炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)是一种慢性易复发的炎症性疾病, 症状主要为持续性的腹泻、腹痛、直肠出血、发热和体重下降, 且有着明显的活动期和缓解期交替的现象[1, 2]。IBD在西方发达国家发病率最高, 我国近年来IBD发病率逐年上升趋势明显, 已成为消化系统的常见病[3]。目前世界上还没有能够彻底治愈IBD的药物, 治疗的主要目的是减轻症状、延长缓解期、预防复发、提高患者的生活质量[4]。

IBD主要包括溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)[5]和克罗恩病(Crohn’s disease, CD)[6]。UC是结肠黏膜层和黏膜下层的连续性炎症; 而CD可见于全消化道, 为非连续性的全层炎症, 最常见部位为末端回肠、结肠和肛周。IBD的发病机制尚不清楚[7], 一般认为与遗传基因、环境和免疫异常等因素有关:基因和环境因素在肠道诱导激活免疫系统后, 引起了过度的不可控的炎症反应并一直持续, 进而破坏肠道管壁, 就可能产生IBD的临床症状。

目前已上市的用于治疗炎症性肠病的药物主要可分为四大类[8]: ① 5-氨基水杨酸(5-ASA)类(包括为避免5-ASA严重的首过消除效应而设计的各种前药), 是IBD的一线治疗药物, 但往往只对轻度至中度的患者有效, 且容易产生耐药性; ②糖皮质激素, 适用于中重度IBD的治疗, 但由于其不良反应和耐受性, 往往只能短期使用; ③抗生素, 如环丙沙星、甲硝唑、万古霉素、利福昔明, 主要用于细菌引起的并发感染的IBD, 使用范围有限; ④免疫抑制剂, 包括大分子的单克隆抗体和小分子免疫抑制剂, 主要用于5-ASA及糖皮质激素治疗不起作用或疗效不佳的患者。

免疫抑制剂中的单抗药物是目前最为有效的IBD药物, 但是这类药物均需注射使用, 而且生产和治疗成本高。另外, 长期使用易产生由于免疫原性而引起的耐药性及其他的不良反应[9, 10]。传统的小分子免疫抑制剂(如硫唑嘌呤、环孢霉素、6-巯基嘌呤、甲氨蝶呤、他克莫司)都是上市已久的药物, 一般只用于病症缓解期的维持, 但常伴有显著的不良反应, 而且往往在炎症突然复发时无效。事实上, 自从单抗药物上市以来, 还没有用于治疗IBD的小分子药物能够获批上市。但相比于单抗药物, 小分子药物具有生产成本低、容易制成口服制剂、不存在免疫原性等优势。因此, 针对IBD的小分子免疫抑制剂已成为近年来研发的热点[11, 12], 目前已有若干具有潜力的新分子处于临床Ⅱ、Ⅲ期研究阶段(表 1)。本文将对这方面的进展进行综述, 希望对读者有所启发。

| Table 1 Phase Ⅱ and Ⅲ clinic trials of new small molecule immunosuppressants for IBD (2012-2017). 1With active skin extra- intestinal manifestations |

炎症是免疫系统过度表达后的一种病理表现。炎症灶是大量免疫细胞不断积聚、增殖、滞留、浸润的结果。激活的免疫细胞可以释放大量的促炎性细胞因子, 这些促炎因子又可诱导细胞产生更多的促炎因子和黏性分子, 进而招募更多的免疫细胞向炎症部位聚集, 导致炎症反应加重。针对IBD炎症的新药研发, 目前主要集中在两个研究方向:以免疫细胞向肠道的积聚过程为抑制靶点的方向和以促炎因子及其生成过程为抑制靶点的方向, 以下将分别进行归纳。

1 抑制免疫细胞积聚过程的小分子IBD新药研发进展吸收更多的免疫细胞进入受损的肠上皮是IBD中炎症和组织损伤过程的关键步骤。免疫细胞需要由血液运输到炎症部位附近, 再穿过血管壁, 附着到受损组织细胞上, 发挥免疫功能。抑制此过程是IBD新药研发的一个重要方向[13]。

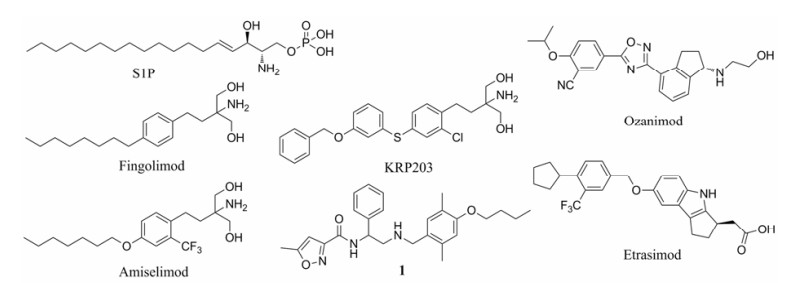

1.1 S1P受体激动剂在淋巴细胞从次级淋巴器官进入血液的过程中, 1-磷酸鞘氨醇(S1P, 图 1)起到关键作用, 调控S1P参与的生理过程, 可以阻止淋巴细胞进入血液, 也就使其不能移动到炎症部位, 从而减轻炎症反应[14, 15]。

|

Figure 1 S1P, agonists of S1P receptors, and inhibitor of S1P lyase |

S1P受体属于G蛋白偶联受体, 目前已知的有5种: S1P1~S1P5。S1P受体激动剂可以持续激活细胞膜表面的S1P受体, 从而诱发其内陷到细胞浆中。在表面的S1P受体内陷消失后, 淋巴细胞就不能识别环境中的S1P, 从而无法进入血液达到炎症部位。S1P1激动剂芬戈莫德(fingolimod, FTY720, 图 1)就是基于此机制治疗多发性硬化症的上市药物, 但其在临床使用中发现患者有心律减缓的不良反应风险, 这可能与其在激动S1P1的同时也激动其他S1P受体(特别是S1P3)有关[16]。在IBD的新药研制上,KRP203[17]和amiselimod (MT-1303)[18]也都是进入Ⅱ期临床的S1P受体激动剂, 其结构与芬戈莫德类似, 但是诺华已经终止了KRP203的Ⅱ期UC临床试验(原因未公开), 而Biogen出于研发优先级的考虑也暂停了amiselimod对CD的继续研究。Ozanimod (RPC-1063)是选择性的以S1P1和S1P5为靶标的激动剂[19], 目前正由Celgene公司同时推进UC和CD的Ⅱ期临床试验。其中针对中重度成年UC患者的阶段性治疗结果显示, 与安慰剂组相比ozanimod只取得了略高的临床缓解率, 但这被认为可能与试验规模有限或者观察时间不够长有关[20], 目前此Ⅱ期临床试验仍在继续中。而其CD的Ⅱ期临床试验尚未有结果披露。另外, etrasimod (APD334)是S1P1、S1P4、S1P5的选择性激动剂[21], 正由Arena Pharmaceuticals公司进行Ⅱ期临床研究。

