2. 中国农业科学院北京畜牧兽医研究所, 农业农村部奶产品质量安全风险评估实验室, 北京 100193

2. Laboratory of Quality and Safety Risk Assessment for Dairy Products of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100193, China

奶牛乳房炎有感染性或非感染性之分[1],作为奶牛重要的经济性疾病之一,会导致牛奶产量下降及质量受到影响,对动物福利也是一个问题[2]。奶牛乳房炎大多由葡萄球菌(Staphylococci)、链球菌(Streptococcus)、大肠菌群(coliform)等病原微生物引起[2-3]。在英国,包括大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、乳房链球菌(Streptococcus uberis)、金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)、停乳链球菌(Streptococcus dysgalactiae)和无乳链球菌(Streptococcus agalactiae)在内的五种细菌是引起奶牛乳房炎的常见细菌[4]。Gao等[5]报道,大肠杆菌、克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella)、凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌(coagulase-negative Staphylococci)、停乳链球菌和金黄色葡萄球菌是中国临床型乳房炎最常分离到的细菌。因此,确定主要乳房炎病原微生物及来源,有利于奶牛乳房炎的管理和预防。

生乳中微生物的组成与牧场环境或奶牛感染有关。研究发现,影响生乳的微生物可以从牧场环境中转移,包括牛群健康、养殖环境、养殖人员卫生和饲养方法[6-7]。另有研究表明,垫料[8]、乳头皮肤[7]、奶杯和药浴杯[9]是生乳污染的重要来源。根据Hogan等[10]的研究,垫料类型和日常管理是影响乳房健康和乳房感染及发病率的主要因素。此外,Gao等[5]和Song等[11]都发现,在有效防控奶牛患乳房炎时,中国牧场应注意地区、季节和垫料材料等因素。

关于我国规模性牧场乳房炎主要病原微生物的分布及其与牧场环境之间的关联,多数研究基于培养法进行分析[11]。本研究通过16S rDNA测序对中国天津某牧场的环境和乳房炎乳中微生物种类进行研究,并利用SourceTracker分析探明乳房炎乳细菌的潜在来源,以期为牧场管控提供精准的靶向。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料与试剂无菌生理盐水管(带棉签,北京华威锐科化工有限公司);营养琼脂(北京陆桥技术股份有限公司);营养琼脂斜面(北京陆桥技术股份有限公司);E.Z.N.ATM Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit(美国OMEGA公司);Taq PCR Master Mix[宝日医生物技术(北京)有限公司];PCR引物[生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司];2×HieffⓇ Robust PCR Master Mix(日本TOYOBO公司);SanPrep DNA凝胶提取试剂盒(中国SANGON Biotechnology公司)。

1.2 仪器与设备HPS-250生化培养箱(北京东联哈尔仪器制造有限公司);HDL BSC-136011A2生物安全柜(北京东联哈尔仪器制造有限公司);T100 PCR基因扩增仪(美国BIO-RAD公司);PowerPac电泳仪(美国BIO-RAD公司);Qubit 4.0荧光剂(美国Life Technologies公司);ABI Step One Plus Real-Time PCR(美国Life Technologies公司)。

1.3 方法1.3.1 样品采集 2019年9—11月在天津某牧场对单头病牛乳房炎乳、牧场环境(空气、饮用水、饲料、粪便、垫料、新垫料及喷淋水)和挤奶厅(前药浴液、后药浴液、前药浴杯、后药浴杯、奶杯、乳头皮肤)进行样品采集,共计74份,具体样品信息详见表 1,采样方法详见胡海燕等[12]的报道。

|

|

表 1 试验样品汇总 Table 1 Summary of tested samples |

1.3.2 DNA提取和PCR扩增 用移液枪吸取1 mL液体样品,在营养琼脂平板涂布,36 ℃下恒温培养48 h,之后用20 mL氯化钠(0.85%)清洗每个平板,收集所有的细菌菌落,制备可培养样品。固体样品称取25 g,溶于225 mL氯化钠(0.85%)中,均质1 min后,吸取1 mL液体涂布于营养琼脂平板,36 ℃下恒温培养48 h,之后用20 mL氯化钠(0.85%)清洗每个平板,收集所有的细菌菌落,制备可培养样品。

