结核病(tuberculosis, TB)是由结核分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mtb)引起的重大慢性传染病。WHO报告称2017年全球约1 000万结核病患者, 160万人死于结核病, 其中, 60%的患者来自印度(27%)、中国(9%)等7个国家[1]。多耐药性结核病(multi drug-resistant tuberculosis, MDR-TB)[2]、广泛耐药结核病(extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, XDR-TB)[3], 甚至完全耐药结核病(totally drug-resistant tuberculosis, TDR-TB)[4]的出现使得结核病的治疗与防控形势变得更加严峻。结核分枝杆菌是一种可以在多种宿主细胞内持留的致病菌[5], 可以抵抗或逃避宿主免疫攻击[6]和药物杀伤[7]。鞘氨醇-1-磷酸(sphingosine-1-phosphate, S1P)是一种重要的脂质介质, 能够降低Mtb诱导的细胞毒性[8], 促进被感染单核细胞的抗原加工和表达[9], 增强对Mtb杀伤的效果[10]。因此, 深入了解S1P及其受体在Mtb感染中的关键作用, 对于防控结核病及药物研发具有重要作用。

1 S1P概述S1P是鞘脂类代谢的产物, 能够调节各种类型细胞的存活、增殖、分化、迁移以及细胞骨架重排[11], 是调节细胞活动的关键信号分子。在细胞内, S1P作为调节增殖和存活的第二信使, 对Ca2+稳态的调控[12]和细胞凋亡的抑制发挥重要作用[13]。在细胞外, S1P通过与其特异性受体相结合, 激活下游通路并参与多种生理过程。同时, S1P信号通路在调节先天免疫系统的细胞活动时也具有重要作用[14]。

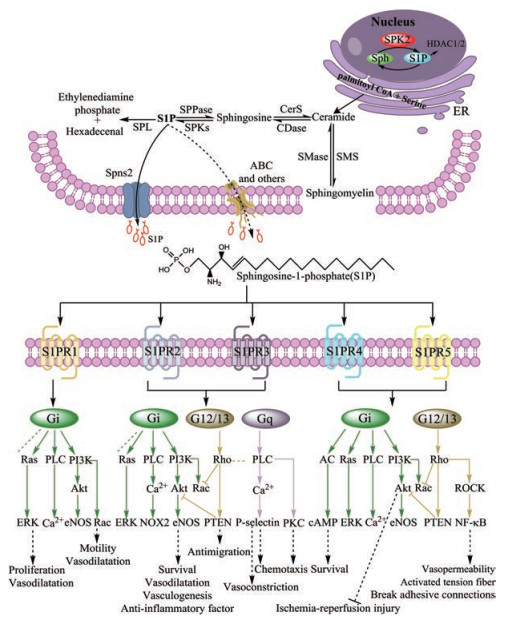

S1P含量主要受到其合成和降解相关的系列酶所控制。S1P是神经酰胺在神经酰胺酶作用下转化生成鞘氨醇, 并通过鞘氨醇激酶1和2 (SPK1和SPK2)催化而产生。神经酰胺不仅可以由鞘磷脂酶催化膜脂鞘磷脂而产生, 也可以通过多种应激源从内质网开始进行重新合成[15]。SPK磷酸化鞘氨醇产生S1P[16], S1P继而可以在胞内或胞外发挥一系列作用。S1P的降解主要由S1P裂解酶(SPL)和S1P磷酸酶(S1Pase)催化[17]进行, S1Pase能够通过水解磷酸盐催化S1P降解生成鞘氨醇, 两者间能够进行可逆转换。其次, S1P在转化生成鞘氨醇后由神经酰胺合成酶酰化成神经酰胺, 并且鞘氨醇和神经酰胺的相互转化在鞘脂类稳态中起着关键作用。细胞内感染期间SPL的分泌呈pH依赖性[17], 并能够不可逆地降解S1P生成磷酸乙醇胺和十六烯醛[18], 这一过程被认为是4种鞘脂质代谢通路的出口[19]。S1P跨膜分泌受到S1P转运蛋白调控[20], 除了Spns2 (spinster homolog 2)已被证明是S1P主要转运蛋白[21]外, ATP结合盒(ABC)转运蛋白也参与S1P的释放过程[21]。通常情况下, 当S1P被分泌到细胞外后, 通过结合周围细胞表面的S1P受体(S1PR)进行由内而外的信号传递[22]。