1.2 S1P裂解酶抑制剂淋巴细胞从次级淋巴器官外排的过程中, 不仅需要通过S1P受体识别环境中的S1P, 还需要依照S1P的浓度梯度牵引, 才能从输出淋巴管排出。S1P裂解酶可以通过降解S1P来维持其浓度梯度。抑制S1P裂解酶就破坏了S1P的浓度梯度, 从而能将淋巴细胞关在次级淋巴器官中, 无法进入血液。2016年, Dinges等[22]报道了一种尚处于早期研究阶段的新型S1P裂解酶抑制剂(1, 图 1), 但其代谢稳定性还有待提高。

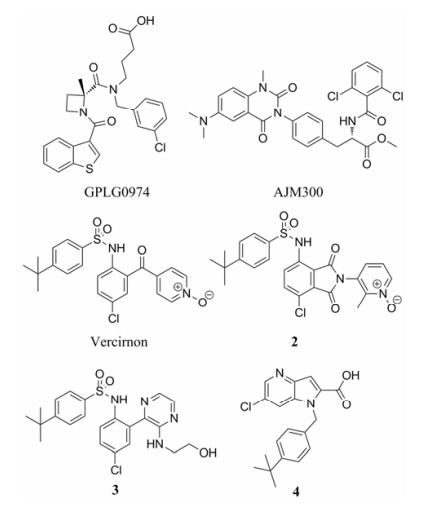

1.3 FFA受体抑制剂FFA2 (free fatty acid receptor 2, GPR43)是肠道产生的短链脂肪酸的受体之一, 免疫细胞可以表达FFA2, 特别是嗜中性粒细胞可以通过识别短链脂肪酸, 实现向肠道的转移。GLPG0974 (图 2)是Galapagos公司研发的FFA2抑制剂[23], 已经完成了一项针对轻中度UC的Ⅱa期临床试验, 结果显示相对于安慰剂组尽管其可以抑制嗜中性粒细胞的增殖, 但患者的症状并没有与安慰剂组表现出显著性的差别[24]。与其相似的, Galapagos还开发了另一个FFA受体GPR84的抑制剂GLPG1205 (无具体结构报道), 并进行了中重度UC的Ⅱa期临床试验, 尽管其药代动力学、安全性及耐受性良好, 但与安慰剂组相比未表现出显著性差异。Galapagos已经终止了GLPG1205对UC适应证的开发[25]。

|

Figure 2 IBD immunosuppressants targeting FFA, α4β1/α4β7 integrin, and CCR9 |

黏附分子在免疫细胞从脉管系统到局部组织的转移过程中起到关键作用。其中, 位于免疫细胞表面的整合素, 可以介导其与内皮细胞及黏膜外皮细胞的紧密黏附。通过抑制整合素的活性, 能够抑制免疫细胞向病原附近移动积聚的过程, 进而使炎症得到改善。Biogen开发的那他珠单抗(natalizumab)是FDA批准上市的中重度CD治疗药物。作用机制是识别并抑制含α4亚基的整合素, 但在α4β1 (存在于血脑屏障)和α4β7 (存在于肠道)亚型整合素间没有选择性。临床使用后, 发现那他珠单抗有并发进行性多灶性白质脑病的风险, 这被认为与抑制脑部的α4β1整合素导致脑部感染有关。针对这一问题, 武田制药开发了α4β7的选择性抗体维多珠单抗(vedolizumab), 并且已经被FDA批准上市, 用于中重度UC和CD的治疗[9]。

α4整合素的口服小分子抑制剂AJM300 (caro tegrast methyl, 图 2)[26]已经在日本完成了针对既往使用美沙拉嗪或糖皮质激素不敏感或不耐受的活动期中度UC成年患者的Ⅱ期临床试验, 据报道比安慰剂组表现出显著性的疗效, 并且尚未发现任何严重不良反应(如进行性多灶性白质脑病等)[27]。目前正由EA Pharma推进Ⅲ期临床研究。之前, AJM300也针对活动期CD完成了Ⅱ/Ⅲ期临床试验, 但没有详细的试验结果披露[28], 其后也没有开展CD的进一步临床试验。处在Ⅱ期临床阶段的小分子α整合素抑制剂还有EA Pharma的另一个化合物E6007, 以及Toray Industries的TRK-170, 但这两个分子的结构信息等都没有具体的报道。对于以治疗IBD为目的的小分子整合素抑制剂的开发也还有一些尚处于早期研究阶段的报道[29-32]。

1.5 CCR9抑制剂CCL25是主要在胸腺细胞和肠道外皮细胞中表达的细胞因子。在肠部发生炎症时, 其表达显著增高, 通过与其受体CCR9 (位于淋巴细胞表面)的相互作用驱动淋巴细胞向肠道组织的移动。CCR9抑制剂可以阻断CCR9-CCL25相互作用, 防止淋巴细胞向肠道组织的移动, 进而缓解肠道炎症[33]。

Vercirnon (GSK-1605786, CCX282-B, 图 2)是CCR9抑制剂[34], 尽管其在中重度CD的Ⅱ期临床中获得成功[35], 但在Ⅲ期临床上相比安慰剂组并没有表现出显著疗效[36], 这使得葛兰素史克公司停止了对其的后续研发(包括其对UC的临床试验)。尽管如此, 仍有很多新的CCR9抑制剂正在研发当中。

Vercirnon失败的原因, 一般被认为是其较差的物理化学性质导致的口服和皮下注射的药代动力学问题, 从而不能对CCR9进行持续性抑制。目前已有一些研究以此为着眼点, 筛选新的CCR9抑制剂, 或者对vercirnon进行进一步的结构改造, 并且发现了几个相比vercirnon具有优势的化合物(图 2, 2[37]、3[38]、4[39]), 但这些化合物尚处于早期临床前研究阶段。

2 抑制促炎因子及其生成过程的小分子IBD新药研发进展IBD作为慢性的炎症性疾病, 与体内长期分泌过量的促炎细胞因子(proinflammatory cytokine)相关。促炎因子包括IL-2、IL-6、IL-8、IL-12、IL-17、IL-23、IFN-γ、肿瘤坏死因子TNF-α、巨噬细胞移动抑制因子(MIF)等, 其过量生成打破了体内与抗炎细胞因子(anti-inflammatory cytokine, 如IL-10、TGF-β1、PGE2等)的平衡, 从而导致炎症的产生。抑制与促炎因子相关的通路也是IBD新药研发的一个重要方向。

