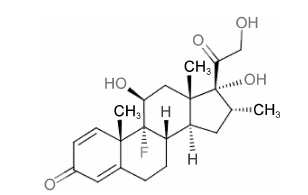

地塞米松 (dexamethasone,DEX) 是一种人工 合成、临床使用广泛的长效糖皮质激素,是泼尼松龙的氟化衍生物,分子式为C22H29FO5,相对分子质量392.46,化学结构如图 1所示,血浆半衰期190 min。它通过与糖皮质激素受体 (glucocorticoid receptor,GR) 结合实现多种药理作用: 主要包括抗炎、抗毒、抗休克和抑制免疫等,因此广泛应用于多种疾病的治疗,如自身免疫性疾病、过敏和炎症等。DEX的抗炎、抗毒和抗休克作用较泼尼松龙更为显著,抗炎活性远大于氢化可的松,但水钠潴留作用和促进排钾作用则相对较弱[1, 2, 3, 4]。

|

Figure 1 The chemical structure of dexamethasone |

近年来,DEX在癌症治疗中的应用日益广泛,它本身并非直接杀死肿瘤细胞,但其通过上述药理作用可以对一些肿瘤具有明显抑制作用,还可大大提高化疗药的抗肿瘤效果以及降低其毒副作用[1]。DEX逐渐被发现的新作用机制及功能使其本身以及和化疗药的联用组合日益显示较好的抗肿瘤应用前景。2015年,FDA批准了抗癌新药Farydak (panobinostat,LBH589) 联合Velcade (bortezomid,硼替佐米) 和DEX用于既往接受至少两种治疗方案 (包括Velcade和一种免疫调节药物) 治疗失败的多发性骨髓瘤患者。本文将对DEX近年来在肿瘤治疗中的主要应用及机制进行如下综述。

1 减少化疗药物副作用化疗引起的恶心和呕吐 (chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting,CINV) 仍然是目前肿瘤治疗中最严重和常见的副作用[5],严重影响患者依从性,而DEX与5-羟色胺3 (5-hydroxytryptamine 3,5-HT3) 受体抑制剂的联用来预防CINV是最常用且有效的方法[6]。在外科甲状腺切除手术术前给予合适剂量DEX,除能有效减少术后恶心和呕吐反应发生几率,还能明显提高5-HT3受体抑制剂雷莫司琼缓解颤抖和疼痛的疗效[7]。在使用化疗药物之后给予DEX可以降低延迟性呕吐的产生。

铂类药物广泛应用于多种恶性肿瘤的治疗且起到良好的治疗效果,但会导致剂量限制性的耳毒性、肾毒性和神经毒性等多种不良反应,接受顺铂治疗的患者中约有60%~80% 会逐渐出现双侧、永久性的听力损失。Salehi等[8]发现,纳米胶囊化的姜黄素与DEX联用可以降低顺铂在几内亚猪模型的耳毒性,有效预防听力损失。此外,一项在转移性非小细胞肺癌 (non-small cell lung cancer,NSCLC) 患者中开展的临床I/II期研究证实,DEX能够在增加卡铂和吉西他滨药效的同时降低血液毒性[9]。

但是,在与化疗药联合治疗时,DEX自身所导致 的不良反应往往无法得以明确评估,原因是很难将其同化疗药物所导致的不良反应区分开来。DEX应用于缓解化疗药物不良反应时所用剂量范围较大,较高剂量 (10~20 mg·d-1) 应用的治疗时间一般较短 (1~5 d),而低剂量 (0.5~1 mg·d-1) 应用的时间较长,通常超过五周,其耐受性一般能保持在可接受的水平上[6, 10, 11, 12]。

2 增加化疗药物的治疗效果在肿瘤治疗中,DEX与化疗药物联用除了可以降低不良反应 (用作保护剂) 外,还可增加化疗药物的治疗效果 (用作增敏剂)。

Wang等[13, 14]研究发现,在结肠癌、肺癌、乳腺癌和神经胶质瘤裸鼠移植瘤模型中,经皮下注射 (sc) DEX(0.1 mg·d-1) 预处理5天之后,可使卡铂和吉西他滨联用的抗肿瘤药效比单用药效增加2~4倍 。DEX预处理使卡铂浓度-时间曲线下面积 (area under the curve,AUC) 增加了200%,峰浓度 (Cmax) 增加了100%,清除率下降了160%,而肿瘤中吉西他滨的摄取也有所增加,表现出良好的化疗增敏剂的特点。DEX (0.1 mg·d-1,sc) 预处理还可以加强阿霉素在4T1乳腺癌动物移植瘤模型中的抗肿瘤效果,主要是通过增加肿瘤中阿霉素的蓄积,调节肿瘤中细胞因子的表达,如增加肿瘤坏死因子-α (tumor necrosis factor α,TNF-α),降低白介素-8β (interleukin-8β,IL-8β) 和血管内皮生长因子 (vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF) 的表达,提高阿霉素对细胞凋亡的诱导和抑制细胞增殖的效果,抑制细胞核中阿霉素引起的核转录因子 (nuclear factor κB,NF-κB) 活性[4]。此外,DEX通过对血管生成的抑制和细胞周期的影响,增加顺铂在小鼠肿瘤模型中的疗效[15]。