2 S1PR及其相关信号通路S1P能够进行自分泌/旁分泌, 并且通过结合主要的药物靶点——G蛋白偶联受体家族成员S1P受体(S1PRs)[23], 激活不同的信号通路, 调控细胞增殖、存活、分化和细胞骨架重排等多种细胞过程[11]。S1P-S1PR信号通路在癌症、自身免疫性疾病、炎症性疾病、神经系统疾病及心血管系统疾病中的作用已经得到了广泛的研究[24-27]。目前已经鉴定出的S1PR分别有S1PR1、S1PR2、S1PR3、S1PR4和S1PR5 (以前分别称为EDG-1、EDG-5、EDG-3、EDG-6和EDG-8)[14], 其在细胞中的时序性表达决定了S1P信号在各个器官的命运[23]。S1PR1~3在全身广泛表达, 而S1PR4主要在免疫系统中表达, S1PR5则主要在中枢神经系统和脾脏中表达[18]。这些受体在接受S1P信号后能够连接到不同的小G蛋白, 如Gi、Gq和G12/13[20], 随后这些小G蛋白可以激活下游信号分子, 从而引发一系列的应答反应。图 1所示为S1P代谢途径及其受体介导的信号通路图。

|

Figure 1 S1P metabolism and signaling pathways mediated by S1P receptors. ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; Sph: Sphingosine; CerS: Ceramide synthase; CDase: Ceramidase; SMS: Sphingomyelin; SMase: Sphingomyelinases; Ras: Ras family small GTPase; PLC: Phospholipase C; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositide 3 kinases; AC: Adenylate cyclase; Rho: Rho family of small GTPases; Akt: Protein kinase B; ROCK: Rho-associated kinase; ERK: Extracellular receptor kinase; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; Nox2: NADPH oxidase; PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog; PKC: Protein kinase C; Camp: Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

S1P-S1PR信号通路主要由其调节剂进行调控。FTY-720是S1PR的激动剂[17], 能够作用于除S1PR2以外的其他4种受体, 并可抑制淋巴细胞从淋巴结和其他次级淋巴组织中逸出[28]。FTY-720在肺癌、口腔癌、自身免疫性重症肌无力、系统性红斑狼疮等疾病治疗中所占据的作用和具备的潜能已经表明了鞘脂类药物的重要性[29-32], 但因其受体选择性低, 需要进一步研发新型调节剂。BAF312是在FTY-720基础上衍生而来的一种新型调节剂, 其受体选择性较FTY-720明显提高。BAF312对S1PR1和S1PR5的激动作用要远高于其他3种受体, 并能显著而持久地诱导S1PR1内化[33]; 另外, KRP-203作为FTY-720的另一新型衍生物, 其相对于BAF312和FTY-720具有更高的S1PR1选择性。与此同时, 随着S1P及S1P-S1PR通路重要性不断被发掘, 更多S1PR调节剂随即被发现并应用于机体调节中(如表 1[34-42]所示)。

| Table 1 S1P receptors and its regulator |

作为脂质信使, S1P发挥多种生理和病理功能。S1P调节单核细胞、T淋巴细胞和树突状细胞(DC)的存活、迁移、组织归巢和效应功能等[43]。树突状细胞作为抗原呈递细胞(APCs), 可触发T细胞免疫[44]。S1P及其信号通路在包括自身免疫性疾病、炎症、心血管疾病等多种类型疾病中发挥重要作用。

S1PR1在炎症反应中起关键作用, 并已被确定为多种疾病的治疗靶点[45]。炎症反应与包括癌症在内的多种疾病有着密切的关系[46], 靶向S1P-S1PR1轴可减轻癌症引起的骨痛和神经炎症, 同时其与慢性炎症也有直接联系[47, 48]。S1PR1还被证明可能是调节炎症性肠病B细胞功能的靶点[49]。S1PR1的表达可以促进多种疾病的发生, 如癌症、脑外伤、多发性硬化、阿尔茨海默病、肿瘤淋巴转移[50-54]等。其次, S1PR1通路在神经冲动的传递[55]和心脏保护[56]方面也具有重要作用。在血管保护方面, S1PR1信号通路维持内皮细胞屏障功能, 保护机体免受免疫复合物诱导的血管损伤[24]。同时, S1PR1信号还可以预防炎症引起的血管泄漏[57]以及减少急性肺损伤模型中的血管泄漏[58]。S1PR1调节细胞在血管和淋巴间的迁移, 显示其作为自身免疫性疾病治疗靶点的潜在作用[59]。

与S1PR1一样, S1PR2在血管功能中也起到关键的作用, 是维持血流动力学[60]的重要因子。S1PR2受体在正常血管形成和低氧诱导的小鼠病理性视网膜血管生成中发挥作用[61]。S1PR2驱动的炎症过程为病理性视网膜血管生成过程中的重要分子事件, 而S1PR2的拮抗可能是预防或治疗病理眼部新生血管形成的一种新的治疗手段。用S1PR2受体特异性拮抗剂JTE013阻断S1P诱导的螺旋动脉的血管收缩, 证明血管纹内的血管紊乱是导致S1PR2受体缺失小鼠耳聋的潜在机制[62]。此外, S1PR2也参与了糖尿病肾脏病内皮损伤的发病机制[63], 在逆转体内过敏性反应中尤为重要。S1PR2的存在对于人肥大细胞的激活以及小鼠过敏反应和肺水肿的诱导是必要的[64], 而特定的S1PR2激动剂可能有助于抵消与过敏性休克相关的血管扩张[65]。

