2. 山东中医药大学药学院, 山东 济南 250355

2. College of Pharmacy, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan 250355, China

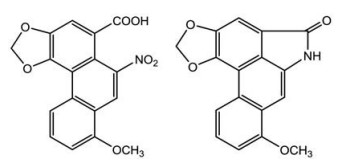

马兜铃酸类物质(aristolochic acids, AAs) 是首个从植物中发现的硝基菲类有机酸, 为3, 4-次甲二氧基-10-硝基-1-菲酸的衍生物, 包括马兜铃酸(AA) 和马兜铃内酰胺(AL) 两种结构类型(图 1)。马兜铃酸的毒性与结构密切相关, 结构中硝基、甲氧基和羟基的取代不同是决定其毒性强弱的关键因素; 通常马兜铃酸Ⅰ (AAⅠ) 的毒性最强, 马兜铃酸Ⅱ (AAⅡ) 次之, 而马兜铃酸Ⅲa、马兜铃酸ⅠV等同类物质毒性相对较弱; 对AAⅠ结构的化学修饰如加成、消除和置换等能够减小其毒性[1, 2]。AAs通常为黄色至棕色固体(粉末或结晶), 味微苦, 可溶于甲醇、氯仿、二甲基亚砜和丙酮等溶剂, 熔点在270~290 ℃。AAs虽具有抗菌、抗肿瘤、抗血小板聚集和抑制血小板活化因子(PAF) 等生物活性[3-5], 但因具有肾毒性、肝毒性、致癌和致突变等作用, 故已被国际癌症研究机构列为Ⅰ级致癌物[6]。AAⅠ在17种中成药中均表现高溶解性和渗透性, 口服后能快速溶出, 进入体内后会被迅速吸收和分布, 而渗透性为影响其吸收的限速因素; AAI的体内分布具有器官特异性, 主要集中在肝和肾组织中, 且蓄积程度高[7, 8]。1993年, Vanherweghem等[9]发现比利时妇女因服用含马兜铃酸类成分的减肥药而出现肾间质纤维化甚至肾功能衰竭, 引发了全世界对马兜铃酸类成分毒性机制和安全合理用药的研究。2017年, 新加坡和台湾研究人员对亚洲各地共1 400例肝癌样本进行了基因检测, 认为马兜铃酸与亚洲人的肝癌发生相关, 再次对含马兜铃酸类物质的中药安全性提出了质疑[10]。研究发现, AAⅠ和AAⅡ的硝基还原有利于脱氧核苷酸和脱氧鸟苷在DNA中形成马兜铃酸加合物; 而肝脏和肾脏中的细胞色素P450黄嘌呤氧化酶、NAD(P)H脱氢酶和磺基转移酶等48种不同的酶可硝化还原, 并形成DNA加合物类型的具有遗传毒性的代谢物[11]。本文对含AAs的药用资源及其制剂和生物标志物的检测, 以及对AAs的减毒方法进行了详细的综述, 为其用药安全性提供参考。

|

Figure 1 Structures of aristolochic acid Ⅰ (left) and aristololactam Ⅰ (right) |

AAs主要存在于马兜铃科(Aristolochiaceae) 植物中, 也是该科主要代表性成分。马兜铃科植物分为细辛亚科(Subfam. Asaroideae) 和马兜铃亚科(Subfam. Aristolochioideae), 共8个属(马兜铃属Aristolochia L.、细辛属Asarum L.、马蹄香属Saruma Oliv.、线果兜铃属Thottea Rottb.、星果兜铃属Euglypha Chodat & Hassl.、杜衡属Heterotropa C.Morren & Decne.、番兜铃属Hexastylis Raf.和闭果兜铃属Pararistolochia Hutch. & Dalziel), 有600多种植物, 广布于热带和亚热带地区。我国有马兜铃属、细辛属、马蹄香属和线果兜铃属4个属, 71种、6变种和4变型药用植物, 除华北和西北干旱地区外, 全国各地均有分布[12, 13]。马兜铃属在马兜铃科植物中种类最多且分布最广, 约有350种, 而AAs在马兜铃属存在最为广泛且含量最高[14]。

美国食品药品监督管理局于2000年公布了含有AAs的植物名单, 包括马兜铃科、木通科和毛茛科等十几种植物, 其中有马兜铃、关木通、广防己、青木香、天仙藤、朱砂莲、寻骨风、细辛和杜衡共9种马兜铃科植物[15, 16]。2003年, 我国取消了关木通的药物标准, 次年又取消了广防己和青木香的药物标准并禁止使用。2007年, 国家食品药品监督管理局公布了24种含AAs的马兜铃科中药及47种含AAs中药的已上市中成药名单, 并要求严格按照处方药管理。2015年版《中国药典》仅对细辛的根及根茎和天仙藤的AAⅠ含量制定了限量标准, 但2020年版《中国药典》只收录了细辛, 取消了天仙藤的药物标准。然而, 部分含有AAs的中药仍收录于地方中药材标准中, 却未规定马兜铃酸使用限量, 在市场上流通存在安全隐患, 对此应予以高度重视。作者对含AAs中药及其AAⅠ的含量进行了统计(表 1)。通常AAⅠ的含量高于AAⅡ, 如朱砂莲、背蛇生、木通马兜铃和异叶马兜铃等药材中AAⅠ的含量较高, 而较为特殊的是, 木通马兜铃叶中AAⅡ的含量高于AAⅠ[17, 18]。

| Table 1 Herbs containing aristolochic acids (AAs). " - " means there is no relevant literature. AAⅠ: Aristolochic acid Ⅰ |

AAs在人体内具有可蓄积毒性, 长期或大量摄入会导致肾间质纤维化、急慢性肾功能衰竭、肝癌和尿路上皮癌等疾病, 因而早期发现是预防和治疗马兜铃酸药源性疾病的关键[19]。随着生物医学领域的不断发展, 发现AAs所致疾病的早期生物标志物并采用快速有效的手段对其进行检测, 已成为研究热点。

