Fe是植物生长发育所必需的微量元素。Fe在植物体内可以发生Fe3+和Fe2+的可逆转变并参与形成各种具有生理活性的铁蛋白,如细胞色素和铁氧还蛋白,其中铁氧还蛋白在植物光合电子传递、硫酸盐还原等氧化还原型生理代谢方面具有重要作用[1]。

Fe在地壳中的含量很高,但在有氧环境下,易与羟基结合形成不溶态而不能被植物直接吸收利用[2],且Fe在植物体中流动性小,Fe缺乏时植株老叶保持绿色,新叶叶脉间失绿,严重时可导致叶片白化。在长期的进化过程中,高等植物形成了不同的铁吸收机理:即机理Ⅰ和机理Ⅱ,相应的植物称为机理Ⅰ植物和机理Ⅱ植物。机理Ⅰ植物主要包括双子叶植物和非禾本科单子叶植物[3],机理Ⅰ植物吸收铁分为3个步骤,首先H+-ATPase酸化土壤中的三价铁离子,随后铁还原酶基因(Fe3+ chelate reductase,FRO)将土壤中的Fe3+还原成Fe2+,再由Fe2+转运蛋白(Iron-regulated transporter,IRT1/IRT2)将Fe2+转运至植物体内以供植物各部分生长发育[4]; 机理Ⅱ植物主要包括禾本科植物[3],其通过向胞外分泌植物铁载体(Phytoziderophore,PS)与土壤中的Fe3+螯合形成Fe3+-PS复合物,再由专一转运蛋白如黄色条纹蛋白(Yellow stripe-like,YSL)将Fe3+-PS复合物转运至植物根部细胞内。

基于Fe对植物生长发育的重要性及其被吸收形式与存在形式之间的复杂性,研究植物铁吸收机制以及相关基因的功能具有非常重要的意义,其中机理Ⅰ相关基因FRO已在多种植物中被发现与研究(表 1)。本文将对拟南芥、番茄、大豆、水稻、花生及蒺藜苜蓿等植物的FRO的亚细胞定位、还原对象、诱导条件或影响因素等方面的研究结果进行总结及探讨。

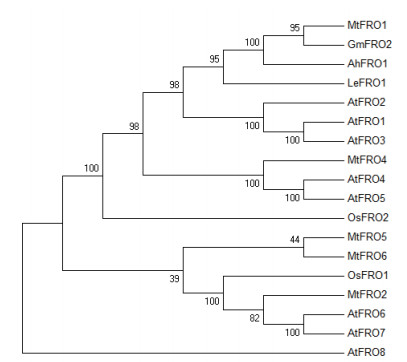

Robinson等[5]在缺铁拟南芥的根中分离出第一个高等植物FRO,并将其命名为AtFRO2。该基因编码的蛋白由725个氨基酸组成,预测等电点(pI)为9.37,相对分子质量(Mr)为81.50,属于细胞色素b大家族,拥有提供电子的膜内血红素结合位点和转运电子的胞质内核苷酸辅酶因子结合位点。因此,AtFRO2可参与胞内的电子传递,从而发挥还原三价铁的功能。其预测拓扑模型具有8个跨膜螺旋的膜蛋白、1个膜内螺旋蛋白、1个膜外螺旋蛋白和一个很大的水溶性结构域(图 1),该水溶性结构域包含NADPH、FAD和氧化还原酶结合位点(图 2),位于细胞内; N末端位于胞内,C末端位于膜外; 两对组氨酸残基位于Ⅴ、Ⅶ跨膜螺旋上并组成血红素基团结合位点(图 1); Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅸ和Ⅹ跨膜螺旋在整个家族中不保守[6],这造成FRO基因家族成员之间亚细胞定位、功能等方面差异较大。另外,利用各种植物FRO家族基因的氨基酸序列进行系统进化分析,直观地展示了FRO基因之间的亲缘关系(图 3)。

|

| 图 1 FRO的预测拓扑结构 |

|

| 用Clustal X 2.0版进行氨基酸序列比对,BOXSHADE进行着色,跨膜区用Ⅰ-Ⅹ标出 图 2 不同物种FRO蛋白的氨基酸序列比对分析 |

|

| 拟南芥Arabidopsis thaliana,AtFRO1: AEE27309.1; AtFRO2: AEE27308.1; AtFRO3: AEE30323.1; AtFRO4: AED93241.1; AtFRO5: AED93243.1; AtFRO6: AED95851.1; AtFRO7: AED95852.1; AtFRO8: AED95905.1。番茄Lycopersicum esculentum,LeFRO1: AAP46144.1。大豆Glycine max,GmFRO2: XP_003528841.1。水稻Oryza sativa,OsFRO1: BAD18962.1; OsFRO2: BAD18963.1。花生Arachis hypogaea,AhFRO1: XP_025631421.1,AhFRO2: XP_025631421.1。蒺藜苜蓿Medicago truncatula,MtFRO1: AAR15416.1; MtFRO2: XP_003594430.1; MtFRO4: XP_003592210.2; MtFRO5: ABN06137.1; MtFRO6: BAD18962.1 图 3 不同物种FRO成员的系统进化树分析 |

