2. 河南大学护理与健康学院, 河南 开封 475000;

3. 漯河医学高等专科学校, 河南 开封 475000

2. School of Nursing and Health, Henan University, Kaifeng 475000, China;

3. Luohe Medical College, Luohe 462002, China

随着我国“全面两孩”政策的开放, 高龄和高危产妇增多, 妊娠期用药往往不可避免, 妊娠期药物的系统评价结果显示, 60%~90%妊娠期妇女需要使用药物, 平均用药2~4种, 最多达8种[1]。其中约79%孕妇服用过对胎儿影响不明的药物, 增加了自发流产、早产和低体重儿的发生[2]。因此, 如何有效筛查生殖毒性药物, 对于妊娠期妇女安全用药必不可少。通常生殖毒性药物的测定方法包括临床病例回顾、实验动物模型和细胞模型的筛选, 但是这些方法都存在一些弊端, 如通过患者用药回访查找生殖毒性药物, 所需样本量较大, 回访时间较长, 存在回忆偏差, 且药物不良反应已经发生。而动物模型成本高昂, 需要考虑动物福利等问题。此外, 由于种属差异性问题, 动物实验的结果不能完全替代药物在人体的药理作用。细胞模型也可用于药物筛选[3], 但其丧失了组织、细胞发育的微环境, 破坏了组织和器官的结构, 不利于对整体胚胎发育的毒理学分析。因此, 寻求一种简便、灵敏、准确、经济的妊娠期药物筛选模型在所难免。

近年来, 由于干细胞重编程技术和体外三维培养策略的发展, 诱导多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cells, iPSCs)及其诱导产物逐渐成为筛选药物的新兴手段。iPSCs是通过特定基因转染或小分子化合物诱导等方式, 使正常体细胞重编程为胚胎干细胞(embryonic stem cells, ESCs)样的多潜能细胞[4]。相较ESCs, iPSCs取材方便, 成纤维细胞[5]、外周血细胞[6]、脂肪干细胞[7]和尿上皮细胞[8]都可用来制备iPSCs。此外, 人源iPSCs规避了伦理学问题和物种差异性问题, 在药物筛选, 尤其是生殖毒性药物筛选方面有巨大临床应用潜力。近期Lauschke等[9]利用人iPSCs筛查妊娠期药物, 但该实验仅测定iPSCs及其衍生的心肌细胞的药物毒理反应, 未对胚胎发育整体的药物作用进行研究。

本研究利用米非司酮(mifepristone, RU486)为实验药物, 以人类iPSCs培养的拟胚体(embryoid bodies, EBs)作为研究对象, 着眼于分析米非司酮对早期胚胎发育、细胞凋亡数和不同胚层分化的影响, 制定出具体流产药物筛选模型的评估标准。希望未来可用于临床I期前药物筛选或成分不明药物的流产不良反应的检测, 为妊娠期妇女安全用药提供指导。

材料与方法iPSCs的准备 提前一天将Matrigel基底膜基质(BD公司, 354277)从-80℃冰箱取出并放置在铺满碎冰的泡沫盒中, 4℃冰箱过夜融化。次日, 预冷枪头备用。将12 mL DMEM/F12培养基(Gibco公司, C11330500BT)转移至15 mL离心管内, 随后迅速加入150μL Matrigel基质胶混匀(使用冰冻后的枪头), 全过程冰上操作。混匀后滴加入6孔板中, 每孔2 mL, 室温下放置5~7 h, 待用。

本研究的iPSCs (购自中国科学院, 编号UE017C1)是由尿上皮细胞重编程而来。首先将2只冻存的iPSCs从液氮中取出, 37℃水浴融化, 然后将细胞悬液转移至15 mL离心管内, 逐滴加入已预热过的5 mL DMEM/F-12培养基, 200×g离心5 min, 弃去上清。再用2 mL mTeSRTM 1完全培养基(Stemcell公司, 85850)轻轻将细胞重悬, 制成混悬液。弃去之前包被6孔板所用的Matrigel, 然后将细胞悬液接种至此6孔板中, 注意勿损伤底部的基质膜。随后放入37℃、5%CO2、95%湿度的CO2培养箱(Phcbi公司, MCO-170M UVL-PC)中培养。

拟胚体的培养 通过三维悬浮培养的方式, iPSCs在体外可以快速聚集成EB, EB类似于早期胚胎组织, 具有发育成三胚层的潜力。培养过程如下: 每日更换iPSCs培养基, 待iPSCs克隆团长到每孔70%~80%时(培养4~5天), 用0.5 mmol·L-1 EDTA消化液(Life Technologies公司, 15575020)直接消化细胞, 37℃孵育5~8 min后, 弃去消化液即终止消化后。用含y-27632诱导因子(Stemcell公司, 72302)的拟胚体形成培养基(StemdiffTM cerebral organoid basal medium-1, Stemcell公司, 08572;Supplement A, Stemcell公司, 08574)轻轻吹打重悬iPSCs, 制成混悬液, 用血小板计数器进行细胞计数, 调整细胞浓度为每毫升104~105个左右。将处理后的iPSCs接种至超低黏附U型底96孔板中, 每孔100μL。次日, 每孔再添加75μL新鲜拟胚体培养基(不含y-27632因子)。每日半量换液, 体外培养3~4天后形成大小均匀的细胞团, 即为EBs。

