2. 天津中医药大学 第一附属医院, 天津 300193

2. The First Affiliated Hospital, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 300193, China

传统中医药具有完整的理论体系、独特的诊疗方式及良好的临床疗效, 长期为祖国人民的健康保驾护航, 但其制剂品种相对单一, 多以汤、丸和散剂为主, 因其存在有效成分溶解度不高、生物利用度低等问题, 限制了中医药走向世界的速度与进程, 因此寻找更加有效的、现代化的中药制备工艺与给药方式是实现中医药现代化大跨步的重要途径。随着现代医学的发展, 众多纳米级的载药材料被人们发现或研发, 其所具有的特定靶向性、稳定性等诸多优势, 逐渐被人们所重视[1]。近年来, 随着对细胞微观环境的进一步研究, 发现了新型的以外泌体(exosomes)所主导的细胞间信息沟通方式, 并发现其具有所包裹遗传信息物质脂质膜结构的稳固性、体液中分布的广泛性和易于获得性等药物载体的基本特征, 因此外泌体作为一种潜在的药物载体备受关注。Alvarez-erviti等[2]首次利用骨髓源树突状细胞作为外泌体的来源运送siRNA, 并穿过血脑屏障到达中枢神经系统, 验证了外泌体作为药物载体的可行性。本文就外泌体作为中药载体的最新研究进行综述, 旨在为中医药的进一步发展提供参考。

1 外泌体的形成与特征外泌体是在环境刺激或细胞活化时, 释放到细胞外的一种纳米级囊泡[3]。根据囊泡结构的直径大小将其分为3类:外泌体(直径40~100 nm)、微泡(microvesicles, 直径100~1 000 nm)和凋亡小体(apoptotic body, 直径1~4 μm)[4]。外泌体的形成是通过细胞内吞途径, 将胞质中的蛋白质、DNA片段及miRNA等物质聚集在多囊泡胞内体, 再经过多囊泡与质膜的融合、裂解释放至细胞外, 形成外泌体[5]。外泌体的内部结构主要取决于其来源细胞, 但多数外泌体均富含整合素、热休克蛋白、四跨膜蛋白超家族(CD9、CD63、CD81和CD82)、细胞内源性蛋白alix和Rab蛋白家族, 这些蛋白可作为鉴别外泌体的可靠标志物[6]。

外泌体所携带的内容物具有特异性, 主要反映来源细胞的特性与生理病理变化[7]。例如, 在前列腺癌患者血清内发现, 具有肿瘤转移灶的患者血清外泌体中miRNA-141的表达水平特异性升高[8]。目前已证实, 外泌体主要通过“穿梭RNA”[9]或转运蛋白[10]发挥重要作用。通过“穿梭RNA”信号分子, 能直接传达母细胞的遗传信息, 调节受体细胞功能。例如, 子宫内膜间充质干细胞来源的外泌体在与缺氧/复氧心肌细胞共培养下能更多地富集miR-21并递送至心肌细胞中, miR-21通过调控PTEN/Akt信号通路减少心肌细胞凋亡, 从而发挥保护心肌的作用[11]。

2 外泌体作为药物载体的特点随着化学药物研发难度的逐年加大, 研发周期逐渐延长, 药物本身存在诸如水溶性差、生物利用度低、体内分布不理想、对细胞靶向与渗透能力较低等问题, 使得寻找新型的药物递送系统来解决上述问题并增加药物的疗效与安全性成为必然的选择[12]。