拟南芥是最为典型的模式植物之一,AtFRO2的发现掀开了发掘FRO基因家族的序幕。迄今为止,在拟南芥中发现的FRO基因家族共有8个成员AtFRO1-AtFRO8,按其表达部位大致可分为3类:第一类在根中表达; 第二类在幼苗中表达; 第三类在繁殖器官中表达。其中,AtFRO1的表达量极低,所以针对AtFRO1的研究很少。

在AtFRO2的基础上,Connolly等[7]用AtFRO2的反义探针作组织原位杂交发现,AtFRO2在根部表皮细胞中表达,同时将该基因的启动子与GUS融合,经染色发现,该基因也在花中表达。Vasconcelos等[8]将AtFRO2转入大豆,并在充足铁供应条件下培养,通过对根、荚皮、叶、种子中Fe、Mn、K等10种元素含量的测定发现,在种子中除了Fe的浓度有升高,Zn、Cu、Ni的浓度也有不同程度的升高,说明AtFRO2的表达不仅可以提高Fe的转运效率,也可间接促进其他离子的转运; Einset等[9]创制AtFRO2突变体frd1-1并用甜菜碱(Glycine betaine,GB)提前处理,而后在4℃低温条件下培养,发现拟南芥耐冷性显著降低,说明AtFRO2有助于GB在低温胁迫时更好地发挥对植物的保护作用。AtFRO2的表达受多水平的调控或影响,AtFRO2在缺铁条件下植株各部位mRNA表达量和相应铁还原酶活力的对比揭示了缺铁条件对该基因在转录后水平上的调控[7]; bHLH(basic helix loop helix)型转录因子FIT1(Fe-deficiency induced transcription factor,AtbHLH29)在转录水平上调控AtFRO2[10-11],该转录因子可调控多种缺铁诱导基因如IRT1、ZIP2(ZRT/IRT-like protein 2)等[12-14]。近年来,越来越多的研究表明NO、乙烯、GA、低氧碳酸氢盐、谷胱甘肽等无机或有机物也能对AtFRO2的表达产生直接或间接影响[15-19],针对AtFRO2的表达调控网络还在深入研究及完善。利用转基因技术将AtFRO2导入其他植物体,能够明显减轻植物缺铁黄化症状,而AtFRO2等位基因的变异也能引起AtFRO2表达和铁还原酶活力的改变,在分子育种领域可利用该天然变异基因改善作物在缺铁胁迫下的农艺性状[20]。这启示笔者在分子育种中插入外源基因时可寻找该外源基因的天然变异或适当对外源基因进行修饰以更好发挥该基因的功能。

AtFRO4与AtFRO5连锁,两者还原对象为Cu,在根中的转录水平很高并受转录因子SPL7(SQUAMOSA promoter binding protein-like7)调控[21]。SPL7是拟南芥中铜平衡的中心调节因子,可激活与铜稳态有关的多个基因的转录,包括miR398、铜转运蛋白和CCH(Copper chaperone)[22-23]。spl7-2的生长缺陷可在充足铁供应条件下被部分弥补,表明spl7-2突变的症状并不完全是由Cu稳态被破坏引起的,可能还包括植株严重缺Cu对Fe吸收与运输的影响[21]。所以,虽然AtFRO4和AtFRO5的还原对象为Cu,但也在一定程度上通过其转录因子SPL7活性的变化间接影响植物对Fe的吸收、运输及利用。

植物从根部吸收铁后需要在木质部中与柠檬酸等螯合成复合物进行长距离运输[24-25],到达地上部的铁复合物需再次被还原才能被利用。所以,位于地上部的FRO基因家族成员AtFRO6和AtFRO7也起着不可或缺的作用[26-27]。Wu等[10]在幼苗地上部检测到AtFRO6和AtFRO7的转录,且无论供铁条件如何,它们的转录水平都很高,说明两者的表达均不受Fe调控,属组成型表达。两者在表达部位及亚细胞定位上存在很大程度的互补: AtFRO6主要在叶片和茎中表达[28],AtFRO7在花和角果等幼嫩组织中表达量高,两者的亚细胞定位分别为质膜和叶绿体[29-30]。这种定位上的互补暗示它们在功能上的不同,但还需要大量的科学试验证实,如在烟草中过表达AtFRO6增强叶片铁还原酶活性和对缺铁黄化的耐受性,已初步证实AtFRO6编码的FRO具有在叶片中还原Fe3+的功能[31]。AtFRO6的启动子中含有多个LRE(Light-responsive element)决定了AtFRO6的表达依赖光照。另外,体外诱导AtFRO6-promoter-GUS植株根部愈伤组织形成和分化的实验证明,AtFRO6在分化的细胞或器官中表达量升高,AtFRO7也具有该特点[28]。综合以上对AtFRO6和AtFRO7特性的研究,推测AtFRO6在光照条件下于叶片细胞质膜上还原铁,并通过影响光合复合物的形成间接参与光合反应进程; AtFRO7在叶绿体中直接参与光合反应; 两者均在分化器官中表达,协同作用共同促进地上部Fe的二次还原。