虽然有研究认为DEX可作用于细胞周期的G1期,诱导细胞凋亡[16]。但发现,在某些肿瘤细胞中,包括卵巢癌、乳腺癌、肝癌、肺癌、结肠癌、子宫癌、黑色素瘤和神经胶质瘤等,DEX对紫杉醇 (paclitaxel) 诱导的凋亡会产生选择性的抑制[17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22],其抗凋亡作用可能是通过促进DNA的修复、上调抗凋亡Bcl-2家族(Bcl-2和Bcl-XL) 和IAP家族 (survivin) 的表达产生的[22]。DEX也会降低卡铂在NSCLC移植瘤模型中的敏感性,抑制卡帕引起的DNA损伤,下调NF-κB信号通路的表达,减弱卡铂对p53和p21信号通路的激活作用,从而延迟化疗引起的细胞衰老[23]。

3 抑制肿瘤生长近年来的研究结果证明,DEX除了在抗肿瘤的 联合治疗中扮演上述保护剂和增敏剂的重要角色,其本身对一些肿瘤也具有显著抑制作用。相较于泼 尼松龙,DEX应用于儿童急性淋巴细胞白血病中的治疗时并没有更为显著的效果[24],但以单药疗法治疗去势抵抗性前列腺癌时,以前列腺特异性抗原 (prostate-specific antigen,PSA) 为主要临床响应终点,发现其药效优于泼尼松龙,提示DEX在临床去势抵抗性前列腺癌治疗可以作为糖皮质激素中的首要选择[25, 26]。本课题组的近期研究发现,其对某些肿瘤 (如NSCLC) 的药效甚至好于阳性对照 (如化疗药吉西他滨和分子靶向药埃罗替尼等),DEX具有良好的抗癌潜质,这与DEX如下的作用机制密不可分。

3.1 免疫抑制作用糖皮质激素可以调节淋巴细胞中的多种基因从而影响细胞的功能,抑制淋巴细胞增殖并促使其死亡。DEX可以有效抑制淋巴细胞,因此常用于淋巴系肿瘤及白血病的治疗方案中。淋巴细胞主要包括T淋巴细胞、B淋巴细胞和自然杀伤 细胞(natural killer cell,NK细胞)。淋巴瘤的瘤组织内含有大量分化的淋巴细胞。DEX剂量依赖性地抑制T淋巴细胞的过快生长[27]。Petrillo等[28]研究发现,DEX影响T细胞受体 (T-cell receptor,TCR) 信号通路,调节胸腺细胞和淋巴细胞中的Lck和Tec激酶,是糖皮质激素免疫调节的一种可能机制。此外,DEX可以通过多种通路诱导B淋巴细胞的凋亡,包括激活半胱天冬酶,调节白介素,上调促凋亡蛋白BIM、Bax、Bcl-XS和Bak,调节促生存因子如Bcl-2、Bcl-XL、Bcl-w、AP-1和NF-κB[29, 30, 31]。糖皮质激素引起的凋亡过程涉及到基因组和细胞浆多种事件的参与,这种凋亡作用的起始阶段需要GR的反式激活,但是糖皮质激素在细胞浆中的快速起效可能与糖皮质激素引起的凋亡信号通路有关[29]。

众多研究表明,糖皮质激素可以诱导淋巴细胞的凋亡,但DEX诱导其凋亡的机制错综复杂,并未完全清楚。对于糖皮质激素诱导凋亡的机制,目前有两大学派,一类认为死亡诱导基因的激活导致了凋亡的产生,另一类认为糖皮质激素诱导的凋亡是由于抑制转录因子活性,从而抑制生长/生存因子基因的转录[32]。在临床淋巴瘤治疗中,DEX通常与利妥昔单抗、异环磷酰胺、阿糖胞苷、依托泊苷、甲氨蝶呤、阿霉素、吉西他滨或卡铂等抗肿瘤药联用作为复发性或难治性淋巴瘤的挽救疗法,可以显著提高患者生存率[33, 34, 35]。DEX的口服或者静脉注射剂量往往高达40 mg·d-1,给药时间3~5天不等,因此往往伴随多种不良反应的产生。

3.2 抗炎作用肿瘤引发的炎症是近年来发现的肿瘤的重要特征之一[36],炎症介质和细胞因子是肿瘤局部环境的重要成分。在多种类型的癌症中,炎症在发生恶性病变之前就已存在。与之相反,在有些癌症中,肿瘤会诱导炎症微环境的产生,其中包含多种炎症细胞、趋化因子和细胞因子,从而进一步促进肿 瘤的发生发展。靶向这些炎症介质 (趋化因子和细胞因子,如TNF-α和IL-1β)、炎症相关的主要转录因子 (如NF-κB和STAT3) 或炎症细胞可以降低癌症发生率、抑制癌症转移[37, 38]。

