2. 中国医学科学院基础医学研究所&北京协和医学院基础学院药理学系, 北京 100005

2. Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and School of Basic Medicine, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100005, China

STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, STAT3)是信号转导与转录激活因子STAT蛋白家族的重要成员。STAT家族具有信号转导和转录活化双重功能, 当细胞因子或生长因子激活相应受体后, STAT蛋白被激活后, 将胞外信号转入细胞核内, 从而调控相关基因的转录与表达。迄今为止, 在哺乳动物细胞中已有7个STAT家族成员被报道, 分别为STAT1、STAT2、STAT3、STAT4、STAT5A、STAT5B和STAT6, 其中, STAT3广泛存在于各类细胞和组织中[1], 能够被多种细胞因子激活。在正常生理状态下, STAT3的活化快速而短暂, 但在多种肿瘤细胞中, STAT3则被持续性激活并呈高水平表达[2, 3], 研究已证实STAT3与肿瘤的形成与发展密切相关。

1 STAT3与肿瘤 1.1 STAT3的结构1994年, STAT3作为白细胞介素-6 (IL-6)炎症反应过程中的急性期反应因子(acute-phase response factor, APRF)被纯化出来。研究表明, STAT3的表达在心脏、肝脏、大脑、胸腺及睾丸中水平较高[4]。STAT3蛋白由750~795个氨基酸组成, 相对分子质量约为92 kDa, 其在细胞中存在4种异构体, 包括长型的STAT3α、截短型的STAT3β和STAT3γ、以及STAT3δ[5, 6]。该蛋白主要包含6个结构域(图 1): N末端结构域、卷曲-螺旋结构域、DNA结合域、连接结构域、SH2结构域(Src homology 2 domain)、C末端转录活化结构域。此外, STAT3还有2个重要的磷酸化位点:酪氨酸磷酸化位点(Y705)和丝氨酸磷酸化位点(S727)。其中, N末端结构域、DNA结合域、SH2结构域的作用最为重要, 靶向这三个结构域中的任意一个均能达到直接抑制STAT3的效果[7-10]。

|

Figure 1 The ribbon diagram of the STAT3 homodimer-DNA complex (PDB ID: 4E68) and domain structure of STAT3 with the individual domains indicated [dark blue = N-terminal (1-130), light blue = 4-helix bundle (131-320), light yellow = DNA binding (321-465), light orange = connector (465-585), orange = SH2 (586-722), red = C-terminal (723-770)] |

STAT3蛋白能够被受体和非受体酪氨酸激酶磷酸化而激活[11-14] (图 2)。在经典的JAK-STAT3信号通路中, 细胞因子、生长因子等多肽类配体与细胞膜上相应的受体结合, 导致后者形成二聚体, 进而招募并激活细胞质中的JAK激酶(Janus kinase, JAKs)蛋白[15]。研究表明这些因子包括: ①细胞因子(如IL-6、干扰素-α等)[16]; ②生长因子[如血小板源性生长因子、表皮生长因子(epidermal growth factor, EGF)等]; ③ G蛋白(如促甲状腺素类、巨噬细胞炎症蛋白质等)[17]。活化后的JAK将膜上受体磷酸化, STAT3蛋白通过SH2结构域与该受体磷酸化的酪氨酸残基结合, 并在JAK的作用下磷酸化Y705残基, 从而实现活化并形成二聚体[18, 19]。二聚化的STAT3与受体分离后, 进入细胞核, 结合到靶基因的DNA应答元件上, 调节靶基因的转录和表达。此外, 非受体酪氨酸激酶如v-Abl、c/v-Src[20, 21]也可以激活STAT3蛋白, 实现STAT3的磷酸化和二聚化, 使其转入细胞核内发挥信号转导与转录调控的作用。

|

Figure 2 STAT3 signaling and its activation signals. Cytokines or growth factors binding to their corresponding cell surface receptors activates the Tyr kinases activities of the receptors, JAKs or Src. STAT3 is recruited to the activated receptor for phosphorylation by Tyr kinases on critical Tyr residue, leading to STAT3:STAT3 dimerization and activation. Nonreceptor Tyr kinases Src and AbL also activate STAT3. Activated STAT3 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where it binds DNA and coactivators and induces gene transcription |

在正常细胞中, STAT3的激活迅速而短暂。核蛋白酪氨酸磷酸酶如TC-PTP和TC45等能够使已经磷酸化的STAT3去磷酸化, 从而使细胞核内的STAT3蛋白返回到细胞质中[22, 23]。然而, 在肿瘤组织中, 癌细胞和周围的一些炎症细胞可产生并释放各种可溶性因子到肿瘤微环境中, 使STAT3持续活化, 从而促进肿瘤的发生和发展。

STAT3作为一种在肿瘤细胞的生长、增殖、血管生成和侵袭中重要的参与者, 其表达失调与多种肿瘤的发展相关。研究发现, 在多种人类实体肿瘤以及血液瘤细胞中均呈现出STAT3的异常高表达和持续性激活, 如卵巢癌[24]、胰腺癌[25]、前列腺癌[26]、头颈癌[27]、乳腺癌[28]、白血病[29]及非小细胞肺癌(non- small cell lung carcinoma, NSCLC)[30]等。STAT3作为转录因子, 其过度激活可上调多种靶基因的转录和表达, 包括抗凋亡蛋白Bcl-xL和Bcl-2、增殖相关蛋白Cyclin Dl和c-Myc、促血管发生因子VEGF, 以及侵袭和转移相关蛋白MMP-2和MMP-9等[16, 31]。此外, 最新的研究提示, STAT3不仅在肿瘤细胞中调节致癌基因的表达, 还可以通过免疫抑制来促进人类癌症的发生[32]。在免疫细胞中, STAT3的激活能抑制免疫介质并促进免疫抑制因子的产生。因此, STAT3调节宿主免疫也是促使肿瘤细胞产生的诱因。

