2. 海洋药物与生物制品实验室, 青岛海洋科学与技术试点国家实验室, 山东 青岛 266237

2. Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, China

糖尿病是一种以持续高血糖为特征的疾病。根据世界卫生组织的研究, 到2030年, 糖尿病可能成为世界人口死亡的主要原因之一[1]。2型糖尿病是由于胰岛素抵抗引起的, 常见于中老年人群体, 2型糖尿病患者常伴有血脂异常、高血压、动脉粥样硬化等疾病[2]。糖尿病伤口比正常皮肤伤口愈合缓慢, 导致了糖尿病并发症糖尿病足等, 如果治疗不当可能引起截肢等严重后果[3, 4]。糖尿病伤口难愈合的原因可能有细胞外基质形成紊乱、修复的胶原蛋白结构质量差、中性粒细胞诱捕网形成、后期炎症应答缺陷即巨噬细胞功能紊乱(TNF-α、IL-1β和VEGF释放减少), 巨噬细胞数量和活化的减少导致淋巴管的形成减少从而破坏了伤口愈合[5-9]。

糖胺聚糖(glycosaminoglycans, GAGs) 是一种广泛存在于细胞外基质和细胞表面聚糖层中的带负电荷的线性多糖, 包括硫酸软骨素、硫酸乙酰肝素和透明质酸等[10-12]。硫酸软骨素(chondroitin sulfate, CS) 是由葡萄糖醛酸(GlcA) 和N-乙酰氨基半乳糖(GalNAc) 通过β1, 3-糖苷键交替连接而成的聚合物。CS是细胞外基质(ECM) 的主要成分, 参与细胞-细胞识别、癌症转移和神经元生长调节等生命活动[13], 是炎症、伤口愈合和肿瘤发生发展过程中的重要调节因子[14]。硫酸乙酰肝素(heparan sulfate, HS) 是由N-乙酰氨基葡萄糖(GlcNAc) 和GlcA通过α1, 4-糖苷键连接组成。在体内HS与核心蛋白连接成蛋白聚糖(HSPG) 几乎存在于所有哺乳动物细胞中, 是细胞外基质的主要成分[15]。HS被证明是生长因子与受体酪氨酸激酶结合的辅助受体, HS在体内可以直接参与细胞间的信号转导与局部黏附[16]。透明质酸(hyaluronic acid, HA) 是由GlcNAc和GlcA二糖重复单位通过β1, 4-和β1, 3-糖苷键构成的酸性黏多糖, HA以游离的形式存在于动物组织细胞间质、某些细菌的荚膜和病毒蛋白中[17]。HA是皮肤和其他结缔组织的重要成分, 在伤口愈合过程中起着重要作用[18]。HA具有生物相容性、可降解性、抑菌性、抗氧化性和抗炎性等特点, 对于伤口的愈合有着积极作用[19]。

GAGs发挥着各种各样的生物功能, 包括细胞黏附、迁移、增殖、蛋白分泌和基因表达等。炎症、伤口愈合、糖尿病等一些病理过程也与GAGs有关[20]。糖尿病可能会引起GAGs的变化, GAGs结构和含量的改变影响其生物活性, 并且影响器官系统的生理功能[21]。因此, 为了追根溯源, 有必要弄清糖尿病患者皮肤中GAGs的具体变化, 以便更好地治疗糖尿病患者创面愈合。只有少数文献报道了皮肤在病理过程中GAGs的变化, 在四氧嘧啶诱导的糖尿病大鼠(alloxan diabetic rats) 皮肤中GAGs总量、HA含量和硫酸软骨素A含量比正常大鼠皮肤低, 证明了胰岛素参与GAGs的新陈代谢[22, 23]。此外, Cechowska-Pasko等[24]发现在链脲佐菌素(STZ) 诱导的糖尿病大鼠皮肤中GAGs总量、HA、Ch4S、Ch6S、DS、肝素都低于正常组, 可能原因是循环系统中胰岛素样生长因子Ⅰ (IGF-Ⅰ) 的减少导致GAGs生物合成减少, 尤其是硫酸化GAGs的合成[24-26]。但由于分析技术的限制, 没有探索糖尿病大鼠皮肤中GAGs精细结构的变化。

