脓毒症是一种严重威胁人类健康的疾病。尽管近年来脓毒症病死率有所下降,但仍高达17~33.2%,且发病率逐年上升[1-3]。而脓毒症的早期危险分层被认为是指导治疗、降低病死率及提高有限医疗资源利用效率的关键措施。乳酸是对脓毒症进行危险分层和判断预后的主要标志物,不仅被纳入Sepsis-3版脓毒症休克的诊断标准,而且被广泛应用于指导脓毒症及脓毒症休克液体复苏治疗[4, 5]。研究发现,对整体而言,高乳酸血症是危重症患者预后的危险因素,但不同原因的乳酸增高患者预后显著不同[9-12]。然而,早期鉴别上述原因难以实现。那么,如何合理分层以提高乳酸对脓毒症早期危险分层的准确性,成为亟待解决的临床问题。而早期适当的抗菌治疗是治疗脓毒症最有效的措施之一[13]。那么,按感染因素分层能否提高早期乳酸对脓毒症短期预后评估的准确性呢?PCT被认为是早期鉴别全身性感染及脓毒症的最佳标志物,不仅有区分全身性感染和非感染性全身炎症的潜力,而且能区分病毒和细菌感染[14, 15]。研究表明,联合PCT和早期乳酸有助于脓毒症的诊断和危险分层[16, 17]。

既往研究已在整体水平证实,乳酸是脓毒症28天死亡的独立危险因素[18-21]。然而,在不同PCT水平下,早期高乳酸血症与脓毒症预后的关系仍不明确。本研究拟按PCT分层后,分析并比较各层间早期高乳酸血症与脓毒症28天死亡的关系。旨在明确按PCT分层能否提高早期乳酸对脓毒症短期预后评估的准确性。

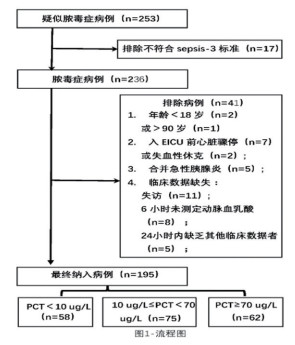

资料与方法 (一) 研究对象本研究为回顾性队列研究。纳入标准:①于2014年9月1日至2017年6月30日期间入住EICU;②符合sepsis-3脓毒症诊断标准。排除标准:①年龄<18岁,或>90岁;②入EICU前心脏骤停或失血性休克;③合并急性重症胰腺炎;④临床数据缺失者:包括结局指标失访者,或入EICU后6小时未测定动脉血乳酸者,或24小时内缺乏其他临床数据者。

(二) 数据收集、录入数据收集:①患者入EICU后一般情况、实验室检查、早期治疗等数据:早期乳酸为入EICU后6小时内首次动脉血乳酸值,其他数据取入EICU后24小时内首次检测值,按标本采集时间计算;早期治疗时间定义为入科后6小时。以上数据均从南华大学附属第一医院电子病历系统提取,并由4名医师统一培训后收集。②研究结局指标:患者入住EICU 24小时预后数据、出院后28天预后数据。由2名护士根据电子病历记录收集或电话随访。以上所有数据由双人采用EpiData数据输入软件录入并自动校对。

(三) 观察指标早期乳酸采用罗氏cobas c502全自动化分析仪检测,检测方法为比色法。降钙素原采用罗氏cobas e601全自动化分析仪检测,检测方法为电化学发光法。脓毒症患者出院后28天预后数据采用电话随访收集。

(四) 、统计分析本研究采用EmpowerStats(http://www.empowerstats.com/)统计软件分析。呈正态分布的连续型数据采用均数±标准差(x±s)描述。连续型变量满足正态分布且方差齐的两组间比较采用t检验,多组间比较采用方差分析;不同时满足态分布和方差齐时采用Mann-Whitney U秩和检验,分类变量的多组间比较采用Pearson卡方检验或Fisher确切概率法。按PCT分层,采用二元logistic回归分析早期乳酸与脓毒症患者出院28天死亡的关系。(P<0.05)有统计学意义。