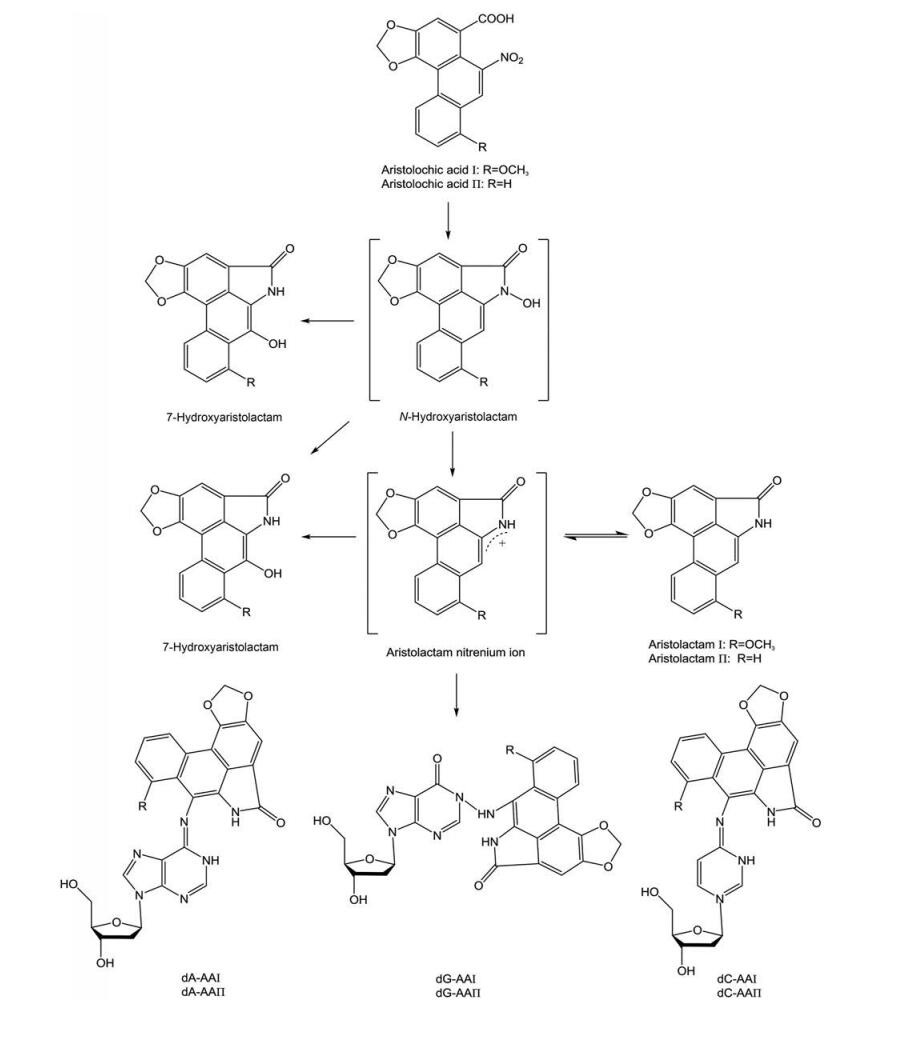

2.1 AA-DNA加合物的检测AAI在体内有代谢外排和活化产毒两种生物转化路径。在服用AAⅠ的大鼠模型中, AAⅠ在肾脏组织中可代谢为AAⅠa、AAⅠa-硫酸盐、ALⅠa、ALⅠ和ALⅠa-O-葡萄糖醛酸等物质。其代谢途径是, AAⅠa先经CYP1A催化氧化脱甲基, 再由尿苷二磷酸葡萄糖醛酸基转移酶或/和磷酸转移酶催化, 最后以游离或复合物的形式被排出体外。在活化产毒过程中, AAⅠ在硝基还原酶的催化作用下生成环状硝酰基氮正离子, 所生成的氮正离子一部分转化为AL, 另一部分则在还原过程中与DNA核苷酸的环外氨基结合生成AA-DNA加合物(图 2), 进而诱导基因发生A: T到T: A的异位突变, 使肿瘤抑制基因P53突变失去正常功能, 最终导致肿瘤的发生[20, 21]。在马兜铃酸肾病(aristolochic acid nephropathy, AAN) 患者和服用AAs的啮齿动物体内, 常见的AA-DNA加合物有AAⅠ-dA、AAⅠ-dG、AAⅡ-dA、AAⅡ-dG、AAⅠ-dC和AAⅡ-dC等, 其中AAⅠ-dA因难以被代谢而在肾脏持久蓄积, 在接触AAs几十年后的AAN患者体中仍可检测到[22-26]。因此, AA-DNA加合物在肿瘤发生过程中起着关键的作用, 是检测AAs的生物标志物, 对于深入研究AAs的致癌和致突变性具有重要意义[27-31]。目前可分析检测AA-DNA加合物的技术主要有液-质联用法、高效液相色谱法、32P后标记法、免疫技术和荧光技术等。

|

Figure 2 Synthesis pathway of AA-DNA adducts. AA: Aristolochic acid |

高效液相色谱的紫外检测(HPLC-UV) 和荧光检测(HPLC-FLD) 等技术均可用于AA-DNA加合物的分析, 通过HPLC方法可对AA-DNA加合物进行分析定量。Chan等[32]建立的HPLC-FLD法灵敏度高, 可用于单次口服AAs后大鼠肾组织中AA-DNA加合物的检测, 检测结果为给予5和30 mg·kg-1 AAs大鼠的肾脏中, AAⅡ-dA加合物的含量分别为每109个正常dA中含6.2 ± 1.1和41.3 ± 8.0个AAⅡ-dA加合物。AL是AAs的主要解毒代谢物, 可被细胞色素P450和过氧化物酶激活而形成AA-DNA加合物, 在动物和人的尿液和粪便中均可检测到。Pfau等[33]采用HPLC-UV对AA-DNA加合物进行了分析, 发现AAⅡ-dA、AAⅠ-dA和AAⅠ-dG的紫外吸收光谱与AL的紫外吸收光谱相似。

LC-MS是目前最佳的加合物检测手段, 可用于AAs生物标志物的筛选、定性、定量和结构解析等工作[34, 35]。Guo等[36]发现, 加合物dA-ALⅠ可以高产率地从小鼠的福尔马林固定石蜡包埋(FFPE) 保存组织中提取, 利用UPLC-ESI-IT-MS3对其定量检测发现, FFPE组织中dA-ALⅠ的含量高于新鲜冰冻组织, 平均含量差异可达1.5倍。Yun等[37]采用相同的UPLC-ESI-MS3技术, 分别从用致癌物处理的小鼠冷冻组织和人FFPE肾脏组织中定量比较dA-ALⅠ等多种加合物的含量, 这种快速定量方法可缩短处理DNA所需的时间。采用液质定量技术, Guo等[38]以利血平为内标物测定给予AAⅠ大鼠尿脱落细胞中AAⅠ-dA加合物的含量, 并通过多反应监测模式对加合物进行定量分析。AAⅠ给药(10 mg·kg-1·d-1) 1个月后, 从大鼠尿脱落细胞每109个正常dA中可检测到2.1 ± 0.3个AAⅠ-dA加合物。Chan等[39, 40]利用化学方法合成了AA-DNA加合物并制备纯化, 采用UPLC-ESI-MS检测到6种AA-DNA加合物, 首次鉴定了AA-dC加合物。对服用AAI和AAII的大鼠肾脏和肝脏的3种DNA加合物进行定量分析, 检测到给予5 mg·kg-1马兜铃酸大鼠肾组织中AAⅠ-dA和AAⅡ-dA的含量分别为0.9个/109个正常核苷酸和1.6个/109个正常核苷酸, 而AAⅠ-dC因含量过低而无法定量, 另外肝组织也未检测到这3种DNA加合物; 在给予30 mg·kg-1马兜铃酸大鼠肾组织中AAⅠ-dA、AAⅡ-dA和AAⅠ-dC的含量分别为4.0个/109个正常核苷酸、6.2个/109个正常核苷酸和1.2个/109个正常核苷酸; 肝组织中AAⅠ-dA和AAⅡ-dA的含量分别为2.0个/109个正常核苷酸和1.6个/109个正常核苷酸; 另外, 服用马兜铃酸5 mg·kg-1的大鼠肝脏中未发现AA-DNA加合物, 而服用马兜铃酸30 mg·kg-1的大鼠肝脏中AA-DNA加合物的总含量为3.6个/109个正常核苷酸。Yun等[41]利用分化良好的膀胱移行上皮细胞系RT4细胞作为体外的尿液细胞模型, RT4细胞经AAⅠ预处理后, 细胞存活率超过80%, 经LC-MS测定后发现, 其主要加合物在24 h内稳定。