近年来, 随着现代糖分析技术的飞速发展, 质谱技术已经成为GAGs结构鉴定和序列分析中十分重要的工具。由于GAGs的高负电性、多分散性以及不同的硫酸化修饰等特点, GAGs的结构表征成为分析的难点。目前GAGs分析的一般方法依赖酶解获得GAGs二糖单元, 之后对二糖单元组成进行结构表征。GAGs二糖的分析方法有高效液相色谱法[27]、超高效液相色谱法[28]以及毛细管电泳[29]等技术。液相色谱-质谱联用技术(LC-MS/MS) 具有高通量、特异性强、灵敏度高、重现性强、线性范围宽等优点, 已被证明是复杂生物样品分析方法之一, LC-MS/MS技术目前广泛用于生物样品中GAGs表达谱的分析而不受样品中杂质的干扰[30, 31]。Li等[31]利用LC-MS/MS技术建立了细胞生物样本GAGs表达谱的分析方法, 能够同时定量分析多种人源细胞GAGs的组成。Weyers等[32]利用液质联用技术分析人体组织中的GAGs, 发现非硫酸化的CS的含量在胃癌患者的癌变组织中显著增加, HA显著减少。本研究采用LC-MS/MS技术对STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠和正常小鼠皮肤中GAGs表达谱进行了表征, 为进一步阐明糖尿病患者发病机制以及相关创面愈合的治疗等奠定了基础。

材料与方法药品与试剂 二糖对照品: 透明质酸二糖对照品(HA-0S: △UA-GlcNAc), 硫酸软骨素二糖对照品(CS-0S: △UA-GalNAc; CS-4S: △UA-GalNAc4S; CS-6S: △UA-GalNAc6S; CS-2S: △UA2S-GalNAc; CS-2S4S: △UA2S-GalNAc4S; CS-2S6S: △UA2S-GalNAc6S; CS-4S6S: △UA-GalNAc4S6S; CS-TriS: △UA2S-GalNAc4S6S), 硫酸乙酰肝素二糖对照品(HS-0S: △UA-GlcNAc; HS-NS: △UA-GlcNS; HS-6S: △UA-GlcNAc6S; HS-2S: △UA2S-GlcNAc; HS-2SNS: △UA2S-GlcNS; HS-NS6S: △UA-GlcNS6S; HS-2S6S: △UA2S-GlcNAc6S; HS-TriS: △UA2S-GlcNS6S), 购买自Iduron公司(曼彻斯特, 英国), 其中△UA是指不饱和的糖醛酸。戊巴比妥钠购自合肥博美生物科技有限公司。重组肝素酶Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ, 硫酸软骨素酶ABC、ACII购自北京碧澄生物科技有限公司。链脲佐菌素(STZ)、2-氨基吖啶酮(AMAC)、NaBH3CN、乙酸铵购自Sigma公司(上海, 中国)。甲醇和氯仿购自德国Merck公司。其他试剂均为分析级试剂, 购自国药集团化学试剂(上海) 有限公司。

