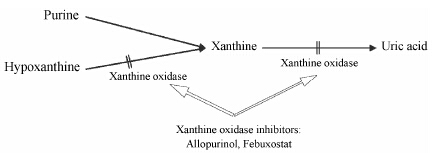

痛风是一类由于人体液中尿酸浓度过高,导致单钠尿酸盐 (monosodium urate,MSU) 结晶析出堆积所导致的关节炎。尿酸是嘌呤代谢途径的终产物 (图 1)。由于人体嘌呤代谢障碍,可能导致尿酸的过多产生或过少排泄,体液中析出的尿酸盐堆积在关节、肌腱、肾脏或其他结缔组织内部及周围,进而引发急性痛风性关节炎反复发作、痛风石沉积、慢性痛风性关节炎、关节畸形以及肾尿酸结石等一系列症状[1, 2, 3]。在西方国家,约1%~2% 的成年男性存在痛风问题[4, 5]。在我国的患病率约为0.15%~0.67%[6]。近年来,随着社会的发展及人们生活水平的提高,痛风的发病率显著升高,且逐渐出现年轻化趋势[7, 8]。目前,痛风已成为继糖尿病之后的第二大代谢性疾病,也是一个重要的致残性疾病。

黄嘌呤氧化酶 (xanthine oxidase inhibitor,XOI) 是嘌呤代谢成尿酸通路上一个重要的酶 (图 1),通 过对其活性的抑制可以减少人体内尿酸的生成,达到降血尿酸的目的。别嘌醇 (allopurinol) 是自上世纪60年代以来临床上常使用的一类XOI,非布索坦 (febuxostat) 是2009年上市的黄嘌呤氧化酶抑制剂。本文采用基于模型的荟萃分析方法,收集现有临床试验中数据,以患者血尿酸降至6 mg·dL-1以下的应答率 (血尿酸应答率,response rate,RR) 作为临床终点,利用模型化的方法对别嘌醇和非布索坦两种药物的药效进行比较。

|

Figure 1 Producing of uric acid and the enzyme in the purine metabolism pathway |

材料与方法 文献检索

在大型医学文献检索数据库PubMed、美国食品药品监督管理局 (http://www.fda.gov/)、欧洲食品药品监督管理局 (http://www.emea.europa.eu/) 和北美临床试验数据中心 (http://clinicaltrial.gov/) 网站上检索发表于1990年1月1日至2012年12月31日之间的相关文献。检索关键词条 [相关治疗药物: febuxostat,allopurinol; 疾病名称: gout,hyperuricemia; 痛风相关临床终点: serum uric acid (sUA,sUR),flare,tophi,tophus],其中同一类别词条之间为“或”的关系,不同类别词条之间为“和”的关系。在所得结果中,根据研究的纳入-排除标准对文献进行筛选和数据摘录。对于同一临床试验相重复报道的研究,如果报道的数据量相等,则剔除重复文献,如果报道的数据量不同,则保留数据最全面的一套研究。

文献的纳入标准: ① 任何上述两药物治疗痛风或高尿酸血症的随机临床试验; ② 合并用药试验,但至少包含上述两种药物之一的单独剂量组; ③ 试验治疗时间不短于1周。

文献的排除标准: ① 动物实验研究或体外研究; ② 单纯的药物动力学研究,给药时间短于1周; ③ 不以血尿酸应答率为临床终点的研究; ④ 非英文的研究; ⑤ 个例研究; ⑥ 单纯的不良反应报告研究。

数据库建立从上述筛选所得的文献中摘录以下的数据信息: ① 临床试验相关信息: 临床试验编号、作者、发表年代、文献来源、临床试验开始年份、临床试验地点、给药形式、临床试验时长、入组患者数、脱落患者数、完成患者数。② 患者相关信息: 受试者类型 (患者/健康受试者)、并发症、年龄、性别数量或百分比 (男/女)、人种百分比 (日本人/高加索人/非裔美国人)、身高、体重、体重指数、肾功能损伤患者百分比 (轻度/中度/重度)、肌酐清除率、血尿酸基础值、背景治疗 (别嘌醇应答者/非应答者)。③ 给药相关信息: 组别、剂量组、治疗药物及其剂量、合并用药及其剂量。④ 临床终点相关信息: 时间、血尿酸值降至6 mg·dL-1的应答率。

模型建立采用模型化的方法对别嘌醇与非布索坦两种药物降血尿酸效果进行比较,采用的临床终点为血尿酸降低至6 mg·dL-1的应答率。应答率为血尿酸降低至6 mg·dL-1以下患者数量与该组患者总数的比值,而不同临床研究中患者总数的统计方法各有所别,包括意向治疗人群 (intent to treat,ITT)、调整意向治疗人群 (modified intent to treat,mITT) 和观测点人群 (observed)。对于ITT、mITT人群数据,需扣除每一个采样时间点的患者脱落量,得到该时间点观测总人数。利用相应研究统计所得的剂量组总人数与观测点总人数之比进行校正,计算得到观测点人群的应答率 (其值为应答率乘以总人数与观测点总人数之比)。