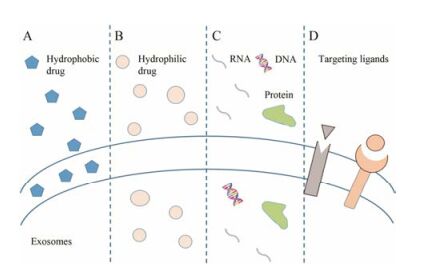

外泌体因内部含有丰富的蛋白质和核酸, 并具有稳定的细胞间靶向通讯功能, 被视为天然的纳米级药物载体而备受关注。如图 1所示, 外泌体具有稳固的双分子磷脂结构, 内部空腔有助于负载大量的水溶性物质, 而双分子磷脂中间的疏水区微相则能包裹疏水性物质[13], 这种特殊结构能保护其内容物在恶劣的胞外环境中长期存在而不被降解或稀释, 也能避免被网状内皮系统捕获和清除, 实现靶向效应[14]。同时, 其表面具有特殊的脂质结构与蛋白, 利于与受体靶细胞融合, 将内容物或药物释放入细胞内部, 实现对靶细胞的干预[13]。此外, 几乎所有细胞都能分泌外泌体, 并且广泛存在于人体的各种体液中, 这为外泌体从患者体液中收集或从自身供体细胞培养分离提供了可能性。利用自源性外泌体作为药物载体具有良好的生物相容性与非免疫原性, 能提高有效利用率, 减少药物清除率[15]。

|

Figure 1 Diagram of the different types of exosomes drug delivery systems. Exosomes are small vesicles comprised of a lipid bilayer which surround the aqueous core. A: Hydrophobic pharmaceutical compound in the bilayer; B: Hydrophilic drug compound loaded in the aqueous core; C: Exosomes can package proteins, DNA and various forms of RNA for delivery; D: The targeting ligands can be attached to exosomes surface |

目前, 对于外泌体的供体细胞研究主要集中在肿瘤细胞、间充质干细胞(mesenchymal stem cell, MSC)、免疫细胞及其他来源。肿瘤细胞来源外泌体(tumor-derived exosome, TEX)可以携带肿瘤特异性抗原、蛋白质和miRNA等物质, 从而起到抗肿瘤免疫的作用[16]。同时, TEX也存在诱导活化的T细胞凋亡、抑制单核细胞分化、产生促炎微环境等潜在缺陷[17]。MSC来源外泌体具有MSC的生物学特性, 可以调节机体免疫和促进组织修复, 并且相对于其他供体细胞, MSC生产外泌体的能力更强[18]。然而, 有研究表明MSC来源外泌体能通过ERK1/2和p38 MAPK通路激活肿瘤血管生成相关因子, 从而促进肿瘤生长[19]。与其他供体细胞相比, 免疫细胞来源的外泌体能更好地避免免疫清除, 延长外泌体在外周循环中的滞留时间, 从而提高药物的疗效[20]。因此, 临床上需要根据具体疾病类型, 选择合适的供体细胞才能规避缺陷, 发挥各细胞的优势。同时, 出于对外泌体安全性和实现大规模制备的考虑, 有学者利用葡萄、柚子等植物或牛奶作为外泌体的替代供体来源[21-23]。其中, 牛奶来源外泌体在跨物种应用中没有免疫排斥和炎症反应, 并且结构稳定、产量充足, 能提高口服生物利用度, 是外泌体较好的来源[21]。

外泌体装载药物主要通过主动和被动两种方式实现。主动载入是通过对供体细胞进行转染或将药物与供体细胞共培养, 使供体细胞分泌的外泌体包含药物[24]; 或直接通过药物与外泌体共培养, 使药物依靠浓度梯度进入外泌体中[25]。被动方式则主要有电穿孔、超声、挤压和冻融等方式[26-29]。其中, 相对于冻融与孵育, 超声和挤压能使更多的药物装载入外泌体[20]。而相对其他方式, 电穿孔因操作参数可控, 对外泌体结构损伤较小, 效率较高而成为应用较广的方式[28]。但是, 选取何种方式进行药物加载, 主要取决于药物的分子质量及亲水性或疏水性。

3 外泌体作为中药载体的研究进展外泌体作为载体可以装载不同种类的药物, 目前主要集中在miRNA和mRNA等基因类[15]、多柔比星等抗肿瘤药物[30]及增强免疫功能的特定蛋白质等[31]。而近年来随着中医药研究的深入, 以青蒿素为代表的药物有效成分逐渐被大家所认识[32]。而在精准医学的背景下, 利用外泌体等更加有效的载药方式, 实现对传统药物有效成分的精确递送, 对传统药物发挥更好的临床疗效具有深远的意义。