S1PR3主要参与心脏成纤维细胞的重塑、增殖和分化。S1P和成纤维细胞生长因子可能通过激活S1PR3在脑发育、反应性胶质化、脑瘤形成等病理中发挥重要作用[66]。比较S1PR2和S1PR3受体敲除小鼠[67]发现S1PR2和S1PR3受体在介导缺血/再灌注损伤的心肌保护中发挥重要作用。同时, S1PR3参与了水肿、淋巴癌、血管免疫母细胞淋巴瘤、肿瘤、癌症等疾病的发生[68]。其次, S1P也能通过S1PR3受体诱导骨髓干细胞归巢从而介导肝硬化, 抑制S1P的形成或激活S1PR3受体可能治疗肝硬化[69]。

4 S1P在Mtb感染中的作用机制S1P不仅参与多种疾病, 如癌症、自身免疫性疾病、炎症性疾病、神经系统疾病及心血管系统疾病[24-27]等, 还可以通过抑制Mtb在胞内生长, 对结核病治疗起到重要的作用。当Mtb侵染巨噬细胞后, 巨噬细胞可以通过自噬对其进行有效清除[70]。伴随S1P的产生, SPK1可以刺激细胞自噬[71], 并且S1P还具有提高Mtb感染巨噬细胞的体外抗真菌活性以及结核患者支气管肺泡灌洗细胞的体外抗真菌和分枝杆菌活性的作用[72-74]。在结核分枝杆菌感染单核巨噬细胞的同时, 分别利用S1P和鞘氨醇处理单核巨噬细胞5天, 与仅感染结核分枝杆菌的对照组相比, S1P (5 μmol·L-1)能明显降低分枝杆菌的存活数, 但不同浓度的鞘氨醇(0.5、5和50 μmol·L-1)均不能降低分枝杆菌的存活数[72]。这说明S1P参与了抗Mtb感染。

肺是结核菌感染的重要器官, 并且也是S1P含量(29.11 ± 1.44 nmol·g-1)最高的器官之一[75]。肺结核患者S1P可显著性降低T细胞迁移以预防感染部位的炎症发生[76], 并能抑制淋巴细胞浸润[77]以减少结核模型中肺坏死[72]。结核患者气道黏膜表面和上皮内壁液中S1P浓度(47.5 ± 36.2 mmol·L-1)明显低于对照组(2 623 ± 1 576 mmol·L-1)[73], 这说明S1P对炎症性肺损伤可能起到一定的保护作用[59, 78]。其次, 当静脉注射S1P浓度为每鼠20 nmol时, 结核分枝杆菌感染小鼠的肺和脾中细菌数量最多可以减少47%, 肺组织损伤明显降低[72], 这可能与S1P选择性激活或重新编排(rearrangement)各种S1PR, 尤其是S1PR2有关[23]。同时, 这也表明S1P是宿主抗感染的一种新型调控因子并且参与调节肺部炎症反应。分析NCBI结核病患者与健康对照的转录组数据, 结核病患者S1PR3的转录水平提高, S1PR1和S1PR5的转录水平降低。这提示S1PR在结核病中发挥作用, 可能作为治疗结核病的靶标[79]。

S1P调节T细胞和Mtb感染过程中多种抗原递呈细胞。致病性分枝杆菌能够干扰宿主细胞MHC-Ⅱ类分子与抗原的结合, 及运送到细胞表面[20]。S1P能够促进MHC-Ⅱ递呈抗原给CD4+ T细胞, 保护Ⅱ型肺泡上皮细胞免受Mtb攻击[9]。S1P治疗的效果取决于施用时间。原发性感染期间, S1P治疗可显著减少肺肉芽肿内Mtb感染细胞的数量及肺和脾脏内的分枝杆菌数量[80]; 急性感染期间S1P治疗, 则会加重肺组织病理损伤并促使肺和脾脏的分枝杆菌增殖[80]。