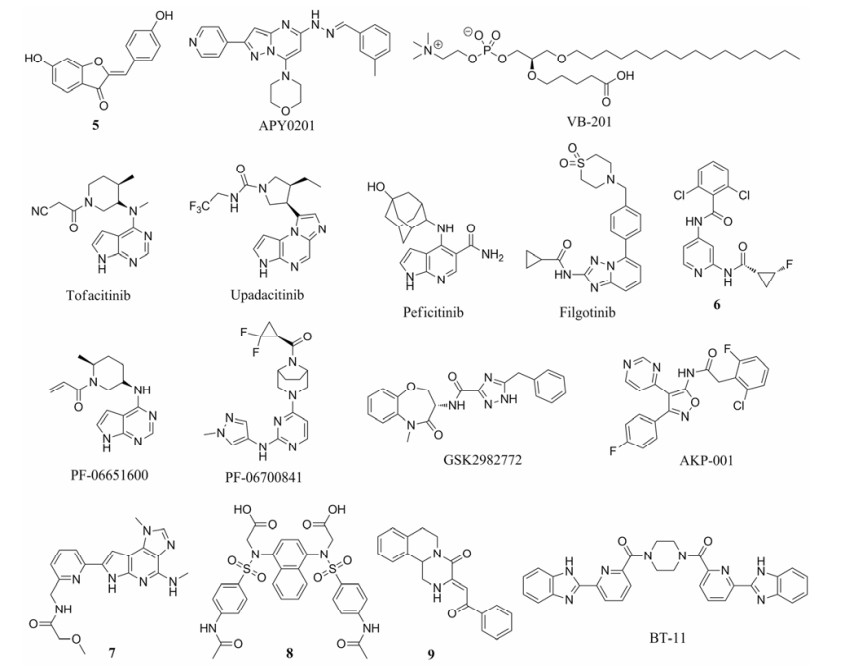

2.1 TNF-α抑制剂肿瘤坏死因子TNF-α是IBD中主要的促炎因子, 由单核细胞和结肠外皮细胞分泌, 可以在结肠外皮上诱导产生更多其他的促炎因子和黏性分子, 使炎症过程一直持续。TNF-α抑制剂通过抑制其诱导的促炎因子和吸附性分子的表达, 达到治疗慢性炎症性疾病的目的[40]。抗TNF-α抗体是目前为止最有效的IBD治疗药物, 如已上市的英夫利昔单抗(infliximab)、阿达木单抗(adalimumab)、赛妥珠单抗(certolizumab)、戈利木单抗(golimumab)。但针对TNF-α的小分子IBD药物开发还没有进入临床研究的例子, 这可能是由于TNF-α的作用机制比较复杂, 不易找到单一的小分子化合物抑制其在IBD中的多种促炎途径。2017年, Kim等[41]在他们前期研究的基础上, 发现化合物5 (图 3)可以抑制TNF-α诱导的一系列生化过程(如: ROS生成、NF-κB和AP-1的转录活性、ICAM-1和MCP-1表达、单核细胞对结肠上皮细胞的粘附), 还能抑制LPS诱导的TNF-α基因表达, 并缓解TNBS诱导的大鼠肠道溃疡[42]。

|

Figure 3 IBD immunosuppressants targeting pathways of proinflammatory cytokines |

IL-12、IL-23是促炎因子, 可以促进T细胞的活化, 加重炎症反应。优特克诺单抗(ustekinumab)是已上市的治疗银屑病的药物, 2016年被FDA批准也可用于中重度CD的治疗。其可以与IL-12及IL-23的p40亚基结合, 从而抑制IL-12及IL-23诱导的一系列下游通路。2014年, 味之素公司报道了小分子化合物APY0201 (图 3), 可以抑制IL-12及IL-23的上游靶标分子PIKfyve (protein phosphoinositide kinase, FYVE finger-containing), 并且在IBD小鼠模型上表现出显著缓解效果[43]。

2.3 Toll样受体相关的抑制剂Toll样受体是免疫细胞膜上用于识别疾病相关分子的一类受体, 其活化后可以激活细胞内促炎因子的产生。VB-201 (图 3)是VBL公司研发的氧化卵磷脂类似物, 用醚键替换了与甘油片段连接的酯键, 增加了对体内酯水解酶的稳定性[44]。研究发现VB-201对炎症具有双重抑制机制:既可以抑制Toll样受体4的共受体和Toll样受体2, 并调控下游的一系列可诱导促炎因子产生的信号通路[45]; 还可以抑制单核细胞向炎症部位的趋化移动[46] (具体的分子机制尚未明确[47])。2014年, VB-201完成了一项针对UC的Ⅱ期临床试验, 目前还没有公开具体的结果, 也没有进一步开展临床试验的报道。

2.4 Janus激酶(JAKs)抑制剂促炎因子诱导炎症产生时, 并不直接进入细胞, 而是在细胞表面与相应的受体结合, 再通过细胞内的JAK-STAT通路将信号传递给细胞核, 引发炎症。存在于细胞质中的Janus激酶(JAK)参与了这一过程。抑制JAK的活性, 就能够抑制JAK-STAT通路, 从而对炎症进行调控[48, 49]。JAK家族由4种非受体型酪氨酸蛋白激酶组成的, 分别是JAK1、JAK2、JAK3和TYK2。

托法替布(tofacitinib, 图 3)是2012年FDA批准上市的治疗中重度活动期类风湿性关节炎的药物, 由辉瑞公司研发, 用于对甲氨蝶呤不敏感或不耐受的成人患者。托法替布对JAK1和JAK3有较强抑制作用, 对JAK2的抑制作用稍弱, 因此可以干扰相应的JAK-STAT信号通路, 进而影响DNA的转录过程。在2012至2016年间, 辉瑞也开展了3个托法替布针对中重度UC的Ⅲ期临床试验, 试验结果显示相对于安慰剂组, 托法替布确实有显著性的疗效[50]; 目前正在招募开展另两个Ⅲ期临床试验, 研究长期用药疗效和弹性的用药计量。另外, 托法替布也进行了中重度CD的Ⅱ期临床试验, 尽管在高给药剂量组中患者的一些理化指标有所改善, 但是病情的治疗效果并没有与安慰剂组有显著性的差异[51]; 2015年辉瑞宣布放弃推进托法替布对CD的Ⅲ期临床试验。

