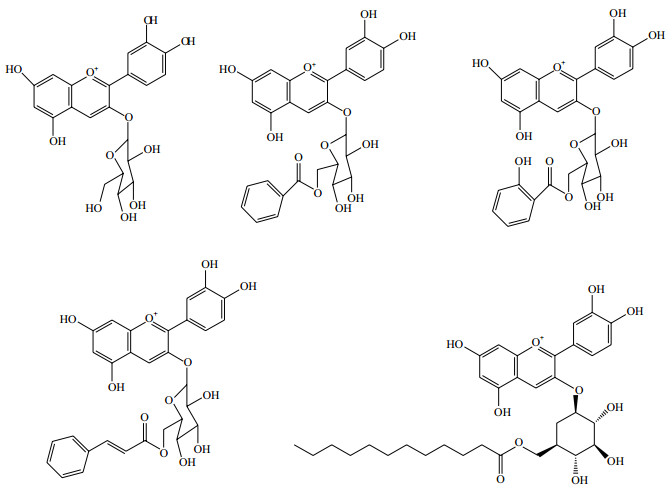

花色苷(Anthocyanin)是植物界中广泛存在的水溶性色素物质, 迄今从自然界分离和鉴定出的花色苷多达600余种, 主要由6种花青素衍生而来, 分别为矢车菊素(Cyanidin)、飞燕草素(Delphinidin)、天竺葵素(Pelargonidin)、芍药花素(Peonidin)、矮牵牛素(Petunidin)和锦葵色素(Malvidin), 这6种花青素占全部花色素种类的95%以上[1](图 1)。花色苷的结构差异主要体现在环上羟基的数目、糖基的数量和糖的结构, 其中矢车菊素-3-葡萄糖苷(Cyanidin-3-glucoside, C3G)在所有花色苷类物质中含量最多、分布最为广泛[1]。花色苷类物质除了能使植物叶片、花朵、茎和果实等呈现五彩斑斓的颜色外, 还具有显著的生物活性, 如抗炎、抗氧化、延缓衰老、改善胰岛功能、诱导肿瘤细胞凋亡及提高免疫力等[1-4]。因此花色苷在食品、化妆品、医药领域等有巨大的发展前景, 是替代合成色素的理想材料[5-6]。

|

| 图 1 天然花青素的组成、结构及分布 |

由于花色苷存在多个活性羟基和含正离子的母核, 使其化学性质极为活泼, 易致色泽或活性消失[7], 同时多羟基基团的存在使花色苷具有较强的亲水性, 而在透膜性上存在较大障碍, 导致其生物利用度不高, 在食品、药品、化妆品等行业中的应用尚不普遍, 其多种生物活性的作用不能很好发挥[8]。研究发现, 一些取代基如脂肪酸和芳香酸会与花色苷糖基上的羟基进行缩合, 从而形成不同种类的酰基化花色苷, 构效关系研究表明, 酰基化花色苷具有比花色苷更好的稳定性和生物利用度[9]。如Zhao等[10]发现, 经月桂酰化的C3G在高温和光照下的稳定性显著高于未酰化的C3G。

酰基化花色苷是在植物体内生物合成或由富含花色苷果蔬在发酵过程中由微生物转化形成的一系列花色苷衍生物。研究者陆续从一些蔬菜(如紫甘蓝、红萝卜、紫薯和紫玉米等)和植物的花中分离鉴定出一些稳定性高、生物活性好的脂肪族或芳香族的酰基化花色苷。但是, 由于本身的含量低, 提取工艺复杂, 收率较低[11-12]。化学法是花色苷酰基修饰的有效方法之一, 但利用化学法对多羟基结构的花色苷进行酰基化时不可避免的需要经过加保护、去保护等步骤, 反应条件复杂, 且对催化剂要求高, 环境不友好[13]。相对于化学法, 生物法简单可控、条件温和, 具有高效、高区域选择性和环境友好等优点, 愈来愈受到人们的瞩目[14-16]。为了促进花色苷生物转化改善其结构性能和功能特性的研究, 提高花色苷高效生物转化达到提升其结构稳定性和生物活性的目的, 本文对花色苷的稳定性、生物活性性质, 以及其生物转化酰基化修饰的进展进行了综述, 并对酰基化修饰的效果及应用前景进行了分析展望, 以期为花色苷生物转化修饰研究提供参考。