2 STAT3抑制剂与肿瘤治疗近年来, 以STAT3为靶点的抑制剂研究成为抗肿瘤药物研发的热点。目前抑制STAT3信号通路有间接和直接两种策略:间接策略系阻断STAT3信号通路的上游分子, 间接抑制STAT3的信号转导功能, 如抑制JAK、Src、Abl、Lyn等[33-39]。其中, 靶向JAK2激酶的抑制剂一直是科学家们的研究热点, 且其进入临床开发的时间要先于STAT3抑制剂。然而大部分抑制剂虽然进入临床, 却并未成功上市, 这是由于这些激酶抑制剂主要作用在酶催化中心, 与其他激酶的结构类似, 易导致脱靶, 故不良反应较大, 不易成药。

与之相比, 直接靶向STAT3蛋白的抑制剂更为理想。直接抑制STAT3靶点的作用机制主要包括3个策略, 即抑制STAT3单体的磷酸化、抑制STAT3- STAT3二聚体的形成以及抑制进入细胞核内的STAT3与DNA结合。按照作用位点主要可分为作用在SH2结构域、DNA结合域、N末端结构域以及C末端转录活化结构域的STAT3抑制剂。本文以此分类综述STAT3抑制剂的抗肿瘤活性及研究进展。

2.1 作用于SH2结构域的STAT3抑制剂目前, 大部分STAT3抑制剂都是靶向作用于STAT3蛋白的SH2结构域。SH2结构域是STAT3发挥其生物学功能的重要结构域。该结构域包含着与另一个STAT3蛋白结合的口袋, 在STAT3蛋白Y705位点磷酸化后, 能使两个活化的STAT3单体结合形成二聚体, 移入细胞核, 结合DNA开启特定靶基因[8], 该区域一旦被抑制会导致STAT3功能的丧失。

研究表明, STAT3蛋白的SH2结构域中有3个比较理想的抑制位点[40]。第1个位点是STAT3蛋白pY705的结合口袋, 主要由极性残基(如R609)组成, 它们可以通过氢键和静电相互作用与配体相结合。第2个位点是pY+1, 由T620、K626、Q635和S636组成的疏水性口袋。第3个位点是pY-1, 由M586、G587、F588、I589和S590组成的疏水性口袋。其中pY-1是STAT3蛋白所特有的。大部分靶向SH2结构域开发的STAT3抑制剂至少要与上述三个位点中的两个结合。

2.1.1 肽类及拟肽类STAT3抑制剂肽类及拟肽类STAT3抑制剂的主要作用位点为SH2结构域, 系以STAT3蛋白或糖蛋白130 (glycoprotein 130, gp130)上的磷酸化酪氨酸残基及其邻近的氨基酸残基序列为模板设计合成的磷酸肽。该类抑制剂能阻碍两个STAT3单体的结合或者STAT3与细胞因子或生长因子受体的结合, 从而阻止蛋白的二聚化及核转移, 阻断STAT3与DNA的结合。

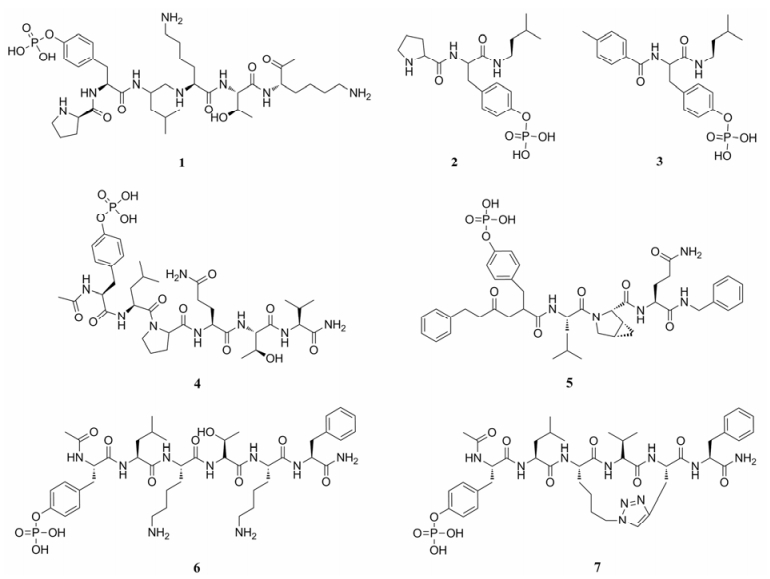

2001年, Jove课题组[41]设计合成了一个由6个氨基酸残基构成并且能与STAT3蛋白的SH2结构域结合的磷酸肽PpYLKTK (1, P:脯氨酸, L:亮氨酸, K:赖氨酸, T:苏氨酸, 图 3)。该肽能够抑制STAT3的DNA结合活性(IC50为235 μmol·L-1)。体外实验发现, 该磷酸肽可以与STAT3单体形成复合物。由此表明, 磷酸肽1一旦结合在SH2结构域, 能与STAT3单体竞争性占据SH2结构域上的结合口袋, 从而阻断蛋白的二聚化。进一步研究发现, 磷酸化的酪氨酸残基以及与其相邻的“Y+1”位亮氨酸残基和“Y-1”位的任意氨基酸残基组成的三肽部分(XpYL, X:任意氨基酸残基)是此类肽分子具有STAT3抑制活性必须的结构单元, 由此设计了三肽抑制剂PpYL (2), 其抑制STAT3二聚化的活性IC50为182 μmol·L-1。在此基础上, 研究者们对化合物2进行一系列修饰改造, 发现用4-氰基苯基替换脯氨酸残基的化合物ISS610 (3)活性明显提升(IC50 = 42 ± 23 μmol·L-1), 其可抑制STAT3的DNA结合活性, 并能抑制v-src转染的小鼠成纤维细胞、人乳腺癌及肺癌细胞中STAT3的持续性激活[42]。

|

Figure 3 Chemical structures of peptides and peptidomimetics STAT3 inhibitors |

在STAT3信号转导过程中, 活化的细胞因子和生长因子受体(如IL-6R、EGFR以及gp130)与STAT3蛋白上的SH2结构域结合后可激活STAT3蛋白。研究发现, 这些受体蛋白上均含有相同的YXXQ (Q:谷氨酰胺)序列, 这段磷酸肽能够抑制STAT3与上述受体的结合, 从而阻断其活化。Ren等[43]从gp130的磷酸化蛋白中发现了另一个多肽类STAT3抑制剂pYLPQTV (4, V:缬氨酸)。凝胶迁移(electrophoretic mobility shift assay, EMSA)实验表明, 其抑制STAT3: DNA结合活性的IC50为0.15 μmol·L-1。Dourlat等[44]对4进行了构效关系研究, 发现“pY”至“pY+3”位的氨基酸残基均能与STAT3形成氢键, 且“pY+2”位的脯氨酸残基对化合物具有构象限制作用, 有利于其与STAT3蛋白的结合。随后, 该研究小组对化合物4进行了大量的结构改造得到化合物5, 对STAT3亲和力最强, 其抑制STAT3与DNA结合的IC50为68 nmol·L-1。