如果能够得到FDA的批准, 托法替布将成为治疗中重度UC的首个JAK抑制剂。但其在临床试验中表现出了高于安慰剂组的不良反应, 如严重感染、肿瘤等, 这可能与其对JAK1-3的抑制选择性不高、全面抑制免疫有关。例如, 抑制JAK2被认为可能导致贫血、血小板减少症、中性粒细胞减少症等不良反应。这也就促使产学界开发新一代的JAK抑制剂用于IBD的治疗, 其中的一些已经进入了临床试验阶段(图 3)。Upadacitinib (ABT-494)是JAK1的选择性抑制剂, 正由艾伯维公司推进临床试验, 在一项新近完成的针对中重度CD的Ⅱ期临床试验中[52], 对于既往接受传统免疫抑制剂或TNF-α抑制剂疗法不敏感或不耐受的中重度CD成年患者, 与安慰剂相比upadacitinib表现出显著性的疗效, 且其治疗CD的安全属性与该药治疗类风湿性关节炎相关临床中的安全属性一致。目前, upadacitinib同时还在招募和进行多个CD、UC、类风湿性关节炎、特应性皮炎、强直性脊椎炎的Ⅱ、Ⅲ期临床试验。Peficitinib (ASP015K, JNJ-54781532)是JAK3的选择性抑制剂, 已经完成了一项UC的Ⅱ期临床试验, 但是没有继续进行后续的Ⅲ期临床研究, 目前正由Astellas公司推进其在类风湿性关节炎的Ⅲ期临床研究[53]。Filgotinib (GLPG0634)是JAK1的选择性抑制剂[54], 已经完成了一项针对中重度CD的Ⅱ期临床试验, 与安慰剂相比filgotinib表现出显著性的病情缓解, 并且其产生的不良反应也被认为在可接受范围内[55]。目前正由Galapagos公司与吉利德公司合作开展CD、UC、类风湿性关节炎等疾病的Ⅱ、Ⅲ期临床实验。PF- 06651600和PF-06700841是辉瑞在托法替布的基础上研发的, 都刚刚进入UC和CD的Ⅱ期临床研究, 其中PF-06651600是JAK3的选择性抑制剂[56], PF- 06700841是TYK2/JAK1的选择性抑制剂[57, 58]。对于只选择性抑制TYK2的化合物也有处于早期临床前研究的报道(化合物6, 图 3), 希望能够取得比JAK1-3选择性抑制剂更好的临床安全性[59, 60]。

2.5 RIP1抑制剂RIP1是受体丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶的一种, 在TNF等诱导的细胞死亡和促炎因子产生的信号通路上起关键作用。GSK2982772 (图 3)是2017年葛兰素史克报道的RIP1选择性抑制剂, 在小鼠炎症模型上表现出显著的缓解效果, 目前正在进行CD的Ⅱ期临床试验[61]。

2.6 p38 MAPK抑制剂p38 MAPK也是丝/苏氨酸蛋白激酶的一种, 其受激活化后, 可以诱导表达如TNF-α、IL-1β等多种促炎因子。但由于p38 MAPK在全身不同系统中都有表达, 对其长期抑制可能导致不良反应的发生。2014年, Hasumi等[62]报道了p38α亚型的MAPK选择性抑制剂AKP-001 (图 3), 在小鼠和大鼠的IBD模型上都有显著的缓解效果, 而且其在代谢上具有软药的特性, 被认为有益于避免全身性不良反应。

2.7 IKK2抑制剂NF-κB家族是可以调节众多蛋白表达的转录因子, 特别是促炎因子的表达。正常情况下, NF-κB与IκB抑制蛋白以一种复合物的形式在细胞质中存在, 不具有转录活性。炎症环境下, IκB激酶(IKK)被活化, 促进催化IκB的磷酸化和降解, 从而释放激活NF-κB, 进而促进促炎因子的表达。IKK包括IKK1、IKK2、IKKβ三种激酶。其中IKK2主要由炎症信号激活。因此, IKK2的抑制剂可能抑制促炎因子的表达。2012年, Watterson等[63]报道了一种新型IKK2选择性抑制剂7 (图 3), 具有良好的物理化学和药代动力学性质, 并能够在IBD小鼠模型上表现出显著的缓解效果。

2.8 Nrf2激动剂炎性小体是蛋白寡聚体, 在受到炎性刺激后, 可以促使促炎因子IL-1β、IL-18等的成熟, 从而引发后续的一系列的炎症反应。激活Nrf2有助于减少病灶周围的ROS, 进而抑制NLRP3炎性小体的活化, 缓解炎症的症状[64]。尤启冬课题组发现小分子化合物8[65-67]和9[68, 69] (图 3)都可以激活Nrf2, 并且在小鼠IBD模型上表现出显著缓解效果。

2.9 LANCL2激动剂LANCL2 (Lanthionine synthetase C-like 2)是非跨膜的蛋白受体, 其引发的信号通路与抗炎因子/促炎因子平衡密切相关。小分子化合物BT-11[70] (图 3)被报道可以与LANCL2结合, 从而活化其下游信号通路, 进而提高抗炎因子IL-10水平, 同时抑制促炎因子MCP-1和TNF-α。BT-11在小鼠IBD模型上表现出显著缓解效果, 目前正由Landos Biopharma公司申报CD的临床研究[71]。

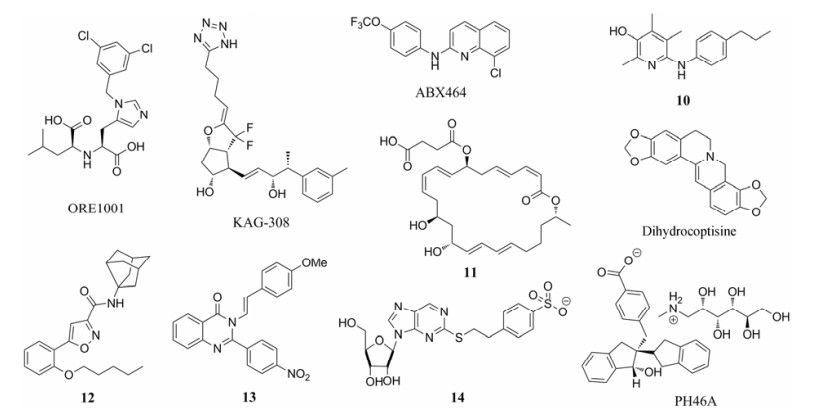

3 其他小分子免疫抑制剂IBD新药研究进展在上述两大类研究方向以外, 还有一些小分子化合物也被用于IBD的新药研发(图 4), 但都或多或少还处于作用机制方面不完全明确的阶段。ORE1001 (GL1001, MLN4760)是血管紧张素转化酶2 (ACE2)抑制剂[72], clinicaltrials.gov检索显示早已进入了轻中度UC的Ⅰ/Ⅱ期临床试验(NCT01039597, 2009年开始), 但文献中没有其抑制靶点与UC症状间关联的具体分子机制的报道[73], 而其Ⅱ期临床状态也检索显示为“未知” (unknown status)。KAG-308是前列腺素E2的受体EP4的激动剂, 被报道体外细胞实验可以抑制LPS诱导的TNF-α, 并且在IBD小鼠模型上显示出肠黏膜愈合效果(无具体机制报道)[74]。目前正由Kaken制药公司在日本开展UC的Ⅱ期临床试验。ABX464是ABIVAX公司开发的处于Ⅱ期临床阶段的抗HIV病毒的药物, 具有调节RNA合成等作用[75], 近期发现其还可以诱导巨噬细胞中的抗炎因子IL-22的过量表达, 并且在小鼠IBD模型上表现出显著的缓解效果[76], 目前己经开始了UC的Ⅱ期临床试验。

|

Figure 4 Other small molecule IBD immunosuppressants |

其他在早期研发阶段的小分子化合物, 如血管生成抑制剂10[77]、与雷帕霉素结构类似的大环内酯11[78]、转录因子xpb1激动剂二氢黄连碱及其衍生物[79-83]、内源性大麻素CB2受体激动剂12及其类似物[84]、磷脂酶A2 (PLA2)抑制剂13及其类似物[85]、A2A型腺苷受体(A2AAR)激动剂14[86], 也都有报道在小鼠或大鼠IBD模型上表现出对溃疡的显著性缓解效果。另外, 还有没有明确靶标报道的化合物PH46A在IL-10敲除的小鼠炎症模型和DSS诱导的小鼠急性IBD模型上都表现出显著的缓解效果[87]。

