2015年我国约有47万肝癌新增患者(约占全球60%), 42万人死于肝癌[1]。在全球肝癌的癌症发病率居第5位, 癌症致死率列第2位[2]。肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC)是最为常见的原发性肝癌, 占肝癌的90%左右[3]。在临床上, 肝细胞癌手术切除率低, 可供肝移植的配体极少, 对放、化疗敏感性差, 术后易转移和复发, 且预后极差[4], 因此迫切需要新的治疗方法。

近年来, 随着分子生物学的发展和基因工程技术的日臻成熟以及对癌症发病机制研究的不断深入, 癌症的基因治疗已经发展成为继肝移植、手术切除和放化疗后的新方法[5]。腺相关病毒载体具有持续性表达且能克服其他病毒载体高免疫原性与随机整合到宿主基因而致瘤的缺点等诸多优点, 广泛用于科研和临床的基因治疗而备受青睐[6]。但腺相关病毒载体存在组织细胞靶向性不高, 易造成非靶组织或细胞的不良反应, 而限制了它的应用和发展。如何改造和修饰腺相关病毒载体使其能靶向治疗癌症成了肿瘤基因治疗中极有意义的研究热点。

1 肝细胞癌的发病机制HCC主要由乙型肝炎病毒、丙型肝炎病毒、黄曲霉素、过量饮酒、无机砷和非酒精性肝脏脂肪性变及过度肥胖等原因引起[7-9]。其发生、发展和转移, 与体内控制生长、凋亡的单个或多个基因突变、细胞信号传导通路激活或抑制等密切相关。

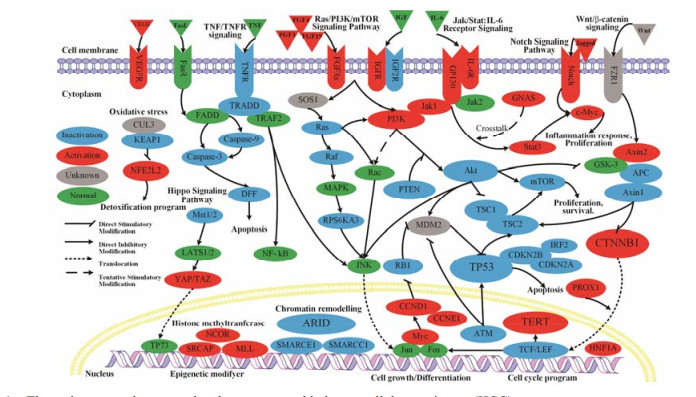

遗传谱系追踪技术分析发现:自我更新与分化的肝癌细胞源自成熟的肝细胞而非肝干细胞[10]。同时基因组分析为HCC发生和进展的主要驱动因子提供了清晰指导。研究发现HCC发病涉及的基因与信号通路(图 1)主要有:影响染色质重塑基因(AT-rich interaction domain, ARID)和肿瘤抑制基因(cellular tumour antigen p53, TP53) 的失活; 人端粒维持基因(human telomere reverse transcriptase, hTERT)和细胞增殖分化基因(catenin beta-1, CTNNB1) 的活化; Ras/PI3K/mTOR信号通路、Wnt/β-catenin信号通路、Notch信号通路和氧化应激通路激活; TNF信号通路的抑制等[3, 11-13]。HCC发病机制的研究为HCC的基因治疗指明了方向。

|

Figure 1 The major mutated genes and pathways recurred in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) |

腺相关病毒(adeno-associated virus, AAV)是一类无被膜的线性单链DNA病毒。基因组中有两个分别编码复制相关蛋白(replication-associated protein, Rep)与衣壳蛋白(capsid protein, Cap)的开放阅读框, 其中, Rep蛋白与腺相关病毒的复制、整合和包装等生命周期有关, Cap蛋白是AAV包装成完整病毒必需的衣壳蛋白[14]。迄今, 已经发现了13种血清型的AAV病毒和100多种不同基因亚型的重组腺相关病毒(recombinant adeno-associated virus, rAAV), 各血清型的来源和受体及辅助受体有所不同, 且不同血清型AAV的组织趋向性有很大差别[6, 15]。

