2. 河北工程大学生命科学与食品工程学院, 邯郸 056038

2. School of Life Sciences and Food Engineering, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan 056038, China

奶牛的产奶量日益增加,然而对于生产性能的过度追求导致了其繁殖力逐年降低,在过去几十年里,全球范围内的奶牛生育率都在下降[1]。据报道,近些年奶牛发情率从80%下降到50%,发情持续时间也从15 h减少到5 h,奶牛单次人工授精的妊娠率每年下降约0.45%~1%[2-3],首次受精怀孕率更是从70%下降到40%[4]。在日本北海道的荷斯坦奶牛,2012和2018年初产母牛的平均受孕率分别为55.2%和39.2%[5]。奶牛能量负平衡(negative energy balance,NEB)导致卵泡发育异常而引起的繁殖力下降,给全球农业经济造成重大损失,几乎所有高产奶牛的国家都受到了影响,成为世界性难题。

NEB干扰奶牛正常的卵巢活动,对产后奶牛的代谢和卵泡正常发育产生不利影响[6],进而影响到奶牛的健康和正常发情周期,降低产奶量和牛奶品质。解决NEB问题势在必行,近些年,组学技术的应用为解决奶牛NEB提供新方法,本文就近年来相关研究进展进行综述及展望,以期为揭示NEB影响奶牛卵泡发育的机制提供参考。

1 奶牛能量负平衡的概述NEB是奶牛在围产期[7](临产前3周至产后3周)经常发生的一种导致机体代谢紊乱的疾病,围产期阶段奶牛体内胎儿发育需要更多营养,同时奶牛开始分泌初乳,干物质采食量(dry matter intake, DMI)需求增加4~6倍[8],然而此阶段奶牛应激严重,采食量下降,能量需求超过了DMI的能量供应[9]。当采食量无法满足正常生理活动和产奶的能量需求时,奶牛可能出现NEB状态[10]。

NEB通常会导致奶牛出现肝功能紊乱、围产期疾病和繁殖性能降低等情况[11-12]。奶牛的脂质代谢在围产期会发生显著变化[13],为了满足能量需求,奶牛体内会进行肝糖异生,脂肪组织和蛋白质被动员起来,大量非酯化脂肪酸(non esterified fatty acid,NEFA)被运输到肝,在肝细胞中氧化或酯化为甘油三酯(TG)[13]。过多的TG再酯化使肝中出现脂肪堆积现象,形成脂肪肝[14],严重的脂肪肝会影响奶牛生殖能力。同时,血浆中过多的NEFA无法完全氧化,产生大量酮体如β-羟丁酸(β-hydroxybutyric acid,BHBA),可能会使奶牛患酮病[15]。NEB使高产奶牛发生代谢紊乱[6],持续存在会导致奶牛体脂减少,体况评分(body condition score,BCS)降低,影响奶牛生产性能和生育能力,NEB的持续时间及其程度因奶牛的遗传性状、产奶量和采食量的不同而产生差异[16]。

2 能量负平衡对奶牛繁殖性能的影响NEB期间,奶牛的免疫力下降,繁殖性能也会被削弱,例如,发情天数、发情次数、发情周期、发情率、受胎率等均会下降。NEB通过多方面因素影响到奶牛的繁殖性能,主要包括激素代谢、能量代谢、体况等。奶牛繁殖过程中,激素代谢起关键的调节作用,奶牛NEB阶段的机体代谢、激素分泌会发生异常。据Radcliff等[17]报道,血清中由胆固醇合成的性类固醇激素(如雌激素和孕酮)水平在围产期期间发生了很大变化。NEB过程中营养不充足,也影响到了与生殖有关的激素合成与分泌,如卵泡刺激素(follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH)[18],激素代谢紊乱会对奶牛发情周期和繁殖力造成影响。

奶牛NEB状态下需要动员机体脂肪组织来产生能量,这时奶牛血清中的BHBA、NEFA浓度升高,血浆中葡萄糖浓度降低[19-20],高浓度NEFA和低浓度葡萄糖对奶牛繁殖性能造成不良影响。在生产中通常以奶牛产后第1周血清中BHBA含量≥1.2 mmol·L-1和第2周BHBA含量≥5.1 mmol·L-1为阈值来预测临床酮症风险[21],据报道,在奶牛产后第2周,血清BHBA浓度超过亚临床酮症(SCK)阈值的奶牛在首次人工授精后怀孕率降低了50%[22]。SCK同样增加了人工授精次数,SCK奶牛每次怀孕的平均授精次数为2.8次,非SCK奶牛为2.0次[23],以上表明NEB阶段时能量代谢异常,同样降低了奶牛的繁殖性能。

