炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD) 是一种以消化道溃疡为显著特点的慢性自身免疫疾病[1]。近些年世界各地其发病率成倍增加[2, 3], 患者长期遭受消化道出血、穿孔、肠梗阻等病痛的折磨。IBD主要包括溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC) 和克罗恩病(Crohn's disease, CD)。对于病变位置, UC在结直肠, 一般呈连续的弥漫性分布, 大多数在乙状结肠和直肠, 可累及横结肠及降结肠, 甚至扩展至全结肠[4], 炎症仅限于黏膜和黏膜下层, 并伴有隐膜炎和隐窝脓肿[5]; CD的病变在胃肠道的任意位置, 且可以不连续[6], 在组织学上表现为黏膜下层增厚、透壁炎症、溃疡裂和肉芽肿[5]。

肠黏膜愈合被认为是治疗IBD的核心, 但目前临床用药不能实现IBD患者的完整黏膜愈合。在肠黏膜修复过程中, 巨噬细胞与多种肠道上皮细胞通过密切的胞间交互对话, 直接促进其增殖分化或创造出有利于上皮再生和黏膜愈合的微环境, 是实现修复不可或缺的参与者, 而IBD患者消化道内异常的巨噬细胞也是其自身黏膜修复出现障碍的关键之一[7]。基于此, 本综述通过文献查阅及总结, 明确调控巨噬细胞对于IBD患者肠黏膜愈合的重要性, 并总结其中具有代表性的治疗靶点, 以期为未来IBD的治疗提供方向。

1 促进肠黏膜愈合的必要性以及目前疗法的不足 1.1 促进肠黏膜愈合在IBD治疗中的意义肠黏膜的愈合是IBD公认的治疗目标[8-10]。肠黏膜愈合能够明确改变IBD病程, 持续缓解临床症状, 显著改善临床结果以及降低患者的住院率和手术切除率。这就是为什么即使黏膜愈合可能不会根治IBD, 也被认为是CD和UC的治疗目标和临床试验的终点[11]。一项对于CD患者的临床分析表明, 使用英夫利息单抗达到肠黏膜愈合的患者, 在停药后14~78周内没有出现临床复发, 相比之下, 没有肠黏膜愈合的患者在0~8周内相继出现临床复发[1]。对于UC也有类似的结果, 相较于黏膜愈合的患者, 82例临床缓解但仍有黏膜炎症的患者在1年内复发风险增加了2~3倍[1]。肠黏膜愈合还能降低患者住院率和手术切除率。达到黏膜愈合的UC患者1年内结肠切除率仅为2% (3/178), 5年内结肠切除率为7% (13/176)[12]。达到黏膜愈合的CD患者5年内进行手术的概率为11% (6/53), 而未能愈合的患者1年内手术率为20% (18/88)[12]。因此, 实现肠黏膜愈合意味着患者大概率预后良好、长期缓解。

手术多为IBD患者药物治疗失败时的选择, 且术后的并发症以及疾病复发率较高[1]。对于UC而言, 患者手术后近期吻合口瘘和腹腔脓肿发生率为4.3%和7.5%。559例UC手术患者中, 术后90天并发症发生率为33.3%, 其中, 肠道相关并发症为59.7%, 感染性并发症为34.4%, 切口相关并发症为24.7%[13]。CD的手术治疗是在药物治疗失败时为缓解症状或为了治疗并发症所采取的治疗方法, 极少是治愈性的, 术后疾病常复发[14]。CD患者的回肠结肠切除后腹腔内感染性并发症(intra-abdominal septic complications, IASC) 很常见, 一项回顾性试验分析, 6年内CD患者术后30天IASC的发生率为9.7%, 如果患者在手术前用皮质激素并伴有腹腔内脓肿, 术后IASC的发生率为40%[15]; 2 638例CD手术患者中, 术后90天内并发症发生率为23.8%, 其中, 肠道相关并发症为63.2%, 感染性并发症为33.9%, 切口相关并发症为19.9%[16]。CD患者10年后初次切除复发再次切除的累积概率为30%~44%[15]。由此看出, 手术是疾病进展到一定阶段的妥协治疗手段, 对于缓解患者长期身体痛苦作用有限。

综上所述, 促进IBD患者肠黏膜愈合能明显改善疾病进程, 减少疾病复发, 且相较于手术切除, 通过促进肠黏膜愈合实现IBD患者疾病的长期缓解能免除患者遭受手术后并发症的困扰, 更能提高患者的生活质量。

1.2 目前临床用药现状: 重点抗炎不能促进完全的肠黏膜愈合目前治疗IBD的一线用药仍然以抗炎为主。根据世界胃肠病组织推荐的IBD全球实践指南(2015年) 和中华医学会推荐的《炎症性肠病诊断与治疗的共识意见》 (2018年, 北京)[14, 17], 临床用药共有6类: 氨基水杨酸类、糖皮质激素类、免疫调节剂类、生物抑制剂类、抗生素类和益生菌。