4 总结与展望IBD作为一种慢性复发性的消化系统常见疾病, 目前病因尚不明确, 也没有可以根治的药物。尽管抗体药物的兴起在IBD治疗上取得了很大成功, 但是由于其存在的诸多问题, 开发小分子IBD药物也就成为了患者、医生、医药企业、科研工作者共同关注的问题, 但是近20年来尚未有新的小分子IBD药物上市。本文总结了近年来小分子免疫抑制剂在IBD治疗药研发方面的进展。

除了上文提到的例子以外, 还有从其他各种角度入手开发IBD治疗药的报道[88]。如从研究IBD的病因出发通过大样本精细化定位IBD相关的基因位点[89], 针对CD的可能病因之一的副结核分枝杆菌而开发的RHB-104抗生素联合疗法[90], 针对肠黏膜屏障功能障碍而开发的LT-02卵磷脂[91], 分子量介于小分子和抗体药物之间的反义寡核苷酸类化合物GED- 0301 (mongersen)[92]、cobitolimod (kappaproct)[93]、TOP1288[94]和口服多肽PTG-100、PTG-200[95], 以及以炎症消退机制为出发点的消退素治疗IBD的研究[96]。5-ASA的类似物GED-0507-34-Levo[97]和衍生物dersalazine sodium (UR-12746)[98]也都进行了UC的Ⅱ期临床试验。另外, 传统中药、益生菌、干细胞注射等疗法也在IBD治疗上进行了有益尝试[99, 100]。

很多已经上市的其他疾病的药物(特别是作用于免疫系统的药物), 考虑到与IBD发病机制的相似点也被积极地用于IBD适应证的临床研究, 如抗真菌药氟康唑及克霉唑、抗溃疡药洛派丁胺、麻风病药物沙利度胺、皮肤T细胞淋巴瘤药物伏立诺他、银屑病药物阿普斯特、以及前文提到的托法替布等。而很多目前在研的自身免疫性疾病药物也往往同时进行着包括IBD在内的多个不同病种的临床实验研究, 如upadacitinib、马赛替尼(masitinib)、SRT2104[101]等。

从本文所举的实例来看, 当前小分子IBD新药的研发具有以下的特点和问题: ①抗体药物的成功为小分子药物的研发提供了有效靶点的参考, 如整合素、TNF-α等靶点和相关机制都成为了小分子IBD药物研发的热点, 但由于生物大分子和小分子的特点不同, 在这些靶点上, 目前小分子并没有形成突破的趋势。②对于其他自身免疫性疾病有治疗效果的药物和靶点, 也往往成为IBD药物研究的重要参考, 但可能是由于不同自身免疫性疾病间的差异, 除单抗以外, 目前尚未有一个上市的自身免疫性小分子药物被批准用于IBD。检索可见很多的小分子免疫抑制剂的适应证开发具有一定的盲目性, 常常对包括IBD在内的几种甚至十几种自身免疫性疾病都开展临床研究。如诺华的索曲妥林[102] (sotrastaurin, protein kinase C抑制剂, 抑制炎症因子的生成, 曾首先用于肾移植术后研究等)和葛兰素史克的elubrixin[103] (SB-656933, CXCR2抑制剂, 抑制趋化和血管生成, 曾首先用于治疗囊肿性纤维化研究), 这两个化合物的Ⅱ期IBD临床都早已结束, 但试验结果一直都没有公开, 也没有开展后续进一步试验的报道, 推测是没有取得成功。

IBD小分子新药的研发尽管有上述的一些问题, 但确实是正在向成功迈进。从文中实例可见其发展趋势之一就是正逐渐重视靶点的选择性, 包括靶点蛋白的亚型选择性抑制剂开发(如JAK抑制剂)、针对肠道特异性靶点的开发(如CCR9抑制剂), 以及针对UC和CD的不同点分别进行新药开发, 这都有助于避免药物分子可能的不良反应, 符合精准医学的要求。可以预期在不久的将来就会有成功的口服小分子药物被开发出来, 造福于IBD患者。

| [1] | Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease:cause and immunobiology[J]. Lancet, 2007, 369: 1627–1640. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8 |

| [2] | Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century:a systematic review of population-based studies[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390: 2769–2778. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0 |

| [3] | Qian JM, Yang H. History, current situation and progress of inflammatory bowel disease in China[J]. Chin J Pract Intern Med (中国实用内科学杂志), 2015, 35: 727–730. |

| [4] | Allen PB, Gower-Rousseau C, Danese S, et al. Preventing disability in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Ther Adv Gastroenterol, 2017, 10: 865–876. DOI:10.1177/1756283X17732720 |

| [5] | Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 365: 1713–1725. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1102942 |

| [6] | Cheifetz AS. Management of active Crohn disease[J]. JAMA, 2013, 309: 2150–2158. DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.4466 |

| [7] | Ananthakrishnan AN, Bernstein CN, Iliopoulos D, et al. Envi ronmental triggers in IBD:a review of progress and evidence[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 15: 39–49. |

| [8] | Kondamudin PK, Malayandi R, Eaga C, et al. Drugs as causative agents and therapeutic agents in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2013, 3: 289–296. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2013.06.004 |

| [9] | Amiot A, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Current, new and future bio logical agents on the horizon for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Ther Adv Gastroenterol, 2015, 8: 66–82. DOI:10.1177/1756283X14558193 |

| [10] | Zhao CX, Hu ZW, Cui B. Recent advances in monoclonal antibody-based therapeutics[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2017, 52: 837–847. |

| [11] | Nielsen OH, Seidelin JB, Ainsworth M, et al. Will novel oral formulations change the management of inflammatory bowel disease?[J]. Expert Opin Invest Drugs, 2016, 25: 709–718. DOI:10.1517/13543784.2016.1165204 |

| [12] | Zhou Y, Shen J, Ran ZH. Advances in study on novel oral biological agents in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Chin J Gastroenterol (胃肠病学), 2017, 22: 498–501. |

| [13] | Villablanca EJ, Cassani B, von Andrian UH, et al. Blocking lymphocyte localization to the gastrointestinal mucosa as a therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 140: 1776–1784. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.015 |

| [14] | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Christopher R, Behan D, et al. Modulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Autoimmun Rev, 2017, 16: 495–503. DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.03.007 |

| [15] | Mi JQ, Zhao MM, Yang S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of H002, a novel S1PR1 modulator, and its metabolites in rat blood using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2016, 6: 576–583. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.06.001 |

| [16] | Zhou WQ, Zhang HJ, Jin J, et al. Immunosuppressive effect of S1P1 receptor agonist FTY720[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2012, 47: 546–550. |