1 花色苷的稳定性花色苷由花色素和糖类物质经糖苷键缩合而成, 其结构母核是2-苯基苯并吡喃阳离子, 属于黄酮类化合物。由于花色苷的花色素核以正离子形式存在, 且结构上存在多个活性羟基, 性质比较活泼, 对酸碱度、光照、温度等因素敏感, 稳定性较差。

研究发现, 光既能作为合成花色苷的重要因子, 也能加速花色苷的降解。Furtado等[17]推测, 花色苷可能先降解生成C4羟基的中间产物, 该中间产物在C2位上水解开环, 最后生成查尔酮, 查尔酮快速降解成苯甲酸及2, 4, 6-三羟基苯甲醛等产物。花色苷在光照的条件下褪色更快, 在避光的条件下褪色要慢。研究发现, 在光照条件下, 二糖苷的稳定性比单糖苷强, 而酰基化后的二糖苷更是比未经过酰化的二糖苷更稳定。

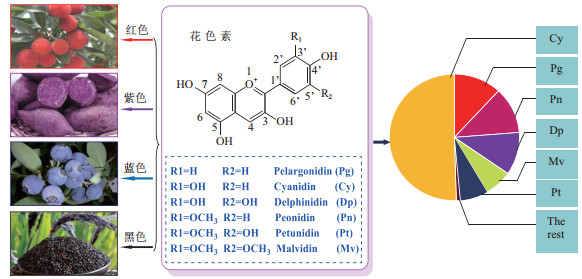

另外, 温度和时间对花色苷也有很大的影响。Maciel等[18]研究了温度对木槿花萼花青素稳定的影响, 结果发现, 温度对花色苷和总黄酮含量有显著影响, 温度高于80℃时, t1/2和颜色保持率显著降低。而当温度发生变化时, 花色苷的结构在无色的查尔酮和甲醇假碱存在形式和红色的花色烊阳离子存在形式之间发生变化, 实验表明, 在温度升高时, 平衡就会向着前者转化, 但当冷却和酸化时, 醌式碱和甲醇假碱就会转变成后者。也有发现蓝莓花色苷的稳定性易受温度和pH值的影响。无论是总花色苷还是单体花色苷, 低温和低pH的条件对花色苷稳定性的保持都是有利的。研究发现, 当溶液中pH发生变化的同时, 花色苷的结构会发生了转化[19], 当pH的范围小于2时, 花色苷以花色烊阳离子的形式存在, 呈红色; 当pH的范围为3-6时, 花色苷以甲醇假碱和查尔酮假碱的形式存在, 呈无色; 当pH的范围为中性或者为在微酸的环境下, 花色苷以中性的醌式碱的形式存在, 呈紫色或浅紫色; 当pH的范围为8-10时, 花色苷以共振稳定的醌式碱的形式存在, 呈紫色或蓝色(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 室温条件下花色苷在不同pH水溶液中的平衡与颜色变化 |

由此可见, 在花色苷的运输和加工过程中, 采取避光低温的措施, 可以减少花色苷的降解, 避免不必要的损失。同时, 将花色苷置于酸性条件下, 也可以一定程度上提高花色苷的稳定性, 增加花色苷的利用率。

2 花色苷的生物活性目前, 国内外有关花色苷生物活性的报道有很多, 花色苷的生理活性包括维持血糖、预防心血管疾病、保护心脏肝脏、保护神经及具有抗氧化活性等多个方面。

近年来, 肥胖成为全球主要的健康问题之一, 花青素可通过抑制脂肪吸收、增加能量消耗、调节脂质代谢、抑制食物摄入和调节肠道微生物群等方式达到抗肥胖的作用[20]。Song等[21]则在研究中发现, 蓝莓花色苷可以有效控制并降低血液中的血糖含量, 更可以作为一种有用的辅助剂, 抑制糖尿病引起的视网膜异常并防止糖尿病视网膜病变的发生。同时, 花色苷还能有效的缓解由糖尿病所引发的慢性炎症、心脏肥大及细胞细胞凋亡等多种并发症, 具有一定的抗炎、抗氧化及心脏保护性能[22]。另外, 花色苷对心血管和神经都有保护作用[23], Peixoto等[24]认为花色苷的ACAI提取物发挥了神经保护作用, 可以在一定程度上预防或控制神经衰退性疾病。