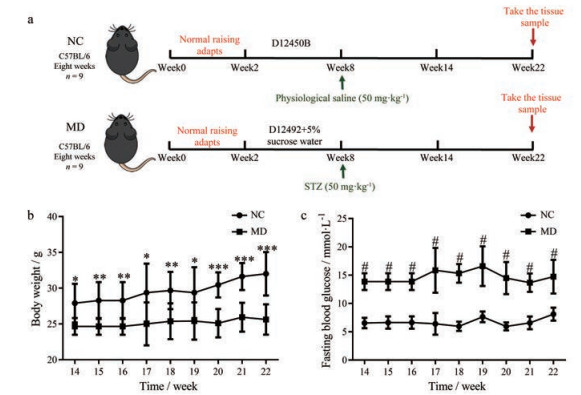

2型糖尿病小鼠模型的构建 雄性C57BL/6小鼠(8周龄, SPF级) (n = 18) 购自维通利华实验动物技术有限公司(北京, 中国), 合格证号: SCXK (京) 2016-0011。实验期间, 动物饲养环境温度控制在22 ℃期间, 并保持昼夜各12 h周期循环, 动物自由饮食、饮水。适应性喂养2周后, 随机分为对照组(n = 9) 和糖尿病组(n = 9)。对照组饲喂普通饲料(D12450B, 含有10% kcal脂肪热量, 总热量为3.85 kcal·g-1, 美国Research Diets公司), 6周内不饮用额外的水。糖尿病组饲喂高脂饲料(D12492, 含60% kcal脂肪热量, 总热量5.24 kcal·g-1, 美国Research Diets公司), 6周内饮用含5%蔗糖的饮用水。饲喂6周后, 糖尿病组腹腔注射STZ (50 mg·kg-1体重), 对照组腹腔注射相同剂量的无菌生理盐水。通过小鼠尾静脉采集血液样本, 使用血糖仪(强生中国医疗器材有限公司) 测量和监测血糖水平。STZ注射后6周后, 选用血糖高于11.0 mmol·L-1的小鼠作为糖尿病小鼠模型开展实验[33]。STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠成功率约为80%。所有动物实验程序均经中国海洋大学伦理委员会批准(批准号: KYBF临审字第2016-001)。

小鼠皮肤样品处理 正常小鼠(n = 7) 和2型糖尿病小鼠(n = 7) 经腹腔注射1%戊巴比妥钠(60 mg·kg-1) 进行麻醉, 并用电动剃毛刀和刀片去除小鼠背部毛发, 剪下全皮层皮肤组织, 分别命名NC组和MD组。

皮肤组织中GAGs的分离纯化 取小鼠皮肤组织80 mg, 充分剪碎后悬浮于氯仿-甲醇(2∶1, 体积比) 中室温过夜脱脂, 沉淀加水溶解, 加入灰色链霉菌蛋白酶于55 ℃水浴酶解20 h。离心(10 000 r·min-1, 30 min) 后, 上清液过0.22 μm微孔滤膜后过超滤膜(截留分子量: 3 kDa), 并收取截留部分, 冷冻干燥。冻干样品溶解在0.4 mL蛋白质变性液(8 mol·L-1尿素, 2% Chaps) 中, 上样于Vivapure MiniQH离子交换色谱柱, 并用0.2 mol·L-1 NaCl洗脱以去除杂质, 然后用2.0 mol·L-1 NaCl洗脱得到GAGs组分, 脱盐后冷冻干燥。

皮肤组织中GAGs二糖的获得 GAGs样品加入混合的GAGs酶溶液(硫酸软骨素酶ABC和ACⅡ, 肝素降解酶Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ, 各40 mU), 轻轻混匀后于振荡培养箱中35 ℃、5 h。将GAGs降解酶灭活后, 生成的GAGs二糖溶液经超滤离心管收集(截留分子量: 10 kDa) 并冷冻干燥。

GAGs二糖的AMAC标记 取冻干后的样品与二糖对照品, 加入0.1 mol·L-1 AMAC溶液(溶于DMSO∶乙酸= 17∶3) 10 μL, 漩涡振荡混匀后于室温静置30 min, 然后加入等体积新配制的1 mol·L-1氰基硼氢化钠水溶液, 混匀后于45 ℃反应4.5 h。将对照品经50%的DMSO稀释成不同的浓度与样品的GAGs二糖用于LC-MS/MS分析。

GAGs二糖的LC-MS/MS分析 采用色谱柱Poroshell 120 C18 (3.0 mm × 150 mm, 2.7 μm) 于Agilent 1200高效液相色谱系统中二元泵高压混合进行梯度洗脱, 并采用配有电喷雾离子源(ESI) 的TSQ Quantum UltraTM质谱仪进行质谱分析, 色谱洗脱组分经ESI源直接进入质谱系统。流动相A: 15%甲醇水溶液(含pH 6.5的50 mmol·L-1醋酸铵), 流动相B: 65%甲醇水溶液(含pH 6.5的50 mmol·L-1醋酸铵), 采用流速为100 μL·min-1, 洗脱程序为0% B, 0~5 min; 0~12% B, 5~10 min; 12%~25% B, 10~35 min; 25%~100% B, 35~50 min。负离子模式下检测, 喷雾电压为3.2 kV, 气化温度为350 ℃, 扫描方式: 多重反应检测(MRM)。进样量: 4 μL, 柱温: 45 ℃。基于二糖对照品的进样量以及MRM峰面积进行标准曲线的绘制。根据二糖对照品(8、40、200、1 000、5 000、10 000和16 700 pg·μL-1) 的标准曲线对AMAC标记的样品GAGs二糖进行定量分析[31]。