此外, Chen等[45]还直接以STAT3蛋白pY705及其相邻的氨基酸残基序列为模板设计了一种短肽, 即乙酰基-pYLKTKF (6, F:苯丙氨酸), 发现其与STAT3的SH2结构域的亲和力较强, 对STAT3的抑制常数Ki为25.9 μmol·L-1, 同时可有效地抑制STATs蛋白家族的活性。对化合物6的C端、N端及“pY+ 1”“pY+2”位进行结构改造, 发现将“pY+2”位替换为cis-3, 4-亚甲基脯氨酸时可产生构象限制, 从而增强化合物对受体的亲和力[42, 44, 46, 47]。在6的基础上, 研究人员经缩合、叠氮化、成环和脱保护基等一系列步骤合成了具有构象限制的大环拟肽类化合物(7), 该化合物与STAT3蛋白的亲和力(Ki = 7.3 μmol·L-1)较化合物6明显提高。

由此可见, 肽类及拟肽类STAT3抑制剂主要通过模拟STAT3蛋白或gp130上的磷酸化酪氨酸残基及其邻近的氨基酸残基序列, 其共同特点是这类磷酸肽具有磷酸化的酪氨酸残基以及与其相邻的“Y+1”位亮氨酸残基和“Y-1”位的任意氨基酸残基组成的肽单位。

2.1.2 作用于SH2结构域的STAT3小分子抑制剂肽类及拟肽类化合物虽然有较高的生物学活性, 但是在体内易代谢失活, 且存在生物利用度低、成药性较差等问题。近年来, 随着计算机模拟和筛选技术的发展, 研究人员通过计算机虚拟筛选、高通量筛选等技术, 发现了许多靶向SH2的小分子抑制剂。

化合物STA-21 (8, 图 4)是通过虚拟筛选发现的第一个STAT3小分子抑制剂, 其抑制荧光素酶活性的浓度为20 μmol·L-1[48]。研究发现, 其能与STAT3的SH2结构域结合, 并抑制STAT3自身的二聚化以及与DNA的结合, 从而阻断STAT3的信号转导通路。对化合物8进行结构优化, 得到化合物LLL-3 (9)和LLL- 12 (10), 与8相比, 它们的细胞渗透性均有明显改善。其中, 化合物10可显著抑制STAT3与DNA的结合, 对横纹肌肉瘤细胞系的IC50为1.74 μmol·L-1[49, 50]。

|

Figure 4 Chemical structures of small molecule STAT3 inhibitors by targeting SH2 domain |

Schust等[51]通过高通量筛选的方法, 发现了另一个作用于STAT3蛋白SH2结构域的小分子抑制剂Stattic (11)。荧光偏振实验表明, 11对STAT3蛋白结合的IC50值为5.1 μmol·L-1, 可选择性抑制STAT3的活化、二聚化及核转移, 诱导STAT3依赖性乳腺癌细胞系的凋亡。随后, Zhang等[52]发现化合物11能抑制STAT3活化并下调HIF-1α和VEGF的表达, 并且在体内外实验均证实其可增加食管鳞状细胞癌(esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ESCC)细胞对放疗的敏感度, 是潜在的ESCC放疗增敏药物。

2013年, Kim等[53]发现OPB-31121可干扰JAK2/ STAT3通路, 下调JAK2和gp130, 并抑制JAK2和STAT3的磷酸化; OPB-31121可抑制胃癌细胞增殖, 诱导其凋亡, 抑制抗凋亡蛋白的表达。Brambilla等[54]利用对接和分子动力学模拟, 并通过分子水平结合实验(Kd = 10 nmol·L-1)对STAT3 SH2结构域的关键氨基酸残基进行定点突变, 证明OPB-31121作用于SH2结构域。与其他SH2抑制剂作用机制不同, OPB-31121可同时抑制STAT3蛋白上Y705和S727的磷酸化。目前, 该化合物正在进行实体瘤治疗的Ⅰ期临床研究[55]。

4-羰基-2, 6-二亚苄基环己酮衍生物也是一类JAK-STAT3信号通路抑制剂[56], 该类化合物能有效地抑制STAT3表达及磷酸化。体外实验表明, 化合物13r (12)对MDA-MB-231人乳腺癌细胞、A549肺癌细胞及DU145前列腺癌细胞系表现出较强的抗增殖活性(IC50值分别为0.64、1.88、1.63 μmol·L-1), 对正常细胞则表现出相对低的细胞毒性。表面等离子共振结合实验证实化合物12与STAT3的直接相互作用(Kd = 7.93 μmol·L-1); 分子对接结果表明, 12可同时占据SH2结构域中的3个亚位点(Y705位点、L706位点以及侧面的口袋)。这类化合物的作用靶点仍有待进一步研究。

