炎症性肠道疾病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD) 是一组病因不明的慢性非特异性的肠道炎症性疾病, 包含溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC) 和克罗恩病(Crohn's disease, CD)。在北美, UC和CD的发病率在0~19.2/10万和0~20.2/10万之间。在欧洲, UC和CD的发病率在0.6/10万~24.3/10万和0.3/10万~12.7/10万之间[1]。亚洲UC和CD的发病率分别为0.76/10万和0.54/10万, 且近年来呈不断上升趋势[2]。

临床上IBD以内科治疗为主, 常用的治疗药物包括5-氨基水杨酸类、糖皮质激素类和免疫抑制剂等, 但这些药物存在疗效不理想、不良反应多等缺点。目前IBD药物研发的热点主要包括抗肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor, TNF) 单克隆抗体(如阿达木单抗) 等在内的生物制剂, 该类药物较小分子药物更为有效。但生物制剂存在价格昂贵、潜在的免疫排斥反应、储存要求高和应用后耐药等缺点。因此, 研发治疗IBD的药物具有重要意义[3-5]。本文拟通过介绍近年来新颖的IBD药靶及相关药物, 为针对性地开发IBD治疗药物提供思路。

1 经典的IBD治疗药物 1.1 抗炎药物柳氮磺吡啶常用于治疗轻中型IBD, 其主要通过抑制环氧化酶1和2的产生和抗菌作用治疗IBD。但柳氮磺吡啶的不良反应较多, 包括纳差、恶心呕吐、过敏反应、皮疹和肝炎粒细胞减少等。5-氨基水杨酸是一种重要的抗炎药物, 可以通过抑制前列腺素和白三烯的合成从而抑制肠黏膜的炎症, 常用于UC患者的抗炎治疗[6]。但是, 5-氨基水杨酸在改善CD患者临床症状和组织炎症方面收效甚微。5-氨基水杨酸的不良反应与柳氨磺胺吡啶类似, 发生率和严重程度明显减少。但腹泻、药疹、关节炎和瘙痒等比较多见, 且可能对心肌有不良影响[7]。

1.2 免疫抑制药物经典的治疗IBD的免疫抑制药物包括咪唑巯嘌呤[3, 8-11]和6-巯嘌呤、甲氨蝶呤[12]和环孢素A或他克莫司[13]。这类药物主要通过抑制淋巴细胞的增殖和活化发挥免疫抑制作用, 从而改善IBD相关症状。不良反应包括头晕、恶心、呕吐、腹泻、发热、寒战、肌痛、关节痛、肝功能异常、低血压和全身不适等, 咪唑巯嘌呤还可能出现骨髓抑制的严重不良反应。

1.3 以抗TNF药物为主的生物疗法由于一些IBD患者使用经典药物难以起效或者无法耐受经典药物的治疗, 近年来还研发了英夫利昔单克隆抗体、阿达木单克隆抗体、戈里木单克隆抗体等抗TNF药物治疗IBD[3]。但这类生物制剂可能会导致皮疹、血管炎等局部不良反应、条件致病性感染几率增加、血液系统毒性等不良反应, 且仍有许多患者还出现病情未改善或停药后病情加重等现象。统计表明, 30%~50%的IBD患者使用抗TNF疗法后没有效果。

2 治疗IBD的新兴靶点及药物肠黏膜屏障在IBD的发生和发展过程中起到非常重要的作用。肠黏膜屏障的细胞组成成分众多, 包括肠上皮细胞、杯状细胞、潘氏细胞、树突细胞和巨噬细胞等, 这些细胞共同保持着肠腔内容物和黏膜之间的功能平衡。