DEX的抗炎作用是通过与细胞质中的GR结合实现的,即通过激活GR,形成同源二聚体转移到细胞核中,结合DNA 5' 端的上游启动子区域上的糖皮质激素反应元件 (glucocorticoid receptor element,GRE),直接或者间接调控炎症相关基因的转录与表达[2]。

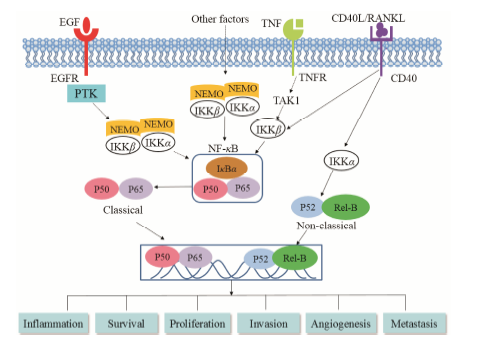

具体而言,糖皮质激素可通过抑制转录因子NF-κB的活化发挥其抗炎作用。NF-κB发现于1986年,这种核因子可结合到B淋巴细胞免疫球蛋白的κB链上的增强子区域,在各种细胞中广泛存在。在静息状态时,这种因子由p50、p65和IκBα组成,以无活性的异源三聚体的形式存在于细胞质中 (参考文献[39, 40],作图 2)。一旦被IL-1β、TNF-α等激活,IκBα蛋白作为一种NF-κB的抑制剂,会发生磷酸化和泛素化,随后降解。释放出的p50和p56转移至细胞核,结合多种基因启动子上的特定DNA序列,启动转录过程。促使IκBα磷酸化的激酶称做IKK,其中IKKβ调节典型的NF-κB激活通路,而IKKα调剂非典型通路[39, 41]。NF-κB及其调控的基因产物对肿瘤的发生起着极为重要的作用,包括肿瘤的增殖、侵袭和转移等。基本所有与炎症相关的基因产物 (如TNF、IL-1、IL-6、趋化因子和COX2等) 都是由NF-κB的激活所调节的,而且NF-κB在绝大多数肿瘤细胞中处于活化状态,而与肿瘤发生相关的许多基因都可以被NF-κB调控[42]。Castro-Caldas等[43]发现,DEX可诱导CCRF-CEM淋巴细胞中IκBα的迅速降解,p50和p56暂时从细胞质转移到细胞核中,形成蛋白- DNA复合物,造成NF-κB的短暂活化,而随后DEX会造成IκBα降解后的从头合成,从而抑制NF-κB的进一步活化。体内外实验证实,DEX可抑制促炎症因子如TNF-α、IL-1β和IL-6的表达,抑制IκBα、p56、IKKα和IKKβ的磷酸化[38]。

|

Figure 2 Association of NF-κB signaling pathway with tumorigenesis. EGF,endothelial growth factor; EGFR,EGF receptor; IKK,IκB kinase; PTK,protein tyrosine kinase; NEMO,NF-κB essential modulator; RANKL,receptor activator for nuclear factor κB ligand; TAK1,transforming growth factor- activated kinase-1; TNFR,TNF receptor |

在雄激素非依赖性前列腺癌DU145移植瘤模 型中,DEX有较为显著的抗肿瘤药效。它对GR的抑制呈剂量依赖性,可以增加IκBα蛋白和细胞质中NF-κB表达,降低IL-6分泌,证实DEX对GR阳性肿瘤的抑制可能机制是对NF-κB-IL-6信号通路的破坏[3]。Saika等[10]在总数为19人的临床试验中,以PSA为临床响应终点佐证了口服DEX (1.5 mg·d-1) 在D2期雄激素非依赖性前列腺癌患者上的抗肿瘤药效,另一临床实验对雄激素阻断治疗失败 (以PSA是否下降为指标) 后的患者给予小剂量DEX (最初 为1.5 mg·d-1,之后减少为0.5 mg·d-1),有治疗效果的患者血清中IL-6的表达量显著下降,其可能机制是对雄激素非依赖性的雄激素受体激活通路的抑制[11]; 该课题组后来在总数为99人的临床试验中再次验证了小剂量DEX (最初为1.5 mg·d-1,之后减少为0.5~1.0 mg·d-1) 对雄激素非依赖性前列腺癌的疗效[12]。在另一种前列腺癌细胞PC-3中,DEX可诱导TGF-β1受体Ⅱ的表达,加强TGF-β1信号通路对细胞的生长抑制作用,抑制NF-κB的转录活性和IL-6 mRNA的表达,发挥抗增殖作用[44]。

Egberts等[45]的研究结果证实,虽然DEX在体 外对胰腺导管腺癌细胞的增殖并无影响,但可以抑制NF-κB通路的活化。在胰腺肿瘤切除后的SCID 小鼠肿瘤模型中,DEX可显著降低局部复发的肿瘤体积,抑制肝脏、脾脏的转移,可用于预防肿瘤的复发和转移。