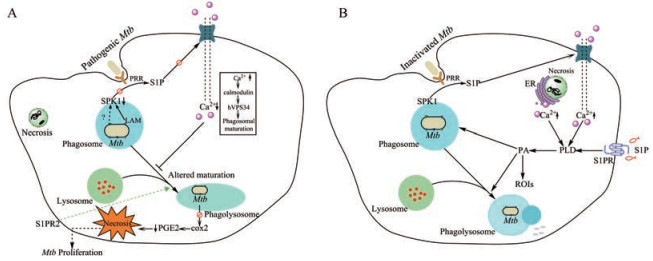

S1P是Mtb在宿主巨噬细胞中存活与否的关键决定因素[23]。S1P调控Ca2+的释放, 活化巨噬细胞磷脂酶D, 促进吞噬溶酶体成熟, 激活抗菌分子[8, 12, 81]。致病性分枝杆菌可以抑制SPK-1酶活性及其运输至吞噬体膜, 从而阻断巨噬细胞胞质Ca2+水平的升高, 阻止Ca2+依赖性吞噬体成熟, 提高Mtb在宿主巨噬细胞内的存活能力[81]。胞内结核分枝杆菌能够抑制环氧酶2 (COX2), 减少前列腺素2 (PGE2)的生成, 有利于Mtb将宿主细胞命运从凋亡转向坏死, 而坏死是Mtb存活和扩散所必需的[82]。结核分枝杆菌细胞壁的脂阿拉伯甘露聚糖(LAM)能够通过刺激宿主单核细胞中酪氨酸蛋白磷酸酶(SHP1)去磷酸化SPK1, 从而阻止吞噬体的成熟来逃避适应性免疫清除[82, 83], 但其他可能阻断S1P通路的机制目前尚不清楚。对于肺泡巨噬细胞中吞噬体成熟停滞的现象, 通过选择性上调肺泡巨噬细胞S1PR2相关抗菌信号或许能进行调节[23] (图 2A)。与致病性分枝杆菌相反的是, 灭活的Mtb无法抑制反而可以激活SPK并促进转移到吞噬体膜, 继而SPK通过磷酸化鞘氨醇产生S1P, 从主要的胞内Ca2+储存器—内质网(ER)[84]储存物中诱导Ca2+的增加[81]以此促进吞噬体的成熟。另外, 外源性S1P也能够通过诱导磷脂酶D活性促进胞内磷脂酸[85]的形成, 进而促进吞噬作用[86], 活性氧中间体的产生[87], ATP诱导分枝杆菌杀伤过程中吞噬溶酶体的成熟[88]等多种巨噬细胞抗菌活动(图 2B)。结核分枝杆菌感染过程中产生的神经酰胺/鞘脂类可通过促进缺氧[23]来建立分枝杆菌持留性[89], 这被认为有助于研究分枝杆菌耐药性。在这种情况下, 通过使用鞘脂类抑制剂联合利福平等结核病一线药物将有助于降低结核分枝杆菌的持留性和耐药性[90, 91]。

|

Figure 2 S1P mediates the mechanism of macrophage action during Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. A: Pathogenic Mtb inhibits the generation of S1P and promotes its survival in macrophages; B: The generation of S1P promotes the killing of Mtb in macrophages. PRR: Pattern recognition receptor; hVPS34: Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 34 homolog; COX2: Cycoloxygenase 2; PGE2: Prostaglandin E2; PLD: Phospholipase D; PA: Phosphatidic acid; ROIs: Reactive oxygen intermediates |

S1P是鞘脂类代谢的关键产物, 作用于细胞膜S1PR及作为胞内第二信使, 在多种生理和病理条件下均具有重要作用, 参与多种疾病的免疫调节过程。在Mtb感染过程中, S1P通过多种途径、多种方式有效抑制Mtb胞内生长。对于原发性Mtb感染治疗, S1P能够显著减少肺部分枝杆菌数量。外源性添加S1P也可以诱导胞内Ca2+增加, 提高磷脂酶D活性, 促进胞内磷脂酸的形成, 诱导吞噬酶体成熟, 促进吞噬作用等多种功能。对S1PR进行选择性激活或重排也能提高吞噬体杀伤Mtb的活性。对S1P及S1P-S1PR信号通路的研究将有助于揭示结核分枝杆菌逃避免疫的新机制, 探索鞘脂类调节剂与现有结核药物联合应用。S1P在结核病防控中的具体机制、涉及哪些关键基因, 仍需深入研究。

| [1] | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018[EB/OL]. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274453. |

| [2] | Tiberi S, du Plessis N, Walzl G, et al. Tuberculosis: progress and advances in development of new drugs, treatment regimens, and host-directed therapies[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2018, 18: e183–e198. |

| [3] | Dheda K, Gumbo T, Maartens G, et al. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, diagnosis, and management of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and incurable tuberculosis[J]. Lancet Respir Med, 2017, 5: 291–360. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30079-6 |

| [4] | Dwivedi VP, Bhattacharya D, Singh M, et al. Allicin enhances antimicrobial activity of macrophages during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection[J]. J Ethnopharmacol, 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2018.12.008 |

