)和临床靶区(clinical tumor volume,CTV)以及膀胱、直肠等危机器官均由2名临床经验丰富的医生在瓦里安公司Eclipse治疗计划系统(版本号:13.6和15.6)上根据肿瘤放疗组(radiotherapy oncology group ,RTOG)指南 [13-15]进行轮廓勾画,以确保感兴趣区(region of interest,ROI)划分的一致性和准确性。

根据以往研究,本研究主要选择2个感兴趣区(ROI)进行后续分析,包括股骨头(femoral head,FH)和骨盆骨结构(bone marrow,BM)。其中BM被定义为潜在照射范围内的整个骨骼结构,包括髂骨、耻骨、峡部、骶骨的骨髓体积,以及由第一腰椎至第五腰椎上界的骨髓体积。这种严格的 ROI 定义方法使得在制定治疗计划时对患者的潜在照射量和辐射毒性的评估更加可靠。所有 ROI 均由1名资深(15 年以上经验)医生确认。如果在 ROI 划分上存在一些分歧,2位医生将通过讨论获得一致的 ROI。

模拟定位和整个放疗流程中,患者处于仰卧位,为保持膀胱充盈度的一致性,需在治疗前1 h排空膀胱和直肠后摄入500 mL水。腹部盆腔CT扫描使用西门子SOMATOM Sensation开放式CT获得,采用连续扫描方式,层厚为5 mm,分辨率为512 × 512,像素大小为1.3 mm × 1.3 mm。

1.3 治疗方案纳入病例均采用调强放射治疗(intensity modulated radiation therapy,IMRT)或容积调强放射治疗(volumetric intensity modulated radiation therapy,VMAT)技术,分别在IX或TrueBeam型号医用直线加速器上完成治疗。2种治疗技术在实现方法和剂量学分布上略有差异,但均可以满足临床要求[16],其中在TrueBeam型号加速器上的病例均采用铅门跟随技术,以减少多叶光栅透漏射对周围正常组织的影响[17]。

根据2022版宫颈癌NCCN指南[18-19],纳入病例主要采用以下2种方案:(1) 每周一次单药顺铂,每隔7 d重复一次,共4~6个周期;(2) 每周3次联合方案,每隔21 d重复一次,共1~3个周期。所有患者都应在每个化疗周期前进行血常规检查。如果中性粒细胞计数低于 1.5 × 109/L,或血小板计数低于 100 × 109/L,化疗将被推迟执行。

1.4 评价参数本研究提取了2类评价参数,包括患者临床因素和剂量评价参数。临床因素包括患者年龄、临床分期、病理类型、关注期内是否化疗等参数。剂量参数包括平均剂量和基于体积的指标Vx,其中Vx代表接受超过x Gy辐射剂量的体积百分比。本研究采用了BM和FH的平均剂量和 V5、V10、V15、V20、V25、V30、V35、V40、V45 、V50等参数纳入分析。为了便于提取 ROI 的体积和剂量因子,本研究使用 Eclipse TPS 15.6 版提供的 Eclipse脚本应用程序编程接口(scripting application programming interface,ESAPI)研究者模式开发了基于 C# 的脚本进行批量处理。

1.5 急性血液毒性分级急性HT分级按照放射治疗肿瘤学组(RTOG)列出的标准进行划分[20],白细胞、中性粒细胞、血小板或血红蛋白减少达到3级或以上的患者被认为是急性HT。发生HT的时间被定义为从开始放疗到患者出现最严重的HT症状的时间[21]。