2.1.2 荧光技术AA硝基还原产物AL具有较强的荧光特性, 因此含有AL结构片段的AA-DNA加合物也具有高特异性荧光[33]。Romanov等[42]开发出一种非同位素的以荧光为基础的快速分析方法, 可同时检测大量样本中的AA-DNA加合物, 与32P后标记法和液-质联用技术相比价格低廉、简便快速, 但灵敏度欠佳。AAs能够淬灭人血清白蛋白(HAS) 的天然荧光, 利用这一特性, Li等[43]研究了AAs对牛血清白蛋白和溶菌酶的蛋白结合特性, 光谱荧光分析和质谱分析表明, AAⅡ的蛋白质结合特性明显强于AAⅠ。这说明AAⅡ更具有高致突变性。

2.1.3 32P-后标记法32P-后标记法主要依赖各种色谱法(如薄层色谱) 进行分离, 起初被广泛用于检测AA-DNA加合物和各种形式的DNA损伤, 但由于其特异性较差和稳定性不足等问题, 近年来逐渐被色谱-质谱联用技术所取代。Schmeiser等[44]采用32P-后标记法从AAN患者的肾组织中发现了1个主要加合物AAI-dA, 证明了AAs与人类泌尿系统恶性肿瘤具有相关性。32P-后标记法也常与多种技术相结合来检测AA-DNA加合物。Grollman等[45]采用32P-后标记/聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳技术, 对AAN患者的肾皮质进行检测, 检测到了dA-AL和dG-AL DNA的加合物。

2.2 其他生物标志物的检测除AA-DNA加合物外, 微量白蛋白尿[46]、血小板反应蛋白1和G偶联蛋白受体87[47]、AA-RNA加合物[48]、N6-甲酰赖氨酸[49]等都可以作为马兜铃酸暴露的生物标志物, 而且核磁共振技术(NMR) 和气质联用技术(GC-MS) 等也是生物标志物的常用检测技术。

Mantle等[50]将肾病患者分为罗马尼亚AAN患者组、保加利亚AAN患者组和对照组, 用核磁共振波谱法比较患有AAN并接受血液透析治疗者与没有明显肾脏疾病者的尿液代谢组学差异。数据显示, 与罗马尼亚AAN患者相比, 在保加利亚AAN患者尿液样本中可观察到更高水平的柠檬酸盐、三甲胺-N-氧化物和丙酮酸盐等代谢物。α-2-微球蛋白被认为是肾小管的标志物, 而血清白蛋白则是肾小球蛋白尿的标志物, Huang等[51]给小鼠灌胃AAⅠ和AAⅡ建立了AAN模型, 用十二烷基硫酸钠聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳技术和表面增强激光解析电离飞行时间质谱技术在小鼠尿中检测到这两种标志物的存在。

Ni等[52]采用GC-MS和LC-MS技术, 结合主成分分析模式, 对雄性Wistar大鼠在不同时间点的尿液样本进行分析发现, 与健康对照组相比, 马兜铃酸肾毒性组大鼠尿液中的胱氨酸、半胱氨酸、同型半胱氨酸、蛋氨酸和丝氨酸等氨基酸含量紊乱, 反映了肾小管受损和细胞间质纤维化, 可作为肾病诊断的一个标准。

3 马兜铃酸的减毒方法 3.1 炮制中药炮制是我国特有的、具有传统特色的制药技术, 对药性和中医临床疗效有直接的影响, 其根本目的是“取利去害”, 即保证用药的安全有效[53, 54]。炒法和炙法等多种炮制方法自古便应用于马兜铃、细辛等毒性药材, 沿用至今并不断改良完善, 目前仍是含AAs中药最常用的减毒增效方法, 其关键工艺在于高温处理可使AAs发生降解、含量降低。因AAs的结构中含有羧基, 可与碱或强碱盐等反应而溶于水, 残余的碱液和马兜铃酸盐用水洗即可除去; 醋炙可使炮制品中残留而易于煎出的痕量马兜铃酸盐还原为难以被煎出的AAs, 以除去AAs或使AAs难以煎出[55]。这里列举5种常用马兜铃科中药的炮制减毒方法(表 2)。

| Table 2 Common processing methods of medicinal materials containing AAs |

马兜铃炮制古以焙制、炒制和炙制运用较多, 辅料炮制仅见酥炙一种, 现代多用蜜炙法, 以增强清肺降气, 止咳平喘, 清肠消痔之功效, 减少毒副作用[56]。例如, 对马兜铃果实的外果皮、内果皮、隔膜和种子4个部位的AAs研究, 并对其中的AAⅠ和AAⅡ进行了定量分析, 结果发现, 在种子中检测到的AAⅠ和AAⅡ的含量分别为840.17~2 293.44和14.44~131.68 μg·g-1, 在整个马兜铃果实中AAⅠ和AAⅡ的含量分别为253.92~1 206.04和28.52~50.35 μg·g-1, 而从外果皮、内果皮、隔膜中则未检测到AAⅠ和AAⅡ[57]。Li等[58]发现, 经蜜炙后, 马兜铃中AAⅠ、AAⅡ、马兜铃酸C、马兜铃酸D和7-羟基-马兜铃酸Ⅰ (7-OH AAⅠ) 5种马兜铃酸的含量下降了16.9%~50.6%。Yuan等[59]评估了马兜铃生品和蜜炙品的毒性作用, 生品和蜜炙品的半数致死量(LD50) 分别为34.1 ± 7.2和62.6 ± 8.0 g·kg-1·d-1, 蜜炙品的LD50约为生品的1.84倍。Yang等[60]对马兜铃的不同炮制方法进行了比较, 各炮制品中AAs含量下降比例按降序排列依次为: 碱制-醋制、碱制、蜜炙、盐炙、姜炙、炒焦和醋制, 其中碱制-醋制法可使马兜铃中的6种马兜铃酸的含量下降50.54%。

