抑郁症属于情感性精神障碍, 是一种以持续性心境低落为主要特征的精神疾病综合症。抑郁症是目前世界上最易致残的疾病之一, 也是自杀的主要原因之一。据不完全统计, 目前全世界抑郁症患者的人数约为3.5亿[1], 我国发病率约为4%。世界卫生组织预测, 到2030年, 抑郁症将位居全球疾病总负担排名首位[2]。自杀是我国总人口的第五大死因, 也是15~34岁的青壮年人群的首位死因[3], 而在这些自杀的人群中, 患抑郁症的占了50%~70%[4]。尽管全世界医药专家对抑郁症进行了大量的研究, 但其发病机制至今尚不清楚。

目前, 临床上主要应用选择性5-HT再摄取抑制剂(selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs)治疗抑郁症, 安全性较高, 疗效较好。在已上市的66种抗抑郁药物中, 有34种为SSRIs, 且单胺类递质学说也成为抑郁症治疗的研究重点。但是, 仍有高达50%抑郁症患者对所有目前已有的治疗药物无任何反应, 且单胺假说也暴露出越来越多的局限性[5]。

胆碱能假说于1972年提出[6], 而且发现许多临床应用的抗抑郁药都对烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体有拮抗作用[7], 人们逐渐认识到胆碱能系统在情绪障碍调节过程中的作用。本文将就α4β2亚型烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体与抑郁症的关系做一介绍。

1 中枢乙酰胆碱受体乙酰胆碱作为一种重要的神经递质, 可以通过激动受体而改变神经元兴奋性, 影响突触传递, 诱导突触可塑性并协调神经元组的激发, 在整个外周和中枢神经系统中均发挥着重要作用。20世纪初, 根据乙酰胆碱受体对天然生物碱——毒蕈碱和烟碱的药理学反应特性不同, 将其分为毒蕈碱受体(muscarine acetylcholine receptors, mAChRs)和烟碱受体(nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, nAChRs)。研究发现, 这两类受体在结构和功能上有着巨大差别, 毒蕈碱受体属于G-蛋白偶联、由第二信使介导的受体家族; 而烟碱受体属于离子通道偶联的受体家族, 其激活后主要通过对膜电位的调节而影响细胞功能活动。早期研究表明, 中枢mAChRs激活后介导的效应与认知功能活动有关, 而中枢型nAChRs包括神经节烟碱受体和脑烟碱受体, 由于其分布广泛、作用复杂, 长期以来对其在脑内介导的生物效应认识不足。直到20世纪90年代以后, 才有越来越多的研究表明, 脑内烟碱受体的激活也与认知功能等有关。

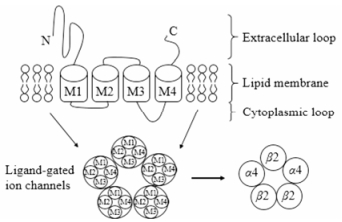

烟碱受体由5个亚单位组成, 呈五角形排列, 中央形成1个离子通道, 主要控制细胞内外的Na+、K+和Ca2+的流动。每个亚单位都含有2个亲水区和4个疏水区, 这4个疏水区分别称为M1、M2、M3和M4, 每个亚单位的M2构成离子通道的内衬面, 见图 1。因为M2螺旋上含有较多的酸性氨基酸残基, 使通道形成负性电位, 对带正电荷的离子具有亲和力, 所以烟碱受体通道是一种选择性的阳离子通道[8]。中枢nAChRs包括脑nAChRs和神经元nAChRs; 外周nAChRs包括成熟型ε-nAChRs和胚胎型γ-nAChRs。烟碱受体由不同的亚单位构成, 至今已确认的17种nAChRs亚单位分别为α1~10、β1~4、δ、ε和γ, 不同亚单位通过不同组合表现出不同的生理学和药理学特征。

|

Figure 1 The pentameric structure of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and the composition of α4β2 nAChRs |

根据已知的17种亚单位的基因结构和DNA序列的相似性, 又将其分为4个亚家族:亚家族Ⅰ (α9、α10)和Ⅱ (α7、α8)的4个亚单位性质相似, 既能单独组成均质五聚体受体, 也能与其他亚单位组合形成异质五聚体受体; 亚家族Ⅲ (α2~α6, β2~β4)是一系列复杂异质五聚体受体的组成成分, 主要分布于各种神经元上; 亚家族Ⅳ (α1、β1、δ、ε和γ)则构成肌肉的nAChRs。在神经系统中, α2位于脚间核; α3和β4位于自主神经节和少数的中枢神经核(缰核、松果体、孤束核等); α4分布很广泛, 位于耳蜗、前庭神经节以及除了纹状体、海马、小脑之外的整个脑区, 尤其在丘脑内的含量最高; α5位于前脑、嗅区、海马、杏仁核、基底节、脑干和脊髓; α6和β3位于躯体感觉神经节和中枢含有胆碱能的神经核; α7位于下丘脑、海马及下丘等部位; β2则存在于整个神经系统。中枢神经系统的功能性受体包括由单种亚单位α7形成的同源五聚体的受体亚型; 由2种受体亚单位组合成的α2β2、α3β2、α4β2和α3β4受体亚型; 由多种受体亚单位组合成的α3β4α5、α1β2α5和α3β2β4α5受体亚型。其中分布最多的是α4β2和α7[9]两种受体亚型, 成为研究的热点。

