2. 江苏高校动物重要疫病与人兽共患病防控协同创新中心, 扬州 225009;

3. 江苏省南通市动物疫病预防控制中心, 南通 226011

2. Jiangsu Co-innovation Center for Prevention and Control of Important Animal Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Yangzhou 225009, China;

3. Nantong Animal Disease Prevention and Control Center, Nantong 226011, China

镉是环境中常见的重金属污染物,可经皮肤、消化道和呼吸道进入人、畜体内。进入机体内的镉排泄率极低,其生物半衰期长达10~30年。脑是镉毒性作用的重要靶器官之一,镉可增加血脑屏障通透性并进入大脑[1]。本实验室前期研究发现,镉可在大鼠大脑皮质内蓄积[2]。大量研究表明,镉可造成人和动物神经系统功能障碍[3-5]。镉致神经系统毒性机制主要包括诱导氧化应激、凋亡和自噬[6-7]。其中,细胞凋亡是镉致神经毒性的重要机制之一。

细胞凋亡是由基因调控的一种细胞程序性死亡,在调节细胞稳态和多细胞生物发育过程中起着重要作用。Fas是肿瘤坏死因子受体超家族的一员,通过与其配体FasL结合在多种细胞凋亡中发挥关键作用[8-10]。当细胞受到凋亡刺激时,FasL与Fas结合,并通过进一步与Fas相关死亡结构域蛋白(FADD)结合,激活半胱氨酸蛋白酶-8(caspase-8),引起细胞凋亡[11];另外,活化的caspase-8可剪切BH3相互作用域死亡激动剂(BID),诱导线粒体释放细胞色素C(Cyt C),介导线粒体凋亡通路[12]。

本实验室前期研究发现镉可通过激活Fas/FasL通路和线粒体通路诱导神经细胞凋亡[13-14]。但是,这两条通路之间的关系以及Fas在镉致神经细胞凋亡线粒体通路中的作用和调控机制尚未完全阐明。本试验以Fas基因沉默的大鼠肾上腺嗜铬细胞瘤细胞(PC12)为模型,用镉进行处理,通过Western blot、免疫荧光染色等方法探究Fas在镉致PC12细胞凋亡中的作用及其对线粒体通路的调控机制,为揭示镉的神经毒性机制提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 细胞PC12细胞购自中国科学院上海生命科学研究院细胞库。Fas基因沉默PC12细胞株(Fas shRNA组,靶序列:5′-GATCCGGTGCGTGTCAAGCT TTAATCTTCAAGAGAGATTAAAGCTTGACA CGCACCTTTTTTA-3′)和插入非特异性序列的对照细胞株(NC组)由实验室构建筛选获得。

1.2 主要试剂与仪器RPMI 1640、马血清和胎牛血清购自Life Technologies公司;L-谷氨酰胺和青链霉素购自BBI公司;醋酸镉和L-多聚赖氨酸购自Sigma公司;细胞线粒体分离试剂盒、Cy 3标记山羊抗兔荧光二抗和DAPI染色液购自碧云天生物技术研究所;凋亡诱导因子(AIF)和核酸内切酶G(Endo G)兔多克隆抗体购自Abcam公司;Bcl-2相关X蛋白(Bax)、B细胞淋巴瘤/白血病-2基因(Bcl-2)、Cyt C、细胞色素C氧化酶亚基Ⅳ(COX-Ⅳ)、活化半胱氨酸蛋白酶-9(cleaved caspase-9)、活化半胱氨酸蛋白酶-3(cleaved caspase-3)、活化多聚二磷酸腺苷核糖聚合酶(cleaved PARP)、β-actin兔单克隆抗体和辣根过氧化物酶标记山羊抗兔二抗购自CST公司;BID兔多克隆抗体购自Novus公司;其余试剂均为国产分析纯。

二氧化碳培养箱购自美国Thermo公司;5810R型低温高速冷冻离心机购自德国Eppendorf公司;电泳仪、转膜仪购自美国BIORAD公司;激光共聚焦显微镜购自德国Leica公司。

1.3 细胞的培养与处理Fas基因沉默的PC12细胞株和对照细胞株接种于RPMI 1640培养基(含10%马血清、5%胎牛血清、1%L-谷氨酰胺、1%青链霉素),置于37 ℃和5% CO2环境的培养箱中培养,当细胞生长状态良好且处于对数生长期时,用10 μmol·L-1 Cd处理细胞12 h,分别命名为对照组(NC组)、镉组(Cd组)、Fas shRNA干扰组(Fas shRNA组)、Fas shRNA与镉共处理组(Fas shRNA+Cd组)。