除了以上列举的STAT3抑制剂, 研究人员通过虚拟筛选、高通量筛选等技术还发现了许多作用于SH2结构域的小分子抑制剂。其中, 磺胺类化合物, 如LLL12, 在人脐带血管内皮细胞中显著抑制了STAT3的磷酸化, 且对骨肉瘤细胞呈现出抗肿瘤活性[57]; 喹啉酮类化合物, 如S3I-201 (13)[58], 抑制STAT3- STAT3二聚体的形成以及STAT3与DNA的结合与转录活性, 从而下调一系列STAT3调控基因的表达。此外, 13能够优先抑制STAT3持续激活的肿瘤细胞的生长并诱导凋亡。进一步的体内实验表明, 其能抑制人乳腺肿瘤的生长; Oncrasin类化合物, 如NSC- 743380 (14)[59], 能够抑制JAK2/STAT3磷酸化并抑制下游因子细胞周期蛋白Cyclin D1的表达, 对来源于人肺癌、结肠癌、卵巢癌、肾癌和乳腺癌的细胞系均具有高度抑制活性(GI50≤10 nmol·L-1); 咔唑类化合物, 如化合物15[60]以及姜黄素类化合物, 如FLLL11 (16), 均能够抑制IL-6诱导的STAT3磷酸化和核移位[61, 62]。

此外, 近年来研究者们已从天然产物中获得了多种具有STAT3抑制活性的活性单体。倍半萜内酯类化合物, 如Santamarine (STM, 17)[63]以及菲啶型生物碱类化合物, 如氯化两面针碱(18)[64]能够通过降低STAT3 705位酪氨酸的磷酸化来抑制STAT3的活化。三萜类化合物2-氰基-3, 12-二氧代齐墩果烷-1, 9-二烯- 28-酸(CDDO, 19)及其甲酯CDDO-Me (20)已进入临床阶段, 用于血癌和实体瘤的治疗[65, 66]。研究显示, 20能通过抑制STAT3信号的转导而抑制乳腺癌细胞的生长, 还可通过抑制IL-6的表达和STAT3的磷酸化作用杀死多重耐药的卵巢癌细胞[67, 68]。

由此可见, STAT3小分子抑制剂主要通过虚拟筛选、高通量筛选等多种手段发现, 结构种类比较丰富, 其结构特点主要是以刚性多环结构为母体, 同时环上连接极性基团, 可以形成氢键。另外, 在化合物16、17、19、20中还有不饱和键, 可以通过加成产生更加牢固的共价键。

综上所述, 自第一个靶向SH2结构域的抑制剂报道, 距今已有17年的历史[41]。期间, 科学家们开发了大量的SH2抑制剂, 但大多数抑制剂仍处于临床前研究阶段, 且目前没有上市的药物。其主要原因有以下三点: ①靶向SH2结构域的STAT3抑制剂主要通过干扰STAT3蛋白Y705的磷酸化及STAT3二聚化发挥作用, 然而STAT3-STAT3二聚化是一种蛋白-蛋白相互作用, 由于相互作用面积较大, 用小分子阻断其相互作用, 具有较大困难; ②目前已开发的小分子抑制剂的活性普遍在微摩级别, 在复杂的人体环境中需要较高的剂量才能达到抑制STAT3的效果, 这无疑增加了因药物脱靶效应而对正常组织产生毒性的可能; ③ SH2结构域在多种酪氨酸蛋白中高度保守, 且其位点正电荷残基富集, 对小分子所携带的负电荷要求较高, 因此针对SH2位点设计的抑制剂普遍存在可成药性低、不良反应大等缺点。

研究者们最初认为二聚化是STAT3执行功能的必备步骤, 故一直将目光集中在SH2结构域。最新文献报道, STAT3的单体和没有被磷酸化的STAT3也可以与其他蛋白相互作用, 调控下游的靶基因的转录, 发挥其相应的生物学功能[69-72]。因而, 靶向SH2结构域可能不足以完全抑制肿瘤细胞内异常的STAT3信号, 作用于SH2结构域的STAT3抑制剂有待更多临床前与临床研究的验证。

2.2 作用于DNA结合域的典型STAT3抑制剂DNA结合结构域(DNA binding domain, DBD)位于高度保守的第321~465位氨基酸之间, 是STAT3蛋白与DNA结合的重要区域, 具有一定的特异性。该结构域能够使STAT3与DNA上的启动子反应元件相结合从而来诱导靶基因的表达。其中, STAT3能够识别的DNA序列为TTCC(G=C)GGAA[73]。

2012年, Buettner等[74]在筛选SH2抑制剂时发现了化合物C48 (21, 图 5), 然而机制研究中发现, 它并不能与STAT3的SH2结构域结合。点突变等多种生物化学技术发现21能够使STAT3半胱氨酸(C468)上的谷胱甘肽巯基烷基化。进一步研究发现, 21能够阻碍肿瘤细胞核中已活化的STAT3蛋白的积累, 阻止STAT3的过表达, 显著地抑制了小鼠的肿瘤生长。与其他STATs相比, C468是STAT3 DBD区所特有的氨基酸残基, 修饰该位点可选择性地阻碍STAT3二聚体与DNA结合。然而, 21除了能对C468进行烷基化, 其对细胞里的其他巯基同样有烷基化的作用, 因此特异性较差。

|

Figure 5 Chemical structures of small molecule inhibitors of STAT3 by binding to DBD |

在同一时期, Huang等[72]以DBD为口袋进行虚拟筛选设计, 发现了小分子抑制剂inS3-54 (22, IC50为13.8 μmol·L-1), 这是第一次针对DBD进行STAT3抑制剂筛选的尝试。EMSA实验表明, 22可以选择性抑制STAT3与DNA的结合, 但并不影响STAT3的活化和二聚化。此外, 化合物22可以有效地抑制肿瘤细胞的增殖、迁移和侵袭。对化合物22进行结构优化, 发现了活性更高、特异性更好的小分子inS3-54A18 (23, IC50为4 μmol·L-1)[75], 23与DBD结合后可有效抑制STAT3下游靶基因的表达。体内实验表明, 23可以显著地抑制肺转移瘤的生长和转移。该化合物为后续的靶向DBD的STAT3小分子抑制剂的研究奠定了基础, 证明了靶向STAT3 DBD获得活性分子的可行性。