研究发现, 花色苷众多生物活性的根本机制是花色苷的抗氧化活性。Wang等[25]通过调查蔓越莓花色苷提取物对果蝇寿命的影响, 发现蔓越莓花色苷提取物可以延长果蝇寿命。Wang等[26]发现紫甘薯花青素能有效去除羟基自由基, 减少脂质过氧化的发生, 具有保护肝脏免受CCl4损伤的功能。还有许多人对不同物质的花色苷的抗氧化活性进行了研究[27-29], 结果表明, 大多数花色苷都有较强的抗氧化活性, 可用于开发具有抗氧化活性的功能性食品。

3 花色苷的生物转化修饰作为人类饮食中天然存在的组分, 花色苷的价值极高, 然而, 由于花色苷的结构原因, 花色苷结构不稳定, 也不容易被人体吸收, 因此可以通过生物转化的方式, 提高花色苷在体外的稳定性, 也可以在体内将花色苷转化为小分子物质, 以便于提高花色苷的利用率。

3.1 植物细胞转化在生物转化的研究中, 有人利用植物细胞进行生物转化, 这种转化方式具有选择性强、反应条件温和、催化效率高、环境污染小及副产物少等多种优点。研究发现, 通过植物组织培养的方法合成花青素, 既能提高花青素的产量, 同时也可以增加花青素的稳定性。Konczak-Islam等[30]在改进后的MS培养基上培养紫甘薯植物细胞, 发现未经过酰化的花青素YGM-oa和YGM-ob的相对含量分别减少了34.8%和15.9%, 而经过酰化的花青素的相对含量却有所提高; Donaldk等[14]利用添加了苯乙烯酸和其他芳香酸的胡萝卜培养液, 得到了14种新型单酰化花青素, 经实验测定, 这些花青素在接近中性的条件下, 依旧可以较好地保持颜色。同时, Donaldk也发现经过苯乙烯酸酰化以后的花青素的稳定性比其相应的其他芳香酸的更高。Konczak等[31]则是通过基因工程技术, 利用甜薯的植物细胞, 培养出了具有高稳定性、强生理活性、高花色苷含量的植株。

3.2 酶法转化研究表明, 通过对花色苷进行结构修饰可以提高花色苷的稳定性, 利用化学法对花色苷进行结构修饰存在诸多缺点[32], 而酶具有较高的专一性和选择性。同时, 酶的反应条件温和, 催化效率高, 且酶在非水介质中还具有许多水溶液所不具备的新特点[33]。Yan等[34]研究表明, 利用酶法修饰异槲皮苷后所形成的新复合物, 具有高抗氧化性能, 显著改善了花色苷在不同pH水平下的热稳定性和光稳定性。

另外, 用酶对花色苷进行酰化作用以达到增强花色苷稳定的方法也是研究的热点, 已用酶法合成了一系列花色苷酯衍生物[10, 16](图 3)。Yan等[35]利用甲基芳香族脂作为酰基供体, 用脂肪酶作为生物催化剂对黑米花色苷进行酶促反应发现, 芳香族羧酸酰化增强了花色素苷的热稳定性。Castro等[16]以棕榈酸为酰基供体, 用脂肪酶酶促酰化刺果桃金娘(Myrciaria caiflura)果实的花色苷粗提物, 合成了含有飞燕草素-3-葡萄糖苷和花青素-3-葡萄糖苷的棕榈酸单酯。Zhao等[10]将C3G与月桂酸利用混合酶作为催化剂在二甲基甲酰胺中进行酰基化修饰。这使酶法催化花色苷选择性酰化实现结构稳定化引起更多关注并得到更广泛的运用。

3.3 微生物细胞转化近年来越来越多的研究采用微生物全细胞作为酶催化剂应用于花色苷类物质的生物转化[36], 微生物细胞催化主要利用胞膜或胞壁连接的水解酶或胞内水解酶, 并以微生物细胞为载体, 可以省去酶分离纯化及固定化等步骤, 从而大大地降低生产成本[37], 还能显著提高产物收率和反应区域选择性[38]。