拟胚体的继续分化 若对类皮质进行观察, 需要添加特异性的神经信号分子等诱导剂促使EBs向神经系统发育。EBs培养5天后, 用灭菌的巴氏吸管将EBs吸入到低黏附6孔板内, 每孔加入1.5 mL神经上皮诱导培养基(StemdiffTM cerebral organoid basal medium-1, Stemcell公司, 08572;Supplement B, Stemcell公司, 08575), 诱导培养48 h后。更换2 mL神经上皮扩大培养基(StemdiffTM cerebral organoid basal medium-2, Stemcell公司, 08573;Supplement C, Stemcell公司, 08576;Supplement D, Stemcell公司, 08577), 随后放入37℃、5%CO2、平衡湿度的CO2培养箱中, 培养96 h后。更换2~4 mL大脑皮质成熟培养基(StemdiffTM cerebral organoid basal medium-2, Stemcell公司, 08573;Supplement E, Stemcell公司, 08578), 每隔3~4天换液, 必要时培养至50天左右。

浓度选择及实验分组 目前临床指南推荐终止早期妊娠的药物是米非司酮和米索前列醇, 尤其是米非司酮对早期胚胎发育尤为敏感[10]。本研究米非司酮(Sigma公司, M8046)又名RU486, 规格100 mg, 以无水乙醇为溶剂溶解米非司酮。利用SPSS软件的回归模型计算米非司酮暴露EBs的半数致死浓度(lethal dose, 50%, LD50), 以倒置显微镜下EBs体积固缩、球体破裂和周围散在分布的死亡细胞增多为死亡观察指标。数据显示LD50为31.70μg·mL-1(95%CI: 18.98~44.35μg·mL-1)。本研究根据LD50和米非司酮浓度梯度预实验的结果, 最终确定本实验中米非司酮用量为低浓度(10μg·mL-1)和高浓度(20μg·mL-1)。

挑选外观大小均匀的EBs进行培养, 2天后开始加药。以米非司酮用药浓度的不同, 将其分成3组: ①低浓度组: 将EBs移入含有10μg·mL-1米非司酮的拟胚体培养基中培养; ②高浓度组: EBs移入含有20μg·mL-1米非司酮的拟胚体培养基培养; ③对照组: 将EBs移入不含有米非司酮的拟胚体培养基培养。为平衡无水乙醇作为溶剂对EBs的影响, 根据米非司酮加入量不同分别加入相应体积的无水乙醇。每天半量换液, 观察并定期收集EBs样本。

TUNEL法检测细胞凋亡 末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶介导的dUTP缺口末端标记测定法[terminal dexynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling, TUNEL]是检测细胞凋亡的常用而精准的方法。本实验利用TUNEL细胞凋亡检测试剂盒(Solarbio公司, T2190)检测细胞凋亡。具体步骤如下: 分别收集第5、8和11天的3个组别的EBs样本, 用4%多聚甲醛-磷酸缓冲盐溶液(phosphate buffer saline, PBS)固定30 min, 用0.01 mol·L-1 PBS缓冲液洗涤3次, 每次5 min, 再换30%蔗糖溶液沉降EBs, 24 h后, 用冰冻切片机(Leica公司, CM1950)切片, 厚度约12~15μm, 备用。然后用PBS冲洗切片3次, 每次5 min。每样品滴加20μL末端氧核苷酸转移酶反应液, 同时每组样品滴加20μL PBS作为阴性对照, 37℃孵育1 h, 用PBS洗3次, 每次5 min, 洗掉反应液。每样本加入20μL链霉亲和素, 室温孵育5 min, 用PBS冲洗, 最后用65%甘油-PBS溶液封片, 荧光显微镜(Olympus公司, BX53)下观察并采集图像。

DAPI法检测凋亡小体 4', 6-二脒基-2-苯基吲哚(4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, DAPI)可对细胞核进行非特异性染色, 用于显示细胞凋亡小体, 或衬染组织和器官。配制65%甘油-PBS溶液-DAPI (1∶1 000, Solarbio公司, C0060)的封片剂封片。