NEB影响奶牛BCS,BCS通常作为奶牛管理中的有效指标,其过度增加或减少是影响繁殖性能的一个因素[24],评估BCS是了解营养状况与繁殖性能之间关系的简便方法。奶牛NEB状态下体内脂肪损失较大,它们通常在产犊后的最初几周内减少掉60%或更多的体脂[25],BCS明显降低。Carvalho等[26]证实,产后早期BCS损失最大的奶牛在人工授精后的第1周表现出更多的胚胎发育障碍,与健康群体相比,BCS过度损失的奶牛繁殖性能和存活率降低[24]。另外,Stevenson等[27]报告称,产犊后BCS损失较大的奶牛患牛奶热、酮症、脂肪肝、子宫炎和乳腺炎的风险增加,这些疾病会导致奶牛生育能力下降、产奶量下降、屠宰风险升高[10, 28]。BCS较差还与产后发情延迟、首次产犊和受孕间隔较长以及首次人工授精受孕间隔缩短有关,是造成奶牛繁殖性能下降的重要原因[24]。

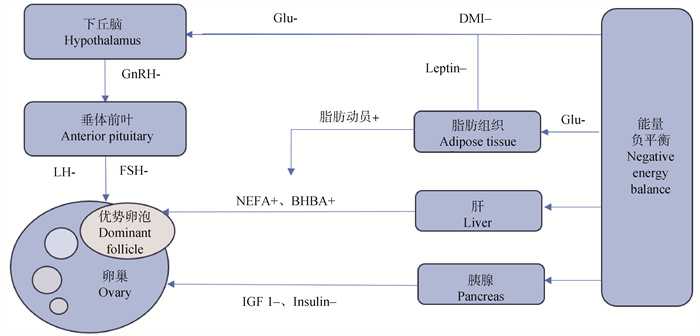

3 能量负平衡影响奶牛卵泡发育的机制 3.1 能量负平衡通过影响激素合成抑制卵巢中的卵泡发育动物合成和分泌激素需要大量营养物质,尤其对蛋白质和能量需求较高。奶牛在NEB状态时,缺乏营养,导致生殖激素的合成能力下降,血浆和卵泡液中的激素水平低下,包括促性腺激素释放激素(gonadotropin-releasing hormone,GnRH)、FSH、促黄体生成素(luteinizing hormone,LH)、瘦素(leptin)等均会受到影响[29]。这些激素通常在下丘脑、垂体和卵巢水平发挥作用,涉及到许多代谢调节与正常卵巢活动相关的复杂内分泌机制的相互作用[30],NEB对卵巢功能的影响主要是通过降低LH脉冲、降低体内IGF-1、机体发生胰岛素抵抗等所实现的[31]。一些研究表明,奶牛产后NEB会延迟卵巢功能的恢复,延长第一个卵泡波,并降低排卵率[32],干扰了奶牛正常排卵,最终导致奶牛繁殖性能下降。

|

图 1 能量负平衡影响奶牛卵泡发育的机制[30] Fig. 1 Mechanism of negative energy balance affecting follicle development in dairy cows[30] |

3.1.1 GnRH GnRH是一种调节哺乳动物生殖功能关键作用的激素,是由位于弓状核和下丘脑视前区的特定下丘脑神经元合成的十肽[33]。生殖内分泌系统由下丘脑-垂体-性腺(HPG)轴组成,精确调节哺乳动物的生殖过程[34],下丘脑分泌的促GnRH调节腺垂体中促性腺激素的合成和分泌,从而调节性腺功能。GnRH促进FSH的合成和分泌,调节动物生长繁殖,在卵泡发育中起重要作用[35],目前,GnRH被广泛用于调节动物繁殖[36]。产后恢复排卵的关键驱动因素是LH脉冲频率的增加,LH脉冲频率又受到GnRH高频脉冲的控制[37],奶牛NEB时GnRH水平低下,影响了FSH、LH的脉冲频率,卵泡的选择及发育受到干扰。

3.1.2 FSH FSH是由垂体前叶产生的一种由α和β亚基组成的二聚体糖蛋白,是一种促性腺激素,在配子发生和成熟的调节中起着至关重要的作用[38]。FSH在卵泡生长和颗粒细胞功能中起关键作用[39],卵泡发育过程中需要依靠FSH、LH等激素的调节,FSH、LH协同促进发育成熟的卵泡分泌雌激素和排卵[40]。FSH的每一次增加都会导致卵泡波的出现,在卵泡发育后期,其生长明显依赖于垂体促性腺激素FSH和LH,这些激素通过下丘脑-垂体的负抑制反馈回路保障了控制卵泡招募、选择和优势的主要机制[41]。

奶牛排卵是正常发情的保障,无排卵乏情是由于优势卵泡(dominant follicle, DF)无法正常排卵导致的乏情[42]。处于NEB状态的奶牛,FSH合成能力下降[17],导致对DF的选择出现差错:颗粒细胞在FSH刺激下将雄激素芳香化生成雌二醇[43-44],此时由于FSH水平较低,奶牛DF中的颗粒细胞无法受到足够的刺激产生一定浓度的雌二醇来诱导排卵,导致DF闭锁[45],奶牛不发情。