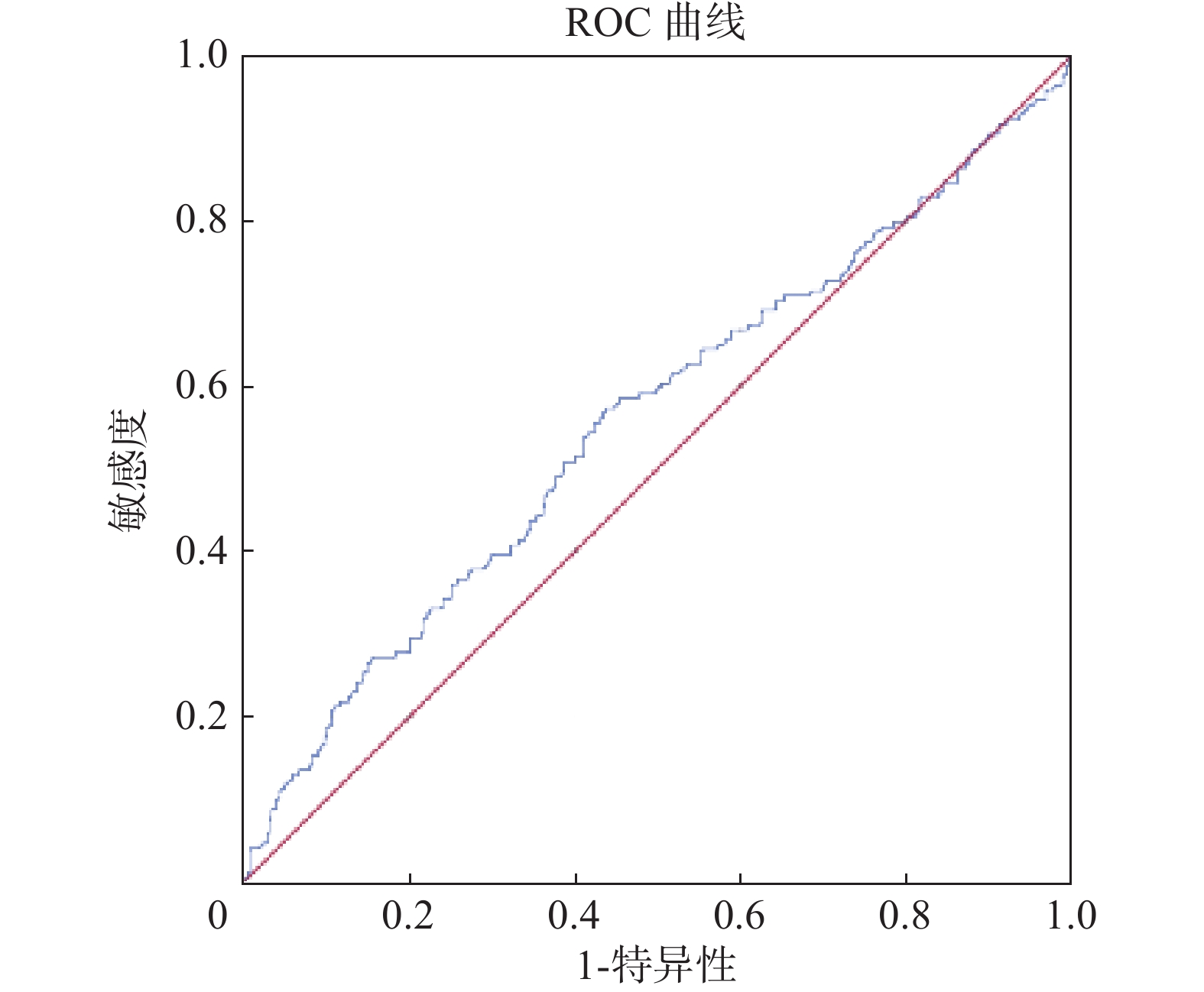

1.6 统计学方法本研究采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计学处理,对于连续变量,使用Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S 检验)判定其正态性,对于服从正态数据分布的评价参数(P > 0.05),采用独立样本T检验,反之使用非参数检验(Mann-Whitney U检验)。临床特征的分类变量采用χ2检验。经上述单因素逻辑分析后,对急性HT有显著影响的变量采用逻辑回归。采用受试者工作特征(receiver operating characteristic, ROC)曲线判断骨髓抑制的剂量体积临界值,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果 2.1 临床资料及分析最终纳入556名患者,进行回顾性分析,其中包括169名在关注期内发生AHT症状(grade ≥ 3)的患者。556例患者中,62例未发生任何骨髓抑制现象,分别有133例、192例、147例和22例发生1级、2级、3级和4级HT。≥ 3级骨髓抑制发生率为30.40%(169/556)。本研究得到了北京肿瘤医院伦理委员会的批准。