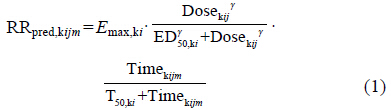

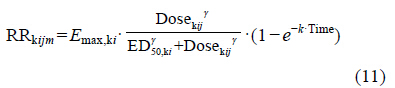

结构模型 采用如下模型对血尿酸下降应答率进行描述:

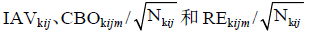

RRpred,kijm代表k药物第i个研究中第j个剂量组的第m个时间点预测的应答率,剂量和应答率间的关系采用Sigmoid Emax模型( ) 拟合,其中Emax,ki表示药物k在研究i中患者能够 达到的平均最大应答率,其范围值为 [0%,100%],ED50,ki表示达到平均最大应答率一半时所需的剂量,γ为Emax模型曲线的形状因子。该应答率中时间变化的影响采用Tmax模型 (

) 拟合,其中Emax,ki表示药物k在研究i中患者能够 达到的平均最大应答率,其范围值为 [0%,100%],ED50,ki表示达到平均最大应答率一半时所需的剂量,γ为Emax模型曲线的形状因子。该应答率中时间变化的影响采用Tmax模型 ( ) 描述,T50,ki表示时间对反应率达到最大影响一半时所需的时间。

) 描述,T50,ki表示时间对反应率达到最大影响一半时所需的时间。

随机效应模型 模型中,共有以下4类随机变异被纳入模型中:

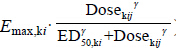

式 (2) 中的 分别表示试验内组间变异、组内不同观测值间的相关关系和残留误差。研究中假设这些影响之间及其与预测值RRpred之间均为加合关系。

分别表示试验内组间变异、组内不同观测值间的相关关系和残留误差。研究中假设这些影响之间及其与预测值RRpred之间均为加合关系。

药效动力学参数的试验间变异 (inter-study variability,ISV) 采用指数型,见式 (3)。

Pi表示第i个试验研究参数,Ppop表示该参数的群体典型值,ηi表示第i个试验的试验间变异,ηi符合均值为0、方差为ωi2的正态分布。ISV通过RRpred,kijm反映到公式2中。

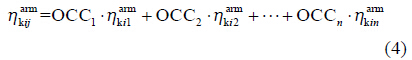

模型中加入的试验组间变异 (inter-arm variability,IAV)[9]以加合型表示 (式4)。

其中,OCC1,OCC2,…,OCCn均为开关变量,表示k药物第i个临床试验中存在的第1、2、…、n个剂量组。 表示这些剂量组间的变异值,服从以0为均值、方差为的同一个正态分布。

表示这些剂量组间的变异值,服从以0为均值、方差为的同一个正态分布。

同一剂量组内不同观测值之间也存在差异,不同观测值间的相关关系 (correlation between observation within an arm,CBO) 采用NONMEM中L2项求算。研究中CBO对于拟合值的影响经观测样本量Nkij的加权 (式5)。

其中,FLG为开关变量,表示k药物第i个临床研究第j个剂量组的第1、2、…、n个观测点。εk1、εk1、…、εkn服从均值为0、方差为σ2/Nkij的同一个正态分布。

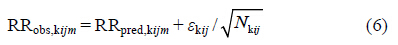

残留误差 (residual error,RE) 经观测样本量Nkij的加权进行描述 (式6)。

其中,εkij服从均值为0、方差为σkij2/Nkij的正态分布。

协变量模型 在结构模型的基础上考察协变 量对参数的影响。协变量模型构建过程中,正向模 型化与逆向剔除分别遵循目标函数值OFV下降大于3.84 (P < 0.05,df= 1) 和OFV增加大于6.63 (P < 0.01,df= 1) 的判断标准。

将待考察的连续型协变量对参数的影响以幂函数的方式加入到基础模型中。以基础血尿酸值为例:

其中,BLsUAij表示第i个研究第j个剂量组中的受试者的平均基础血尿酸值,θBLsUA表示基础血尿酸值的影响系数, 表示纳入研究患者基础血尿酸值的中位值。

表示纳入研究患者基础血尿酸值的中位值。

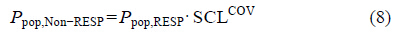

将待考察的分级型协变量通过校正因子SCL表示参数间的差异。以患者背景治疗情况为例:

其中,COV为开关变量,当患者为别嘌醇非应答患者 (RESP) 时,COV取值为1,当患者为别嘌醇应答患者 (non-RESP) 时,COV取值为0。

模型评价与仿真 最终模型使用基础拟合优度图 (basic goodness-of-fit plots,GOF) 进行诊断评价。为评价模型对血尿酸应答率曲线的拟合情况,本研究采用所拟合的参数仿真了1 000个临床试验,所得到的血尿酸应答率曲线95% 预测区间与观测值相比较,仿真的1 000个临床试验的基础血尿酸水平分布与观测数据 (均值9.5 mg·dL-1,标准差0.83 mg·dL-1,区间范围8.48~10.49 mg·dL-1) 相符。此外本研究还通过仿真1 000个临床试验对不同基础血尿酸人群在分别给予非布索坦或别嘌醇时血尿酸应答率随给药剂量或时间的变化进行预测。