3.1 对负载中药单体外泌体的研究 3.1.1 姜黄素姜黄素(curcumin)是姜黄类植物中含有的一种多元酚, 它具有抗炎、抗氧化应激及抑制恶性肿瘤细胞增殖等广泛的药理作用[33]。但在临床应用中, 其水溶性较差, 有效成分利用率偏低[34]。研究发现, 利用外泌体作为姜黄素的药物载体, 姜黄素在体内的浓度、药物稳定性随之增加, 提高了药物疗效并且没有明显的不良反应[35]。

在体外研究中, 利用肠道Caco-2细胞模型模拟人体消化过程, 发现利用牛奶来源外泌体作为姜黄素载体, 可以明显提高其溶解度, 增加肠道细胞摄取率, 进而降低因消化过程造成的有效成分的降解, 提高生物利用度。牛奶来源的外泌体中包含miR-21的识别蛋白, 已有研究证实姜黄素能通过抑制肿瘤细胞中miR-21的表达, 促进miR-21经外泌体排出胞外, 进而抑制肿瘤细胞的增殖和迁移[36], 说明姜黄素装载在牛奶来源的外泌体能经口服方式有效地调控靶细胞[25]。进一步研究显示, 姜黄素可改变慢性粒细胞性白血病外泌体的构成, 使其富集细胞穿梭miR-21与抗血管生成蛋白, 通过调控miR-21的表达, 下调人脐静脉内皮细胞中IL-8、同源物基因家族成员B和血管细胞黏附分子-1的表达水平, 维持内皮屏障功能的稳定, 抑制内皮细胞的迁移与黏附, 起到抗血管新生的作用[37]。负载姜黄素的外泌体(curcumin exosomes, CUR-EXO)能促进抗精神类药物作用下的细胞胆固醇外流, 减少因药物不良反应造成的细胞内脂质沉积, 维持细胞内胆固醇平衡[38]。CUR-EXO亦可经外泌体转运通过血脑屏障, 运送到脑组织中, 减轻因高同型半胱氨酸血症所造成的氧化应激, 降低基质金属蛋白酶9的表达, 恢复紧密连接蛋白Claudin-5、ZO-1的正常表达, 以此保护大脑微血管内皮细胞功能完整性, 维持脑血管屏障功能[39]。

在体内研究中, 利用鼠淋巴瘤细胞来源外泌体运载姜黄素, 干预脂多糖(LPS)引起的感染性休克小鼠模型, 结果显示CUR-EXO能显著抑制小鼠肺组织中CD11b+Gr-1+髓样免疫抑制细胞的募集, 表现出抗炎作用, 单纯使用姜黄素则对CD11b+Gr-1+细胞无明显效果。而对比姜黄素不同载体对LPS诱发小鼠感染性休克模型的治疗效果发现, 外泌体作为载体较脂质体载体治疗的小鼠存活率更高, 这可能与外泌体更易进入Gr-1+细胞相关[35]。

3.1.2 紫杉醇紫杉醇(paclitaxel, PTX)是一种天然的抗肿瘤药物, 已在临床上广泛应用, 但因其具有剂量依赖性毒性、水溶性差和静脉注射治疗效果较差等问题限制了PTX使用[40, 41]。在异种肿瘤移植的裸小鼠肺癌模型中, 使用牛奶来源的外泌体作为PTX的药物载体, 经口服给药结果显示, 负载PTX的外泌体具有良好的耐酸性和稳定性, 能明显抑制肿瘤的生长, 并且较静脉给药显著降低了药物本身毒性与免疫反应[42]。有实验利用超声引导巨噬细胞来源外泌体装载PTX, 发现外泌体载药组较传统给药方式对P-gp阳性耐药细胞的细胞毒性增加了50倍以上, 对Lewis肺癌自发转移模型具有很强的杀伤作用, 说明以外泌体为载体的PTX具有改善化疗药物耐药性, 增强抗癌效果的潜能[26]。

3.1.3 梓醇梓醇(catalpol)是地黄中主要的环烯醚萜类化合物, 具有抗氧化、抗凋亡和促神经营养因子生成等作用, 保护神经细胞的功能[43]。将负载梓醇的外泌体(catalpol exosomes, C-Exos)与人神经母细胞瘤(SH-SY5Y)细胞共培养24 h, 与模型组及空白外泌体组相比, SH-SY5Y神经细胞存活率上升17%, 证明梓醇能通过外泌体途径将有效成分运送至神经细胞中, 起到神经保护作用[44]。