3.1.3 LH LH是由垂体前叶合成和分泌的一种促性腺激素,负责诱导排卵、准备受精卵母细胞植入子宫,以及通过刺激膜细胞和黄体化颗粒细胞来产生卵巢黄体酮[37]。LH在卵泡发育过程中发挥重要作用,它刺激关键类固醇激素雌激素的合成和分泌,从而促进卵巢中卵泡的生长和发育[46]。产后恢复排卵的关键因素是LH脉冲频率的增加,LH脉冲频率是影响所选DF最终命运的主要决定因素[47],在招募阶段之后,由于雌二醇和抑制素的负反馈,FSH从被招募的卵泡下降到卵泡进一步选择的阈值以下,此时DF可以使用LH来支持其继续生长[48]。当奶牛发生NEB时,体况不佳加上营养水平低,生殖激素LH分泌水平降低,生长发育到更大尺寸的卵泡数量就会减少[49],因此排卵率下降,发情率降低。

3.1.4 瘦素 瘦素是一种主要由脂肪细胞产生和分泌的激素[50],其他非脂肪组织也可以产生瘦素,例如下丘脑、腺垂体和乳腺对生殖功能至关重要的组织[51-52]。瘦素是向中枢神经系统发送动物营养状况信号的主要因素,因此参与能量代谢和生殖功能相关的调节[53]。瘦素控制着女性生殖系统的正常生理机能,它通过一种将能量稳态与生殖联系起来的复杂机制与下丘脑-垂体-性腺(HPG)轴相互作用,并调节瘦素受体(LEP-R)的丰度[54],这些受体的激活可能导致各种功能和途径的调节,例如:GnRH、FSH和LH浓度的调节[55-56]。在母牛发情周期的卵泡期,血清瘦素浓度与DF的卵泡液中孕酮浓度呈正相关[57]。有证据表明,卵母细胞成熟过程中使用瘦素处理可改善牛的胚胎发育[58],瘦素还可以用作抗凋亡和抗氧化促进剂,以支持体外胚胎发育,特别是在胚胎冷冻保存出现的氧化应激状态下[59]。奶牛分娩前后出现NEB影响血浆中瘦素浓度,妊娠晚期血浆中瘦素水平很高,并在分娩时下降到最低点[60],正常的卵巢周期受到干扰,导致奶牛生育能力下降。

3.2 INS/IGF系统对卵泡的影响胰岛素(insulin,INS)被认为是类固醇生成、卵泡生长、卵母细胞成熟和之后胚胎发育的关键媒介,因为它与促性腺激素分泌相关[45]。胰岛素样生长因子-1(insulin -like growth factor-1, IGF-1)是一种结构上与INS相关的70个氨基酸肽,在体外胚胎发育过程中影响细胞生长和分化并具有抗凋亡作用[61]。在许多物种中,IGF-1的受体和IGF结合蛋白在准备子宫内膜植入胚胎以及胚胎生长发育方面起着重要作用[62]。INS可刺激颗粒细胞的增殖,血液中INS的平均浓度降低会导致奶牛发情周期不规律[63]。

IGF-1是NBE奶牛恢复周期性能力的良好预测指标。IGF-1通过增强促性腺激素在卵巢中的作用,也刺激卵泡生长和雌二醇合成,血浆中IGF-1浓度降低和营养不足会导致卵泡生长速度降低甚至不排卵[64]。据报道,IGF-1敲除的小鼠卵泡无法到达窦期,因排卵不足而导致不孕[65]。INS、IGF-1与LH的联合作用能促进优势卵泡的形成[66],NEB严重的奶牛血浆中INS、IGF-1和葡萄糖的浓度较低,从而降低LH脉冲频率,减少了卵泡合成雌二醇的水平[67]。NEB奶牛体内葡萄糖浓度处于较低水平,导致胰高血糖素浓度上升,胰岛素浓度下降[68]。有研究比较了NEB奶牛组血浆与正常奶牛组血浆后发现,INS、IGF-1浓度在NEB奶牛组更低,NEB奶牛组卵泡的生长速度显著低于正常奶牛组[69],奶牛发情率处于较低水平。

3.3 能量负平衡对卵泡能量代谢的影响卵母细胞是哺乳动物体内最大的细胞,相对其他体细胞,其发育消耗更多的能量。另一方面,胚胎发育初始所需的能量和底物由卵母细胞提供,因此正常的能量代谢在卵母细胞生长和胚胎发育方面显得尤为重要。葡萄糖代谢和脂肪酸氧化是哺乳动物细胞摄取能量的两种常规方式,在细胞质中,葡萄糖和脂肪酸先转化为乙酰辅酶A,最后被氧化为三磷酸腺苷提供能量,虽然两种物质提供的底物最终的氧化方式不同,但是氧化过程都在细胞的线粒体中进行,而脂肪酸氧化可以产生更多的能量[70]。