宋静[39]发现假丝酵母(Candida saitoana SX-11)可作为微生物转化蓝靛果花色苷稳定性菌株, 在辅色素的协同作用下, 可以提高蓝靛果花色苷的稳定性。目前, 国内外对于微生物细胞转化这方面的研究着重于肠道微生物对花色苷的转化降解作用。研究发现, 大多数肠道菌群均具有β-葡萄糖苷酶活性, 并且参与植物β-葡萄糖苷酶的水解, 可以将花色苷有效的转化为具有高生物利用度和药理活性的化合物[39]。Cheng等[40]在37℃的厌氧条件下, 将五种肠道益生菌和桑葚花青素一起培养, 结果显示具有高β-葡萄糖苷酶生产能力的嗜热链球菌GIM 1.321和植物乳杆菌GIM 1.35对桑葚花青素的降解能力分别为46.17%和43.62%。这说明花色苷在体内易被肠道微生物所降解, 从而被人体吸收。花色苷是由糖基链接, 因此花色苷在消化道不易被吸收, 但花色苷能在肠道内被肠道细菌糖苷酶水解为糖苷配基, 或进一步降解为酚酸[41]。当花色苷被摄入后, 经糖苷酶水解, 产生的苷元在大肠中进一步代谢为其他代谢物, 如原儿茶酸、没食子酸、丁香酸和香草酸[42-44]。然而花色苷转化为生物活性形式所涉及的肠道细菌类型的花色苷的微生物生物转化功效尚未有定论。

4 展望随着人们对生活水平及人体健康的要求越来越高, 花色苷作为一种天然且具有一定营养和药理作用的食用色素, 越来越受到人们的关注, 花色苷在食品、化妆、医药等各方面具有潜在的巨大应用价值, 由于花色苷本身性质不稳定, 使得通过生物转化对花色苷进行改性研究具有重要意义。

目前通过花色苷酰基化修饰研究, 已经获得了具有较高结构稳定性和生物利用度的花色苷衍生物, 为花色苷更广泛应用点奠定基础。但目前酶促糖苷类化合物酰化技术仍存在一些问题, 筛选合适的酶增大底物改性效率, 以寻求更加高效、环保、经济的改性方法, 是对天然花色苷类化合物进行改性并改善其生物利用度的一个研究方向, 同时在酶促酰基供体的选择、酰化位点的确定、溶剂体系的筛选与配制等还需要开展进一步的工作。此外, 在全细胞生物转化研究中, 由于微生物细胞中含有大量的混合酶, 也可对花色苷进行生物转化以提高其稳定性, 这些都会成为生物转化花色苷的研究方向, 而定向选育高转化效率的微生物菌种成为其中重要的一步, 可以进一步通过诱变育种、分子生物学和基因工程育种方法, 更有效地提高菌种选育效率, 获得更多花色苷修饰产物, 进一步推动其广泛应用。

| [1] |

He J, Giusti MM. Anthocyanins:natural colorants with health-promoting properties[J]. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol, 2010, 1(7): 163-187. |

| [2] |

Serra D, Almeida LM, Dinis TCP. Anti-inflammatory protection afforded by cyanidin-3-glucoside and resveratrol in human intestinal cells via Nrf2 and PPAR-γ:comparison with 5-aminosalicylic acid[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2016, 260: 102-109. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.11.003 |

| [3] |

Kopjar M, Orsolic M, Pilizota V. Anthocyanins, phenols, and antioxidant activity of sour cherry puree extracts and their stability during storage[J]. Int J Food Prop, 2014, 17(6): 1393-1405. DOI:10.1080/10942912.2012.714027 |

| [4] |

崔清慧.蓝莓花色苷的酰化及抑制Hep G2和Caco-2细胞增殖活性的研究[D].北京: 北京林业大学, 2016. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10022-1016139983.htm

|

| [5] |

Shelly H, Hyun C, Lei Z, et al. Antiproliferative and antioxidant properties of anthocyanin-rich extract from acai[J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 118(2): 208-214. |

| [6] |

Xu JW, Ikeda K, Yamori Y. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by cyanidin-3-glucoside, a typical anthocyanin pigment[J]. Hypertension, 2004, 44(2): 217-222. DOI:10.1161/01.HYP.0000135868.38343.c6 |

| [7] |

Rein M. Copigmentation reactions and color stability of berry anthocyanins[D]. Helsinki: University of Helsinki, 2005.