3.1.4 β-榄香烯β-榄香烯(β-elemene, β-ELE)是从莪术根茎中提取的一种新型的非细胞毒性抗肿瘤药物, 具有疗效确切、低毒等特性, 能通过凋亡途径[45]抑制肝癌细胞[46]、乳腺癌细胞[47]等多种肿瘤细胞的增殖与迁移, 并能逆转肿瘤细胞的多药耐药性, 增加对化疗药物的敏感性[48], 但其作用机制尚未完全阐明。目前研究认为第10染色体同源丢失性磷酸酶-张力蛋白基因(phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten, PTEN)能抑制多种癌症的发生, 并能增加耐药细胞对药物的敏感性[49]。Zhang等[50]研究显示, 利用乳腺癌耐药细胞株与负载β-ELE的外泌体(50 μmol·L-1/L, 30 h)共培养, 分析发现负载β-ELE的外泌体上调了耐药细胞中miR-34a及其靶基因PTEN的表达, 并下调耐药miR-452和多药耐药基因蛋白P-gp的表达, 明显逆转了乳腺癌的耐药性。

3.1.5 雷公藤红素雷公藤红素(celastrol)是雷公藤中含有的一种醌甲基三萜类化合物, 具有抗炎、免疫抑制和抗肿瘤等多种作用[51]。但其水溶性差、生物利用度低和口服易产生不良反应等问题影响了临床广泛应用。利用牛奶来源外泌体作为雷公藤红素载体能有效抑制非小细胞肺癌的增殖, 并呈时间和浓度依赖性。研究发现, 载药外泌体抑制了肿瘤坏死因子α所诱导的NF-κB的活化, 并能通过内质网应激途径激活细胞凋亡, 从而抑制非小细胞肺癌的增殖与转移。同时, 通过在体实验显示, 口服载有雷公藤红素的外泌体对C57小鼠肝、肾功能没有明显影响。表明利用牛奶来源外泌体作为雷公藤红素的载体, 能明显降低药物的不良反应, 提高药物疗效[52]。

3.2 对负载中药复方制剂外泌体的研究 3.2.1 补阳还五汤补阳还五汤(Buyang Huanwu decoction, BYHWD)临床多用于中风、冠心病等心脑血管疾病, 以口服用药为主, 但有效物质吸收性较差。因此, 有研究利用大鼠MSC来源外泌体作为BYHWD有效成分的载体, 在采用线栓法建立大鼠局灶性脑缺血再灌注损伤模型中进行腹膜注射, 结果显示负载BYHWD的外泌体组能激活血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF), 上调miR-126表达, 并抑制miR-221/222表达, 促进缺血区新生血管的形成, 减轻缺血性脑损伤。其中miR-126能通过PI3K信号通路激活VEGF与成纤维细胞生长因子从而介导血管生成, 而miR-221/222具有抗血管生成的作用。说明负载BYHWD的外泌体能通过调节相应miRNAs, 促进缺血区脑血管生成, 改善缺血症状[53]。

3.2.2 通心络胶囊通心络胶囊是心脑血管病常用药, 具有益气活血, 通络止痛的功效。选择将通心络胶囊处理过的人心肌细胞(human cardiacmyocyte, HCM)与人心肌微血管内皮细胞(microvascular endothelial cells, HCMECs)缺氧/复氧模型共培养, 结果显示HCMECs的凋亡水平明显下降, 而加入外泌体抑制剂GW4869后该作用消失, 证明HCM来源外泌体可作为通心络胶囊有效成分的载体。研究者还发现通心络胶囊处理过的HCM能提高HCMECs中p70s6k1和GSK-3β的磷酸化水平, 说明通心络胶囊可能通过HCM来源的外泌体激活再灌注损伤挽救激酶通路, 进而减少HCMECs的缺氧/复氧损伤[54]。