除抗生素类和益生菌之外, 其他4类药物均以抗炎为主[18], 但这些药物对于促进肠黏膜愈合, 治疗IBD疗效有限, 尤其对于中重度的IBD患者, 目前临床约50%的中度至重度IBD患者不能达到黏膜愈合。一项CD临床试验表明, 即使抗肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor, TNF) 单抗和硫唑嘌呤药物联用, 并在生物标志物(粪便钙卫蛋白和C反应蛋白) 的指导下进行早期积极药物治疗, 48周后, 患者内镜黏膜愈合比例仍低于50%, 在同一研究的常规治疗组中这一比率更低, 仅为30%。2017~2019年UC进行的3项临床试验, 内窥镜下显示黏膜改善率分别为39.7%、27.7%和51.1% (使用药物分别为维多珠单抗、阿达木单抗和尤特克单抗)[19]。并且这些药物高发的不良反应和药物失效也给临床治疗带来极大困扰[18]。此外, IBD患者体内具有促炎特性的细菌菌株增多, 如变形杆菌、黏附性侵染性大肠杆菌和梭状芽孢杆菌, 相比之下, 能引起抗炎反应的细菌, 如克氏梭菌和费氏杆菌等细菌减少了, 而CD患者常用的抗生素辅助治疗会增加微生物的病害[20]。

目前, 主流的抗炎药物不能促进完全的肠黏膜愈合, 对于IBD疗效有限, 总结原因有3点: ①仅为对症治疗。持续炎症只是IBD疾病的表观异常, 而IBD患者自身相关机制或细胞功能的异常则可能是疾病发生的根本原因, 故仅针对炎症的治疗无法改变疾病的本质; ②治疗靶点单一。目前临床用药除益生菌类药物外, 其余5类药物作用靶点较为单一, 不能从多通路多靶点同时纠正或改善IBD的病理变化。但IBD是多因素共同作用的系统性疾病[5], 肠道内多个靶点均出现了异常, 故使用靶点单一的药物定会疗效欠佳; ③不良反应多发。目前临床所用化学药物, 一味针对某一靶点的激动或抑制, 容易导致机体与该靶点相关的生物学功能发生改变, 进而导致不良反应的发生[4]。因此, 当前这种重点靶向抗炎的治疗不能促进肠黏膜愈合, 改变IBD疾病进程。

2 巨噬细胞是促IBD患者肠黏膜再生的有效靶点当肠道上皮屏障受损后, 巨噬细胞对于重建肠上皮屏障必不可少[7]。研究表明, 葡聚糖硫酸钠(dextran sodium sulfate, DSS) 可损害结肠黏膜细胞之间连接引发结肠炎[21], 而经DSS处理过后的小鼠肠道破损处巨噬细胞聚集, 巨噬细胞集落刺激因子-1 (macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1, CSF-1) 缺乏的小鼠其肠道上皮屏障破坏后无法募集单核细胞, 其结肠上皮祖细胞也因此无法进行正常肠上皮损伤修复[22]。IBD患者体内异常的巨噬细胞影响了正常的修复过程。

2.1 肠道巨噬细胞在正常稳态环境中促进肠黏膜再生炎症早期, 大量中性粒细胞进入组织, 单核细胞也被募集而来, 分化为炎性巨噬细胞, 表现为促炎作用, 对抗原产生适当的免疫反应。随后, 中性粒细胞吞噬杀菌后随即凋亡, 炎症进入消退阶段。而巨噬细胞专门检测和吞噬凋亡的中性粒细胞, 以防继发性坏死和炎症的进一步加剧。巨噬细胞经“find me”信号(如溶血磷脂酰胆碱、鞘氨醇1-磷酸、趋化因子CX3CL1等) 被引导至凋亡细胞附近, 通过“eat me”信号(如膜联蛋白-1、磷脂酰丝氨酸) 吞噬凋亡细胞, 而通过“don't eat me”抑制信号保护活细胞。一旦巨噬细胞经胞葬作用, 其表型发生转化, 多转变为消炎表型M2型[7], 使巨噬细胞主要发挥促进炎症消散和组织修复再生的作用: 第一, 经胞葬作用后, 巨噬细胞核受体激活, 使其通过旁分泌或自分泌抗炎介质来维持和促进抗炎反应[23], 如产生转化生长因子-β (transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β)、白细胞介素(interleukin, IL)-10等抗炎细胞因子并抑制核因子κB (nuclear factor kappa-B, NF-κB) 等促炎信号[24]; 第二, 胞葬信号联合M2型巨噬细胞诱导信号激活的巨噬细胞, 能将再生信号传递至邻近的结肠上皮祖细胞, 促进损伤后上皮的愈合[22], 如M2型巨噬细胞产生的精氨酸酶1 (arginase-1, Arg-1) 可将L-精氨酸转化成多胺, 多胺通过c-Myc和p21分子促进附近隐窝中肠道干细胞增殖分裂, 参与伤口愈合[25], 且此过程依赖于TAM受体酪氨酸激酶受体家族中Axl/Mertk受体胞葬信号[26]; 第三, 巨噬细胞通过改变其代谢和激活大量的吞噬受体等方式[24], 增加MertK、Axl、CD36等受体分子转录, 进一步强化、延长胞葬作用[23, 24]。由此可以看出, 在正常的肠道环境中, 具有特定促进肠黏膜修复的巨噬细胞为M2型巨噬细胞[27], 且胞葬作用与巨噬细胞促进修复信号表达紧密相关[28, 29]。