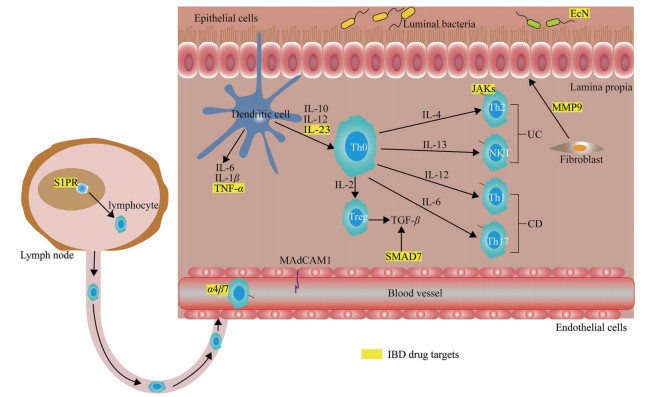

在各种不良因素导致不恰当的免疫激活后, 树突状细胞和其他抗原提呈细胞会启动一系列促炎和抗炎信号, 分泌TNF等细胞因子, 通过淋巴细胞表面受体激活淋巴细胞迁移到炎症效应部位。在迁移过程中, 整合素分子与血管内皮细胞表面表达的细胞黏附分子发生相互作用, 比如整合素α4β7和αEβ7与不同的黏附分子相互作用后, 吸引特异性淋巴细胞。同时, 血管内皮细胞受到炎症刺激后, 自身也会产生各类趋化因子, 将淋巴细胞吸引到肠道炎症部位, 加重肠道炎症。部分治疗IBD的新兴靶点和药物见表 1和图 1。

| Table 1 Emerging therapeutic agents in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). MAdCAM1: Mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1; S1PR: Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor; IL-23: Interleukin-23; S1P: Sphingosine 1-phosphate; JAK: Janus kinase; CHST15: Carbohydrate sulfotransferase 15; PDE4: Phosphodiesterase 4; Smad7: Smad7 protein |

|

Figure 1 Drug targets in IBD, major pathways thought to drive disease pathogenesis and corresponding drug targets are showed in the picture. Dysregulated immune responses driven by a number of complicated factors result in Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Some current and emerging drug targets (shown in yellow). TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; α4β7: α4β7 integrin; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; JAKs: Janus kinases; Th: T helper; NKT: Natural killer T cells; EcN: Escherichia coli Nissle; MMP9: Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

α4β7整合素是特异性地表达于肠道淋巴细胞表面, 它能够与肠道血管中的黏膜地址素细胞黏附分子1 (mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule 1, MAdCAM1) 结合, 从而介导血液中的T细胞进入肠道, 导致或加重肠道局部炎症。研究表明, 通过阻止激活的淋巴细胞迁移至肠道炎症部位可以缓解IBD[14, 15]。抗α4整合素抗体那他珠单抗可通过结合整合素α4的α4β1和α4β7亚单位阻止T细胞归巢到肠道, 该疗法已被用于CD患者的临床试验[16-18]。但是由于该药物可能会引起JC病毒(JCV, 一种人乳头多瘤空泡病毒) 感染, 进而导致进行性多灶性白质脑病, 这一不良反应限制了该药的使用[19]。2014年FDA批准抗α4β7单克隆抗体vedolizumab用于中重度UC和CD, 目前正在开发它的皮下注射剂[20]。Etrolizumab也是一种选择性结合整合素β7的α4β7和αEβ7亚单位的人源化单克隆抗体[21, 22]。在Ⅲ期临床试验中, etrolizumab在诱导期达到主要终点, 但在维持期没有达到主要终点。

2.1.2 鞘氨醇-1-磷脂受体(sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, S1PR) 激动剂在治疗IBD药物的研发中另一个重要进展与鞘氨醇-1-磷脂(S1P) 信号通路有关。S1P可通过与免疫细胞表面的S1PR结合, 诱导淋巴细胞回巢, 抑制淋巴细胞自外周淋巴结的外流, 阻止淋巴细胞到达炎症损害位置。S1PR激动剂能够通过促进淋巴结中的淋巴细胞归巢, 从而导致血液和胸导管淋巴中淋巴细胞减少[23]。有实验证明, S1PR信号通路抑制淋巴细胞的再循环可抑制实验性小鼠结肠炎和结肠炎相关肿瘤的发展[24, 25]。

S1PR受体激动剂奥扎莫得(ozanimod) 已被用于人类UC的临床治疗[24-26]。Ozanimod对S1PR1和S1PR5亲和力较高[27-29], 是一个对S1PR1、S1PR4和S1PR5具有选择性的S1P受体激动剂, 目前正在进行重度UC Ⅲ期以及CD的Ⅱ/Ⅲ期临床试验患者的招募[30]。

同时, 研究者还进行了S1PR激动剂口服治疗IBD的研究。Amiselimod是一个口服的S1P受体激动剂, 它对S1PR选择性较高, 该化合物在日本正在进行一项针对CD的Ⅱ期临床试验[31]。但在一项包括随机、安慰剂对照和180例活动性CD患者的临床试验中, amiselimod未达到主要终点。

2.2 促炎细胞因子和信号通路的阻断剂促炎细胞因子在IBD的发生发展中发挥重要作用, 通过转录因子可以调节促炎细胞因子的表达, 理论上炎性细胞或其调节蛋白也是IBD潜在的治疗靶点[32, 33]。

