对生物体基因进行改造是提高动植物遗传育种效率的有效方式。在基因改造的研究进程中,科研工作者对生物体中基因的修饰和改造研究不断开拓。1989年,Thomas等[1]利用同源重组(Homologous recombination,HR)技术实现小鼠的基因打靶;Urnov等[2]于2005年使用锌指核酶(zinc-finger nucleases,ZFNs)技术对T细胞基因组基因编辑;Nakajima等[3]于2010年使用转录激活样效应因子核酸酶(Transcription activator- like effector nucleases,TALENs)技术靶向切割双链DNA;2012年,随着成簇规律间隔短回文重复序列/成簇规律间隔短回文重复序列关联蛋白9(Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated proteins,CRISPR/Cas9)的发现至今,逐渐成为基因编辑研究中最为普遍的工具[4]。相比于HR,ZFN和TALEN技术基本实现基因的定点编辑,但是,这两种基因编辑技术需要组装识别切割区域DNA的结合蛋白体,相比于通过小向导RNA(Small guide RNA,sgRNA)与DNA碱基互补配对确定编辑靶向关系的CRISPR/Cas9核酸酶系统,难度和门槛要高得多[5]。

CRISPR/Cas9技术利用一段长度为20 nt左右的sgRNA引导Cas9核酸酶对目标DNA进行切割,引起DNA的修复进而改变目标DNA基序。碱基序列的排布是DNA信息含量丰富度的主要因素,然而基因组的表观修饰也提升了DNA的信息含量。包括被称为第5种碱基的5甲基胞嘧啶(5mC),被称为第6种碱基的5羟甲基胞嘧啶(5hmC),以及5甲酰胞嘧啶(5fC)和5羧基胞嘧啶(5caC)被更多地研究,为探索DNA的结构和功能提供有效的理论基础[6]。H3、H4组蛋白修饰通过调节染色质结构参与到基因的表达调控[7]。跨越过去20年的大量研究证据呈现了丰富的表观遗传机制,包括发现DNA修饰,组蛋白翻译后修饰(PTM)和非编码RNA(ncRNA)与表型相关的大量结果[8-10]。介导染色质结构组织与近2 m长的基因组DNA经过压缩、整合、组装成5 μm的三维结构体现了表观基因组的系统性和复杂性[11]。此外,异常染色质会引起很多人类疾病,而染色质状态和基因组的表观修饰又息息相关。例如,甲基化结合蛋白(Methyl CpG binding protein 2,MeCP2)的突变诱发招募去乙酰化酶类,导致Rett综合症[12];编码ATP水解酶亚基突变导致依赖ATP水解酶的染色质重塑因子功能障碍,引发神经退变、发育异常[13];基因组甲基化、乙酰化的变化与癌细胞的增殖分化相关[14];多能干细胞(Pluripotent stem cell,Ps)的潜能和定向分化受到基因组表观修饰的干预;在体细胞核移植过程中表观因子的重编程和基因的时序性表达相关[15]。利用改造后的CRISPR/Cas9系统对表观基因组进行研究,从而探讨基因组修饰作用,深入了解特定基因位置区域表观修饰的功能。

1 CRISPR/Cas9系统编辑表观基因组的技术基础CRISPR/Cas9是一种来自微生物免疫系统的可编程核酸酶[16]。当原型间隔区相邻基序(PAM)以及与其互补的目标DNA链的sgRNA同时存在时,sgRNA引导Cas9在靶DNA序列上产生位点特异性双链断裂(Double-strand breaks,DSBs),诱导DNA进行修复,如非同源末端连接(Nonhomologous end joining,NHEJ)或同源定向修复(Homologous directed repair,HDR)。通常情况下,HDR需要一个同源模板,对细胞周期的状态有特殊要求,因而产生NHEJ的概率会更大[17]。