2.2 AAV作为基因治疗载体的优势AAV作为一种理想基因治疗载体具备多种优势: ① 制备工艺成熟。三质粒共转染悬浮HEK293细胞的rAAV生产系统, 已成为视网膜新生血管和B型血友病等的Ⅰ期临床批量生产的规范[16]; ② AAV可在宿主细胞内稳定表达外源基因。AAV介导的目的基因在辅助病毒的帮助下, 复制、包装并表达目的基因[14]; ③ AAV无明显致病性。AAV是一种缺陷型病毒, 不能独立复制, 在无辅助病毒时, 只能整合在宿主细胞染色体中, 呈“潜伏”状态; ④ AAV基因组长约4.7千碱基(kilobase, kb), 其包装容量约为5 kb的DNA片段; ⑤ 定点特异性整合。AAV可定点整合至人染色体的19 q13.3-qter区域, 从而避免基因随机整合而引起的抑癌基因失活或原癌基因激活而导致癌症发生; ⑥ 宿主范围广, 不仅可感染分裂期细胞, 对非分裂期细胞也较敏感。

3 AAV载体介导的HCC靶向策略组织或细胞靶向性是基因治疗安全、高效和准确的重要保障。基因治疗的靶向性策略可以分为以下3个水平:基因转导水平靶向、基因转录水平靶向和转录后调控水平靶向。

3.1 转导靶向性策略AAV通过识别靶细胞表面的受体和/或共受体后黏附到细胞表面, 而后经过受体介导的细胞内吞作用内化, 最后, 在辅助病毒或质粒的协助下, 完成基因的复制和转录。AAV转导细胞的效率与其感染宿主细胞的过程密切相关, 而转导效率主要受衣壳蛋白结构与受体的影响。

3.1.1 AAV衣壳蛋白靶向改造针对AAV与靶细胞识别、内化等过程的关键衣壳蛋白, 将AAV各功能区经基因重组编辑方法进行结构改造与修饰, 使AAV不同血清型具有新的趋向性和组织亲嗜性并提高AAV对靶细胞的转导率(图 2A1)。

|

Figure 2 The strategies of targeting therapy of HCC by AAV. Targeted therapy in transductional level (A), transcriptional level (B) and post-transcriptional level (C) |

Rep蛋白和Rep结合位点是AAV定点整合和稳定存在HCC的必需元件。Ling等[17]优化同源Rep蛋白与ITRs (inverted terminal repeat)以及Cap蛋白的组合, 设计了一种衣壳蛋白S663V+T492V双突变的AAV3-Rep3/ITR3载体, 该载体感染HCC与人肝癌移植瘤鼠模型比野生型AAV分别提高39倍与2倍。Lisowski等[18]在鼠嵌合肝脏模型中, 针对“具有人特异性复制能力”的体外同源重组AAV衣壳文库, 连续筛选得到了一种具有5个亲缘AAV衣壳的rAAV, 在人HCC裸鼠模型中肝脏转染效率是野生型AAV8的100倍, 通过荧光素酶报告基因分析发现该载体仅在人HCC移植瘤模型的肝肿瘤部位发现荧光信号。Grimm等[19]运用DNA家族改组和病毒肽展示技术, 先通过对8种不同野生型AAV衣壳DNA随机同源重组构建衣壳文库, 然后定向进化, 选择体内肝趋向性和体外抗免疫中和的杂合体, 最终成功构建了一种AAV血清型2和8、9的嵌合体——AAV-DJ。Hickey等[20]运用Grim构建的嵌合AAV-DJ载体, 靶向敲除猪的Fah基因, 研究表明敲除靶基因的子代杂合子小猪没有肝脏病症, 能够正常繁殖且表型也是正常的, 该研究是肝脏疾病靶向敲除致病基因的转化研究的重大进步, 也为HCC靶向敲除致癌基因提供参考。

3.1.2 受体与配体靶向修饰用生物或化学方法修饰AAV表面连接特异配体, 通过配体与靶细胞表面受体特异性结合, 从而使AAV载体拥有组织细胞特异性, 引导其靶向转导。因此针对细胞表面受体与配体的改造, 可使AAV成为肝脏靶向性基因治疗的有效病毒载体(图 2A2)。