2.2.1 IL-12和IL-23抑制剂白介素12 (interleukin-12, IL-12) 和IL-23是两种促炎细胞因子, 可在CD患者发炎的黏膜被诱导产生[34]。IL-23是17型辅助T细胞(helper T cell, Th 17) 和三型固有淋巴细胞(innate lymphoid cells 3, ILC3) 通路的调节分子, 这些通路能引起促炎细胞因子和炎症的产生。研究表明, IL-23受体基因的多态性可能与CD的易感性有关[35]。抑制IL-12和IL-23的ustekinumab能有效诱导和维持中重度UC的缓解状态[36, 37]。Mirikizumab是一个能够静脉和皮下注射的单克隆抗体, 它能与IL-23的p19亚基结合[38]。Ⅱ期临床试验表明, mirikizumab有诱导和维持中重度UC缓解状态的趋势[38]。Mirikizumab对CD的治疗目前处于Ⅲ期临床试验。

2.2.2 JAK激酶抑制剂细胞因子信号通路是通过细胞因子与其特定受体结合, 然后磷酸化胞内的酪氨酸蛋白激酶(Janus kinase, JAKs: JAK1、JAK2、JAK3、TYK2) 进而激活下游靶基因的转录和表达。因此, 阻断JAK激酶能够抑制黏膜免疫细胞的细胞因子信号通路。由于单个JAK激酶就能够介导多种促炎细胞因子信号的转导, 所以JAK抑制剂有望同时抑制多种促炎细胞因子的活性[39-42]。非选择性的JAK抑制剂托法替尼于2018年5月被FDA批准用于UC的治疗。临床试验证明, 托法替尼能够诱导和维持临床和内窥镜下UC的症状消退[43]。Filgotinib是一种口服的JAK1选择性小分子抑制剂, 该药物目前正在进行治疗CD的Ⅲ期临床试验。Upadacitinib也是一种JAK1抑制剂, 目前被批准用于甲氨蝶呤无效或不耐受的中度至重度活动量的类风湿关节炎的治疗。TD-1473是一种口服的泛JAK激酶抑制剂, 正在进行中重度CD的Ⅱ期临床试验。

2.2.3 磷酸二酯酶抑制剂及其他磷酸二酯酶(PDE1~PDE11) 是催化环腺苷酸(cAMP) 和环鸟苷酸(cGMP) 分解的胞内酶。PDE4能催化多种细胞中3′5′环腺苷酸的分解, 从而引起NF-κB的激活并最终促进下游的促炎效应。PDE4抑制剂能够增加胞内的cAMP水平, 从而阻断促炎细胞介质的产生, 研究发现阿普斯特(apremilast) 能够抑制干扰素-γ (interferon-γ, IFN-γ)、TNF等促炎细胞因子的产生[44], 这表明PDE4抑制剂能抑制多种细胞因子的产生, 因而具有潜在的治疗IBD活性。

2.3 靶向肠道组织降解和重塑的抑制剂肠黏膜屏障的完整性与基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs) 密切相关。研究表明在IBD患者中, 特别是UC患者中MMP9表达增加。MMP9能够损害结肠上皮通透性和扩大炎症[45], 此外小鼠结肠炎模型中MMP9能够促进血管生成, 并且能够在发炎的肠道中创造一个蛋白水解的环境[46, 47]。目前一个潜在的、高选择性变构MMP9抑制剂(人源化的单克隆抗体GS-5745) 正在进行IBD的临床试验[47]。但由于该药物治疗益处证据不足, 在2016年研发公司终止了GS-5745的Ⅱ/Ⅲ期临床研究[48]。

控制MMPs降解的酶也可调控IBD病变过程中的组织纤维化。肠道纤维化是IBD的并发症之一。以胶原为主的细胞外基质在肠道组织的过度合成以及异常沉积可导致肠道纤维化, 延缓肠道纤维化可改善IBD的自然病程。碳水化合物磺基转移酶15 (carbohydrate sulfotransferase 15, CHST15) 是一种特异性合成硫酸软骨素E的酶, 硫酸软骨素E能够与多种致病介质结合并促进组织纤维化。有研究证明, 在葡聚糖硫酸钠(dextran sulfate sodium, DSS) 诱导的急性结肠炎中, 基于小干扰RNA (siRNA) 沉默CHST15能降低结肠炎活动性并减少肠道巨噬细胞和成纤维细胞的累积。在慢性DSS诱导的结肠炎中, CHST15的siRNA能降低结肠炎的活动性和α-平滑肌肌动蛋白(α-SMA) 阳性的成纤维细胞和胶原沉积。STNM01是另外一个人工合成的抗CHST15双链RNA药物。2016年的一项Ⅰ期CD临床研究已证明该化合物的安全性[49]。接受STNM01治疗的大部分患者与安慰剂组相比都有明显的内镜下炎症减少, 此外, 组织学分析表明STNM01能够减少CD患者中的组织纤维化。