统计学分析 实验结果用平均值±标准差(mean ± SD) 表示, 使用GraphPad Prism 8软件进行学生t检验。

结果与讨论 1 STZ诱导2型糖尿病小鼠模型的构建正常小鼠和STZ诱导2型糖尿病小鼠模型构建的流程图如图 1a所示。在注射STZ6周后, STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠表现出常见的糖尿病症状, 体重低于对照组(图 1b)。第14~22周, STZ诱导的小鼠血糖水平明显高于对照组(图 1c), 选择第22周的小鼠进行研究[26]。

|

Figure 1 Establishment of a mouse model of type 2 diabetes (a); monitoring of body weight (b) and fasting blood glucose (c) of mice. NC: Normal mice group; MD: Type 2 diabetic mice group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, #P < 0.001 vs MD |

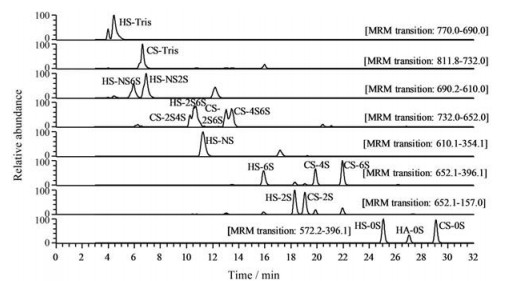

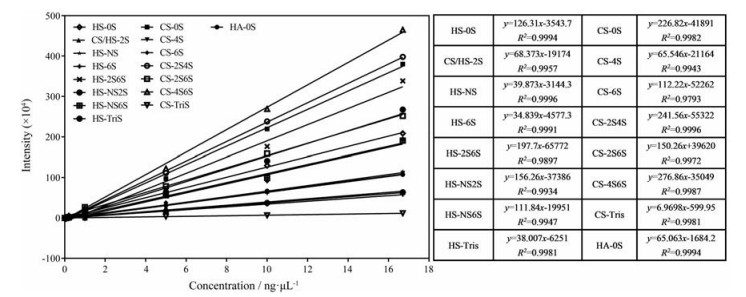

利用LC-MS/MS技术建立了生物样本GAGs表达谱的分析方法, 基于质谱的MRM技术同时对17种GAGs二糖进行定量分析, 该方法具有很高的灵敏度, 可以同时得到17种GAGs二糖单元的标准曲线, 提高了分析效率。0.008~16.7 ng·μL-1的二糖对照品通过LC-MS/MS进行检测。17种AMAC标记的GAGs二糖对照品的MRM色谱图如图 2所示。通过LC-MS/MS可以将17种GAGs二糖混合物进行分离。样品中GAGs二糖的含量可以通过二糖对照品的线性回归方程(图 3) 进行计算, 结果显示, 标准曲线的线性关系良好, 可以用于样品中GAGs二糖含量的计算[34]。

|

Figure 2 Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) chromatograms of 17 2-aminoacridone (AMAC)-labeled glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) disaccharide standards. HA-0S: △UA-GlcNAc; CS-0S: △UA-GalNAc; CS-4S: △UA-GalNAc4S; CS-6S: △UA-GalNAc6S; CS-2S: △UA2S-GalNAc; CS-2S4S: △UA2S-GalNAc4S; CS-2S6S: △UA2S-GalNAc6S; CS-4S6S: △UA-GalNAc4S6S; CS-TriS: △UA2S-GalNAc4S6S; HS-0S: △UA-GlcNAc; HS-NS: △UA-GlcNS; HS-6S: △UA-GlcNAc6S; HS-2S: △UA2S-GlcNAc; HS-2SNS: △UA2S-GlcNS; HS-NS6S: △UA-GlcNS6S; HS-2S6S: △UA2S-GlcNAc6S; HS-TriS: △UA2S-GlcNS6S |

|

Figure 3 Sensitivity of analysis by using the LC-MS/MS method of AMAC-derivatized standard disaccharides. The curves and linear equations of intensity as a function of concentration for each disaccharide from 0.008 to 16.7 ng·μL-1 with their related coefficients of correlation are shown |