使用E.Z.N.ATM Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit将所有制备好的可培养样品和非培养样品提取DNA。DNA的完整性和浓度分别通过琼脂糖凝胶电泳和Qubit 4.0荧光剂测量。用于PCR的引物包括V3-V4通用引物341F: CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG和805R: GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC。

1.3.3 16S rDNA扩增子测序 用2%琼脂糖凝胶提取PCR产物,使用SanPrep DNA凝胶提取试剂盒进行纯化。扩增子通过ABI Step One Plus Real-Time PCR进行定量,并在Illumina平台上进行成对末端测序(PE250)。

1.3.4 统计分析 通过CASAVA碱基调用分析,将Illumina MiseqTM获得的原始图像数据文件转换为原始测序读数,并将结果以FASTQ文件格式存储。原始数据首先由PEAR(1.9.3版)进行清洗,以获得高质量的清洁读数[13]。UPARSE(9.2.64版)被用来聚类相似度≥97%的操作分类单元(operational taxonomic unit,OTU)[14]。通过R(3.2版)中的Vegan包(2.0-10版),用Jaccard和bray-curtis距离矩阵计算进行主成分分析(PCA)[15]。QIIME(1.9.1版)被用来计算微生物群的丰富性和多样性[16]。用Mothur(1.30.1版)计算组间的α多样性比较[17]。

1.3.5 SourceTracker进行病原微生物溯源分析 为追溯乳房炎乳微生物的来源,将乳房炎乳定为“池(Sink)”样品,将其他牛舍环境样品和挤奶厅样品设置为“源(Source)”样品。使用基于贝叶斯算法的SourceTracker软件(0.9.8版)确定每个“源”对“池”的贡献程度[18]。数据运行1 000次,其他参数为默认。

2 结果 2.1 16S rDNA测序概述每个样品的原始序列读数为41 190~174 790。清洗后,每个样品的序列读数为8 777~170 415。此外,OTU数为61~5 484。

2.2 α多样性本试验使用了三个指标(Chao1、Shannon和Simpson指数)来分别测量基于培养和非培养样品中微生物组的α多样性。由于喷淋水仅有一份,所以未计算指数s值且未统计差异性。

表 2和表 3分别显示了乳房炎乳和牛舍环境之间以及乳房炎乳和挤奶厅之间可培养样品的α多样性。可培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品细菌群落之间Shannon指数(x±s)和Simpson指数(x±s)存在显著差异(P < 0.05),而可培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的三个指标(Chao1、Shannon和Simpson)间均存在显著差异(P < 0.05),表明可培养的乳房炎乳样品的细菌群落多样性低于其他样品。

|

|

表 2 可培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品的α多样性(x±s) Table 2 Alpha diversity of culture-based samples between mastitis milk and pan barn(x±s) |

|

|

表 3 可培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的α多样性(x±s) Table 3 Alpha diversity of culture-based samples between mastitis milk and parlour(x±s) |

对于可培养样品,挤奶厅中奶杯的Chao1指数最高,其次是乳头皮肤样品,而乳房炎乳样品的Chao1指数在所有样品中最低。此外,新垫料样品的Shannon指数最高,其次是垫料样品,乳房炎乳样品的Shannon指数也是所有样品中最低的。

表 4、5分别展示了乳房炎乳和牛舍环境之间以及乳房炎乳和挤奶厅之间未培养样品的α多样性。未培养的乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品细菌群落之间Chao1指数(x±s)和Shannon指数(x±s)存在显著差异(P < 0.05),而未培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的三个指标(Chao1、Shannon和Simpson)均存在显著差异(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 4 未培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品的α多样性(x±s) Table 4 Alpha diversity of nonculture-based samples between mastitis milk and pan barn(x±s) |

|

|

表 5 未培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的α多样性(x±s) Table 5 Alpha diversity of nonculture-based samples between mastitis milk and parlour(x±s) |

通过高通量16S rDNA基因测序,研究牛舍环境和挤奶厅对乳房炎乳的影响,发现乳房炎乳和牛舍环境未培养样品之间以及乳房炎乳和挤奶厅未培养样品之间细菌群落的α多样性出现显著分离(P < 0.05),分析表明挤奶厅样品中的细菌群落与乳房炎乳细菌群落具有更大的相似性,其可能对乳房炎乳细菌群落产生影响。

2.3 β多样性通过非度量多维排列(non-metric multidimensional scaling,NMDS)指数来区分OTU结果,点与点之间的距离反映了样品之间的差异程度。