转化生长因子β (transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β) 对细胞的生长、分化和免疫功能都有重要的调节作用, 它可以调节炎症和组织纤维化过程, 尤其是在肠道。它的抗炎活性会受到Smad7蛋白的抑制[50, 51]。有研究表明在实验性结肠炎中, 阻断Smad7的表达能够增强TGF-β信号通路从而改善结肠炎。CD患者体内的肠道炎症伴随TGF-β含量的下降, 这是由于胞内Smad7蛋白增加引起的[52]。Mongersen是一种能特异性结合Smad7的信使RNA的口服反义寡核苷酸药物, 它能阻止Smad7的表达, 从而上调TGF-β1信号通路。一项针对CD患者的Ⅱ期临床研究表明Mongersen的临床结果明显优于安慰剂组[53], 但是在中期分析后该药物的Ⅲ期临床试验被终止了, 尚并不清楚该类药物是否进行进一步的研发。

2.4 其他靶点的药物和疗法大肠杆菌尼斯勒(Escherichia coli Nissle, EcN) 是一种能控制肠屏障功能和诱导抗炎蛋白表达的非致病性革兰阴性杆菌[54, 55]。目前EcN被认为可用于治疗UC, 其机制与5-氨基水杨酸的抗炎作用相似[55]。EcN具有直接的抗细菌作用, 控制生物膜的形成, 刺激人肠上皮细胞β-防御素的产生并且通过上调闭锁蛋白增强紧密连接[55]。除此之外, 粪菌移植也被考虑用于IBD的治疗[56], 一项UC患者中进行的随机对照临床试验证明粪菌移植每周1次, 持续6周患者的缓解率显著高于安慰剂组[56], 该疗法的安全性和疗效还需要进一步的验证。

3 总结与展望已有的IBD治疗药物能够显著改善IBD的疾病过程, 但这些药物都有不足之处。基于IBD动物模型研究、基因研究、IBD患者的临床组织和病例分析以及对其他慢性炎症疾病中炎症途径的深入研究, 目前许多新的治疗方法及靶向药物包括新的细胞因子和信号传导阻滞剂已经被开发并应用于IBD临床研究中。如JAK抑制剂和S1PR调节剂等小分子药物的研究有了很大进展。该类化合物合成简单、给药方便、依从性好, 且无免疫原性。其中一些药物有望获得FDA或欧洲药品管理局的批准, 可能能使IBD的治疗达到一个新的终点[57, 58], 包括内镜下黏膜愈合、深度缓解(临床缓解+黏膜愈合)、透壁愈合和组织学愈合等指标。

总之, 随着IBD基础研究的不断深入, IBD的治疗靶点也在不断增加, 针对IBD发病机制中不同的炎症通路的新治疗药物将很快用于IBD的治疗, IBD治疗的下个目标可能是根据不同的生物标志物和患者状况, 选择相应作用机制的治疗药物, 增加IBD治疗的个性化。

作者贡献: 柴常伟负责全文的撰写; 张翼翔负责文章的核对和格式修改; 张海婧和吴练秋对论文进行整体的指导和修改。

利益冲突: 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Park J, Cheon JH. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease across Asia[J]. Yonsei Med J, 2021, 62: 99-108. DOI:10.3349/ymj.2021.62.2.99 |

| [2] |

Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 12: 205-217. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.34 |

| [3] |

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362: 1383-1395. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0904492 |

| [4] |

Colombel JF, Rutgeerts PJ, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab induces deep remission in patients with Crohn's disease[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 12: 414-422.e5. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.019 |

| [5] |

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 369: 711-721. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1215739 |

| [6] |

Allgayer H. Review article: mechanisms of action of mesalazine in preventing colorectal carcinoma in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2003, 18 Suppl 2: 10-14. |

| [7] |

Lim WC, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, et al. Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn's disease[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016, 7: CD008870. |

| [8] |

Atreya I, Diall A, Dvorsky R, et al. Designer thiopurine-analogues for optimised immunosuppression in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2016, 10: 1132-1143. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw091 |