所用软件 使用文献管理软件NoteExpress (Version 2.7.1); 利用R (Version 2.15.0) 软件将所提取的数据进行规范化整理,使其符合NONMEM软件 (Version 7.1.2,ICON Development Solutions,Ellicott City,MD,USA) 对数据格式的要求,并实现数据可视化; 用NONMEM进行模型拟合,算法采用考虑 相互作用的一级条件评估法 (first-order conditional estimation method with interaction,FOCE-I),结合R的Xpose软件包 (Version 4.3.2) 进行模型诊断图的绘制。

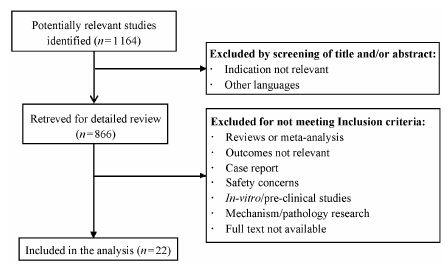

结果 1 文献检索结果与数据库的建立经过文章题目与摘要的初筛以及全文详细信息的筛选 (图 2),最终纳入了22项临床研究。其中,2项研究报道采用末次观测值结转法 (last observation carried forward,LOCF),对试验中缺失的数据采用最近一次数据代替。各研究的详细信息见表 1。共计43个剂量组 (别嘌醇19个治疗组,非布索坦24个治疗组)中的6 365名痛风患者被纳入本荟萃分析中。其 中3个临床试验在日本完成,其他研究均在欧美地 区实施。纳入研究的所有痛风患者平均基础血尿酸 值为9.5 mg·dL-1。4项临床研究中的患者曾使用别嘌醇单独治疗,但治疗效果不足,血尿酸水平仍高于6 mg·dL-1 (即别嘌醇非应答者),这些患者平均基础血尿酸为7.05 mg·dL-1。

|

Figure 2 QUOROM flow diagram indicating study selection criteria for meta-analysis |

|

|

Table 1 Characteristics of the selected clinical studies. aALLO non-responder; bAsian study |

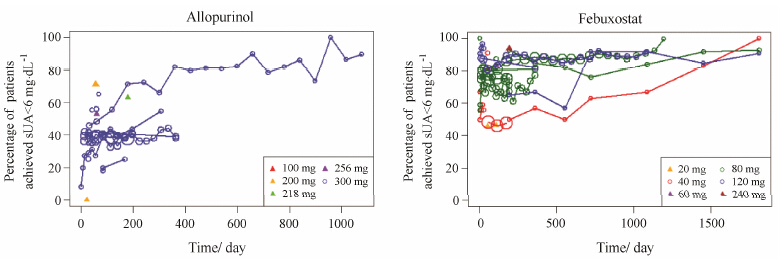

图 3表示观测到的不同剂量的别嘌醇和非布索坦在痛风患者中血尿酸水平下降至6 mg·dL-1以下的按观测点人群计算所得的应答率 (下同) 随时间变化规律。图中观测点的大小与该时刻的样本量成正 比,样本量越大,表明观测值越准确。在别嘌醇的19个治疗组中有14个治疗组为300 mg剂量组,而剩 余5个其他剂量组 (低于300 mg) 每组仅有一个观测点。在这些有限的低于300 mg的剂量组中,未能观察到别嘌醇剂量和应答率之间有显著相关。在长期给药过程中,部分患者由于依从性、不良反应、疗效欠佳等原因从临床试验中脱落,因此别嘌醇血尿酸水平小于6 mg·dL-1的应答率随时间呈现略微上升并趋于稳定的趋势。非布索坦20、40、60、80、120和240 mg这6个剂量分别有2、7、1、10、5和1个独立研究治疗组。从图 3中可以看出非布索坦血尿酸水平小于6 mg·dL-1的应答率随着剂量的增加而增加。

|

Figure 3 Time courses of response rate of sUA < 6 mg·dL-1 ingout patients treated with different doses of allopurinol and febuxostat |

本研究所建立的模型同时纳入了对时间与剂量的考量,但对于别嘌醇而言,由于所获得的临床研究中大部分剂量均为300 mg,无法建立剂量-效应模型,因此将其ED50固定为0,在模型中主要考察其应答率随时间的变化规律。别嘌醇血尿酸水平小于6 mg·dL-1的平均最大应答率为50.8% (90% CI: 23.5%~78.1%)。对于非布索坦,在模型拟合过程中非布索坦Emax和T50估算值分别趋向于100% 和0。因此在最终模型中将其T50固定为0,同时将Emax固定为100%。该结果表明该药物的药效良好,给药后迅速达稳。模型拟合得到非布索坦的ED50值为34.3 mg (90% CI: 31.3~37.3 mg)。