1.4 细胞总蛋白、胞浆蛋白和线粒体蛋白的提取收集各组细胞,加入适量含有蛋白酶抑制剂的细胞裂解液,冰上裂解30 min,超声裂解20 s;4 ℃,12 000 g·min-1离心10 min,收集上清即为总蛋白。

收集各组细胞,加入适量含有蛋白酶抑制剂的线粒体分离试剂重悬细胞团块,将细胞悬液转移至预冷的玻璃匀浆器中,冰上研磨,随后将匀浆转移至预冷的离心管,4 ℃,600 g·min-1离心10 min,吸取上清至新的离心管,4 ℃,11 000 g·min-1离心10 min,收集上清即为细胞浆蛋白,沉淀为线粒体;向沉淀中加入适量含有蛋白酶抑制剂的线粒体裂解液,冰上裂解30 min,12 000 g·min-1离心10 min,收集上清即为线粒体蛋白。

使用BCA法测定蛋白浓度并将蛋白浓度调整一致,按照1∶4加入5 × SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer,沸水煮10 min,蛋白保存于-80 ℃备用。

1.5 Western blot检测相关蛋白的表达取等量样品进行SDS-PAGE电泳,转印至PVDF膜上,5%脱脂乳室温封闭1 h,4 ℃孵育相应一抗(BID、Bax、Bcl-2、Cyt C、cleaved caspase-9、cleaved caspase-3、cleaved PARP、AIF、Endo G、β-actin、COX-Ⅳ抗体按1∶1 000稀释)过夜,室温孵育二抗(按1∶10 000稀释)1 h,ECL显影检测蛋白表达情况。使用Image J软件分析条带灰度值,目的蛋白与β-actin或COX-Ⅳ灰度值的比值即为目的蛋白的相对表达水平。

1.6 免疫荧光染色检测AIF核转位用0.01% L-多聚赖氨酸包被爬片并将其置于24孔培养板中,将Fas shRNA组和NC组细胞接种于爬片,待其长至对数生长期时,用10 μmol·L-1 Cd处理细胞12 h后,弃去培养基,磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)洗涤2次;4%多聚甲醛固定细胞30 min,弃去固定液,PBS洗涤3次;加入0.5% 曲拉通X-100,室温透膜20 min,PBS洗涤3次;加入5% 牛血清白蛋白,室温封闭1.5 h,弃去封闭液;4 ℃孵育AIF抗体(1∶100)过夜,PBS洗涤3次;室温避光孵育Cy 3标记山羊抗兔荧光二抗(1∶200)1 h,PBS洗涤3次;滴加DAPI染色液,室温避光孵育5 min,PBS洗涤2次;封片,激光共聚焦显微镜观察并拍照。

1.7 数据分析数据采用SPSS 22.0统计软件进行单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVA),再经LSD及Dunnett法进行多重比较,统计结果以“x±s”表示。P < 0.05表示差异显著,P < 0.01表示差异极显著。

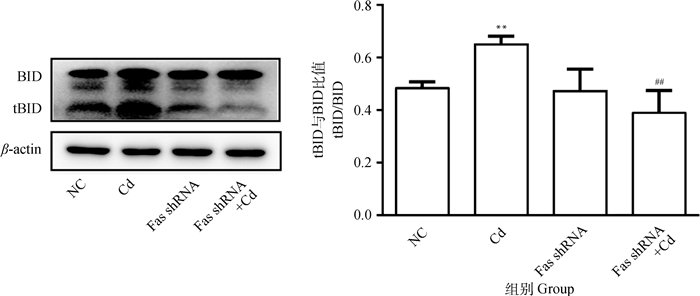

2 结果 2.1 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞BID活化的影响10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,Western blot检测BID和tBID蛋白表达水平。结果如图 1所示,与NC组相比,Cd组tBID/BID比值极显著升高(P < 0.01);与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组tBID/BID比值极显著降低(P < 0.01)。

|

与NC组相比,**表示P < 0.01;与Cd组相比,#表示P < 0.05,##表示P < 0.01。下同 Compared with NC group, ** indicates P < 0.01; Compared with Cd group, # indicates P < 0.05, ## indicates P < 0.01.The same as follows 图 1 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞BID活化的影响 Fig. 1 Effects of Fas silencing on the activation of BID in PC12 cells caused by cadmium |