| [9] |

D'Haens G, Geboes K, Ponette E, et al. Healing of severe recurrent ileitis with azathioprine therapy in patients with Crohn's disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 1997, 112: 1475-1481. DOI:10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70027-1 |

| [10] |

Oancea I, Movva R, Das I, et al. Colonic microbiota can promote rapid local improvement of murine colitis by thioguanine independently of T lymphocytes and host metabolism[J]. Gut, 2017, 66: 59-69. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310874 |

| [11] |

Tiede I, Fritz G, Strand S, et al. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes[J]. J Clin Invest, 2003, 111: 1133-1145. DOI:10.1172/JCI16432 |

| [12] |

Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators[J]. N Engl J Med, 2000, 342: 1627-1632. DOI:10.1056/NEJM200006013422202 |

| [13] |

Feuerstein JD, Akbari M, Tapper EB, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of third-line salvage therapy with infliximab or cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis[J]. Ann Gastroenterol, 2016, 29: 341-347. |

| [14] |

Podolsky DK, Lobb R, King N, et al. Attenuation of colitis in the cotton-top tamarin by anti-alpha 4 integrin monoclonal antibody[J]. J Clin Invest, 1993, 92: 372-380. DOI:10.1172/JCI116575 |

| [15] |

Picarella D, Hurlbut P, Rottman J, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for beta 7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) reduce inflammation in the colon of scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells[J]. J Immunol, 1997, 158: 2099-2106. |

| [16] |

Ghosh S, Goldin E, Gordon FH, et al. Natalizumab for active Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2003, 348: 24-32. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa020732 |

| [17] |

Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Enns R, et al. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 353: 1912-1925. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa043335 |

| [18] |

Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: results of the ENCORE trial[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 132: 1672-1683. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.024 |

| [19] |

Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. Progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 353: 362-368. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa051586 |

| [20] |

Al-Bawardy B, Shivashankar R, Proctor DD. Novel and emerging therapies for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2021, 12: 651415. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2021.651415 |

| [21] |

Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Tyrrell H, et al. Etrolizumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: an overview of the phase 3 clinical program[J]. Adv Ther, 2020, 37: 3417-3431. DOI:10.1007/s12325-020-01366-2 |

| [22] |

Vermeire S, O'Byrne S, Keir M, et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet, 2014, 384: 309-318. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60661-9 |

| [23] |

Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Brown S, Studer SM, et al. S1P signaling: new therapies and opportunities[J]. F1000Prime Rep, 2014, 6: 109. |

| [24] |

Snider AJ, Kawamori T, Bradshaw SG, et al. A role for sphingosine kinase 1 in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis[J]. FASEB J, 2009, 23: 143-152. DOI:10.1096/fj.08-118109 |

| [25] |

Deguchi Y, Andoh A, Yagi Y, et al. The S1P receptor modulator FTY720 prevents the development of experimental colitis in mice[J]. Oncol Rep, 2006, 16: 699-703. |

| [26] |

Degagné E, Saba JD. S1pping fire: sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling as an emerging target in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated cancer[J]. Clin Exp Gastroenterol, 2014, 7: 205-214. |

| [27] |

Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2016, 15: 373-381. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00018-1 |

| [28] |

Cohen JA, Comi G, Selmaj KW, et al. Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a multicentre, randomised, 24-month, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2019, 18: 1021-1033. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30238-8 |

| [29] |

Comi G, Kappos L, Selmaj KW, et al. Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (SUNBEAM): a multicentre, randomised, minimum 12-month, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2019, 18: 1009-1020. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30239-X |

| [30] |

Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Zhang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of etrasimod in a phase 2 randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158: 550-561. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.035 |

| [31] |

Perez-Jeldres T, Alvarez-Lobos M, Rivera-Nieves J. Targeting sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in immune-mediated diseases: beyond multiple sclerosis[J]. Drugs, 2021, 81: 985-1002. DOI:10.1007/s40265-021-01528-8 |

| [32] |

Popp V, Gerlach K, Mott S, et al. Rectal delivery of a DNAzyme that specifically blocks the transcription factor GATA3 and reduces colitis in mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152: 176-192.e5. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.005 |

| [33] |

Withers DR, Hepworth MR, Wang X, et al. Transient inhibition of ROR-γt therapeutically limits intestinal inflammation by reducing TH17 cells and preserving group 3 innate lymphoid cells[J]. Nat Med, 2016, 22: 319-323. DOI:10.1038/nm.4046 |