2 乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体与抑郁症 2.1 胆碱能系统与抑郁症直接相关临床试验表明, 尼古丁等烟碱型乙酰胆碱能化合物是对SSRI无反应抑郁症患者的有效药物[10-13], 并可以增强SSRIs的抗抑郁效果。胆碱能系统的异常与抑郁、躁动、精神异常以及人格改变均有关。人在精神应激状况下, 中枢乙酰胆碱(acetylcholine, ACh)更新加快, ACh促进压力敏感型神经激素和肽的释放, 包括皮质酮、促肾上腺皮质激素(adrenocorticotropic hormone, ACTH)、促肾上腺皮质激素释放因子(corticotropin releasing factor, CRF)。机体内胆碱能和单胺能系统在调节情绪方面有动态交互作用, 也被称为胆碱能与肾上腺素能平衡学说, 前者活性超过后者时引起抑郁; 反之引起躁狂。

人类断层成像研究表明, 抑郁的单相和双相受试者整个脑中的ACh水平和乙酰胆碱受体(acetyl choline receptors, AChRs)数量均有增加[14, 15], 阻断ACh的降解在即使无病史的个体中也能诱导抑郁症状, 在小鼠中仅阻断海马区的ACh降解便能诱导抑郁症状和焦虑样行为[16]。抑郁患者服用中枢拟胆碱药后, 快动眼的潜伏期缩短且ACTH和皮质醇水平升高。拮抗烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体可以有效减轻并发型抑郁和双向抑郁患者的抑郁症状, 增强情绪稳定性[17]。人类中, 吸烟与抑郁症关系密切, 重度抑郁症患者的尼古丁依赖率为50%~60%, 而在普通人群中仅为25%[18, 19]。在对尼古丁的研究中, 研究者认为一口香烟足以使人脑中的高亲和力nAChRs饱和, 吸烟引起的短暂激活可以导致nAChRs活性立即增加, 导致情感症状, 随后在长期吸烟过程中, 由于脱敏反应引起nAChRs数量上的增加以及活性的下降, 又可对抑郁症状有所缓解, 并在戒烟后加重抑郁症状[20]。在动物中最有力的证明即为Flinders敏感型(FSL)大鼠, 该品种大鼠大脑中出现遗传性的ACh水平增加, 表现出很明显的抑郁样症状, 包括运动活性降低、体重减轻、快动眼睡眠增加和认知缺陷[21]。

如果乙酰胆碱水平的改变可引起抑郁症状, 那么有理由推测nAChRs和mAChRs激活状态改变可能是乙酰胆碱信号传导发生改变的机制。胆碱能假说应该更准确地被称为胆碱能单胺能相互作用理论[22], 因为对大脑中任何一种神经递质系统的任何改变都将会对其他系统产生广泛的影响[23]。烟碱类化合物的情绪调节和抗抑郁作用不仅仅是单向的, nAChRs的活化和抑制可能导致不同情况下的抗抑郁作用, 且对不同受体、不同脑区和不同递质系统的影响也会根据个体应激及抑郁的水平而有所不同。

2.2 α4β2亚型在胆碱能调节情绪中的作用大脑中广泛表达α4β2型烟碱胆碱能受体, 提示该亚型可能参与烟碱型药物对大脑的作用。

临床研究显示, 抑郁症患者体内烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体数目无明显变化, 但出现了β2亚型的功能性失活[15], 作用于β2型nAChRs的配基, 如尼古丁(nAChRs非选择性激动剂)[24]、美加明(nAChRs非选择性拮抗剂)[25]、伐尼克兰(α4β2 nAChRs选择性部分激动剂, α3β4和α7激动剂)[26]等在抑郁症患者中具有抗抑郁作用。与之对应, 上述药物及二氢-β-刺桐啶碱(DHβE, α4β2 nAChRs选择性拮抗剂)[27]和金雀花碱(α3β4和α7 nAChRs强激动剂及α4β2 nAChRs部分激动剂)[28]等在临床前研究中也均有抗抑郁的作用。对于β2 nAChRs亚基不敏感的小鼠, 美加明和三环类抗抑郁药阿米替林[27]则失去抗抑郁作用, 提示β2亚基在抗抑郁环节中发挥着重要作用。