AtFRO3-promoter-GUS染色结果证明AtFRO3在幼苗各部位均有表达,维管系统中表达量最高,AtFRO8的表达仅限于处在衰老过程中的嫩枝,AtFRO3和AtFRO8的亚细胞定位均为线粒体,表明两种线粒体FRO家族基因成员可能在不同发育阶段参与植株体内Fe3+-螯合物的还原[26, 32-33]。bHLH型转录因子PYE(POPEYE)可直接与AtFRO3启动子结合,转录分析表明,缺铁野生型植株中的AtFRO3表达上调,而在缺铁突变体pye-1中,AtFRO3的表达水平更高。因此,在缺铁条件下,PYE可能在一定程度上降低了AtFRO3被诱导的程度[34]。所以在今后研究AtFRO3特性及功能时应充分利用缺铁条件及突变体pye-1来提高AtFRO3的表达量以达到研究目的。

2.2 番茄FRO基因番茄是研究机理Ⅰ植物Fe吸收分子机制的重要模式植物,在缺铁胁迫下表现出典型的机理Ⅰ植物的形态和生理反应。番茄LeFRO1与拟南芥AtFRO2、豌豆PsFRO1具有较高相似度,分别为78%和81%。将该基因转入酵母进行功能分析,发现LeFRO1编码铁还原酶,且该蛋白定位在细胞膜。LeFRO1在番茄根、叶、花、果实、子叶中均有表达,且在叶中的表达水平稳定,而在根中受缺铁诱导以及FER与CHLN的调控,其中FER是一种可调控番茄根部缺铁反应的bHLH蛋白[35],该蛋白可与番茄SlbHLH068蛋白形成二聚体,并与LeFRO1启动子结合上调LeFRO1的表达[36]; CHLN编码尼克酰胺合成酶(Nicotianamine synthase),尼克酰胺(Nicotianamine)可作为螯合剂促进Fe2+在韧皮部及细胞间的运输,CHLN的缺失会引起叶脉间失绿,向根部传达缺铁信号,导致LeFRO1大量表达,即CHLN下调LeFRO1的表达[37]。合理利用以上两种蛋白对LeFRO1表达相反的调控作用可有效维持番茄植株内的Fe代谢平衡。另外,近期研究发现,LeFRO1的转录还受Fe螯合剂特性的影响,施入的Fe螯合剂不同,LeFRO1的转录水平也会发生改变[38],这可能与Fe螯合剂能够参与番茄根部的一系列缺Fe反应有关。除LeFRO1外,与其他元素吸收转运相关的基因也可受缺铁条件诱导[39-40],为提高番茄其他元素含量和改善番茄生长状况提供了新途径。在16个国内外主要番茄品种中,LeFRO1可根据其编码的氨基酸种类不同分为3种LeFRO1MM、LeFRO1Ailsa和LeFRO1Mnita,三者在酵母中的转录丰度相似,但铁还原酶活力却呈现较大差异(LeFRO1Ailsa > LeFRO1MM > LeFRO1Mnita),而三者在番茄根中的铁还原酶活力又与在酵母中不同,其中Moneymaker的铁还原酶活力在缺铁条件下显著高于其他品种,这是Moneymaker被广泛种植的原因之一[41]。由此推测酵母中转录丰度与铁还原酶活力的不对等是由于特定位点的氨基酸种类不同。酵母中与番茄根中铁还原酶活力的不对等是由于番茄根中铁还原酶活力受多种因素的影响,如品种、其他基因的调节与干扰作用、地上部新陈代谢的影响以及外部环境条件的作用等。