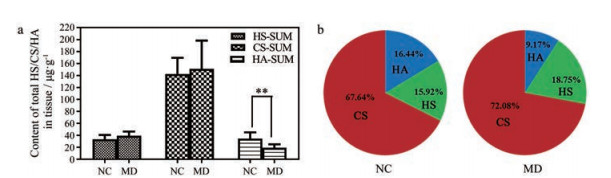

结果发现, STZ诱导2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中HA含量明显低于对照组(P < 0.01)。HA作为细胞外基质的重要成分之一, 不仅可以参与伤口愈合过程, 还可以降解为低分子HA和HA低聚糖, 协同参与加速伤口愈合[35]。STZ诱导2型糖尿病小鼠和对照组小鼠皮肤中HS和CS的含量接近(图 4a)。NC组中HA、HS和CS的百分占比为16.44%、15.92%和67.64%, MD组中HA、HS和CS的百分占比为9.17%、18.75%和72.08% (图 4b), 这些结果与之前的文献报道有一定的出入[24], 可能是由于不同的动物模型、年龄和实验分析方法导致。文献研究使用的是Wistar大鼠, 本研究则使用的是C57BL/6小鼠。此外, 以往研究的分析方法为咔唑比色法, 特异性和准确度均不高, 糖醛酸可能被其他非GAGs类物质污染[36]。

|

Figure 4 Comparison of total content of heparan sulfate (HS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), and hyaluronic acid (HA) in normal and streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice skin (a), relative amounts of HS, CS, and HA in GAGs from normal (left) and STZ-induced diabetic mice skin (right) (b). HS-SUM: HS total content; CS-SUM: CS total content; HA-SUM: HA total content. **P < 0.01 |

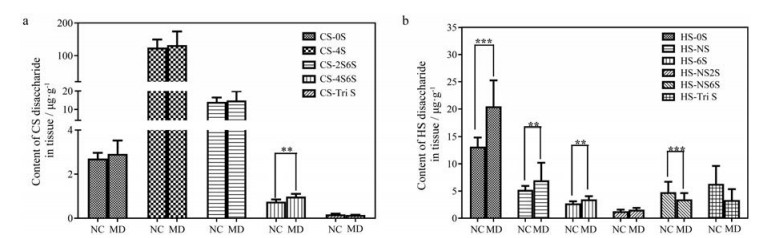

虽然HS、CS在2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤和正常小鼠皮肤中的含量没有显著性差异, 但是在HS和CS的精细结构中, 存在较大差异(图 5)。STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中CS-4S6S、HS-0S、HS-NS和HS-6S均显著高于正常组, HS-NS6S显著低于正常组。GAGs的二糖组成以及分子质量大小对其性质和生物功能都很重要, HA具有抗血管生成活性[37], 而低分子质量的HA具有促血管生成活性[38]。低分子质量硫酸皮肤素、CS和HS的混合物可以用作抗凝血剂, 并且不具有肝素诱导的血小板减少的不良反应[39]。因此, GAGs的精细结构的改变可能会导致机体生理功能的改变。

|

Figure 5 Comparison of disaccharide composition of CS (a) and HS (b) between the normal mice skin and the STZ-induced diabetic mice skin. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 |