3.3 抗血管生成病理性的血管生成是肿瘤的特征之一。肿瘤组织同正常组织一样,需要营养成分和氧气维持生存以及代谢废物和二氧化碳的排出,这种需求是由血管生成过程产生的、肿瘤相关的新血管 系统实现的[36]。现在广为接受的观点是,在肿瘤组织中存在“血管生成开关”,这一开关基本一直处于激活和开放的状态,因而使得静止的脉管系统可以持续产生新血管来维持新生肿瘤的生长[46]。血管生成最常见的诱导剂和抑制剂分别为表皮生长因子-A (vascular endothelial growth factor A,VEGF-A) 和血小板反应蛋白-1 (thrombospondin-1,TSP-1)。

糖皮质激素可以抑制血管生成,并非作用于肿瘤细胞生长因子或者直接杀死细胞,从而间接减缓肿瘤的发生发展[1]。较早有研究发现,可的松、氢化可的松、四氢皮质醇和糖皮质激素等类固醇与肝素联用可以抑制肿瘤血管生成,这种抗血管生成作用与肝素的抗凝作用无关,而DEX的抑制血管生成作用的起效浓度远远低于氢化可的松,其作用机制是DEX这类皮质醇可以作用于血管生成有关的肝素酶,从而特异性改变毛细血管上的基底膜更新率,造成毛细血管的退化[47]。

另外,DEX可显著下调DU145细胞中VEGF和IL-8在基因和蛋白水平上的表达,Yano等[48]发现,在DU145移植瘤模型中,DEX可降低肿瘤体积和肿瘤微脉管密度,减少VEGF和IL-8基因水平表达量,而DEX体外对细胞增殖无显著影响,说明DEX通过下调糖皮质激素受体介导的VEGF和IL-8表达,抑制肿瘤相关的血管生成与其发挥抗肿瘤作用密切相关。

低氧诱导因子 (HIF-α) 是细胞在低氧环境时主要的调节因子,可以调节众多下游基因,如VEGF的转录和表达。VEGF是促进肿瘤血管生成最关键的生长因子,它的高表达与血管生成的肿瘤生长关系密切,会造成肿瘤脉管系统的无限扩增,继而导致肿瘤的恶化和转移[49]。肿瘤微脉管密度 (microvessel density,MVD) 是血管生成的重要衡量标准。MVD 较高的肿瘤往往与恶性程度、复发情况和转移密切 相关。在Lewis肺癌裸鼠移植瘤模型中,DEX可以抑制肿瘤的生长且肿瘤组织中HIF-α、VEGF和MVD显著降低,因此DEX下调HIF-α和VEGF的表达从而抑制血管生成对DEX的抗肿瘤药效具有重要作 用[50]。

在膀胱癌细胞中,DEX促进GR介导的受体活性和细胞增殖,促进其凋亡,而侵袭/转移相关的分子,包括金属蛋白酶2 (MMP-2)、MMP-9、IL-6、VEGF以及MVD都被下调,还可诱导间质-上皮细胞转化。此外,DEX会增加IκBα蛋白的表达和NF-κB 在细胞质中的蓄积。在裸鼠移植瘤模型中,DEX虽然增大了肿瘤体积,但是抑制了肿瘤的侵袭和转移[51]。

Villeneuve等[52]的研究发现,虽然DEX会使有抗肿瘤作用的浸润性T细胞大大减少,但仍可以抑制裸鼠恶性胶质瘤的生长并延长其生存期。DEX体外并不能显著影响胶质瘤细胞的生长,所以其抗肿瘤疗效应该是一种间接的作用。DEX可以使肿瘤血管密度略有下降但对血管直径和VEGF-A的表达并无影响,而主要是通过下调血管生成因子血管生成素2 (ANGPT 2) 的表达发挥抗肿瘤药效,这种对肿瘤内皮细胞的作用可能是DEX减缓神经胶质瘤生长的机制。

3.4 调节雌激素水平的内分泌治疗作用糖皮质激素和雌激素是哺乳动物必不可少、但生理学作用完全不同的两类甾类激素。糖皮质激素影响多种细胞进程,如代谢、免疫反应和凋亡等。雌激素是一种影响哺乳动物生殖不可或缺的性激素,对内分泌组织,如乳腺和子宫中的生理功能的调控起重要作用,这些生理作用是通过与核受体雌激素受体 (estrogen receptor,ER) 结合实现的。糖皮质激素经典效应是通过GR 介导实现的,对基因转录的调节作用,而它也可以产生快速的、非基因水平的效应,例如对MAPK/Erk、JNK及Wnt通路的干涉[53]。糖皮质激素与其他激素和信号存在的允许作用较为复杂,其机制尚不完全清楚。有研究发现糖皮质激素对EGFR和VEGFR等生长因子信号通路会产生抑制作用[1, 54],而ER和其他生长因子的表达之间往往存在双向、负相关的关 系[55],因此DEX等糖皮质激素可以间接影响ER的表达,从而影响雌激素依赖性肿瘤与ER相关的内分泌治疗。