2.3 大豆FRO基因豆科植物在世界饮食中占有极其重要的地位,是矿质营养的主要来源。然而,其生长发育容易受土壤缺铁的影响,因缺铁导致的黄萎病严重影响豆科植物的产量[42]。所以,对豆科植物铁还原酶活力及其相关基因的研究尤为重要。与拟南芥不同,大豆GmFRO2的主要表达部位并不是根部,而是在地上部发挥着与AtFRO7相似的功能。在缺铁处理下,通过分析GmFRO2在不同品种大豆植株(抗缺绿症、感缺绿症)各部位(根、茎、子叶、单叶、三叶)的表达水平,发现其在根中的表达水平最低,其余器官的表达水平各不相同,其中抗缺绿症植株所有器官中均表现出较低的表达水平[43]。针对这一现象可作出如下解释:缺铁胁迫容易诱导铁还原酶基因的表达,缺铁条件下,抗缺绿症植株由于自身不易感特性,实际所受到的胁迫强度比感缺绿症植株小,所以抗缺绿症植株的GmFRO2的表达水平比感缺绿症植株低。大豆的品种不同可影响其根部铁还原酶活力对供铁条件的反应,如Qiu等[44]对2个吸收和利用磷效率不同的大豆品种03-3(高)和Bd-2(低)的根部铁还原酶活力进行测定,发现03-3的根系铁还原酶活性在各种处理下均高于Bd-2,且在Fe浓度为20 µmol/L的处理下,03-3植株的根系铁还原酶活性最高。尽管2个品种的铁还原酶活力大不相同,但经测定,它们的GmFRO2表达水平却非常接近,这表明该基因表达受转录后水平调控,该调控可能与植株对磷的高效利用能够提高根系铁还原酶活力有关,且该调控还需一定浓度的Fe进行诱导。大豆FRO的表达容易受品种及外界条件的影响,这增加了对大豆FRO研究的复杂性,但同时又为大豆育种及种质改良提供了多种途径。

2.4 水稻FRO基因在水稻根系特殊的生长环境中,铁大多以可溶性还原态存在,所以不需要FRO的还原作用,但水稻地上部分或旱稻中有存在FRO基因家族的可能性。2006年,Ishimaru等[45]搜索到一个与AtFRO2同源的水稻基因,并在水稻基因组中确定了2类FRO基因分别为OsFRO1和OsFRO2; Northern杂交表明,OsFRO1在缺锌、缺锰、缺铜的水稻植株叶片中表达,OsFRO2在缺铁水稻叶片中表达。OsFRO2的表达可由铁过量或持续性缺铁诱导[46-47],缺铁条件也可诱导水稻中机理Ⅰ特征基因IRT1的表达[45, 48-50],说明水稻具有2种吸收铁的机制,既是机理Ⅰ植物又是机理Ⅱ植物[51],且水稻吸收铁的机制因品种而不同。启示:水稻属禾本科植物,在传统定义中属机理Ⅱ植物,如今有此发现,而同样作为禾本科植物的小麦、玉米是否也具有此特征呢?在水稻中,缺铁会抑制根的伸长[52],事实上,可以通过将多种与吸收、转运铁相关的基因共同转入水稻植株中以显著提高铁含量、增强其对缺铁的耐受性[53],如将酵母中变异的铁还原酶基因refre1/372与OsIRT1启动子融合后转入水稻增强水稻在石灰性土壤中对缺铁的耐受性[54],该融合基因与35S-OsIRO2(OsIRO2调控机理Ⅱ植物铁吸收系统中各种基因的表达)共同转入水稻更能增强这种特性,且可大大提高植株的生物量[55]。因此,可针对OsFRO1和OsFRO2的结构与功能展开深入研究,并利用基因编辑等技术对其进行修饰以更好发挥铁还原酶功能,然后与其他基因融合转入水稻植株中,争取在更大程度上提高水稻Fe含量。

2.5 其他植物FRO基因花生是我国重要的油料作物且具有诸多营养价值与益生功效。目前,AhFRO1和AhIRT1已经在花生中被分离出来,且两者的表达均受铁缺乏和玉米花生间作的协同诱导[56-57]。花生与玉米间作是改善花生缺绿症、提高植株与荚果Fe含量的重要种植方式,与玉米间作可降低花生根际pH以及磷(P)浓度,从而提高花生根际有效Fe浓度; 与玉米间作也可诱导AhYSL1的表达,AhYSL1在花生根部表皮细胞运输Fe3+-DMA螯合物[58-59],该运输过程具有机理Ⅱ植物特征,表明花生作为机理Ⅰ植物可同时采用机理Ⅰ和机理Ⅱ 2种Fe吸收方式来抵抗缺铁带来的危害。蒺藜苜蓿作为模式豆科植物采用机理Ⅰ吸收运输Fe,继Andaluz等[60]发现MtFRO1之后,Del C Orozco-Mosqueda等[61]通过在蒺藜苜蓿全基因组范围内进行同源序列比对,发现另外5种MtFRO拷贝,并对6种MtFRO的表达进行了分析,其中MtFRO2的表达量极低; MtFRO1在铁充足条件下的表达量很低,但在铁缺乏条件下的表达量升高,尤其是地上部; MtFRO3、MtFRO4、MtFRO5和MtFRO6在铁充足条件下只在地上部表达,但在铁缺乏条件下,地上部和地下部的表达量均升高。