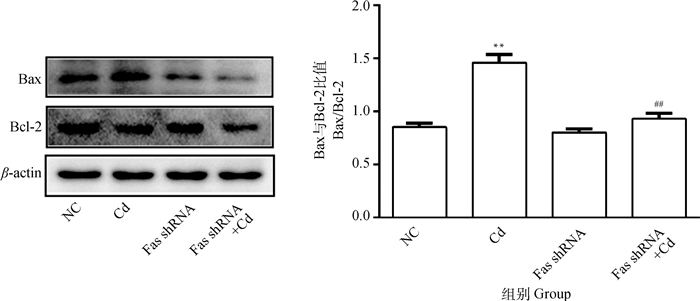

10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,Western blot检测Bax和Bcl-2蛋白表达水平。结果如图 2所示,与NC组相比,Cd组Bax/Bcl-2比值极显著升高(P < 0.01);与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组Bax/Bcl-2比值极显著降低(P < 0.01)。

|

图 2 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞Bax/Bcl-2比值变化的影响 Fig. 2 Effects of Fas silencing on the change of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio in PC12 cells caused by cadmium |

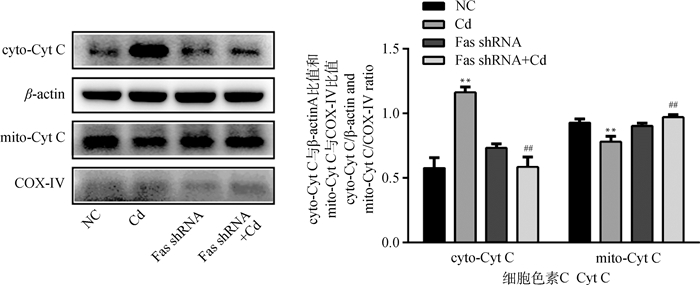

10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,Western blot检测Cyt C在细胞内分布情况。结果如图 3所示,与NC组相比,Cd组线粒体中Cyt C表达量极显著降低(P < 0.01),细胞质中Cyt C表达量极显著升高(P < 0.01);与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组线粒体中Cyt C表达量极显著升高(P < 0.01),细胞质中Cyt C表达量极显著降低(P < 0.01)。

|

图 3 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞Cyt C释放的影响 Fig. 3 Effects of Fas silencing on the release of Cyt C in PC12 cells caused by cadmium |

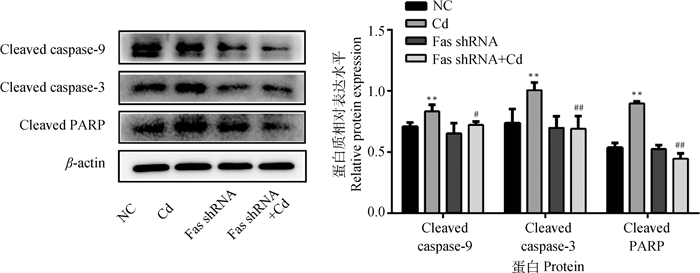

10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,Western blot检测caspase-9、caspase-3和PARP蛋白活化情况。结果如图 4所示,与NC组相比,Cd组Cleaved caspase-9、Cleaved caspase-3和Cleaved PARP蛋白水平均极显著升高(P < 0.01);与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组Cleaved caspase-9蛋白水平显著降低(P < 0.05),Cleaved caspase-3和Cleaved PARP蛋白水平极显著降低(P < 0.01)。

|

图 4 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞caspase-9、caspase-3和PARP蛋白活化的影响 Fig. 4 Effects of Fas silencing on the activation of caspase-9, caspase-3 and PARP in PC12 cells caused by cadmium |

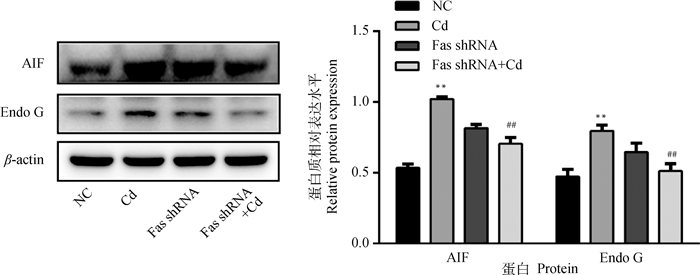

10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,Western blot检测AIF和Endo G蛋白表达水平。结果如图 5所示,与NC组相比,Cd组AIF和Endo G蛋白水平极显著升高(P < 0.01);与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组AIF和Endo G蛋白水平极显著降低(P < 0.01)。

|

图 5 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞AIF和Endo G蛋白表达的影响 Fig. 5 Effects of Fas silencing on the expression of AIF and Endo G in PC12 cells caused by cadmium |