另有研究利用α4或β2亚单位缺失小鼠证明了α4β2 nAChRs介导了尼古丁的一系列反应[29]。α4或α7亚基敲除后烟碱电流仍可在大脑内检测到[30], 但这些电流在β2亚基敲除的小鼠中被全面消除[31], 在研究最多的α7和α4β2两种亚型中, β2亚型似乎占据了更不可替代的作用。

3 乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体调节情绪的可能机制乙酰胆碱能系统在情绪调控中发挥着重要作用, 其作用方式类似于一种神经调节剂[32], nAChRs不聚集在与ACh释放部分相对应的突触后膜上, 而是沿着神经元表面和内部(包括突触前末梢)散布, 甚至分布在胞体和轴突上。由于其空间位置分布以及ACh胞外含量与突触间局部清除率的不对应性, 可以认为乙酰胆碱的作用方式为一种缓慢的容积传递, 该理论从电生理角度也得到了证实[33]。

激活nAChRs可以增加谷氨酸、γ-氨基丁酸(γ- aminobutyric acid, GABA)、多巴胺(dopamine, DA)、去甲肾上腺素和5-羟色胺的释放, 且通常是亚型特异性的, 并在不同脑区内略有变化。其中, α7与谷氨酸相关、α4β2与GABA相关[34]、α4/α6β2与多巴胺相关、α3β4与ACh相关, β2亚型在中脑腹侧被盖区还可以调节丘脑-皮层中谷氨酸的释放[35]。突触前烟碱受体活化后, 通过直接[36]或间接[37]激活, 启动细胞内Ca2+信号, 从而有利于整个大脑中的神经递质的释放[38]。

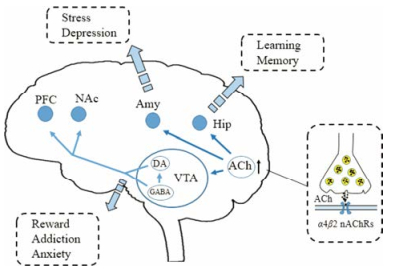

基于高乙酰胆碱引起抑郁症的假说, 部分激动剂仍可以改善抑郁症状的原因被认为是这些化合物干扰了乙酰胆碱信号传导的活性, 而不是作为nAChRs激动剂的活性[39]。目前认为, 脑干中胆碱能神经元的激发与纹状体中胆碱能中间神经元的激发可以显著提高外界环境与奖赏行为之间的联系, 从而有助于快乐情绪的发生, 这可能通过促进DA神经元激活并由谷氨酸能驱动而发生, 并同时使DA终端的阈值降低。接下来在执行任务时需要增强主皮层神经元的前馈激活及特定中间神经元的减少抑制。当海马区ACh水平升高, 可促进相邻神经元协同放电以及节律活动, 提高基础兴奋水平, 随后引起谷氨酸能的激活, 这种因高水平ACh释放而产生的递质传递易化现象, 可能是由突触可塑易化介导。最终乙酰胆碱信号的增强引起了与应激相关的疾病, 如重度抑郁症。不同脑区的乙酰胆碱受体被激活后, 通过影响记忆、奖赏及应激系统等共同发挥情绪调控的作用, 详见图 2。

|

Figure 2 The activation of α4β2 nAChRs in hippocampus (Hip), ventral tegmental area (VTA) and amygdala (Amy) would regulate the state of depression by affect the progress of learning and memory, reward and anxiety, stress respectively. PFC: Prefrontal cortex; NAc: Nucleus accumbens; DA: Dopamine; GABA: γ-Aminobutyric acid; ACh: Acetylcholine |

在抑郁症患者中, 海马体积显著减小[40], 提示患者学习认知功能也可能受到了一定影响。据报道, 尼古丁使小鼠在多项学习记忆测试中都有所提高[41], 但α4或β2亚基敲除后, 这些改善作用就不出现[42, 43], 同时β2敲除后伴随着神经变性增加[44]。可见α4β2烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体在海马神经可塑性中发挥着重要作用。

突触可塑性通常由动作电位等主动跨膜活动调节, 也可以由被动膜特性进行调节。与之对应, nAChRs可以直接调节电压依赖性离子通道, 使其失活, 降低A型K+通道的可用性, 并增加Na+和Ca2+通道的开放; 也可以修饰神经元的电子特性, 通过影响阈值等触发突触可塑性[45]。烟碱型乙酰胆碱受体介导的突触前促进谷氨酸释放作用以及突触后c-fos基因转录协同作用, 共同影响神经元的长期变化[46]。海马区中的nAChRs激动有助于GABA能神经元及谷氨酸能神经元[47]的成熟, 同时通过调节细胞内钙水平, 改变GABA能和谷氨酸能神经元对兴奋性输入的反应, 促进海马区神经元的长时程增强效应。