| [5] | Amaral EP, Lasunskaia EB, D'império-Lima MR. Innate immunity in tuberculosis: how the sensing of mycobacteria and tissue damage modulates macrophage death[J]. Microbes Infect, 2016, 18: 11–20. DOI:10.1016/j.micinf.2015.09.005 |

| [6] | da Costa AC, de Resende DP, Santos BPO, et al. Modulation of macrophage responses by CMX, a fusion protein composed of Ag85c, MPT51, and HspX from Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 623. |

| [7] | Agnihotri J, Singh S, Wais M, et al. Macrophage targeted cellular carriers for effective delivery of anti-tubercular drugs[J]. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov, 2017, 12: 162–183. |

| [8] | Emanuela G, Santucci MB, Michela S, et al. Natural lysophospholipids reduce Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced cytotoxi-city and induce anti-mycobacterial activity by a phagolysosome maturation-dependent mechanism in A549 type Ⅱ alveolar epithelial cells[J]. Immunology, 2010, 129: 125–132. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03145.x |

| [9] | Santucci MB, Greco E, Spirito MD, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes antigen processing and presentation to CD4+ T cells in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected monocytes[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2007, 361: 687–693. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.087 |

| [10] | Barnawi J, Tran H, Jersmann H, et al. Potential link between the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) system and defective alveolar macrophage phagocytic function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10: e0122771. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0122771 |

| [11] | Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018, 19: 175–191. DOI:10.1038/nrm.2017.107 |

| [12] | Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Lass H, Alemany R, et al. Sphingosine kinase-mediated Ca2+ signalling by G-protein-coupled receptors[J]. EMBO J, 1998, 17: 2830–2837. DOI:10.1093/emboj/17.10.2830 |

| [13] | Gonzalez L, Qian AS, Tahir U, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1, expressed in myeloid cells, slows diet-induced atherosclerosis and protects against macrophage apoptosis in Ldlr KO mice[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18: 2721. DOI:10.3390/ijms18122721 |

| [14] | Blaho VA, Hla T. An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors[J]. J Lipid Res, 2014, 55: 1596–1608. DOI:10.1194/jlr.R046300 |

| [15] | Brunkhorst R, Vutukuri R, Pfeilschifter W. Fingolimod for the treatment of neurological diseases - state of play and future perspectives[J]. Front Cell Neurosci, 2014, 8: 283. |

| [16] | Sinha P, Gupta A, Prakash P, et al. Differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from non-tubercular mycobacteria by nested multiplex PCR targeting IS6110, MTP40 and 32 kD alpha antigen encoding gene fragments[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2016, 16: 123. DOI:10.1186/s12879-016-1450-1 |

| [17] | Custódio R, McLean CJ, Scott AE, et al. Characterization of secreted sphingosine-1-phosphate lyases required for virulence and intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei[J]. Mol Microbiol, 2016, 102: 1004–1019. DOI:10.1111/mmi.13531 |

| [18] | Kleuser B. Divergent role of sphingosine 1-phosphate in liver health and disease[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19: 722. DOI:10.3390/ijms19030722 |

| [19] | Kumar A, Byun HS, Bittman R, et al. The sphingolipid degradation product trans-2-hexadecenal induces cytoskeletal reorganization and apoptosis in a JNK-dependent manner[J]. Cell Signal, 2011, 23: 1144–1152. DOI:10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.02.009 |

| [20] | Arish M, Husein A, Kashif M, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling: unraveling its role as a drug target against infectious diseases[J]. Drug Discov Today, 2016, 21: 133–142. DOI:10.1016/j.drudis.2015.09.013 |

| [21] | Nishi T, Kobayashi N, Hisano Y, et al. Molecular and physiological functions of sphingosine 1-phosphate transporters[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014, 1841: 759–765. DOI:10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.012 |

| [22] | Don-Doncow N, Zhang Y, Matuskova H, et al. The emerging alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and immune cells: from basic mechanisms to implications in hypertension[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2018. DOI:10.1111/bph.14381 |

| [23] | Sharma L, Prakash H. Sphingolipids are dual specific drug targets for the management of pulmonary infections: perspective[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 378. |

| [24] | Burg N, Swendeman S, Worgall S, et al. Sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor-1 signaling maintains endothelial cell barrier function and protects against immune complex-induced vascular injury[J]. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2018, 70: 1879–1889. DOI:10.1002/art.40558 |

| [25] | Cannavo A, Liccardo D, Komici K, et al. Sphingosine kinases and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors: signaling and actions in the cardiovascular system[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2017, 8: 556. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2017.00556 |

| [26] | Pyne NJ, McNaughton M, Boomkamp S, et al. Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors, sphingosine kinases and sphingosine in cancer and inflammation[J]. Adv Biol Regul, 2016, 60: 151–159. DOI:10.1016/j.jbior.2015.09.001 |