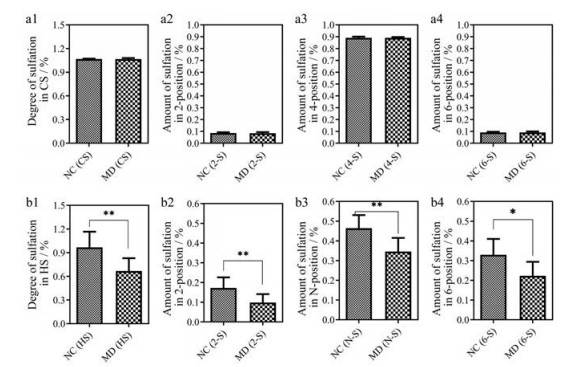

GAGs的结构中存在不同的硫酸化修饰。对其硫酸化修饰进一步分析发现, 小鼠皮肤GAGs的CS的硫酸化程度不存在显著性差异(图 6a1~a4)。而STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠组(MD) 中HS的硫酸化程度显著低于NC组(图 6b1), 并且HS的2位、N位、6位硫酸化都显著低于NC组(图 6b2~6b4)。生物体内的HS是很多生长因子、成形素和黏附蛋白的受体, 在生理过程中具有不同的结构特征[40]。有研究表明, 对于血管内皮生长因子VEGF165的活性, 肝素/硫酸乙酰肝素中己糖醛酸2位硫酸化、GlcN上N-硫酸化和6-硫酸化是必须的[41], 提高HS中N-和6-O-硫酸化能够明显满足HS在重要的VEGF和FGF信号通路中的要求[42]。根据研究结果表明, STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠中HS的差异表达可能是导致糖尿病患者伤口难以愈合的原因之一。因此, 将来如果能够开发出促进HS硫酸化修饰生物合成的药物将有利于糖尿病患者伤口愈合。本研究结果可为糖尿病创面愈合的表观遗传治疗提供参考[43]。

|

Figure 6 Comparison of degree of sulfation in CS (a1), amount of sulfation in 2-position of CS (a2), amount of sulfation in 4-position of CS (a3), amount of sulfation in 6-position of CS (a4) between the normal mice skin and the STZ-induced diabetic mice skin; Comparison of degree of sulfation in HS (b1), amount of sulfation in 2-position of HS (b2), amount of sulfation in N-position of HS (b3), amount of sulfation in 6-position of HS (b4) between the normal mice skin and the STZ-induced diabetic mice skin. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 |

2型糖尿病是一种普遍存在的疾病, 糖尿病会导致视力下降、截肢和肾脏疾病等并发症。本研究通过LC-MS/MS技术对STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中GAGs精细结构进行了表征。研究发现正常小鼠皮肤与STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中GAGs精细结构含量的区别, 以组织湿重计, 比较发现CS和HS在总量上没有区别, 但是其精细结构存在较多显著性差异, STZ诱导的2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中HA的总量明显低于正常组, 表明2型糖尿病可能影响GAGs的生物合成和降解。导致糖尿病伤口愈合缓慢的原因可能是GAGs精细结构含量的差异, 于是进一步研究了GAGs二糖组成和含量的差异, 发现在2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中CS-4S6S、HS-0S、HS-NS和HS-6S均显著高于正常组, HS-NS6S显著低于正常组。2型糖尿病小鼠皮肤中HS的2位、N位、6位硫酸化都显著低于正常小鼠。本研究结果能够为糖尿病病理机制的研究提供依据, 并能为开发治疗糖尿病伤口愈合的伤口敷料提供一定的指导。

作者贡献: 于广利和李国云负责实验方案设计及论文修改; 丁琅负责查阅文献、实验操作、数据分析和文章撰写; 张昕负责查阅文献、数据分析和文章撰写; 李芹英和王晨参与数据分析; 尚庆森负责小鼠模型的构建; 于广利、李国云和蔡超对文章进行修改、审定。

利益冲突: 本文所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030[J]. PLoS Med, 2006, 3: e442. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 |

| [2] |

Farag YMK, Gaballa MR. Diabesity: an overview of a rising epidemic[J]. Nephrol Dial Transpl, 2011, 26: 28-35. DOI:10.1093/ndt/gfq576 |

| [3] |

Volmer-Thole M, Lobmann R. Neuropathy and diabetic foot syndrome[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17: 917. DOI:10.3390/ijms17060917 |

| [4] |

Wang NQ, Yang XY, Du GH. Advances in research on mechanisms of diabetic wound healing[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2020, 55: 2811-2817. |

| [5] |

Wong SL, Demers M, Martinod K, et al. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing[J]. Nat Med, 2015, 21: 815. DOI:10.1038/nm.3887 |

| [6] |

Shakya S, Wang Y, Mack JA, et al. Hyperglycemia-induced changes in hyaluronan contribute to impaired skin wound healing in diabetes: review and perspective[J]. Int J Cell Biol, 2015, 2015: 701738. |

| [7] |

Zykova SN, Jenssen TG, Berdal M, et al. Altered cytokine and nitric oxide secretion in vitro by macrophages from diabetic type Ⅱ-like db/db mice[J]. Diabetes, 2000, 49: 1451-1458. DOI:10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1451 |