| [17] | Song J, Matsuda C, Kai Y, et al. A novel sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist, 2-amino-2-propanediol hydro chloride (KRP-203), regulates chronic colitis in interleukin-10 gene-deficient mice[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2008, 324: 276–283. |

| [18] | Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Safety and efficacy of amiselimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (MOMENTUM):a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2016, 15: 1148–1159. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30192-2 |

| [19] | Scott FL, Clemons B, Brooks J, et al. Ozanimod (RPC1063) is a potent sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1(S1P1) and receptor-5(S1P5) agonist with autoimmune disease modifying activity[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2016, 173: 1778–1792. DOI:10.1111/bph.v173.11 |

| [20] | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Wolf DC, et al. Ozanimod induc tion and maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 374: 1754–1762. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1513248 |

| [21] | Buzard DJ, Kim SK, Lopez L, et al. Discovery of APD334:design of a clinical stage functional antagonist of the sphin gosine-1-phosphate-1 receptor[J]. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2014, 5: 1313–1317. DOI:10.1021/ml500389m |

| [22] | Dinges J, Harris CM, Wallace GA, et al. Hit-to-lead evaluation of a novel class of sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase inhibitors[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2016, 26: 2297–2302. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.043 |

| [23] | Pizzonero M, Dupont S, Babel M, et al. Discovery and optimization of an azetidine chemical series as a free fatty acid receptor 2(FFA2) antagonist:from hit to clinic[J]. J Med Chem, 2014, 57: 10044–10057. DOI:10.1021/jm5012885 |

| [24] | Vermeire S, Kojeck V, Knoflícek V, et al. GLPG0974, an FFA2 antagonist, in ulcerative colitis:efficacy and safety in a multicenter proof-of-concept study[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2015, 9: S39. |

| [25] | Galapagos press release: Galapagos reports results with GLPG1205 in ulcerative colitis[EB/OL]. Mechelen, Belgium: Galapagos NV, January 26, 2016[2018-01-30]. http://www.glpg.com/docs/view/56a70f4ad23cf-en. |

| [26] | Sugiura T, Kageyama S, Andou A, et al. Oral treatment with a novel small molecule alpha 4 integrin antagonist, AJM300, prevents the development of experimental colitis in mice[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2013, 7: e533–e542. DOI:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.03.014 |

| [27] | Yoshimura N, Watanabe M, Motoya S, et al. Safety and efficacy of AJM300, an oral antagonist of 4 integrin, in induction therapy for patients with active ulcerative colitis[J]. Gastro enterology, 2015, 149: 1775–1783. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.044 |

| [28] | Takazoe M, Watanabe M, Kawaguchi T, et al. Oral alpha-4 integrin inhibitor (AJM300) in patients with active Crohn's disease - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 136: A181. |

| [29] | Semko CM, Chen L, Dressen DB, et al. Discovery of a potent, orally bioavailable pyrimidine VLA-4 antagonist effective in a sheep asthma model[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2011, 21: 1741–1743. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.075 |

| [30] | Xu YZ, Konradi WA, Bard F, et al. Arylsulfonamide pyrimidines as VLA-4 antagonists[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2013, 23: 3070–3074. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.010 |

| [31] | Xu YZ, Smith JL, Semko CM, et al. Orally available and efficacious α4β1/α4β7 integrin inhibitors[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2013, 23: 4370–4373. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.076 |

| [32] | Papst S, Noisier AFM, Brimble MA, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of tyrosine modified analogues of α4β7 integrin inhibitor biotin-R8ERY[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2012, 20: 5139–5149. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.07.010 |

| [33] | Wendt E, Keshav S. CCR9 antagonism:potential in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Clin Exp Gastroenterol, 2015, 8: 119–130. |

| [34] | Walters MJ, Wang Y, Lai N, et al. Charaterization of CCX282-B, an orally bioavailable antagonist of the CCR9 chemokine receptor, for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2010, 335: 61–69. DOI:10.1124/jpet.110.169714 |

| [35] | Keshav S, Vaňásek T, Niv Y, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of CCX282-B, an orally- administered blocker of chemokine receptor CCR9, for patients with Crohn's disease[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8: e60094. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0060094 |

| [36] | Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, et al. Randomised clinical trial:vercirnon, an oral CCR9 antagonist, vs. placebo as induction therapy in active Crohn's disease[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2015, 42: 1170–1181. DOI:10.1111/apt.2015.42.issue-10 |

| [37] | Kalindjian SB, Kadnur SV, Hewson CA, et al. A new series of orally bioavailable chemokine receptor 9(CCR9) antagonists; possible agents for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease[J]. J Med Chem, 2016, 59: 3098–3111. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01840 |

| [38] | Zhang J, Romero J, Chan A, et al. Biarylsulfonamide CCR9 inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2015, 25: 3661–3664. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.06.046 |

| [39] | Pandya BA, Baber C, Chan A, et al. Discovery of indole inhibitors of chemokine receptor 9(CCR9)[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2016, 26: 3322–3325. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.05.043 |

| [40] | Cohen BL, Sachar DB. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and other new drugs for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. BMJ, 2017, 357: j2505. |

| [41] | Park SY, Ku SK, Lee ES, et al. 1, 3-Diphenylpropenone ameliorates TNBS-induced rat colitis through suppression of NF-κB activation and IL-8 induction[J]. Chem Biol Interact, 2012, 196: 39–49. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2012.02.002 |

| [42] | Kadayat TM, Banskota S, Gurung P, et al. Discovery and structure-activity relationship of 2-benzylidene-2, 3-dihydro-1H- inden-1-oneand benzofuran-3(2H)-one derivatives as a novel class of potential therapeutics for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2017, 137: 575–597. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.018 |

| [43] | Hayakawa N, Noguchi M, Takeshita S, et al. Structure- activity relationship study, target identification, and pharma cological characterization of a small molecular IL-12/23 inhibitor, APY0201[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2014, 22: 3012–3029. |

| [44] | Mendel I, Shoham A, Propheta-Meiran O, et al. A lecinoxoid, an oxidized phospholipid small molecule, constrains CNS autoimmune disease[J]. J Neuroimmunol, 2010, 226: 126–135. DOI:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.06.011 |

| [45] | Mendel I, Feige E, Yacov N, et al. VB-201, an oxidized phospholipid small molecule, inhibits CD14- and Toll-like receptor-2-dependent innate cell activation and constrains atherosclerosis[J]. Clin Exp Immunol, 2013, 175: 126–137. |

| [46] | Feige E, Yacov N, Salem Y, et al. Inhibition of monocyte chemotaxis by VB-201, a small molecule lecinoxoid, hinders atherosclerosis development in ApoE-/- mice[J]. Athero sclerosis, 2013, 229: 430–439. DOI:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.06.005 |

| [47] | Mendel I, Yacov N, Salem S, et al. Identification of motile sperm domain-containing protein 2 as regulator of human monocyte migration[J]. J Immunol, 2017, 198: 2125–2132. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1601662 |