除了调节神经元活动外, 胆碱能系统还能对神经元发育过程的多个环节发挥调节作用, 包括调节氯转运蛋白表达的时机, 这对于GABA超极化从而抑制中枢神经元是至关重要的[48], 意味着胆碱能系统的扰乱将延迟GABA能介导的从兴奋到抑制的转换。此外, nAChRs对ACh信号传导和神经元通路以及靶点的选择性[49]均具有重要作用。

nAChRs对海马区调控认知的主要作用机制可概括如下:当机体接受外界刺激后, 中枢胆碱能神经系统释放乙酰胆碱, 激活海马区nAChRs, 引起一系列反应, 包括促进海马区GABA能神经元释放谷氨酸, 直接和间接地增强细胞内Ca2+信号, 引起突触后膜去极化及突触前膜神经递质释放, 由nAChRs激活引起的钙信号和去极化激活细胞内信号传导及核内c-fos基因转录, 增强海马区神经元可塑性; 而局部GABA能中间神经元上的nAChRs激活后, 又可直接阻断长时程增强作用(long-term potentiation, LTP)对CA1锥体神经元的诱导; 此外, nAChRs可以在海马早期发育中调控突触由沉默到功能状态的相互转变, 并介导GABA由幼年机体中兴奋性神经递质转变为成年机体中的抑制性神经递质。在整个过程中, nAChRs诱导LTP并以α7 nAChRs-NMDAR依赖的方式增强刺激诱导的LTP, 调控突触可塑性。

3.2 乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体与奖赏、成瘾及焦虑的关系胆碱能系统对于DA的调节作用研究主要集中在成瘾和奖赏相关行为, 其中以尼古丁的成瘾性研究最为广泛[50], 其关键作用区域为腹侧中脑和腹侧被盖区(ventral tegmental area, VTA), 其中的多巴胺能神经元向包括前额叶皮层、杏仁核、纹状体和伏隔核在内的情绪和决策区域输出奖赏信息, 并接受来自前额叶皮层等的兴奋性以及局部GABA能中间神经元的抑制性输入。

多巴胺能系统被认为是尼古丁效应增强的关键[51], 分为涉及药物奖赏和应激反应的中脑边缘多巴胺能通路, 以及运动开始所需的黑质纹状体多巴胺能通路。nAChRs在VTA中可以诱导对DA神经元的兴奋性输入的长时程增强[52], 其动力可能跟星形胶质细胞控制nAChRs激活后突触间的Ca2+浓度升高有关[53], 中脑腹侧神经元表达有大量α7及α4β2型nAChRs[54], 输出胆碱能信号, 并投射到该区域的多巴胺能和GABA能细胞, 调节多巴胺能神经元的突触可塑性, 当其被阻断后, 将会减低尼古丁的奖赏作用。研究证明, 尼古丁刺激β2敲除的小鼠, 其纹状体突触体中DA释放量不再增加[55], 当选择性表达β2 nAChRs进入β2敲除小鼠的中脑多巴胺能神经元后, 即可恢复尼古丁诱发的电生理特性[56], 这揭示了β2 nAChRs在中脑多巴胺神经元中的基本作用。

还有研究表明, α4敲除及低表达时小鼠均表现出较高基线水平的焦虑[57], α4亚基对于尼古丁诱导的奖赏是必需的, 同时参与抗焦虑和运动抑制作用, 但不参与诱导低温。在α4或β2基因突变小鼠中重新引入丢失的亚基, 则可使小鼠恢复对尼古丁的奖赏行为[58]。以上实验充分证明, α4β2 nAChRs在奖赏系统中的重要作用。研究表明, β2 nAChRs的激活可以使多巴胺能神经元从静息模式转换为任何兴奋模式[59], 多巴胺能神经元一旦被激活, α7 nAChRs再将其切换至其他激发输出模式。

胆碱能系统对多巴胺奖赏成瘾的主要作用机制包括:中脑脚桥被盖核(pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus, PPTg)神经元活动增强, 诱导VTA中乙酰胆碱释放及nAChRs激活, 主要由β2 nAChRs介导引起突触后去极化, 增加多巴胺能神经元的动作电位输出频率, 诱导多巴胺能神经元LTP; 随后突触前α7 nAChRs持续活化, 加强谷氨酸在多巴胺能神经元上的传递, 激活突触后谷氨酸受体, 与nAChRs激活的突触去极化共同提供稳定的电压变化, 减少Mg2+对N-甲基-D-天冬氨酸受体(N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor, NMDAR)造成的阻断; 同时GABA能中间神经元上β2受体激活并迅速脱敏, 以减少对多巴胺能神经元的抑制。

3.3 乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体影响应激系统功能磁共振成像研究发现心境障碍患者的杏仁核一直过度激活[60], 杏仁核是介导恐惧反应的脑区, 并与管控学习记忆的海马以及注意力的前额皮层(prefrontal cortex, PFC)共同成为适应和应对应激的关键节点, 分别接受来自BF复合体的胆碱能信号输入, 尤其是内侧间隔和基底核部分, 其活性功能障碍与严重抑郁症密切相关[61]。