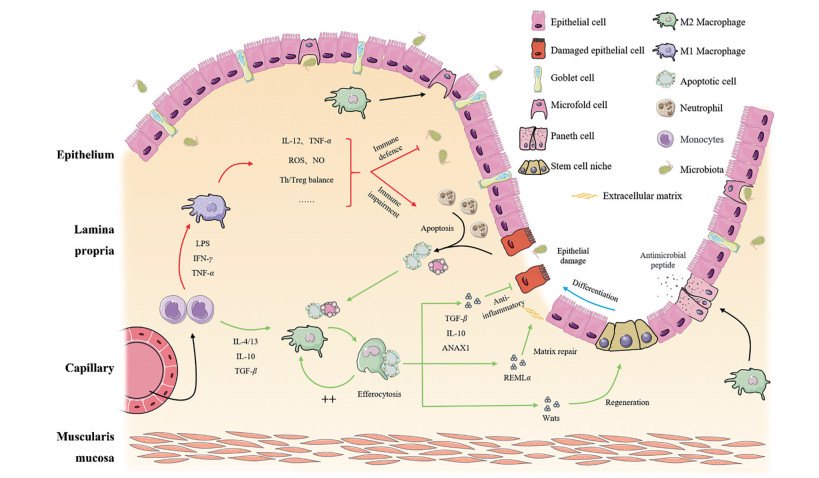

除直接促进肠道干细胞再生外, 巨噬细胞辅助其他细胞功能以维持肠上皮屏障完整的作用也不容忽视, 研究表明, 如阻断单核细胞向巨噬细胞的分化、Paneth细胞产生抗菌肽能力减弱、富含亮氨酸重复序列的G蛋白偶联受体5阳性(leucine rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5+, Lgr5+) 肠道干细胞和M细胞的分化均受到影响[30], 这更加表明巨噬细胞在肠道内修复微环境中多靶点的复杂作用和不可或缺的重要地位(图 1)。

|

Figure 1 Multiple targets of macrophage in regulating inflammation and promoting mucosal healing. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; IFN-γ: Interferon gamma; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-4/13: Interleukin-4/13; IL-10: Interleukin-10; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-beta; IL-12: Interleukin-12; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; NO: Nitric oxide; ANXA1: Annexin A1; Relmα: Resistin-like molecule alpha; WNTs: Wnt signaling pathway. Some elements of this figure were adapted from Servier Medical Art (http://smart.servier.com/), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unsupported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) |

IBD患者表现出明显的促炎巨噬细胞增多, 且巨噬细胞的胞葬作用和其他细胞的联系均出现异常。单核细胞和促炎性M1巨噬细胞在IBD患者固有层中明显增加。侵入肠组织的固有层单核细胞和M1巨噬细胞通过破坏紧密连接蛋白和诱导上皮细胞凋亡直接促进上皮屏障破坏, 从而驱动IBD肠道炎症[31]。目前, 与IBD相关的至少163个易感基因位点已经确定[32], 而吞噬凋亡小肠上皮细胞的肠道巨噬细胞过表达的基因与IBD的41个易感基因重叠, 如IL-12B、淋巴细胞特异性蛋白1 (lymphocyte-specific protein 1, LSP1) 等基因, 这一事实表明, 巨噬细胞胞葬能力下降与IBD发病关联紧密[7]。另外, Paneth细胞功能异常在CD患者中很明显, 并且可能是单核细胞对Wnt-配体刺激不足的结果[30]。

综上所述, 由于IBD患者自身基因、环境等因素以及长期受炎症环境的影响, 患者自身肠道内, 以巨噬细胞为代表的黏膜修复过程或相关细胞机制出现异常, 故单纯的抑制炎症不可能实现良好的肠黏膜愈合, 而调控异常机制使其恢复正常稳态的生理过程则是当下之需。

3 基于调节巨噬细胞具有促进肠黏膜愈合潜在活性的药物及靶点针对第二部分提到的异常, 国内外研究者都进行了广泛的探索。西医药能够精准地靶向治疗, 改变细胞的异常功能或细胞间的联系, 以促进IBD患者肠黏膜愈合[33]; 而中医药具有抗炎、黏膜修复和免疫调节多靶点药效同时进行的优势。另外, 长期经年的使用, 使得中药用法与剂量易于调控, 不良反应相对较低。因此中西医在促进肠黏膜修复、治疗IBD方面都具有独特的优势。