10 μmol·L-1 Cd分别处理NC组和Fas shRNA组细胞12 h,免疫荧光染色法检测AIF核转位情况。结果如图 6所示,与NC组相比,Cd组荧光标记蛋白AIF主要集中于细胞核;与Cd组相比,Fas shRNA+Cd组荧光标记蛋白AIF主要分散于细胞质。

|

红色荧光代表AIF,蓝色荧光代表细胞核 The red puncta represent AIF and the blue puncta represent nuclei 图 6 Fas基因沉默对镉致PC12细胞AIF核转位的影响(标尺=20 μm) Fig. 6 Effects of Fas silencing on the nuclear transposition of AIF in PC12 cells caused by cadmium (scale bar=20 μm) |

细胞凋亡是由基因调控的程序性死亡,重金属镉可诱导包括神经细胞在内的多种细胞发生凋亡[6, 15-16]。死亡受体通路是经典凋亡通路之一,其中,Fas/FasL信号通路备受关注。Fas/FasL信号通路主要通过Fas/FasL/FADD/caspase-8途径介导细胞发生凋亡。体内外研究表明,镉可激活Fas/FasL信号通路诱发神经细胞凋亡[13, 17]。抑制Fas/FasL信号通路中的关键蛋白,能够对细胞凋亡起到一定抑制作用。Ullah等[18]研究发现,抑制Fas能够降低脑缺血导致的细胞凋亡。Zhang等[19]研究发现,干扰Fas显著抑制氧糖剥夺再灌注诱导的人神经母细胞瘤细胞凋亡。本实验室前期研究发现,利用Anti-FasL抑制FasL可减轻镉导致的PC12细胞凋亡[20]。

线粒体在哺乳动物细胞凋亡过程中发挥重要作用。线粒体功能障碍会导致活性氧积累,引起氧化应激和凋亡[21]。线粒体凋亡通路主要由Bcl-2家族蛋白介导。当各种凋亡刺激作用于线粒体时,会激活Bcl-2家族促凋亡成员,导致促凋亡和抗凋亡蛋白的失衡,从而影响线粒体膜通透性[22-23],导致线粒体释放Cyt C等各种促凋亡因子[24-25]。释放的Cyt C与凋亡蛋白酶活化因子-1(Apaf-1)结合形成复合物,激活caspase-9,进而激活caspase-3[26]。激活的caspase-3剪切PARP,抑制受损DNA的修复,促进凋亡细胞死亡[27-28]。体内外研究表明,镉可激活线粒体通路诱发神经细胞凋亡[17, 29]。另外,线粒体通路和Fas/FasL通路之间存在紧密联系,Fas/FasL通路激活的caspase-8将BID剪切为tBID,tBID转位到线粒体,诱导Cyt C释放,从而激活线粒体通路[12]。Yu等[30]研究发现,在小鼠脊髓损伤模型中,Fas缺陷抑制BID、caspase-9和caspase-3的激活,增加抗凋亡蛋白Bcl-2和Bcl-xL的表达。Zhang等[19]研究发现,干扰Fas能够抑制氧糖剥夺再灌注导致的人神经母细胞瘤细胞Bax和Caspase-3上调及Bcl-2下调。本研究结果显示,Fas基因沉默能够显著或极显著抑制镉引起的PC12细胞tBID/BID比值和Bax/Bcl-2比值升高,Cyt C释放,caspase-9、caspase-3和PARP蛋白活化。说明Fas通过调控caspase依赖的线粒体通路参与镉致PC12细胞凋亡。

AIF和Endo G是位于线粒体膜间隙的核酸酶,凋亡发生时被释放到细胞质中并转位到细胞核,通过caspase非依赖途径介导细胞凋亡[31-33]。大量研究表明,在细胞凋亡过程中,Fas可诱导AIF和Endo G从线粒体释放到细胞质或细胞核中[32, 34-35]。Yu等[30]研究发现,在小鼠脊髓损伤模型中,Fas缺陷抑制AIF从线粒体转位到细胞核。本研究结果显示,Fas基因沉默能够极显著抑制镉引起的AIF和Endo G蛋白表达升高,并抑制AIF核转位。说明Fas通过调控caspase非依赖的线粒体通路参与镉致PC12细胞凋亡。