对宫颈癌放疗患者出现AHT的临床特征进行了回顾性分析,详见表1,结果显示,纳入病例的年龄分组和病理分期以及是否化疗等3个参数,均具有统计学意义。

|

|

表 1 宫颈癌放化疗患者临床特征卡方分析 Table 1 Chi-square analysis of clinical characteristics of patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer |

由于均不服从正态分布,对2个ROI的剂量学数据采用Mann-Whitney U检验,结果详见表2。由表2可知,BM和FH的mean dose、V5、V10、V15、V20、V25,以及FH的V35等剂量学参数与AHT的发生均具有统计学意义。

|

|

表 2 BM和FH剂量参数的独立样本T检验 Table 2 Independent samples t-tests for dosimetric parameters of bone marrow and femoral head |

对单因素分析中获得的与AHT发生相关的剂量学因素采用Logistic多元回归分析,得出BM的V15 AHT的发生有显著相关性(P=0.041,表3),提示骨盆V15是AHT的独立危险因素。

|

|

表 3 与AHT相关的剂量学参数二元Logistic回归分析 Table 3 Binary logistic regression analysis of dosimetric parameters associated with AHT |

对BM的V15进行ROC曲线分析(图1),AUC值、标准误、渐进显著性、95%置信区间以及对应的最佳阈值分别为0.559、0.027、0.027、0.505~0.613、84.29%。

|

图 1 骨盆骨结构剂量参数的ROC曲线 Figure 1 ROC curves for dosimetric parameters of pelvic bone marrow |

宫颈癌治疗中,放化疗同步应用可在一定程度上提升患者生存率,但大多伴随由辐射或药物引起的造血系统损伤(如AHT)的风险增加。ATH的主要根源在于造血干细胞受到损伤,这些细胞主要分布于成年人体内的红骨髓,其中扁平骨(如髋骨、骶骨、近端股骨和腰椎的下端)占全身红骨髓的50%以上[22-23],且处于宫颈癌常规外照射的范围之内。AHT对化疗方案的不利影响较少会导致治疗中断,并且考虑到化疗周期较长,患者可以依靠自身免疫和口服或注射升白药物治疗等手段予以改善。但AHT对于放疗的影响将会在一定程度上影响放疗进程甚至治疗中断。因此,在关注的放疗周期内,对于AHT的影响因素分析,更具临床价值。

现有的研究表明,BM的 V5、V10、V20 和 V30之间存在强相关性,并且可用作为AHT的预测因子。Corbeau等[24]的一项系统性文献综述显示,在接受顺铂为基础的 CRT 的 LACC 患者中,BM 的 V10(> 95%~75%)、V20(> 80%~65%)和 V40(37%~28%)与 AHT 显著相关。表明剂量学因素与 CRT 期间的AHT有一定的相关性,但由于样本量较小,或者出于样本均衡的考虑,得出的结论略有出入。此外,基于深度学习或影像组学方法的AHT预测类研究,其预测精度大多在0.6~0.85[8,25-26],从另一个侧面反映出,预测终点AHT的发生可能与影像特征、剂量特征或临床特征的发生有较大的相关性,但并不属于强相关( > 0.9)。

本研究将关注期设定为放疗前一个月至放疗后一周,是考虑到放疗前的化疗药物对AHT的影响,同时排除放疗周期结束后再行化学治疗的情况。由此在关注期内可将纳入病例分为放化同步组(CRT group)和单纯放疗组(RT alone group)。研究结果表明:(1)病例的年龄分组和病理分期2个临床特征,均具有统计学意义,与Zhu等[27] 、Rose等[28] 、Corbeau等[24]和Mahantshetty等[29]的研究结论一致;(2)在关注期内是否采用化学治疗的特征具有统计学意义,提示化疗药物在AHT的预测中的作用不可忽视,此后研究可以将纳入病例分组后再进一步探索;(3)逻辑回归结果显示,BM的V15 AHT的独立危险因素,与黄维等[30]的结果一致,不同的是该研究将预测终点设置为HT评分 ≥ 2级;(4)本研究对BM的V15进行ROC分析后,结果显示AUC为0.559,最佳阈值为84.29%。