免疫荧光染色法检测 利用免疫荧光染色对EBs胚层和神经细胞发育进行观察, 本实验分别选用性别决定基因高迁移率组蛋白-2 (sex determining region Y-box 2, SOX2)标记胚胎干细胞和神经干细胞、Nestin标记外胚层细胞、CXCR4标记中胚层细胞、FoxA2标记内胚层细胞、Neu N标记神经元和GFAP标记神经胶质细胞。具体过程如下: 将切片从-20℃冰箱中取出, 室温下放置15~20 min, 切片复温后, 用0.01 mol·L-1 PBS洗3次, 每次5 min, 加入一抗, 放于4℃冰箱孵育过夜。PBS洗3次, 每次5 min, 加入二抗, 室温下避光孵育1.5~3 h, 用PBS洗3次, 每次5 min。最后用65%甘油加DAPI封片。荧光显微镜(Olympus公司, BX61)下观察并采集图片。所用一抗分别为: 鼠单克隆Nestin抗体(1∶1 200, Stemcell公司, 60091)、鼠单克隆Neu N抗体(1∶100, Millipore公司, MAB377)、鼠单克隆胶质纤维酸性蛋白(glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP)抗体(1∶200, Santa公司, SC33673)、兔单克隆C-X-C趋化因子受体4型(C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, CXCR4)抗体(1∶250, Abcam公司, ab124824)、兔单克隆FoxA2抗体(1∶200, Abcam公司, ab108422)、兔多克隆SOX2抗体(1∶200, Abcam公司, ab97959)和兔多克隆cleaved caspase-3抗体(1∶200, Abcam公司, ab13847)。一抗稀释液以1%牛血清白蛋白(bovine serum albumin, BSA)、0.3% Triton-X100和0.01 mol·L-1 PBS配制。二抗分别为Alexa Fluro 488羊抗兔IgG (1∶400, Invitrogen公司, A11034)和Alexa Fluro 568羊抗鼠IgG (1∶600, Invitrogen公司, A11031)。二抗稀释液以0.1%Triton-X100和0.01 mol·L-1 PBS配制。

指标测量与统计学分析 收集图片, 利用Image J1.48软件对免疫荧光染色图片进行数据处理。以EBs直径、细胞凋亡率、SOX2阳性细胞的密度、Nestin和CXCR4阳性细胞有效分化率为测量指标。参数公式分别为: ① EBs直径(μm, 倒置显微镜下测量); ②细胞凋亡率(%)=TUNEL阳性细胞数/细胞总数×100%;③ SOX2阳性细胞密度(百个/平方毫米)=SOX2阳性细胞数/观测面积; ④胚层细胞分化率(%)=阳性细胞数/细胞总数×100%(如外胚层源性Nestin和中胚层源性CXCR4阳性细胞)。使用SPSS 21软件对所得结果进行统计, 测量所得的数据利用单因素方差分析和卡方检验进行分析。结果采用均值±标准差(x±s)表示, P < 0.05时为差异具有统计学意义。

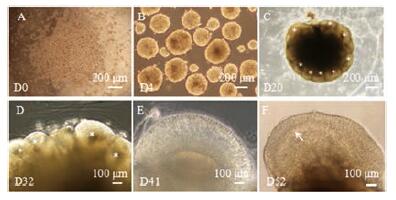

结果 1 正常拟胚体和类皮质的发育倒置显微镜下, iPSCs散在分布, 30 min内在无血清培养基中发生快速聚集(图 1A), 培养第4天, iPSCs聚集成三维球体即EBs, 高倍镜下观察到EBs边界清晰, 呈半透明环状, 中心部较黑(图 1B)。随后将EBs包埋于Matrigel基质胶中进行神经诱导培养, 第20天, EBs外围形成数个玫瑰花环状结构(neural rosettes, NR)的芽突, 类似神经管的发育。此时, 原始皮质类器官的形态初步可见(图 1C)。第32天, 类器官表面的NR结构有一部分会融合或退化, 约4~5个发育成大脑类皮质(图 1D)。第41天时, 类器官表面出现连续的放射状结构(图 1E)。第52天时, 类器官中放射状的结构增厚, 且具有层次化分布的特征(图 1F)。作者团队基于拟胚体的三胚层细胞分化、类皮质器官中神经干细胞发生、神经元和胶质细胞分化以及神经纤维再生等方面的研究, 成功证明了此方法培养的拟胚体和类器官类似于早期胚胎和大脑皮质[11, 12]。

|

Figure 1 Development of embryoid bodies (EBs) and cerebral organoids (under inverted microscope).A: The dissociated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) rapidly started to gather into iPS clones; B: At day 4 (D4), iPSCs accumulated continuously into three dimensional EBs, and EBs showed a smooth surface and translucent ring with dark center at high magnification; C: After neural induction, several rosettes (*) appeared in the periphery of EBs, and the primary organoids was visible at day 20 (D20);D, E: Some rosettes on the surface of cultivation would degenerate, and only a few developed into normal cerebral organoids with radial structures (↑); F: At day 52 (D52), cerebral organoids had typically cerebral lamination (↑).Scale bar, 200μm (A-C) and 100μm (D-F) |