协变量分析表明: 患者基础血尿酸值对别嘌醇的Emax和非布索坦的ED50存在显著性影响。别嘌醇的Emax值与患者基础血尿酸水平成负相关关系,基础血尿酸水平越大,别嘌醇降低血尿酸水平至6 mg·dL-1以下的应答率就越低。而非布索坦的ED50随患者基础血尿酸水平的增加而增大。该结果表明: 患者基础血尿酸水平越高,要达到相同的治疗效果,则需要增加非布索坦的用药剂量。本研究涉及痛风患者中包括了6 158名别嘌醇应答患者与207名别嘌醇非应答患者,基础血尿酸均值分别为9.5和7.05 mg·dL-1,模型结果显示别嘌醇非应答者Emax值与别嘌醇应答患者之间的校正系数为0.587。即在别嘌醇300 mg治疗剂量下,此类患者血尿酸降低至6 mg·dL-1以下的平均最大应答率约为别嘌醇应答者的1/2。两个药物的最终模型分别见式9和10。最终模型所得参数结果见表 2。

|

|

Table 2 Parameter estimates of final model. RSE: Relative standard error%; ISV: inter-study variability |

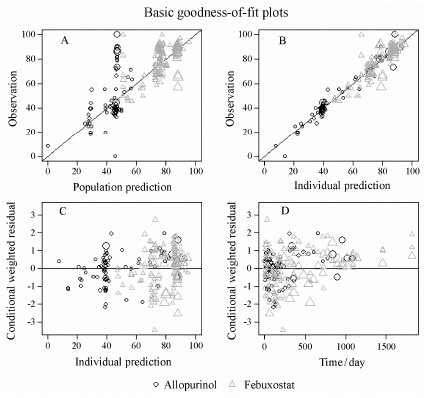

图 4为基础拟合优度图。由图可知,最终模型 均较好地拟合别嘌醇和非布索坦降低血尿酸水平至6 mg·dL-1的应答率。观测值与群体预测值、个体预测值的相关性均较好,观测点均匀地分布于Y = X线的两侧 (图 4A,B); 条件加权残差与个体预测应答率无明显相关性,观测点均匀并集中分布在Y = 0线的两侧 (图 4C)。在治疗时间1 000天以内,条件加权 残差与治疗时间无明显相关性,观测点均匀并集中分布在Y = 0线的两侧 (图 4D)。

|

Figure 4 Basic goodness-of-fit plots for the final model. A: Observed value vs. population predicted response rate. B: observed value vs. individual predicted response rate. C: Conditional weighted residuals vs. population predicted response rate. D: Conditional weighted residuals vs. time. The circle symbols and the triangle symbols represent allopurinol and febuxostat data respectively. The size of the symbol is proportional to the precision |

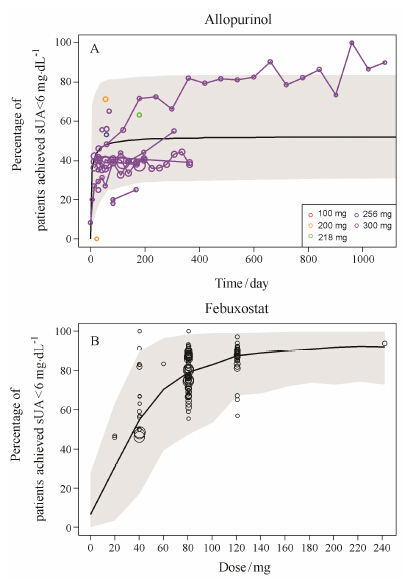

本研究分别仿真得到了别嘌醇降低血尿酸水平至6 mg·dL-1应答率的时间曲线和非布索坦的剂量-应答率曲线 (图 5)。从图中可以看出,绝大部分临床试验的观测点均落在模型95% 预测区间之内,表明所建立的模型能很好的描述应答率随别嘌醇治疗时间和非布索坦治疗剂量的关系。

|

Figure 5 Observed and model-predicted response rate of sUA < 6 mg·dL-1 inpatients treated with (A) allopurinol vs time and (B) febuxostat vs dose. Black line represents model prediction and gray area represents 95% prediction interval. Points represent observed data with size indicating relative patient numbers in each arm |

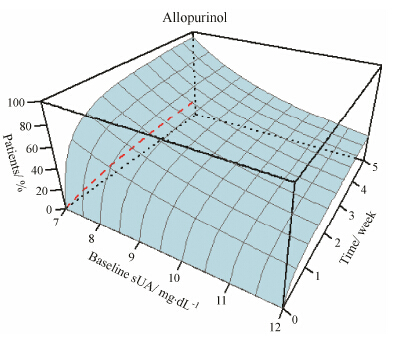

通过对模型的1 000次仿真结果可以看到在不同基础血尿酸值患者中,300 mg剂量下不同时间点的别嘌醇降血尿酸效果 (图 6)。对于血尿酸水平不超过10 mg·dL-1的患者,使用别嘌醇30天血尿酸应答率较高,但是当患者血尿酸水平较高时,别嘌醇难以达到很好的降血尿酸效果,对于基础血尿酸为12 mg·dL-1,在使用别嘌醇30天后,血尿酸降低至6 mg·dL-1的应答率约30%。

|

Figure 6 Predicted response rate in patients with different baseline sUA level after using allopurinol 300 mg. The X- axis stands for time and Y- axis stands for the baseline sUA level (ranging from 7 to 12 mg·dL-1). The Z- axis is the predicted response rate level. Dashed red line represents the response rate curve in allopurinol non-responder populations with a baseline sUA of 7 mg·dL-1 |