3.3.1 葡萄糖 葡萄糖是所有哺乳动物细胞能量需求的重要代谢底物,它是一种亲水性分子,不能透过质膜,其摄取是由许多葡萄糖转运蛋白介导的[71]。葡萄糖是牛卵母细胞成熟所必需的能量底物,在培养液中添加葡萄糖可以促进卵母细胞的糖酵解,在体外成熟的卵母细胞中,较高的糖酵解率反映了较高的发育能力[72]。卵丘和卵母细胞复合体通过糖酵解和磷酸戊糖途径代谢葡萄糖,葡萄糖的代谢物与调节卵母细胞减数分裂有关[72],这表明,卵母细胞在成熟期获得发育能力需要足够的葡萄糖,维持最佳的葡萄糖生理浓度直到囊胚期,对于卵母细胞成熟和随后的发育至关重要[73]。NEB与血液中低浓度的葡萄糖密切相关,由低葡萄糖水平而引起促性腺激素分泌的变化会降低FSH和LH浓度,从而导致LH峰缺失进而无排卵[74]。奶牛NEB期间血浆葡萄糖浓度很低,通常不高于3.0 mmol·L-1[75],不利于卵母细胞发育,进而影响到奶牛排卵,奶牛繁殖率下降。

3.3.2 脂肪酸 Bertevello等[76]利用脂质组学技术发现,脂肪酸在卵泡环境中广泛存在,在卵母细胞、卵丘细胞、其他卵泡细胞以及卵泡液中均可观察到脂肪酸。在卵母细胞中,甘油三酯主要以脂滴的形式存在,脂滴是一种重要的能量储存形式,尽管各个物种在不同发育阶段的脂滴含量差异很大,但哺乳动物卵母细胞通常富含脂质,以确保减数分裂有足够的能量供应[77]。NEFA也存在于细胞质中,可以直接从脂滴转运到线粒体,通过β-氧化,快速简便地获取能量。用于产生能量的脂肪酸通过脂肪酸转运蛋白从循环系统或通过脂质双层直接扩散进入细胞,卵泡液中的NEFA也可能通过类似的机制进入卵丘细胞和卵母细胞[78]。奶牛NEB状态下,体内脂肪动员,血浆和卵泡液中的NEFA处于较高水平,高浓度的饱和NEFA会影响颗粒细胞的增殖,降低颗粒细胞活力,对滤泡细胞、卵母细胞减数分裂和胚胎发育也产生不利影响[79-80]。长期暴露在高浓度NEFA带来的有害影响统称为脂毒性,脂毒性损害细胞结构和功能,导致奶牛器官和机体损伤,奶牛的生殖性能受到极大影响[81]。有研究表明,给奶牛口服丙二醇可有效增加其血浆中的葡萄糖浓度,降低BHBA和NEFA水平,缓解奶牛NEB,预防酮症[12]。此外,由于血浆中葡萄糖水平升高,奶牛的繁殖性能和免疫功能也会适当提高。

4 展望奶牛NEB通过影响奶牛的下丘脑-垂体-卵巢轴的激素分泌以及卵泡的能量代谢而影响卵泡发育,奶牛的发情周期受到干扰,影响到正常生产,给畜牧业造成了极大损失。改善奶牛NEB问题,有助于奶制品行业的发展,更有利于我国畜牧业振兴。近年来,得益于组学技术的快速发展,人们对于奶牛NEB的认识越来越清晰,为解决奶牛NEB提供了宝贵的理论依据。然而现有的研究无法完全解决奶牛NEB问题,在未来,随着奶牛生产管理经验的逐渐丰富、组学分析技术的进一步发展,奶牛NEB的分子机制将逐步揭示,为提高奶牛繁殖力、生产效率提供重要实践积累和理论依据,奶牛NEB问题有望得到妥善解决。

| [1] |

FRIGGENS N C, DISENHAUS C, PETIT H V. Nutritional sub-fertility in the dairy cow: towards improved reproductive management through a better biological understanding[J]. Animal, 2010, 4(7): 1197-1213. DOI:10.1017/S1751731109991601 |

| [2] |

ROYAL M, MANN G E, FLINT A P F. Strategies for reversing the trend towards subfertility in dairy cattle[J]. Vet J, 2000, 160(1): 53-60. DOI:10.1053/tvjl.1999.0450 |

| [3] |

BUTLER S T, MARR A L, PELTON S H, et al. Insulin restores GH responsiveness during lactation-induced negative energy balance in dairy cattle: effects on expression of IGF-I and GH receptor 1A[J]. J Endocrinol, 2003, 176(2): 205-217. DOI:10.1677/joe.0.1760205 |

| [4] |

DOBSON H, WALKER S L, MORRIS M J, et al. Why is it getting more difficult to successfully artificially inseminate dairy cows?[J]. Animal, 2008, 2(8): 1104-1111. DOI:10.1017/S175173110800236X |