对于可培养乳房炎乳样品和牛舍环境样品,新垫料样品和垫料样品的细菌群落最相似,而可培养乳房炎乳样品具有复杂的细菌群落(图 1A)。此外,科水平上的ANOSIM分析显示R值为0.524(P=0.001,图 1B)。

|

A. 细菌OTU多样性概况的非度量多维尺度(NMDS)分析,不同颜色或形状的点代表不同的组,横纵坐标是相对距离;B. ANOSIM,科水平上的相似性分析(R=0.524,P=0.001)。M. 乳房炎乳;F. 粪便;NL. 新垫料;L. 垫料;DW. 饮用水;SW. 喷淋水;Fd. 饲料;A. 空气 A. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analyses of the bacterial OTU diversity profiles. Different color or shape points stand for different groups. Horizontal and vertical coordinates is relative distances, which shows no practical meaning; B. ANOSIM, analysis of similarities on family level (R=0.524, P=0.001). M. Mastitis milk samples; F. Feces samples; NL. New bedding material samples; L. Bedding material samples; DW. Drinking water samples; SW. Spray water sample; Fd. Feed samples; A. Air samples 图 1 可培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品之间的群落差异 Fig. 1 The community difference among the culture-based mastitis milk samples and the pan barn samples |

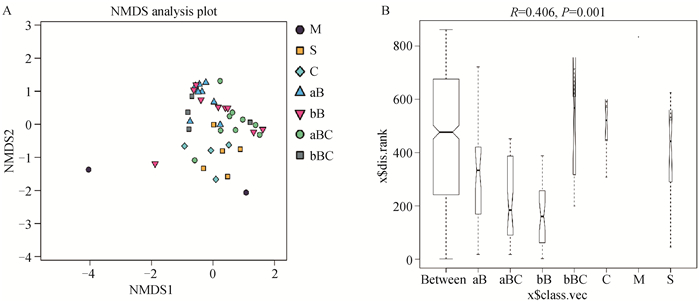

对于可培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品,前药浴液和后药浴液的细菌群落结构相对相似(图 2A),科水平上的ANOSIM分析显示R值为0.406(P=0.001,图 2B)。

|

A. 细菌OTU多样性概况的非度量多维尺度(NMDS)分析,不同颜色或形状的点代表不同的组,横纵坐标是相对距离;B. ANOSIM,科水平上的相似性分析(R=0.406,P=0.001)。M. 乳房炎乳;S. 乳头皮肤;C. 奶杯;aB. 前药浴液;bB. 后药浴液;aBC.前药浴杯;bBC.后药浴杯 A. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analyses of the bacterial OTU diversity profiles. Different color or shape points stand for different groups. Horizontal and vertical coordinates is relative distances, which shows no practical meaning; B. ANOSIM, analysis of similarities on family level (R=0.406, P=0.001). M. Mastitis milk samples; S. Teat skin samples; C. Teat dip cup; aB. Pre teat medicine samples; bB. Post teat medicine samples; aBC. Pre medicine cup samples; bBC. Post medicine cup samples 图 2 可培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品之间的群落差异 Fig. 2 The community difference among the culture-based mastitis milk samples and the parlour samples |

对于未培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品,NMDS分析显示粪便样品、新垫料样品、垫料样品和空气样品中细菌群落相似,而未培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅间的样品之间存在较大差异(图 3A)。科水平上的ANOSIM分析显示R值为0.503(P=0.001,图 3B)。

|

A. 细菌OTU多样性概况的非度量多维尺度(NMDS)分析,不同颜色或形状的点代表不同的组,横纵坐标是相对距离;B. ANOSIM,科水平上的相似性分析(R=0.503,P=0.001)。M. 乳房炎乳;F. 粪便;NL. 新垫料;L. 垫料;DW. 饮用水;SW. 喷淋水;Fd. 饲料;A. 空气 A. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analyses of the bacterial OTU diversity profiles. Different color or shape points stand for different groups. Horizontal and vertical coordinates is relative distances, which shows no practical meaning; B. ANOSIM, analysis of similarities on family level (R=0.503, P=0.001). M. Mastitis milk samples; F. Feces samples; NL. New bedding material samples; L. Bedding material samples; DW. Drinking water samples; SW. Spray water sample; Fd. Feed samples; A. Air samples 图 3 未培养乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品之间的群落差异 Fig. 3 The community difference among the nonculture-based mastitis milk samples and the pan barn samples |