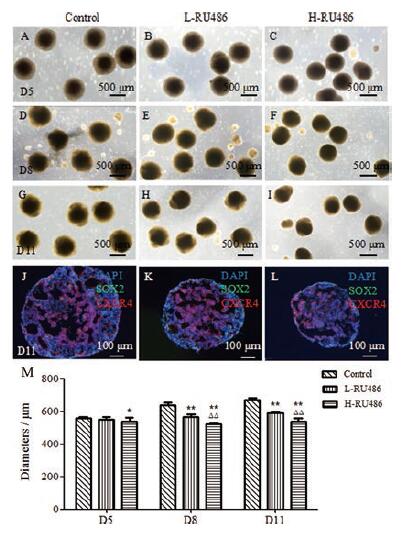

对EBs的生长动力学参数进行观察, 包括EBs直径、面积和体积, 旨在探讨该化学物质对胚胎的毒性作用[13]。随着体外培养时间的增加, EBs体积逐渐增大, EBs内部出现囊性结构。体外培养第5天, 对照组、低浓度和高浓度组间EBs直径变化不显著(图 2A~C)。培养第8天, 三组间EBs直径差异显著, 对照组EBs直径约为(636.73±19.48)μm, 低浓度组EBs直径约为(564.74±15.95)μm, 高浓度组EBs直径约为(522.65±6.03)μm (图 2D~F)。其中, 高浓度组EBs直径比对照组缩小约17.92%(P < 0.01, 图 2M)。第11天, 对照组EBs直径约为(670.68±11.73)μm, 低浓度组EBs直径约为(591.19±6.05)μm, 高浓度组EBs直径约为(538.92±18.55)μm (图 2G~L)。其中, 高浓度组EBs直径比对照组缩小约19.64%(P < 0.01, 图 2M)。综上, 米非司酮的用药浓度与EBs直径大小具有相关性, 随着用药浓度增加, EBs直径减小。当EBs直径缩小18%以上时, 可作为流产药物筛选的一个重要指标。

|

Figure 2 The changes of EBs' diameters after exposure to mifepristone.A-C: Under inverted microscope, at D5, no significant difference of EBs'size was found among there group; D-I: At days 8 and 11 (D8 and D11), EBs'diameters of the experimental groups were smaller than control group; J-L: Immunofluorescent double labeling with SOX2 (green) and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4(CXCR4, red) were used to observe EBs, EBs' diameters were remarkably reduced after mifepristone treatment at day 11 (D11).Inside of EBs, net like structure can be found.Scale bar, 500 μm(A-I) and 100 μm (J-L); M: The histogram and statistical analyses of EBs' diameter at days 5, 8, and 11 (D5, 8, and 11).n=5, x ± s.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control group; △△P < 0.01 vs L-RU486 group |

细胞凋亡是细胞主动激活的程序性死亡过程, 凋亡早期出现细胞核固缩, 染色加深, 或核呈新月形聚集于核膜一侧, 凋亡细胞晚期形成凋亡小体, 即细胞膜包裹胞质、核碎片及细胞器的泡状小体。DAPI染色结果显示, 培养5天后, 米非司酮暴露组凋亡小体逐渐增多(P < 0.05, 图 3A~C)。此外, TUNEL法也可以检测细胞凋亡, 其原理是通过标记DNA断裂的3'-OH末端来检测凋亡细胞。作者发现米非司酮用药组中TUNEL阳性细胞细胞核呈片状分布, 细胞排列紊乱。体外培养第5天, 对照组、低浓度和高浓度组间细胞凋亡数存在统计学差异(P < 0.01, 图 3D~F、M), 且与DAPI染色结果相比, TUNEL阳性细胞凋亡数偏高, 敏感度更高。培养第8天, 三组间EBs内部细胞凋亡率差异显著。对照组细胞凋亡率约为(26.66±5.01)%, 低浓度组细胞凋亡率约为(48.62±8.90)%, 高浓度组细胞凋亡率约为(63.36±7.40)%(图 3G~I)。其中高浓度组比对照组细胞凋亡率增加43.60%(P < 0.01, 图 3M)。第11天时, 对照组EBs细胞凋亡率约为(38.56±4.70)%, 低浓度组EBs细胞凋亡率约为(57.62±0.80)%, 高浓度组EBs细胞凋亡率约为(82.15±7.73)%(图 3J~L)。其中, 高浓度组比对照组细胞凋亡率增加53.07%(P < 0.01, 图 3M)。总之, 米非司酮暴露可以导致细胞凋亡, 其凋亡率增加44%以上, 也是流产药物的筛选重要指标。

|

Figure 3 Cell apoptosis in EBs after exposure to mifepristone.A-C: With DAPI staining, many apoptotic bodies were found after mifepristone exposure, such as cell contraction, chromatin aggregation, and broken chromosomes.The number of apoptosis cells increased with mifepristone concentration increasing; D-L: The results of TUNEL staining were consistent with DAPI staining.The number of TUNEL positive cells significantly increased in experimental groups.Scale bar, 20 μm (A-L); M: The histogram and statistical analyses of EBs' cell apoptosis on the exposure of mifepristone at days 5, 8, and 11 (D5, 8, and 11);n=5, x ± s.*P < 0.0 5, **P < 0.01 vs control group; △△P < 0.01 vs L-RU486 group |