3.1.2 细辛《中国药典》自2005年版起将细辛的药用部位由原来的全草改为根和根茎入药, 这也得到了一些基础研究的论证。Xue等[61]对7批次细辛进行检测后发现, 细辛地下部分含有的AAⅠ含量为0.476~5.003 μg·g-1, 属于痕量; 而细辛地上部分的AAⅠ含量为5.953~71.187 1 g·g-1, 约为地下部分的40倍。Chen等[62]比较了清肺排毒汤、细辛水煎液及细辛70%甲醇提取液中AAⅠ的含量, 发现当细辛用量为6 g时, 3种样品中AAⅠ的含量分别为1.5、3.2和9.0 μg, 均低于《中国药典》中规定的每日最大30 μg的限量标准。细辛的传统炮制方法可分为两大类: 一类为炒、焙、炮等加热炮制; 另一类为加入酒或醋等辅料炮制[63]。Yan等[64]对细辛的10种炮制方法进行了考察, 发现所有炮制方法均可降低AAⅠ的含量, 并以炒焦炮制最优, 其中炒焦法对细辛中AAⅠ的去除率达到了60%以上。

3.1.3 青木香研究发现碳酸氢钠(NaHCO3)-醋酸法可除去青木香生品中85%以上的AAs, 用小鼠和大鼠进行毒理学实验, 测得生品饮片的LD50为146.45 g·kg-1, 青木香炮制品的LD50是青木香生品的5.78倍, 表明青木香经碱醋炮制工艺处理后, 毒性明显降低[65]。

3.1.4 关木通据文献记载, 清炒法、加辅料炒法、炙法、蒸法和煮法等多种炮制方法均可降低关木通中AAⅠ的含量, 并显著减轻对动物肾功能的损害, 在多种炮制方式中以醋炙法和碱炙法的研究最为深入。Pan等[66]用HPLC测定关木通生品及29种炮制品中AAⅠ的含量, 发现石灰水煮、石灰水蒸、甘草汁煮、黑豆汁煮、小苏打水煮及滑石粉炒6种方法制得的样品中AAⅠ的含量降低最明显, 可降低30%以上, 煮法较其他方法更好, 原因可能为煎煮法加热时间更长, 辅料中以分子或离子状态存在的成分可充分渗入到药材组织中并与AA发生反应, 以降低其含量。Li等[67]采用HPLC法测定不同关木通炮制品中AAⅠ的含量, 发现其中醋炙品中AAⅠ的含量约为1.01 mg·g-1, 其水浸出物与醇浸出物的含量相当, 是最佳炮制方法。另对关木通醋炙和碱炙技术进行了改进, 得到最佳实验条件是采用0.05 mol·L-1 NaHCO3溶液浸泡药材3次, 浸泡时间为24 h, 优化后的工艺可使马兜铃总酸去除率达83.74%[68]。

3.1.5 朱砂莲Ren等[69, 70]用蒸制、蜜炙、碱水炙和甘草汁炙4种方法对朱砂莲饮片进行炮制后, 采用HPLC法对生品和炮制品中AAⅠ的含量进行测定, 除蒸制组外, 其余3种炮制法均可起到降低AAI含量的作用, 其中以碱水炙法最佳, 生品中AAⅠ含量为2.439 4‰, 而碱水炙品含量则为0.160 8‰, 变化率可达93.41%。采用热板法和醋酸扭体法测试朱砂莲生品、蜜炙品、碱水炙品和甘草汁炙品水提物给药的小鼠, 发现3种炮制品的提取物均有明显的镇痛作用, 且以甘草汁炙品效果最佳。

3.2 配伍研究证实, 补益药中的黄芪、冬虫夏草、当归、甘草和啤酒花, 活血药中的丹参, 清热药中的牡丹皮、竹叶和黄连, 泻下药中的大黄, 温里药中的干姜和附子, 滋阴药中的生地黄、玄参和麦冬等, 均可与关木通、广防己和朱砂莲等配伍, 在煎煮过程中发生氧化、还原和分解等化学反应而降低马兜铃酸的含量; 配伍药材中的生物碱和金属离子可抑制毒性成分的溶出, 减轻其肾毒性和肝毒性等不良反应, 起到增强药效的作用[71-75]。针对AAs的毒性机制, 可以配伍活血化瘀中药, 同时配合补肾益气健脾药以补肾活血, 以达到扩张肾血管、增加肾血流量、促进纤维组织吸收和防治肾纤维化的目的[76]。Fang等[77]研究发现益肾软坚散可通过下调马兜铃酸钠盐所致的转化生长因子β (TGF-β1)、结缔组织生长因子和金属蛋白酶组织抑制物1的高表达, 拮抗AAs的致肾纤维化效应。其次, 使用具有钙拮抗作用的中药[78], 抑制肾小管上皮细胞的外钙内流, 对抗AAs升高细胞内游离钙离子浓度的作用, 防止肾小管上皮细胞凋亡。Ruan等[79]采用RP-HPLC比较当归四逆汤各拆方组与关木通中AAⅠ的含量, 测得当归四逆汤全方中AAⅠ含量最低, 含量约为关木通单方组的31.97%。

3.3 培育 3.3.1 传统育种在马兜铃科植物的人工栽培中, 药材中有效成分和有毒成分的积累会受到环境和气候等多种因素的影响。与其他减毒方法相比, 育种所需时间长、过程更加繁琐, 投入成本高, 但只要选育成功就有可能从源头上解决马兜铃酸的毒性问题。采用水超声处理辽细辛种子后, 种植出的细辛中的AAⅠ含量降低, 地下部分中的AAⅠ含量随月份的增长而不断降低, 由5月份的0.62×10-3%~1.68×10-3%降低至约9月份的0.09×10-3%~1.55×10-3%, 但不能被完全去除[80]。Cheng等[81]用田间试验研究了不同遮阴度对3年生北细辛中AAⅠ含量的影响, 结果发现在采收季节, 北细辛在50%、70%和90%遮阴度下AAⅠ的平均含量分别为0.256 28、0.259 88和0.261 08 mg·g-1, 含量差异不显著, 但50%遮阴度成本投入最低, 且可最大程度地降低细辛中AAⅠ的含量。

3.3.2 分子育种Schutte等[82]对马兜铃属4种植物进行研究, 发现AAⅠ起源于酪氨酸, 并转化成多巴胺和4-羟基苯乙醛, 缩合成为S-去甲乌药碱, 但其具体转化途径未知。Yang等[83]从马兜铃中扩增得到酪氨酸脱羧酶(tyrosine decarboxylase, TyrDC) 基因全长cDNA序列, 发现不同植物的酪氨酸脱羧酶之间普遍存在序列相似性, TyrDC是AAs生物合成途径中第1个酶的编码基因, 以TyrDC为靶基因进行基因敲除可能会阻断AAs的合成, 提高含AAs中药的安全性。