大量研究发现体内过高的雌激素水平是乳腺癌产生和发展的重要诱因。女性体内雌激素主要包括雌二醇 (estradiol,E2) 及雌酮 (estrone,E1),它们通过硫酸化形成无活性的甾体硫酸酯: 硫酸雌二醇 (E2S) 及硫酸雌酮 (E1S),而甾体激素和甾体硫酸酯又能通过硫酸转移酶 (sulfotransferase,SULT) 和硫酸酯酶 (sultatase,STS) 进行相互转化。SULT能够催化雌激素的硫酸化反应而使之失去活性,从而降低雌激素水平。在SULT众多家族成员中,雌激素硫酸转移酶 (estrogen sulfotransferase,EST) 对雌激素的亲和力最强,是体内最重要的代谢雌激素的SULT成员[56]。

研究发现,糖皮质激素可以通过作用于GR来诱导EST的表达和活性,从而抑制雌激素反应[57, 58]。DEX可以减弱子宫中雌激素诱导的胰岛素样生长因子-1 (insulin-like growth factor,IGF-1) 的表达,而IGF-1与肿瘤的产生有密切关系[59]。Gong等[60]研究发现,DEX引起GR的活化,可以诱导EST的表达,促使雌激素硫酸化为无生物活性的雌激素硫酸盐,因此降低了体循环系统中过高的雌激素水平。在雌激素依赖型的MCF-7移植瘤模型中,DEX可以抑制肿瘤的生长,具有内分泌治疗作用。

除传统的与雌激素息息相关的乳腺癌、子宫内膜癌和卵巢癌外,最近几年的研究显示雌激素信号通路在肺癌、前列腺癌和大肠癌等肿瘤的起始和发生发展过程中也具有重要作用[61, 62, 63]。本课题组的初步研究证实,DEX在体外对NSCLC A549细胞的凋亡并无显著影响,但在裸鼠移植瘤中却表现出极为显著的肿瘤抑制作用。结果显示,DEX对A549肿瘤细胞中EST的表达具有显著诱导作用,呈剂量依赖性; 并且适当浓度雌激素的加入可以促进A549肿瘤细胞的生存率,而硫酸化反应抑制剂triclosan可以明显逆转DEX对NSCLC细胞增殖的抑制作用,说明雌激素的硫酸化作用在DEX对NSCLC的肿瘤抑制中起重要作用。因此,DEX通过对SULT的诱导而抑制雌激素信号通路的内分泌疗法可能是NSCLC治疗的又一新途径。

4 地塞米松安全性DEX虽可用于多种疾病的治疗,但也存在全身不良反应,包括胃肠道出血、感染和高血糖症等。DEX在应用生理剂量治疗时并无明显不良反应,长期药理剂量的使用往往会并发多种不良反应,如医源性库欣综合征等。糖皮质激素最重要、最危险的不良反应是骨质疏松,另外还有脂肪再分布、高血压、皮肤和肌肉萎缩、白内障、情绪紊乱、易感染、糖尿病以及下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴的抑制等。DEX抗炎作用和免疫抑制作用可诱发或加重感染,降低身体抵抗力。因此,特殊人群如孕产妇、小儿、老年人群,有精神病史,患有骨质疏松、高血压、糖尿病等人群用药需格外谨慎,禁用于感染、脑部疟疾、全身性真菌感染等人群[64, 65, 66, 67, 68]。Karnofsky评分可以用于评价癌症患者在化疗中的生活质量,一项关于DEX应用于转移性脑瘤治疗的研究发现,DEX治疗脑水肿的Karnofsky评分呈剂量依赖性,8 mg·d-1剂量组评分有所提升,而16 mg·d-1剂量组的毒性反应发生率远大于4 mg·d-1和8 mg·d-1[27]。

DEX不良反应的发生及严重程度与其给药剂量、途径和时间等有密切关系,因此优化其给药剂量和方案显得极为重要。紫杉醇输注治疗前12 h和6 h口服20 mg DEX或治疗前30 min静脉注射40 mg DEX是FDA推荐的可以预防紫杉醇引起的重度过敏反应 (severe hypersensitivity reaction,HSR) 的方案,但高剂量的DEX会引起众多不良反应,Köppler等[66]将DEX总剂量从40 mg降至10 mg仍可预防HSR的发生,验证了Bookman[69]和Markman[70]分别将DEX剂量降至静脉注射10或20 mg和20 mg的研究结果。而逐渐降低DEX给药剂量的方案或许也能减少其不良反应发生,DEX剂量从20 mg降至10 mg、2 mg,最后0 mg的逐级递减方案依然能预防乳腺癌患者HSR的发生率[71]。