3.1 西医药基于巨噬细胞调节促进肠黏膜愈合首先, 直接靶向巨噬细胞极化, 促进M2型巨噬细胞产生。IL-4作用于巨噬细胞的主要功能是使巨噬细胞极化为替代激活巨噬细胞[34]。IL-4激活的巨噬细胞可以修复肠黏膜, 减轻结肠炎炎症。IL-4可通过激活巨噬细胞中信号传导及转录激活蛋白6 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 6, STAT6) 促进肠道组织修复[35]。经IL-4处理的小鼠腹腔巨噬细胞以STAT6分子依赖的方式过表达Wnt2b、Wnt7b和Wnt10a, 激活Wnt信号通路促进2, 4, 6-三硝基苯磺酸(2, 4, 6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid, TNBS) 处理的小鼠的黏膜修复[36]。体内外实验证明, 经IL-4处理的巨噬细胞能促进上皮细胞伤口修复[37], 且经冷冻保存后仍有抗结肠炎的作用[38]。第二, 靶向巨噬细胞胞葬, IL-4起到组织修复作用依赖于巨噬细胞胞葬信号Axl/Mertk, 故巨噬细胞Axl/Mertk可能是起治疗作用的潜在靶点[26, 39]。第三, 靶向单核细胞/巨噬细胞与其他细胞的关系, 缺乏CSF-1的小鼠单核细胞不能正常分化为巨噬细胞, 同时, 小鼠肠隐窝内Paneth细胞、Lgr5+肠干细胞和M细胞正常功能均受到影响, 表明CSF1具有在损伤、炎症或化学疗法后恢复上皮功能的潜力, 且这种作用已在其他器官中得到证实[30]。除以上所写之外, 表 1[19, 25, 35, 37, 39-49]详细列出了一些药物或方法及其作用靶点。

| Table 1 Examples of methods/drugs that promote mucosal repair and relative targets. CCR2: CC chemokine receptor-2; DSS: Dextran sodium sulfate; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; TNBS: 2, 4, 6-Trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; Trem2: Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; TLR9: Toll-like receptor 9; LXA4: Lipoxin A4; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor |

大量研究表明, 中医药对于IBD肠黏膜愈合有良好作用。中医认为IBD病机复杂, 总属本虚标实, 虚为正气不足, 脾肾两虚, 机体免疫力低下; 实为毒邪久伏体内蕴结肠道, 使免疫系统异常, 炎症反应亢进, 损伤肠黏膜屏障, 本虚标实相互为害, 共同参与疾病的发生、发展过程[50]。故治疗IBD, 中医多补泻兼施、清温并用, 以解伏毒, 补脾肾为根本[51]。许多方药对于“巨噬细胞-肠黏膜修复”这一整合单元具有潜在的调控作用, 如常用的清热类和补益类方药, 多从调节免疫微环境和黏膜修复保护角度进行治疗。

在调节免疫微环境方面, 清热类方药效果突出。以巨噬细胞为代表, 黄连中的小檗碱可以抑制DSS模型小鼠的结肠巨噬细胞产生促炎细胞因子, 抑制其促炎功能, 并促进结肠中巨噬细胞凋亡, 促进DSS诱导的小鼠结肠炎的恢复[52]。黄芩苷可以上调干扰素因子4蛋白的表达并能逆转脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS) 诱导的巨噬细胞激活, 通过调节巨噬细胞极化, 从而改善DSS诱导的结肠炎小鼠的炎症反应[53]。对于复方的使用, 王永强等[54]使用溃结2号方(包括黄芪、太子参、白术、生地、鸡眼草、地锦草、桃仁、川芎), 可以降低M1型巨噬细胞水平, 从而达到促进溃疡性结肠炎创面愈合的作用, 且长时间用药较短期治疗具有明显优势。针对免疫微环境的调节, 目前中医药对其机制研究尚浅, 仍以抗炎保护为重点, 较少关注免疫细胞对肠黏膜修复的直接促进作用。

在促进肠黏膜再生修复中, 补益类方药具有潜在的功能。如黄芪中黄芪多糖通过降低UC模型大鼠结肠组织中的髓过氧化物酶(myeloperoxidase, MPO) 活性及肿瘤坏死因子α (tumor necrosis factor alpha, TNF-α) 含量减轻肠道炎症反应, 从而减轻黏膜损伤[55, 56]。四君子汤是健脾益气的经典方剂, 对于肠黏膜修复有良好作用, 研究表明, 其可通过维持肠上皮细胞的紧密连接以修复肠黏膜的机械屏障、促进杯状细胞分泌黏蛋白以修复肠黏膜的化学屏障[57]、抑制派伊尔结细胞的凋亡以修复肠黏膜的免疫屏障[58]、提高肠道优势菌群的数量以修复肠黏膜的生物屏障[59]。但对于补益方药通过调控免疫系统以实现炎性修复鲜有研究。

除上述实例外, 表 2[4, 55, 56, 60-75]详细列出了治疗IBD常用的中药、有效成分及靶点, 突出中医药用药特色和当前研究的局限性。

| Table 2 Examples of traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of IBD and its potential targets |

生理状态下, 免疫细胞与肠黏膜“损伤-愈合”平衡息息相关, 以维系肠道黏膜屏障稳态。针对IBD的治疗, 靶向免疫细胞不仅促进了炎症消散, 还能够在功能水平上使异常的肠上皮细胞趋向正常。以巨噬细胞为例, IL-4促进肠道黏膜修复依赖于巨噬细胞胞葬[39]; 巨噬细胞中Wnt信号通路对于激活肠道干细胞, 促进肠隐窝再生是不可或缺的[36, 76, 77]; 正常巨噬细胞对于Paneth细胞产生抗菌肽、M细胞的分化也必不可少[30]。