非布索坦不同剂量下对模型1 000次仿真,可以考察剂量、基础血尿酸水平与血尿酸应答率三者间的关系 (图 7)。由于非布索坦药物药效较为显著,患者在使用1周后一般能达到较好药效,因此对其仿真也仅考虑患者基础血尿酸水平与使用剂量。仿真结果显示,在较高剂量下血尿酸水平低于10 mg·dL-1的患者能达到100% 的应答率。对于血尿酸水平12 mg·dL-1患者,在使用300 mg剂量下,也能达到80% 应答率。

|

Figure 7 Predicted response rate in patients with different baseline sUA level after using febuxostat. The X- axis stands for the dosage of febuxostat and Y- axis stand for the baseline sUA level (ranging from 7 to 12 mg·dL-1). The Z- axis is the predicted response rate level |

荟萃分析是一种统计方法,通过收集大量试验结果并加以整合,得出或印证结论[36]。基于模型的荟萃分析是在荟萃分析的基础上利用药理学模型和假设,描述药物剂量效应关系或药效随时间变化关系等,在药物研发中发挥着重大作用[37, 38, 39, 40]。一方面,这一方法可以在无平行试验对照的情况下,对不同药物的安全和有效性进行比较,从而为药物研发过程中的决策提供帮助[41]。另一方面,通过模型的方法可以探索患者特性、临床指征等信息对药物治疗效果的影 响,可以更好地为后期临床试验设计提供信息。本研究的目的是通过时间-剂量-效应模型的建立,以血尿酸下降应答率为终点对不同剂量药物的药效进行比较,并通过模型的建立,对患者应答率随时间的变化进行预测。

临床上常以患者血尿酸值 (sUA) 或者血尿酸降低值 (serum uric acid change from baseline,sUA CFB) 为第一临床终点对降血尿酸药物药效进行考察,而血尿酸降至6 mg·dL-1以下的应答率通常作为一些临床试验第二临床终点。然而,研究证实,对于已出现症状的痛风患者,使用降血尿酸药物以维持其血尿酸水平低于尿酸的溶解度 (6.8 mg·dL-1) 十分必要,在一些临床标准中,认为慢性痛风患者应保持血尿酸水平低于6 mg·dL-1。因此,本研究以血尿酸应答率为临床终点,对别嘌醇与非布索坦两种药物药效进行比较。患者血尿酸应答率为血尿酸降低至6 mg·dL-1以下患者数占剂量组患者总数的比例。在22项纳入本研究的临床试验中,不同研究对于剂量组中患者总数的统计计算方法有所差异。因此,在数据库中对相应数据进行了相互转换。以意向治疗人群 (ITT) 为统计方法的研究,其纳入人群包括了所有的随机化分组后的受试者,仅在导入期中被排除的受试者或者入组后没有任何的随访数据的人群可能被排除。调整意向治疗人群 (mITT) 统计方法与ITT的相似,根据导入期实际情况对各剂量组患者数进行了一定调整。部分临床试验按照患者脱落情况,在每个应答率记录的时间点按照观测人数进行统计。按照ITT或mITT两种统计方法计算所得的应答率并没有考虑到患者随试验脱落情况,为此,本研究摘录了根据相应研究中患者脱落的情况,计算出在每个时间点患者实际数量,再以患者实际数为基数,计算出患者应答率。

非布索坦和别嘌醇虽均为黄嘌呤氧化酶抑制药,然而二者在药效上却存在显著差别,这种差异可能来自于不同的作用机制、代谢差异以及不良反应等原因:

① 药物代谢速度差异: 非布索坦口服吸收生物利用度约85%,达峰时间约为1 h,半衰期为5~8 h; 别嘌醇口服生物利用度约80%,其本身并无活性,在进入体内后迅速代谢 (半衰期约为1 h) 成活性代谢物奥昔嘌醇 (oxypurinol),奥昔嘌醇半衰期约23 h。因此,两种药物在代谢速度上的差异可能造成非布索坦药效达稳迅速,而别嘌醇药效达稳较慢[42]。

② 药物作用机制差异: 非布索坦通过与黄嘌呤氧化酶中钼蝶呤中心的结合,对氧化型和还原型黄嘌呤氧化酶均有抑制作用,从而减少尿酸产生; 而别嘌醇仅能抑制还原型的黄嘌呤氧化酶,当结合过程中黄嘌呤氧化酶的钼活性中心发生自氧化时,其药物活性就会降低,上述差异可能造成非布索坦所能达到的患者应答率高于别嘌醇。