3 结语铁还原酶基因(FRO)编码的蛋白可以将Fe3+还原为Fe2+以供植物吸收利用,对改善作物品质、提高作物产量具有重要作用。目前,该基因在拟南芥中研究得较为透彻,但拟南芥FRO家族各成员的转录水平及转录后水平调控的分子机制还不够明朗,各成员的生理功能研究还不够全面,尤其是定位至线粒体的成员AtFRO3和AtFRO8。包括拟南芥在内,不同种植物的FRO之间以及同种植物的FRO家族成员之间均存在共性与特性。首先,除AtFRO4和AtFRO5外,各FRO的还原对象均为铁,且大部分易受缺铁诱导。其次,各FRO的主要表达部位及亚细胞定位不尽相同,但亲缘关系较近的FRO之间具有较高关联度,如AtFRO4和AtFRO5、AtFRO6和AtFRO7在系统发育树中处于同一分支,两者的主要表达部位及亚细胞定位相同或呈互补关系。最后,除拟南芥外,其他植物FRO的表达均在品种间表现出较大差异,同时各FRO具有各自独特的转录因子或影响因素,其中,bHLH家族对调节植物体内铁平衡具有至关重要的作用。拟南芥bHLH家族共有147个成员[62],FIT以及PYE均属于bHLH家族。FIT通常与其他bHLH转录因子(如bHLH38、bHLH39和bHLH101)形成异源二聚体或多聚体对其靶向基因AtFRO2发挥调控功能[63-64]。另外,PYE的表达受bHLH104与另一bHLH蛋白ILR3(IAA-LEUCINE RESISTANT3)互作的调控[65]。由此可见,bHLH家族不仅非常庞大而且成员之间的互作与调控机制错综复杂,但也为今后FRO表达调控的研究指明了方向。整体来看,FRO在水稻、小麦、玉米等主要粮食作物中的研究相对较少,主要是因为这些粮食作物属于禾本科植物,普遍被认为采用机理Ⅱ吸收铁,但越来越多的研究表明,机理Ⅱ植物中也具有机理Ⅰ特征蛋白,如玉米缺铁反应中机理Ⅰ特征转录物成分的揭露、玉米ZmZIP基因家族的发现以及过表达ZmIRT1和ZmZIP3能够促进转基因拟南芥铁和锌的积累,且FRO已在玉米中预测到[66-69]。另外,科学家已完成玉米全基因组测序,所以,在此基础上可进行玉米全基因组序列分析初步分离出玉米FRO,再分析各成员在不同铁供应条件下的表达模式及功能,为挖掘玉米铁高效基因、提高玉米等禾谷类作物铁吸收效率、增加植株及籽粒中铁含量提供新的途径。

| [1] |

Hanke GT, Kimata-Ariga Y, Taniguchi I, et al. A post genomic characterization of Arabidopsis ferredoxins[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 134(1): 255-264. DOI:10.1104/pp.103.032755 |

| [2] |

Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation. An update[J]. Febs Letters, 1992, 307(1): 108-112. DOI:10.1016/0014-5793(92)80911-Y |

| [3] |

Guerinot ML, Ying Yi. Iron: Nutritious, noxious, and not readily available[J]. Plant Physiology, 1994, 104(3): 815-820. DOI:10.1104/pp.104.3.815 |

| [4] |

Eide D, Broderius M, Fett J, et al. A novel iron-regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1996, 93(11): 5624-5628. DOI:10.1073/pnas.93.11.5624 |

| [5] |

Robinson NJ, Procter CM, Connolly EL, et al. A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils[J]. Nature, 1999, 397(6721): 694-697. DOI:10.1038/17800 |

| [6] |

Schagerlof U, Wilson G, Hebert H, et al. Transmembrane topology of FRO2, a ferric chelate reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant Mol Biol, 2006, 62(1/2): 215-221. |

| [7] |

Connolly EL, Campbell NH, Grotz N, et al. Overexpression of the FRO2 ferric chelate reductase confers tolerance to growth on low iron and uncovers posttranscriptional control[J]. Plant Physiology, 2003, 133(3): 1102-1110. DOI:10.1104/pp.103.025122 |

| [8] |

Vasconcelos MW, Clemente TE, Grusak MA. Evaluation of constitutive iron reductase(AtFRO2)expression on mineral accumulation and distribution in soybean(Glycine max L.)[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2014, 5: 112. |

| [9] |

Einset J, Winge P, Bones AM, et al. The FRO2 ferric reductase is required for glycine betaine's effect on chilling tolerance in Arabidopsis roots[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2008, 134(2): 334-341. DOI:10.1111/ppl.2008.134.issue-2 |

| [10] |

Wu H, Li LH, Du J, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of the Fe(Ⅲ)chelate reductase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2005, 46(9): 1505-1514. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pci163 |