EBs是多种类型细胞聚合的三维球体结构, 根据不同细胞间作用力的强弱, 自发地分化出三胚层结构[14]。选用Nestin标记外胚层中神经干细胞, 利用膜蛋白CXCR4标记中胚层细胞, 中胚层是心脏和血管等组织的发育原基。FoxA2可以标记内胚层细胞, 内胚层是肝、胰等消化腺以及消化管和呼吸道上皮的生发原基。此外, 利用SOX2标记胚胎干细胞、Neu N标记成熟神经元、GFAP标记星形神经胶质细胞。

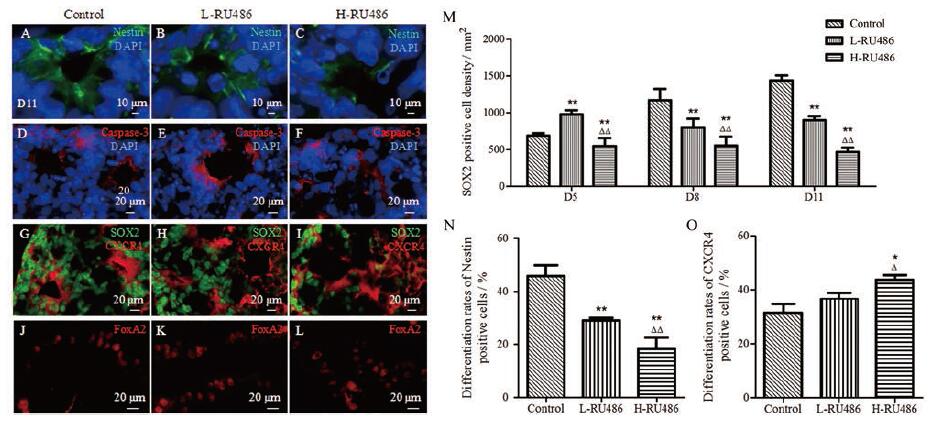

结果显示, 米非司酮可以抑制胚胎干细胞增殖, 抑制外胚层分化, 促进中胚层发育。① SOX2阳性胚胎干细胞分化: SOX2阳性细胞密度随着米非司酮用药浓度增加而减少。体外培养第11天, EBs外围分布着大量未分化的SOX2阳性细胞。对照组SOX2阳性细胞密度约(14.35±0.69)百个/mm2, 低浓度组SOX2阳性细胞密度约(8.99±0.51)百个/mm2, 高浓度组SOX2阳性细胞密度约(4.63±0.62)百个/mm2。其中, 高浓度组SOX2阳性细胞密度比对照组减少约67.72%(P < 0.01), 说明米非司酮可以抑制干细胞增殖; ②Nestin阳性外胚层细胞分化: 荧光染色结果显示, EBs培养第11天时, 大量Nestin阳性细胞呈双极形态突起, 贯穿于NR管腔。对照组Nestin阳性细胞有效分化率约为(45.80±4.15)%, 低浓度组Nestin阳性细胞有效分化率约为(29.00±1.09)%, 高浓度组Nestin阳性细胞有效分化率约为(16.75±4.23)%(图 4A~C)。其中, 高浓度组比对照组减少约63.44%(P < 0.01)。此外, 在NR管腔内部发现了caspase-3阳性细胞, 且随着浓度增加而染色加深(图 4D~F), 提示米非司酮可以抑制神经系统发育, 导致神经管内部细胞凋亡; ③ CXCR4阳性中胚层细胞分化: 培养至第11天, CXCR4阳性细胞多集中在EBs的中心区域。随着用药浓度的增加, CXCR4阳性细胞相互缠绕成结。对照组CXCR4阳性细胞有效分化率约为(31.49±5.81)%, 低浓度组CXCR4阳性细胞有效分化率约为(41.81±5.40)%, 高浓度组CXCR4阳性细胞有效分化率约为(43.74±3.10)%(图 4G~I)。其中, 高浓度比对照组增加约28.01%(P < 0.05), 提示米非司酮可能促进心血管系统发育。而EBs内胚层FoxA2阳性细胞的表达较少, 且与米非司酮用药无明显影响(图 4J~L)。此外, 对神经细胞和神经胶质细胞的观察结果显示, 在外胚层中未发现NeuN阳性的成熟神经元细胞和GFAP阳性的神经胶质细胞。