研究表明, β2 nAChRs有助于应激诱导后的行为改善, 并可能改善人类抑郁症状[62]。海马通过抑制下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴(the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, HPA axis)进行杏仁核的抑制性反馈[63], 应激导致海马和皮层中的ACh含量增加, 杏仁核中的ACh水平基本不变, 但可以通过激活nAChRs降低基底外侧复合物(basolateral amygdala, BLA)活性[64], 而杏仁核调节肾上腺应激激素和几类神经递质的作用就是由BLA选择性介导的[65], 且降低杏仁核中的nAChRs水平有助于减轻抑郁样反应。

前已述及, ACh可以通过nAChRs和mAChRs的突触前及突触后效应来诱导突触可塑性来调节学习记忆, 这其中也包括对应激事件的记忆, 应激还会诱导海马乙酰胆碱酯酶的mRNA发生选择性剪接从而改变ACh信号传导[66]。胆碱能系统在机体应激后如何导致海马区信号输出目前还没有共识, 但通常认为乙酰胆碱在调节θ振荡中起到关键作用, θ振荡在记忆编码中至关重要, 同时海马的节律紊乱也可能导致抑郁症[67], mAChRs和nAChRs的兴奋性和抑制性传播则可以共同调节节律活动。经c-fos免疫反应检测, 通过nAChRs减少ACh信号传导可以抑制基底外侧杏仁核中的神经元活性[68], ACh同时调节皮质神经元的输出以及持续增强皮层-杏仁核中的谷氨酸能水平。因此认为乙酰胆碱在杏仁核中加强了环境刺激与紧张情绪的关联, 并由此加剧了情感障碍。

胆碱能系统在杏仁核应激过程中的作用主要包括:应激刺激使内侧间隔及基底核部分输出胆碱能信号, 激活基底前脑的胆碱能神经元, 并增加海马和前额皮层中乙酰胆碱的释放, 影响海马区θ振荡和节律, 加重应激与紧张情绪。应激过程中, BLA起到了重要的作用, 而皮质-杏仁核的胆碱输入可通过调控BLA来调节神经递质水平, 促进去甲肾上腺素、谷氨酸及GABA释放, 共同影响神经元的兴奋性。目前应激诱导的乙酰胆碱释放对海马和皮质输出的影响尚不清楚, 但皮质-杏仁核谷氨酸能连接的胆碱能调节可增强环境刺激和应激事件之间的关联。

4 总结与展望综上, 乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体与抑郁症关系密切, 其拮抗剂或部分激动剂可通过阻断ACh信号从而降低人类和啮齿类动物的抑郁样行为[69, 70], 其机制涉及到促进海马区认知功能、增强突触可塑性、刺激奖赏成瘾系统并影响应激反应系统等。但尽管高胆碱能假说被认为可以诱发人类抑郁, 却有研究指出小鼠纹状体中胆碱能水平降低也会导致抑郁症状[71], 因此要重视ACh在不同脑区的甚至相反的异质效应, 且不同效应要建立在其基线条件上进行考虑。

现有文献表明, 胆碱能系统在情绪调控中发挥着重要作用, 激活α7 nAChRs且拮抗α4β2 nAChRs的化合物在抗抑郁方面展现出良好发展趋势[72], 但仍需要更多的研究来确定关于海马、PFC、杏仁核中胆碱能系统与情绪关系的临床前研究是否与人类抑郁症患者中ACh的表现一致, 从而进一步揭示胆碱能系统与情绪和行为相关的生理机制, 并为乙酰胆碱α4β2型受体调节剂早日开发为抗抑郁新药提供理论基础和实践方向。

| [1] | GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015[J]. Lancet, 2017, 388: 1603-1658. |

| [2] | Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder:results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R)[J]. JAMA, 2003, 289: 3095–3105. DOI:10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 |

| [3] | Liu XQ, Bai ZJ. A meta-analysis of risk factors for suicide in patients with major depression disorder[J]. Chin J Clin Psychol (中国临床心理学杂志), 2014, 22: 291–294. |

| [4] | Guo JM, Zeng KB. Risk factors for suicidal behaviors in Chinese population with depression:a meta analysis[J]. J Chongqing Med Univ (重庆医科大学学报), 2013, 38: 1495–1499. |

| [5] | Khan H, Amin S, Patel S. Targeting BDNF modulation by plant glycosides as a novel therapeutic strategy in the treatment of depression[J]. Life Sci, 2018, 196: 18–27. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2018.01.013 |

| [6] | Janowsky DS, El-Yousef MK, Davis JM, et al. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression[J]. Lancet, 1972, 2: 632–635. |

| [7] | Shytle RD, Silver AA, Lukas RJ, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as targets for antidepressants[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2002, 7: 525–535. DOI:10.1038/sj.mp.4001035 |

| [8] | Unwin N. Acetylcholine receptor channel imaged in the open state[J]. Nature, 1995, 373: 37–43. DOI:10.1038/373037a0 |