最新研究发现, (E)-2-甲氧基-4-[3-(4-甲氧基苯基)丙-1-烯-1-基]苯酚(MMPP, 24)是靶向DNA结合域的STAT3抑制剂, 具有潜在的抗肿瘤活性。(E)-2, 4-双(对羟基苯基)-2-丁烯醛(BHPB)是一种酪氨酸——果糖美拉德反应产物, 通过抑制STAT3的活化发挥其有效的抗炎和抗关节炎的作用。Son等[76]对其改造时发现衍生物24, 在A549及NCI-H460细胞系中均表现出一定的抗肿瘤活性(IC50值分别为12.80、11.99 μg·mL-1)。氨基酸残基定点突变实验表明, 24直接与DBD上T456的羟基结合, 从而调控与细胞周期和凋亡有关的基因, 诱导G1期细胞周期停滞和凋亡。此外, 体内外实验均发现24能有效抑制STAT3的磷酸化及其与DNA结合的活性。化合物24能否作为靶向STAT3的DBD的抗癌药物仍在研究中。

综上可以发现, 作用于DBD的STAT3抑制剂主要特点是具有高反应活性的结构, 例如容易进行烷基化的半胱氨酸中的巯基、环氧结构、易发生Michael加成的乙烯基砜、α, β-不饱和酮以及酰胺结构等。目前为止, 对于靶向STAT3: DNA结合界面的小分子药物设计仍没有引起研究者们足够的重视。虽然已经有一些靶向DBD的小分子抑制剂被开发出来, 但针对这一靶点尚没有统一筛选模型及活性评价方式。从已有化合物的活性来看, 该靶点的小分子抑制剂值得继续关注, 但是其最终药效仍需要临床的检验。

2.3 作用于N末端结构域的STAT3抑制剂STAT3蛋白的N端结构域包含约130个氨基酸, 由8个螺旋组成[10, 77]。N末端结构域主要负责介导STAT3二聚体结合到DNA位点以及细胞响应所依赖的蛋白质—蛋白质相互作用, 其中包括使邻近的两个STAT3二聚体蛋白的结合更紧密, 从而促进了STAT3蛋白的四聚化。

2007年, Timofeeva等[77]首次从STAT3蛋白的N-末端结构域的螺旋衍生出一类短肽, 其能特异性地识别并结合STAT3, 从而在不影响STAT3磷酸化状态的前提下抑制其转录活性。将这类短肽与一种透膜蛋白(Penetratin:RQIKIWFPNRR-Nle-KWKK-NH2)融合产生的透膜形式(Ac-EIKFLEQVDKFY-penetratin)可以选择性地抑制人MDA-MB-231、MDA-MB-435和MCF-7乳腺癌细胞的生长, 并诱导凋亡(IC50 < 10 μmol·L-1)。在此基础上, 研究人员合成了一种高选择性的STAT3 N末端结构域抑制剂ST3-Hel2A-2, 该化合物能够高效激活促凋亡基因CHOP的表达从而诱导肿瘤细胞的凋亡。这类短肽的发现为STAT3抑制剂作为新的抗癌治疗方式提供了一种新策略[78]。

2.4 作用于C末端转录活化结构域的STAT3抑制剂C末端结构域也被称作转录活化区(transcription activating domain, TAD), 与基因的转录激活有关。STAT3通过该区域与其他转录活化因子和调节因子, 如p300/CBP、c-Jun和组蛋白乙酰化转移酶(HATs)等的相互作用发挥对靶基因的转录与激活[79]。在不同的STATs亚型中, 该结构域的差异较大, 故抑制C末端结构域可能会达到较高的选择性。

最近, Huang等[80]基于蛋白结构的精准变构药物筛选设计方法, 成功发现了STAT3的变构位点及变构抑制剂。研究人员发现除了STAT3蛋白的SH2结构域, 在其C端结构域区域也存在着可以抑制STAT3二聚化进而调控DNA转录的位点(D171、N175、Q202和M213), 并在此位点上精准筛选到变构活性小分子K116 (25, 图 6)。25对STAT3的IC50达到7.99 μmol·L-1。

|

Figure 6 Chemical structure of small molecule inhibitor of STAT3 by binding to C-terminal domain |

STAT3在多种肿瘤细胞中异常活化与表达, 且其水平与肿瘤分化程度、浸润转移及预后密切相关。随着对STAT3通路的不断研究, STAT3可作为肿瘤治疗的一个重要的药物靶点这一观点已经得到了科学家的证实, 将STAT3抑制剂作为治疗肿瘤的研究具有很大的发展潜力。当然, 目前针对STAT3抑制剂抗肿瘤的研究主要还停留在体外活性初筛的水平, 在动物体内进行的药理和毒理研究较少, 进入临床研究阶段的化合物更是寥寥无几(表 1、2)。STAT3抑制剂作为一类潜在的新型抗肿瘤药, 其从科学研究到临床应用之间还有一定的距离。尽管针对SH2结构域的抑制剂已被广泛报道, 但普遍存在活性低、选择性差等问题。针对DBD、N末端结构域和C末端结构域抑制剂已经有了一定的突破, 并表现出一定的优势, 这些研究都为STAT3抑制剂的设计提供了新的思路。对于STAT3抑制剂开发来说, 对DBD、N末端结构域和C末端结构域的探索具有较大的研究空间, 药物化学工作者应该关注上述3个结构域的小分子抑制剂的研发。虽然目前还没有STAT3抑制剂上市, 但相信随着研究的深入, 药物设计方法的不断优化以及靶向STAT3其他结构域的小分子抑制剂的不断研究, 可以更高效地发现STAT3小分子抑制剂, 为肿瘤的治疗提供新的解决办法和思路。

| Table 1 Known STAT3 inhibitors identified to date, their modes of action, cellular effects and tumor models tested. DBD: DNA binding domain; ND: N-terminal domain; CD: C-terminal domain; n/d: Not determined |

| Table 2 Inhibitors that have therapeutic effects on STAT3 in animal experiments. DBD: DNA binding domain; ND: N-terminal domain; CD: C-terminal domain; n/d: Not determined; ig: Intragastric administration; ip: Intraperitoneal injection; iv: Intravenous injection |