| [5] |

UKITA H, YAMAZAKI T, YAMAGUCHI S, et al. Environmental factors affecting the conception rates of nulliparous and primiparous dairy cattle[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2022, 105(8): 6947-6955. DOI:10.3168/jds.2022-21948 |

| [6] |

SWARTZ T H, MOALLEM U, KAMER H, et al. Characterization of the liver proteome in dairy cows experiencing negative energy balance at early lactation[J]. J Proteomics, 2021, 246: 104308. DOI:10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104308 |

| [7] |

DRACKLEY J K. ADSA Foundation Scholar Award.Biology of dairy cows during the transition period: the final frontier?[J]. J Dairy Sci, 1999, 82(11): 2259-2273. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75474-3 |

| [8] |

ROCHE J F, MACKEY D, DISKIN M D. Reproductive management of postpartum cows[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2000, 60-61: 703-712. DOI:10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00107-X |

| [9] |

STRĄCZEK I, MŁYNEK K, DANIELEWICZ A. The capacity of Holstein-Friesian and Simmental cows to correct a negative energy balance in relation to their performance parameters, course of lactation, and selected milk components[J]. Animals (Basel), 2021, 11: 1674. |

| [10] |

XU W, VAN KNEGSEL A, SACCENTI E, et al. Metabolomics of milk reflects a negative energy balance in cows[J]. J Proteome Res, 2020, 19(8): 2942-2949. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00706 |

| [11] |

CARVALHO M R, PEÑAGARICANO F, SANTOS J E P, et al. Long-term effects of postpartum clinical disease on milk production, reproduction, and culling of dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2019, 102(12): 11701-11717. DOI:10.3168/jds.2019-17025 |

| [12] |

ZHANG F, NAN X M, WANG H, et al. Effects of propylene glycol on negative energy balance of postpartum dairy cows[J]. Animals (Basel), 2020, 10(9): 1526. |

| [13] |

KONG Y Z, ZHAO C X, TAN P P, et al. fgf21 reduces lipid accumulation in bovine hepatocytes by enhancing lipid oxidation and reducing lipogenesis via AMPK signaling[J]. Animals (Basel), 2022, 12(7): 939. |

| [14] |

PRALLE R S, ERB S J, HOLDORF H T, et al. Greater liver PNPLA3 protein abundance in vivo and in vitro supports lower triglyceride accumulation in dairy cows[J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 2839. DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-82233-0 |

| [15] |

GULIŃSKI P. Ketone bodies-causes and effects of their increased presence in cows' body fluids: A review[J]. Vet World, 2021, 14(6): 1492-1503. |

| [16] |

MOORE S M, DEVRIES T J. Effect of diet-induced negative energy balance on the feeding behavior of dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2020, 103(8): 7288-7301. DOI:10.3168/jds.2019-17705 |

| [17] |

RADCLIFF R P, MCCORMACK B L, CROOKER B A, et al. Plasma hormones and expression of growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor-I mRNA in hepatic tissue of periparturient dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2003, 86(12): 3920-3926. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)74000-4 |

| [18] |

RIBEIRO E S, LIMA F S, GRECO L F, et al. Prevalence of periparturient diseases and effects on fertility of seasonally calving grazing dairy cows supplemented with concentrates[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2013, 96(9): 5682-5697. DOI:10.3168/jds.2012-6335 |

| [19] |

SONG Y X, LOOR J J, LI C Y, et al. Enhanced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the mammary gland of cows with clinical ketosis[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2021, 104(6): 6909-6918. DOI:10.3168/jds.2020-19964 |

| [20] |

GARTNER T, GERNAND E, GOTTSCHALK J, et al. Relationships between body condition, body condition loss, and serum metabolites during the transition period in primiparous and multiparous cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2019, 102(10): 9187-9199. DOI:10.3168/jds.2018-15762 |

| [21] |

KERWIN A L, BURHANS W S, MANN S, et al. Transition cow nutrition and management strategies of dairy herds in the northeastern United States: Part Ⅱ-Associations of metabolic-and inflammation-related analytes with health, milk yield, and reproduction[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2022, 105(6): 5349-5369. DOI:10.3168/jds.2021-20863 |

| [22] |

WALSH R B, WALTON J S, KELTON D F, et al. The effect of subclinical ketosis in early lactation on reproductive performance of postpartum dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2007, 90(6): 2788-2796. DOI:10.3168/jds.2006-560 |

| [23] |

RUTHERFORD A J, OIKONOMOU G, SMITH R F. The effect of subclinical ketosis on activity at estrus and reproductive performance in dairy cattle[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2016, 99(6): 4808-4815. DOI:10.3168/jds.2015-10154 |

| [24] |

MANRIQUEZ D, THATCHER W W, SANTOS J E P, et al. Effect of body condition change and health status during early lactation on performance and survival of Holstein cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2021, 104(12): 12785-12799. DOI:10.3168/jds.2020-20091 |

| [25] |

TAMMINGA S, LUTEIJN P A, MEIJER R G M. Changes in composition and energy content of liveweight loss in dairy cows with time after parturition[J]. Livest Prod Sci, 1997, 52(1): 31-38. DOI:10.1016/S0301-6226(97)00115-2 |