研究发现不同血清型的AAV进入细胞时结合的受体与共受体等不同, 具有不同的组织细胞趋向性[15], 其中对人肝脏具有趋向性的AAV血清型主要有AAV2、AAV5和AAV8[21]。值得关注的是, 虽然AAV3对肝脏的转导效率很低, 但AAV3可利用肝癌细胞表面肝细胞生长因子受体(hepatocyte growth receptor, HGFR)作为细胞的共受体而提高其感染肝癌细胞能力[22]。随后Cheng等[23]通过突变HGFR基因, 构建的衣壳表面酪氨酸(tyrosine, Y)突变为苯丙氨酸(phenylalanine, F)的AAV3突变体, 研究发现Y705F+Y731F的双突变载体在肝癌细胞的转导表达外源基因比野生型的高10倍。进一步研究发现, 上述双突变载体能显著增强AAV基因治疗功效, 该载体联合一种潜在的化疗药物——紫草素, 能抑制肝肿瘤生长[24]。该研究不仅为靶向载药提供了新方法, 而且为人HCC的基因治疗提供了一种新的治疗药物。

此外, 根据肝癌细胞表面特异性受体, 在AAV衣壳表面设计连有相应配体, 可使包装了治疗基因的rAAV能够特异性与肝癌细胞结合, 从而达到靶向治疗。载脂蛋白E (apolipoprotein E, ApoE)配体可与肝细胞低密度脂蛋白受体特异性结合, Loiler等[25]在AAV2衣壳蛋白的N末端蛋氨酸插入ApoE配体, 制备了一种带有肝细胞膜ApoE配体的AAV, 该AAV/ApoE载体提高了对人肝癌细胞的转导效率并提高了外源基因在靶细胞的表达, 同时该载体与野生型AAV2感染293细胞的效率没有差别, 进一步验证了其转导的靶向性。

3.2 转录靶向性策略细胞或组织特异性启动子使基因在不同细胞和组织中选择性表达, 实现基因转录水平的靶向。通过组织或肿瘤特异性启动子与增强子使外源基因仅在靶细胞内表达, 是提高治疗基因转录靶向性, 减少非靶细胞器官毒性的重要途径(图 2B)。

近年来, 已陆续发现了许多用于基因治疗的肝脏或HCC特异性启动子(表 1)[26-35], 其中最早研究HCC基因治疗的是Su等[26]利用肝脏特异性albumin启动子和甲胎蛋白(alpha-fetoprotein, AFP)特异增强子携带单纯疱疹病毒胸苷激酶(herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase, HSV-TK)基因构建的HCC靶向性载体, 研究发现, 该载体仅对AFP阳性的肝癌细胞有杀伤作用, 对其他非肝癌细胞和AFP阴性的肝癌细胞则没杀伤作用。在HCC的发生发展中, 约56% HCC患者hTERT基因发生激活突变[13], Wang等[27]利用肿瘤特异性hTERT启动子携带肿瘤坏死因子相关凋亡诱导配体(TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, TRAIL)基因构建的AAV-hTERT-TRAIL载体, 在HCC细胞和移植瘤裸鼠模型中, 均有很好的靶向抗肿瘤作用, 而对正常细胞几乎没有影响。随后, 该团队[28]运用顺铂与AAV-hTERT-TRAIL协同抗肿瘤活性的联合疗法, 在体内外均展现了良好的抗HCC生长作用, 该研究进一步验证了hTERT的靶向启动作用。肝脏或肝细胞癌特异性启动子调控靶向, 能在肝组织或HCC细胞中特异性表达外源基因, 避免外源基因对非靶组织的毒副作用, 为HCC的临床基因治疗奠定了基础。

| Table 1 The liver specific promoters using in adeno-associated virus (AAV) based vectors |

RNA干扰(RNA interference, RNAi)技术利用核苷酸组成短的单链微RNA (microRNA, miRNA)或双链RNA (double-stranded RNA, dsRNA), 代替传统反义核酸进行转录后基因沉默[36]。因此, 将含有肝脏或HCC肿瘤关键通路中的RNA靶向元件导入体内, 通过RNA干扰来调控靶基因的表达, 达到转录后水平靶向调控。