|

Figure 4 Differentiation of germ layers after mifepristone exposure at D11.A-C: immunofluorescent labeling with Nestin (green) and DAPI staining (blue) were performed.Nestin positive cells (green) were radially distributed around neural rosettes.The number of Nestin positive cells remarkly decreased in experimental groups; D-F: Caspase-3 immunofluorescent labeling (red) and DAPI staining (blue) were carried out.Caspase-3 positive cells (red) were located in the inside of NR; G-I: SOX2 (green) and CXCR4 (red) immunofluorescence double labeling were operated.SOX2 positive cells (green) were mostly distributed in the periphery of EBs, and the number of SOX2 positive cells gradually decreased in the treatment group (P < 0.01).While CXCR4 positive cells (red) increased after mifepristone exposure; J-L: There were some FoxA2 positive cells (red) in EBs, but they had no obvious difference on the exposure of mifepristone.Scale bar, 10 μm (A-C) and 20 μm (D-L); M: The histogram and statistical analyses of differentiation of embryonic stem cells (SOX2 positive cell density); N: The histogram and statistical analyses of differentiation of ectoderm; O: The histogram and statistical analyses of mesoderm's differentiation; n=5, x ± s.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control group; △P < 0.05, △△P < 0.01 vs L-RU486 group |

综上, 米非司酮暴露影响胚层发育, 抑制胚胎干细胞增殖和外胚层细胞分化, 促进中胚层细胞增多。SOX2阳性细胞密度减少高达68%(P < 0.01, 图 4M), Nestin阳性细胞有效分化率减少达63%(P < 0.01, 图 4N), CXCR4阳性细胞有效分化率增加28%(P < 0.05, 图 4O), 可作为流产药物筛选的辅助指标。

讨论iPSCs可以作为流产药物的筛查模型。生殖毒性实验是指受试物在哺乳动物胚胎发育过程中对其生殖功能或发育成个体潜能的不利影响。研究表明: 美国医生案头参考(PDR)药物仅40%有生殖毒性方面的说明, 且其中60%为妊娠危害性不明的药物[15]。因此, 医药工作者非常有必要去筛选和判断药物是否具有生殖毒性, 以保证妊娠期妇女安全用药。iPSCs来源于人类体细胞, 可以模拟人体毒性试验, 且iPSCs不需要损伤胚胎组织, 避免了伦理学问题, 在药物生殖毒性试验中具有突出的优势[16]。Palmer等[17]利用人iPSCs研究类维生素A的发育毒性, Chaudhari等[18]通过人iPSC衍生的心肌细胞筛选化妆品中具有心脏毒性的化合物等, 说明iPSCs可以预测药物的生殖毒性, 但是iPSCs在流产药物筛选方面的研究相对较少。本实验利用iPSCs衍生的EBs作为药物流产毒性的筛查模型。首先, EBs在结构和功能上与胚胎早期发育阶段的胚泡相似[19], 适合筛选流产药物。其次, 此模型的实验操作简单, 观察指标易获得, 例如测量直径大小和细胞凋亡等, 在一般药物毒性实验室都可以进行操作。此外, 观察周期短, 一般10天左右就可完成药物检测。因此, 该药物筛查模型有较好的临床应用前景, 但仅限于3个月内早期妊娠的用药检测, 对于中晚期妊娠药物的检测, 需要对类皮质进行培养观察。

米非司酮是一种炔诺酮类衍生物, 具有拮抗孕激素、糖皮质激素和较弱的抗雄激素作用[20], 是目前临床上使用最广泛的流产药物。本研究根据米非司酮对EBs的直径大小、细胞凋亡和胚层发育这三方面的影响, 来制定药物流产不良反应的筛选标准。具体标准如下: ① EBs大小改变, 其直径缩小18%以上, 可以作为药物筛选的关键指标。EBs生长动力学可以预测化学物质的胚胎毒性[21], 通过EBs的直径大小变化来评估化学物质的生殖毒性。本研究发现米非司酮会导致EBs直径减少, 与Ghosh等[22-24]研究结果类似, 米非司酮用药后, 小鼠胚胎出现较大的卵裂球间隙, 细胞胞质内积聚着脂褐素、自噬体和多囊泡体等病理性改变[23, 24]。而米非司酮处理人ESCs源性EBs后, 其体积减少且未形成正常结构[25], 提示米非司酮影响EBs的发育; ②细胞凋亡变化, EBs内部细胞凋亡率增加大于44%, 可以作为药物筛选的重要指标。细胞凋亡在胚胎发育和清除多余细胞方面起关键作用。本研究发现米非司酮暴露导致细胞凋亡增加, EBs表面上皮细胞间和EBs内部出现空腔。Zhang等[25]研究发现米非司酮可调控Bax、Bcl-2及caspase-3等凋亡相关蛋白表达, 促进肿瘤细胞凋亡, 提示米非司酮促进EBs内部细胞凋亡, 且EBs内部空腔化的过程可能与米非司酮激活线粒体凋亡通路有关[26]; ③胚层分化情况, 米非司酮抑制胚胎干细胞增殖(抑制率高达68%), 抑制外胚层分化(抑制率达63%)和促进中胚层发育(增加率约28%), 它们可以作为药物筛选的参考指标。研究发现双酚A会导致EBs中多能性基因SOX2表达增加[27], 细胞增殖增多。而SOX2表达降低会上调分化调节因子Cdx2, 促进细胞分化[28], 提示米非司酮可能通过影响多能因子的表达而干扰EBs的分化。此外, Kim等[29]发现EBs表面存在孕激素受体, 外源性激素的改变会影响胚层的发育。在三胚层发育过程中, 米非司酮可能通过竞争性结合孕激素受体, 干预EBs外胚层中巢蛋白Nestin的表达, 引起神经玫瑰花状结节细胞大量凋亡, 阻碍神经系统的发育, 这与Gould等[30]研究结果一致。此外, 米非司酮可能通过上调心肌组织SDF-1 (干细胞归巢因子)表达, 导致CXCR4阳性干细胞迁移至损伤部位[31], 从而促进中胚层中心肌细胞增殖。也有研究发现孕激素可以影响心肌细胞内钙信号传导, 有助于心脏复极化过程, 抑制心肌细胞分化[32], 米非司酮也可能通过拮抗孕激素对中胚层发育产生影响。而FoxA2阳性的内胚层细胞表达量较少, 且与米非司酮用药关系不大, 故本研究以EBs胚胎干细胞SOX2阳性细胞密度、外胚层中Nestin有效分化率和中胚层中CXCR4有效分化率为药物流产毒性的参考指标。