对于未培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品,细菌群落结构差异较小(图 4A),科水平上的ANOSIM分析显示R值为0.361(P=0.001,图 4B)。β多样性分析说明了乳房炎乳和牛舍样品之间以及乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品之间具有差异。

|

A. 细菌OTU多样性概况的非度量多维尺度(NMDS)分析,不同颜色或形状的点代表不同的组,横纵坐标是相对距离;B. ANOSIM,科水平上的相似性分析(R=0.361,P=0.001)。M. 乳房炎乳;S. 乳头皮肤;C. 奶杯;aB. 前药浴液;bB. 后药浴液;aBC. 前药浴杯;bBC. 后药浴杯 A. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analyses of the bacterial OTU diversity profiles. Different color or shape points stand for different groups. Horizontal and vertical coordinates is relative distances, which shows no practical meaning; B. ANOSIM, analysis of similarities on family level (R=0.361, P=0.001). M. Mastitis milk samples; S. Teat skin samples; C. Teat dip cup; aB. Pre teat medicine samples; bB. Post teat medicine samples; aBC. Pre medicine cup samples; bBC. Post medicine cup samples 图 4 未培养乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品之间的群落差异 Fig. 4 The community difference among the nonculture-based mastitis milk samples and the parlour samples |

2.4.1 可培养样品的细菌群落结构 OTU分析一共鉴定出50个不同科的微生物。对于可培养的乳房炎乳样品(cM1~cM6),仅在cM3和cM5样品中发现细菌菌落,而在其他平板上没有生长。样品cM3和cM5样品中的主要细菌分别是肠杆菌科(Enterobacteriaceae,99.87%)和葡萄球菌科(Staphylococcaceae,94.04%)(图 5A)。本试验中在乳房炎乳样品中发现了高比例的不可培养样品,这个结果曾经在中国南方畜群的样品中被报道[5]。

|

A.可培养的乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品的细菌群落结构;B.可培养的乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的细菌群落结构。M. 乳房炎乳;F. 粪便;NL. 新垫料;L. 垫料;DW. 饮用水;SW. 喷淋水;Fd. 饲料;A. 空气;S. 乳头皮肤;C. 奶杯;B1~B9. 前药浴液;B10~B18. 后药浴液;BC1~BC9. 前药浴杯;BC10~BC18. 后药浴杯 A. Microbiota community of cultured-based mastitis samples and pan barn samples; B. Microbiota community of cultured-based mastitis samples and parlour samples. M. Mastitis milk samples; F. Feces samples; NL. New bedding material samples; L. Bedding material samples; DW. Drinking water samples; SW. Spray water sample; Fd. Feed samples; A. Air samples; S. Teat skin samples; C. Teat dip cup; B1-B9. Pre teat medicine samples; B10-B18. Post teat medicine samples; BC1-BC9. Pre medicine cup samples; BC10-BC18. Post medicine cup samples 图 5 可培养样品的细菌群落结构(科水平) Fig. 5 Microbiota community of cultured-based samples at family level |

对于可培养的牛舍环境样品,芽胞杆菌科(Bacillaceae)在饲料样品中的丰度最大(56.69%),其次是饮用水(40.46%)和粪便样品(39.56%);莫拉菌科则在垫料样品中丰度最大(39.59%),其次为新垫料样品(33.32%)和喷淋水样品(6.47%);动球菌科则在空气样品中丰度最高(53.36%,图 5A)。对于可培养的挤奶厅样品,细菌群落表现出高度相似性(图 5B)。芽胞杆菌科是药浴液(cB1~cB18)和药浴杯(cBC1~cBC13)中的优势菌科,占比超过50%;而在部分乳头皮肤样品(cS3和cS5)和奶杯样品(cC1和cC5)中则含有大量的动球菌科细菌。