3.4 药物介入减毒研究发现, 通过药物介入来减弱AAs导致的肾毒性, 特别是天然药物在AAs减毒方面也发挥了不错的作用。Yu等[84]通过动物实验发现, 服用AAs大鼠的肾皮质与人的肾近端小管上皮细胞中TGF-β1、α-平滑肌肌动蛋白(α-sma) 和Snail mRNA蛋白表达明显上调, 而冬虫夏草能够有效地拮抗AAs诱导的组织纤维化, 其作用可能与抑制TGF-β1和Snail的表达有关。再如, 双香豆素和苯茚二酮均能抑制小鼠肾小管上皮细胞中高表达的醌氧化还原酶1 (NQO1) 的活性, 并使AAⅠ硝化还原而减弱了AAs导致的肾毒性; 当服用较高剂量的AAⅠ时, 用双香豆素预处理的小鼠存活率会显著增加[85]。Ding等[86]通过记录斑马鱼模型肾脏和红细胞循环的细微变化评价白藜芦醇(Resv) 和熊果酸(UA) 对肾脏的保护作用, 结果发现Resv和UA的治疗都可以减轻AA诱导的肾脏畸形并改善血液循环, 并有助于肾功能的恢复。另外, Wang等[87]发现白细胞介素-22可通过抑制细胞质核苷酸结合寡聚化域样受体蛋白3 (NOD-like receptor protein 3, NLRP3) 炎症小体的激活而显著减轻AAN对肾小管的损伤和AA诱导的肾纤维化和肾功能障碍。Hamano等[88]在AA肾病小鼠模型上进行了肾小管间质损伤的研究, 结果显示, 虽然早期应用小剂量达贝泊松α对红细胞压积影响不大, 但通过提高肾小管细胞存活率明显改善急性肾小管损伤和间质炎症, 有助于保存肾小管周围毛细血管和减少间质纤维化。

此外, 通过药物介入治疗的办法, 能够抑制AAs诱导的正常肾细胞凋亡和减小毒性[89-92]。例如, H2松弛素可通过激活磷脂酰肌醇-3-激酶/蛋白激酶B信号通路传导途径减少AAⅠ诱导的细胞凋亡; 硼替佐米能够显著减轻AAs诱导的肾功能不全和蛋白尿, 降低肾纤维化相关蛋白和肾损伤标志物等表达, 并在组织病理学水平上阻止肾纤维化的发生; 维生素C和维生素D可降低AAs诱导的H2O2水平升高和半胱氨酸天冬氨酸蛋白酶-3活性, 从而减轻AAs诱导的细胞毒性等。

3.5 其他此外, 结构改造法[93]、微生物转化[94]、分子印迹技术(MIT)[95]和使用抗氧化剂[96]等多种技术也用于AAs的减毒, 并取得了一定的成效和进展, 但由于这些方法的研究不深入, 故尚未得到广泛应用。

4 结语在我国, 含AAs的中药品种较多, 有的中药药用历史悠久, 是不少复方的重要组成, 用途涉及抗菌、抗肿瘤和保健等多方面。自“马兜铃酸事件”以来, 我国加强了对含AAs药物的风险管理措施, 但部分含AAs的中药仍缺乏明确的马兜铃酸限量使用标准和安全使用期限。并且, 对许多中药及其制剂中AAs的定性和定量、限量使用和毒理学等内容的研究尚不够深入而无法充分评估其风险, 这严重影响了含AAs中药的临床用药安全, 也引发了公众对含AAs中药的疑虑心理。

我国药用植物资源丰富, 寻找AAs含量高的中药替代品可作为一种可行的解决方法。同时, 应在中医药理论的指导下, 结合现代技术手段, 加强对含AAs中药的风险评估及质量评价, 制定合理的AAs限量标准, 并探索安全有效的AAs减毒方式, 以保障此类中药的临床用药安全。

作者贡献: 郭宁和王安琪主要负责文献的收集及论文的撰写; 赵雍、徐凌川、孙奕和梁爱华主要负责论文指导及稿件修改。

利益冲突: 所有作者声明本文无任何利益冲突。

| [1] |

Michl J, Ingrouille MJ, Simmonds MS, et al. Naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues and their toxicities[J]. Nat Prod Rep, 2014, 31: 676-693. DOI:10.1039/c3np70114j |

| [2] |

Balachandran P, Wei F, Lin RC, et al. Structure activity relationships of aristolochic acid analogues: toxicity in cultured renal epithelial cells[J]. Kidney Int, 2005, 67: 1797-1805. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00277.x |

| [3] |

Priestap HA. Minor aristolochic acids from Aristolochia argentina and mass spectral analysis of aristolochic acids[J]. Phytochemistry, 1987, 26: 518-529. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81447-8 |

| [4] |

Nagasawa H, Wu G, Inatomi H. Effects of aristoloside, a component of Guan-mu-tong (Caulis aristolochiae manshuriensis), on normal and preneoplastic mammary gland growth in mice[J]. Anticancer Res, 1997, 17: 237-240. |

| [5] |

Lemos VS, Thomas G, Filho JMB. Pharmacological studies on Aristolochia papillaris Mast. (Aristolochiaceae)[J]. J Ethnopharmacol, 1993, 40: 141-145. DOI:10.1016/0378-8741(93)90060-I |

| [6] |

Balachandran P, Wei F, Lin RC, et al. Structure activity relationships of aristolochic acid analogues: toxicity in cultured renal epithelial cells[J]. Kidney Int, 2005, 67: 1797-1805. DOI:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00277.x |

| [7] |

Yu XH, Guo X, Wang M, et al. Study on biopharmaceutical classification of aristolochic acids a in 17 Chinese patent medicines[J]. Chin Trad Patent Med (中成药), 2020, 42: 1596-1599. |

| [8] |

Gao Y, Xiao XH, Zhu XX, et al. Study and opinion on toxicity of aristolochic acid[J]. China J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2017, 42: 4049-4053. |

| [9] |

Vanherweghem JL, Depierreux M, Tielemans C, et al. Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis in young women: association with slimming regimen including Chinese herbs[J]. Lancet, 1993, 341: 387-391. DOI:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92984-2 |

| [10] |

Ng AWT, Poon SL, Huang MN, et al. Aristolochic acids and their derivatives are widely implicated in liver cancers in Taiwan and throughout Asia[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2017, 9: eaan6446. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aan6446 |

| [11] |

Nault JC, Letouzé E. Mutational processes, hepatocellular carcinoma: the story of aristolochic acid[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2019, 39: 334-340. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1685516 |

| [12] |

Chinese Academy of Sciences. Flora of the People's Republic of China (中国植物志)[M]. Vol 24. Beijing: Science Press, 1988.