| [26] |

CARVALHO P D, SOUZA A H, AMUNDSON M C, et al. Relationships between fertility and postpartum changes in body condition and body weight in lactating dairy cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2014, 97(6): 3666-3683. DOI:10.3168/jds.2013-7809 |

| [27] |

STEVENSON J S, BANUELOS S, MENDONCA L G D. Transition dairy cow health is associated with first postpartum ovulation risk, metabolic status, milk production, rumination, and physical activity[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2020, 103(10): 9573-9586. DOI:10.3168/jds.2020-18636 |

| [28] |

MOHTASHAMIPOUR F, DIRANDEH E, ANSARI-PIRSARAEI Z, et al. Postpartum health disorders in lactating dairy cows and its associations with reproductive responses and pregnancy status after first timed-AI[J]. Theriogenology, 2020, 141: 98-104. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2019.09.017 |

| [29] |

D'OCCHIO M J, BARUSELLI P S, CAMPANILE G. Influence of nutrition, body condition, and metabolic status on reproduction in female beef cattle: A review[J]. Theriogenology, 2019, 125: 277-284. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.11.010 |

| [30] |

DISKIN M G, MACKEY D R, ROCHE J F, et al. Effects of nutrition and metabolic status on circulating hormones and ovarian follicle development in cattle[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2003, 78(3-4): 345-370. DOI:10.1016/S0378-4320(03)00099-X |

| [31] |

BEAM S W, BUTLER W R. Energy balance, metabolic hormones, and early postpartum follicular development in dairy cows fed prilled lipid[J]. J Dairy Sci, 1998, 81(1): 121-131. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75559-6 |

| [32] |

XU W, VERVOORT J, SACCENTI E, et al. Relationship between energy balance and metabolic profiles in plasma and milk of dairy cows in early lactation[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2020, 103(5): 4795-4805. DOI:10.3168/jds.2019-17777 |

| [33] |

METALLINOU C, ASIMAKOPOULOS B, SCHRÖER A, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ovary[J]. Reprod Sci, 2007, 14(8): 737-749. DOI:10.1177/1933719107310707 |

| [34] |

KAPRARA A, HUHTANIEMI I T. The hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis: Tales of mice and men[J]. Metabolism, 2018, 86: 3-17. DOI:10.1016/j.metabol.2017.11.018 |

| [35] |

WANG H Q, WANG W H, CHEN C Z, et al. Regulation of FSH synthesis by differentially expressed miR-488 in anterior adenohypophyseal cells[J]. Animals (Basel), 2021, 11(11): 3262. |

| [36] |

ROSER J F, MEYERS-BROWN G. Enhancing fertility in mares: recombinant equine gonadotropins[J]. J Equine Vet Sci, 2019, 76: 6-13. DOI:10.1016/j.jevs.2019.03.004 |

| [37] |

SILVA L O E, FOLCHINI N P, ALVES R L O R, et al. Effect of progesterone from corpus luteum, intravaginal implant, or both on luteinizing hormone release, ovulatory response, and subsequent luteal development after gonadotropin-releasing hormone treatment in cows[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2023, 106(6): 4413-4428. DOI:10.3168/jds.2022-22618 |

| [38] |

ZHAO H, GE J B, WEI J C, et al. Effect of FSH on E2/GPR30-mediated mouse oocyte maturation in vitro[J]. Cell Signal, 2020, 66: 109464. DOI:10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109464 |

| [39] |

TANG X R, MA L Z, GUO S, et al. High doses of FSH induce autophagy in bovine ovarian granulosa cells via the AKT/mTOR pathway[J]. Reprod Domest Anim, 2021, 56(2): 324-332. DOI:10.1111/rda.13869 |

| [40] |

LIU Y X, ZHANG Y, LI Y Y, et al. Regulation of follicular development and differentiation by intra-ovarian factors and endocrine hormones[J]. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2019, 24(5): 983-993. DOI:10.2741/4763 |

| [41] |

HUNTER M G, ROBINSON R S, MANN G E, et al. Endocrine and paracrine control of follicular development and ovulation rate in farm species[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2004, 82-83: 461-477. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.013 |

| [42] |

ROCHE J F, MIHM M, DISKIN M G, et al. A review of regulation of follicle growth in cattle[J]. J Anim Sci, 1998, 76(S3): 16-29. |

| [43] |

BUTLER S T, PELTON S H, KNIGHT P G, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone isoforms and plasma concentrations of estradiol and inhibin A in dairy cows with ovulatory and non-ovulatory follicles during the first postpartum follicle wave[J]. Domest Anim Endocrinol, 2008, 35(1): 112-119. DOI:10.1016/j.domaniend.2008.03.002 |