在HCC患者中, 某些致癌基因被激活[3], 因此可用致癌基因的miRNA来形成RNA诱导沉默复合体(RNA-induced silencing complex, RISC)抑制癌基因表达(图 2C1)。本课题组Tang[37]运用生物信息学对靶miRNA进行深度测序分析, 寻找并验证了一种具有高表达性能的人工miRNA (artificial miRNA, amiRNA)表达框, 构建的靶向hTERT的scrAAV-amiRNA, 能靶向沉默hTERT。Kim等[38]构建了miR-122a肝靶向性miRNA调节的反式剪接核酶, 通过降低肝癌细胞中维持端粒稳定的hTERT的mRNA水平, 抑制肿瘤细胞增殖, 从而有效地抑制多发性HCC移植瘤小鼠模型肿瘤的生长。Kota等[39]运用AAV在HCC小鼠模型中表达miRNA-26a的miRNA替代疗法, 抑制细胞周期调节蛋白cyclin D2与E2的表达以抑制肝癌细胞的增殖而对正常细胞没有毒副作用。此外, HCC患者的某些基因被抑制或表达降低, 因此可设计一些外源的该基因类似物引导内源RISC与之结合[40], 而内源性靶基因可以更好地表达(图 2C2), Moshiri等[41]设计了一种多重表达内源miR-221关键结位点的“miR-221 sponge”重组AAV-DJ载体, 诱导消耗人肝癌Hep3B细胞内的miR-221, 其通过双荧光素酶报告基因分析实验, 证明了该miR-221 sponge可以靶向消耗内源性miRNA-221, 从而提高细胞周期依赖性激酶抑制剂1B和1C的水平, 抑制肝癌细胞的增殖。为临床提供了安全、高效的HCC治疗策略。

4 AAV介导基因治疗存在的问题腺相关病毒介导的基因治疗在取得不少突破进展的同时, 一些其介导的临床基因治疗问题也有报道。如在AAV介导的血友病基因治疗临床试验中, 观察到CD8+ T细胞的增殖与肝转氨酶循环水平的增加, 同时伴随着免疫T细胞对转导了AAV的肝细胞展现出清除作用[42]。其次, AAV介导的靶基因治疗中如何调控基因的表达水平成为另一个难题[43]。因此, AAV介导的基因治疗设计时应该更加注重其靶向性, 以减少对非靶细胞的毒副作用, 提高AAV基因治疗的有效性和安全性。

5 AAV介导肝细胞癌基因治疗展望基因治疗现已用于临床, 如世界上首个基于重组人5型腺病毒上市的基因治疗药物今又生, 已用于头颈部鳞状细胞癌和肝癌等癌症治疗[44]。AAV携带脂蛋白酯酶基因治疗脂蛋白脂酶缺乏遗传病的Glybera也于2012年被欧洲药品管理局授权销售[45]。AAV载体介导的多种肿瘤和遗传性疾病基因治疗也处于临床试验阶段[46]。运用转导、转录及转录后靶向性策略联合其他肿瘤治疗策略如肿瘤免疫治疗, 以及针对不同患者病因的个性化给药, 提高基因表达疗效与安全性是未来基因治疗发展的方向。随着HCC发病机制逐渐明朗[3, 12], 新的更有效的靶向基因或靶向调控策略的不断发现和相关科学技术的发展如基因编辑技术[47, 48], 相信腺相关病毒载体介导的靶向基因治疗将会在HCC的临床治疗和精准医疗上发挥更加突出的作用。

| [1] | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66: 115–132. DOI:10.3322/caac.21338 |

| [2] | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2015, 65: 87–108. DOI:10.3322/caac.21262 |

| [3] | Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2016, 2: 16018. DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2016.18 |

| [4] | Giannini EG, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, et al. Prognosis of untreated hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2015, 61: 184–190. DOI:10.1002/hep.27443 |

| [5] | Templeton NS. Gene and Cell Therapy:Therapeutic Mechanisms and Strategies[M]. 4th ed. Houston: CRC Press, 2015: 1672-1686. |

| [6] | Xu RA. rAAV Vector:from Virus to Clinic (腺相关病毒——从病毒到临床)[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2014: 2-97. |

| [7] | El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States:where are we? Where do we go?[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 60: 1767–1775. DOI:10.1002/hep.v60.5 |

| [8] | Cai PP, Huang JW, Su CH, et al. Relationship between hepatitis B virus X protein and hepatic cellular cancer[J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2016, 51: 165–173. |

| [9] | Choiniere J, Wang L. Exposure to inorganic arsenic can lead to gut microbe perturbations and hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2016, 6: 426–429. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.07.011 |

| [10] | Shin S, Wangensteen KJ, Teta-Bissett M, et al. Genetic lineage tracing analysis of the cell of origin of hepatotoxininduced liver tumors in mice[J]. Hepatology, 2016, 64: 1163–1177. DOI:10.1002/hep.28602 |