4 展望外泌体作为细胞自身分泌的囊泡, 是细胞间信息交换的重要载体, 其在体内分布的广泛性、非免疫性与易于穿过细胞膜的特性, 使其成为天然的药物载体[55]。目前已有临床试验验证了外泌体治疗疾病的安全性[56], 未来有望成为治疗肿瘤、心脑血管等难治性疾病的突破口。中医药作为传统药物, 在现代研究中能通过多途径、多靶点实现对目标靶器官的调控, 从而发挥临床疗效。在大数据、精准医学的背景下, 更需要对传统药物的有效成分进行研究、分析和提纯, 运用外泌体等更加安全有效的药物载体, 可望实现药物对靶目标器官或细胞进行精确干预。然而, 目前外泌体作为中药载体的研究刚刚起步, 不同疾病如何选择合适的细胞作为外泌体的来源、如何更高效地提纯外泌体与加载药物等问题, 仍是今后需要进一步研究的着力点。

| [1] | Couvreur P, Vauthier C. Nanotechnology:intelligent design to treat complex disease[J]. Pharm Res, 2006, 23: 1417–1450. DOI:10.1007/s11095-006-0284-8 |

| [2] | Alvarez-erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, et al. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes[J]. Nat Biotechnol, 2011, 29: 341–345. DOI:10.1038/nbt.1807 |

| [3] | Théry C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes:composition, biogenesis and function[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2002, 2: 569–579. |

| [4] | Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles:exosomes, microvesicles, and friends[J]. J Cell Biol, 2013, 200: 373–383. DOI:10.1083/jcb.201211138 |

| [5] | Simons M, Raposo G. Exosomes -vesicular carriers for intercellular communication[J]. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2009, 21: 575–581. DOI:10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007 |

| [6] | Roucourt B, Meeussen S, Bao J, et al. Heparanase activates the syndecan-syntenin-alixexosome pathway[J]. Cell Res, 2015, 25: 412–428. DOI:10.1038/cr.2015.29 |

| [7] | Müller G. Microvesicles/exosomes as potential novel biomarkers of metabolic diseases[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2012, 5: 247–282. |

| [8] | Li Z, Ma YY, Wang J, et al. Exosomal microRNA-141 is upregulated in the serum of prostate cancer patients[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2016, 9: 139–148. |

| [9] | Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2007, 9: 654–659. DOI:10.1038/ncb1596 |

| [10] | Filipazzi P, Bürdek M, Villa A, et al. Recent advances on the role of tumor exosomes in immunosuppression and disease progression[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2012, 22: 342–349. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.02.005 |

| [11] | Wang K, Jiang Z, Webster KA, et al. Enhanced cardioprotection by human endometrium mesenchymal stem cells driven by exosomal microRNA-21[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2017, 6: 209–222. DOI:10.5966/sctm.2015-0386 |

| [12] | Gao H, Jiang XG. The progress of novel drug delivery systems[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2017, 52: 181–188. |

| [13] | Batrakova EV, Kim MS. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery[J]. J Control Release, 2015, 219: 396–405. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.030 |

| [14] | Wiklander OP, Nordin JZ, O'Loughlin A, et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting[J]. J Extracell Vesicles, 2015, 20: 26316. |

| [15] | Shahabipour F, Barati N, Johnston TP, et al. Exosomes:nanoparticulate tools for RNA interference and drug delivery[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2017, 232: 1660–1668. DOI:10.1002/jcp.v232.7 |

| [16] | Fujita Y, Yoshioka Y, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicle transfer of cancer pathogenic components[J]. Cancer Sci, 2016, 107: 385–390. DOI:10.1111/cas.2016.107.issue-4 |

| [17] | Taylor DD, Gercel-taylor C. Exosomes/microvesicles:mediators of cancer-associated immunosuppressive microenvironments[J]. Semin Immunopathol, 2011, 33: 441–454. DOI:10.1007/s00281-010-0234-8 |

| [18] | Yeo RW, Lai RC, Zhang B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell:an efficient mass producer of exosomes for drug delivery[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2013, 65: 336–341. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.001 |

| [19] | Zhu W, Huang L, Li Y, et al. Exosomes derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote tumor growth in vivo[J]. Cancer Lett, 2012, 315: 28–37. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.002 |