其他器官的修复与巨噬细胞也密切相关。腹腔中成熟的巨噬细胞在出现损伤时, 能够直接进入内脏器官中的损伤位点, 从而立即启动快速修复过程[78]。并且越来越多的研究表明, 以巨噬细胞表型及胞葬功能为靶点的治疗对修复愈合具有促进作用。如糖尿病模型小鼠其创面巨噬细胞存在从促炎型到修复型的表型转化障碍[79]。在修复后期创面周围聚集大量的巨噬细胞, 诱导型一氧化氮合酶(inducible nitric-oxide synthase, iNOS) 高表达, Arg-1低表达, 而去除创面中M1型巨噬细胞, 能够启动糖尿病小鼠难愈创面的快速上皮化的过程, 促进创面愈合[80]。阻断巨噬细胞Axl和Mertk胞葬信号后, 肺损伤小鼠肺伤口愈合迟缓, 修复不良[39]。因此, 通过干预巨噬细胞表型转化及胞葬功能, 进而促进慢性创面的愈合, 将成为研究和临床治疗的有效手段。

中医药治疗IBD患者肠黏膜愈合效果明显, 且具有靶点多、安全性高的优势, 是开发治疗IBD药物的巨大宝库。如青黛中含有芳烃受体的配体, 可诱导IL-22的产生以介导黏膜的再生, 促进UC患者的黏膜愈合[81], 已广泛作为临床抗结肠炎的治疗药物。此外, 青黛还对类固醇依赖的UC患者和使用过抗TNF-α的患者也有治疗作用, 能够显著提高患者临床反应率和黏膜愈合率, 降低粪便钙卫蛋白水平[82]。虽然中医药研究越来越重视免疫微环境调节和促肠黏膜修复, 如清热类和补益类方药对于“巨噬细胞-肠黏膜修复”这一整合单元中关键环节有潜在的调控价值, 但目前多数研究都是从简单的抗炎角度去实现组织损伤的保护, 或从直接的修复再生角度去实现肠黏膜修复, 对依据完整的通路链条去实现组织再生关注不足。综上所述, 未来应该立足于炎性修复的全链条去关注药物的治疗策略, 才能真正发挥以M2型巨噬细胞为代表的、与组织再生修复有关的免疫细胞在炎症损伤性疾病中的关键作用, 也凸显出中医药“扶正祛邪”理论的科学性和优效性。

作者贡献: 杜欣珂负责选题、图表制作和文章撰写; 冉庆森和刘丽负责文章的撰写和修改; 孙立东、杨庆、李玉洁和陈颖参与文章的修改并检查图表内容; 朱晓新研究员对稿件整体内容进行指导和修改; 李琦副研究员负责文章的选题和思路, 提出框架及文章的修改, 为该文章的主要负责人。所有作者批阅并准许了最终稿件。

利益冲突: 所有作者均声明本论文与其他人或机构无任何利益冲突。

| [1] |

Pineton DCG, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lemann M, et al. Clinical implications of mucosal healing for the management of IBD[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010, 7: 15-29. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2009.203 |

| [2] |

Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Translating immunology into therapeutic concepts for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2018, 36: 755-781. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053055 |

| [3] |

Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: east meets west[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020, 35: 380-389. DOI:10.1111/jgh.14872 |

| [4] |

Heng Y. Investigation for the Effects and Mechanism of Glycyrrhizin on Tight Junctional Protein to Repair the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Injury with Ulcerative Colitis (甘草酸调节紧密连接蛋白修复溃疡性结肠炎肠黏膜屏障损伤的药理作用研究)[D]. Xi'an: Fourth Military Medical University, 2017.

|

| [5] |

Guan Q. A comprehensive review and update on the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. J Immunol Res, 2019, 2019: 7247238. |

| [6] |

Roda G, Chien Ng S, Kotze PG, et al. Crohn's disease[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2020, 6: 22. DOI:10.1038/s41572-020-0156-2 |

| [7] |

Na YR, Stakenborg M, Seok SH, et al. Macrophages in intestinal inflammation and resolution: a potential therapeutic target in IBD[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16: 531-543. DOI:10.1038/s41575-019-0172-4 |

| [8] |

Hine AM, Loke PN. Intestinal macrophages in resolving inflammation[J]. J Immunol, 2019, 203: 593-599. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1900345 |

| [9] |

Graham WV, He W, Marchiando AM, et al. Intracellular MLCK1 diversion reverses barrier loss to restore mucosal homeostasis[J]. Nat Med, 2019, 25: 690-700. DOI:10.1038/s41591-019-0393-7 |

| [10] |

Du G, Xiong L, Li X, et al. Peroxisome elevation induces stem cell differentiation and intestinal epithelial repair[J]. Dev Cell, 2020, 53: 169-184. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2020.03.002 |

| [11] |

Lan A, Blachier F, Benamouzig R, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: is there a place for nutritional supplementation?[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2015, 21: 198-207. DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000177 |

| [12] |

Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a norwegian population-based cohort[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133: 412-422. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051 |

| [13] |

De Zeeuw S, Ali UA, Donders RART, et al. Update of complications and functional outcome of the ileo-pouch anal anastomosis: overview of evidence and meta-analysis of 96 observational studies[J]. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2012, 27: 843-853. DOI:10.1007/s00384-011-1402-6 |

| [14] |

Bernstein CN, Eliakim A, Fedail S, et al. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines inflammatory bowel disease: update August 2015[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2016, 50: 803-818. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000660 |