4 结论镉通过激活线粒体通路诱导PC12细胞凋亡,干扰Fas能够抑制镉激活的线粒体凋亡通路,说明Fas通过调控线粒体通路参与镉致PC12细胞凋亡;这为揭示镉的神经毒性机制提供了新的理论基础。

| [1] | WANG B, DU Y L. Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2013, 2013: 898034. |

| [2] | YUAN Y, YANG J L, CHEN J, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid protects against cadmium-induced neuronal injury by inhibiting the endoplasmic reticulum stress eIF2α-ATF4 pathway in rat cortical neurons in vitro and in vivo[J]. Toxicology, 2019, 414: 1–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.tox.2018.12.005 |

| [3] | ANDERSSON H, PETERSSON-GRAWÉ K, LINDQVIST E, et al. Low-level cadmium exposure of lactating rats causes alterations in brain serotonin levels in the offspring[J]. Neurotoxicol Teratol, 1997, 19(2): 105–115. DOI: 10.1016/S0892-0362(96)00218-8 |

| [4] | MIN J Y, MIN K B. Blood cadmium levels and Alzheimer's disease mortality risk in older US adults[J]. Environ Health, 2016, 15(1): 69. DOI: 10.1186/s12940-016-0155-7 |

| [5] | HALDER S, KAR R, CHAKRABORTY S, et al. Cadmium level in brain correlates with memory impairment in F1 and F2 generation mice: improvement with quercetin[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2019, 26(10): 9632–9639. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-019-04283-2 |

| [6] | YUAN Y, BIAN J C, LIU X Z, et al. Oxidative stress and apoptotic changes of rat cerebral cortical neurons exposed to cadmium in vitro[J]. Biomed Environ Sci, 2012, 25(2): 172–181. |

| [7] | TANG K K, LIU X Y, WANG Z Y, et al. Trehalose alleviates cadmium-induced brain damage by ameliorating oxidative stress, autophagy inhibition, and apoptosis[J]. Metallomics, 2019, 11(12): 2043–2051. DOI: 10.1039/C9MT00227H |

| [8] | LIU W, XU C, ZHAO H Y, et al. Osteoprotegerin induces apoptosis of osteoclasts and osteoclast precursor cells via the Fas/Fas ligand pathway[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(11): e0142519. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142519 |

| [9] | HE X Y, WU J, YUAN L Y, et al. Lead induces apoptosis in mouse TM3 Leydig cells through the Fas/FasL death receptor pathway[J]. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2017, 56: 99–105. DOI: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.08.034 |

| [10] | LIU G, YUAN Y, LONG M F, et al. Beclin-1-mediated autophagy protects against cadmium-activated apoptosis via the Fas/Fasl pathway in primary rat proximal tubular cell culture[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 977. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-00997-w |

| [11] | NAGATA S. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis[J]. Annu Rev Genet, 1999, 33: 29–55. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.29 |

| [12] | LUO X, BUDIHARDJO I, ZOU H, et al. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors[J]. Cell, 1998, 94(4): 481–490. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81589-5 |

| [13] |

张雅静. Fas/FasL信号转导通路在镉致神经细胞凋亡中的作用及NAC的保护效应[D]. 扬州: 扬州大学, 2016.

ZHANG Y J. Role of Fas/FasL signaling pathway in cadmium induced neural apoptosis and protrct effect of NAC[D]. Yangzhou: Yangzhou University, 2016. (in Chinses) |

| [14] |

徐卉. 镉致大鼠大脑皮质神经元凋亡的线粒体途径[D]. 扬州: 扬州大学, 2013.

XU H. Mitochondrial pathway of cadmium-induced apoptosis in primary rat cerebral cortical neurons culture[D]. Yangzhou: Yangzhou University, 2013. (in Chinses) |

| [15] | LIU W, XU C, RAN D, et al. CaMKⅡ mediates cadmium induced apoptosis in rat primary osteoblasts through MAPK activation and endoplasmic reticulum stress[J]. Toxicology, 2018, 406-407: 70–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.tox.2018.06.002 |

| [16] | WANG S S, REN X M, HU X D, et al. Cadmium-induced apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress and the JNK signaling pathway in TM3 cells, a model of mouse Leydig cells[J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2019, 368: 37–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.taap.2019.02.012 |

| [17] |

赵世文. α-硫辛酸对铅镉联合致大鼠大脑皮质毒性损伤的保护效应[D]. 扬州: 扬州大学, 2018.