综上所述, 本实验以iPSCs三维培养的EBs为模型, 研究流产药物米非司酮对EBs发育的影响。结果表明, 米非司酮可导致EBs直径变小、细胞凋亡率增加、抑制胚胎干细胞增殖、抑制外胚层细胞分化和促进部分中胚层细胞发育, 故以此标准建立药物流产毒性评价的指标, 利用已知推断未知药物的流产不良反应, 将为后续药物筛选提供参考。未来可利用此模型进行新药临床I期前的细胞实验, 初步评价新药对孕妇的致流产效应, 补充或者代替动物模型的药物测试数据。但是, 目前此模型还需要药物筛查验证。

作者贡献: 邓锦波负责课题设计、技术指导、文稿修改并提供资金支持; 毋姗姗完成绝大部分实验, 撰写了初稿并参与了论文修改; 范文娟、李瑞玲、王艳丽、李培全和李超杰提供实验技术指导。所有作者均对本文内容负责, 并认可作者排序。

利益冲突: 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Lacroix I, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy in France[J]. Lancet, 2000, 356: 1735-1736. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03209-8 |

| [2] |

Li DK, Liu L, Odouli R. Exposure to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs during pregnancy and risk of miscarriage: population based cohort study[J]. BMJ, 2003, 327: 368. DOI:10.1136/bmj.327.7411.368 |

| [3] |

Genschow E, Spielmann H, Scholz G, et al. Validation of the embryonic stem cell test in the international ECVAM validation study on three in vitro embryotoxicity tests[J]. Altern Lab Anim, 2004, 32: 209-244. |

| [4] |

Takeda Y, Harada Y, Yoshikawa T, et al. Chemical compoundbased direct reprogramming for future clinical applications[J]. Biosci Rep, 2018, 38: BSR20171650. DOI:10.1042/BSR20171650 |

| [5] |

Wada N, Wang B, Lin NH, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament fibroblasts[J]. J Periodontal Res, 2011, 46: 438-447. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01358.x |

| [6] |

Simara P, Tesarova L, Rehakova D, et al. Reprogramming of adult peripheral blood cells into human induced pluripotent stem cells as a safe and accessible source of endothelial cells[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2018, 27: 10-22. DOI:10.1089/scd.2017.0132 |

| [7] |

Qu X, Liu T, Song K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from human adipose-derived stem cells using a nonviral polycistronic plasmid in feeder-free conditions[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7: e48161. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0048161 |

| [8] |

Shi L, Cui Y, Zhou X, et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles of urinary induced pluripotent stem cells and human embryonic stem cells[C]//Proceedings of the 2017 7th Pan-Rim Bohai Sea Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Academic Exchange Conference(2017年第七届泛环渤海生物化学与分子生物学会学术交流会论文集). Shandong: Shandong Association of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2017: 114.