③ 不良反应与药物剂量: 根据2011年痛风与高尿酸血症诊断与治疗指南,在患者肾功完全的情况下,别嘌醇最大使用剂量可达800 mg。然而,由于 别嘌醇为嘌呤类似物,除黄嘌呤氧化酶之外,其在体内也可能影响鸟嘌呤脱氨酶、嘧啶核苷磷酸化酶、嘌呤核苷磷酸化酶等的代谢活性,从而容易导致不良反应的发生。约20% 的患者在使用别嘌醇后会出现不良反应,如皮疹、腹泻腹痛、低热等,严重的不良反应包括别嘌醇过敏综合征 (allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome,AHS) 甚至死亡。因此,在临床上通常给予300 mg剂量,对于肾损伤患者,则会选择更低剂量。据统计,在美国约64.9% 的患者使用剂量为300 mg,32.3% 患者使用剂量小于300 mg,仅2.9% 患者使用300 mg以上剂量[43]。在这一剂量水平下,难以满意地将患者血尿酸水平降低至6 mg·dL-1水平以下[7, 44, 45, 46]。非布索坦在结构上并非嘌呤类似物,因此对黄嘌呤氧化酶的抑制具有选择性。非布索坦与低剂量别嘌醇相比表现了更好降血尿酸、溶解痛风石的效果[44, 47],而目前尚未有研究对高剂量别嘌醇与非布索坦药效进行比较。

基于上述原因,本研究中对所建立的时间-剂 量-效应模型进行了条件限定。对于非布索坦,临床试验显示其药效达稳迅速,且患者应答率良好。由于研究纳入的数据均为给药一周后所采集,因此,在模型中将非布索坦T50,FBX固定为0。与此同时,研究尝试采用对数增长模型对数据进行拟合 (公式11)。拟合结果显示,在药物剂量120 mg情况下,kFBX拟合值为0.673,表明非布索坦应答率在一周给药后已基本达稳。因此,模型中可以不考虑时间变量对于患者应答率的影响。与对数增长模型相比,本研究最终所采用的T50模型对不同剂量下非布索坦应答率具有更好的拟合和预测效果 (ΔOFV = -46.16)。

对于别嘌醇,由于纳入的研究中大部分患者使用剂量为300 mg,其余剂量 (100、200、218和256 mg) 分别各只有一篇文献报道其应答率,且并未显现出明显的剂量效应关系 (图 3)。因此,在模型中将其ED50,ALLO固定为0,仅考察别嘌醇300 mg剂量药效随时间的变化。为验证别嘌醇非300 mg剂量组对模型结果的影响,将300 mg剂量组之外的数据删除后,采用原时间-效应模型进行拟合,模型参数拟合结果与原模型结果相似 (患者使用别嘌醇的平均最大应答率拟合值为48.5%)。最终,将别嘌醇ED50固定为 0 mg。

模型中引入了基础血尿酸值 (BLsUA) 和人群类型作为协变量。研究纳入的痛风患者基础血尿酸水 平均值为9.5 mg·dL-1。对于别嘌醇,基础血尿酸值直接影响应答率水平,基础血尿酸水平为10.5 mg·dL-1患者的应答率约为基础血尿酸水平为9.5 mg·dL-1患者应答率的80%。对于非布索坦,基础血尿酸值与ED50,FBX呈正相关,对于基础血尿酸水平10.5 mg·dL-1的患者,其ED50,FBX约为9.5 mg·dL-1水平患者的1.88倍。对于别嘌醇单独用药治疗效果不足的患者,其平均最大应答率与别嘌醇应答患者之间的校正系数拟合值为0.587,表明这些患者再次使用别嘌醇后,仍有约40% 的患者血尿酸水平无法降低至6 mg·dL-1以下。

模型最终采用FOCE-I算法,计算得到的模型结果比较稳定,且参数的相对标准误值均较小,表明参数相对比较准确。模型仿真结果显示,对于血尿酸基础水平较低的患者 (7~8 mg·dL-1),其应答率在30天内基本能达到高于80%水平,而对于血尿酸水平较高患者 (大于10 mg·dL-1),患者应答率在30天内难以达稳,且患者血尿酸下降水平较低,这一结果与临床试验数据相吻合[15, 16]。对于非布索坦,模型预测结果显示不同剂量药效差异显著。在0~50 mg低剂量情况下,血尿酸水平大于9 mg·dL-1患者应答率均低于50%。当剂量大于100 mg·dL-1时,患者应答率较高。对于基础血尿酸水平大于11 mg·dL-1的患者,需使用大于200 mg剂量才能取得较好药效。