结果 (一) 研究对象的一般资料本研究共收集疑似脓毒症病例253例。最终纳入脓毒症病例195例,其中男性112例(57.44%),年龄18-88岁,平均年龄为64.51±13.48岁。出院28天死亡71例(36.41%),其中24小时内死亡18例(25.35%)。脓毒症患者收集情况及分组见图 1。

|

图 1 脓毒症患者收集情况及分组 |

按早期乳酸水平分组,研究人群的一般情况、器官功能指标、早期治疗及预后情况见表 1、表 2;脓毒症28天死亡潜在危险因素的单因素分析见表 3;结合研究结果及文献,筛选出年龄、GCS评分、平均动脉压、氧合指数、总胆红素、血白蛋白、血肌酐、尿素氮、血小板计数、感染灶、有创通气、缩血管药物、6小时液体复苏量等为潜在混杂因素,PCT为交互作用因子。不同PCT梯度之间早期乳酸(LAC)和病死率的比较,见表 4;按PCT分层并调整后,各亚组间早期乳酸与脓毒症28天死亡的关系显著不同,见表 5。

| 表 1 不同LAC组间一般情况及预后的比较[n(%)] |

| 表 2 不同LAC组间器官功能指标及早期治疗的比较(x±s) |

| 表 3 脓毒症28天死亡危险因素的单因素分析 |

| 表 4 不同PCT分组间LAC和28天病死率的比较 |

| 表 5 PCT分层后早期LAC与脓毒症患者28天死亡风险分析 |

本研究195例脓毒症患者,根据早期乳酸(LAC)分组,其中LAC≥4 mmol/L组65例(33.33%),死亡37例(56.92%),其中入住EICU 24小时内死亡14例(37.84%);LAC<4 mmol/L组死亡34例(26.15%),其中24小时内死亡4例(11.77%)。单因素回归分析表明早期高乳酸血症是脓毒症28天死亡的危险因素(OR, 1.28; 95%CI, 1.14-1.43)。采用广义线性模型调整潜在混杂因素后显示,早期高乳酸血症是脓毒症28天死亡的独立危险因素(OR, 1.29;95%CI, 1.12-1.48),且调整前后的死亡风险比(OR)值相近。

(三) PCT与LAC和脓毒症28天死亡的关系与LAC<4 mmol/L组(130例)相比,LAC≥4 mmol/L组(65例)PCT水平较高,差异有统计学意义(54.78±41.07 VS 42.10±38.13,P=0.034),见表 2;按PCT水平分成低、中、高3组(分别为PCT<10 μg/L、10 μg/L≤PCT<70 μg/L、PCT≥70 μg/L),分析显示:低、中、高3组间相比,LAC的均数逐渐递增,但任意2组相比差异无统计学意义。

低、中、高PCT组的28天病死率分别为:43.1%、32.0%、35.48%,任意2组相比差异无统计学意义,见表 3。无论是单因素分析(OR, 1.00; 95%CI, 0.99-1.00),还是采用二元logistic回归分析调整潜在混杂因素后(OR, 1.00;95%CI, 0.99-1.01),PCT水平与28天死亡均无显著相关。见附表 4。

(四) 根据PCT分层,各亚组LAC与脓毒症28天死亡的关系对整体而言,LAC是脓毒症28天死亡的独立危险因素。按PCT分层,调整潜在混杂因素后显示,各亚组间LAC与脓毒症28天死亡的关系不同。当PCT<10 μg/L时,未证实早期乳酸与脓毒症28天死亡有关(OR, 0.87; 95%CI, 0.54-1.40);当10 μg/L≤PCT<70 μg/L,早期高乳酸血症是脓毒症28天死亡的独立危险因素(OR, 1.59; 95%CI, 1.06-2.37);而当PCT≥70 μg/L时,伴高乳酸血症的脓毒症患者28天死亡风险更高(OR, 2.02; 95%CI, 1.25-3.28),见表 5。