|

| [9] |

Lauschke K, Rosenmai AK, Meiser I, et al. A novel human pluripotent stem cell-based assay to predict developmental toxicity[J]. Arch Toxicol, 2020, 94: 3831-3846. DOI:10.1007/s00204-020-02856-6 |

| [10] |

Im A, Appleman LJ. Mifepristone: pharmacology and clinical impact in reproductive medicine, endocrinology and oncology[J]. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2010, 11: 481-488. DOI:10.1517/14656560903535880 |

| [11] |

Fan W, Wang Q, Deng J, et al. Mouse induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical organoids and its biological characteristics[J]. Acta Anat Sin(解剖学报), 2017, 48: 387-396. |

| [12] |

Fan W, Sun Y, Deng J, et al. Mouse induced pluripotent stem cells-derived Alzheimer's disease cerebral organoid culture and neural differentiation disorders[J]. Neurosci Lett, 2019, 711: 134433. DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134433 |

| [13] |

Lee JH, Park SY, Ahn C, et al. Second-phase validation study of an alternative developmental toxicity test using mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies[J]. J Physiol Pharmacol, 2020, 71: 223-233. |

| [14] |

Vasioukhin V, Bauer C, Yin M, et al. Directed actin polymerization is the driving force for epithelial cell-cell adhesion[J]. Cell, 2000, 100: 209-219. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81559-7 |

| [15] |

Sannersedt R, Lundborg P, Dnielsson BR, et al. Drugs during pregnancy: an issue of risk classification and information to prescribers[J]. Drug Saf, 1996, 14: 69-77. DOI:10.2165/00002018-199614020-00001 |

| [16] |

Aikawa N. A novel screening test to predict the developmental toxicity of drugs using human induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. J Toxicol Sci, 2020, 45: 187-199. DOI:10.2131/jts.45.187 |

| [17] |

Palmer JA, Smith AM, Egnash LA, et al. A human induced pluripotent stem cell-based in vitro assay predicts developmental toxicity through a retinoic acid receptor-mediated pathway for a series of related retinoid analogues[J]. Reprod Toxicol, 2017, 73: 350-361. DOI:10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.07.011 |

| [18] |

Chaudhari U, Nemade H, Sureshkumar P, et al. Functional cardiotoxicity assessment of cosmetic compounds using humaninduced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes[J]. Arch Toxicol, 2018, 92: 371-381. DOI:10.1007/s00204-017-2065-z |

| [19] |

Brickman JM, Serup P. Properties of embryoid bodies[J]. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, 2017, 6: e259. DOI:10.1002/wdev.259 |

| [20] |

Schaff EA. Mifepristone: ten years later[J]. Contraception, 2010, 81: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.004 |

| [21] |

Kang HY, Choi YK, Jo NR, et al. Advanced developmental toxicity test method based on embryoid body's area[J]. Reprod Toxicol, 2017, 72: 74-85. DOI:10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.06.185 |

| [22] |

Ghosh D, Sengupta J. Antinidatory effect of a single, early postovulatory administration of mifepristone(RU 486)in the rhesus monkey[J]. Hum Reprod, 1993, 8: 552-558. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138094 |

| [23] |

Juneja SC, Dodson MG. Effect of RU486 on different stages of mouse preimplantation embryos in vitro[J]. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 1990, 68: 1457-1460. DOI:10.1139/y90-220 |

| [24] |

Gallego MJ, Porayette P, Kaltcheva MM, et al. Opioid and progesterone signaling is obligatory for early human embryogenesis[J]. Stem Cells Dev, 2009, 18: 737-740. DOI:10.1089/scd.2008.0190 |

| [25] |

Zhang Y, Yi M. Mifepristone induces apoptosis and necrosis of human endometrial cells[J]. Curr Adv Obstet Gynecol(现代妇产科进展), 2016, 25: 931-933. |

| [26] |

Sun Y, Hou N, Lv Y, et al. Programmed cell death of embryoid body during the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. Chin J Biochem Mol Biol(中国生物化学与分子生物学报), 2004, 20: 838. |

| [27] |

Chen X, Xu B, Han X, et al. Effect of bisphenol A on pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells and differentiation capacity in mouse embryoid bodies[J]. Toxicol In Vitro, 2013, 27: 2249-2255. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2013.09.018 |

| [28] |

Bhattacharya S, Serror L, Nir E, et al. SOX2 regulates P63 and stem/progenitor cell state in the corneal epithelium[J]. Stem Cells, 2019, 37: 417-429. DOI:10.1002/stem.2959 |

| [29] |

Kim YY, Kim H, Suh CS, et al. Effects of natural progesterone and synthetic progestin on germ layer gene expression in a human embryoid body model[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21: 769. DOI:10.3390/ijms21030769 |

| [30] |

Gould E, Tanapat P, Rydel T, et al. Regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis in adulthood[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2000, 48: 715-720. DOI:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01021-0 |

| [31] |

Ryser MF, Ugarte F, Lehmann R, et al. S1P1 overexpression stimulates S1P-dependent chemotaxis of human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells but strongly inhibits SDF-1/CXCR4-dependent migration and in vivo homing[J]. Mol Immunol, 2008, 46: 166-171. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.016 |

| [32] |

Lee JH, Yoo YM, Jung EM, et al. Inhibitory effect of octylphenol and bisphenol A on calcium signaling in cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. J Physiol Pharmacol, 2019, 70: 435-442. |

2021, Vol. 56

2021, Vol. 56