| [1] | Takeda K, Noguchi K, Shi W, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1997, 94: 3801–3804. DOI:10.1073/pnas.94.8.3801 |

| [2] | Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE Jr. Stat3 and Stat4:members of the family of signal transducers and activators of transcription[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994, 91: 4806–4810. DOI:10.1073/pnas.91.11.4806 |

| [3] | Xiong A, Yang Z, Shen Y, et al. Transcription factor STAT3 as a novel molecular target for cancer prevention[J]. Cancers, 2014, 6: 926–957. DOI:10.3390/cancers6020926 |

| [4] | Paukku K, Silvennoinen O. STATS as critical mediators of signal transduction and transcription:lessons learned from STAT5[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2004, 15: 435–455. DOI:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.09.001 |

| [5] | Hevehan DL, Miller WM, Papoutsakis ET. Differential expression and phosphorylation of distinct STAT3 proteins during granulocytic differentiation[J]. Blood, 2002, 99: 1627–1637. DOI:10.1182/blood.V99.5.1627 |

| [6] | Benekli M, Baer MR, Baumann H, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins in leukemias[J]. Blood, 2003, 101: 2940–2954. DOI:10.1182/blood-2002-04-1204 |

| [7] | Dumoutier L, de Meester C, Tavernier J, et al. New activation modus of STAT3:a tyrosine-less region of the interleukin-22 receptor recruits STAT3 by interacting with its coiled-coil domain[J]. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284: 26377–26384. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M109.007955 |

| [8] | Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE Jr. Maximal activation of transcription by STAT1 and STAT3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation[J]. Cell, 1995, 82: 241–250. DOI:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9 |

| [9] | Ren Z, Mao X, Mertens C, et al. Crystal structure of unphosphorylated STAT3 core fragment[C]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2008, 374: 1-5. |

| [10] | Becker S, Groner B, Muller CW. Three-dimensional structure of the Stat3beta homodimer bound to DNA[J]. Nature, 1998, 394: 145–151. DOI:10.1038/28101 |

| [11] | Carlesso N, Frank DA, Griffin JD. Tyrosyl phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins in hematopoietic cell lines transformed by Bcr/Abl[J]. J Exp Med, 1996, 183: 811–820. DOI:10.1084/jem.183.3.811 |

| [12] | Ilaria RL Jr, Van Etten RA. P210 and P190(BCR/ABL) induce the tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of multiple specific STAT family members[J]. J Biol Chem, 1996, 271: 31704–31710. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.49.31704 |

| [13] | Frank DA, Varticovski L. BCR/abl leads to the constitutive activation of STAT proteins, and shares an epitope with tyrosine phosphorylated Stats[J]. Leukemia, 1996, 10: 1724–1730. |

| [14] | Nieborowska-Skorska M, Wasik MA, Slupianek A, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)5 activation by BCR/ABL is dependent on intact Src homology (SH)3 and SH2 domains of BCR/ABL and is required for leukemogenesis[J]. J Exp Med, 1999, 189: 1229–1242. DOI:10.1084/jem.189.8.1229 |

| [15] | Ihle JN. The Janus protein tyrosine kinases in hematopoietic cytokine signaling[J]. Semin Immunol, 1995, 7: 247–254. DOI:10.1006/smim.1995.0029 |

| [16] | Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATS in cancer inflammation and immunity:a leading role for STAT3[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2009, 9: 798–809. DOI:10.1038/nrc2734 |

| [17] | Wang Y, Ning H, Ren F, et al. Gdx/UBL4A specifically stabilizes the TC45/STAT3 association and promotes dephosphorylation of STAT3 to repress tumorigenesis[J]. Mol Cell, 2014, 53: 752–765. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.020 |

| [18] | Darnell JE Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins[J]. Science, 1994, 264: 1415–1421. DOI:10.1126/science.8197455 |

| [19] | Schindler C, Darnell JE Jr. Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands:the JAK-STAT pathway[J]. Annu Rev Biochem, 1995, 64: 621–651. DOI:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003201 |

| [20] | Danial NN, Pernis A, Rothman PB. Jak-STAT signaling induced by the v-abl oncogene[J]. Science, 1995, 269: 1875–1877. DOI:10.1126/science.7569929 |

| [21] | Jove R, Kornbluth S, Hanafusa H. Enzymatically inactive p60c-src mutant with altered ATP-binding site is fully phosphorylated in its carboxy-terminal regulatory region[J]. Cell, 1987, 50: 937–943. DOI:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90520-4 |

| [22] | Ren F, Geng Y, Minami T, et al. Nuclear termination of STAT3 signaling through SIPAR (STAT3-interacting protein as a repressor)-dependent recruitment of T cell tyrosine phosphatase TC-PTP[J]. FEBS Lett, 2015, 589: 1890–1896. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.031 |

| [23] | Yamamoto T, Sekine Y, Kashima K, et al. The nuclear isoform of protein-tyrosine phosphatase TC-PTP regulates interleukin-6-mediated signaling pathway through STAT3 dephosphorylation[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2002, 297: 811–817. DOI:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02291-X |

| [24] | Huang M, Page C, Reynolds RK, et al. Constitutive activation of STAT3 oncogene product in human ovarian carcinoma cells[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2000, 79: 67–73. DOI:10.1006/gyno.2000.5931 |

| [25] | Sun Y, Yang S, Sun N, et al. Differential expression of STAT1 and p21 proteins predicts pancreatic cancer progression and prognosis[J]. Pancreas, 2014, 43: 619–623. DOI:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000074 |

| [26] | Liao Z, Nevalainen MT. Targeting transcription factor STAT5a/b as a therapeutic strategy for prostate cancer[J]. Am J Transl Res, 2011, 3: 133–138. |

| [27] | Cohen-Kaplan V, Jrbashyan J, Yanir Y, et al. Heparanase induces signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) protein phosphorylation:preclinical and clinical significance in head and neck cancer[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287: 6668–6678. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.271346 |

| [28] | Barash I. STAT5 in breast cancer:potential oncogenic activity coincides with positive prognosis for the disease[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2012, 33: 2320–2325. DOI:10.1093/carcin/bgs362 |