讨论脓毒症是一种严重威胁人类健康的疾病,近年来研究显示其病死率为17%-33.2%不等[1-3]。本研究中符合Sepsis-3的脓毒症28天病死率略高于既往研究,达到36.41%(n=71例),其中25.35%(n=18例)为入住EICU 24小时内死亡。其原因可能与本研究的对象均为EICU重症脓毒症患者,且纳入24小时内死亡病例有关。

脓毒症的早期危险分层被认为是指导治疗、降低病死率的关键措施。早期乳酸是临床上广泛用于脓毒症危险分层和判断预后的标志物[5]。既往的研究表明,LAC≥4 mmol/L的脓毒症患者预后不良,且独立于器官功能障碍和休克[18, 22]。本研究显示早期乳酸每增加1mmol/L,患者发生28天死亡的风险比(OR)为1.29,且独立于患者年龄、各器官功能不全、感染灶、有创通气、缩血管药物、6小时液体复苏量等因素。

既往研究已在整体水平证实,高乳酸血症是脓毒症28天死亡独立危险因素[18-21]。本研究结果也证实该结论成立。然而,高乳酸血症对于脓毒症缺乏特异性。研究表明,除了脓毒症外,高乳酸血症还可见于心源性休克、失血性休克、心脏骤停、外伤、癫痫发作、烧伤、糖尿病酮症酸中毒、肝功能不全、药物等情况[6-8]。而不同原因导致的高乳酸血症,其预后差异显著[8]。此外,研究表明,脓毒症相关高乳酸血症的机制具有多样性,如组织存在“氧债”或“低灌注”导致无氧酵解增加而导致乳酸生成增加、乳酸清除不足、肾上腺素增加骨骼肌有氧糖酵解的结果等[23]。对于脓毒症个体而言,高乳酸血症往往是多种病因和机制共同参与的结果。鉴于高乳酸血症病因的多样性和非特异性,合理分层可提高乳酸对脓毒症早期危险分层的准确性。

不同PCT水平可能反映不同的病因或病情,从而影响早期乳酸对脓毒症预后的评估。研究表明,高PCT反映机体全身性感染或脓毒症,PCT正常或轻度增高提示非感染性疾病[14]。而且,不同PCT水平可反映病原体种类、感染严重程度等方面的差异。研究显示,在细菌、疟原虫、部分真菌感染机体后,PCT迅速升高,而单纯病毒感染则无明显升高[24]。此外,对于严重全身性细菌性感染,尤其是革兰阴性杆菌导致的脓毒症时,其血浓度增加达100-10000倍以上[25]。本研究在整体水平验证高乳酸血症是脓毒症28天死亡的独立危险因素基础上,进一步按PCT分层发现,10 μg/L≤PCT < 70 μg/L和PCT≥70 μg/L的高乳酸血症才是脓毒症28天死亡的危险因素。本研究得出结论:降钙素原分层能提高早期乳酸对患者短期预后评估的准确性,进而可指导治疗及判断预后。

| [1] |

Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, et al. Assessment of Global Incidence and Mortality of Hospital-treated Sepsis. Current Estimates and Limitations[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016, 193(3): 259-272. DOI:10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC |

| [2] |

Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, et al. Incidence and Trends of Sepsis in US Hospitals Using Clinical vs Claims Data, 2009-2014[J]. Jama, 2017, 318(13): 1241-1249. DOI:10.1001/jama.2017.13836 |

| [3] |

Stevenson EK, Rubenstein AR, Radin GT, et al. Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis:a comparative meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2014, 42(3): 625-631. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000026 |

| [4] |

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [5] |

Fan SL, Miller NS, Lee J, et al. Diagnosing sepsis-The role of laboratory medicine[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2016, 460: 203-210. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2016.07.002 |

| [6] |

Gomez H, Kellum JA. Lactate in sepsis[J]. Jama, 2015, 313(2): 194-195. DOI:10.1001/jama.2014.13811 |