5 总结与展望DEX在临床使用已有50多年时间,其上市的衍生物已超过12种。DEX在缓解或预防化疗药物不良反应,增强其抗肿瘤药效方面的应用日益广泛。而越来越多的证据表明,DEX通过GR介导抗炎、抗血管生成和激素调节作用,说明DEX抗肿瘤作用机制具有多样化和复杂性。一方面,相对细胞毒类的化疗药物,它对细胞没有直接的杀伤作用使其在肿瘤治疗中具有显著优势; 另一方面,DEX的长期使用会引起库欣综合征、感染、体重增加和各种精神症状等不良反应。因此,DEX和其他抗癌药物的联用策略,以及如何优化给药剂量和方案,使其充分发挥抗肿瘤药效的同时降低不良反应,将具有非常重要的研究和临床应用价值。

| [1] | Rutz HP. Effects of corticosteroid use on treatment of solid tumours [J]. Lancet, 2002, 360: 1969-1970. |

| [2] | Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms [J]. Clin Sci, 1998, 94: 557-572. |

| [3] | Nishimura K, Nonomura N, Satoh E, et al. Potential mechanism for the effects of dexamethasone on growth of androgen- independent prostate cancer [J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2001, 93: 1739-1746. |

| [4] | Wang H, Wang Y, Rayburn ER, et al. Dexamethasone as a chemosensitizer for breast cancer chemotherapy: potentiation of the antitumor activity of adriamycin, modulation of cytokine expression, and pharmacokinetics [J]. Int J Oncol, 2007, 30: 947-953. |

| [5] | Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358: 2482-2494. |

| [6] | Mitsuhashi A, Usui H, Nishikimi K, et al. The efficacy of palonosetron plus dexamethasone in preventing chemoradiotherapy-induced nausea and emesis in patients receiving daily low-dose cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy for uterine cervical cancer: a phase II study [J]. Am J Clin Oncol, 2014, doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000117. |

| [7] | Lee MJ, Lee KC, Kim HY, et al. Comparison of ramosetron plus dexamethasone with ramosetron alone on postoperative nausea, vomiting, shivering and pain after thyroid surgery [J]. Korean J Pain, 2015, 28: 39-44. |

| [8] | Salehi P, Akinpelu OV, Waissbluth S, et al. Attenuation of cisplatin ototoxicity by otoprotective effects of nanoencapsulated curcumin and dexamethasone in a Guinea pig model [J]. Otol Neurotol, 2014, 35: 1131-1139. |

| [9] | Leggas M, Kuo KL, Robert F, et al. Intensive anti-inflammatory therapy with dexamethasone in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: effect on chemotherapy toxicity and efficacy [J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2009, 63: 731-743. |

| [10] | Saika T, Kusaka N, Tsushima T, et al. Treatment of androgen- independent prostate cancer with dexamethasone: a prospective study in stage D2 patients [J]. Int J Urol, 2001, 8: 290-294. |

| [11] | Akakura K, Suzuki H, Ueda T, et al. Possible mechanism of dexamethasone therapy for prostate cancer: suppression of circulating level of interleukin-6 [J]. Prostate, 2003, 56: 106-109. |

| [12] | Komiya A, Shimbo M, Suzuki H, et al. Oral low-dose dexamethasone for androgen-independent prostate cancer patients [J]. Oncol Lett, 2010, 1: 73-79. |

| [13] | Wang H, Li M, Rinehart JJ, et al. Dexamethasone as a chemoprotectant in cancer chemotherapy: hematoprotective effects and altered pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of carboplatin and gemcitabine [J]. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2004, 53: 459-467. |

| [14] | Wang H, Li M, Rinehart JJ, et al. Pretreatment with dexamethasone increases antitumor activity of carboplatin and gemcitabine in mice bearing human cancer xenografts: in vivo activity, pharmacokinetics, and clinical implications for cancer chemotherapy [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2004, 10: 1633-1644. |

| [15] | Arafa HM, Abdel-Hamid MA, El-Khouly AA, et al. Enhancement by dexamethasone of the therapeutic benefits of cisplatin via regulation of tumor angiogenesis and cell cycle kinetics in a murine tumor paradigm [J]. Toxicology, 2006, 222: 103-113. |

| [16] | Chung YJ, Lee JI, Chong S, et al. Anti-proliferative effect and action mechanism of dexamethasone in human medullary thyroid cancer cell line [J]. Endocr Res, 2011, 36: 149-157. |

| [17] | Herr I, Ucur E, Herzer K, et al. Glucocorticoid cotreatment induces apoptosis resistance toward cancer therapy in carcinomas [J]. Cancer Res, 2003, 63: 3112-3120. |

| [18] | Sui M, Chen F, Chen Z, et al. Glucocorticoids interfere with therapeutic efficacy of paclitaxel against human breast and ovarian xenograft tumors [J]. Int J Cancer, 2006, 119: 712-717. |

| [19] | Zhang C, Beckermann B, Kallifatidis G, et al. Corticosteroids induce chemotherapy resistance in the majority of tumour cells from bone, brain, breast, cervix, melanoma and neuroblastoma [J]. Int J Oncol, 2006, 29: 1295-1301. |

| [20] | Zhang C, Kolb A, Buchler P, et al. Corticosteroid co-treatment induces resistance to chemotherapy in surgical resections, xenografts and established cell lines of pancreatic cancer [J]. BMC Cancer, 2006, 6: 61. |

| [21] | Zhang C, Kolb A, Mattern J, et al. Dexamethasone desensitizes hepatocellular and colorectal tumours toward cytotoxic therapy [J]. Cancer Lett, 2006, 242: 104-111. |