| [48] | Banerjee S, Biehl A, Gadina M, et al. JAK-STAT signaling as a target for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases:current and future prospects[J]. Drugs, 2017, 77: 521–546. DOI:10.1007/s40265-017-0701-9 |

| [49] | Yin Y, Zhang TT, Zhang DY. Research progress of JAK-3 kinase and its inhibitors[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2016, 51: 1520–1529. |

| [50] | Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 376: 1723–1736. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1606910 |

| [51] | Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al. A phase 2 study of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with Crohn's disease[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 12: 1485–1493. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.01.029 |

| [52] | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Panes J, et al. Safety and efficacy of ABT-494(upadacitinib), an oral JAK1 inhibitor, as induction therapy in patients with Crohn's disease:results from CELEST[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152: S1308–S1309. |

| [53] | Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Iwasaki M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor peficitinib (ASP015K) monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in Japan:a 12-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase Ⅱb study[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2016, 75: 1057–1064. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208279 |

| [54] | Menet CJ, Fletcher SR, Lommen GV, et al. Triazolopyridines as selective JAK1 inhibitors:from hit identification to GLP0634[J]. J Med Chem, 2014, 57: 9323–9342. DOI:10.1021/jm501262q |

| [55] | Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study):results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389: 266–275. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32537-5 |

| [56] | Telliez JB, Dowty ME, Wang L, et al. Discovery of a JAK3-selective inhibitor:functional differentiation of JAK3- selective inhibition over pan-JAK or JAK1-selective inhibition[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2016, 11: 3442–3451. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.6b00677 |

| [57] | Fensome A, Gopalsamy A, Gerstenberger BS, et al. Preparation of aminopyrimidinyl derivatives as inhibitors of JAK kinases useful in therapy of diseases: WO, 2016027195[P]. 2016-02- 25. |

| [58] | Banfield C, Scaramozza M, Zhang W, et al. The safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of a TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor (PF-06700841) in healthy subjects and patients with plaque psoriasis[J]. J Clin Pharmacol, 2018, 58: 434–447. DOI:10.1002/jcph.v58.4 |

| [59] | Liang J, Tsui V, van Abbema A, et al. Lead identification of novel and selective TYK2 inhibitors[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2013, 67: 175–187. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.070 |

| [60] | Liang J, van Abbema A, Balazs M, et al. Lead optimization of a 4-aminopyridine benzamide scaffold to identify potent, selective, and orally bioavailable TYK2 inhibitors[J]. J Med Chem, 2013, 56: 4521–4536. DOI:10.1021/jm400266t |

| [61] | Harris PA, Berger SB, Jeong JU, et al. Discovery of a first-in-class receptor interacting protein 1(RIP1) kinase specific clinical candidate (GSK2982772) for the treatment of inflammatory diseases[J]. J Med Chem, 2017, 60: 1247–1261. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01751 |

| [62] | Hasumi K, Sato S, Saito T, et al. Design and synthesis of 5-[(2-chloro-6-fluorophenyl)acetylamino]-3-(4-fluorophenyl)-4- (4-pyrimidinyl)isoxazole (AKP-001), a novel inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase with reduced side effects based on the antedrug concept[J]. Bioorg Med Chem, 2014, 22: 4162–4176. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2014.05.045 |

| [63] | Watterson SH, Langevine CM, Kirk KV, et al. Novel tricyclic inhibitors of IKK2:discovery and SAR leading to the identify cation of 2-methoxy-N-((6-(1-methyl-4-(methylamino)-1, 6- dihydroimidazo[4, 5-d]pyrrolo[2, 3-b]pyridine-7-yl)pyridine-2- yl)methyl) acetamide (BMS-066)[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2011, 21: 7006–7012. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.111 |

| [64] | Lu MC, Ji JA, Jiang ZY, et al. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target:an update[J]. Med Res Rev, 2016, 36: 924–963. DOI:10.1002/med.21396 |

| [65] | Jiang ZY, Lu MC, Xu LL, et al. Discovery of potent Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction inhibitor based on molecular binding determinants analysis[J]. J Med Chem, 2014, 57: 2736–2745. DOI:10.1021/jm5000529 |

| [66] | Jiang ZY, Xu LL, Lu MC, et al. Structure-activity and structure-property relationship and exploratory in vivo evalua tion of the nanomolar Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction inhibitor[J]. J Med Chem, 2015, 58: 6410–6421. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00185 |

| [67] | Lu MC, Ji JA, Jiang YL, et al. An inhibitor of the Keap1- Nrf2 protein-protein interaction protects NCM460 colonic cells and alleviates experimental colitis[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 26585. DOI:10.1038/srep26585 |

| [68] | Xi MY, Jia JM, Sun HP, et al. 3-Aroylmethylene-2, 3, 6, 7- tetrahydro-1H-pyrazino[2, 1-a]isoquinolin-4(11bH)-ones as potent Nrf2/ARE inducers in human cancer cells and AOM- DSS treated mice[J]. J Med Chem, 2013, 56: 7925–7938. DOI:10.1021/jm400944k |

| [69] | Wang Y, Wang H, Qian C, et al. 3-(2-Oxo-2-phenyle thylidene)-2, 3, 6, 7-tetrahydro-1H-pyrazino[2, 1-a] isoquinolin- 4(11bH)-one (compound 1), a novel potent Nrf2/ARE inducer, protects against DSS-induced colitis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2016, 101: 71–86. DOI:10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.015 |

| [70] | Carbo A, Gandour RD, Hontecillas R, et al. An N, N-bis(ben zimidazolylpicolinoyl)piperazine (BT-11):a novel lanthionine synthetase C-like 2-based therapeutic for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. J Med Chem, 2016, 59: 10113–10126. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00412 |

| [71] | Landos Biopharma: expansible therapeutic pipeline[EB/OL]. Blacksburg, VA, USA: Landos Biopharma, 2017[2018-01-30]. https://landosbiopharma.com/products. |

| [72] | Dales NA, Gould AE, Brown JA, et al. Substrate-based design of the first class of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) inhibitors[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2002, 124: 11852–11853. DOI:10.1021/ja0277226 |

| [73] | Byrnes JJ, Gross S, Ellard C, et al. Effects of the ACE2 inhibitor GL1001 on acute dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice[J]. Inflamm Res, 2009, 58: 819–827. DOI:10.1007/s00011-009-0053-3 |

| [74] | Watanabe Y, Murata T, Amakawa M, et al. KAG-308, a newly- identified EP4-selective agonist shows efficacy for treating ulcerative colitis and can bring about lower risk of colorectal carcinogenesis by oral administration[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2015, 754: 179–189. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.021 |

| [75] | Campos N, Myburgh R, Garcel A, et al. Long lasting control of viral rebound with a new drug ABX464 targeting Rev - mediated viral RNA biogenesis[J]. Retrovirology, 2015, 12: 30. DOI:10.1186/s12977-015-0159-3 |

| [76] | Chebli K, Papon L, Paul C, et al. The anti-HIV candidate Abx464 dampens intestinal inflammation by triggering Il-22 production in activated macrophages[J]. Sci Rep, 2011, 7: 4860. |