| [15] |

Morar PS, Hodgkinson JD, Thalayasingam S, et al. Determining predictors for intra-abdominal septic complications following ileocolonic resection for Crohn's disease--considerations in pre-operative and peri-operative optimisation techniques to improve outcome[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2015, 9: 483-491. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv051 |

| [16] |

Frolkis A, Kaplan GG, Patel AB, et al. Postoperative complications and emergent readmission in children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease who undergo intestinal resection[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2014, 20: 1316-1323. DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000099 |

| [17] |

Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. Chinese consensus on diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (Beijing, 2018)[J]. Chin J Dig (中华消化杂志), 2018, 5: 173-174. |

| [18] |

Yeshi K, Ruscher R, Hunter L, et al. Revisiting inflammatory bowel disease: pathology, treatments, challenges and emerging therapeutics including drug leads from natural products[J]. J Clin Med, 2020, 9: 1273. DOI:10.3390/jcm9051273 |

| [19] |

Ho G, Cartwright JA, Thompson EJ, et al. Resolution of inflammation and gut repair in IBD: translational steps towards complete mucosal healing[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2020, 26: 1131-1143. DOI:10.1093/ibd/izaa045 |

| [20] |

Shouval DS, Rufo PA. The role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases: a review[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2017, 171: 999-1005. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2571 |

| [21] |

Fan X, Ding X, Zhang Q. Hepatic and intestinal biotransformation gene expression and drug disposition in a dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis mouse model[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2020, 10: 123-135. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2019.12.002 |

| [22] |

Pull SL, Doherty JM, Mills JC, et al. Activated macrophages are an adaptive element of the colonic epithelial progenitor niche necessary for regenerative responses to injury[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102: 99-104. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0405979102 |

| [23] |

Sarang Z, Joos G, Garabuczi E, et al. Macrophages engulfing apoptotic cells produce nonclassical retinoids to enhance their phagocytic capacity[J]. J Immunol, 2014, 192: 5730-5738. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1400284 |

| [24] |

Röszer T, Röszer T, Banfalvi G, et al. Transcriptional control of apoptotic cell clearance by macrophage nuclear receptors[J]. Apoptosis (London), 2017, 22: 284-294. DOI:10.1007/s10495-016-1310-x |

| [25] |

Seno H, Miyoshi H, Brown SL, et al. Efficient colonic mucosal wound repair requires Trem2 signaling[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106: 256-261. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0803343106 |

| [26] |

Bouchery T, Harris NL. Specific repair by discerning macrophages[J]. Science, 2017, 356: 1014. DOI:10.1126/science.aan6782 |

| [27] |

Ruder B, Becker C. At the forefront of the mucosal barrier: the role of macrophages in the intestine[J]. Cells, 2020, 9: 2162. DOI:10.3390/cells9102162 |

| [28] |

Ariel A, Serhan CN. New lives given by cell death: macrophage differentiation following their encounter with apoptotic leukocytes during the resolution of inflammation[J]. Front Immunol, 2012, 3: 4. |

| [29] |

Kroner A, Greenhalgh AD, Zarruk JG, et al. TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord[J]. Neuron, 2014, 83: 1098-1116. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.027 |

| [30] |

Sehgal A, Donaldson DS, Pridans C, et al. The role of CSF1R-dependent macrophages in control of the intestinal stem-cell niche[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9: 1272. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-03638-6 |

| [31] |

Lissner D, Schumann M, Batra A, et al. Monocyte and M1 macrophage-induced barrier defect contributes to chronic intestinal inflammation in IBD[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2015, 21: 1297-1305. |

| [32] |

Cleynen I, Boucher G, Jostins L, et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387: 156-167. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00465-1 |

| [33] |

Li M, Miao JZ, Xu S. Recent advances in research and development of new small molecule immunosuppressants for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2018, 53: 1290-1302. |

| [34] |

Van Dyken SJ, Locksley RM. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: roles in homeostasis and disease[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2013, 31: 317-343. DOI:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095906 |

| [35] |

Waqas SFH, Ampem G, Röszer T. Analysis of IL-4/STAT6 signaling in macrophages[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2019, 1966: 211. |

| [36] |

Cosín-Roger J, Ortiz-Masiá D, Calatayud S, et al. The activation of Wnt signaling by a STAT6-dependent macrophage phenotype promotes mucosal repair in murine IBD[J]. Mucosal Immunol, 2016, 9: 986-998. DOI:10.1038/mi.2015.123 |

| [37] |

Jayme TS, Leung G, Wang A, et al. Human interleukin-4-treated regulatory macrophages promote epithelial wound healing and reduce colitis in a mouse model[J]. Sci Adv, 2020, 6: a4376. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aba4376 |

| [38] |

Leung G, Petri B, Reyes JL, et al. Cryopreserved interleukin-4-treated macrophages attenuate murine colitis in an integrin beta7-dependent manner[J]. Mol Med, 2016, 21: 924-936. |

| [39] |

Bosurgi L, Cao YG, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, et al. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells[J]. Science, 2017, 356: 1072-1076. DOI:10.1126/science.aai8132 |

| [40] |

Platt AM, Bain CC, Bordon Y, et al. An independent subset of TLR expressing CCR2-dependent macrophages promotes colonic inflammation[J]. J Immunol, 2010, 184: 6843-6854. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.0903987 |