|

| [8] |

Hassimotto NMA, Genovese MI, Lajolo FM. Absorption and metabolism of cyanidin-3-glucoside and cyanidin-3-rutinoside extracted from wild mulberry(Morus nigra L.)in rats[J]. Nutrition Research, 2008, 28(3): 198-207. DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2007.12.012 |

| [9] |

Zhao CL, Yu YQ, Chen ZJ, et al. Stability-increasing effects of anthocyanin glycosyl acylation[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 214: 119-128. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.073 |

| [10] |

Zhao LY, Chen J, Wang ZQ, et al. Direct acylation of cyanidin-3-glucoside with lauric acid in blueberry and its stability analysis[J]. Int J Food Prop, 2016, 19(1): 1-12. DOI:10.1080/10942912.2015.1016577 |

| [11] |

Matera R, Gabbanini S, Berretti S, et al. Acylated anthocyanins from sprouts of Raphanus sativus cv. Sango:Isolation, structure elucidation and antioxidant activity[J]. Food Chemistry, 2015, 166: 397-406. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.056 |

| [12] |

Jordheim M, Calcott K, Gould KS, et al. High concentrations of aromatic acylated anthocyanins found in cauline hairs in Plectranthus ciliatus[J]. Phytochemistry, 2016, 128: 27-34. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.04.007 |

| [13] |

Oyama K, Kawaguchi S, Yoshida K, et al. Synthesis of pelargonidin 3-O-6''-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, an acylated anthocyanin, via the corresponding kaempferol glucoside[J]. Tetrahedron Letters, 2007, 48(34): 6005-6009. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.06.134 |

| [14] |

Dougall DK, Baker DC, Gakh EG, et al. Anthocyanins from wild carrot suspension cultures acylated with supplied carboxylic acids[J]. Carbohydrate Research, 1998, 310(3): 177-189. DOI:10.1016/S0008-6215(98)00124-4 |

| [15] |

Sari P, Setiawan A, Siswoyo TA. Stability and antioxidant activity of acylated jambolan(Syzygium cumini)anthocyanins synthesized by lipase-catalyzed transesterification[J]. International Food Research Journal, 2015, 22(2): 671-676. |

| [16] |

Castro VC, Silva PHA, Oliveira EB, et al. Extraction, identification and enzymatic synthesis of acylated derivatives of anthocyanins from jaboticaba(Myrciaria cauliflora)fruits[J]. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2014, 49(1): 196-204. |

| [17] |

Furtado P, Figueiredo P, Neves HCD, et al. Photochemical and thermal degradation of anthocyanidins[J]. J Photoch Photobiol, 1993, 75(2): 113-118. DOI:10.1016/1010-6030(93)80191-B |

| [18] |

Maciel LG, Do C, Azevedo L, et al. Hibiscus sabdariffa anthocya-nins-rich extract:Chemical stability, in vitro antioxidant and antiproliferative activities[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2018, 113: 187-197. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2018.01.053 |

| [19] |

Luna-vital D, Li Q, West L, et al. Anthocyanin condensed forms do not affect color or chemical stability of purple corn pericarp extracts stored under different pHs[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 232: 639-647. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.03.169 |

| [20] |

Xie LH, Su HM, Sun CD, et al. Recent advances in understanding the anti-obesity activity of anthocyanins and their biosynthesis in microorganisms[J]. Trends Food Sci Technol, 2018, 72: 13-24. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.12.002 |

| [21] |

Song Y, Huang LL, Yu JF. Effects of blueberry anthocyanins on retinal oxidative stress and inflammation in diabetes through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling[J]. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 2016, 301: 1-6. DOI:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.11.001 |

| [22] |

Chen YF, Shibu MA, Fan MJ, et al. Purple rice anthocyanin extract protects cardiac function in STZ-induced diabetes rat hearts by inhibiting cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2016, 31: 98-105. DOI:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.12.020 |

| [23] |

Pascual-Teresa S. Molecular mechanisms involved in the cardiovascular and neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins[J]. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2014, 559(5): 68-74. |

| [24] |

Peixoto H, Roxo M, Krstin S, et al. Anthocyanin-rich extract of Acai(Euterpe precatoria, Mart.)mediates neuroprotective activities in Caenorhabditis elegans[J]. J Functi Foods, 2016, 26: 385-393. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.012 |

| [25] |

Wang LJ, Li YM, Lei L, et al. Cranberry anthocyanin extract prolongs lifespan of fruit flies[J]. Experimental Gerontology, 2015, 69: 189-195. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2015.06.021 |