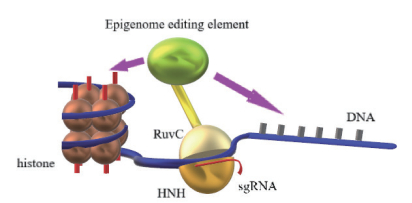

在CRISPR/Cas9进入目标DNA后打开双链,野生型Cas9(wt-Cas9)拥有的两个催化结构域HNH和RuvC分别对所处单链进行切割,产生DSBs[18]。通过灭活wt-Cas9的两个催化结构域的任意一个形成切割酶Cas9(Nicks Cas9,nCas9),在靶DNA序列上产生单链断裂而不是DSBs[19]。据报道,与产生DSB的wt-Cas9相比,使用nCas9切割目标DNA具有更低的脱靶率,可能是因为脱靶单个切口快速修复并因此检测不到[20-21]。如果将Cas9的两个催化结构域都失去活性,就变成催化失效的Cas9(Dead Cas9,dCas9),应用dCas9便可以和表观遗传修饰物的融合体共同作用基因组,可以实现改造基因组修饰的目的(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 CRISPR/Cas技术改造基因组表观修饰物 |

表观遗传是指DNA序列不发生变化,但基因表达却发生了可遗传的改变[22]。序列中的CpG二核苷酸(CpG dinucleotide)中的5'C易产生甲基化、羟甲基化等修饰,大量的研究表明这些修饰和基因的表达相关联[23]。利用无切割效应的dCas9融合共价修饰组蛋白或化学修饰DNA的酶基因可以对靶序列进行相应的修饰。Vojta等[24]报道使用Gly4Ser接头将dCas和甲基转移酶3A(DNMT3A)连接质粒同靶向目的基因BACH2和IL6ST的sgRNA同转染HEK293细胞系,改变了两个基因启动子区域甲基化程度,基因的表达显著降低。FMR1基因5'UTR区CGG扩增突变的高甲基化引起FMR1基因沉默进而导致脆性X综合征(Fragile X syndrome,FXS)[25],Liu等[26]利用dCas9和Tet甲基胞嘧啶双加氧酶1基因(Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 1,Tet1)融合转染FX52 iPSCs细胞系[27],对FMR基因5'端靶向序列进行去甲基化,为FXS治疗奠定可靠基础。

3 CRISPR/Cas9系统对染色质的表观修饰真核生物体内DNA的活动都依附于染色质,染色质元素的包装状态影响基因的复制、转录等功能。利用CRISPR/Cas9技术可以改变染色质重塑因子结合位点,从而调控转录。Ishihara等[28]通过CRISPR/Cas9技术靶向染色质绝缘子结合位点,消除HOXA基因启动子区与增强子区域之间的绝缘效应。在基因转录过程中,组蛋白的包装形式直接或间接地影响到基因染色质开放情况,从而调控转录因子与启动子或增强子的结合程度。利用CRISPR/Cas9可以改变染色质重塑因子与基因组的结合状态来影响染色质的结构。同样地,基于以非常精确的方式分配染色质修饰剂可以使用CRISPR/dCas9系统对组蛋白进行共价修饰[29],如组蛋白去甲基化酶(HDM)、组蛋白甲基转移酶(HMT)、组蛋白乙酰转移酶(HAT)、组蛋白去乙基化酶(HDAC)、组蛋白泛素连接酶(HUbq)。染色质修饰物的效应结构域将肽接头和核定位信号(NLS)与dCas9蛋白结合,提高染色质修饰的精确度和效率[30]。此外CRISPR/Cas系统提供了同时诱导几种靶向染色质修饰的可能性,因为sgRNA分子可以用作支架以招募与各种效应结构域连接的不同RNA结合蛋白,利用系统的正交性可以靶向多个基因座,使用来自不同物种的Cas9核酸酶及其相应的gRNA[31]。

