Predictive performance and analysis of a vancomycin population pharmacokinetic model in Chinese pediatric patients

1. Department of Pharmacy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning 530021, China;

2. Department of Pediatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning 530021, China

万古霉素自问世50多年来, 一直是治疗耐药革兰阳性菌感染的主流药物[1]。万古霉素的疗效和不良反应已被证实与万古霉素血清浓度有关[2, 3]。优化万古霉素给药剂量以快速实现充分的药物暴露是治疗的必要条件。一些证据表明, 目前儿科推荐的基于体重(每天40~60 mg·kg-1)的万古霉素给药方案可能导致万古霉素血清浓度低于治疗水平[4, 5]。因此, 有必要对万古霉素的浓度进行有效预测, 以尽快达到合适的浓度。群体药代动力学(PPK)模型和贝叶斯分析法可以较准确地制定个体化给药方案, 快速达到有效治疗浓度, 减少药物不良反应[6, 7]。目前已有多个儿童万古霉素PPK模型报道, 但大多数针对高加索儿童[8-10]。为数不多的中国儿童万古霉素PPK模型也都是针对婴幼儿[11-13]。本研究旨在评估我院前期建立的0~10岁儿童万古霉素PPK模型[14]的预测性能, 以期为万古霉素儿童个体化给药提供参考。

材料与方法 病例选择 回顾性收集2013年8月至2017年5月在广西医科大学第一附属医院住院静脉应用万古霉素的儿童患者作为研究对象。该研究方案经广西医科大学第一附属医院伦理委员会批准, 患者或其家属均知情同意。纳入标准:静脉应用万古霉素≥3天; 年龄≤10岁; 至少有1次万古霉素稳态浓度值。排除标准:弥漫性血管内凝血(disseminated intravascular coagulation, DIC)或囊性纤维化; 用药期间进行连续肾脏替代治疗或血液透析; 用药前7天内接受万古霉素治疗≥3天。

数据收集 收集患者的人口学资料和临床资料, 包括出生后周龄(postnatal age, PNA)、性别、体重(WT)、临床诊断、万古霉素给药方案、给药时间和血药浓度、采血时间、用药前和用药期间血清肌酐(Scr)、万古霉素血药浓度值等。前期建立的儿童万古霉素群体药代动力学模型[14]如下:

|

$

\begin{array}{l}

{\rm{CL}}\left( {{\rm{L\cdot}}{{\rm{h}}^{ - 1}}} \right){\rm{ }} = 11.75 \times [{\rm{PN}}{{\rm{A}}^{0.4672}} \times ({\rm{PN}}{{\rm{A}}^{0.4672}} + \\

\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;{33.3^{0.4672}}{)^{ - 1}}] \times {\left( {{\rm{WT}}/70} \right)^{0.75}} \times {{\rm{e}}^{0.362}}

\end{array}

$

|

|

$

\mathit{V}\left( {\rm{L}} \right) = 54.49 \times {\rm{WT}}/70 \times {{\rm{e}}^{0.6711}}

$

|

统计分析 应用SPSS 20进行统计学分析, 将患者根据年龄和特殊体重进行分组。根据前期建立的万古霉素PPK模型, 使用NONMEM软件中的贝叶斯分析模块, 求出患者个体浓度预测值, 与实测值比较。用平均预测误差(mean error, ME)和平均相对预测误差(ME%)评估模型的准确度; 用平均绝对误差(mean absolute error, MAE), 均方根误差(root mean squared error, RMSE)和相对预测误差在±30%以内分布的比例评估模型的精密度。如果ME趋近于0, MAE值< 2.5 mg·L-1, RMSE < 4 mg·L-1, 则预测性能良好, 具体计算公式如下。并使用拟合优度(goodness-of-fit)、直观预测检验法(VPC)对模型的预测性能进行验证, Bland-Altman一致性评价方法评价预测值与观察值的一致性。

|

$

{\rm{ME}} = 1/\mathit{n}\sum {_{i = 1}^n\left( {预测值 - 观察值} \right)}

$

|

|

$

{\rm{MAE}} = 1/\mathit{n}\sum {_{i = 1}^n\left| {预测值 - 观察值} \right|}

$

|

|

$

\begin{array}{l}

{\rm{ME\% }} = 1/\mathit{n}\sum {_{i = 1}^n\left[ {\left( {预测值 - } \right.} \right.} \\

\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\left. {\left. {观察值} \right)/观察值} \right] \times 100\%

\end{array}

$

|

|

$

{\rm{RMSE}} = {\left[ {1/\mathit{n}{{\sum {_{i = 1}^n\left( {预测值 - 观察值}\;\;\;\;\;\;\ \right)} }^2}} \right]^{1/2}}