本研究的局限在于:(1)未对纳入病例按照HT分级进行均衡化处理,在一定程度上导致ROC分析的AUC值较低,可能会导致最佳阈值的界定出现偏差;(2)未对纳入病例的病理分期进行筛选,或许局部晚期和早期宫颈癌病例,其AHT的影响因素会有较大差异;(3)本研究采用的BM的范围不包括双侧股骨头,而是分成2个ROI进行分析,可能会对结果有一定影响,但较符合临床实际情况。

总之,本研究结果显示,骨盆骨结构的V15是宫颈癌急性血液毒性的剂量学相关的独立高危因素,BM的V15限制在84.29%以下可以有效减少 ≥ 3级HT的发生。同时,骨盆V15可作为宫颈癌急性血液毒性的一个预测因子和评估参数。

| [1] |

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [2] |

Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, et al. Uterine neoplasms, version 1. 2023 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2023, 21(2): 181-209. DOI: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006.

|

| [3] |

Abu-Rustum NR. Management of recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2023, 21(5.5): 576-578. DOI:10.6004/jnccn.2023.5013 |

| [4] |

Dutta S, Nguyen NP, Vock J, et al. Image-guided radiotherapy and -brachytherapy for cervical cancer[J]. Front Oncol, 2015, 5: 6. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2015.00064 |

| [5] |

Radojevic MZ, Tomasevic A, Karapandzic VP, et al. Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients[J]. Open Med, 2020, 15(1): 822-832. DOI:10.1515/med-2020-0222 |

| [6] |

Parker K, Gallop-Evans E, Hanna L, et al. Five years’ experience treating locally advanced cervical cancer with concurrent chemoradiotherapy and high-dose-rate brachytherapy: results from a single institution[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2009, 74(1): 140-146. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1920 |

| [7] |

Wang WP, Hou XR, Yan JF, et al. Outcome and toxicity of radical radiotherapy or concurrent Chemoradiotherapy for elderly cervical cancer women[J]. BMC Cancer, 2017, 17(1): 510. DOI:10.1186/s12885-017-3503-2 |

| [8] |

Ren K, Shen L, Qiu JF, et al. Treatment planning computed tomography radiomics for predicting treatment outcomes and haematological toxicities in locally advanced cervical cancer treated with radiotherapy: A retrospective cohort study[J]. BJOG, 2023, 130(2): 222-230. DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.17285 |

| [9] |

Li N, Liu X, Zhai FS, et al. Association between dose-volume parameters and acute bone marrow suppression in rectal cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(54): 92904-92913. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.21646 |

| [10] |

Rahimy E, Von Eyben R, Lewis J, et al. Dosimetric and metabolic parameters predictive of hematologic toxicity in cervical cancer patients undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2021, 111(S3): e621. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.07.1652 |

| [11] |

Yan K, Ramirez E, Xie XJ, et al. Predicting severe hematologic toxicity from extended-field chemoradiation of para-aortic nodal metastases from cervical cancer[J]. Pract Radiat Oncol, 2018, 8(1): 13-19. DOI:10.1016/j.prro.2017.07.001 |

| [12] |

刘静雯, 任洪荣, 周冲, 等. 盆腔活性骨髓与宫颈癌放疗血液学毒性的关系[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2020, 29(6): 696-699. Liu JW, Ren HR, Zhou C, et al. Correlation between pelvic active bone marrow and hematological toxicity in radiotherapy of cervical cancer[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2020, 29(6): 696-699. DOI:10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2020.06.030 |

| [13] |

Gay HA, Barthold HJ, O’Meara E, et al. Pelvic normal tissue contouring guidelines for radiation therapy: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel atlas[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012, 83(3): E353-E362. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.023 |

| [14] |

Lim K, Small Jr W, Portelance L, et al. Consensus guidelines for delineation of clinical target volume for intensity-modulated pelvic radiotherapy for the definitive treatment of cervix cancer[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011, 79(2): 348-355. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.075 |

| [15] |

Small Jr W, Bosch WR, Harkenrider MM, et al. NRG oncology/RTOG consensus guidelines for delineation of clinical target volume for intensity modulated pelvic radiation therapy in postoperative treatment of endometrial and cervical cancer: an update[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2021, 109(2): 413-424. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.08.061 |