| [11] | Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, et al. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 149: 1226–1239. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061 |

| [12] | Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouze E, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets[J]. Nat Genet, 2015, 47: 505–511. DOI:10.1038/ng.3252 |

| [13] | Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, et al. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2015, 12: 408–424. DOI:10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.103 |

| [14] | Snyder RO, Philippe M. Adeno-Associated Virus:Methods and Protocols[M]. Hatfield: Humana Press, 2011: 74-101. |

| [15] | Lisowski L, Tay SS, Alexander IE. Adeno-associated virus serotypes for gene therapeutics[J]. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2015, 24: 59–67. DOI:10.1016/j.coph.2015.07.006 |

| [16] | Grieger JC, Soltys SM, Samulski RJ. Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors using suspension HEK293 cells and continuous harvest of vector from the culture media for GMP FIX and FLT1 clinical vector[J]. Mol Ther, 2016, 24: 287–297. DOI:10.1038/mt.2015.187 |

| [17] | Ling C, Yin Z, Li J, et al. Strategies to generate high-titer, high-potency recombinant AAV3 serotype vectors[J]. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2016, 3: 16029. DOI:10.1038/mtm.2016.29 |

| [18] | Lisowski L, Dane AP, Chu K, et al. Selection and evaluation of clinically relevant AAV variants in a xenograft liver model[J]. Nature, 2014, 506: 382–386. |

| [19] | Grimm D, Lee JS, Wang L, et al. In vitro and in vivo gene therapy vector evolution via multispecies interbreeding and retargeting of adeno-associated viruses[J]. J Virol, 2008, 82: 5887–5911. DOI:10.1128/JVI.00254-08 |

| [20] | Hickey RD, Lillegard JB, Fisher JE, et al. Efficient production of Fah-null heterozygote pigs by chimeric adenoassociated virus-mediated gene knockout and somatic cell nuclear transfer[J]. Hepatology, 2011, 54: 1351–1359. DOI:10.1002/hep.24490 |

| [21] | Srivastava A. In vivo tissue-tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors[J]. Curr Opin Virol, 2016, 21: 75–80. DOI:10.1016/j.coviro.2016.08.003 |

| [22] | Ling C, Lu Y, Kalsi JK, et al. Human hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a cellular coreceptor for adeno-associated virus serotype 3[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 2010, 21: 1741–1747. DOI:10.1089/hum.2010.075 |

| [23] | Cheng B, Ling C, Dai Y, et al. Development of optimized AAV3 serotype vectors:mechanism of high-efficiency transduction of human liver cancer cells[J]. Gene Ther, 2012, 19: 375–384. DOI:10.1038/gt.2011.105 |

| [24] | Ling C, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Selective in vivo targeting of human liver tumors by optimized AAV3 vectors in a murine xenograft model[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 2014, 25: 1023–1034. DOI:10.1089/hum.2014.099 |

| [25] | Loiler SA, Conlon TJ, Song S, et al. Targeting recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors to enhance gene transfer to pancreatic islets and liver[J]. Gene Ther, 2003, 10: 1551–1558. DOI:10.1038/sj.gt.3302046 |

| [26] | Su H, Chang JC, Xu SM, et al. Selective killing of AFPpositive hepatocellular carcinoma cells by adeno-associated virus transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 1996, 7: 463–470. DOI:10.1089/hum.1996.7.4-463 |

| [27] | Wang Y, Huang F, Cai H, et al. Potent antitumor effect of TRAIL mediated by a novel adeno-associated viral vector targeting to telomerase activity for human hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Gene Med, 2008, 10: 518–526. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-2254 |

| [28] | Wang Y, Huang F, Cai H, et al. The efficacy of combination therapy using adeno-associated virus-TRAIL targeting to telomerase activity and cisplatin in a mice model of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2010, 136: 1827–1837. DOI:10.1007/s00432-010-0841-8 |

| [29] | Glushakova LG, Lisankie MJ, Eruslanov EB, et al. AAV3-mediated transfer and expression of the pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 alpha subunit gene causes metabolic remodeling and apoptosis of human liver cancer cells[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2009, 98: 289–299. DOI:10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.05.010 |