| [11] |

Sivitz A, Grinvalds C, Barberon M, et al. Proteasome-mediated turnover of the transcriptional activator FIT is required for plant iron-deficiency responses[J]. Plant J, 2011, 66(6): 1044-1052. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2011.66.issue-6 |

| [12] |

Mai HJ, Pateyron S, Bauer P. Iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana: transcriptomic analyses reveal novel FIT-regulated genes, iron deficiency marker genes and functional gene networks[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2016, 16(1): 211. DOI:10.1186/s12870-016-0899-9 |

| [13] |

Colangelo EP, Guerinot ML. The essential basic helix-loop-helix protein FIT1 is required for the iron deficiency response[J]. The Plant Cell, 2004, 16(12): 3400-3412. DOI:10.1105/tpc.104.024315 |

| [14] |

Brumbarova T, Bauer P, Ivanov R. Molecular mechanisms governing Arabidopsis iron uptake[J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2015, 20(2): 124-133. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.11.004 |

| [15] |

Garcia MJ, Suarez V, Romera FJ, et al. A new model involving ethylene, nitric oxide and Fe to explain the regulation of Fe-acquisition genes in Strategy Ⅰ plants[J]. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2011, 49(5): 537-544. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.01.019 |

| [16] |

Lucena C, Romera FJ, Garcia MJ, et al. Ethylene participates in the regulation of Fe deficiency responses in strategy Ⅰ plants and in rice[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2015, 6: 1056. |

| [17] |

Wild M, Davière JM, Regnault T, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of gibberellin signaling fine-tunes Arabidopsis iron-deficiency responses[J]. Developmental Cell, 2016, 37(2): 190-200. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.03.022 |

| [18] |

Garcia MJ, Garcia-Mateo MJ, Lucena C, et al. Hypoxia and bicarbonate could limit the expression of iron acquisition genes in Strategy Ⅰ plants by affecting ethylene synthesis and signaling in different ways[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2014, 150(1): 95-106. |

| [19] |

Shanmugam V, Wang YW, Tsednee M, et al. Glutathione plays an essential role in nitric oxide-mediated iron-deficiency signaling and iron-deficiency tolerance in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant J, 2015, 84(3): 464-477. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2015.84.issue-3 |

| [20] |

Satbhai SB, Setzer C, Freynschlag F, et al. Natural allelic variation of FRO2 modulates Arabidopsis root growth under iron deficiency[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 15603. DOI:10.1038/ncomms15603 |

| [21] |

Bernal M, Casero D, Singh V, et al. Transcriptome sequencing identifies SPL7-regulated copper acquisition genes FRO4/FRO5 and the copper dependence of iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis[J]. The Plant Cell, 2012, 24(2): 738-761. DOI:10.1105/tpc.111.090431 |

| [22] |

Yamasaki H, Hayashi M, Fukazawa M, et al. SQUAMOSA promoter binding protein-like7 is a central regulator for copper homeostasis in Arabidopsis[J]. The Plant Cell, 2009, 21(1): 347-361. DOI:10.1105/tpc.108.060137 |

| [23] |

Gielen H, Remans T, Vangronsveld J, et al. Toxicity responses of Cu and Cd: the involvement of miRNAs and the transcription factor SPL7[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2016, 16(1): 145. DOI:10.1186/s12870-016-0830-4 |

| [24] |

Rellan-Alvarez R, Giner-Martínez-Sierra J, Orduna J, et al. Identification of a tri-iron(Ⅲ), tri-citrate complex in the xylem sap of iron-deficient tomato resupplied with iron: new insights into plant iron long-distance transport[J]. Plant Cell Physiol, 2010, 51(1): 91-102. |

| [25] |

Gayomba SR, Zhai Z, Jung HI, et al. Local and systemic signaling of iron status and its interactions with homeostasis of other essential elements[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2015, 6: 716. |

| [26] |

Mukherjee I, Campbell NH, Ash JS, et al. Expression profiling of the Arabidopsis ferric chelate reductase(FRO)gene family reveals differential regulation by iron and copper[J]. Planta, 2006, 223(6): 1178-1190. DOI:10.1007/s00425-005-0165-0 |

| [27] |

Lopez-Millan AF, Duy D, Philippar K. Chloroplast iron transport proteins - function and impact on plant physiology[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2016, 7: 178. |

| [28] |

Feng HZ, An FY, Zhang SZ, et al. Light-regulated, tissue-specific, and cell differentiation-specific expression of the Arabidopsis Fe(Ⅲ)-chelate reductase gene AtFRO6[J]. Plant Physiology, 2006, 140(4): 1345-1354. DOI:10.1104/pp.105.074138 |

| [29] |

Jeong J, Cohu C, Kerkeb L, et al. Chloroplast Fe(Ⅲ)chelate reductase activity is essential for seedling viability under iron limiting conditions[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(30): 10619-10624. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0708367105 |