2.4.2 未培养样品的细菌群落结构 对于未培养的样品,乳房炎乳样品(M1~M6)中的优势细菌(科水平)包括链球菌科(Streptococcaceae)、假单胞菌科(Pseudomonadaceae)、肠杆菌科、伯克霍尔德菌科(Burkholderiaceae)、莫拉菌科、毛单胞菌科(Comamonadaceae)和瘤胃球菌科(Ruminococcaceae)。M1、M2和M3样品中主要细菌分别为链球菌(99.85%)、假单胞菌科(89.05%)和肠杆菌科(99.84%),而M4、M5和M6样品中伯克霍尔德菌科占比较高,分别为14.15%、11.99%和33.25%(图 6A)。

|

A. 未培养的乳房炎乳和牛舍环境样品的细菌群落结构;B. 未培养的乳房炎乳和挤奶厅样品的细菌群落结构。M. 乳房炎乳;F. 粪便;NL. 新垫料;L. 垫料;DW. 饮用水;SW. 喷淋水;Fd. 饲料;A. 空气;S. 乳头皮肤;C. 奶杯;B1~B9. 前药浴液;B10~B18. 后药浴液;BC1~BC9. 前药浴杯;BC10~BC18. 后药浴杯 A. Microbiota community of uncultured-based mastitis samples and pan barn samples; B. Microbiota community of uncultured-based mastitis samples and parlour samples. M. Mastitis milk samples; F. Feces samples; NL. New bedding material samples; L. Bedding material samples; DW. Drinking water samples; SW. Spray water sample; Fd. Feed samples; A. Air samples; S. Teat skin samples; C. Teat dip cup; B1-B9. Pre teat medicine samples; B10-B18. Post teat medicine samples; BC1-BC9. Pre medicine cup samples; BC10-BC18. Post medicine cup samples 图 6 未培养样品的细菌群落结构(科水平) Fig. 6 Microbiota community of uncultured-based samples at family level |

对于未培养的牛舍样品,优势菌科是不同的。瘤胃球菌科(12.44%)的平均丰度最高,其次是莫拉菌科(12.01%)和黄杆菌科(Flavobacteriaceae,8.63%)。然而,不同的样品中的细菌群落不同。在粪便(F1~F6)样品中,瘤胃球菌科细菌比例最高,其次是毛螺菌科(Lachnospiraceae)、卟啉单胞菌科(Porphyromonadaceae)和消化链球菌科(Peptostreptococcaceae)。此外,空气样品(A1~A3)中,莫拉菌科是丰度最高的科,占55%以上,其次是假单胞菌科和根瘤菌科(Rhizobiacea,图 6A)。对于未培养的挤奶厅样品,瘤胃球菌科(12.36%)、莫拉菌科(7.20%)和毛螺菌科(7.00%)的丰度最高。挤奶厅样品中科水平的细菌多样性比较高。前药浴液样品(B1~B9)中莫拉菌科的丰度最高(24.50%),其次是毛螺菌科(7.97%)。然而,后药浴液(B10~B18)中,瘤胃球菌科和莫拉菌科细菌丰度最高,B13样品中芽胞杆菌科数量较多,占38.88%。在前药浴杯(BC1-BC9)和后药浴杯(BC10~BC18)样品,瘤胃球菌科和伯克霍尔德菌科的丰度更高(图 6B)。

2.5 使用SourceTracker进行源头分析在本研究中,利用SourceTracker分析未培养的乳房炎乳中细菌的潜在来源(图 7)。其中,乳头皮肤中细菌与乳房炎乳中细菌的相似性较高,为19.06%,其次是空气(15.47%)、药浴杯(14.43%)和粪便(10.36%)。此外,仍有部分乳房炎乳中细菌来源不明,因此,需要开展进一步的研究,以确定病原微生物的最可能来源,从源头降低污染。

|

图 7 乳房炎乳中病原微生物的不同来源贡献率 Fig. 7 Pie charts of the percentages of inferred sources of mastitis milk microbiota |

本研究旨在通过高通量16S rDNA基因测序,探讨牛舍环境及挤奶厅对奶牛乳房炎的影响。此外,α多样性表明了牛舍环境和乳房炎乳样品之间以及挤奶厅和乳房炎乳样品之间的细菌存在显著差异(P < 0.05)。此外,β多样性分析表明了来自牛舍环境样品的细菌群落与挤奶厅样品的细菌群落之间差异。