| [34] |

Fuss IJ, Becker C, Yang Z, et al. Both IL-12p70 and IL-23 are synthesized during active Crohn's disease and are down-regu-lated by treatment with anti-IL-12 p40 monoclonal antibody[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2006, 12: 9-15. DOI:10.1097/01.MIB.0000194183.92671.b6 |

| [35] |

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389: 1699-1709. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30570-6 |

| [36] |

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375: 1946-1960. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1602773 |

| [37] |

Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381: 1201-1214. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1900750 |

| [38] |

Sandborn WJ, Ferrante M, Bhandari BR, et al. Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with ulcerative colitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2020, 158: 537-549.e10. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.043 |

| [39] |

Boland BS, Sandborn WJ, Chang JT. Update on Janus kinase antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2014, 43: 603-617. DOI:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.011 |

| [40] |

Gerlach K, Hwang Y, Nikolaev A, et al. TH9 cells that express the transcription factor PU. 1 drive T cell-mediated colitis via IL-9 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Nat Immunol, 2014, 15: 676-686. DOI:10.1038/ni.2920 |

| [41] |

Monteleone G, Monteleone I, Fina D, et al. Interleukin-21 enhances T-helper cell type Ⅰ signaling and interferon-gamma production in Crohn's disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 2005, 128: 687-694. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.042 |

| [42] |

Shinohara T, Nemoto Y, Kanai T, et al. Upregulated IL-7 receptor α expression on colitogenic memory CD4+ T cells may parti-cipate in the development and persistence of chronic colitis[J]. J Immunol, 2011, 186: 2623-2632. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1000057 |

| [43] |

Sandborn WJ, Su C, Panes J. Tofacitinib as induction and main-tenance therapy for ulcerative colitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377: 496-497. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1707500 |

| [44] |

Mazur M, Karczewski J, Lodyga M, et al. Inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE 4): a new therapeutic option in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis[J]. J Dermatolog Treat, 2014, 26: 326-328. |

| [45] |

Nighot P, Al-Sadi R, Rawat M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability contributes to the severity of experimental DSS colitis[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2015, 309: G988-G997. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00256.2015 |

| [46] |

Matusiewicz M, Neubauer K, Mierzchala-Pasierb M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: its interplay with angiogenic factors in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Dis Markers, 2014, 2014: 643645. |

| [47] |

Marshall DC, Lyman SK, McCauley S, et al. Selective allosteric inhibition of MMP9 is efficacious in preclinical models of ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10: e0127063. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0127063 |

| [48] |

Sandborn WJ, Bhandari BR, Randall C, et al. Andecaliximab [anti-matrix Metalloproteinase-9] induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 study in patients with moderate to severe disease[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2018, 12: 1021-1029. |

| [49] |

Suzuki K, Yokoyama J, Kawauchi Y, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of siRNA targeting carbohydrate sulphotransferase 15 in Crohn's disease patients with active mucosal lesions[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2017, 11: 221-228. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw143 |

| [50] |

Yan X, Liu Z, Chen Y. Regulation of TGF-beta signaling by Smad7[J]. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin, 2009, 41: 263-272. DOI:10.1093/abbs/gmp018 |

| [51] |

Briones-Orta MA, Tecalco-Cruz AC, Sosa-Garrocho M, et al. Inhibitory Smad7: emerging roles in health and disease[J]. Curr Mol Pharmacol, 2011, 4: 141-153. DOI:10.2174/1874467211104020141 |

| [52] |

Monteleone G, Neurath MF, Ardizzone S, et al. Mongersen, an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide, and Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372: 1104-1113. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1407250 |

| [53] |

Monteleone G, Pallone F. Mongersen, an oral SMAD 7 antisense oligonucleotide, and Crohn's disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372: 2461. DOI:10.1056/NEJMc1504845 |

| [54] |

Lasaro MA, Salinger N, Zhang J, et al. F1C fimbriae play an important role in biofilm formation and intestinal colonization by the Escherichia coli commensal strain Nissle 1917[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2009, 75: 246-251. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01144-08 |

| [55] |

Scaldaferri F, Gerardi V, Mangiola F, et al. Role and mechanisms of action of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in the maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis patients: an update[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22: 5505-5511. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i24.5505 |

| [56] |

Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 149: 110-118.e4. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.045 |

| [57] |

Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review[J]. Gut, 2012, 61: 1619-1635. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830 |

| [58] |

Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts cortico-steroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up[J]. Gut, 2016, 65: 408-414. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309598 |

2022, Vol. 57

2022, Vol. 57