结论本研究表明,患者使用别嘌醇治疗的平均最大应答率为50.8%。非布索坦药效良好,给药后药效迅速达稳,模型拟合得到非布索坦的ED50值为34.3 mg。患者基础血尿酸水平与别嘌醇应答率呈负相关,而非布索坦的ED50随患者基础血尿酸水平增加而增大。对于别嘌醇单独用药治疗效果不足的患者,其平均最大应答率与别嘌醇应答患者之间的校正系数为0.587。本研究通过模型化的方法,对别嘌醇和非布 索坦的患者应答率随时间、剂量的变化规律做了进一步探讨,所建立的模型对临床用药及新型降血尿酸药物的研发有一定的指导意义。

| [1] | Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008 [J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2011, 63: 3136-3141. |

| [2] | Richette P, Bardin T. Gout [J]. Lancet, 2010, 375: 318- 328. |

| [3] | Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricemic therapy [J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2004, 51: 321-325. |

| [4] | Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia [J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2012, 64: 1431-1446. |

| [5] | Hamburger M, Baraf HS, Adamson TR, et al. 2011 recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia [J]. Phys Sportsmed, 2011, 39: 98-123. |

| [6] | Chinese Rheumatology Association. The diagnose and treatment guideline of primary gout [J]. Chin J Rheumatol, 2011, 15: 410-413. |

| [7] | Chohan S, Becker MA. Update on emerging urate-lowering therapies [J]. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2009, 21: 143-149. |

| [8] | Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. The changing epidemiology of gout [J]. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol, 2007, 3: 443-449. |

| [9] | Beal SL, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ. NONMEM User's Guide-Part I-VII [M]. Ellicott City, MD: Icon Development Solutions, 1989-2006. |

| [10] | Hollister AS, Becker MA, Terkeltaub R, et al. BCX4208 Synergistically Lowers Serum Uric Acid (sUA) Levels When Combined with Allopurinol in Patients with Gout: Results of a Phase 2 Dose-Ranging Trial [C]. Chicago, IL: American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Scientific Meeting, 2011: 1018. http://www.biocryst.com/PDFs/2788_BioCryst_Hollister_study_M1.3.pdf. |

| [11] | Becker MA, Hollister AS, Terkeltaub R, et al. BCX4208 added to allopurinol increases response rates in patients with gout who fail to reach goal range serum uric acid on allopurinol alone: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [C]. Berlin: EULAR, 2012: FRI0367. http://www.biocryst.com/PDFs/BCRX_BCX4208-203_Becker_EULAR_2012_Poster_3.pdf. |

| [12] | Becker MA, Hollister AS, Terkeltaub R, et al. BCX4208 Combined with Allopurinol Increases Response Rates in Patients with Gout Who Fail to Reach Goal Range Serum Urate on Allopurinol Alone: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial [R/OL]. Biocryst, 2011. http://www.biocryst.com/PDFs/Becker_MA_L10_2h30_08Nov11_W375c_FINAL_v2.pdf. |

| [13] | Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Fernandez-Lopez MJ, et al. Treatment of chronic gout in patients with renal function impairment: an open, randomized, actively controlled study [J]. J Clin Rheumatol, 1999, 5: 49-55. |

| [14] | Panomvana D, Sripradit S, Angthararak S. Higher therapeutic plasma oxypurinol concentrations might be required for gouty patients with chronic kidney disease [J]. J Clin Rheumatol, 2008, 14: 6-11. |

| [15] | Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. Briefing Document for Febuxostat [EB/OL]. Deerfield, Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4387b1-02-takeda.pdf. |

| [16] | Schumacher HJ, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial [J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2008, 59: 1540-1548. |

| [17] | Ipsen Manufacturing Ireland Ltd. Chmp Assessment Report for Adenuric, EMEA/258531/2008 [EB/OL]. London, EMEA, 2008. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/000777/WC500021815.pdf. |

| [18] | European Medicines Agency. FBX_EU label: annex I summary of product characteristics [EB/OL]. EMEA. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000777/WC500021812.pdf. |

| [19] | Becker MA, Schumacher HJ, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout [J]. N Engl J Med, 2005, 353: 2450-2461. |

| [20] | Wells AF, MacDonald PA, Chefo S, et al. African American patients with gout: efficacy and safety of febuxostat vs allopurinol [J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2005, 13: 15. |

| [21] | Jackson RL, Hunt B, MacDonald PA. The efficacy and safety of febuxostat for urate lowering in gout patients >/=65 years of age [J] BMC Geriatr, 2012, 12: 11. |

| [22] | Becker MA, MacDonald PA, Hunt B, et al. Treating hyperuricemia of gout: safety and efficacy of febuxostat and allopurinol in older versus younger subjects [J]. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids, 2011, 30: 1011-1017. |

| [23] | Chohan S, Becker MA, MacDonald PA, et al. Women with gout: efficacy and safety of urate-lowering with febuxostat and allopurinol [J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2012, 64: 256-261. |

| [24] | MacDonald PA, Lloyd E, Lademacher C. Clinical efficacy and safety of successful longterm urate lowering with febuxostat or allopurinol in subjects with gout [J]. J Rheumatol, 2009, 36: 1273-1282. |

| [25] | Naoyuki K, Shin F, Toshikazu H, et al. Placebo-controlled double-blind dose-response study of the non-purine-selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor febuxostat (TMX-67) in patients with hyperuricemia (including gout patients) in Japan: late phase 2 clinical study [J]. J Clin Rheumatol, 2011, 17 (4 Suppl 2): S35-S43. |