| [9] | Wang X, Wang YH, Liu X, et al. Construction of the brain-targeting drug carrier through imprinting of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2017, 52: 488–493. |

| [10] | Tummala R, Desai D, Szamosi J, et al. Safety and tolerability of dexmecamylamine (TC-5214) adjunct to ongoing antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and an inadequate response to antidepressant therapy:results of a long-term study[J]. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2015, 35: 77–81. DOI:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000269 |

| [11] | Schnoll RA, Leone FT, Hitsman B. Symptoms of depression and smoking behaviors following treatment with transdermal nicotine patch[J]. J Addict Dis, 2013, 32: 46–52. DOI:10.1080/10550887.2012.759870 |

| [12] | Rejasgutiérrez J, Bruguera E, Cedillo S. Modelling a budgetary impact analysis for funding drug-based smoking cessation therapies for patients with major depressive disorder in Spain[J]. Eur Psychiatry, 2017, 45: 41–49. DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.027 |

| [13] | Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Martin RA, et al. Varenicline versus nicotine patch with brief advice for smokers with substance use disorders with or without depression:effects on smoking, substance use and depressive symptoms[J]. Addiction, 2017, 112: 1808–1820. DOI:10.1111/add.13861 |

| [14] | Hannestad JO, Cosgrove KP, Dellagioia NF, et al. Changes in the cholinergic system between bipolar depression and euthymia as measured with[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2013, 74: 768–776. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.004 |

| [15] | Saricicek A, Esterlis I, Maloney KH, et al. Persistent β2*-nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptor dysfunction in major depressive disorder[J]. Am J Psychiatry, 2012, 169: 851–859. DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101546 |

| [16] | Mineur YS, Obayemi A, Wigestrand MB, et al. Cholinergic signaling in the hippocampus regulates social stress resilience and anxiety-and depression-like behavior[J]. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A, 2013, 110: 3573–3578. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1219731110 |

| [17] | Ma HY. Progress in clinical application of new antidepressants[J]. Pract J Med Pharm (实用医药杂志), 2013, 30: 940–944. |

| [18] | Psychiatrists RCO. Smoking and mental health[J]. Revista Medica De Chile, 2013, 131: 873–880. |

| [19] | Smith PH, Mazure CM, Mckee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population[J]. Tob Control, 2014, 23: e147–e153. DOI:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466 |

| [20] | Esterlis I, Ranganathan M, Bois F, et al. In vivo evidence for β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit upregulation in smokers as compared with nonsmokers with schizophrenia[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2014, 76: 495–502. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.11.001 |

| [21] | Magara S, Holst S, Lundberg S, et al. Altered explorative strategies and reactive coping style in the FSL rat model of depression[J]. Front Behav Neurosci, 2015, 9: 89. |

| [22] | Owope TE, Ishola IO, Akinleye MO, et al. Antidepressant effect of Cnestis ferruginea Vahl ex DC (Connaraceae):involvement of cholinergic, monoaminergic and L-arginine-nitric oxide pathways[J]. Drug Res, 2016, 66: 235–245. DOI:10.1055/s-00023610 |

| [23] | Chen L, Liu H, Chen JL, et al. Anti-depressive mechanism of Fufang Chaigui prescription based on neuroendocrine hormone and metabolomic correlation analysis[J]. China J Chin Mater Med (中国中药杂志), 2015, 40: 4080–4087. |

| [24] | Tidey JW, Pacek LR, Koopmeiners JS, et al. Effects of 6-week use of reduced-nicotine content cigarettes in smokers with and without elevated depressive symptoms[J]. Nicotine Toba Res, 2017, 19: 59–67. DOI:10.1093/ntr/ntw199 |

| [25] | Aboul-Fotouh. Behavioral effects of nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine in a rat model of depression:prefrontal cortex level of BDNF protein and monoaminergic neurotransmitters[J]. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2015, 232: 1095–1105. DOI:10.1007/s00213-014-3745-5 |

| [26] | Cinciripini PM, Karam-Hage M. Study suggests varenicline safe and effective among adults with stable depression[J]. Evid Based Med, 2014, 19: 92. DOI:10.1136/eb-2013-101619 |

| [27] | Rabenstein RL, Caldarone BJ, Picciotto MR. The nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine has antidepressant-like effects in wild-type but not β2-or α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout mice[J]. Psychopharmacology, 2006, 189: 395–401. DOI:10.1007/s00213-006-0568-z |

| [28] | Mineur YS, Somenzi O, Picciotto MR. Cytisine, a partial agonist of high-affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, has antidepressant-like properties in male C57BL/6J mice[J]. Neuropharmacology, 2007, 52: 1256–1262. DOI:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.01.006 |

| [29] | Picciotto MR, Caldarone BJ, Brunzell DH, et al. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout mice:physiological and behavioral phenotypes and possible clinical implications[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2001, 92: 89–108. DOI:10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00161-9 |