|

| [13] |

Yun KY, Xu ZC, Song JY. Traditional Chinese medicine containing aristolochic acids and their detection[J]. Sci Sin Vit (中国科学: 生命科学), 2019, 49: 238-249. DOI:10.1360/N052018-00274 |

| [14] |

Zhu XX, Wang J, Liao S, et al. Synopsis of Aristolochia L. and Isotrema Raf. (Aristolochiaceae) in China[J]. Biodiver Sci (生物多样性), 2019, 27: 1143-1146. DOI:10.17520/biods.2019183 |

| [15] |

Liang AH, Gao Y, Zhang BL. Safety problems and countermeasures of traditional Chinese medicine containing aristolochic acids[J]. China Food Drug Administration Mag (中国食品药品监管), 2017, 11: 17-20. |

| [16] |

Lu J. Discussion on Chinese medicinal materials related to aristolochic acids[J]. Drug Standards China (中国药品标准), 2002, 3: 49-50. |

| [17] |

Tian JZ, Liang AH, Liu J, et al. Risk control of traditional Chinese medicines containing aristolochis acids (AAs) based on influencing factors of content of AAs[J]. China J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2017, 42: 4679-4686. |

| [18] |

Han JY, Xian Z, Zhang YS, et al. Systematic overview of aristolochic acids: nephrotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and underlying mechanisms[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2019, 10: 648. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2019.00648 |

| [19] |

Chen H, Cao G, Chen DQ, et al. Metabolomics insights into activated redox signaling and lipid metabolism dysfunction in chronic kidney disease progression[J]. Redox Biol, 2016, 10: 168-178. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2016.09.014 |

| [20] |

Arlt VM, Marie S, Schmeiser HH. Aristolochic acid as a probable human cancer hazard in herbal remedies: a review[J]. Mutagenesis, 2002, 17: 265-277. DOI:10.1093/mutage/17.4.265 |

| [21] |

Arlt VM, Stiborová M, Vom BJ, et al. Aristolochic acid mutagenesis: molecular clues to the aetiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy-associated urothelial cancer[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2007, 28: 2253-2261. DOI:10.1093/carcin/bgm082 |

| [22] |

Yue H, Chan W, Yu KJ, et al. Recent progress in quantitative analysis of DNA adducts of nephrotoxin aristolochic acid[J]. Sci China Ser B Chem, 2009, 52: 1576-1582. DOI:10.1007/s11426-009-0233-6 |

| [23] |

Stiborová M, Arlt VM, Schmeiser HH. DNA adducts formed by aristolochic acid are unique biomarkers of exposure and explain the initiation phase of upper urothelial cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18: 2144. DOI:10.3390/ijms18102144 |

| [24] |

Yang HY, Yang CC, Wu CY, et al. Aristolochic acid and immunotherapy for urothelial carcinoma: directions for unmet needs[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20: 3162. DOI:10.3390/ijms20133162 |

| [25] |

Schmeiser HH, Kucab JE, Arlt VM, et al. Evidence of exposure to aristolochic acid in patients with urothelial cancer from a Balkan endemic nephropathy region of Romania[J]. Environ Mol Mutagen, 2012, 53: 636-641. DOI:10.1002/em.21732 |

| [26] |

Stiborová M, Martínek V, Frei E, et al. Enzymes metabolizing aristolochic acid and their contribution to the development of aristolochic acid nephropathy and urothelial cancer[J]. Curr Drug Metab, 2013, 14: 695-705. DOI:10.2174/1389200211314060006 |

| [27] |

Couture A, Deniau E, Grandelaudon P, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of aristolctams[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2002, 12: 3557-3559. DOI:10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00794-1 |

| [28] |

Liu MC, Maruyama S, Mizuno M, et al. The nephrotoxicity of aristolochia manshuriensis in rats is attributable to its aristolochic acids[J]. Clin Exp Nephro, 2003, 7: 186-194. DOI:10.1007/s10157-003-0229-z |

| [29] |

Jelakovi B, Dika I, Arlt VM, et al. Balkan endemic nephropathy and the causative role of aristolochic acid[J]. Semin Nephrol, 2019, 39: 284-296. DOI:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2019.02.007 |

| [30] |

Chen CH, Dickman KG, Moriya M, et al. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109: 8241-8246. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1119920109 |

| [31] |

Wu F, Wang T. Risk assessment of upper tract urothelial carcinoma related to aristolochic acid[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2013, 22: 812-820. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1386 |

| [32] |

Chan W, Poon WT, Chan YW, et al. A new approach for the sensitive determination of DNA adduct of aristolochic acid Ⅱ by using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection[J]. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life, 2009, 877: 848-852. DOI:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.02.007 |

| [33] |

Pfau W, Schmeiser HH, Wiessler M. Aristolochic acid binds covalently to the exocyclic amino group of purine nucleotides in DNA[J]. Carcinogenesis, 1990, 11: 313-319. DOI:10.1093/carcin/11.2.313 |

| [34] |

Ivana B, Tobias K, Jian J, et al. Software tools and approaches for compound identification of LC-MS/MS data in metabolomics[J]. Metabolites, 2018, 8: 31. DOI:10.3390/metabo8020031 |

| [35] |

Cui L, Lu H, Lee YH. Challenges and emergent solutions for LC-MS/MS based untargeted metabolomics in diseases[J]. Mass Spectrom Rev, 2018, 37: 772-792. DOI:10.1002/mas.21562 |

| [36] |

Guo J, Yun BH, Upadhyaya P, et al. Multiclass carcinogenic DNA adduct quantification in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues by ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Anal Chem, 2016, 88: 4780-4787. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00124 |

| [37] |

Yun BH, Xiao S, Yao LH, et al. A rapid throughput method to extract DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues for biomonitoring carcinogenic DNA adducts[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 2017, 30: 2130-2139. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00218 |

| [38] |

Guo L, Wu H, Yue H, et al. A novel and specific method for the determination of aristolochic acid-derived DNA adducts in exfoliated urothelial cells by using ultra performance liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry[J]. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci, 2011, 879: 153-158. DOI:10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.11.035 |

| [39] |

Chan W, Zheng YF, Cai ZW. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of the DNA adducts of aristolochic acids[J]. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom, 2007, 18: 642-650. DOI:10.1016/j.jasms.2006.11.010 |

| [40] |

Chan W, Yue H, Poon WT, et al. Quantification of aristolochic acid-derived DNA adducts in rat kidney and liver by using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry[J]. Mutat Res, 2008, 646: 17-24. DOI:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.012 |

| [41] |

Yun BH, Bellamri M, Rosenquist TA, et al. Method for biomonitoring DNA adducts in exfoliated urinary cells by mass spectrometry[J]. Anal Chem, 2018, 90: 9943-9950. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02170 |

| [42] |

Romanov V, Sidorenko V, Rosenquist TA, et al. A fluorescence-based analysis of aristolochic acid-derived DNA adducts[J]. Anal Biochem, 2012, 427: 49-51. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2012.03.027 |