| [22] | Hou W, Guan J, Lu H, et al. The effects of dexamethasone on the proliferation and apoptosis of human ovarian cancer cells induced by paclitaxel [J]. J Ovarian Res, 2014, 7: 89. |

| [23] | Ge H, Ni S, Wang X, et al. Dexamethasone reduces sensitivity to cisplatin by blunting p53-dependent cellular senescence in non-small cell lung cancer [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7: e51821. |

| [24] | Igarashi S, Manabe A, Ohara A, et al. No advantage of dexamethasone over prednisolone for the outcome of standard- and intermediate-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Tokyo Children's Cancer Study Group L95-14 protocol [J]. J Clin Oncol, 2005, 23: 6489-6498. |

| [25] | Holder SL, Drabick J, Zhu J, et al. Dexamethasone may be the most efficacious corticosteroid for use as monotherapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer [J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2015, 16: 207-209. |

| [26] | Venkitaraman R, Lorente D, Murthy V, et al. A randomised phase 2 trial of dexamethasone versus prednisolone in castration- resistant prostate cancer [J]. Eur Urol, 2015, 67: 673-679. |

| [27] | Vecht CJ, Hovestadt A, Verbiest HB, et al. Dose-effect relationship of dexamethasone on Karnofsky performance in metastatic brain tumors: a randomized study of doses of 4, 8, and 16 mg per day [J]. Neurology, 1994, 44: 675-680. |

| [28] | Petrillo MG, Fettucciari K, Montuschi P, et al. Transcriptional regulation of kinases downstream of the T cell receptor: another immunomodulatory mechanism of glucocorticoids [J]. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol, 2014, 15: 35. |

| [29] | Smith LK, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of healthy and malignant lymphocytes [J]. Prog Brain Res, 2010, 182: 1-30. |

| [30] | Iglesias-Serret D, de Frias M, Santidrián AF, et al. Regulation of the proapoptotic BH3-only protein BIM by glucocorticoids, survival signals and proteasome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells [J]. Leukemia, 2007, 21: 281-287. |

| [31] | Almawi WY, Melemedjian OK, Jaoude MM. On the link between Bcl-2 family proteins and glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis [J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2004, 76: 7-14. |

| [32] | Greenstein S, Ghias K, Krett NL, et al. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis in hematological malignancies [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2002, 8: 1681-1694. |

| [33] | Li M, Li Y, Yin Q, et al. Treatment with cyclophosphamide, vindesine, cytarabine, dexamethasone and bleomycin in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 2014, 55: 1578-1583. |

| [34] | Elstrom RL, Andemariam B, Martin P, et al. Bortezomib in combination with rituximab, dexamethasone, ifosfamide, cisplatin and etoposide chemoimmunotherapy in patients with relapsed and primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 2012, 53: 1469-1473. |

| [35] | Miura K, Takei K, Kobayashi S, et al. An effective salvage treatment using ifosfamide, etoposide, cytarabine, dexamethasone, and rituximab (R-IVAD) for patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma [J]. Int J Hematol, 2011, 94: 90-96. |

| [36] | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation [J]. Cell, 2011, 144: 646-674. |

| [37] | Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation [J]. Nature, 2008, 454: 436-444. |

| [38] | Jing W, Chunhua M, Shumin W. Effects of acteoside on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in acute lung injury via regulation of NF-κB pathway in vivo and in vitro [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2015, 285: 128-135. |

| [39] | Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV, Sung B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2009, 15: 425-430. |

| [40] | Shostak K, Chariot A. EGFR and NF-κB: partners in cancer [J]. Trends Mol Med, 2015, 21: 385-393. |

| [41] | Yin H, Bai JY, Cheng GF. Effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on the NF-κB activation of HEK293 cells [J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2005, 40: 513-517. |

| [42] | Aggarwal BB, Gehlot P. Inflammation and cancer: how friendly is the relationship for cancer patients? [J]. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2009, 9: 351-369. |

| [43] | Castro-Caldas M, Mendes AF, Carvalho AP, et al. Dexamethasone prevents interleukin-1β-induced nuclear factor- κB activation by upregulating IκB-α synthesis, in lymphoblastic cells [J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2003, 12: 37-46. |

| [44] | Li Z, Chen Y, Cao D, et al. Glucocorticoid up-regulates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) type II receptor and enhances TGF-β signaling in human prostate cancer PC-3 cells [J]. Endocrinology, 2006, 147: 5259-5267. |

| [45] | Egberts JH, Schniewind B, Pätzold M, et al. Dexamethasone reduces tumor recurrence and metastasis after pancreatic tumor resection in SCID mice [J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2008, 7: 1044-1050. |

| [46] | Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases [J]. Nature, 2000, 407: 249-257. |

| [47] | Folkman J, Ingber DE. Angiostatic steroids. Method of discovery and mechanism of action [J]. Ann Surg, 1987, 206: 374-383. |