$

|

|

$

相对标准误差 = \left[ {\left( {预测值 - 观察值} \right)/观察值} \right] \times 100\%

$

|

结果 1 一般资料 共纳入191例儿童患者, 371个血药浓度值。人口学资料和临床资料(建模组数据和外部验证数据)见表 1。

表1(Table 1)

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients

| Characteristics |

Model development cohort |

External validation cohort |

| Number of patient |

54 |

191 |

| Samples |

128 |

371 |

| Sex (female: male)

|

31:23 |

77:114 |

| Age, ≤28day (0-4weeks]

|

8 (14.81%)

|

34 (17.80%)

|

| Weight < 1 500 g |

1 (12.50%)

|

7 (20.59%)

|

| Weight ≥1 500 g |

7 (87.50%)

|

27 (79.41%)

|

| Age, 28 day-1 year (4-52 weeks]

|

16 (29.63%)

|

48 (25.13%)

|

| Age, 1 year-3 year (52-156 weeks]

|

13 (24.08%)

|

33 (17.28%)

|

| Age, 3 year-10 year (156-573 week]

|

17 (31.48%)

|

76 (39.79%)

|

| Postnatal age, weeks (mean, range)

|

124.30 (1.29, 521.40)

|

157.90 (0.29, 568.00)

|

| Weight / kg (mean, range)

|

10.36 (1.40, 33.50)

|

11.60 (0.83, 50.00)

|

| Serum creatinine / mg·dL-1 (mean, range)

|

0.39 (0.15, 1.32)

|

2.97 (0.68, 13.46)

|

| Vancomycin serum concentrations / mg·L-1 (mean, range)

|

12.21 (0.15, 40.39)

|

9.31 (0.30, 45.60)

|

|

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients

|

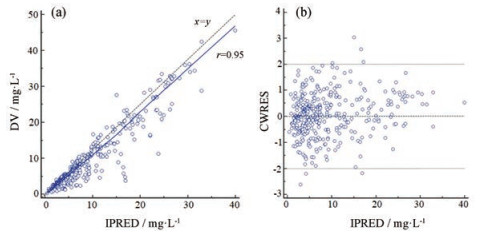

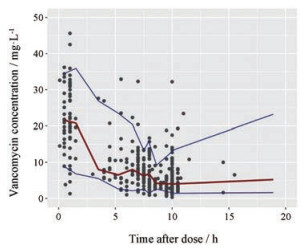

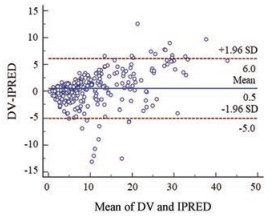

2 模型的预测性能 万古霉素血清浓度的ME、ME%、MAE和RMSE见表 2; 浓度相对预测误差在±30%以内的比例为82.75%。拟合优度见图 1; VPC图见图 2; 个体预测值与实测值的Bland-Altman一致性评价情况见图 3; 不同分组的一致性评价情况见图 4。由图 1可知, 模型的个体预测值与实测值的相关性较好, 模型条件权重残差(CWRES)与个体预测值(IPRED)图示最终模型CWRES值主要分布于±2之间, 均匀分布于坐标轴上下两侧, 不随浓度、时间显著变化, 表明模型拟合效果理想, 个体预测浓度能较准确地反映实测浓度。图 2中红线为预测值中位数线, 蓝线为预测值95%置信区间分界线, 大部分浓度点在置信区间之内, 但仍有部分点在置信区间外, 说明模型在群体预测方面存在部分偏差。图 3和图 4显示模型个体预测值与实测值的一致性较好, 不同分组中除了体重低于1 500 g的极低体重儿组的95%置信区间较大, 其他分组均显示较好的一致性。

表2(Table 2)

Table 2 The mean error (ME), mean relative error (ME%), mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) values of vancomycin serum concentrations (95% CI). *Not applicable because of a negative value

| Item |

ME / mg·L-1

|

ME %

|

MAE / mg·L-1

|

RMSE / mg·L-1

|

| All concentrations |

-0.50 (-0.79, -0.21)

|

6.03% (1.18%, 10.88%)

|

1.84 (1.62, 2.07)

|

2.86 (2.46, 3.21)

|

| Age, < 28 day (0-4 weeks]

|

-0.56 (-1.30, 0.18)

|

10.09% (-2.69%, 24.52%)

|

2.18 (1.65, 2.72)

|

3.08 (2.13, 3.81)

|

| WT < 1 500 g |

-0.15 (-3.28, 3.59)

|

29.36% (-29.61%, 88.33%)