与之前使用传统方法比较乳房炎细菌与农场环境之间关联的研究相反[5, 11],作者不仅关注平板可培养的细菌多样性,还关注非培养样品中的细菌多样性。本研究表明样品中的微生物群存在差异,一些样本明显以一个属为主,而另一些样本则表现出多样化的特征。在乳房炎乳样本中发现了阴性培养样本,这些样本也存在于中国南方的畜群中[5]。芽胞杆菌科I、动球菌科和莫拉菌科是可培养的牛舍环境和挤奶厅样品中最主要的科,尤其是在药浴液和药浴杯中。Fursova等[19]发现患病动物中的芽胞杆菌科增加,但动球菌科的百分比下降。动球菌科是健康奶牛和牛肠道中的主要细菌,因此可能是粪便细菌中的主要菌群[20-21]。Nguyen等[22]发现莫拉菌科和动球菌科是垫料和空气尘埃微生物群中排名前20的细菌类群,并且两者的相对丰度都呈季节性变化(夏季>冬季)。

分类结果表明,肠杆菌科是本试验中可培养和未培养乳房炎乳样品M3的优势菌科。然而,乳房炎乳样品M5中的优势菌科不同,分别是可培养样品中的葡萄球菌科和未培养样品中的伯克霍尔德菌科。尽管不同国家和地区乳房炎乳中病原微生物的优势菌群存在差异,但本研究结果与Fursova等[19]的结果一致。他们在俄罗斯中部的动物乳房炎乳中检测到假单胞菌科、伯克霍尔德菌科以及链球菌科、葡萄球菌科和芽胞杆菌科。Bi等[23]发现金黄色葡萄球菌、大肠杆菌、无乳链球菌、停乳链球菌、克雷伯菌、黏质沙雷菌(Serratia marcescens)和化脓性弧菌(Vibrio pyogenes)是中国奶牛群中常见的乳房炎病原微生物。此外,很多研究也关注了伯克霍尔德菌科在人类和动物乳房炎乳中的变化。与人类亚急性乳房炎和健康乳房相比,急性乳房炎乳样品中的气单胞菌科(Aeromonadaceae)、伯克霍尔德菌科、布鲁氏菌科(Brucellaceae)和链球菌科的水平显著更高[24]。Gámez-Valdez等[25]发现伯克霍尔德菌科在母乳样品中的相对丰度平均值更高[9.0%±11.7% (0% ~48.6%范围)]。此外,在第5周哺乳期母乳中伯克霍尔德菌科的相对丰度较高且值非常高[26]。

总体而言,未培养样品中的细菌群落组成更为丰富。瘤胃球菌科是所有粪便样品和很多药浴液样品中丰度最高的菌科,这与其他研究一致。Nguyen等[22]报道瘤胃球菌科(34.1%)、拟杆菌科(Bacteroidaceae,10.2%)、毛螺菌科(9.6%)、理菌科(Rikenellaceae,3.3%)和梭菌科(Clostridiaceae,2.9%)是粪便中丰富最高的五个菌科,并且与季节无关。此外,瘤胃球菌科也是夏季和冬季垫料样品细菌群落中丰度最高的五个分类群之一。Wu等[8]也证明瘤胃球菌科是典型的粪便细菌类群。瘤胃球菌科已被证明与牛乳房炎显著相关[27]。

莫拉菌科是空气样品中丰度最高的科,其可引起人类呼吸系统疾病[28]。莫拉菌科在空气灰尘中的细菌群落中排名第二,在垫料细菌群落中排名第三[22]。此外,莫拉菌科在牛奶样品、垫料样品、沙土样品、稻壳样品和被用作奶牛垫料的粪便堆肥样品中均存在[29]。虽然只有一个喷淋水样品,但其中细菌群落丰度最高的是毛单胞菌科,这与其他样品完全不同。毛单胞菌科广泛存在于淡水生境中[30]。Rault等[31]报道称,在健康的乳头细菌群落中发现了毛单胞菌科。然而毛单胞菌科不是与乳房炎相关的病原体[32],并且在不同的感染状态间存在差异[33]。

高通量宏基因组学结合SourceTracker算法已被用于追溯不同环境中细菌群落的变化[18],这可能有助于阐明细菌群落从环境到奶牛的传播[7]。在本研究中,作者发现乳头皮肤、空气、药浴杯和粪便是乳房炎乳细菌群落的主要贡献者。本研究与Verdier-Metz等[34]一致,他们发现乳头皮肤是生乳细菌群落的来源。Doyle等[35]还发现乳头皮肤是生乳细菌群落的最大贡献者,其次是粪便,这表明生乳细菌群落受牧场管理的影响。此外,Wu等[8]发现牛奶细菌群落与空气中的细菌群落有关,而Du等[9]研究表明药浴杯和奶杯是生乳中微生物的最重要贡献者。