| [41] |

Waddell A, Ahrens R, Steinbrecher K, et al. Colonic eosinophilic inflammation in experimental colitis is mediated by Ly6Chigh CCR2+ inflammatory monocyte/macrophage-derived CCL11[J]. J Immunol, 2011, 186: 5993-6003. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1003844 |

| [42] |

Schleier L, Wiendl M, Heidbreder K, et al. Non-classical monocyte homing to the gut via α4β7 integrin mediates macrophage-dependent intestinal wound healing[J]. Gut, 2020, 69: 252-263. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316772 |

| [43] |

Ikeda N, Asano K, Kikuchi K, et al. Emergence of immunoregulatory Ym1+Ly6Chi monocytes during recovery phase of tissue injury[J]. Sci Immunol, 2018, 3: eaat0207. DOI:10.1126/sciimmunol.aat0207 |

| [44] |

Ishida T, Yoshida M, Arita M, et al. Resolvin E1, an endogenous lipid mediator derived from eicosapentaenoic acid, prevents dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2010, 16: 87-95. DOI:10.1002/ibd.21029 |

| [45] |

Bento AF, Claudino RF, Dutra RC, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid-derived mediators 17(R)-hydroxy docosahexaenoic acid, aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 prevent experimental colitis in mice[J]. J Immunol, 2011, 187: 1957-1969. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1101305 |

| [46] |

Marcon R, Bento AF, Dutra RC, et al. Maresin 1, a proresolving lipid mediator derived from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, exerts protective actions in murine models of colitis[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 191: 4288-4298. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1202743 |

| [47] |

Liu F, Smith AD, Solano-Aguilar G, et al. Mechanistic insights into the attenuation of intestinal inflammation and modulation of the gut microbiome by krill oil using in vitro and in vivo models[J]. Microbiome, 2020, 8: 83. DOI:10.1186/s40168-020-00843-8 |

| [48] |

Bernasconi E, Favre L, Maillard MH, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor elicits bone marrow-derived cells that promote efficient colonic mucosal healing[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2010, 16: 428-441. DOI:10.1002/ibd.21072 |

| [49] |

Schmitt H, Ulmschneider J, Billmeier U, et al. The TLR9 agonist cobitolimod induces IL10-producing wound healing macrophages and regulatory T cells in ulcerative colitis[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2020, 14: 508-524. DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz170 |

| [50] |

Zhang TH, Shen H. Thinking of syndrome differentiation and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in traditional Chinese medicine[J]. J Tradit Chin Med (中医杂志), 2019, 60: 1191-1193, 1236. |

| [51] |

Zhang BP, Cheng Y, Zhao XY. Research progress on curative effect and mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Beijing J Tradit Chin Med (北京中医药), 2020, 39: 216-219. |

| [52] |

Yan F, Wang L, Shi Y, et al. Berberine promotes recovery of colitis and inhibits inflammatory responses in colonic macrophages and epithelial cells in DSS-treated mice[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2012, 302: G504-G514. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00312.2011 |

| [53] |

Zhu W, Jin Z, Yu J, et al. Baicalin ameliorates experimental inflammatory bowel disease through polarization of macrophages to an M2 phenotype[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2016, 35: 119-126. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.030 |

| [54] |

Wang YQ, Wu C, Jiang ZL, et al. Dynamic effect of Quyu shengxin method on macrophage expression in ulcer tissue of ulcerative colitis rats[J]. Jiangsu J Tradit Chin Med (江苏中医药), 2012, 44: 65-66. |

| [55] |

Zang KH, Li YD, Zhu LJ, et al. Study on the repair effect on colon mucosa and mechanism of astragalus polysaccharides in rats with ulcerative colitis[J]. J Gansu Univ Chin Med (甘肃中医药大学学报), 2018, 35: 5-10. |

| [56] |

Liang JH, Zheng KW, Sun LQ. Explore the regulative action of astragalus polysaccharide for intestinal dysbacteriosis in ulcerative colitis rat models[J]. Stud Trace Elements Health (微量元素与健康研究), 2013, 30: 1-3. |

| [57] |

Zou ML, Huang XY, Chen YL, et al. Mechanism and experimental verification of Sijunzi Decoction in treatment of ulcerative colitis based on network pharmacology[J]. Chin J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2020, 45: 5362-5372. |

| [58] |

Zhang DP, Zhou L, Zhang ZM, et al. Effects of compound polysaccharide of Sijunzi decoction on the apoptosis of Peyer's patch lymphocytes in mice intestinal mucosa[J]. Tradit Chin Drug Res Pharmacol (中药新药与临床药理), 2009, 20: 529-532. |

| [59] |

Cao J, Cha AS. Effects of Sijunzi decoction on intestinal flora regulation of rats with ulcerative colitis[J]. Clin J Tradit Chin Med (中医药临床杂志), 2019, 31: 102-104. |

| [60] |

Yan Y, Gao WY. Research progress of Chinese medicine monomer in the treatment of ulcerative colitis[J]. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med (现代中西医结合杂志), 2017, 26: 3184-3189. |

| [61] |

Peng KY. Intervention and Mechanism of Total Phenolic Acid in Salvia Miltiorrhiza Stem-leaf and combined with Tanshinone Compatible Components on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (丹参茎叶总酚酸及与丹参酮联用组分对炎症性肠病的干预作用与机理研究) [D]. Nanjing: Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, 2020.