| [26] | Kamatani N, Fujimori S, Hada T, et al. An allopurinol-controlled, randomized, double-dummy, double-blind, parallel between-group, comparative study of febuxostat (TMX-67), a non-purine-selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, in patients with hyperuricemia including those with gout in Japan: phase 3 clinical study [J]. J Clin Rheumatol, 2011, 17 (4 Suppl 2): S13-S18. |

| [27] | Naoyuki K, Shin F, Toshikazu H, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the non-purine-selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor Febuxostat (TMX-67) in patients with hyperuricemia including those with gout in Japan: phase 3 clinical study [J]. J Clin Rheumatol, 2011, 17 (4 Suppl 2): S19-S26. |

| [28] | Reinders MK, van Roon EN, Houtman PM, et al. Biochemical effectiveness of allopurinol and allopurinol-probenecid in previously benzbromarone-treated gout patients [J]. Clin Rheumatol, 2007, 26: 1459-1465. |

| [29] | Reinders MK, Haagsma C, Jansen TL, et al. A randomised controlled trial on the efficacy and tolerability with dose escalation of allopurinol 300-600 mg/day versus benzbromarone 100-200 mg/day in patients with gout [J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2009, 68: 892-897. |

| [30] | Reinders MK, van Roon EN, Jansen TL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of urate-lowering drugs in gout: a randomised controlled trial of benzbromarone versus probenecid after failure of allopurinol [J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2009, 68: 51-56. |

| [31] | Cymabay Therapeutics, Inc. FORM 10-K (Annual Report) [R/OL]. Newark, CA: 2014. http://www.otcmarkets.com/edgar/GetFilingPdf?FilingID=9891767. |

| [32] | Shen Z, Yeh L, Kerr B, et al. RDEA594, a novel uricosuric agent, shows significant additive activity in combination with allopurinol in gout patients [C]. Dallas: ASCPT American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics Annual Meeting, 2011. http://www.ardeabio.com/assets/001/5136.pdf. |

| [33] | Yeh L, Kerr B, Shen Z, et al. RDEA94, a novel urat1 inhibitor, shows significant additive urate lowering effects in combination with febuxostat in both healthy subjects and gout patients [C]. Dallas: ASCPT American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics Annual Meeting, 2011. http://www.ardeabio.com/assets/001/5137.pdf. |

| [34] | Ardea biosciences. Biosciences Company Update [R/OL]. Ardea biosciences, 2012. http://www.ardeabio.com/assets/001/5169.pdf. |

| [35] | Sundy J, Perez-Ruiz F, Krishnan E, et al. Efficacy and safety of lesinurad (rdea594), a novel uricosuric agent, given in combination with allopurinol in allopurinol-refractory gout patients: preliminary results from the randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 2b extension study [C]. Chicago: American College of Rheumatology Annual General Meeting, 2011: 1021. http://www.ardeabio.com/assets/001/5161.pdf. |

| [36] | Mandema JW, Gibbs M, Boyd RA, et al. Model-based meta-analysis for comparative efficacy and safety: application in drug development and beyond [J]. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2011, 90: 766-769. |

| [37] | Ahn JE, French JL. Longitudinal aggregate data model-based meta-analysis with NONMEM: approaches to handling within treatment arm correlation [J]. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn, 2010, 37: 179-201. |

| [38] | Mould DR. Model-based meta-analysis: an important tool for making quantitative decisions during drug development [J]. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2012, 92: 283-286. |

| [39] | Ren YP, Deng CH, Wang XP, et al. Comparison study of model evaluation methods: normalized prediction distribution errors vs. visual predictive check [J]. Acta Pharm Sin (药学学报), 2011, 46: 1123-1131. |

| [40] | Sheiner LB, Steimer JL. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling in drug development [J]. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2000, 40: 67-95. |

| [41] | Mandema JW, Boyd RA, DiCarlo LA. Therapeutic index of anticoagulants for prevention of venous thromboembolism following orthopedic surgery: a dose-response meta-analysis [J]. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2011, 90: 820-827. |

| [42] | Stocker SL, McLachlan AJ, Savic RM, et al. The pharmacokinetics of oxypurinol in people with gout [J]. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2012, 74: 477-489. |

| [43] | Sarawate CA, Brewer KK, Yang W, et al. Gout medication treatment patterns and adherence to standards of care from a managed care perspective [J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2006, 81: 925-934. |

| [44] | Perez-Ruiz F. Treating to target: a strategy to cure gout [J]. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2009, 48 Suppl 2: i9-14. |

| [45] | Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physician, Chinese Medical Doctor Association Evidence-Based Medicine Committee. Consensus of Chinese experts on the diagnose and treatment of hyperuricemia combine cardiovascular disease [J]. Chin J Frontiers Med Sci, 2010, 2: 49-55. |

| [46] | Hak AE, Choi HK. Lifestyle and gout [J]. Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2008; 20: 179-186. |

| [47] | Becker MA, Schumacher HJ, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat, a novel nonpurine selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase: a twenty-eight-day, multicenter, phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response clinical trial examining safety and efficacy in patients with gout [J]. Arthritis Rheum, 2005, 52: 916-923. |

2014, Vol. 49

2014, Vol. 49