| [16] |

Sini C, Fiorino C, Perna L, et al. Dose-volume effects for pelvic bone marrow in predicting hematological toxicity in prostate cancer radiotherapy with pelvic node irradiation[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2016, 118(1): 79-84. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.020 |

| [17] |

曹丽媛, 鞠永健, 李克新. 钨门主动控制与被动跟随的剂量学差异性分析[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2023, 32(5): 556-559,564. Cao LY, Ju YJ, Li KX. Analysis of dosimetric differences between active control and passive tracking of jaws[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2023, 32(5): 556-559,564. DOI:10.13491/j.issn.1004-714X.2023.05.015 |

| [18] |

Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Bean S, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: cervical cancer, version 1.2020[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2020, 18(6): 660-666. DOI:10.6004/jnccn.2020.0027 |

| [19] |

Page G. NCCN Guidelines for Cervical Cancer V. 1.2022 – Annual on 06 / 11 / 21. Published online 2022: 10-11.

|

| [20] |

Cox JD, Stetz JA, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC)[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1995, 31(5): 1341-1346. DOI:10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C |

| [21] |

Liang Y, Messer K, Rose BS, et al. Impact of bone marrow radiation dose on acute hematologic toxicity in cervical cancer: Principal component analysis on high dimensional data[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2010, 78(3): 912-919. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.062 |

| [22] |

付正, 刘伟. PET/CT与功能性MR在骨髓抑制中研究进展[J]. 中国辐射卫生, 2016, 25(5): 636-637, 640. DOI: 10.13491/j.cnki.issn.1004-714X.2016.05.054. Fu Z, Liu W. Advances in PET/CT and functional MR in myelosuppression[J]. Chin J Radiol Health, 2016, 25(5): 636-637, 640. DOI: 10.13491/j.cnki.issn.1004-714X.2016.05.054. (in Chinese) |

| [23] |

Hara JHL, Jutzy JMS, Arya R, et al. Predictors of acute hematologic toxicity in women receiving extended-field chemoradiation for cervical cancer: do known pelvic radiation bone marrow constraints apply[J]. Adv Radiat Oncol, 2022, 7(6): 100998. DOI:10.1016/j.adro.2022.100998 |

| [24] |

Corbeau A, Kuipers SC, de Boer SM, et al. Correlations between bone marrow radiation dose and hematologic toxicity in locally advanced cervical cancer patients receiving chemoradiation with cisplatin: a systematic review[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2021, 164: 128-137. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2021.09.009 |

| [25] |

Yue HZ, Geng JH, Gong LQ, et al. Radiation hematologic toxicity prediction for locally advanced rectal cancer using dosimetric and radiomics features[J]. Med Phys, 2023, 50(8): 4993-5001. DOI:10.1002/mp.16308 |

| [26] |

Le ZY, Wu DM, Chen XM, et al. A radiomics approach for predicting acute hematologic toxicity in patients with cervical or endometrial cancer undergoing external-beam radiotherapy[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2023, 182: 109489. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109489 |

| [27] |

Zhu H, Zakeri K, Vaida F, et al. Longitudinal study of acute haematologic toxicity in cervical cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy[J]. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol, 2015, 59(3): 386-393. DOI:10.1111/1754-9485.12297 |

| [28] |

Rose BS, Aydogan B, Liang Y, et al. Normal tissue complication probability modeling of acute hematologic toxicity in cervical cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2011, 79(3): 800-807. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.11.010 |

| [29] |

Mahantshetty U, Krishnatry R, Chaudhari S, et al. Comparison of 2 contouring methods of bone marrow on CT and correlation with hematological toxicities in non–bone marrow–sparing pelvic intensity-modulated radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin for cervical cancer[J]. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2012, 22(8): 1427-1434. DOI:10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182664b46 |

| [30] |

黄维, 李英, 鲁文力, 等. 宫颈癌同步放化疗中骨盆剂量体积参数与急性骨髓抑制相关因素分析[J]. 中华放射医学与防护杂志, 2016, 36(3): 207-210. Huang W, Li Y, Lu WL, et al. Identification of pelvic dose-volumetric parameters that predict acute bone marrow suppression in concurrent chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer[J]. Chin J Radiol Med Prot, 2016, 36(3): 207-210. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-5098.2016.03.009 |