4 CRISPR/Cas9系统对非编码RNA(Non-coding RNA,ncRNA)的调控广义的表观遗传的元素不单指DNA、组蛋白的化学或共价修饰,还包括ncRNA等元素。ncRNA在真核生物基因表达中起到至关重要的作用,例如,小分子RNA(microRNAs,miRNA)在基因转录后对mRNA进行调节,Danielson[32]和Zhang等[33]利用CRISPR/Cas9敲除miRNA簇引起因器官缺陷导致的胚胎致死;而长链非编码RNA(Longnon-codingRNA,lncRNA)既参与转录层次的调节,也参与转录后层次的调节。因为缺乏开放阅读框,敲除非编码基因的最主要的挑战是由标准CRISPR/Cas系统产生的小的缺失或插入可能不一定导致给定非编码基因的功能丧失[34]。

Jiang等[35]于2014年报道靶向HeLa细胞中人miRNA-93基因的5'区域在包含Drosha加工位点和种子序列的目标区域诱导几个小的插入缺失。参照智人miRNA数据库(miRBase;http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq1027)发现,即使高特异性敲除目标miRNA,也可能影响miRNA簇中其它miRNA的表达。在进化过程中,miRNA家族由共有相同5'种子区域[36],要做到不影响其他同源miRNA的表达的情况下敲除靶向miRNA是困难的[37]。为了克服这一挑战,通常允许标记基因通过同源重组(HR)整合到基因组中的选择系统。另外,构建双向引导载体sgRNA在靶向位点同时切割产生大片段删除。利用这些方法,成功地在各种人类细胞系中产生miR-21,miR-29a,UCA1,lncRNA-21A和AK023948的敲除[38-40]。这些结果证明CRISPR/Cas9系统在人细胞系中敲除ncRNA的可行性。

5 展望尽管以前表观遗传学领域侧重于分析不同细胞类型中的表观遗传状态以阐明生物学功能,但是对表观基因组编辑可能会彻底改变表观遗传学研究领域。使用dCas9连同具体的修饰因子共转染到活细胞可以实现目的基因的修饰以及染色质的修饰改造,更直接地从细胞层面了解其特定功能、从基因层面了解其特定区域修饰的具体作用。利用CRISPR/Cas9系统可以针对表观修饰异常的基因组进行“纠错”,也可以直接靶向产生突变的与染色质重塑相关因子恢复其功能,起到“御防”表观基因组疾病的作用。此外,在进行碱基序列的编辑时,为符合生物安全要求,通常进行内源性基因的改造,然而对于表观基因组的修饰并没有特定物种的具体安全规范。表观遗传元素通常与基因的表达相关联,部分增强子的表观修饰对基因表达程度存在显著的相关,基因组同一位置序列可能在基因表达中扮演不同的角色,使用CRISPR/Cas9对特定物种、特定组织、特定基因区域表观因子的改造适于探索表观因子和基因表达的因果关系,以及染色质区域结构的具体功能。此外,RNA的突变和修饰影响着动植物的生命活动,CRISPR/Cas9技术对RNA突变和修饰方面的研究将成为一种新的研究方向,便于探索获得性遗传、蛋白的翻译调控以及RNA的病毒检测,为探索基因功能、生命科学研究以及医疗疾病的研究奠定基础。

| [1] |

Thompson S, Clarke AR, Pow AM, et al. Germ line transmission and expression of a corrected HPRT gene produced by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells[J]. Cell, 1989, 56(2): 313-321. DOI:10.1016/0092-8674(89)90905-7 |

| [2] |

Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, et al. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases[J]. Nature, 2005, 435(7042): 646-651. DOI:10.1038/nature03556 |

| [3] |

Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Development of a new approach for targeted gene editing in primordial germ cells using TALENs in Xenopus[J]. Biol Open, 2015, 4(3): 259-266. DOI:10.1242/bio.201410926 |

| [4] |

Shipman SL, Nivala J, Macklis JD, et al. CRISPR-Cas encoding of a digital movie into the genomes of a population of living bacteria[J]. Nature, 2017, 547(7663): 345-349. DOI:10.1038/nature23017 |