| [30] | Klink R, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Zoli M, et al. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei[J]. J Neurosci, 2001, 21: 1452–1463. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001 |

| [31] | Marubio LM, del Mar Arroyo-Jimenez M, Cordero-Erausquin M, et al. Reduced antinociception in mice lacking neuronal nicotinic receptor subunits[J]. Nature, 1999, 398: 805–810. DOI:10.1038/19756 |

| [32] | Picciotto MR, Higley MJ, Mineur YS. Acetylcholine as a neuromodulator:cholinergic signaling shapes nervous system function and behavior[J]. Neuron, 2012, 76: 116–129. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.036 |

| [33] | Ren J, Qin C, Hu F, et al. Habenula "cholinergic" neurons corelease glutamate and acetylcholine and activate postsynaptic neurons via distinct transmission modes[J]. Neuron, 2011, 69: 445–452. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.038 |

| [34] | Nirogi R, Goura V, Abraham R, et al. α4β2* neuronal nicotinic receptor ligands (agonist, partial agonist and positive allosteric modulators) as therapeutic prospects for pain[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2013, 712: 22–29. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.04.021 |

| [35] | Schlicker E, Feuerstein T. Human presynaptic receptors[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2016, 172: 1–21. |

| [36] | Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, et al. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine[J]. Nature, 1996, 383: 713–716. DOI:10.1038/383713a0 |

| [37] | Wang BW, Liao WN, Chang CT, et al. Facilitation of glutamate release by nicotine involves the activation of a Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway in rat prefrontal cortex nerve terminals[J]. Synapse, 2006, 59: 491–501. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2396 |

| [38] | Wall TR, Henderson BJ, Voren G, et al. TC299423, a novel agonist for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2017, 8: 641. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2017.00641 |

| [39] | Mineur YS, Picciotto MR. Nicotine receptors and depression:revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis[J]. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2010, 31: 580–586. DOI:10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004 |

| [40] | Schriber RA, Anbari Z, Robins RW, et al. Hippocampal volume as an amplifier of the effect of social context on adolescent depression[J]. Clin Psychol Sci, 2017, 5: 632–649. DOI:10.1177/2167702617699277 |

| [41] | Holliday ED, Nucero P, Kutlu MG, et al. Long-term effects of chronic nicotine on emotional and cognitive behaviors and hippocampus cell morphology in mice:comparisons of adult and adolescent nicotine exposure[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2016, 44: 2818–2828. DOI:10.1111/ejn.2016.44.issue-10 |

| [42] | Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Léna C, et al. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain[J]. Nature, 1995, 374: 65–67. DOI:10.1038/374065a0 |

| [43] | Ross SA, Wong JY, Clifford JJ, et al. Phenotypic characterization of an alpha 4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knock-out mouse[J]. J Neurosci, 2000, 20: 6431–6441. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06431.2000 |

| [44] | Zoli M, Picciotto M R, Ferrari R, et al. Increased neurodegeneration during ageing in mice lacking high-affinity nicotine receptors[J]. EMBO J, 1999, 18: 1235–1244. DOI:10.1093/emboj/18.5.1235 |

| [45] | Fuenzalida M, Pérez M, Arias HR. Role of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors on synaptic plasticity and neurological diseases[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2016, 22: 2004–2014. DOI:10.2174/1381612822666160127112021 |

| [46] | Dehkordi O, Rose JE, Dávilagarcía MI, et al. Neuroanatomical relationships between orexin/hypocretin-containing neurons/nerve fibers and nicotine-induced c-Fos-activated cells of the reward-addiction neurocircuitry[J]. J Alcohol Drug Depend, 2017, 5: 273. |

| [47] | Lozada AF, Wang X, Gounko NV, et al. Glutamatergic synapse formation is promoted by alpha7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[J]. J Neurosci, 2012, 32: 7651–7661. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6246-11.2012 |

| [48] | Liu Z, Neff RA, Berg DK. Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development[J]. Science, 2006, 314: 1610–1613. DOI:10.1126/science.1134246 |

| [49] | Role LW, Berg DK. Nicotinic receptors in the development and modulation of CNS synapses[J]. Neuron, 1996, 16: 1077–1085. DOI:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80134-8 |

| [50] | Norman H, D'Souza MS. Endogenous opioid system:a promising target for future smoking cessation medications[J]. Psychopharmacology, 2017, 234: 1–24. DOI:10.1007/s00213-016-4465-9 |

| [51] | Tolu S, Marti F, Morel C, et al. Nicotine enhances alcohol intake and dopaminergic responses through β2* and β4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 45116. DOI:10.1038/srep45116 |

| [52] | Puddifoot CA, Wu M, Sung RJ, et al. Ly6h regulates trafficking of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine-induced potentiation of glutamatergic signaling[J]. J Neurosci, 2015, 35: 3420–3430. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3630-14.2015 |