| [44] |

ZHANG J, DENG Y F, CHEN W L, et al. Theca cell-conditioned medium added to in vitro maturation enhances embryo developmental competence of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) oocytes after parthenogenic activation[J]. Reprod Domest Anim, 2020, 55(11): 1501-1510. DOI:10.1111/rda.13799 |

| [45] |

DOMINGUES R R, GINTHER O J, TOLEDO M Z, et al. Increased dietary energy alters follicle dynamics and wave patterns in heifers[J]. Reproduction, 2020, 160(6): 943-953. DOI:10.1530/REP-20-0362 |

| [46] |

PARK S R, KIM S K, KIM S R, et al. Novel roles of luteinizing hormone (LH) in tissue regeneration-associated functions in endometrial stem cells[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2022, 13(7): 605. DOI:10.1038/s41419-022-05054-7 |

| [47] |

FORDE N, BELTMAN M E, LONERGAN P, et al. Oestrous cycles in Bos taurus cattle[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2011, 124(3-4): 163-169. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.08.025 |

| [48] |

MIHM M, GOOD T E M, IRELAND J L H, et al. Decline in serum follicle-stimulating hormone concentrations alters key intrafollicular growth factors involved in selection of the dominant follicle in heifers[J]. Biol Reprod, 1997, 57(6): 1328-1337. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1328 |

| [49] |

PERRY R C, CORAH L R, COCHRAN R C, et al. Influence of dietary energy on follicular development, serum gonadotropins, and first postpartum ovulation in suckled beef cows[J]. J Anim Sci, 1991, 69(9): 3762-3773. DOI:10.2527/1991.6993762x |

| [50] |

SEOANE-COLLAZO P, MARTÍNEZ-SÁNCHEZ N, MILBANK E, et al. Incendiary leptin[J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(2): 472. DOI:10.3390/nu12020472 |

| [51] |

INAGAKI-OHARA K. Gastric leptin and tumorigenesis: beyond obesity[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(11): 2622. DOI:10.3390/ijms20112622 |

| [52] |

NOGUEIRA A V B, NOKHBEHSAIM M, TEKIN S, et al. Resistin is increased in periodontal cells and tissues: in vitro and in vivo studies[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2020, 2020: 9817095. |

| [53] |

SCARAMUZZI R J, BROWN H M, DUPONT J. Nutritional and metabolic mechanisms in the ovary and their role in mediating the effects of diet on folliculogenesis: a perspective[J]. Reprod Domest Anim, 2010, 45(S3): 32-41. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2010.01662.x |

| [54] |

SALEM A M. Variation of leptin during menstrual cycle and its relation to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis: a systematic review[J]. Int J Womens Health, 2021, 13: 445-458. DOI:10.2147/IJWH.S309299 |

| [55] |

CHILDS G V, ODLE A K, MACNICOL M C, et al. The importance of leptin to reproduction[J]. Endocrinology, 2021, 162(2): bqaa204. DOI:10.1210/endocr/bqaa204 |

| [56] |

OHGA H, ITO K, KAKINO K, et al. Leptin is an important endocrine player that directly activates gonadotropic cells in teleost fish, chub mackerel[J]. Cells, 2021, 10(12): 3505. DOI:10.3390/cells10123505 |

| [57] |

DAYI A, BEDIZ C S, MUSAL B, et al. Comparison of leptin levels in serum and follicular fluid during the oestrous cycle in cows[J]. Acta Vet Hung, 2005, 53(4): 457-467. DOI:10.1556/AVet.53.2005.4.6 |

| [58] |

BOELHAUVE M, SINOWATZ F, WOLF E, et al. Maturation of bovine oocytes in the presence of leptin improves development and reduces apoptosis of in vitro-produced blastocysts[J]. Biol Reprod, 2005, 73(4): 737-744. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.105.041103 |

| [59] |

ALSHAHEEN T A, AWAAD M H H, MEHAISEN G M K. Leptin improves the in vitro development of preimplantation rabbit embryos under oxidative stress of cryopreservation[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(2): e0246307. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0246307 |

| [60] |

BISPHAM J, GOPALAKRISHNAN G S, DANDREA J, et al. Maternal endocrine adaptation throughout pregnancy to nutritional manipulation: consequences for maternal plasma leptin and cortisol and the programming of fetal adipose tissue development[J]. Endocrinology, 2003, 144(8): 3575-3585. DOI:10.1210/en.2003-0320 |

| [61] |

MAKAREVICH A V, MARKKULA M. Apoptosis and cell proliferation potential of bovine embryos stimulated with insulin-like growth factor I during in vitro maturation and culture[J]. Biol Reprod, 2002, 66(2): 386-392. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod66.2.386 |

| [62] |

GIBSON C, DE RUIJTER-VILLANI M, STOUT T A E. Insulin-like growth factor system components expressed at the conceptus-maternal interface during the establishment of equine pregnancy[J]. Front Vet Sci, 2022, 9: 912721. DOI:10.3389/fvets.2022.912721 |