4 结论本研究通过16S rDNA测序结合SourceTracker分析了乳房炎乳中细菌群落与牛舍环境和挤奶厅样品中细菌群落的相似性,这将对阐明乳房炎乳细菌群落与牛舍环境和挤奶厅细菌群落的关系奠定了基础。本研究发现挤奶厅样品,尤其是乳头皮肤,对乳房炎乳细菌群落结构有影响,因此,应当进一步加强挤奶厅的卫生管理与操作规范,从源头降低乳及乳制品中微生物引起的质量与安全风险。

| [1] |

BRADLEY A J. Bovine mastitis: an evolving disease[J]. Vet J, 2002, 164(2): 116-128. DOI:10.1053/tvjl.2002.0724 |

| [2] |

HEIKKILÄ A M, LISKI E, PYÖRÄLÄ S, et al. Pathogen-specific production losses in bovine mastitis[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2018, 101(10): 9493-9504. DOI:10.3168/jds.2018-14824 |

| [3] |

RUEGG P L. A 100-year review: mastitis detection, management, and prevention[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2017, 100(12): 10381-10397. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13023 |

| [4] |

ANON. Veterinary investigation surveillance report[R]. London: Veterinary Laboratories Agency, 2001.

|

| [5] |

GAO J, BARKEMA H W, ZHANG L M, et al. Incidence of clinical mastitis and distribution of pathogens on large Chinese dairy farms[J]. J Dairy Sci, 2017, 100(6): 4797-4806. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-12334 |

| [6] |

VACHEYROU M, NORMAND A C, GUYOT P, et al. Cultivable microbial communities in raw cow milk and potential transfers from stables of sixteen French farms[J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2011, 146(3): 253-262. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.02.033 |

| [7] |

DOYLE C J, GLEESON D, O'TOOLE P W, et al. Impacts of seasonal housing and teat preparation on raw milk microbiota: a high-throughput sequencing study[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2017, 83(2): e02694-16. |

| [8] |

WU H M, NGUYEN Q D, TRAN T T M, et al. Rumen fluid, feces, milk, water, feed, airborne dust, and bedding microbiota in dairy farms managed by automatic milking systems[J]. Anim Sci J, 2019, 90(3): 445-452. DOI:10.1111/asj.13175 |

| [9] |

DU B Y, MENG L, LIU H M, et al. Impacts of milking and housing environment on milk microbiota[J]. Animals (Basel), 2020, 10(12): 2339. |

| [10] |

HOGAN J S, SMITH K L, HOBLET K H, et al. Bacterial counts in bedding materials used on nine commercial dairies[J]. J Dairy Sci, 1989, 72(1): 250-258. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79103-7 |

| [11] |

SONG X B, HUANG X P, XU H Y, et al. The prevalence of pathogens causing bovine mastitis and their associated risk factors in 15 large dairy farms in China: an observational study[J]. Vet Microbiol, 2020, 247: 108757. DOI:10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108757 |

| [12] |

胡海燕, 刘慧敏, 孟璐, 等. 天津某牧场奶牛乳房炎奶样与环境中细菌的分离与鉴定[J]. 中国农业大学学报, 2021, 26(3): 69-79. HU H Y, LIU H M, MENG L, et al. Isolation and identification of mastitic milk and environment bacteria in a dairy farm in Tianjin[J]. Journal of China Agricultural University, 2021, 26(3): 69-79. (in Chinese) |

| [13] |

ZHANG J J, KOBERT K, FLOURI T, et al. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR[J]. Bioinformatics, 2014, 30(5): 614-620. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt593 |

| [14] |

EDGAR R C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads[J]. Nat Methods, 2013, 10(10): 996-998. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.2604 |

| [15] |

OKSANEN J, BLANCHET F G, KINDT R, et al. Vegan community ecology package: ordination methods, diversity analysis and other functions for community and vegetation ecologists[J]. R Package Ver, 2015, 2-3. |

| [16] |

CAPORASO J G, KUCZYNSKI J, STOMBAUGH J, et al. QⅡME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data[J]. Nat Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

| [17] |

SCHLOSS P D, WESTCOTT S L, RYABIN T, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2009, 75(23): 7537-7541. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01541-09 |