| [53] | Navarrete M, Perea G, Maglio L, et al. Astrocyte calcium signal and gliotransmission in human brain tissue[J]. Cerebral Cortex, 2013, 23: 1240–1246. DOI:10.1093/cercor/bhs122 |

| [54] | Maskos U. Role of endogenous acetylcholine in the control of the dopaminergic system via nicotinic receptors[J]. J Neurochem, 2010, 114: 641–646. DOI:10.1111/jnc.2010.114.issue-3 |

| [55] | Grady SR, Meinerz NM, Cao J, et al. Nicotinic agonists stimulate acetylcholine release from mouse interpeduncular nucleus:a function mediated by a different nAChR than dopamine release from striatum[J]. J Neurochem, 2001, 76: 258–268. |

| [56] | Maskos U, Molles BE, Pons S, et al. Nicotine reinforcement and cognition restored by targeted expression of nicotinic receptors[J]. Nature, 2005, 436: 103–107. DOI:10.1038/nature03694 |

| [57] | Pang X, Liu L, Ngolab J, et al. Habenula cholinergic neurons regulate anxiety during nicotine withdrawal via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[J]. Neuropharmacology, 2016, 107: 294–304. DOI:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.03.039 |

| [58] | Grenhoff J, Aston-Jones G, Svensson TH. Nicotinic effects on the firing pattern of midbrain dopamine neurons[J]. Acta Physiol Scand, 1986, 128: 351–358. DOI:10.1111/apha.1986.128.issue-3 |

| [59] | Mameliengvall M, Evrard A, Pons S, et al. Hierarchical control of dopamine neuron-firing patterns by nicotinic receptors[J]. Neuron, 2006, 50: 911–921. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.007 |

| [60] | Saleh A, Potter GG, Mcquoid DR, et al. Effects of early life stress on depression, cognitive performance and brain morphology[J]. Psychol Med, 2017, 47: 171–181. DOI:10.1017/S0033291716002403 |

| [61] | Young KD, Siegle GJ, Misaki M, et al. Altered task-based and resting-state amygdala functional connectivity following real-time fMRI amygdala neurofeedback training in major depressive disorder[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2018, 5: 691–703. |

| [62] | Pandya AA. Desformylflustrabromine:a novel positive allosteric modulator for beta2 subunit containing nicotinic receptor sub-types[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2016, 22: 2057–2063. DOI:10.2174/1381612822666160127113159 |

| [63] | Fan WH, Yu F, Yao JP. Effect of Chaihu Shugan on hippocampal regulation of HPA axis in chronic stress depression model rats[J]. J Basic Chin Med (中国中医基础医学杂志), 2015, 21: 50–52. |

| [64] | Mineur YS, Fote GM, Blakeman S, et al. Multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in the mouse amygdale regulate affective behaviors and response to social stress[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2016, 41: 1579–1587. DOI:10.1038/npp.2015.316 |

| [65] | Zhang J, Mcdonald AJ. Light and electron microscopic analysis of enkephalin-like immunoreactivity in the basolateral amygdala, including evidence for convergence of enkephalin-containing axon terminals and norepinephrine transporter-containing axon terminals onto common targets[J]. Brain Res, 2016, 1636: 62–73. DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.045 |

| [66] | Femenía T, Gómezgalán M, Lindskog M, et al. Dysfunctional hippocampal activity affects emotion and cognition in mood disorders[J]. Brain Res, 2012, 1476: 58–70. DOI:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.053 |

| [67] | Xu X, Zheng C, An L, et al. Effects of dopamine and serotonin systems on modulating neural oscillations in hippocampus-prefrontal cortex pathway in rats[J]. Brain Topogr, 2016, 29: 539–551. DOI:10.1007/s10548-016-0485-3 |

| [68] | Shytle RD, Silver AA, Sheehan KH, et al. Neuronal nicotinic receptor inhibition for treating mood disorders:preliminary controlled evidence with mecamylamine[J]. Depress Anxiety, 2002, 16: 89–92. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6394 |

| [69] | Han J, Wang D, Liu S, et al. Cytisine, a partial agonist of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduced unpredictable chronic mild stress-induced depression-like behaviors[J]. Biomol Ther (Seoul), 2016, 24: 291–297. DOI:10.4062/biomolther.2015.113 |

| [70] | Zhang HK, Eaton JB, Fedolak A, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel hybrids of highly potent and selective α4β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) partial agonists[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2016, 124: 689–697. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.016 |

| [71] | Warnerschmidt JL, Schmidt EF, Marshall JJ, et al. Cholinergic interneurons in the nucleus accumbens regulate depression-like behavior[J]. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109: 11360–11365. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1209293109 |

| [72] | Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at α4β2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2006, 70: 801–805. DOI:10.1124/mol.106.025130 |

2018, Vol. 53

2018, Vol. 53