| [30] |

Jain A, Wilson GT, Connolly EL. The diverse roles of FRO family metalloreductases in iron and copper homeostasis[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2014, 5: 100. |

| [31] |

Li LY, Cai QY, Yu DS, et al. Overexpression of AtFRO6 in transgenic tobacco enhances ferric chelate reductase activity in leaves and increases tolerance to iron-deficiency chlorosis[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2011, 38(6): 3605-3613. DOI:10.1007/s11033-010-0472-9 |

| [32] |

Jain A, Connolly EL. Mitochondrial iron transport and homeostasis in plants[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2013, 4: 348. |

| [33] |

Jeong J, Connolly EL. Iron uptake mechanisms in plants: Functions of the FRO family of ferric reductases[J]. Plant Science, 2009, 176(6): 709-714. DOI:10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.02.011 |

| [34] |

Long TA, Tsukagoshi H, Busch W, et al. The bHLH transcription factor POPEYE regulates response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis roots[J]. The Plant Cell, 2010, 22(7): 2219-2236. DOI:10.1105/tpc.110.074096 |

| [35] |

Ling HQ, Bauer P, Bereczky Z, et al. The tomato fer gene encoding a bHLH protein controls iron-uptake responses in roots[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2002, 99(21): 13938-13943. DOI:10.1073/pnas.212448699 |

| [36] |

Du J, Huang ZA, Wang B, et al. SlbHLH068 interacts with FER to regulate the iron-deficiency response in tomato[J]. Annals of Botany, 2015, 116(1): 23-34. |

| [37] |

Li LH, Cheng XD, Ling HQ. Isolation and characterization of Fe(Ⅲ)-chelate reductase gene LeFRO1 in tomato[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2004, 54(1): 125-136. DOI:10.1023/B:PLAN.0000028774.82782.16 |

| [38] |

Zamboni A, Zanin L, Tomasi N, et al. Early transcriptomic response to Fe supply in Fe-deficient tomato plants is strongly influenced by the nature of the chelating agent[J]. BMC Genomics, 2016, 17: 35. DOI:10.1186/s12864-015-2331-5 |

| [39] |

Zamboni A, Zanin L, Tomasi N, et al. Genome-wide microarray analysis of tomato roots showed defined responses to iron deficiency[J]. BMC Genomics, 2012, 13: 101. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-13-101 |

| [40] |

Paolacci AR, Celletti S, Catarcione G, et al. Iron deprivation results in a rapid but not sustained increase of the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism and sulfate uptake in tomato(Solanum lycopersicum L.)seedlings[J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2014, 56(1): 88-100. DOI:10.1111/jipb.v56.1 |

| [41] |

Kong DY, Chen CL, Wu HL, et al. Sequence diversity and enzyme activity of ferric-chelate reductase LeFRO1 in tomato[J]. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 2013, 40(11): 565-573. DOI:10.1016/j.jgg.2013.08.002 |

| [42] |

Prasad PVV. NUTRITION _ Iron Chlorosis[M]. Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences, 2003: 649-656.

|

| [43] |

Santos CS, Roriz M, Carvalho SM, et al. Iron partitioning at an early growth stage impacts iron deficiency responses in soybean plants(Glycine max L.)[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2015, 6: 325. |

| [44] |

Qiu W, Dai J, Wang NQ, et al. Effects of Fe-deficient conditions on Fe uptake and utilization in P-efficient soybean[J]. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2017, 112: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.12.010 |

| [45] |

Ishimaru Y, Suzuki M, Tsukamoto T, et al. Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+-phytosiderophore and as Fe2+[J]. Plant J, 2006, 45(3): 335-346. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2006.45.issue-3 |

| [46] |

Finatto T, de Oliveira AC, Chaparro C, et al. Abiotic stress and genome dynamics: specific genes and transposable elements response to iron excess in rice[J]. Rice, 2015, 8: 13. DOI:10.1186/s12284-015-0045-6 |

| [47] |

Pereira MP, Santos C, Gomes A, et al. Cultivar variability of iron uptake mechanisms in rice(Oryza sativa L.)[J]. Plant Physiol and Biochemistry, 2014, 85: 21-30. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.10.007 |

| [48] |

Li Q, Yang A, Zhang WH. Efficient acquisition of iron confers greater tolerance to saline-alkaline stress in rice(Oryza sativa L.)[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2016, 67(22): 6431-6444. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erw407 |

| [49] |

Kobayashi T, Nakanishi IR, Nishizawa NK. Iron deficiency responses in rice roots[J]. Rice, 2014, 7(1): 27. DOI:10.1186/s12284-014-0027-0 |

| [50] |

Cheng LJ, Wang F, Shou HX, et al. Mutation in nicotianamine aminotransferase stimulated the Fe(Ⅱ)acquisition system and led to iron accumulation in rice[J]. Plant Physiology, 2007, 145(4): 1647-1657. DOI:10.1104/pp.107.107912 |