| [5] |

周阳, 袁少飞, 蒋廷亚, 等. 基因组靶向修饰技术研究进展[J]. 生物学杂志, 2015, 32(5): 70-75. |

| [6] |

Sayeed SK, Zhao J, Sathyanarayana BK, et al. C/EBPβ(CEBPB)protein binding to the C/EBP|CRE DNA 8-mer TTGC|GTCA is inhibited by 5hmC and enhanced by 5mC, 5fC, and 5caC in the CG dinucleotide[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2015, 1849(6): 583-589. DOI:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.03.002 |

| [7] |

Salzler HR, Tatomer DC, Malek PY, et al. A sequence in the Drosophila H3-H4 promoter triggers histone locus body assembly and biosynthesis of replication-coupled histone mRNAs[J]. Dev Cell, 2013, 24(6): 623-634. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.02.014 |

| [8] |

Szulwach KE, Jin P. Integrating DNA methylation dynamics into a framework for understanding epigenetic codes[J]. Bioessays, 2014, 36(1): 107-117. DOI:10.1002/bies.v36.1 |

| [9] |

Zhang C, Gao S, Molascon AJ, et al. Bioinformatic and proteomic analysis of bulk histones reveals PTM crosstalk and chromatin features[J]. J Proteome Res, 2014, 13(7): 3330-3337. DOI:10.1021/pr5001829 |

| [10] |

Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Eissmann M, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2013, 73(3): 1180-1189. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850 |

| [11] |

Young IT, Verbeek PW, Mayall BH. Characterization of chromatin distribution in cell nuclei[J]. Cytometry, 1986, 7(5): 467-474. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0320 |

| [12] |

Liyanage VR, Rastegar M. Rett syndrome and MeCP2[J]. Neuromolecular Med, 2014, 16(2): 231-264. DOI:10.1007/s12017-014-8295-9 |

| [13] |

Friez MJ, Brooks SS, Stevenson RE, et al. HUWE1 mutations in Juberg-Marsidi and Brooks syndromes: the results of an X-chromosome exome sequencing study[J]. BMJ Open, 2016, 6(4): e009537. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009537 |

| [14] |

庄涵虚, 马旭东, 赖亚栋, 等. RNA干扰沉默HDAC1基因对胃癌细胞增殖、凋亡、组蛋白乙酰化和甲基化的影响[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2014, 34(2): 246-250. |

| [15] |

Matoba S, Liu Y, Lu F, et al. Embryonic development following somatic cell nuclear transfer impeded by persisting histone methylation[J]. Cell, 2014, 159(4): 884-895. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.055 |

| [16] |

Ma Y, Zhang L, Huang X. Genome modification by CRISPR/Cas9[J]. FEBS J, 2014, 281(23): 5186-5193. DOI:10.1111/febs.2014.281.issue-23 |

| [17] |

Miyaoka Y, Berman JR, Cooper SB, et al. Systematic quantification of HDR and NHEJ reveals effects of locus, nuclease, and cell type on genome-editing[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 23549. DOI:10.1038/srep23549 |

| [18] |

Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity[J]. Science, 2012, 337(6096): 816-821. DOI:10.1126/science.1225829 |

| [19] |

Renouf B, Piganeau M, Ghezraoui H, et al. Creating cancer translocations in human cells using Cas9 DSBs and nCas9 paired nicks[J]. Methods Enzymol, 2014, 546: 251-271. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-801185-0.00012-X |

| [20] |

Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity[J]. Cell, 2013, 154: 1380-1389. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 |

| [21] |

Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, et al. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins[J]. Genome Res, 2014, 24: 1012-1019. DOI:10.1101/gr.171322.113 |

| [22] |

Stefanska B, MacEwan DJ. Epigenetics and pharmacology[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2015, 172(11): 2701-2704. DOI:10.1111/bph.13136 |