| [26] |

Wang L, Zhao Y, Zhou Q, et al. Characterization and hepatoprotective activity of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato(Ipomoea batatas, L. cultivar Eshu, No. 8)[J]. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 2016, 25(3): 607-618. |

| [27] |

Wang YW, Luan GX, Zhou W, et al. Subcritical water extraction, UPLC-Triple-TOF/MS analysis and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murr[J]. Food Chemistry, 2018, 249: 119-126. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.12.078 |

| [28] |

Zhao ZG, Yan HF, Zheng R, et al. Anthocyanins characterization and antioxidant activities of sugarcane(Saccharum officinarum L.)rind extracts[J]. Ind Crops Products, 2018, 113: 38-45. DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.01.015 |

| [29] |

Abdel-Aal ESM, Hucl P, Rabalskia I. Compositional and antioxidant properties of anthocyanin-rich products prepared from purple wheat[J]. Food Chemistry, 2018, 254: 13-19. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.170 |

| [30] |

Konczak-Islam I, Okuno S, Yoshimoto M, et al. Composition of phenolics and anthocyanins in a sweet potato cell suspension culture[J]. Biochem Eng J, 2003, 14(3): 155-161. DOI:10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00216-4 |

| [31] |

Konczak I, Terahara N, Yoshimoto M, et al. Regulating the quality of anthocyanins and phenolic acids in a sweetpotato cell culture towards production of polyphenolic complex with enhanced physiological activity[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2005, 16(9): 377-388. |

| [32] |

Moris F, Gotor V. A useful and versatile procedure for the acylation of nucleosides through an enzymic reaction[J]. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1993, 58(3): 653-660. DOI:10.1021/jo00055a018 |

| [33] |

Zaks A, Klibanov AM. Enzymatic catalysis in nonaqueous solvents[J]. J Biol Chem, 1988, 263(7): 3194-3201. |

| [34] |

Yan QL, Zhang LH, Zhang XF, et al. Stabilization of grape skin anthocyanins by copigmentation with enzymatically modified isoquercitrin(EMIQ)as a copigment[J]. Food Research International, 2013, 50(2): 603-609. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2011.04.007 |

| [35] |

Yan Z, Li CY, Zhang LX, et al. Enzymatic acylation of anthocyanin isolated from black rice with methyl aromatic acid ester as donor:Stability of the acylated derivatives[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2016, 64(5): 1137-1143. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05031 |

| [36] |

Narancic T, Davis R, Nikodinovic-Runic J, et al. Recent developments in biocatalysis beyond the laboratory[J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2015, 37(5): 943-954. DOI:10.1007/s10529-014-1762-4 |

| [37] |

Wachtmeister J, Rother D. Recent advances in whole cell biocatalysis techniques bridging from investigative to industrial scale[J]. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2016, 42: 169-177. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2016.05.005 |

| [38] |

Yang MY, Wu H, Lian Y, et al. Using ionic liquids in whole-cell biocatalysis for the nucleoside acylation[J]. Microbial Cell Factories, 2014, 13: 143. DOI:10.1186/s12934-014-0143-y |

| [39] |

宋静.提高蓝靛果花色苷稳定性菌种的筛选及作用条件研究[D].哈尔滨: 东北林业大学, 2011. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10225-1011146503.htm

|

| [40] |

Cheng JR, Liu XM, Chen ZY, et al. Mulberry anthocyanin biotransformation by intestinal probiotics[J]. Food Chemistry, 2016, 213: 721-727. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.032 |

| [41] |

Liang LH, Wu XY, Zhao T, et al. In vitro bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins from mulberry(Morus atropurpurea Roxb.)following simulated gastro-intestinal digestion[J]. Food Res Int, 2012, 46(1): 76-82. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2011.11.024 |

| [42] |

Forester SC, Waterhouse AL. Identification of cabernet sauvignon anthocyanin gut microflora metabolites[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56(19): 9299-9304. DOI:10.1021/jf801309n |

| [43] |

Chen Y, Li Q, Zhao T, et al. Biotransformation and metabolism of three mulberry anthocyanin monomers by rat gut microflora[J]. Food Chemistry, 2017, 237: 887-894. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.054 |

| [44] |

Jeon A, Suk K, Ji GE, et al. Assay of β-glucosidase activity of bifidobacteria and the hydrolysis of isoflavone glycosides by Bifidobacterium sp. Int-57 in soymilk fermentation[J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2002, 12(1): 8-13. |