| [51] |

Ricachenevsky FK, Sperotto RA. There and back again, or always there? The evolution of rice combined strategy for Fe uptake[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2014, 5: 189. |

| [52] |

Sun HW, Feng F, Liu J, et al. The interaction between auxin and nitric oxide regulates root growth in response to iron deficiency in rice[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2017, 8: 2169. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.02169 |

| [53] |

Santos RS, Araujo AT, Pegoraro C, et al. Dealing with iron metabolism in rice: from breeding for stress tolerance to biofortification[J]. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 2017, 40(1): 312-325. |

| [54] |

Ishimaru Y, Kim S, Tsukamoto T, et al. Mutational reconstructed ferric chelate reductase confers enhanced tolerance in rice to iron deficiency in calcareous soil[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2007, 104(18): 7373-7378. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0610555104 |

| [55] |

Masuda H, Shimochi E, Hamada T, et al. A new transgenic rice line exhibiting enhanced ferric iron reduction and phytosiderophore production confers tolerance to low iron availability in calcareous soil[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(3): e0173441. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0173441 |

| [56] |

Ding H, Duan LH, Wu HL, et al. Regulation of AhFRO1, an Fe(Ⅲ)-chelate reductase of peanut, during iron deficiency stress and intercropping with maize[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 2009, 136(3): 274-283. DOI:10.1111/ppl.2009.136.issue-3 |

| [57] |

Ding H, Duan LH, Li J, et al. Cloning and functional analysis of the peanut iron transporter AhIRT1 during iron deficiency stress and intercropping with maize[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology, 2010, 167(12): 996-1002. DOI:10.1016/j.jplph.2009.12.019 |

| [58] |

Xiong H, Shen H, Zhang L, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis for assessment of the ecological significance of maize and peanut intercropping[J]. Journal of Proteomics, 2013, 78: 447-460. DOI:10.1016/j.jprot.2012.10.013 |

| [59] |

Guo XT, Xiong HC, Shen HY, et al. Dynamics in the rhizosphere and iron-uptake gene expression in peanut induced by intercropping with maize: role in improving iron nutrition in peanut[J]. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2014, 76: 36-43. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.019 |

| [60] |

Andaluz S, Rodriguez-Celma J, Abadia A, et al. Time course induction of several key enzymes in Medicago truncatula roots in response to Fe deficiency[J]. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2009, 47(11/12): 1082-1088. |

| [61] |

Del C orozco-Mosqueda M, Santoyo G, Farías-Rodríguez R, et al. Identification and expression analysis of multiple FRO gene copies in Medicago truncatula[J]. Genetics and Molecular Research, 2012, 11(4): 4402-4410. DOI:10.4238/2012.October.9.7 |

| [62] |

Toledo-Ortiz G. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family[J]. The Plant Cell, 2003, 15(8): 1749-1770. DOI:10.1105/tpc.013839 |

| [63] |

Yuan Y, Wu HL, Wang N, et al. FIT interacts with AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 in regulating iron uptake gene expression for iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis[J]. Cell Research, 2008, 18(3): 385-397. DOI:10.1038/cr.2008.26 |

| [64] |

Wang N, Cui Y, Liu Y, et al. Requirement and functional redundancy of Ib subgroup bHLH proteins for iron deficiency responses and uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Molecular Plant, 2013, 6(2): 503-513. DOI:10.1093/mp/sss089 |

| [65] |

Zhang J, Liu B, Li MS, et al. The bHLH transcription factor bHLH104 interacts with IAA-LEUCINE RESISTANT3 and modulates iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 2015, 27(3): 787-805. DOI:10.1105/tpc.114.132704 |

| [66] |

Li SZ, Zhou XJ, Li HB, et al. Overexpression of ZmIRT1 and ZmZIP3 enhances iron and zinc accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0136647. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0136647 |

| [67] |

Li SZ, Zhou XJ, Huang YQ, et al. Identification and characterization of the zinc-regulated transporters, iron-regulated transporter-like protein(ZIP)gene family in maize[J]. BMC Plant Biology, 2013, 13(1): 114. DOI:10.1186/1471-2229-13-114 |

| [68] |

Zanin L, Venuti S, Zamboni A, et al. Transcriptional and physiological analyses of Fe deficiency response in maize reveal the presence of Strategy Ⅰ components and Fe/P interactions[J]. BMC Genomics, 2017, 18(1): 154. DOI:10.1186/s12864-016-3478-4 |

| [69] |

Li SZ, Zhou XJ, Chen JT, et al. Is there a strategy Ⅰ iron uptake mechanism in maize?[J]. Plant Signal Behavior, 2018, 13(4): e1161877. DOI:10.1080/15592324.2016.1161877 |