| [20] | Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Zhao Y, et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson's disease therapy[J]. J Control Release, 2015, 207: 18–30. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033 |

| [21] | Ju S, Mu J, Dokland T, et al. Grape exosome-like nanoparticles induce intestinal stem cells and protect mice from DSS-induced colitiss[J]. Mol Ther, 2013, 21: 1345–1357. DOI:10.1038/mt.2013.64 |

| [22] | Wang Q, Ren Y, Mu J, et al. Grapefruit-derived nanovectors use an activated leukocyte trafficking pathway to deliver therapeutic agents to inflammatory tumor sites[J]. Cancer Res, 2015, 75: 2520–2529. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3095 |

| [23] | Munagala R, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, et al. Bovine milk-derived exosomes for drug delivery[J]. Cancer Lett, 2016, 371: 48–61. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.020 |

| [24] | Bryniarski K, Ptak W, Jayakumar A, et al. Antigen-specific, antibody-coated, exosome-like nanovesicles deliver suppressor T-cell microrna-150 to effector T cells to inhibit contact sensitivity[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2013, 132: 170–181. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.048 |

| [25] | Vashisht M, Rani P, Onteru SK, et al. Curcumin encapsulated in milk exosomes resists human digestion and possesses enhanced intestinal permeability in vitro[J]. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2017. DOI:10.1007/s12010-017-2478-4 |

| [26] | Kim MS, Haney MJ, Zhao Y, et al. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells[J]. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med, 2016, 12: 655–664. DOI:10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.012 |

| [27] | Fuhrmann G, Serio A, Mazo M, et al. Active loading into extracellular vesicles significantly improves the cellular uptake and photodynamic effect of porphyrins[J]. J Control Release, 2015, 205: 35–44. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.11.029 |

| [28] | Johnsen KB, Gudbergsson JM, Skov MN, et al. A compre-hensive overview of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles-endogenous nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014, 1846: 75–87. |

| [29] | Sato YT, Umezaki K, Sawada S, et al. Engineering hybrid exosomes by membrane fusion with liposomes[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 21933. DOI:10.1038/srep21933 |

| [30] | Hadla M, Palazzolo S, Corona G, et al. Exosomes increase the therapeutic index of doxorubicin in breast and ovarian cancer mouse models[J]. Nanomedicine, 2016, 11: 2431–2441. DOI:10.2217/nnm-2016-0154 |

| [31] | Hall J, Prabhakar S, Balaj L, et al. Delivery of therapeutic proteins via extracellular vesicles:review and potential treatments for Parkinson's disease, glioma, and schwannoma[J]. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2016, 36: 417–427. DOI:10.1007/s10571-015-0309-0 |

| [32] | Guo ZR. Development of artemisinin antimalarial drug[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2016, 51: 157–164. |

| [33] | Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases[J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2009, 41: 40–59. DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.010 |

| [34] | Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, et al. Bioavail-ability of curcumin:problems and promises[J]. Mol Pharm, 2007, 4: 807–818. DOI:10.1021/mp700113r |

| [35] | Sun D, Zhuang X, Xiang X, et al. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system:the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes[J]. Mol Ther, 2010, 18: 1606–1614. DOI:10.1038/mt.2010.105 |

| [36] | Taverna S, Fontana S, Monteleone F, et al. Curcumin modulates chronic myelogenous leukemia exosomes composition and affects angiogenic phenotype via exosomal miR-21[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7: 30420–30439. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.v7i21 |

| [37] | Chen J, Xu T, Chen C. The critical roles of miR-21 in anti-cancer effects of curcumin[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2015, 3: 330. |

| [38] | Canfrán-Duque A, Pastor O, Reina M, et al. Curcumin mitigates the intracellular lipid deposit induced by antipsychotics in vitro[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10: e0141829. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0141829 |

| [39] | Kalani A, Kamat PK, Chaturvedi P, et al. Curcumin-primed exosomes mitigate endothelial cell dysfunction during hyperhomocysteinemia[J]. Life Sci, 2014, 107: 1–7. DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2014.04.018 |