| [43] |

Li WW, Hu Q, Chan W. Mass spectrometric and spectrofluorometric studies of the interaction of aristolochic acids with proteins[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 15192. DOI:10.1038/srep15192 |

| [44] |

Schmeiser HH, Nortier JL, Singh R, et al. Exceptionally long-term persistence of DNA adducts formed by carcinogenic aristolochic acid I in renal tissue from patients with aristolochic acid nephropathy[J]. Int J Cancer, 2014, 135: 502-507. DOI:10.1002/ijc.28681 |

| [45] |

Grollman AP, Shibutani S, Moriya M, et al. Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007, 104: 12129-12134. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0701248104 |

| [46] |

Trnacevic S, Nislic E, Trnacevic E, et al. Early screening of Balkan endemic nephropathy[J]. Mater Sociomed, 2017, 29: 207-210. DOI:10.5455/msm.2017.29.207-210 |

| [47] |

Lin CE, Chang WS, Lee JA, et al. Proteomics analysis of altered proteins in kidney of mice with aristolochic acid nephropathy using the fluorogenic derivatization-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method[J]. Biomed Chromatogr, 2017, 32: e4127. |

| [48] |

Leung EM, Chan W. Comparison of DNA and RNA adduct formation: significantly higher levels of RNA than DNA modifications in the internal organs of aristolochic acid-dosed rats[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 2015, 28: 248-255. DOI:10.1021/tx500423m |

| [49] |

Zhao Y, Chan CK, Chan KKJ, et al. Quantitation of N6-formyl-lysine adduct following aristolochic acid exposure in cells and rat tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with stable isotope-dilution method[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 2019, 32: 2086-2094. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00272 |

| [50] |

Mantle P, Modalca M, Nicholls A, et al. Comparative 1H NMR metabolomic urinalysis of people diagnosed with Balkan endemic nephropathy, and healthy subjects, in Romania and Bulgaria: a pilot study[J]. Toxins, 2011, 3: 815-833. DOI:10.3390/toxins3070815 |

| [51] |

Huang F, Clifton J, Yang XL, et al. SELDI-TOF as a method for biomarker discovery in the urine of aristolochic-acid-treated mice[J]. Electrophoresis, 2009, 30: 1168-1174. DOI:10.1002/elps.200800548 |

| [52] |

Ni Y, Su M, Qiu Y, et al. Metabolic profiling using combined GC-MS and LC-MS provides a systems understanding of aristolochic acid-induced nephrotoxicity in rat[J]. Febs Lett, 2007, 581: 707-711. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.036 |

| [53] |

Yang M, Zhong LY, Xue X, et al. Inheritance and innovation of traditional processing technology of Chinese medicine[J]. China J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2016, 41: 357-361. |

| [54] |

Tang TY. A preliminary study on the history of processing theory of Chinese materia medica (the first part of Qing Dynasty)[J]. Mod Chin Med (中国现代中药), 2018, 20: 230-238. |

| [55] |

Wang ZM, You LS, Jiang X, et al. Methodological study on the removal of toxic components from Aristolochia manshuriensis by processing technology[J]. China J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2005, 30: 1243-1246. |

| [56] |

Dong LS, Shang M, Cai SQ. A study on the varieties, origin and processing history of Aristolochiae Fructus[J]. China J Chin Materia Med (中国中药杂志), 2003, 28: 33-37. |

| [57] |

Mao WW, Gao W, Liang ZT, et al. Characterization and quantitation of aristolochic acid analogs in different parts of Aristolochiae Fructus, using UHPLC-Q/TOF-MS and UHPLC-QqQ-MS[J]. Chin J Nat Med, 2017, 15: 392-400. |

| [58] |

Li ZH, Yang B, Yang WL, et al. Effect of honey-toasting on the constituents and contents of aristolochic acid analogues in Aristolochiae Fructus[J]. J Chin Med Mater (中药材), 2013, 36: 538-541. |

| [59] |

Yuan JB, Huang Q, Ren G, et al. Acute and subacute toxicity of the extract of Aristolochiae Fructus and honey-fried Aristolochiae Fructus in rodents[J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2014, 37: 387-393. DOI:10.1248/bpb.b13-00736 |

| [60] |

Yang B, Li ZH, Yang WL, et al. The effect of various drug processing technologies on the contents of aristolochic acid analogues in Aristolchiae Fructus[J]. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res (时珍国医国药), 2012, 23: 2553-2555. |

| [61] |

Xue Y, Tong XH, Wang F, et al. Analysis of aristolochic acid A from the aerial and underground parts of Asarum by UPLC-UV[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2008, 43: 221-223. |

| [62] |

Chen YJ, Wang W, Xiao HB. Monitoring and quantitative analysis of trace aristolochic acid Ⅰ in a Qing-Fei-Pai-Du decoction using liquid chromatographymass spectrometry[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2020, 55: 1903-1907. |

| [63] |

Qiang XJ, Yin D, Zhu ZH. History and research progress of Asari Radix et Rhizoma processing[J]. Chin J Inf Tradit Chin Med (中国中医药信息杂志), 2017, 24: 130-132. |

| [64] |

Yan JY, Wang YQ, Wang Y, et al. Research on reducing safrole and aristolochic acid A in Asari Radix et Rhizoma based on different processing techniques[J]. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs (中草药), 2015, 46: 216-220. |

| [65] |

Jiang X, Li L, Wang WH, et al. Toxicologically studies of raw radix aristolochiae and it's processed product[J]. Chin Remed Clinic (中国药物与临床), 2006, 6: 485-487. |

| [66] |

Pan JH, Yan GJ, Song J. The determination of aristolochic acid A in different processed Aristolochia Manshuriensis and the test of influence about renal function in rats[J]. J Chin Med Mater (中药材), 2010, 33: 1228-1233. |

| [67] |

Li TF, Li LK, Zhang ML, et al. Determination of aristolochic acid in Aristolochia Manshuriensis with different processing methods by RP-HPLC[J]. Chin Med Her (中国医药导报), 2015, 12: 14-17. |

| [68] |

He M, Zhang J, Yang L. Application of RBF and RSM in optimizing the processing conditions of Manchurian Dutchmanspipe stem with alkali[J]. Her Med (医药导报), 2014, 33: 914-916. |

| [69] |

Ren HZ. Determination of the content of aristolochic acid-ain processed Aristolochia cinnabarine by HPLC[J]. Asia-Pacific Tradit Med (亚太传统医药), 2015, 11: 23-25. |

| [70] |

Ren HZ, Lin HX, Xiao LX. Comparatively study on the analgesic effect of the raw and processed Aristolochia Cinnabarine root tuber[J]. Asia-Pacific Tradit Med (亚太传统医药), 2016, 12: 18-20. |