ZHAO S W. The protective effects of α-lipoid-acid on toxic damage of cadmium and lead exposure in cerebral cortex of rats[D]. Yangzhou: Yangzhou University, 2018. (in Chinses) |

| [18] | ULLAH I, CHUNG K, OH J, et al. Intranasal delivery of a Fas-blocking peptide attenuates Fas-mediated apoptosis in brain ischemia[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 15041. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-33296-z |

| [19] | ZHANG J F, SHI L L, ZHANG L, et al. MicroRNA-25 negatively regulates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced cell apoptosis through Fas/FasL pathway[J]. J Mol Neurosci, 2016, 58(4): 507–516. DOI: 10.1007/s12031-016-0712-0 |

| [20] | YUAN Y, ZHANG Y J, ZHAO S W, et al. Cadmium-induced apoptosis in neuronal cells is mediated by Fas/FasL-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathway[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 8837. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-27106-9 |

| [21] | SU L J, ZHANG J H, GOMEZ H, et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2019, 2019: 5080843. |

| [22] | KUWANA T, MACKEY M R, PERKINS G, et al. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane[J]. Cell, 2002, 111(3): 331–342. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01036-X |

| [23] | MARZO I, BRENNER C, ZAMZAMI N, et al. Bax and adenine nucleotide translocator cooperate in the mitochondrial control of apoptosis[J]. Science, 1998, 281(5385): 2027–2031. DOI: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2027 |

| [24] | YUAN Y, JIANG C Y, HU F F, et al. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cadmium-induced primary rat cerebral cortical neurons apoptosis via a mitochondrial apoptotic pathway[J]. J Trace Elem Med Biol, 2015, 29: 275–283. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.06.006 |

| [25] | SAELENS X, FESTJENS N, WALLE L V, et al. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death[J]. Oncogene, 2004, 23(16): 2861–2874. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207523 |

| [26] | NAKABAYASHI J, SASAKI A. A mathematical model for apoptosome assembly: the optimal cytochrome c/Apaf-1 ratio[J]. J Theor Biol, 2006, 242(2): 280–287. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.02.022 |

| [27] | CHAITANYA G V, ALEXANDER J S, BABU P P. PARP-1 cleavage fragments: signatures of cell-death proteases in neurodegeneration[J]. Cell Commun Signal, 2010, 8(1): 31. DOI: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-31 |

| [28] | SAIRANEN T, SZEPESI R, KARJALAINEN-LINDSBERG M L, et al. Neuronal caspase-3 and PARP-1 correlate differentially with apoptosis and necrosis in ischemic human stroke[J]. Acta Neuropathol, 2009, 118(4): 541–552. DOI: 10.1007/s00401-009-0559-3 |

| [29] |

江辰阳. 镉致大鼠神经细胞凋亡的线粒体途径及NAC的保护作用[D]. 扬州: 扬州大学, 2014.

JIANG C Y. Cadmium induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway and the protection of NAC in rat's neuronal cells[D]. Yangzhou: Yangzhou University, 2014. (in Chinses) |

| [30] | YU W R, LIU T Y, FEHLINGS T K, et al. Involvement of mitochondrial signaling pathways in the mechanism of Fas-mediated apoptosis after spinal cord injury[J]. Eur J Neurosci, 2009, 29(1): 114–131. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06555.x |

| [31] | SUSIN S A, LORENZO H K, ZAMZAMI N, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor[J]. Nature, 1999, 397(6718): 441–446. DOI: 10.1038/17135 |

| [32] | VAN LOO G, SCHOTTE P, VAN GURP M, et al. Endonuclease G: a mitochondrial protein released in apoptosis and involved in caspase-independent DNA degradation[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2001, 8(12): 1136–1142. DOI: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400944 |

| [33] | BAJT M L, COVER C, LEMASTERS J J, et al. Nuclear translocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor during acetaminophen-induced liver cell injury[J]. Toxicol Sci, 2006, 94(1): 217–225. DOI: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl077 |

| [34] | LEE S Y, OH J Y, LEE M J, et al. Anti-apoptotic mechanism and reduced expression of phospholipase D in spontaneous and Fas-stimulated apoptosis of human neutrophils[J]. Eur J Immunol, 2004, 34(10): 2760–2770. DOI: 10.1002/eji.200425117 |

| [35] | SUSIN S A, ZAMZAMI N, CASTEDO M, et al. The central executioner of apoptosis: multiple connections between protease activation and mitochondria in Fas/APO-1/CD95- and ceramide-induced apoptosis[J]. J Exp Med, 1997, 186(1): 25–37. DOI: 10.1084/jem.186.1.25 |