| [27] | Pyne S, Adams DR, Pyne NJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosine kinases in health and disease: recent advances[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2016, 62: 93–106. DOI:10.1016/j.plipres.2016.03.001 |

| [28] | Chiba K, Kataoka H, Seki N, et al. Fingolimod (FTY720), sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, shows superior efficacy as compared with interferon-β in mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2011, 11: 366–372. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2010.10.005 |

| [29] | Huang JK, Zhang T, Wang HM, et al. Treatment of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis rats with FTY720 and its effect on Th1/Th2 cells[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2018, 17: 7409–7414. |

| [30] | Li Y, Hu TH, Chen TJ, et al. Combination treatment of FTY720 and cisplatin exhibits enhanced antitumour effects on cisplatin-resistant non-small lung cancer cells[J]. Oncol Rep, 2018, 39: 565–572. |

| [31] | Shi DY, Tian TG, Yao S, et al. FTY720 attenuates behavioral deficits in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2018, 70: 293–304. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.009 |

| [32] | Velmurugan BK, Lee CH, Chiang SL, et al. PP2A deactivation is a common event in oral cancer and reactivation by FTY720 shows promising therapeutic potential[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2018, 233: 1300–1311. DOI:10.1002/jcp.26001 |

| [33] | Jeyanathan M, Yao YS, Afkhami S, et al. New tuberculosis vaccine strategies: taking aim at un-natural immunity[J]. Trends Immunol, 2018, 39: 419–433. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2018.01.006 |

| [34] | Bigaud M, Dincer Z, Bollbuck B, et al. Pathophysiological consequences of a break in S1P1-dependent homeostasis of vascular permeability revealed by S1P1 competitive antagonism[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11: e0168252. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0168252 |

| [35] | Bryan AM, Del Poeta M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors and innate immunity[J]. Cell Microbiol, 2018, 20: e12836. DOI:10.1111/cmi.12836 |

| [36] | Krause A, Brossard P, D'Ambrosio D, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator[J]. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn, 2014, 41: 261–278. DOI:10.1007/s10928-014-9362-4 |

| [37] | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Christopher R, Trokan L, et al. P369 safety and lymphocyte-lowering properties of etrasimod (APD334), an oral, potent, next-generation, selective S1P receptor modulator, after dose escalation in healthy volunteers[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2017, 11: S265–S266. |

| [38] | Sun N, Keep RF, Hua Y, et al. Critical role of the sphingolipid pathway in stroke: a review of current utility and potential therapeutic targets[J]. Transl Stroke Res, 2016, 7: 420–438. DOI:10.1007/s12975-016-0477-3 |

| [39] | Yamamoto R, Aoki T, Koseki H, et al. A sphingosine‐1‐phosphate receptor type 1 agonist, ASP4058, suppresses intracranial aneurysm through promoting endothelial integrity and blocking macrophage transmigration[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2017, 174: 2085–2101. DOI:10.1111/bph.13820 |

| [40] | Onuma T, Tanabe K, Kito Y, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) suppresses the collagen-induced activation of human platelets via S1P4 receptor[J]. Thromb Res, 2017, 156: 91–100. DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2017.06.001 |

| [41] | Kurata H, Kusumi K, Otsuki K, et al. Discovery of a 1-methyl-3, 4-dihydronaphthalene-based sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor agonist ceralifimod (ONO-4641). A S1P1 and S1P5 selective agonist for the treatment of autoimmune diseases[J]. J Med Chem, 2017, 60: 9508–9530. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00785 |

| [42] | Yamamoto R, Okada Y, Hirose J, et al. ASP4058, a novel agonist for sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors 1 and 5, ameliorates rodent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with a favorable safety profile[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e110819. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0110819 |

| [43] | Goetzl EJ, Rosen H. Regulation of immunity by lysosphingolipids and their G protein-coupled receptors[J]. J Clin Invest, 2004, 114: 1531–1537. DOI:10.1172/JCI200423704 |

| [44] | Tran TH, Tran TTP, Nguyen HT, et al. Nanoparticles for dendritic cell-based immunotherapy[J]. Int J Pharm, 2018, 542: 253–265. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.03.029 |

| [45] | Jin H, Han J, Resing D, et al. Synthesis and in vitro characterization of a P2×7 radioligand[123I]TZ6019 and its response to neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2017, 820: 8–17. |

| [46] | Jin K, Luo ZM, Zhang B, et al. Biomimetic nanoparticles for inflammation targeting[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2018, 8: 23–33. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.002 |

| [47] | Grenald SA, Doyle TM, Zhang H, et al. Targeting the S1P/S1PR1 axis mitigates cancer-induced bone pain and neuroinflammation[J]. Pain, 2017, 158: 1733–1742. DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000965 |