| [30] | Giering JC, Grimm D, Storm TA, et al. Expression of shRNA from a tissue-specific pol Ⅱ promoter is an effective and safe RNAi therapeutic[J]. Mol Ther, 2008, 16: 1630–1636. DOI:10.1038/mt.2008.144 |

| [31] | Chandler RJ, Lafave MC, Varshney GK, et al. Vector design influences hepatic genotoxicity after adeno-associated virus gene therapy[J]. J Clin Invest, 2015, 125: 870–880. DOI:10.1172/JCI79213 |

| [32] | Ziegler RJ, Lonning SM, Armentano D, et al. AAV2 vector harboring a liver-restricted promoter facilitates sustained expression of therapeutic levels of alpha-galactosidase A and the induction of immune tolerance in Fabry mice[J]. Mol Ther, 2004, 9: 231–240. |

| [33] | Berraondo P, Di Scala M, Korolowicz K, et al. Liver-directed gene therapy of chronic hepadnavirus infection using interferon alpha tethered to apolipoprotein A-Ⅰ[J]. J Hepatol, 2015, 63: 329–336. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.048 |

| [34] | Della Peruta M, Badar A, Rosales C, et al. Preferential targeting of disseminated liver tumors using a recombinant adeno-associated viral vector[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 2015, 26: 94–103. DOI:10.1089/hum.2014.052 |

| [35] | Franco LM, Sun B, Yang X, et al. Evasion of immune responses to introduced human acid alpha-glucosidase by liverrestricted expression in glycogen storage disease type Ⅱ[J]. Mol Ther, 2005, 12: 876–884. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.024 |

| [36] | An X, Sarmiento C, Tan T, et al. Regulation of multidrug resistance by microRNAs in anti-cancer therapy[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2017, 7: 38–51. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2016.09.002 |

| [37] | Tang MQ. Study on hTERT Targeting amiRNA Screen and Optimization of Its Expression in scrAAV Vectors (hTERT靶向性amiRNA的筛选及其在scrAAV中的表达优化研究)[D]. Quanzhou: Huaqiao University, 2013. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10385-1014006971.htm |

| [38] | Kim J, Won R, Ban G, et al. Targeted regression of hepatocellular carcinoma by cancer-specific RNA replacement through microRNA regulation[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 12315. DOI:10.1038/srep12315 |

| [39] | Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'donnell KA, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model[J]. Cell, 2009, 137: 1005–1017. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021 |

| [40] | Reichel M, Li J, Millar AA. Silencing the silencer:strategies to inhibit microRNA activity[J]. Biotechnol Lett, 2011, 33: 1285–1292. DOI:10.1007/s10529-011-0590-z |

| [41] | Moshiri F, Callegari E, D'abundo L, et al. Inhibiting the oncogenic mir-221 by microRNA sponge:toward microRNAbased therapeutics for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench, 2014, 7: 43–54. |

| [42] | George LA, Fogarty PF. Gene therapy for hemophilia:past, present and future[J]. Semin Hematol, 2016, 53: 46–54. DOI:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.10.002 |

| [43] | Sun CP, Wu TH, Chen CC, et al. Studies of efficacy and liver toxicity related to adeno-associated virus-mediated RNA interference[J]. Hum Gene Ther, 2013, 24: 739–750. DOI:10.1089/hum.2012.239 |

| [44] | Chen GX, Zhang S, He XH, et al. Clinical utility of recombinant adenoviral human p53 gene therapy:current perspectives[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2014, 7: 1901–1909. |

| [45] | Watanabe N, Yano K, Tsuyuki K, et al. Re-examination of regulatory opinions in Europe:possible contribution for the approval of the first gene therapy product Glybera[J]. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2015, 2: 14066. DOI:10.1038/mtm.2014.66 |

| [46] | Edeistein M:Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide[DB/OL]. Hoboken:The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2016[2017-03-15]. http://www.wiley.com/legacy/wileychi/genmed/clinical/. |

| [47] | Bengtsson NE, Hall JK, Odom GL, et al. Muscle-specific CRISPR/Cas9 dystrophin gene editing ameliorates pathophysiology in a mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy[J]. Nat Commun, 2017, 8: 14454. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14454 |

| [48] | Mak KY, Rajapaksha IG, Angus PW, et al. The adenoassociated virus-a safe and effective vehicle for liver-specific gene therapy of inherited and non-inherited diseases[J]. Curr Gene Ther, 2017, 17: 165. |

2017, Vol. 52

2017, Vol. 52