| [18] |

KNIGHTS D, KUCZYNSKI J, CHARLSON E S, et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking[J]. Nat Methods, 2011, 8(9): 761-763. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.1650 |

| [19] |

FURSOVA K K, SOKOLOV S L, SHCHANNIKOVA M P, et al. Changes in the microbiome of milk in cows with mastitis[J]. Dokl Biochem Biophys, 2021, 497(1): 75-80. DOI:10.1134/S1607672921020046 |

| [20] |

GANDA E K, BISINOTTO R S, LIMA S F, et al. Longitudinal metagenomic profiling of bovine milk to assess the impact of intramammary treatment using a third-generation cephalosporin[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 37565. DOI:10.1038/srep37565 |

| [21] |

KORSAK N, TAMINIAU B, HUPPERTS C, et al. Assessment of bacterial superficial contamination in classical or ritually slaughtered cattle using metagenetics and microbiological analysis[J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2017, 247: 79-86. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.10.013 |

| [22] |

NGUYEN T T, WU H M, NISHINO N. An investigation of seasonal variations in the microbiota of milk, feces, bedding, and airborne dust[J]. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci, 2020, 33(11): 1858-1865. DOI:10.5713/ajas.19.0506 |

| [23] |

BI Y L, WANG Y J, QIN Y, et al. Prevalence of bovine mastitis pathogens in bulk tank milk in China[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(5): e0155621. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0155621 |

| [24] |

PATEL S H, VAIDYA Y H, PATEL R J, et al. Culture independent assessment of human milk microbial community in lactational mastitis[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 7804. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-08451-7 |

| [25] |

GÁMEZ-VALDEZ J S, GARCÍA-MAZCORRO J F, RINCÓN A H M, et al. Compositional analysis of the bacterial community in colostrum samples from women with gestational diabetes mellitus and obesity[J]. Res Square, 2020. |

| [26] |

MARIN-GÓMEZ W, GRANDE M J, PÉREZ-PULIDO R, et al. Changes in the bacterial diversity of human milk during late lactation period (weeks 21 to 48)[J]. Foods, 2020, 9(9): 1184. DOI:10.3390/foods9091184 |

| [27] |

MA C, SUN Z, ZENG B H, et al. Cow-to-mouse fecal transplantations suggest intestinal microbiome as one cause of mastitis[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6(1): 200. DOI:10.1186/s40168-018-0578-1 |

| [28] |

LIU H Y, LI C X, LIANG Z Y, et al. Moraxellaceae and Moraxella interact with the altered airway mycobiome in asthma[J]. bioRxiv, 2019, 525113. |

| [29] |

WU H M, WANG Y, DONG L, et al. Microbial characteristics and safety of dairy manure ComPosting for reuse as dairy bedding[J]. Biology (Basel), 2020, 10(1): 13. |

| [30] |

MOON K, KANG I, KIM S, et al. Genomic and ecological study of two distinctive freshwater bacteriophages infecting a Comamonadaceae bacterium[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 7989. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-26363-y |

| [31] |

RAULT L, LÉVÊQUE P A, BARBEY S, et al. Bovine teat cistern microbiota composition and richness are associated with the immune and microbial responses during transition to once-daily milking[J]. Front Microbiol, 2020, 11: 602404. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2020.602404 |

| [32] |

NGUYEN Q D, TSURUTA T, NISHINO N. Examination of milk microbiota, fecal microbiota, and blood metabolites of Jersey cows in cool and hot seasons[J]. Anim Sci J, 2020, 91(1): e13441. DOI:10.1111/asj.13441 |

| [33] |

ANDREWS T, NEHER D A, WEICHT T R, et al. Mammary microbiome of lactating organic dairy cows varies by time, tissue site, and infection status[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(11): e0225001. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0225001 |

| [34] |

VERDIER-METZ I, GAGNE G, BORNES S, et al. Cow teat skin, a potential source of diverse microbial populations for cheese production[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2012, 78(2): 326-333. DOI:10.1128/AEM.06229-11 |

| [35] |

DOYLE C J, O'TOOLE P W, COTTER P D. Metagenome-based surveillance and diagnostic approaches to studying the microbial ecology of food production and processing environments[J]. Environ Microbiol, 2017, 19(11): 4382-4391. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13859 |

(编辑 白永平)