| [48] | Nagahashi M, Yamada A, Katsuta E, et al. Targeting the SphK1/S1P/S1PR1 axis that links obesity, chronic inflammation and breast cancer metastasis[J]. Cancer Res, 2018, 78: 1713–1725. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1423 |

| [49] | Suh JH, Saba JD. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated colon cancer: the fat's in the fire[J]. Transl Cancer Res, 2015, 4: 469–483. |

| [50] | Aytan N, Choi JK, Carreras I, et al. Fingolimod modulates multiple neuroinflammatory markers in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 24939. DOI:10.1038/srep24939 |

| [51] | Cuzzocrea S, Doyle T, Campolo M, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor subtype 1 as a therapeutic target for brain trauma[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2018, 35: 1452–1466. DOI:10.1089/neu.2017.5391 |

| [52] | Jin L, Liu WR, Tian MX, et al. The SphKs/S1P/S1PR1 axis in immunity and cancer: more ore to be mined[J]. World J Surg Oncol, 2016, 14: 131. DOI:10.1186/s12957-016-0884-7 |

| [53] | Liu H, Jin HJ, Yue XY, et al. PET imaging study of S1PR1 expression in a rat model of multiple sclerosis[J]. Mol Imaging Biol, 2016, 18: 724–732. DOI:10.1007/s11307-016-0944-y |

| [54] | Weichand B, Popp R, Dziumbla S, et al. S1PR1 on tumor-associated macrophages promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via NLRP3/IL-1β[J]. J Exp Med, 2017, 214: 2695–2713. DOI:10.1084/jem.20160392 |

| [55] | Meng H, Lee VM. Differential expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors 1-5 in the developing nervous system[J]. Dev Dyn, 2009, 238: 487–500. DOI:10.1002/dvdy.21852 |

| [56] | Chen YZ, Wang F, Wang HJ, et al. Sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor-1 (S1PR1) signaling protects cardiac function by inhibiting cardiomyocyte autophagy[J]. J Geriatr Cardiol, 2018, 15: 334–345. |

| [57] | Wang LC, Dudek SM. Regulation of vascular permeability by sphingosine 1-phosphate[J]. Microvasc Res, 2009, 77: 39–45. DOI:10.1016/j.mvr.2008.09.005 |

| [58] | McVerry BJ, Peng XQ, Hassoun PM, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate reduces vascular leak in murine and canine models of acute lung injury[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004, 170: 987–993. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200405-684OC |

| [59] | Mi JQ, Zhao MM, Yang S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of H002, a novel S1PR1 modulator, and its metabolites in rat blood using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2016, 6: 576–583. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.06.001 |

| [60] | Lorenz JN, Arend LJ, Robitz R, et al. Vascular dysfunction in S1P2 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor knockout mice[J]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2007, 292: R440–R446. DOI:10.1152/ajpregu.00085.2006 |

| [61] | Skoura A, Sanchez T, Claffey K, et al. Essential role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 in pathological angiogenesis of the mouse retina[J]. J Clin Invest, 2007, 117: 2506–2516. DOI:10.1172/JCI31123 |

| [62] | Kono M, Belyantseva IA, Skoura A, et al. Deafness and stria vascularis defects in S1P2 receptor-null mice[J]. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282: 10690–10696. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M700370200 |

| [63] | Imasawa T, Kitamura HR, Ohkawa R, et al. Unbalanced expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in diabetic nephropathy[J]. Exp Toxicol Pathol, 2010, 62: 53–60. DOI:10.1016/j.etp.2009.02.068 |

| [64] | Oskeritzian CA, Price MM, Hait NC, et al. Essential roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 in human mast cell activation, anaphylaxis, and pulmonary edema[J]. J Exp Med, 2010, 207: 465–474. DOI:10.1084/jem.20091513 |

| [65] | Olivera A, Eisner C, Kitamura Y, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 are vital to recovery from anaphylactic shock in mice[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120: 1429–1440. DOI:10.1172/JCI40659 |

| [66] | Bassi R, Anelli V, Giussani P, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate is released by cerebellar astrocytes in response to bFGF and induces astrocyte proliferation through Gi-protein-coupled receptors[J]. Glia, 2006, 53: 621–630. DOI:10.1002/glia.20324 |

| [67] | Means CK, Brown JH. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signalling in the heart[J]. Cardiovasc Res, 2009, 82: 193–200. |

| [68] | Li QF, Wu CT, Guo Q, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces Mcl-1 upregulation and protects multiple myeloma cells against apoptosis[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2008, 371: 159–162. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.037 |

| [69] | Li CY, Kong YX, Wang H, et al. Homing of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells mediated by sphingosine 1-phosphate contributes to liver fibrosis[J]. J Hepatol, 2009, 50: 1174–1183. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.028 |