| [77] | Banskota S, Kang H, Kim DG, et al. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory activity of 6-amino-2, 4, 5-trimethylpyridin-3-ols against inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2016, 26: 4587–4591. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.08.075 |

| [78] | Park S, Regmi SC, Park SY, et al. Protective effect of 7-O-succinyl macrolactin A against intestinal inflammation is mediated through PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR and NF-κB signaling pathways[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2014, 735: 184–192. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.04.024 |

| [79] | Zhang ZH, Zhang HJ, Deng AJ, et al. Synthesis and structure- activity relationships of quaternary coptisine derivatives as potential anti-ulcerative colitis agents[J]. J Med Chem, 2015, 58: 7557–7571. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00964 |

| [80] | Zhang ZH, Wu LQ, Deng AJ, et al. New synthetic method of 8-oxocoptisine starting from natural quaternary coptisine as antiulcerative colitis agent[J]. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2014, 16: 841–846. DOI:10.1080/10286020.2014.932778 |

| [81] | Ren J, Wang YG, Wang AG, et al. Cembranoids from the gum resin of Boswellia carterii as potential antiulcerative colitis agents[J]. J Nat Prod, 2015, 78: 2322–2331. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00104 |

| [82] | Xie M, Zhang HJ, Deng AJ, et al. Synthesis and structure- activity relationships of N-dihydrocoptisine-8-ylidene aromatic amines and N-dihydrocoptisine-8-ylidene aliphatic amides as antiulcerative colitis agents targeting XBP1[J]. J Nat Prod, 2016, 79: 775–783. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00807 |

| [83] | Zhang ZH, Li J, Zhang HJ, et al. Versatile methods for synthesizing organic acid salts of quaternary berberine-type alkaloids as anti-ulcerative colitis agents[J]. J Asian Nat Prod Res, 2016, 18: 576–589. DOI:10.1080/10286020.2016.1171760 |

| [84] | Tourteau A, Andrzejak V, Body-Malapel M, et al. 3- Carboxamido-5-aryl-isoxazoles as new CB2 agonists for the treatment of colitis[J]. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2013, 21: 5384–5394. |

| [85] | Alafeefy AM, Awaad AS, Abdel-Aziz HA, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of certain 3-substituted benzylideneamino- 2-(4-nitrophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives[J]. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem, 2015, 30: 270–276. DOI:10.3109/14756366.2014.915398 |

| [86] | El-Tayeb A, Michael S, Abdelrahman A, et al. Development of polar adenosine A2A receptor agonists for inflammatory bowel disease:synergism with A2B antagonists[J]. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2011, 2: 890–895. DOI:10.1021/ml200189u |

| [87] | Frankish N, Sheridan H. 6-(Methylamino)hexane-1, 2, 3, 4, 5-pentanol 4-(((1S, 2S)-1-hydroxy-2, 3-dihydro-1H, 1'H-[J]. J Med Chem, 2012, 55: 5497–5505. DOI:10.1021/jm300390f |

| [88] | Torres J, Danese S, Colombel JF. New therapeutic avenues in ulcerative colitis:thinking out of the box[J]. Gut, 2013, 62: 1642–1652. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303959 |

| [89] | Huang H, Fang M, Jostins L, et al. Fine-mapping inflammatory bowel disease loci to single-variant resolution[J]. Nature, 2017, 547: 173–178. DOI:10.1038/nature22969 |

| [90] | Alcedo KP, Thanigachalam S, Naser SA. RHB-104 triple antibiotics combination in culture is bactericidal and should be effective for treatment of Crohn's disease associated with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis[J]. Gut Pathog, 2016, 8: 32. DOI:10.1186/s13099-016-0115-3 |

| [91] | Karner K, Kocjan A, Stein J, et al. First multicenter study of modified release phosphatidylcholine "LT-02" in ulcerative colitis:a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in mesalazine- refractory courses[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2014, 109: 1041–1051. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2014.104 |

| [92] | Monteleone G, Sabatino AD, Ardizzone S, et al. Impact of patient characteristics on the clinical efficacy of mongersen (GED-0301), an oral Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide, in active Crohn's disease[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2016, 43: 717–724. DOI:10.1111/apt.2016.43.issue-6 |

| [93] | Kuznetsov NV, Zargari A, Gielen AW, et al. Biomarkers can predict potential clinical responders to DIMS0150 a toll-like receptor 9 agonist in ulcerative colitis patients[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2014, 14: 79. DOI:10.1186/1471-230X-14-79 |

| [94] | Solanke Y, Foster M, Fyfe MC, et al. The narrow spectrum kinase inhibitor (NSKI) TOP1288 demonstrates potent anti- inflammatory effects in a T cell adoptive transfer colitis model through a topical mode of action[J]. Gastroenterology, 2017, 152: S31. |

| [95] | Protagonist therapeutics pipline[EB/OL]. Newark, CA, USA: Protagonist therapeutics, January 26, 2017[2018-01-30]. http://www.protagonist-inc.com/randd-pipeline.php#ptg100. |

| [96] | Lee CH. Resolvins as new fascinating drug candidates for inflammatory diseases[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 2012, 35: 3–7. DOI:10.1007/s12272-012-0121-z |

| [97] | Speca S, Rousseaux C, Dubuquoy C, et al. Novel PPARγ modulator GED-0507-34 Levo ameliorates inflammation- driven intestinal fibrosis[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2016, 22: 279–292. DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000618 |

| [98] | Pontes C, Vives R, Torres F, et al. Safety and activity of dersalazine sodium in patients with mild-to-moderate active colitis:double-blind randomized proof of concept study[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2014, 20: 2004–2012. DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000166 |

| [99] | Chen F, Yan CK. Recent progress in drug therapy of ulcerative colitis[J]. World Chin J Digestol (世界华人消化杂志), 2016, 24: 1840–1845. DOI:10.11569/wcjd.v24.i12.1840 |

| [100] | Wang FD, Wang YL, Wang YW, et al. Effect of Huangqin Tang on the function of regulatory TLR4/MyD88 signal pathway in rats with ulcerative colitis[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2016, 51: 1558–1563. |

| [101] | Hoffmann E, Wald J, Lavu S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of SRT2104, a first-in-class small molecule activator of SIRT1, after single and repeated oral administration in man[J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2012, 75: 186–196. |

| [102] | Pascher1 A, Simone De P, Pratschke J, et al. Protein kinase C inhibitor sotrastaurin in de novo liver transplant recipients:a randomized phase Ⅱ trial[J]. Am J Transpl, 2015, 15: 1283–1292. DOI:10.1111/ajt.13175 |

| [103] | Moss RB, Mistry SJ, Konstan MW, et al. Safety and early treatment effects of the CXCR2 antagonist SB-656933 in patients with cystic fibrosis[J]. J Cyst Fibros, 2013, 12: 241–248. DOI:10.1016/j.jcf.2012.08.016 |

2018, Vol. 53

2018, Vol. 53