| [48] | Yano A, Fujii Y, Iwai A, et al. Glucocorticoids suppress tumor angiogenesis and in vivo growth of prostate cancer cells [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2006, 12: 3003-3009. |

| [49] | Bremnes RM, Camps C, Sirera R. Angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer: the prognostic impact of neoangiogenesis and the cytokines VEGF and bFGF in tumours and blood [J]. Lung Cancer, 2006, 51: 143-158. |

| [50] | Geng Y, Wang J, Jing H, et al. Inhibitory effect of dexamethasone on Lewis mice lung cancer cells [J]. Genet Mol Res, 2014, 13: 6827-6836. |

| [51] | Zheng Y, Izumi K, Li Y, et al. Contrary regulation of bladder cancer cell proliferation and invasion by dexamethasone- mediated glucocorticoid receptor signals [J]. Mol Cancer Ther, 2012, 11: 2621-2632. |

| [52] | Villeneuve J, Galarneau H, Beaudet MJ, et al. Reduced glioma growth following dexamethasone or anti-angiopoietin 2 treatment [J]. Brain Pathol, 2008, 18: 401-414. |

| [53] | Kassel O, Herrlich P. Crosstalk between the glucocorticoid receptor and other transcription factors: molecular aspects [J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2007, 275: 13-29. |

| [54] | Kimura M, Moteki H, Ogihara M. Inhibitory effects of dexamethasone on epidermal growth factor-induced DNA synthesis and proliferation in primary cultures of adult rat hepatocytes [J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2011, 34: 682-687. |

| [55] | Giuliano M, Trivedi MV, Schiff R. Bidirectional crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 signaling pathways in breast cancer: molecular basis and clinical implications [J]. Breast Care, 2013, 8: 256-262. |

| [56] | Pasqualini JR. Estrogen sulfotransferases in breast and endometrial cancers [J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2009, 1155: 88-98. |

| [57] | Mitre-Aguilar IB, Cabrera-Quintero AJ, Zentella-Dehesa A. Genomic and non-genomic effects of glucocorticoids: implications for breast cancer [J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2015, 8: 1-10. |

| [58] | Rhen T, Grissom S, Afshari C, et al. Dexamethasone blocks the rapid biological effects of 17β-estradiol in the rat uterus without antagonizing its global genomic actions [J]. FASEB J, 2003, 17: 1849-1870. |

| [59] | Sahlin L. Dexamethasone attenuates the estradiol-induced increase of IGF-I mRNA in the rat uterus [J]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 1995, 55: 9-15. |

| [60] | Gong H, Jarzynka MJ, Cole TJ, et al. Glucocorticoids antagonize estrogens by glucocorticoid receptor-mediated activation of estrogen sulfotransferase [J]. Cancer Res, 2008, 68: 7386-7393. |

| [61] | Kawai H. Estrogen receptors as the novel therapeutic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer [J]. World J Clin Oncol, 2014, 5: 1020-1027. |

| [62] | Yeh CR, Da J, Song W, et al. Estrogen receptors in prostate development and cancer [J]. Am J Clin Exp Urol, 2014, 2: 161-168. |

| [63] | Barzi A, Lenz AM, Labonte MJ, et al. Molecular pathways: estrogen pathway in colorectal cancer [J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2013, 19: 5842-5848. |

| [64] | Vardy J, Chiew KS, Galica J, et al. Side effects associated with the use of dexamethasone for prophylaxis of delayed emesis after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy [J]. Br J Cancer, 2006, 94: 1011-1015. |

| [65] | Ayroldi E, Macchiarulo A, Riccardi C. Targeting glucocorticoid side effects: selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator or glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper? A perspective [J]. FASEB J, 2014, 28: 5055-5070. |

| [66] | Köppler H, Heymanns J, Weide R. Dose reduction of steroid premedication for paclitaxel: no increase of hypersensitivity reactions [J]. Onkologie, 2001, 24: 283-285. |

| [67] | Armstrong TS, Ying Y, Wu J, et al. The relationship between corticosteroids and symptoms in patients with primary brain tumors: utility of the Dexamethasone Symptom Questionnaire- Chronic [J]. Neuro Oncol, 2015, 17: 1114-1120. |

| [68] | Wei YJ, Wang CM, Cai XT, et al. Establishment of zebrafish osteopenia model induced by dexamethasone [J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2013, 48: 255-260. |

| [69] | Bookman MA, Kloth DD, Kover PE, et al. Short-course intravenous prophylaxis for paclitaxel-related hypersensitivity reactions [J]. Ann Oncol, 1997, 8: 611-614. |

| [70] | Markman M, Kennedy A, Webster K, et al. Paclitaxel- associated hypersensitivity reactions: experience of the gynecologic oncology program of the Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center [J]. J Clin Oncol, 2000, 18: 102-105. |

| [71] | Braverman AS, Rao S, Salvatti ME, et al. Tapering and discontinuation of glucocorticoid prophylaxis during prolonged weekly to biweekly paclitaxel administration [J]. Chemotherapy, 2005, 51: 116-119. |

2015, Vol. 50

2015, Vol. 50