| [8] |

Maruyama K, Asai J, Li M, et al. Decreased macrophage number and activation lead to reduced lymphatic vessel formation and contribute to impaired diabetic wound healing[J]. Am J Pathol, 2007, 170: 1178-1191. DOI:10.2353/ajpath.2007.060018 |

| [9] |

Cavelti-Weder C, Furrer R, Keller C, et al. Inhibition of IL-1β improves fatigue in type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2011, 34: e158. DOI:10.2337/dc11-1196 |

| [10] |

Cole GJ, Burg M. Characterization of a heparan sulfate proteoglycan that copurifies with the neural cell adhesion molecule[J]. Exp Cell Res, 1989, 182: 44-60. DOI:10.1016/0014-4827(89)90278-4 |

| [11] |

Poole AR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: structures and functions[J]. Biochem J, 1986, 236: 1-14. DOI:10.1042/bj2360001 |

| [12] |

Ruoslahti E. Proteoglycans in cell regulation[J]. J Biol Chem, 1989, 264: 13369-13372. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)80001-1 |

| [13] |

Zhang X, Liu H, Yao W, et al. Semisynthesis of chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides based on the enzymatic degradation of chondroitin[J]. J Org Chem, 2019, 84: 7418-7425. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.9b00112 |

| [14] |

Afratis N, Gialeli C, Nikitovic D, et al. Glycosaminoglycans: key players in cancer cell biology and treatment[J]. FEBS J, 2012, 279: 1177-1197. DOI:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08529.x |

| [15] |

Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology[J]. Nature, 2007, 446: 1030-1037. DOI:10.1038/nature05817 |

| [16] |

Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance[J]. J Cell Sci, 2007, 120: 1829-1832. DOI:10.1242/jcs.03432 |

| [17] |

Weigel PH, Deangelis PL. Hyaluronan synthases: a decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases[J]. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282: 36777-36781. DOI:10.1074/jbc.R700036200 |

| [18] |

Croce MA, Dyne K, Boraldi F, et al. Hyaluronan affects protein and collagen synthesis by in vitro human skin fibroblasts[J]. Tissue Cell, 2001, 33: 326-331. DOI:10.1054/tice.2001.0180 |

| [19] |

Eliezer M, Sculean A, Miron RJ, et al. Hyaluronic acid slows down collagen membrane degradation in uncontrolled diabetic rats[J]. J Periodontal Res, 2019, 54: 644-652. DOI:10.1111/jre.12665 |

| [20] |

Alexopoulou AN, Multhaupt HAB, Couchman JR. Syndecans in wound healing, inflammation and vascular biology[J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2007, 39: 505-528. DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.014 |

| [21] |

Gowd V, Gurukar A, Chilkunda ND. Glycosaminoglycan remodeling during diabetes and the role of dietary factors in their modulation[J]. World J Diabetes, 2016, 7: 67-73. DOI:10.4239/wjd.v7.i4.67 |

| [22] |

Kofoed JA, Bozzini CE, Alippi RM. Skin acidic glycosaminoglycans in alloxan diabetic rats[J]. Diabetes, 1970, 19: 732-733. DOI:10.2337/diab.19.10.732 |

| [23] |

Schiller S, Dorfman A. The distribution of acid mucopolysaccharides in skin of diabetic rats[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1963, 78: 371-373. DOI:10.1016/0006-3002(63)91649-4 |

| [24] |

Cechowska-Pasko M, Palka J, Bankowski E. Decrease in the glycosaminoglycan content in the skin of diabetic rats. The role of IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins and proteolytic activity[J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 1996, 154: 1-8. DOI:10.1007/BF00248454 |

| [25] |

Cechowska-Pasko M, Palka J, Bankowski E. Alterations in glycosaminoglycans in wounded skin of diabetic rats. A possible role of IGF-I, IGF-binding proteins and proteolytic activity[J]. Acta Biochim Pol, 1996, 43: 557-565. DOI:10.18388/abp.1996_4491 |

| [26] |

Cechowska-Pasko M, Palka J, Bankowski E. Decreased biosynthesis of glycosaminoglycans in the skin of rats with chronic diabetes mellitus[J]. Exp Toxicol Pathol, 1999, 51: 239-243. DOI:10.1016/S0940-2993(99)80105-5 |