| [63] |

GARNSWORTHY P C, SINCLAIR K D, WEBB R. Integration of physiological mechanisms that influence fertility in dairy cows[J]. Animal, 2008, 2(8): 1144-1152. DOI:10.1017/S1751731108002358 |

| [64] |

WOELDERS H, VAN DER LENDE T, KOMMADATH A, et al. Central genomic regulation of the expression of oestrous behaviour in dairy cows: a review[J]. Animal, 2014, 8(5): 754-764. DOI:10.1017/S1751731114000342 |

| [65] |

BAKER J, HARDY M P, ZHOU J, et al. Effects of an Igf1 gene null mutation on mouse reproduction[J]. Mol Endocrinol, 1996, 10(7): 903-918. |

| [66] |

FENWICK M A, LLEWELLYN S, FITZPATRICK R, et al. Negative energy balance in dairy cows is associated with specific changes in IGF-binding protein expression in the oviduct[J]. Reproduction, 2008, 135(1): 63-75. DOI:10.1530/REP-07-0243 |

| [67] |

BUTLER W R. Energy balance relationships with follicular development, ovulation and fertility in postpartum dairy cows[J]. Livest Prod Sci, 2003, 83(2-3): 211-218. DOI:10.1016/S0301-6226(03)00112-X |

| [68] |

KAWASHIMA C, SAKAGUCHI M, SUZUKI T, et al. Metabolic profiles in ovulatory and anovulatory primiparous dairy cows during the first follicular wave postpartum[J]. J Reprod Dev, 2007, 53(1): 113-120. DOI:10.1262/jrd.18105 |

| [69] |

SONG Y X, WANG Z J, ZHAO C, et al. Effect of negative energy balance on plasma metabolites, minerals, hormones, cytokines and ovarian follicular growth rate in Holstein dairy cows[J]. J Vet Res, 2021, 65(3): 361-368. DOI:10.2478/jvetres-2021-0035 |

| [70] |

WARZYCH E, LIPINSKA P. Energy metabolism of follicular environment during oocyte growth and maturation[J]. J Reprod Dev, 2020, 66(1): 1-7. DOI:10.1262/jrd.2019-102 |

| [71] |

ZHANG Z X, LI X, YANG F, et al. DHHC9-mediated GLUT1 S-palmitoylation promotes glioblastoma glycolysis and tumorigenesis[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 5872. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-26180-4 |

| [72] |

KRISHER R L, BAVISTER B D. Enhanced glycolysis after maturation of bovine oocytes in vitro is associated with increased developmental competence[J]. Mol Reprod Dev, 1999, 53(1): 19-26. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199905)53:1<19::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-U |

| [73] |

SUTTON-MCDOWALL M L, GILCHRIST R B, THOMPSON J G. The pivotal role of glucose metabolism in determining oocyte developmental competence[J]. Reproduction, 2010, 139(4): 685-695. DOI:10.1530/REP-09-0345 |

| [74] |

WALSH S W, MATTHEWS D, BROWNE J A, et al. Acute dietary restriction in heifers alters expression of genes regulating exposure and response to gonadotrophins and IGF in dominant follicles[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2012, 133(1-2): 43-51. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.06.012 |

| [75] |

MEGAHED A A, HIEW M W H, CONSTABLE P D. Clinical utility of plasma fructosamine concentration as a hypoglycemic biomarker during early lactation in dairy cattle[J]. J Vet Intern Med, 2018, 32(2): 846-852. DOI:10.1111/jvim.15049 |

| [76] |

BERTEVELLO P S, TEIXEIRA-GOMES A P, SEYER A, et al. Lipid identification and transcriptional analysis of controlling enzymes in bovine ovarian follicle[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018, 19(10): 3261. DOI:10.3390/ijms19103261 |

| [77] |

ABAZARIKIA A, ARIU F, RASEKHI M, et al. Distribution and size of lipid droplets in oocytes recovered from young lamb and adult ovine ovaries[J]. Reprod Fertil Dev, 2020, 32(11): 1022-1026. DOI:10.1071/RD20035 |

| [78] |

MISSIO D, FRITZEN A, VIEIRA C C, et al. Increased β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) concentration affect follicular growth in cattle[J]. Anim Reprod Sci, 2022, 243: 107033. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2022.107033 |

| [79] |

LIU T, QU J X, TIAN M Y, et al. Lipid metabolic process involved in oocyte maturation during folliculogenesis[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 10: 806890. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2022.806890 |

| [80] |

SHI M H, SIRARD M A. Metabolism of fatty acids in follicular cells, oocytes, and blastocysts[J]. Reprod Fertil, 2022, 3(2): R96-R108. DOI:10.1530/RAF-21-0123 |

| [81] |

FURUKAWA E, CHEN Z, KUBO T, et al. Simultaneous free fatty acid elevations and accelerated desaturation in plasma and oocytes in early postpartum dairy cows under intensive feeding management[J]. Theriogenology, 2022, 193: 20-29. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.09.006 |

(编辑 郭云雁)