|

| [62] |

Villedieu-Percheron E, Ferreira V, Campos JF, et al. Quantitative determination of andrographolide and related compounds in andrographis paniculata extracts and biological evaluation of their anti-inflammatory activity[J]. Foods, 2019, 8: 683. DOI:10.3390/foods8120683 |

| [63] |

Liu QQ. Mechanism of Curcumin Regulating Autophagy to Promote Mucosal Repair of Ulcerative Colitis (姜黄素调控自噬蛋白促进溃疡性结肠炎黏膜修复的机制研究)[D]. Qingdao: Qingdao University, 2019.

|

| [64] |

Li H, Fan C, Lu H, et al. Protective role of berberine on ulcerative colitis through modulating enteric glial cells-intestinal epithelial cells-immune cells interactions[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2020, 10: 447-461. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.006 |

| [65] |

Sun W, Han X, Wu S, et al. Unexpected mechanism of colitis amelioration by artesunate, a natural product from Artemisia annua L.[J]. Inflammopharmacology, 2019, 28: 851-868. DOI:10.1007/s10787-019-00678-2 |

| [66] |

Shao MJ, Yan YX, Qi Q, et al. Application of active components from traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Chin J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2019, 44: 415-421. |

| [67] |

Zhu YP. The Research on the Repair Mechanismof Gastrointestinal Mucosal Injury of Astragali and Ginseng from the Perspective of Cell Proliferation and Adhesion (从细胞增殖和黏附连接角度探讨黄芪和人参胃肠黏膜损伤修复机制)[D]. Guangzhou: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 2019.

|

| [68] |

Qi YL. Effects of Ginseng Polysaccharides on Intestinal Microecology and Mucosal Immunity (人参多糖对肠道微生态及肠黏膜免疫作用的研究)[D]. Changchun: Jilin Agricultural University, 2019.

|

| [69] |

Chen MM, Zhu SD. Effects of APS on regeneration and repair of colonic mucosa in UC rats[J]. Clin J Chin Med (中医临床研究), 2019, 11: 1-6. |

| [70] |

Jiang XG, Sun K, Liu YY, et al. Astragaloside IV ameliorates 2, 4, 6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis implicating regulation of energy metabolism[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 41832. DOI:10.1038/srep41832 |

| [71] |

Wu XX, Huang XL, Chen RR, et al. Paeoniflorin prevents intestinal barrier disruption and inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in Caco-2 cell monolayers[J]. Inflammation, 2019, 42: 2215-2225. DOI:10.1007/s10753-019-01085-z |

| [72] |

Lin C, Kuo TC, Lin JC, et al. Delivery of polysaccharides from Ophiopogon japonicus (OJPs) using OJPs/chitosan/whey protein co-assembled nanoparticles to treat defective intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier[J]. Int J Biol Macromol, 2020, 160: 558-570. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.151 |

| [73] |

He YH, Wang YS, Du YY, et al. Network pharmacology integrates the differential genes of macrophages to explain the mechanism of patchouli oil treating IBD[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2021. DOI:10.16438/j.0513-4870.2021-0218 |

| [74] |

Zhao Y, Yang Y, Zhang J, et al. Lactoferrin-mediated macrophage targeting delivery and patchouli alcohol-based therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2020, 10: 1966-1976. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.07.019 |

| [75] |

Wang ZP, Zhang R, Liu L, et al. Effects of rhubarb polysacchrides on apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells and peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils in mice with ulcerative colitis[J]. World Chin J Dig (世界华人消化杂志), 2006, 14: 29-34. DOI:10.11569/wcjd.v14.i1.29 |

| [76] |

Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, et al. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium[J]. Genes Dev, 2003, 17: 1709-1713. DOI:10.1101/gad.267103 |

| [77] |

Saha S, Aranda E, Hayakawa Y, et al. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicle-packaged WNTs rescue intestinal stem cells and enhance survival after radiation injury[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 13096. DOI:10.1038/ncomms13096 |

| [78] |

Wang J, Kubes P. A reservoir of mature cavity macrophages that can rapidly invade visceral organs to affect tissue repair[J]. Cell, 2016, 165: 668-678. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.009 |

| [79] |

Mirza R, Koh TJ. Dysregulation of monocyte/macrophage phenotype in wounds of diabetic mice[J]. Cytokine, 2011, 56: 256-264. DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2011.06.016 |

| [80] |

Mirza RE, Fang MM, Ennis WJ, et al. Blocking interleukin-1beta induces a healing-associated wound macrophage phenotype and improves healing in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes, 2013, 62: 2579-2587. DOI:10.2337/db12-1450 |

| [81] |

Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Mitsuyama K, et al. Efficacy of indigo naturalis in a multicenter randomized controlled trial of patients with ulcerative colitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2018, 154: 935-947. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.024 |

| [82] |

Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Fukuda T, et al. Indigo naturalis is effective even in treatment-refractory patients with ulcerative colitis: a post hoc analysis from the INDIGO study[J]. J Gastroenterol, 2020, 55: 169-180. DOI:10.1007/s00535-019-01625-2 |

2021, Vol. 56

2021, Vol. 56