| [27] |

Rice KG, Kim YS, Grant AC, et al. High-performance liquid chromatographic separation of heparin-derived oligosaccharides[J]. Anal Biochem, 1985, 150: 325-331. DOI:10.1016/0003-2697(85)90518-4 |

| [28] |

Jones CJ, Beni S, Larive CK. Understanding the effect of the counterion on the reverse-phase ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography (RPIP-HPLC) resolution of heparin-related saccharide anomers[J]. Anal Chem, 2011, 83: 6762-6769. DOI:10.1021/ac2013724 |

| [29] |

Volpi N, Maccari F, Linhardt RJ. Quantitative capillary electrophoresis determination of oversulfated chondroitin sulfate as a contaminant in heparin preparations[J]. Anal Biochem, 2009, 388: 140-145. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2009.02.012 |

| [30] |

Yang B, Chang Y, Weyers AM, et al. Disaccharide analysis of glycosaminoglycan mixtures by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry[J]. J Chromatogr A, 2012, 1225: 91-98. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.12.063 |

| [31] |

Li G, Li L, Tian F, et al. Glycosaminoglycanomics of cultured cells using a rapid and sensitive LC-MS/MS approach[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2015, 10: 1303-1310. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00011 |

| [32] |

Weyers A, Yang B, Park JH, et al. Microanalysis of stomach cancer glycosaminoglycans[J]. Glycoconjugate J, 2013, 30: 701-707. DOI:10.1007/s10719-013-9476-8 |

| [33] |

Leiter EH. Multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia and insulitis in C57BL mice: influence of inbred background, sex, and thymus[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1982, 79: 630-634. DOI:10.1073/pnas.79.2.630 |

| [34] |

Volpi N. High-performance liquid chromatography and on-line mass spectrometry detection for the analysis of chondroitin sulfates/hyaluronan disaccharides derivatized with 2-aminoacridone[J]. Anal Biochem, 2010, 397: 12-23. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2009.09.030 |

| [35] |

Aya KL, Stern R. Hyaluronan in wound healing: rediscovering a major player[J]. Wound Repair Regen, 2014, 22: 579-593. DOI:10.1111/wrr.12214 |

| [36] |

Frazier SB, Roodhouse KA, Hourcade DE, et al. The quantification of glycosaminoglycans: a comparison of HPLC, carbazole, and alcian blue methods[J]. Open Glycosci, 2008, 1: 31-39. DOI:10.2174/1875398100801010031 |

| [37] |

Necas J, Bartosikova L, Brauner P, et al. Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): a review[J]. Vet Med-Czech, 2008, 53: 397-411. DOI:10.17221/1930-VETMED |

| [38] |

Cui X, Xu H, Zhou S, et al. Evaluation of angiogenic activities of hyaluronan oligosaccharides of defined minimum size[J]. Life Sci, 2009, 85: 573-577. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2009.08.010 |

| [39] |

Lubenow N, Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, et al. Results of a systematic evaluation of treatment outcomes for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients receiving danaparoid, ancrod, and/or coumarin explain the rapid shift in clinical practice during the 1990s[J]. Thromb Res, 2006, 117: 507-515. DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2005.04.011 |

| [40] |

Merry CLR, Bullock SL, Swan DC, et al. The molecular phenotype of heparan sulfate in the Hs2st-/- mutant mouse[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276: 35429-35434. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M100379200 |

| [41] |

Ashikari-Hada S, Habuchi H, Kariya Y, et al. Heparin regulates vascular endothelial growth factor(165)-dependent mitogenic activity, tube formation, and its receptor phosphorylation of human endothelial cells. Comparison of the effects of heparin and modified heparins[J]. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280: 31508-34515. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M414581200 |

| [42] |

Kreuger J, Spillmann D, Li JP, et al. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins: the concept of specificity[J]. J Cell Biol, 2006, 174: 323-327. DOI:10.1083/jcb.200604035 |

| [43] |

Piperigkou Z, Goette M, Theocharis AD, et al. Insights into the key roles of epigenetics in matrix macromolecules-associated wound healing[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2018, 129: 16-36. |

2021, Vol. 56

2021, Vol. 56