| [71] |

Quan SJ, Ding J, Wang HD. Effect of Chinese traditional medicine of nourishing Yin and nourishing blood on aristolochic acid A content of Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis[J]. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med (辽宁中医杂志), 2009, 36: 1766-1767. |

| [72] |

Wang WW, Zhang JY, Cheng J. Effect of Salvia Miltiorrhiza on renal pathological change and expression of ACE and ACE2 in rats with aristolochic acid induced nephropathy[J]. Chin J Integrat Tradit West Nephrol (中国中西医结合肾病杂志), 2009, 10: 109-112. |

| [73] |

Wu JH, Zhang ZH, Lv YJ, et al. Study on Rhizoma Coptidis decreasing the content of aristolochic acid A by HPLC[J]. J Hubei Univ Chin Med (湖北中医药大学学报), 2012, 14: 39-42. |

| [74] |

Liu YQ, Zhao HH, Hou N, et al. Determination of aristolochic acid A in decoction of Caulis Aristolochiae Manshuriensis and its combination with other Chinese herbal by reversed phase high perfarmance liquid chromatography[J]. Chin J Anal Chem (分析化学), 2006, 34: 161-164. |

| [75] |

Zhang YC, Wang JC, Pan JH, et al. Discussion on mechanism of attenuating toxicity and saving effect of Aristolochia Manshuriensis compatibility with processed Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata and Zingiberis Rhizoma based on'Fuyang Buxu'theory[J]. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Form (中国实验方剂学杂志), 2017, 23: 7-12. |

| [76] |

Zhang MZ, Zhang DN. Kidney-nourishing and blood-activating therapy for aristolochic acid nephropathy in 65 cases[J]. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med (上海中医药杂志), 2003, 37: 30-32. |

| [77] |

Fang J, Chen YP, Yang YF, et al. Antagonistic effect of Yishen Ruanjian San contained serum against aristolochic acid in antagonizing human renal interstitial fibroblasts[J]. Chin J Integrat Tradit West Med (中国中西医结合杂志), 2004, 24: 811-815. |

| [78] |

Chen JL, Wu YH, Deng YY, et al. Protective effect of Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae on the aristolochic acid induced renal tubular epithelial cell injury[J]. Chin J Integrat Tradit West Nephrol (中国中西医结合肾病杂志), 2005, 6: 445-448. |

| [79] |

Ruan YP, Hu XM, Zhao YM. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine compatibility on aristolochic acid content in Danggui Sini Decoction[J]. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med (中华中医药学刊), 2012, 30: 549-551. |

| [80] |

Sun XY, Sun QS, Jia LY. Determination of the contents of aristolochic acid A in growthing Asarum heterotropoides Fr. Schmidt var. mandshuricum (Maxim.) Kitag. planted after the pretreatment of the seeds by HPLC[J]. J Shenyang Pharm Univ (沈阳药科大学学报), 2009, 26: 299-302. |

| [81] |

Cheng Z, Hu YS. Effect of shade on the content of aristolochic acid A in Asarum heterotropoides[J]. Guizhou Agri Sci (贵州农业科学), 2014, 42: 69-71. |

| [82] |

Schutte HR, Orban U, Mothes K. Biosynthesis of aristolochic acid[J]. Eur J Biochem, 1967, 1: 70-72. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1967.tb00045.x |

| [83] |

Yang RY, Zeng QP. Cloning, sequencing and homology analysis of tyrDC in Aristolochia debilis[J]. J Guangzhou Univ of Chin Med (广州中医药大学学报), 2005, 2: 152-159. |

| [84] |

Yu M, Man YL, Chen MH, et al. Hirsutella sinensis inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation to block aristolochic acid-induced renal tubular epithelial cell transdifferentiation[J]. Hum Cell, 2020, 33: 79-87. DOI:10.1007/s13577-019-00306-9 |

| [85] |

Chen M, Gong LK, Qi XM, et al. Inhibition of renal NQO1 activity by dicoumarol suppresses nitroreduction of aristolochic acid I and attenuates its nephrotoxicity[J]. Toxicol Sci, 2011, 122: 288-296. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfr138 |

| [86] |

Ding YJ, Sun CY, Wen CC, et al. Nephroprotective role of resveratrol and ursolic acid in aristolochic acid intoxicated zebrafish[J]. Toxins (Basel), 2015, 7: 97-109. DOI:10.3390/toxins7010097 |

| [87] |

Wang SF, Fan JJ, Mei XB, et al. Interleukin-22 attenuated renal tubular injury in aristolochic acid nephropathy via suppressing activation of NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 2277. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02277 |

| [88] |

Hamano Y, Aoki T, Shirai R, et al. Low-dose darbepoetin alpha attenuates progression of a mouse model of aristolochic acid nephropathy through early tubular protection[J]. Nephron Exp Nephrol, 2010, 114: e69-81. |

| [89] |

Xie XC, Zhao N, Xu QH, et al. Relaxin attenuates aristolochic acid induced human tubular epithelial cell apoptosis in vitro by activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway[J]. Apoptosis, 2017, 22: 769-776. DOI:10.1007/s10495-017-1369-z |

| [90] |

Zeniya M, Mori T, Yui N, et al. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib attenuates renal fibrosis in mice via the suppression of TGF-β1[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 13086. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-13486-x |

| [91] |

Wu TK, Wei CW, Pan YR, et al. Vitamin C attenuates the toxic effect of aristolochic acid on renal tubular cells via decreasing oxidative stress-mediated cell death pathways[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2015, 12: 6086-6092. DOI:10.3892/mmr.2015.4167 |

| [92] |

Wu T, Pan Y, Wang H, et al. Vitamin E (α tocopherol) ameliorates aristolochic acidinduced renal tubular epithelial cell death by attenuating oxidative stress and caspase3 activation[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2018, 17: 31-36. |

| [93] |

Priestap HA, Barbieri MA. Conversion of aristolochic acid I into aristolic acid by reaction with cysteine and glutathione: biological implications[J]. J Nat Prod, 2013, 76: 965-968. DOI:10.1021/np300822b |

| [94] |

Liu XX, Wu XF, Pan Y, et al. Analysis of aristolochic acid derivates in Aristolochia debilis and its fermented product by HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS[J]. Chin J Nat Med, 2010, 8: 456-460. |

| [95] |

Xiao Y, Xiao R, Tang J, et al. Preparation and adsorption properties of molecularly imprinted polymer via RAFT precipitation polymerization for selective removal of aristolochic acid I[J]. Talanta, 2017, 162: 415-422. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2016.10.014 |

| [96] |

Li WW, Chan CK, Wong YL, et al. Cooking methods employing natural anti-oxidant food additives effectively reduced concentration of nephrotoxic and carcinogenic aristolochic acids in contaminated food grains[J]. Food Chem, 2018, 264: 270-276. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.052 |

2020, Vol. 56

2020, Vol. 56