| [70] | Lam A, Prabhu R, Gross CM, et al. Role of apoptosis and autophagy in tuberculosis[J]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2017, 313: L218–L229. DOI:10.1152/ajplung.00162.2017 |

| [71] | Moruno-Manchon JF, Uzor NE, Ambati CR, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1-associated autophagy differs between neurons and astrocytes[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9: 521. DOI:10.1038/s41419-018-0599-5 |

| [72] | Garg SK, Volpe E, Palmieri G, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces antimicrobial activity both in vitro and in vivo[J]. J Infect Dis, 2004, 189: 2129–2138. DOI:10.1086/386286 |

| [73] | Garg SK, Santucci MB, Panitti M, et al. Does sphingosine 1-phosphate play a protective role in the course of pulmonary tuberculosis?[J]. Clin Immunol, 2006, 121: 260–264. DOI:10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.002 |

| [74] | Garg SK, Valente E, Greco E, et al. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances antimycobacterial activity both in vitro and ex vivo[J]. Clin Immunol, 2006, 121: 23–28. DOI:10.1016/j.clim.2006.06.003 |

| [75] | Murata N, Sato K, Kon J, et al. Quantitative measurement of sphingosine 1-phosphate by radioreceptor-binding assay[J]. Anal Biochem, 2000, 282: 115–120. DOI:10.1006/abio.2000.4580 |

| [76] | Guyot-Revol V, Innes JA, Hackforth S, et al. Regulatory T cells are expanded in blood and disease sites in patients with tuberculosis[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2006, 173: 803–810. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200508-1294OC |

| [77] | Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists[J]. Science, 2002, 296: 346–349. DOI:10.1126/science.1070238 |

| [78] | Peng XQ, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, et al. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004, 169: 1245–1251. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200309-1258OC |

| [79] | Berry MPR, Graham CM, McNab FW, et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis[J]. Nature, 2010, 466: 973–977. DOI:10.1038/nature09247 |

| [80] | Sali M, Delogu G, Greco E, et al. Exploiting immunotherapy in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice: sphingosine 1-phosphate treatment results in a protective or detrimental effect depending on the stage of infection[J]. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol, 2009, 22: 175–181. DOI:10.1177/039463200902200120 |

| [81] | Malik ZA, Thompson CR, Hashimi S, et al. Cutting edge: Mycobacterium tuberculosis blocks Ca2+ signaling and phagosome maturation in human macrophages via specific inhibition of sphingosine kinase[J]. J Immunol, 2003, 170: 2811–2815. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2811 |

| [82] | Chandrasekaran P, Saravanan N, Bethunaickan R, et al. Malnutrition: modulator of immune responses in tuberculosis[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1316. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01316 |

| [83] | Teng O, Ang CKE, Guan XL. Macrophage - bacteria interactions - a lipid-centric relationship[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1836. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01836 |

| [84] | Cui CC, Merritt R, Fu LW, et al. Targeting calcium signaling in cancer therapy[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2017, 7: 3–17. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.11.001 |

| [85] | Desai NN, Zhang H, Olivera A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a metabolite of sphingosine, increases phosphatidic acid levels by phospholipase D activation[J]. J Biol Chem, 1992, 267: 23122–23128. |

| [86] | Poerio N, Bugli F, Taus F, et al. Liposomes loaded with bioactive lipids enhance antibacterial innate immunity irrespective of drug resistance[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 45120. DOI:10.1038/srep45120 |

| [87] | Girón-Calle J, Forman HJ. Phospholipase D and priming of the respiratory burst by H2O2 in NR8383 alveolar macrophages[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2000, 23: 748–754. DOI:10.1165/ajrcmb.23.6.4227 |

| [88] | Fairbairn IP, Stober CB, Kumararatne DS, et al. ATP-mediated killing of intracellular mycobacteria by macrophages is a P2X7-dependent process inducing bacterial death by phagosome-lysosome fusion[J]. J Immunol, 2001, 167: 3300–3307. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3300 |

| [89] | Speer A, Sun J, Danilchanka O, et al. Surface hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by the outer membrane protein Rv0888 supports replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages[J]. Mol Microbiol, 2015, 97: 881–897. DOI:10.1111/mmi.13073 |

| [90] | Ishitsuka A, Fujine E, Mizutani Y, et al. FTY720 and cisplatin synergistically induce the death of cisplatin-resistant melanoma cells through the downregulation of the PI3K pathway and the decrease in epidermal growth factor receptor expression[J]. Int J Mol Med, 2014, 34: 1169–1174. DOI:10.3892/ijmm.2014.1882 |

| [91] | Maeurer C, Holland S, Pierre S, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induced mTOR-activation is mediated by the E3-ubiquitin ligase PAM[J]. Cell Signal, 2009, 21: 293–300. DOI:10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.10.016 |

2019, Vol. 54

2019, Vol. 54