| [7] |

Adeva-Andany M, Lopez-Ojen M, Funcasta-Calderon R, et al. Comprehensive review on lactate metabolism in human health[J]. Mitochondrion, 2014, 17: 76-100. DOI:10.1016/j.mito.2014.05.007 |

| [8] |

Andersen LW, Mackenhauer J, Roberts JC, et al. Etiology and therapeutic approach to elevated lactate levels[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2013, 88(10): 1127-1140. DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.06.012 |

| [9] |

Cox K, Cocchi MN, Salciccioli JD, et al. Prevalence and significance of lactic acidosis in diabetic ketoacidosis[J]. J Crit Care, 2012, 27(2): 132-137. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.07.071 |

| [10] |

Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection[J]. Annals of emergency medicine, 2005, 45(5): 524-528. DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.006 |

| [11] |

Callaway DW, Shapiro NI. Serum lactate and base deficit as predictors of mortality in normotensive elderly blunt trauma patients[J]. The Journal of trauma, 2009, 66(4): 1040-1044. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181895e9e |

| [12] |

Cocchi MN, Miller J, Hunziker S, et al. The association of lactate and vasopressor need for mortality prediction in survivors of cardiac arrest[J]. Minerva anestesiologica, 2011, 77(11): 1063-1071. |

| [13] |

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(6): 1589-1596. DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9 |

| [14] |

Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2001, 164(3): 396-402. DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2009052 |

| [15] |

Ahn S, Kim WY, Kim SH, et al. Role of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in differentiation of mixed bacterial infection from 2009 H1N1 viral pneumonia[J]. Influenza and other respiratory viruses, 2011, 5(6): 398-403. DOI:10.1111/irv.2011.5.issue-6 |

| [16] |

Freund Y, Delerme S, Goulet H, et al. Serum lactate and procalcitonin measurements in emergency room for the diagnosis and risk-stratification of patients with suspected infection[J]. Biomarkers, 2012, 17(7): 590-596. DOI:10.3109/1354750X.2012.704645 |

| [17] |

赵俊泉. 降钙素原与乳酸水平对脓毒症风险分层及预后判断临床价值探讨[J]. 中国医学创新, 2012(11): 5-7. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2012.11.003 |

| [18] |

Mikkelsen ME, Miltiades AN, Gaieski DF, et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2009, 37(5): 1670-1677. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcf68 |

| [19] |

Nichol AD, Egi M, Pettila V, et al. Relative hyperlactatemia and hospital mortality in critically ill patients:a retrospective multi-centre study[J]. Crit Care, 2010, 14(1): 25. DOI:10.1186/cc8888 |

| [20] |

Houwink AP, Rijkenberg S, Bosman RJ, et al. The association between lactate, mean arterial pressure, central venous oxygen saturation and peripheral temperature and mortality in severe sepsis:a retrospective cohort analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2016, 20(1): 1-8. |

| [21] |

Howell MD, Donnino M, Clardy P, et al. Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2007, 33(11): 1892-1899. DOI:10.1007/s00134-007-0680-5 |

| [22] |

Wittayachamnankul B, Chentanakij B, Sruamsiri K, et al. The role of central venous oxygen saturation, blood lactate, and central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure difference as a goal and prognosis of sepsis treatment[J]. J Crit Care, 2016, 36: 223-229. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.08.002 |

| [23] |

Lorente L, Martin MM, Lopez-Gallardo E, et al. Higher platelet cytochrome oxidase specific activity in surviving than in non-surviving septic patients[J]. Crit Care, 2014, 18(3): 136. DOI:10.1186/cc13956 |

| [24] |

Lee H. Procalcitonin as a biomarker of infectious diseases[J]. The Korean journal of internal medicine, 2013, 28(3): 285-291. DOI:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.3.285 |

| [25] |

Vijayan AL, Vanimaya, Ravindran S, et al. Procalcitonin:a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis and antibiotic therapy[J]. J Intensive Care, 2017, 5(1): 51. DOI:10.1186/s40560-017-0246-8 |

2018, Vol. 2

2018, Vol. 2