| [29] | Sanchez-Ceja SG, Reyes-Maldonado E, Vazquez-Manriquez ME, et al. Differential expression of STAT5 and Bcl-xL, and high expression of Neu and STAT3 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma[J]. Lung Cancer, 2006, 54: 163–168. DOI:10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.07.012 |

| [30] | Casetti L, Martin-Lanneree S, Najjar I, et al. Differential contributions of STAT5A and STATB to stress protection and tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance of chronic myeloid leukemia stem/progenitor cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2013, 73: 2052–2058. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3955 |

| [31] | Germain D, Frank DA. Targeting the cytoplasmic and nuclear functions of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 for cancer therapy[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2007, 3: 5665–5669. |

| [32] | Wang Y, Shen Y, Wang S, et al. The role of STAT3 in leading the crosstalk between human cancers and the immune system[J]. Cancer Lett, 2018, 415: 117–128. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.003 |

| [33] | Li SQ, Cheuk AT, Shern JF, et al. Targeting wild-type and mutationally activated FGFR4 in rhabdomyosarcoma with the inhibitor ponatinib (AP24534)[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8: e76551. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0076551 |

| [34] | Ferrajoli A, Faderl S, Van Q, et al. WP1066 disrupts Janus kinase-2 and induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in acute myelogenous leukemia cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2007, 67: 11291–11299. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0593 |

| [35] | Iwamaru A, Szymanski S, Iwado E, et al. A novel inhibitor of the STAT3 pathway induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells both in vitro and in vivo[J]. Oncogene, 2007, 26: 2435–2444. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1210031 |

| [36] | Oyaizu T, Fung SY, Shiozaki A, et al. Src tyrosine kinase inhibition prevents pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute lung injury[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38: 894–905. DOI:10.1007/s00134-012-2498-z |

| [37] | Gangadhar TC, Clark JI, Karrison T, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of the Src kinase inhibitor saracatinib (AZD0530) in metastatic melanoma[J]. Invest New Drugs, 2013, 31: 769–773. DOI:10.1007/s10637-012-9897-4 |

| [38] | Antonarakis ES, Heath EI, Posadas EM, et al. A phase 2 study of KX2-391, an oral inhibitor of Src kinase and tubulin polymerization, in men with bone-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2013, 71: 883–892. DOI:10.1007/s00280-013-2079-z |

| [39] | Sun X, Li B, Xie B, et al. DCZ3301, a novel cytotoxic agent, inhibits proliferation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma via the STAT3 pathway[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2017, 8: e3111. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2017.472 |

| [40] | Kraskouskaya D, Duodu E, Arpin CC, et al. Progress towards the development of SH2 domain inhibitors[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2013, 21: 3337–3370. |

| [41] | Turkson J, Ryan D, Kim JS, et al. Phosphotyrosyl peptides block STAT3-mediated DNA binding activity, gene regulation, and cell transformation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276: 45443–45455. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M107527200 |

| [42] | Turkson J, Kim JS, Zhang S, et al. Novel peptidomimetic inhibitors of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 dimerization and biological activity[J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2004, 3: 261–269. |

| [43] | Ren Z, Cabell LA, Schaefer TS, et al. Identification of a high-affinity phosphopeptide inhibitor of STAT3[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2003, 13: 633–636. DOI:10.1016/S0960-894X(02)01050-8 |

| [44] | Dourlat J, Valentin B, Liu WQ, et al. New syntheses of tetrazolylmethylphenylalanine and O-malonyltyrosine as pTyr mimetics for the design of STAT3 dimerization inhibitors[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2007, 17: 3943–3946. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.107 |

| [45] | Chen J, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Yang CY, et al. Design and synthesis of a new, conformationally constrained, macrocyclic small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3via 'click chemistry'[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2007, 17: 3939–3942. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.096 |

| [46] | Mandal PK, Limbrick D, Coleman DR, et al. Conformationally constrained peptidomimetic inhibitors of signal transducer and activator of transcription. 3:Evaluation and molecular modeling[J]. J Med Chem, 2009, 52: 2429–2442. DOI:10.1021/jm801491w |

| [47] | Mandal PK, Heard PA, Ren Z, et al. Solid-phase synthesis of STAT3 inhibitors incorporating O-carbamoylserine and O-carbamoylthreonine as glutamine mimics[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2007, 17: 654–656. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.099 |

| [48] | Song H, Wang R, Wang S, et al. A low-molecular-weight compound discovered through virtual database screening inhibits STAT3 function in breast cancer cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102: 4700–4705. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0409894102 |

| [49] | Wei CC, Ball S, Lin L, et al. Two small molecule compounds, LLL12 and FLLL32, exhibit potent inhibitory activity on STAT3 in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells[J]. Int J Oncol, 2010, 38: 279–285. |

| [50] | Fuh B, Sobo M, Cen L, et al. LLL-3 inhibits STAT3 activity, suppresses glioblastoma cell growth and prolongs survival in a mouse glioblastoma model[J]. Br J Cancer, 2009, 100: 106–112. DOI:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604793 |

| [51] | Schust J, Sperl B, Hollis A, et al. Stattic:a small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3 activation and dimerization[J]. Chem Biol, 2006, 13: 1235–1242. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.018 |

| [52] | Zhang Q, Zhang C, He J, et al. STAT3 inhibitor static enhances radiosensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Tumor Biol, 2015, 36: 2135–2142. DOI:10.1007/s13277-014-2823-y |

| [53] | Kim MJ, Nam HJ, Kim HP, et al. OPB-31121, a novel small molecular inhibitor, disrupts the JAK2/STAT3 pathway and exhibits an antitumor activity in gastric cancer cells[J]. Cancer Lett, 2013, 335: 145–152. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.010 |

| [54] | Brambilla L, Genini D, Laurini E, et al. Hitting the right spot:mechanism of action of OPB-31121, a novel and potent inhibitor of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3(STAT3)[J]. Mol Oncol, 2015, 9: 1194–1206. DOI:10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.012 |