| [23] |

Xu Y, Wu F, Tan L, et al. Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells[J]. Mol Cell, 2011, 42(4): 451-464. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.005 |

| [24] |

Vojta A, Dobrinić P, Tadić V, et al. Repurposing the CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted DNA methylation[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2016, 44(12): 5615-5628. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkw159 |

| [25] |

de Esch CE, Ghazvini M, Loos F, et al. Epigenetic characterization of the FMR1 promoter in induced pluripotent stem cells from human fibroblasts carrying an unmethylated full mutation[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2014, 3(4): 548-555. DOI:10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.07.013 |

| [26] |

Liu XS, Wu H, Krzisch M, et al. Rescue of Fragile X Syndrome Neurons by DNA Methylation Editing of the FMR1 Gene[J]. Cell, 2018, 172(5): 979-992. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.012 |

| [27] |

Urbach A, Bar-Nur O, Daley GQ, et al. Differential modeling of fragile X syndrome by human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2010, 6: 407-411. DOI:10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.005 |

| [28] |

Ishihara K, Nakamoto M, Nakao M. DNA methylation-independent removable insulator controls chromatin remodeling at the HOXA locus via retinoic acid signaling[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2016, 5(24): 5383-5394. |

| [29] |

Rots MG, Jeltsch A. Editing the epigenome: overview, open questions, and directions of future development[J]. Methods Mol Biol, 2018, 1767: 3-18. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-7774-1 |

| [30] |

Chen, B, Gilbert, LA, Cimini, BA, et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell[J]. 2013, 155: 1479-1491. http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/24360272

|

| [31] |

Puchta H. Using CRISPR/Cas in three dimensions: towards synthetic plant genomes, transcriptomes and epigenomes[J]. Plant J, 2016, 87(1): 5-15. DOI:10.1111/tpj.2016.87.issue-1 |

| [32] |

Danielson LS, Park DS, Rotllan N, et al. Cardiovascular dysregula-tion of miR-17-92 causes a lethal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenesis[J]. FASEB J, 2013, 27(4): 1460-1467. DOI:10.1096/fj.12-221994 |

| [33] |

Zhang Z, Ursin R, Mahapatra S, et al. CRISPR/CAS9 ablation of individual miRNAs from a miRNA family reveals their individual efficacies for regulating cardiac differentiation[J]. Mech Dev, 2018, 150: 10-20. DOI:10.1016/j.mod.2018.02.002 |

| [34] |

Basak J, Nithin C. Targeting non-coding RNAs in plants with the CRISPR-Cas technology is a challenge yet worth accepting[J]. Front Plant Sci, 2015, 6: 1001. |

| [35] |

Jiang Q, Meng X, Meng L, et al. Small indels induced by CRISPR/Cas9 in the 5' region of microRNA lead to its depletion and Drosha processing retardance[J]. RNA Biol, 2014, 11(10): 1243-1249. DOI:10.1080/15476286.2014.996067 |

| [36] |

Cipolla GA. A non-canonical landscape of the microRNA system[J]. Front Genet, 2014, 5: 337. |

| [37] |

Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9[J]. Science, 2014, 346(6213): 1258096. DOI:10.1126/science.1258096 |

| [38] |

Huo W, Zhao G, Yin J, et al. Lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 vector mediated miR-21 gene editing inhibits the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer cells[J]. J Cancer, 2017, 8(1): 57-64. DOI:10.7150/jca.16723 |

| [39] |

Ho TT, Zhou N, Huang J, et al. Targeting non-coding RNAs with the CRISPR/Cas9 system in human cell lines[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2015, 43(3): e17. DOI:10.1093/nar/gku1198 |

| [40] |

Zhen S, Hua L, Liu YH, et al. Inhibition of long non-coding RNA UCA1 by CRISPR/Cas9 attenuated malignant phenotypes of bladder cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(6): 9634-9646. |