|

3.57 (1.24, 5.91)

|

4.88 (NA*, 7.21)

|

| WT ≥1 500 g |

-0.69 (-1.36, -0.02)

|

7.35% (-5.44%, 20.14%)

|

1.92 (1.45, 2.39)

|

2.60 (1.89, 3.15)

|

| Age, 28 day-1 year (4-52 weeks]

|

-0.79 (-1.35, -0.23)

|

1.53% (-5.78%, 8.84%)

|

1.91 (1.49, 2.34)

|

2.77 (2.17, 3.27)

|

| Age, 1-3 year (52-156 weeks]

|

-0.36 (-1.05, 0.32)

|

1.73% (-10.18%, 13.65%)

|

1.49 (0.91, 2.08)

|

2.75 (1.15, 3.72)

|

| Age, 3-10 year (156-573 weeks]

|

-0.36 (-0.82, 0.09)

|

8.32% (0.30%, 16.35%)

|

1.80 (1.44, 2.16)

|

2.85 (2.12, 3.43)

|

|

Table 2 The mean error (ME), mean relative error (ME%), mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) values of vancomycin serum concentrations (95% CI). *Not applicable because of a negative value

|

讨论 群体药代动力学模型的外部验证是检验模型的最严格的方法[15]。万古霉素成人模型[16, 17]和婴儿模型[18, 19]的外部验证都已有发表。鉴于多数儿童模型均针对婴幼儿, 并且考虑不同年龄段儿童万古霉素代谢可能存在不同, 将使用万古霉素的儿童根据年龄分成4组来分析:年龄≤28天(0~4周], 28天~1岁(4~52周], 1~3岁(52~156周], 3~10岁(156~573周]。根据表 2结果显示, 结果均在可接受的范围。ME%值偏差较大, 结合图 1拟合优度诊断图, 考虑这与儿童万古霉素血药浓度值普偏较低(< 5 mg·L-1)有关。

本模型与其他大多数模型[12, 18]之间的差异是缺乏肾功能协变量。静脉注射万古霉素主要通过肾小球滤过消除, 75%由尿液排出[20], 肾功能被认为是影响万古霉素排泄的重要指标。在建模阶段, 本模型尝试将肾功能相关指标作为协变量纳入, 考察结果为WT、PNA和内生肌酐清除率(creatinine clearance, CLcr)之间有相关性, WT、PNA与血清肌酐(serum creatinine, Scr)无相关性。在模型的开发过程中, 在向前添加步骤中, Scr没有保留在全模型中, 而在向后消除步骤中, CLcr被排除, 因此最终模型不包括肾功能协变量。但本模型仍然具有较高的预测性能, 这可能是由于儿童体重和/或年龄与肾功能之间的高度相关性[21-23]。因此, 本模型通过儿童患者体重和/或年龄可以直接用于预测浓度和设计初始给药方案

万古霉素在极低出生体重(≤1 500 g)新生儿中的药代动力学表现出很大差异[24]。在本研究中, 模型在≤28天年龄组的预测性能略差于其他3个年龄组。考虑到模拟偏差是否是由于极低出生体重的新生儿造成, 将年龄≤28天的患者根据体重分为:体重 < 1 500 g和≥1 500 g亚组。根据表 2和图 4显示, 重量 < 1 500 g组MAE > 2.5 mg·L-1, RMSE > 4 mg·L-1, 95%置信区间较大, 预测性能明显差于 > 1 500 g组。从统计因素考虑, 可能由于极低体重儿样本量较小, 存在较大抽样误差; 从生理因素考虑, 极低出生体重儿通常细胞外液比例高, 表观分布容积较大, 这导致血药浓度低。此外, 新生儿是一个快速生长发育的特殊人群, 其组织和器官(如肝脏和肾脏)尚未成熟, 各种酶系统的发展并不完善, 药物的吸收、分布、代谢、排泄和其他体内过程、毒理反应在个体之间差异很大, 很难预测[25]。Kato等[24]研究发现Scr和输液量是对极低出生体重儿万古霉素药代动力学参数有显著影响的协变量。因此, 在没有肾功能指标的情况下, 很难通过年龄和体重来预测极低出生体重儿体内万古霉素的药代动力学, 本模型不适用于极低出生体重儿。

本模型可基本满足0~10岁儿童万古霉素初始治疗方案制定和药物暴露程度预测的应用, 并内置于复旦大学附属华山医院研制的万古霉素个体化给药决策辅助系统“SmartDose”[26], 以期进行多中心、扩大样本量的外部验证。同时寻找更适合作为万古霉素肾清除标志物的协变量, 以完善儿童万古霉素模型。

2019, Vol. 54

2019, Vol. 54