| [55] | Oh DY, Lee SH, Han SW, et al. Phase I study of OPB-31121, an oral STAT3 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors[J]. Cancer Res Treat, 2015, 47: 607–615. DOI:10.4143/crt.2014.249 |

| [56] | Ji P, Yuan C, Ma S, et al. 4-Carbonyl-2, 6-dibenzylidenecyclohexanone derivatives as small molecule inhibitors of STAT3 signaling pathway[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2016, 24: 6174–6182. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.070 |

| [57] | Bid HK, Oswald D, Li C, et al. Anti-angiogenic activity of a small molecule STAT3 inhibitor LLL12[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7: e35513. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0035513 |

| [58] | Siddiquee K, Zhang S, Guida WC, et al. Selective chemical probe inhibitor of STAT3, identified through structure-based virtual screening, induces antitumor activity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007, 104: 7391–7396. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0609757104 |

| [59] | Guo W, Wu S, Wang L, et al. Antitumor activity of a novel oncrasin analogue is mediated by JNK activation and STAT3 inhibition[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6: e28487. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0028487 |

| [60] | Hou S, Yi YW, Kang HJ, et al. Novel carbazole inhibits phospho-STAT3 through induction of protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPN6[J]. J Med Chem, 2014, 57: 6342–6353. DOI:10.1021/jm4018042 |

| [61] | Lin L, Hutzen B, Ball S, et al. New curcumin analogues exhibit enhanced growth-suppressive activity and inhibit AKT and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 phosphorylation in breast and prostate cancer cells[J]. Cancer Sci, 2009, 100: 1719–1727. DOI:10.1111/cas.2009.100.issue-9 |

| [62] | Cen L, Hutzen B, Ball S, et al. New structural analogues of curcumin exhibit potent growth suppressive activity in human colorectal carcinoma cells[J]. BMC Cancer, 2009, 9: 99. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-9-99 |

| [63] | Mehmood T, Maryam A, Tian X, et al. Santamarine inhibits NF-κB activation and induces mitochondrial apoptosis in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells via oxidative stress[J]. J Cancer, 2017, 8: 3707–3717. DOI:10.7150/jca.20239 |

| [64] | Kim LH, Khadka S, Shin JA, et al. Nitidine chloride acts as an apoptosis inducer in human oral cancer cells and a nude mouse xenograft model via inhibition of STAT3[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8: 91306–91315. |

| [65] | Vannini N, Lorusso G, Cammarota R, et al. The synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, CDDO-methyl ester, is a potent antiangiogenic agent[J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2007, 6: 3139–3146. DOI:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0451 |

| [66] | Liby KT, Royce DB, Risingsong R, et al. Synthetic triterpenoids prolong survival in a transgenic mouse model of pancreatic cancer[J]. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 2010, 3: 1427–1434. DOI:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0197 |

| [67] | Ling X, Konopleva M, Zeng Z, et al. The novel triterpenoid C-28 methyl ester of 2-cyano-3, 12-dioxoolen-1, 9-dien-28-oic acid inhibits metastatic murine breast tumor growth through inactivation of STAT3 signaling[J]. Cancer Res, 2007, 67: 4210–4218. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3629 |

| [68] | Duan Z, Ames RY, Ryan M, et al. CDDO-Me, a synthetic triterpenoid, inhibits expression of IL-6 and STAT3 phosphorylation in multi-drug resistant ovarian cancer cells[J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2009, 63: 681–689. DOI:10.1007/s00280-008-0785-8 |

| [69] | Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, et al. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB[J]. Genes Dev, 2007, 21: 1396–1408. DOI:10.1101/gad.1553707 |

| [70] | Nkansah E, Shah R, Collie GW, et al. Observation of unphosphorylated STAT3 core protein binding to target dsDNA by PEMSA and X-ray crystallography[J]. FEBS Lett, 2013, 587: 833–839. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.065 |

| [71] | Timofeeva OA, Chasovskikh S, Lonskaya I, et al. Mechanisms of unphosphorylated STAT3 transcription factor binding to DNA[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287: 14192–14200. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.323899 |

| [72] | Huang W, Dong Z, Wang F, et al. A small molecule compound targeting STAT3 DNA-binding domain inhibits cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2014, 9: 1188–1196. DOI:10.1021/cb500071v |

| [73] | Yang E, Henriksen MA, Schaefer O, et al. Dissociation time from DNA determines transcriptional function in a STAT1 linker mutant[J]. Biol Chem, 2002, 277: 13455–13462. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112038200 |

| [74] | Buettner R, Corzano R, Rashid R, et al. Alkylation of cysteine 468 in STAT3 defines a novel site for therapeutic development[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2011, 6: 432–443. DOI:10.1021/cb100253e |

| [75] | Huang W, Dong Z, Chen Y, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 suppress tumor growth, metastasis and STAT3 target gene expression in vivo[J]. Oncogene, 2015, 35: 783–792. |

| [76] | Son DJ, Zheng J, Jung YY, et al. MMPP attenuates non-small cell lung cancer growth by inhibiting the STAT3 DNA-binding activity via direct binding to the STAT3 DNA-binding domain[J]. Theranostics, 2017, 7: 4632–4642. DOI:10.7150/thno.18630 |

| [77] | Timofeeva OA, Gaponenko V, Lockett SJ, et al. Rationally designed inhibitors identify STAT3 N-domain as a promising anticancer drug target[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2007, 2: 799–809. DOI:10.1021/cb700186x |

| [78] | Timofeeva OA, Tarasova NI, Zhang X, et al. STAT3 suppresses transcription of proapoptotic genes in cancer cells with the involvement of its N-terminal domain[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013, 110: 1267–1272. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1211805110 |

| [79] | Levy DE, Darnell JE Jr. STATS:transcriptional control and biological impact[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2002, 3: 651–662. DOI:10.1038/nrm909 |

| [80] | Huang M, Song K, Liu X. AlloFinder: a strategy for allosteric modulator discovery and allosterome analyses[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 46: W451-W458. |

2018, Vol. 53

2018, Vol. 53