| [40] | Gelderblom H, Baker SD, Zhao M, et al. Distribution of paclitaxel in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid[J]. Anticancer Drugs, 2003, 14: 365–368. DOI:10.1097/00001813-200306000-00007 |

| [41] | Patel K, Patil A, Mehta M, et al. Oral delivery of paclitaxel nanocrystal (PNC) with a dual P-gp-CYP3A4 inhibitor:preparation, characterization and antitumor activity[J]. Int J Pharm, 2014, 472: 214–223. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.06.031 |

| [42] | Agrawal AK, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, et al. Milk-derived exo-somes for oral delivery of paclitaxel[J]. Nanomed Nano-technol Biol Med, 2017, 13: 1627–1636. DOI:10.1016/j.nano.2017.03.001 |

| [43] | Cai Q, Ma T, Li C, et al. Catalpolprotects pre-myelinating oligodendrocytes against ischemia-induced oxidative injury through ERK1/2 signaling pathway[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2016, 12: 1415–1426. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.16823 |

| [44] | Zhang XY, Zheng H, Wang YQ, et al. Protective effects of catalpol exosomes on damaged SH-SY5Y cells induced by low serum medium[J]. Global Tradit Chin Med (环球中医药), 2017, 10: 155–158. |

| [45] | Jiang Z, Jacob JA, Loganathachetti DS, et al. β-Elemene:mechanistic studies on cancer cell interaction and its chemosensitization effect[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2017, 8: 105. |

| [46] | Gong M, Liu Y, Zhang J, et al. β-Elemene inhibits cell proliferation by regulating the expression and activity of topoisomerases Ⅰ and Ⅱα in human hepatocarcinoma HepG-2 cells[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 153987. |

| [47] | Zhang J, Zhang HD, Chen L, et al. β-Elemene reverses chemoresistance of breast cancer via regulating MDR-related microRNA expression[J]. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2014, 34: 2027–2037. DOI:10.1159/000366398 |

| [48] | Guo HQ, Zhang GN, Wang YJ, et al. β-Elemene, a com-pound derived from Rhizoma zedoariae, reverses multidrug resistance mediated by the ABCB1 transporter[J]. Oncol Rep, 2014, 31: 858–866. DOI:10.3892/or.2013.2870 |

| [49] | Papa A, Wan L, Bonora M, et al. Cancer-associated PTEN mutants act in a dominant-negative manner to suppress PTEN protein function[J]. Cell, 2014, 157: 595–610. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.027 |

| [50] | Zhang J, Zhang HD, Yao YF, et al. β-Elemene reverses chemoresistance of breast cancer cells by reducing resistance transmission via exosomes[J]. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2015, 36: 2274–2286. DOI:10.1159/000430191 |

| [51] | Ma J, Dey M, Yang H, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive compounds from Tripterygium wilfordii[J]. Phytochemistry, 2007, 68: 1172–1178. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.021 |

| [52] | Aqil F, KausarH, Agrawal AK, et al. Exosomal formulation enhances therapeutic response of celastrol against lung can-cer[J]. Exp Mol Pathol, 2016, 101: 12–21. DOI:10.1016/j.yexmp.2016.05.013 |

| [53] | Yang J, Gao F, Zhang Y, et al. Buyanghuanwu decoction (BYHWD) enhances angiogenic effect of mesenchymal stem cell by upregulating VEGF expression after focal cerebral ischemia[J]. J Mol Neurosci, 2015, 56: 898–906. DOI:10.1007/s12031-015-0539-0 |

| [54] | Chen GH, Yang YJ, Jiang LP, et al. Cardiomyocytes pre-treated with Tongxinluo can increase the phosphorylation of p70S6K1 through the exosomes and reduce the hypoxia/reoxygenation injury of its co-cultured endothelial cells[J]. Chin Circulat J (中国循环杂志), 2016, 31: 29–30. |

| [55] | Ha D, Yang N, Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes:current perspectives and future challenges[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2016, 6: 287–296. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.001 |

| [56] | Morse MA, Garst J, Osada T, et al. A phase Ⅰ study of dexosome immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer[J]. J Transl Med, 2005, 3: 9. DOI:10.1186/1479-5876-3-9 |

2017, Vol. 52

2017, Vol. 52